From the New Yugoslav Man to “Humanitas Heroica”: Eugenics, Culture and the Paradox of Modernity in Inter-War Yugoslavia In this paper, I would like to examine the contradictions of the eugenic movement in Yugoslavia. I will argue that the broad eugenic and racial movement in inter-war Yugoslavia was guided by a form of “liberal” eugenics which sought to create a new Yugoslav person as a synthesis of the racial and cultural attributes of the three Yugoslav tribes and the assimilation through inter-marriage of non-national minorities. Under the influence of the guiding ideologies of the era, including Fascism and Nazism, a darker side to Yugoslav eugenics emerged: however it remained rooted in liberal modern Yugoslav concerns. Ironically, it was from among Serbian intellectuals on the nationalist right that ideas emerged which, despite their rejection of social Darwinism, were closest to Fascist and Nazi ideology. That their anti-Western and anti-European rhetoric had originated in avant-garde left-wing circles and that their advocacy of a Balkan superman had originated in the scientific theories of Yugoslav eugenicists was simply one of the many paradoxes of modernity in Yugoslavia in the inter-war period. 1

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

From the New Yugoslav Man to “Humanitas Heroica”: Eugenics,

Culture and the Paradox of Modernity in Inter-War Yugoslavia

In this paper, I would like to examine the contradictions of

the eugenic movement in Yugoslavia. I will argue that the

broad eugenic and racial movement in inter-war Yugoslavia was

guided by a form of “liberal” eugenics which sought to create

a new Yugoslav person as a synthesis of the racial and

cultural attributes of the three Yugoslav tribes and the

assimilation through inter-marriage of non-national

minorities. Under the influence of the guiding ideologies of

the era, including Fascism and Nazism, a darker side to

Yugoslav eugenics emerged: however it remained rooted in

liberal modern Yugoslav concerns. Ironically, it was from

among Serbian intellectuals on the nationalist right that

ideas emerged which, despite their rejection of social

Darwinism, were closest to Fascist and Nazi ideology. That

their anti-Western and anti-European rhetoric had originated

in avant-garde left-wing circles and that their advocacy of a

Balkan superman had originated in the scientific theories of

Yugoslav eugenicists was simply one of the many paradoxes of

modernity in Yugoslavia in the inter-war period.

1

From its inception, the Yugoslav idea was steeped in the

language of revolution and eugenics. In the current

intellectual climate, the term “eugenics” has a highly

negative association, invariably reduced to the worst case

scenario: Josef Mengele on the Nazi payroll. However, early

Yugoslav eugenics even at its hubristic and dystopian worst

simply was not like this: it didn’t aim at the eradication of

alien nations; rather it sought a synthesis of the existing

nations which would result in a new race transcending the

racial, national and cultural divisions of the past.

Early Yugoslav ideologists believed that the mixing and cross

breeding of the races would be enough to achieve a Yugoslav

nation and consciousness. J. Žubović, writing in 1924, argued

that a new Yugoslav person was being created who would be the

progenitor of the new state. By bringing closer the unity and

synthesis of the tribal elements through cross breeding, a

Yugoslav person exemplifying the best qualities of the race

would be created. As well as suggesting that members of the

different tribal groups be sent to locations where other

tribal groups were in the majority in order to encourage cross

breeding, Žubović advocated the reform of family law to

encourage mixed marriages. Civil marriages, he wrote, must

2

tear down the religious barriers which stood in the way of

equality and national eugenics would have to regulate the

rites of marriage instead of priests. For their part, he

believed that those minorities which were not part of the

Yugoslav nation could be peacefully culturally assimilated.

Not all Yugoslavs believed that the making of a Yugoslav

nation would be that simple. The writer Milan Pribičević, for

example, argued that a racially-unified Yugoslav state would

only be achieved with the appearance of a “modern, great,

cultured, and social Yugoslavia” in which there would be a

“progressive peasantry with clean respectable homes and

villages, well fed and highly literate; the organisation of

working class life in modern and healthy towns; a strong rail

network, big factories and our own industries; on the sea, our

great ships which sail in all directions; a Yugoslav woman

elevated to the standards of modern times and law; a highly

educated people, strong science and art; the acculturation,

prosperity and satisfaction of all the needs of every

citizen”.

