Landscapes of cult and kingship Roseanne Schot, Conor Newman & Edel Bhreathnach EDITORS FOUR COURTS PRESS

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Landscapes of cult andkingship

Roseanne Schot, Conor Newman & Edel Bhreathnach

EDITORS

FOUR COURTS PRESS

From cult centre to royal centre: monuments, mythsand other revelations at Uisneach

ROSEANNE SCHOT

Founded on a long and venerable history as a ceremonial centre, the royalpedigree of Uisneach could hardly be more illustrious. The sacred centre of Mide,‘the middle’ land, and ‘navel’ of Ireland (pl. 3), Uisneach (Old Irish Uisnech) wasappropriated as a symbolic, if not de facto, royal seat of the southern Uí Néill andits ruling dynasts styled ríg Uisnig, ‘kings of Uisnech’, in early medieval king-lists.1

The most prominent among them hailed from Clann Cholmáin, who, as theleading dynasty in the midlands and one of dominant ruling lineages of the UíNéill federation from c.AD728 to 1022, were also regular holders of the kingshipof Tara.2 Although Uisneach is less explicitly associated with kingship in the earlyliterature than places like Tara, Emain, Rathcroghan and Dún Ailinne, it isnevertheless closely linked with the four great ‘pre-Christian’ provincial capitalsby virtue of its identification as the umbilical centre of Ireland and meeting pointof the ancient provinces, and is also, like them, depicted as a place of assembly,burial and pagan ritual. In terms of its overall character and longevity as a focalcentre, as well as many of its physical and cultural attributes, Uisneach also sharesmuch in common with these and other multi-period ritual complexes thatemerged as centres of kingship during the later prehistoric and early medievalperiods.

While current research is beginning to question the suitability of the term‘prehistoric’ to describe those four centres identified as pre-Christian royal capitalsin early medieval sources, many of the traditional principals that underpin its useremain valid. Among them is the recognition that all have a protracted history ofritual and ceremonial use, often extending back to the Neolithic, and that the IronAge marks something of an apogee in their evolution as regional foci – aphenomenon believed by many to be closely linked with the evolving institutionof sacral kingship that we see such tantalizing glimpses of in the early literature.On these grounds alone (and others besides), centres like Tara, Emain,Rathcroghan and Dún Ailinne clearly differ fundamentally from early medievalroyal residences such as Lagore and Cró Inis; however, when it comes to

1 LL, i, pp 196–8 (42a–b); J. MacNeill (ed.), ‘Poems by Flann Mainistrech’ (1913), 82–92; A. MacShamhráin & P. Byrne, ‘Prosopography I’ (2005). See also, for example, F.J. Byrne, Irish kings (1973), p. 87;T.M. Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland (2000), p. 24. 2 For further details and discussion of thisdynasty, see A. Mac Shamhráin, ‘The emergence of Clann Cholmáin’ (2000); Byrne, Irish kings, especially

87

comparing them with other multi-period complexes with royal associations –places like Uisneach, Tailtiu, Knowth (Brú na Bóinne) and Cashel, to name but afew – the distinctions become increasingly complex and ill-defined.

A central issue in the debate concerns the actual role(s) of such places duringthe early medieval period. While activity during this period is indicated, forexample, at all four of the major royal centres, there has been a tendency to treatit as somehow peripheral to the main period of the sites’ use. This is perhapsunderstandable given the relatively ephemeral or otherwise uncorroborated natureof such evidence when contrasted, for instance, with the great ceremonialenclosures, temples and other ritual structures, and the prestigious, sometimesexotic, material that characterize the preceding Iron Age horizons at Emain, DúnAilinne and Tara.3 Moreover, the relative dearth of early historical, as distinct fromliterary, references to these places has fuelled a perception of them as essentiallyprehistoric entities and has contributed to the view that their significance duringthe early medieval period was primarily, if not exclusively, symbolic. Yet, contraryto this assumption – and the even more stark spectre of ‘desertion’ propagated intexts such as Félire Óengusso – recent analyses of both Tara and Rathcroghansuggest that their importance as centres of kingship not only drew on thesignificances invested in existing monuments, but in some cases also involved theirmodification and augmentation, as well as the construction of substantial newmonuments, into the early medieval period.4