Government experts were also concerned about social conditions

in the town and the village. In 1927 the Ministry of Health

3

official, Vladimir S. Stanojević warned that the health

situation in the countryside was worrying and in both the town

and the village the ordinary people were not educated in the

essentials of hygiene. As a result, diseases such as malaria,

typhus and tuberculosis were rife. His recommendations were

similar to those of Pribičević: universal social security, a

safe clean environment in which to work, modern apartments and

housing and worker and peasant co-operatives where groceries,

hygienic food and clothes could be purchased. Stanojević was

speaking from the position of someone who was passionately in

favour of eugenic solutions to the problems of Yugoslav

society. As early as 1920, he had written a book on the

virtues of eugenics for the Ministry of National Health. In

the book he compared eugenics to the breeding of livestock,

yet in his conceptualisation, eugenics was completely divorced

from the notion of eugenics as it was envisaged in Germany and

many other European countries. Although he called for it to be

the religion of the future and envisaged the day when eugenics

would be the basis for all marriages, he also called for an

end to militarism and the “tearing of young people” from their

homes to “die in dirty and unhealthy barracks”. Similarly,

while he lauded the racial breeding of the English and

Americans which had enabled them to rule over whole dominions,

4

he believed that the strength of these races was attributable

to the mixing of different cultured and primitive races. In

the United States of America, for example, Spanish immigrants

had inter-bred with native tribes and this had improved the

quality of the American race. The implications for Yugoslavia

did not need to be spelt out.

However, there was a darker side to Stanojević’s book. While

lauding the mixed racial make up of the American nation he

also drew admiring attention to the eugenic laws in the

United States which advocated the sterilisation of the

incapable and the weak and the prohibition of marriages

between Americans and those deemed to be criminal, alcoholic,

epileptic, those with learning difficulties, or who were

mentally ill or handicapped. He also noted with a certain sang

froid similar policies in Germany. These sentiments were not

isolated ones. In an article of 1935, for instance, the

president of the Yugoslav Doctors’ Society, Svetislav

Stefanović, stated that while he opposed abortion and

artificial means of controlling the number of children on

social grounds, sterilisation was necessary in cases where the

health of the race was at risk. In order to fight against

abortion and its culture of secrecy, laws would have to be

5

introduced for racial, spiritual and medical hygiene. Such a

policy, he asserted, would also save money. In Germany, the

cost of the births of the feeble minded, the blind, the lame,

alcoholic and psychopaths amounted to the equivalent of

millions of dinars each year. Yet as harsh as these proposals

appear to be, Stefanović’s ideas also contained a strong

socially-progressive agenda as far as they mostly addressed

the problems of life for women in the villages. Insofar as the

article broached the subject of forced sterilisation it also

advocated improvements in medical facilities for women in the

villages and better education for them. Moreover, these

recommendations paled into insignificance with those of the

Director of the Central Institute for Hygiene Dr Stevan Ivanić

who declared that Nazi sterilisation laws were a model of how

to address racial hygiene problems. Defining racial hygiene as

the selection, segregation and sterilisation of the weaker

races and types in favour of “racially stronger types”, he

called for the “removing from the racial community of the

genetically burdened (the insane, cretins, the dumb, the

blind, genetically criminal, alcoholics, tramps and so on”

through sterilisation and segregation.

6

The theme of improved social care in the villages dominated

the proceedings of the sixteenth congress of the Yugoslav

Doctors’ Society (JLD) in September 1934. In his keynote

speech to the congress, Stefanović complained that although

the village was recognised as the foundation of all national

culture, “it hardly ever saw the benefits and tastes of

culture” and instead was abandoned and allowed to sink into

ignorance and poverty. In particular, in the villages

facilities for pregnant women were completely inadequate and

this contrasted negatively with the situation in Italy and

Soviet Russia where the rate of child mortality was much

lower. If the medical standards of the city were transferred

to the village, this would have the effect of bringing the

village into closer contact with the city and would make

peasants less suspicious of the city, he argued. As solutions

to the hygiene problems of the village, he recommended the

construction of miniature hospitals, dispensaries for pregnant

women and those suffering from tuberculosis, a doctor for

every village, and the creation in the Ministry for National

Health of a special office for the health of the villages

similar to the institutions which existed in Italy and Soviet

Russia with a special section devoted to the defence and

protection of the mother and the child. He also recommended

7

that all those training to be doctors should have to spend at

least two years of their training working in the villages,

that the health of the villages be a compulsory module in

medical schools and that a tax be introduced to fund this

programme. In order to measure the level of cultural life in

the villages, Stefanović suggested that hundreds of thousands

rather than “barely one” villager should know the works of

Shakespeare and Goethe.

The JLD congress of 1934 heard proposals from a number of

other leading medical practitioners in Yugoslavia, many of

which were connected to the themes of abortion, birth control

and the general health of the village. Speaker after speaker

lined up to highlight the deplorable living and moral

standards of life in the village: the poverty, the lack of

hygiene, the insufficient medical facilities, the primitive

beliefs, the illnesses and the alcoholism. Yet the longest

papers were given over to the subject of birth control and

sterilisation. Dr. M. Zelić, for one, addressed the issue of

the low birth rate in the country and the role which

contraception was playing in the prevention of a high birth

rate. Placing the “crisis of natality” in the context of the

social and economic crises of the 1930s he praised the

8

policies of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy for the way in

which they had been able to increase the number of births in

their states. Yet his recommendations reflected both the

mindset of enlightened liberal modernism and a fascination

with the politics and policies of Fascism. On the one hand, in

order to increase the number of births, he called for such

punitive measures as taxes on bachelors and affluent women who

“for whatever reason” chose not to bear children. In the case

that such women were not able to have children, they would be

asked to assist poor rural families in the upbringing of their

children. Like other speakers he also called for the

establishment of an institute modelled on similar institutes

in Italy and Germany within the National Ministry of Health

which would be devoted to the health and defence of the mother

and the child. At the same time, however, many of the policies

he advocated demonstrated the liberal face of Yugoslav

eugenics. For example, instead of campaigns against the

legalisation of abortion which he argued were self defeating

and doomed to failure, he called for more social protection

for the vulnerable, especially the unemployed and the poor and

thus remove the primary motivation for abortions. To defeat

unemployment and poverty it was not necessary to restrict the

numbers of births but to achieve social justice. Without

9

this, poor women would continue to fill the statistics of

women who had had deadly backstreet abortions. Zelić also

called for the recognition by law of those children who had

been born out of wedlock:

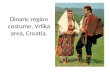

In the travel writing of foreigners who ventured to Yugoslavia

in the inter-war period, much was made of the physical

superiority of the Yugoslavs and the writing of many Yugoslav

ethnographers betrayed the belief that there was something

intrinsically superior about the physiognomy of the Yugoslav

man. With the creation of the Yugoslav state in 1918, there

was an upsurge in interest in racial anthropology and science.

Scientists took field trips to study populations in the most

remote regions of the new state to discover the secrets of the

Yugoslav race. However, most ethnographers and anthropologists

agreed that the prototype of the new Yugoslav man was to be

found among the Dinaric people in the Dinara Mountains.

Already in 1921 Jovan Cvjić declared that the Dinaric man was

“young, full blooded and keenly alive to natural phenomena”

with a “lively temperament” and “a consuming passion and a

violence which reaches a white heat”. In his monumental study

of the ethnography of the Yugoslavs, published in 1939,

Vladimir Dvornikovic likewise eulogised the qualities of the

10

Dinaric race, in particular their physical prowess, their

tenderness and at the same time their warrior-like attitude

towards life. Possibly, the most prolific propagator of the

qualities of the Dinaric race was the anthropologist Dr.