Whereas material investment on a significant scale during the early medievalperiod has yet to be definitively proven for many of the royal complexes, theevidence from Uisneach is, in this respect, unequivocal. Indeed, the appropriationof the Hill of Uisneach as a royal seat of the southern Uí Néill appears to haveprompted a flurry of building activity, including the construction of two of themost impressive enclosures in the complex: a conjoined, bivallate ringfort on thesummit, in Rathnew townland (hereafter ‘Rathnew Enclosure’),5 and a largeenclosure defined by two widely spaced ramparts on the northern slope of the hill,in the townland of Togherstown (fig. 5.2). Reassessment of excavationsundertaken at Uisneach by R.A.S. Macalister and R.L. Praeger from 1925 to19306 suggests evidence of high-status occupation at both of these sites between

pp 87, 94, 282; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, especially pp 21–2, 501–2, 571–2; MacShamhráin & Byrne, ‘Prosopography I’. 3 See C. Newman, Tara (1997); H. Roche, ‘Excavations at Ráithna Ríg’ (2002); C. Lynn, Navan Fort (2003); E. Grogan, Rath of the Synods (2008); S. Johnston & B. Wailes(eds), Dún Ailinne (2008). 4 Newman, Tara, 77–88; idem, ‘Procession and symbolism at Tara’ (2007); J.Waddell, J. Fenwick & K. Barton, Rathcroghan (2009). 5 This enclosure is known locally as ‘The Palace’,presumably on account of speculation in the 1920s and 1930s that it might be the ‘royal palace’ of TúathalTechtmar, who in pseudo-historical tradition is credited with establishing the ‘fifth’ (cóiced) of Mide. SeeR.A.S. Macalister & R.L. Praeger, ‘The excavation of Uisneach’ (1928–9), 125–7; R.A.S. Macalister, AncientIreland (1935), pp 104–6. 6 Macalister & Praeger, ‘The excavation of Uisneach’; idem, ‘The excavation

88 Roseanne Schot

about the late seventh/eighth century and the eleventh century AD, with someindications of later activity extending into the medieval period.7 The primaryphase of occupation at Togherstown was focused on a series of paved areasbounded by stone walls in the inner enclosure8 and two elaborate souterrains, withassociated finds including an ornate, openwork disc-brooch of gilt bronze, acrutch-headed ringed pin and a decorated bone comb. At approximately 80m indiameter, it is the largest of some half a dozen enclosures located on the lowerslopes of Uisneach, several of which appear to be early medieval ringforts also.These include the nearby bivallate site known as ‘Rathfarsan’ and another, single-banked enclosure on the south-west shoulder of the hill, in Kellybrook townland.

Significant though these enclosures are, all of them are overshadowed by themore prominently sited Rathnew Enclosure on the eastern summit of Uisneach(pl. 4, fig. 5.1). Comprising a large, sub-circular enclosure, almost 90m in diameter,with a smaller, semi-circular annexe joined to its western side, Rathnew Enclosure

of an ancient structure’ (1929–31). 7 R. Schot, ‘Uisneach Midi’ (2006); idem, ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’(2008), i, 207–31. 8 These were interpreted as open-air ‘courts’ by the excavators, although some may bethe remains of buildings.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 89

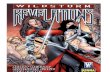

5.1 Aerial view of Rathnew Enclosure, from the southeast. The remains of one of the earlymedieval houses and several later field boundaries are visible in the larger, eastern segment of

the conjoined ringfort (photo courtesy of the Department of Archaeology, NUI Galway).

is the most substantial early medieval earthwork at Uisneach and indeed thelargest upstanding monument in the complex as a whole. Aligned on theenclosure but terminating a short distance to its south is an embanked roadwaywhich forms the principal approach to the summit of Uisneach today. Althoughthere is reason to suspect that this so-called ‘ancient road’ may be one of latestmonuments constructed at Uisneach, the possibility of contemporaneity withRathnew Enclosure cannot be ruled out.9

The 1920s excavations at Rathnew Enclosure revealed the remains of severalhouses, two souterrains and various other features associated with domestic occu -pation spanning several centuries.10 Whether the site was occupied continuouslyor intermittently was never established. A more surprising discovery, perhaps, wasthat the eastern part of the ringfort was built over an earlier enclosure comprisinga penannular ditch measuring some 50m in diameter, and a range of associatedfeatures including a series of pits and post-holes in its interior.11 In a detailedreappraisal of the site, I have suggested that this was a ceremonial enclosure of lateIron Age date (c.fourth–fifth century AD) and that it was deliberately incorporatedinto the later ringfort in late seventh or eighth century AD.12 The evidence ofdomestic occupation coinciding with a time when the Clann Cholmáin were verymuch in the ascendancy also prompted the suggestion that the ringfort may havebeen a royal residence, albeit one of several on a royal circuit that also included thebroadly contemporary settlements of the Clann Cholmáin at Lough Ennell, about10km to the south-east. In contrast, however, to the more strategically situatedsettlements of Dún-na-Sgiath and Cró Inis at Lough Ennell, this ringfort was builton sacred ground, at a time when contemporary literary sources invest the hillwith a potent, ritually charged symbolism. Its construction, therefore, may wellhave been motivated by a desire on the part of the kings of Uisneach to legitimizetheir rule by establishing not just an ideological link with the past, but a physicalone also. The possibility that royal occupation at Uisneach was restricted toperiods of ceremonial occasion, such as inauguration and assembly – events inwhich some of the older monuments in the complex may also have played a role– thus emerges as a very feasible scenario.

Adopting an interpretive and avowedly holistic approach, this essay explores theevolving role of Uisneach from cult centre to royal centre, focusing in particularon how ‘the past’ was accommodated, drawn upon and in some cases wholly re-composed to facilitate this transition. That this was a process marked by ablending of old and new becomes readily apparent when assessing the variousinterwoven elements – archaeological, topographical, mythological, toponymic

9 Schot, ‘Uisneach Midi’, 45, 48–50. 10 Macalister & Praeger, ‘The excavation of Uisneach’. 11 Ibid.,87–91. 12 Schot, ‘Uisneach Midi’.

90 Roseanne Schot

and historical – that played a role in shaping the landscape both physically andconceptually. Indeed, the common prism through which many archaeologists,mythologists, literary scholars and medieval historians nowadays approach theirsubject matter is itself an acknowledgment of the common language ofmonuments, material culture, myths and texts. All are expressions of the samediscourse, composed in specific cultural and historical contexts and embodyingcontemporary ideological concerns and aspirations. Far from being either randomor formulaic, moreover, the motifs used to express these concerns are chosen withintention as appropriate symbols for conveying particular meanings, whetherthrough the medium of myth or in the form and layout of monuments. AsHodder astutely observes, for instance, ‘There can never be any direct predictiverelationships … because in each particular context symbolic principals and generaltendencies for the integration of belief and action are rearranged in particular waysas part of the strategies and intents of individuals and groups’.13 While suchintentions are often more explicit and easier to ‘read’ in textual sources than inother media, it is widely recognized that monuments can also be used to makevery effective social, political and religious statements.