Branimir Maleš who devoted countless articles and books to the

subject. Through his various field trips, he became convinced

that the Dinaric people were a superior race characterised by

large heads, long faces, brachcephalic-shaped skulls and

unusual stature. Although the Dinaric race was ethnologically

comparable to the Nordic race, he stressed that the Dinaric

race was unique. Maleš’ research was amazingly extensive and

in his trips to remote Dinaric villages he studied the

menstruation patterns of girls and the diets and work patterns

of communities. He measured nose sizes, head shapes, examined

frontal and temporal lobes, the colour of hair, the complexion

of faces and the colour of eyes as well as height and build.

He claimed to have discovered at least two different types of

Dinarics – dark and blonde Dinarics - and believed that the

latter proved the similarity between the Dinaric and the

Nordic races. As a researcher with an extensive interest in

the racial make up of the Dinaric race, Maleš made much of the

superior qualities of the Dinaric man, “whom even the most

chauvinistic German scientists admire, whose character, both

11

physical and spiritual, they rank in the same order as the

character of the Nordic German race”. For Maleš, there was no

doubt that “the Dinaric race is superior, dominant in its

biological qualities, in its qualities of adaptability and in

its easy acceptance of death” in short, a “chosen people in

the defence of Christian Europe”.

The idea that the Dinaric race represented something racially

superior was championed by many anthropologists and writers.

Dvorniković, for example, in a little-read study of 1930

poured scorn on what he termed the Yugoslav “snobs” who wanted

to imitate the practices and traditions of Western Europe. He

declared that Yugoslavs should be proud of their Balkan

origins and should resist aping the West where inhumane

capitalism predominated. On the contrary, the Slavic psychic

mentality could represent salvation for the West since the

racial character of the Dinaric man was not only steeped in

heroism but was intellectually sharp, betraying a human soul

which was deeply disposed towards culture. He noted that it

was from the patriarchal Dinaric man that the greatest epic

poetry had emerged. According to Dvorniković, this

“revolutionary dynamism” and “fanaticism” had often been

wrongly interpreted by Western observers. Other scientists and

12

anthropologists who represented liberal Yugoslavism also

shared some of Dvornikovic’s outlook. Svetislav Stefanović

writing in 1935 went as far as to contend that many of the

cultural and literary geniuses through history had been part

Dinaric at least, including Goethe, Beethoven and Hegel. Race

was the “primary, founding and constructive factor” in the

building of a state and culture and the young Yugoslav

nationalism had been made strong with the presence of a racial

element. Comparing favourably the mixing of Nordic and Dinaric

races with the negative effects of the mixing between superior

and degenerate races, he denied that there was an element of

racism or discrimination in the study of eugenics and stated

his belief that the use of racism should be prevented.

Although both Maleš and Stefanović rejected the idea that the

Nordic racial type represented a master race, this does not

mean that they did not subscribe to the concept of a master

race, just that they did not require the Aryan theory of

racial superiority. To the Aryan übermensch they opposed the

idea of the Dinaric superman. According to Stefanović the era

of the Aryan übermensch was over and the hour of the Dinaric

superman had dawned, a superman imbued not just with racially-

superior qualities but also a sharper instinct for social

13

justice and the rights of the community. “Perhaps this human

racial type has completed his historical mission – like his

individualistic capitalism has,” he wrote, “and the time has

arrived for the entrance of another man of the Dinaric racial

type who […] by the characteristics of his soul and his

spirit, heralds the arrival of a new person emblematic of a

new social and cultural structure of society and the state”.

The Dinaric human type of man would be “an heroic human type

of man; not a hero of commerce - hard, cruel, brutal, egoistic

and inhumane - but a hero of complete kindness, of a warm

heart and soul, who not only rules with his intellect but also

heroically bears the slings and arrows of fate which the

ruling type devoted to a hedonistic understanding of life

cannot imagine and for which concept it seems to me G. Gezeman

discovered a very fortunate and very characteristic adjectival

expression – humanitas heroica. If I had to choose between the

Nordic type of rational man and the Dinaric humane type, I

would opt for the latter. We should obey not just the wishes

of the individual, but also the dictates of history.”