Quite distinct from viewing the treatment of Uisneach in early medievalliterature as a form of contemporary commentary is the more contentious issue ofthe extent to which the underlying structures of myths may preserve elements ofolder, pre-Christian beliefs and traditions. While this is a field of study that hastraditionally been dominated by ‘nativist’ scholars who tend to stress theconservatism of native tradition and its continuity with a pagan past, in morerecent years commentators such as McCone14 have begun to advocate the majorrole of monastic scholars in the compilation of all genres of literature and theChristian influences apparent in early medieval texts. However, it appears thathistorians and literary scholars by and large agree that despite ‘censorship, revisionand deliberate omission’ on the part of Christian redactors, some residual motifsor themes of pre-Christian origin remain.15 Indeed, if such explicitly pagan motifsas the symbolic marriage of the king and sovereignty goddess could be accom -modated, then it is by no means unreasonable to imagine that other traditionsmore amenable to Christian assimilation might also be preserved. Certainly, thisis an area where each case needs to be assessed on its own merits and one in whichmulti-disciplinary studies clearly have a major role to play.

13 I. Hodder, Symbols in action (1982), p. 217. 14 K. McCone, Pagan past (1990). 15 See, for example,C. Doherty, ‘Kingship in early Ireland’ (2005), and the essays in this volume by Marion Deane, ‘Fromsacred marriage to clientship’, Muireann Ní Bhrolcháin, ‘Death-tales of the early kings of Tara’, andBridgette Slavin, 'Supernatural arts, the landscape and kingship'.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 91

A LANDSCAPE CONCEIVED

Countries have their factual and their mythical geographies. It is not alwayseasy to tell them apart, nor even to say which is more important, because theway people act depends on their comprehension of reality, and that compre -hension, since it can never be complete, is necessarily imbued with myths.16

The Hill of Uisneach is a broad and imposing limestone ridge almost midwaybetween Ballymore and Mullingar in Co. Westmeath, and thus lies – ratherfittingly – at the approximate centre of Ireland (pl. 3). In some early sources,Uisneach is portrayed as the meeting place of the five ancient provinces, consistingof Ulster, Leinster, Connacht and Munster, the latter divided into two halves,either east–west or north–south. These and other alternative schema that purportto describe a proto-historic, five-fold division of the island become increasinglyelaborate from about the tenth century, and have been shown to reflect a specificideological agenda associated with the Uí Néill kings of Tara.17 Indeed, whateverthe historical veracity of a bipartite division of Munster, the dominant alternativetradition, which identifies Mide as the elusive ‘fifth’ province centred on Tara,appears to have no historical basis whatsoever. O’Rahilly has noted that the name‘Mide’ was originally used to denote not a province but a district of landimmediately surrounding the Hill of Uisneach,18 and there is in fact considerableevidence to demonstrate that, up until at least c.AD500, the midland regioncomprising Cos Longford, Westmeath and Meath formed part of the ancientprovince of Leinster.19 An early annalistic reference, possibly written in the latesixth century,20 explains how campus Mide, ‘the plain of Mide’, was wrested fromthe Laigin (Leinster) in AD516 by Fiachu mac Néill, the eponymous ancestor ofthe southern Uí Néill dynasty of Cenél Fiachach. Both Tírechán and the VitaTripartita show St Patrick encountering Fiachu and his kin at Uisneach, while thechurches founded by Áed mac Bricc (d. 589) – the principal saint of CenélFiachach21 – at Cell Áir (Killare), at the foot of the Hill of Uisneach, and RáithÁeda (Rahugh), on the border between Westmeath and Offaly, further reinforcethe dynasty’s ties with this locale.

16 Y.-F. Tuan, Space and place (1977), p. 98. 17 Byrne, Irish kings, pp 46–7; R.M. Scowcroft, ‘LeabharGabhála – part ii’ (1988), 49–53; N.B. Aitchison, Armagh and the royal centres (1994), pp 106 –30; D. ÓCróinín, ‘Ireland, 400–800’ (2005), especially pp 187–8. On the early literature pertaining to the fiveprovinces, see A. Rees & B. Rees, Celtic heritage (1961), pp 118–39. 18 T.F. O’Rahilly, Early Irish historyand mythology (1946), pp 167, 171. 19 See, for example, F.J. Byrne, The rise of the Uí Néill (1969), p. 12;A.P. Smyth, ‘Húi Néill and the Leinstermen’ (1974); idem, ‘Húi Failgi relations with the Húi Néill’ (1974);A.S. Mac Shamhráin, Church and polity (1996), especially pp 51–65; Charles-Edwards, Early ChristianIreland, pp 155–6, 447–58. 20 AU, pp 62–3. See also Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp 450–3,463–4; P. Byrne, ‘Certain southern Uí Néill kingdoms’ (2000), 6. 21 Mac Shamhráin & Byrne,

92 Roseanne Schot

Sometime in the late seventh century, following a lengthy struggle among theincipient Uí Néill dynasties for control of the ‘plain of Mide’, Cenél Fiachach wereeclipsed by their kinsmen, Clann Cholmáin, although their actual territorial lossesappear to have been largely confined to the immediate vicinity of Uisneach.22

With the expansion of Clann Cholmáin’s power in the eighth century, Mideevolved into a vast over-kingdom encompassing all of modern Westmeath, as wellas parts of Longford and Offaly, and at the end of the tenth century, when MáelSechnaill mac Domnaill succeeded in extending the dynasty’s sphere of influenceeastwards, the meaning of the name was broadened further to include Brega.23 Itis this much enlarged over-kingdom of Mide (‘Meath’), containing both Uisneachand Tara within its orbit, that we see reflected in the likening of these dual centresto ‘two kidneys in a beast’ and the declaration that ‘it was right to take the fiveprovinces of Ireland from Tara and U[i]snech’.24

Yet, the perception of Uisneach as the centre-point of Ireland could just as wellbe based on an older tradition that places far greater emphasis on its role as thecentre of the cosmos, an axis mundi.25 It is this concept of centrality that is mostpervasive in the early literature, with Uisneach consistently portrayed as a place oforigins and beginnings, linked to the Otherworld; as a place where druidic andother divinely inspired judgments and proclamations are made, particularlyregarding the cosmological divisions of the island; as a place of assembly, withtraditions of a fire-cult; and as the site of an omphalic stone, a mystical well and asacred tree.26 Certainly, the very name ‘Mide’, recorded in the earliest written sources,implies that some conception of the medial position of Uisneach was alreadycurrent by the late sixth century, and this is continually reinforced by the widelyused place-name Uisnech Mide, which has been variously translated as the‘temples’/‘angular place’27 or ‘hearth’28 ‘in the middle’. Closely reminiscent of theGallic medionemeton, ‘central sanctuary’,29 each of these designations is fitting in

‘Prosopography I’, pp 218–20. On Ráith Áeda, see E. FitzPatrick, ‘The landscape of Máel Sechnaill’s rígdál’(2005). 22 P. Walsh, Placenames of Westmeath (1957), pp 245–9, 341–2, passim; Byrne ‘Certain southernUí Néill kingdoms’, 242–59; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp 28, 446, 554–5; Mac Shamhráin,‘The emergence of Clann Cholmáin’; Schot, ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’, i, 44–58. 23 F.J. Byrne, ‘Thetrembling sod’ (1987), p. 19. 24 R.I. Best (ed.), ‘Settling of the manor of Tara’ (1910), 152–3, §32, 154–5, §34. 25 Rees & Rees, Celtic heritage, especially pp 156–63; C. Doherty, ‘The monastic town’ (1985).See also O’Rahilly, Early Irish history and mythology, pp 171–2; idem, ‘Notes on Early Irish history andmythology’ (1950). 26 See discussion and references below. The sacred tree of Uisneach, Bile Uisnig (orCraeb Uisnig), is ascribed a cosmological significance in the tale Do Shuidigiud Tellaich Themra, where it isidentified as one of the five legendary trees of Ireland that sprung from the berries of a single branch: Best,‘Settling of the manor of Tara’, 150–1, §29. According to dindshenchas, ‘the Ash of populous Uisnech’ wasfelled ‘in the time of the sons of Áed Sláine’: MD, iii, pp 148–9. For further discussion of the cosmologicaland royal symbolism associated with sacred trees, see A.T. Lucas, ‘The sacred trees of Ireland’ (1963); A.Watson, ‘The king, the poet and the sacred tree’ (1981); Doherty, ‘Kingship in early Ireland’, pp 14–17.27 O’Rahilly, Early Irish history and mythology, p. 171. 28 J. Vendryes, Lexique étymologique (1978), pp 21–2.29 J. Brunaux, The Celtic Gauls (1988), p. 7.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 93