The concept of Slavic messianism with a Balkan humanitas heroica

saving the West from its own decline was an idea first

explored in the writings of Russian novelists of the

14

nineteenth century such as Fedor Dostoevsky and later revived

in the early twentieth century by Oswald Spengler. This notion

also provided fertile material for avant garde writers and

artists in 1920s Yugoslavia looking to the East for

inspiration. Although invariably left-wing, opposed to

militarism and admirers of the Russian Revolution, they

nonetheless rejected what they perceived as the tediously

respectable, rationalistic and bourgeois values of the West.

The Zenithist Movement of Boško Tokin and Ljubomir Mičić, in

particular, avidly propagated the idea that with the creation

of the Yugoslav state a new Balkan race had been created.

Anarchic, iconoclastic and irreverent, the Zenithists

delighted in mocking and savaging the cherished western

aspirations of more mainstream artists and writers. Writing in

1921, for instance, Mičić declared that “the beginning of the

great century is characterised by the fiercest battle between

the East and the West: a duel of cultures. The position of the

Zenithists is to be against western culture”.

At the heart of the Zenithist manifesto was the new Balkan man

– the Barbarogenius. According to Mičić, the Barbarogenius was

“the supreme spirit”. The Zenithists imagined the

Barbarogenius as an allegorical and metaphorical figure on a

15

messianic mission to save and protect Yugoslavia against the

West “whose rotten ideas could not be allowed to spread in the

Balkans and the East”. On the contrary, the salvation of the

West lay in its allowing the spreading of raw primitive energy

from the Balkans which would revive the world. The anti-

western stance of the Zenithists can be seen most clearly in

the Zenithist manifesto of 1921 which pours scorn on the

bourgeoisie. In the manifesto, Mičić propagated the idea of

the naked Barbarogenius flying above the globe while below the

lives of the affluent are shattered: “Bolt your doors West –

North - Central Europe – The Barbarians are coming! Bolt them,

but we shall enter! We are the children of arson and fire – we

carry man’s soul. We are the children of the South East

Barbarogenius” who have “hoisted high their visionary flag of

redemption and sing the Eastern Slavic song of Resurrection”.

This anti-western view point of was also shared by the

literary right who saw in the rationalism and democracy of the

West the negation of the best traditions of the Slavic world

and also a number of traits – such as urbanism and modernity –

which they felt had a dehumanising effect on the peasant

society of Yugoslavia. There thus developed a discourse which

was both anti-Western in the sense of opposing urban ideas of

16

modernity and also anti-European insofar as some writers

argued that the Serbs were not a European nation. Despite

superficial similarities between these rightist intellectuals

and Yugoslav some eugenicists and racial theorists insofar as

they had a common belief in the Yugoslav man to regenerate

Europe, ultimately they were diametrically opposed. While

right-wing intellectuals lauded the purity of the village,

eugenicists aimed to use the values of urban modernism to

elevate life in the villages. Moreover, while eugenicists and

racial anthropologists embraced race science as one way out of

the Yugoslav national question, these rightist intellectuals

denounced it as a symptom of a godless and rationalistic

society while at the same time appropriating much of its

rhetoric. In the eyes of the literary right in Yugoslavia in

the 1930s, the city was the centre of all social and medical

illness and they looked to a mythical past when such

phenomenon had not existed. Anti-Semitism also played an

integral part. For them, the rational atheistic modern society

represented the victory of a pernicious Jewish influence which

had also been the guiding spirit, they argued, behind the

French revolution of 1789 and the Russian Revolution in 1918.