its own way. Uisneach’s association with fire, for example, is well known;according to dindshenchas, it is the place where Mide, the chief druid of Nemed,lit the sacred flame that ‘shed the fierceness of fire … [for seven years] over thefour quarters of Erin’,30 while elsewhere we see the landscape shrouded in a ‘cloudof fire’31 and ‘five streams of fire’ emanating from its hinterland.32 The pseudo-etymology provided for Uisnech in dindshenchas – ós neoch, which has beentranslated by the editor as ‘over somewhat’33 – is also potentially significant as itmay bear some reference to the physical elevation of the hill and its unrivalledprospect over the central plain of Ireland. It is a vista frequently invoked indescriptions of the medial status of the hill and one most commonly expressedwith reference to the four cardinal points. Thus, in his manifestation as an all-seeing sun-god in Tochmarc Étaíne (‘The Wooing of Étaín’), for example, we aretold of the wide prospect over which the Dagda presides at Uisneach, with ‘Irelandstretching equally far from it on every side, to south and north, to east and west’.34

Representations of this nature seem to point to a cosmological structure based onwhat Yi-Fu Tuan describes as ‘oriented mythical space’, which places the individualat the centre of the universe:35 in this instance with the four directions orientedaround a central axis: ‘here’ – the point of observation. By ignoring ‘the logic ofexclusion and contradiction’ that characterizes more pragmatic, scientificconceptions of space, moreover, mythical representations allow for the coexistenceof multiple ‘centres’, although, as Tuan notes, ‘one center may dominate all theothers’.36 This inherent flexibility may provide the key to understanding howcosmological schema can be accommodated quite readily within evolvinggeopolitical frameworks, while simultaneously transcending corporeal divisions.

As a number of scholars have noted, the identification of Uisneach as the ‘navel’of Ireland in early literature is paralleled by representations of the centre of thecosmos as a mountain, a pillar, a fire-altar, a tree or a well of life in many othercultures and religious traditions around the world.37 Some of the places previouslysingled out for mention in this context include sites in Wales, France, Rome,Greece, Jerusalem, India and China, and there are clearly others, as MarieLecomte-Tilouine’s essay in this volume amply illustrates.38 This suggests thatsocieties in Ireland were participant to a ‘cult of the centre’ that is almost universal,

30 MD, ii, pp 42–3, ll. 9–16. 31 W. Stokes (ed.), ‘Togail Bruidne Da Derga’ (1902), 32, §25. 32 Themystical flame from which five streams of fire burst forth was created by Delbaeth (‘shape of fire’) at CarnFiachach meic Néill (Carn td, barony of Rathconrath), approximately 2km south of Uisneach. See W. Stokes(ed.), ‘Cóir Anmann’ (1897), pp 358–9, §159; MD, iv, pp 278–81 (Loch Lugborta). 33 MD, ii, pp 44–5, l. 43. 34 O. Bergin & R.I. Best (eds), ‘Tochmarc Étaíne’ (1938), 144–5, §5. 35 Tuan, Space and place,pp 90–6. 36 Ibid., p. 99. 37 Rees & Rees, Celtic heritage, pp 156–63; Doherty, ‘The monastic town’,pp 46–52. For broader parallels, see also, for example, M. Eliade, Myth of the eternal return (1954), pp 12–21; idem, Patterns in comparative religion (1958), pp 231–8, 367–87 (including bibliographies); J.C.Heesterman, ‘Centres and fires’ (1992); Doherty, ‘Kingship in early Ireland’. 38 Rees & Rees, Celtic

94 Roseanne Schot

and raises the very intriguing prospect that the perception of Uisneach as an axismundi was at one time fundamental to its role and significance.