17

For these writers, many of the worst features of modern urban

life had emerged from the West; they justified the return to

the village, Slavdom and God as an escape from the influence

of a soulless West dominated by the big city mentality with

its “trashy” culture. In an article written in July 1929 the

novelist Vladimir Vujić expressed the conflation between

hostility to the city and Europe clearly when he stated that

the Serbs were not part of Europe because their ideology had

developed differently to the rest of Europe. Like Velmar-

Janković, Vujić attacked the nihilistic capitalist and

rationalist culture of the West personified in the city. As he

argued in his most well known essay on the subject in 1931,

Yugoslavs should create their own autonomous culture, a

culture which would avoid the degenerate hypocrisy, sex and

lies of the West. “No,” he concluded, “we are not Europe and

it is good that we are not. We are not Europe and we are not

the West by our ethical understanding of the world, by our

spiritual style, by our view of the world and life. We are not

and it is good that we are not.” On the one hand, Vujić

believed that the decline of the West was attributable to its

adoption of a decadent culture which was destroying

civilisation. But more than this, western culture was simply

old and moribund, he argued. The West, he explained, had had

18

its youth in the Middle Ages. In the new era, Yugoslavism

represented a young vibrant spiritual phenomenon, a bridge to

the West and the East with the Slavs playing an important

messianic role in the regeneration of Europe. In a Europe

ruled through Masonic lodges, atheism and the arrogance of the

“liberated man” salvation could only be found in a return to

spirituality, Christianity and specifically Orthodoxy. The

Yugoslavs through their religion, “racial genius” and “racial

soul” could play a key role in the renaissance and

reinvigoration of a sick Europe.

The playwright Vladimir Velmar-Janković was also critical of

the urge to embrace the values of the West and Europe. In his

study of 1938 entitled The View from Kalmegadan he urged Serbs to

return to the persona of the revolutionary man of the 1804

uprising. According to Velmar-Janković the Serb was a man of

the East not a European; in short, he was a person of the

“Belgrade living orientation” to whom material greed was alien

(since this was an urban ideology connected with the Jewish

and gypsy districts of Belgrade). The Belgrade man was

represented in the nineteenth-century Serbian peasant who in

previous centuries had been the carrier of the strength of

Serbian society. In 1918, however, he had found himself

19

surrounded by Western influences and European civilisation. In

the days of Turkish rule, the Serbs had ironically been

protected from the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and

humanism. Instead, the Serbs had developed the peasant

zadruga, tribal loyalties and familial relationships. However,

following 1918, contemporary life weakened the spiritual

strength of the Serbs; Christianity had been pushed away and

the worst facets of life from Europe had been adopted. The

patriarchal heroic view of life conflicted with the

materialistic modern understanding of life: greed reigned

supreme and the very foundations of the nation were destroyed.

The writer blamed intellectuals who had “swallowed all that

carried the label ‘made in Europe’”. Like others on the

literary and political right, he negated the idea of the class

struggle. For him, the real difference existed between Serbia

and the more “western parts” of the Yugoslav state –

especially Slovenia and Croatia. He believed that Belgrade as

a synonym for Serbia and the Serbian man was possessed of the

mystical qualities “racial purity and steely blood”. As far as

Velmar-Jankovic was concerned, the Belgrade orientation had to

spiritually conquer all parts of the Yugoslav homeland. When

it had, the victory of eastern values in Croatia would

surmount the current “sick tendencies” of Europe.

20

In conclusion, eugenics is often reduced to the worst case

scenario. This was simply not the case in Yugoslavia. While

Yugoslav eugenicist and racial anthropologists certainly

wanted to create a Yugoslav race and improve the racial

quality of the nation, by and large they wanted to realise

this through inter-marriage rather than segregation or

extermination. Though they looked on with admiration at some

of the health and eugenics policies of Nazi Germany and

Fascist Italy, these policies were always adapted to the

special circumstances of a multi-national society. I submit

that modernism plus liberalism equalled Yugoslavism. By

contrast, it was those who were most hostile to science and

technology who demonstrated the greatest propensity to embrace

ideas which were most similar to those of Nazism and Fascism,

those impeccably western ideologies. In their hatred of the

cities as the root of all decadence, their diatribes against

Masonic and Jewish influence, their opposition to “degenerate”

contemporary life and their cult of the peasant and village

life, they far more closely mirrored the ideology of Nazism

and Fascism than their Yugoslav eugenic rivals ever did. In

opposing one form of modernist ideology as alien and dangerous

21

Related Documents