Yet, however universal some of these motifs may be, what grounds them andmakes them meaningful in a native context is the specific manner in which theyare inscribed in the landscape. As well as fire, for example, Uisneach is also closelyassociated with water, a relationship that reconciles well with its geographicalposition at the junction of two major river systems, in a landscape hemmed in onall sides by bodies of water: the River Inny and its tributary, the Dungolman, tothe north and west, and Lough Owel, Lough Ennell and the River Brosna, to theeast and south. In addition to myriad other, social, cultural and economicsignificances attaching to these watery features – as communication arteries, assources of food and other resources, and as socio-political boundaries – it is clearfrom their nomination as foci for votive deposition in prehistory39 and theirassociated mythology that many of them were also invested with more profound,symbolic and sacral significances. In one of the more colourful toponymicaccounts contained in Lebor Gabála Érenn, for example, Loughs Owel and Ennell,together with Lough Iron, to the north, are said to have issued from ‘three belches’vomited from the Hill of Uisneach by the recipient of an emetic potion preparedby the legendary physician Dian Cécht.40 While this account may embody a subtlereminder of the territorial claims of Clann Cholmáin (though by no meansreflecting the full extent of the over-kingdom of Mide), of perhaps greater interesthere is its depiction of Uisneach as a source of primeval waters, a motif that alsofinds expression in other literary sources dating from the late seventh centuryonwards. The tale Tucait Baile Mongáin (‘Mongán’s Frenzy’), for instance,describes how a great hailstorm during an assembly on the hill ‘left twelve chiefstreams in Ireland for ever’,41 and is also one of the earliest sources to emphasizethe liminal status of Uisneach as a meeting point between the temporal andotherworld spheres. A similar sentiment is expressed, though in a different guise,in Echtrae Chonlai (‘The Otherworld Adventures of Conlae’) and it has beensuggested that both tales were composed in the late seventh century by an authorbased in the midlands.42

heritage, pp 157–63, 175–6; Doherty, ‘The monastic town’, pp 46–52; M. Lecomte-Tilouine, ‘Imperialsnake and eternal fires’, this volume. 39 Schot ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’, i, 257–86. 40 LGÉ, iv,pp 136–7, §319. Uisneach is referred to in this passage as Cnoc Uachtar Archae (‘Upper Hill of Erc’), a namealso used for the hill in Acallam na Sénorach: see S.H. O’Grady (ed.), Silva Gadelica, ii, p. 158; A. Dooley& H. Roe (trans), Tales of the elders of Ireland (1999), p. 70. 41 K. Meyer (ed.), The voyage of Bran (1895–7),i, pp 56–7. See also J. Carey, ‘Some Cín Dromma Snechtai texts’ (1995). 42 Carey, ‘Some CínDromma Snechtai texts’. See also discussion on Echtrae Chonlai in Bridgette Slavin’s essay, 'Supernaturalarts, the landscape and kingship’, pp 77–8, this volume.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 95

A particularly striking feature of these and other representations of Uisneach asa place of ‘origins’ is that they harmonize so closely with tangible, physical realities.As alluded to above, Uisneach is in fact surrounded on all sides by a dense networkof streams and minor rivers that drain either northwards to the River Inny orsouthwards to the Brosna and, what is more, is itself the source of several curiouswatery features. The most conspicuous of these is a large pond fed by anunderground spring that occupies a slight hollow midway along the crest of thesummit (pl. 4), with gently rising ground to the west, east and south. Knownlocally as ‘Lough Lugh’, this is almost certain to be the body of water identified indindshenchas as Loch Lugborta, where the god Lug is said to have been ‘killed anddrowned’ during an assembly on Uisneach by the divine trio, Mac Cuill, MacCécht and Mac Gréine.43 Two other springs, Tobernaslath (‘Well of the Rods’) andSt Patrick’s Well, each a bountiful source of clear, flowing water, occur on theundulating, southern slopes of the hill. The names of both springs were firstrecorded in 1837 by John O’Donovan, who was also the first to identifyTobernaslath as ‘the Spring of Usnagh’ named In Finnflescach (‘the Bright andFlourishing Spring’) in the late twelfth-century tale Acallam na Senórach.44

Representing yet another exposition of the otherworldly attributes of the hill, therelevant passage relates how Oisín, the legendary fían warrior, attained to thespring, containing ‘eight speckled salmon of great beauty’, which ‘From the timeof the battle of Gabair to that time none of the men of Ireland had found’.45 Thesudden appearance in recent decades of another large pond on the southern slopeof Uisneach is also noteworthy, as this is a phenomenon that perhaps hadprecedents in antiquity and may, in such an instance, have served to furtherenhance the supernatural aura of the hill.

The depiction of Uisneach as a source of primordial waters represents but onemanifestation of a more widespread ‘symbolism of the centre’ that is perhaps mostevocatively expressed by the omphalic stone called umbilicus Hibernie, the ‘navel ofIreland’, by Giraldus Cambrensis,46 and earlier still described as the meeting pointof the five ancient provinces. This stone, which is said to have been divided intofive by the points of the provinces running towards it,47 is no mere figment of theimagination but rather has long been identified with a massive, fragmented glacialerratic on the western slope of Uisneach, nowadays popularly known as the ‘CatStone’ (pl. 5). A very conspicuous landmark, measuring over 4m in height and 5min breadth, the stone must have attracted attention from the earliest times, and

43 MD, iv, pp 278–81. 44 M. O’Flanagan (comp.), Letters … county of Westmeath (1931), i, p. 42. Thespring is marked ‘Tobernaslath (Finnleascach)’ on the 1838 edition of the Ordnance Survey six-inch map;St Patrick’s Well is also shown but is not named. 45 Dooley & Roe, Tales of the elders of Ireland, p. 72.46 J.J. O’Meara (ed.), ‘Giraldus Cambrensis in Topographia Hibernie’ (1949), 159; idem (trans.), Thehistory and topography of Ireland (1982), p. 96, §88. 47 Best, ‘Settling of the manor of Tara’, 154–5, §33.

96 Roseanne Schot

over the course of its life-history is likely to have been imbued with a wide rangeof meanings.48 As the most prominent by far of a vast assortment of stone erraticsand outcrops strewn across the hilltop, it is almost certain to be the stone calledPetra Coithrigi, ‘Patrick’s Rock’, by Tírechán (c.690) and the feature that inspiredthe cursing of ‘the stones of Uisnech’ in the ninth-century Vita Tripartita.49

Although the stone is now understood to be of natural derivation, there areindications that, up until relatively recently, its origins may have been morecommonly explained by reference to distant ancestors, divine beings or animportant cosmological event, thus reinforcing the link between people and theland they inhabited. This is suggested quite explicitly in the Middle Irish tale DoShuidigiud Tellaich Themra (‘The Settling of the Manor of Tara’), which relates howthe stone was ‘set up’ and a forrach was marked out during the reign of Diarmaitmac Cerbaill as king of Tara (?544/5–65), to proclaim, in a very visual way, thetime-honoured status of Uisneach as the ‘navel’ of Ireland.50 O’Donovan’s remarkthat the stone had been remodelled to form ‘a splendid cromlech’, on which ‘thepagan Irish … offer[ed] sacrifices’,51 demonstrates that belief in a human elementto its design endured well into the nineteenth century, and is a potent reminderthat our tendency to distinguish between ‘culture’ and ‘nature’ – built and naturalfeatures of the landscape – is a relatively recent, and mainly ‘western’, departureand represents a way of viewing the world that is unlikely to have been shared bypeople in the past. Indeed, as Richard Bradley succinctly states with reference tostone features in particular, ‘Perhaps the very distinction between [ruined]buildings and natural features is inappropriate in studying societies which lackeda modern understanding of geology’.52 The relevance of this observation isstrikingly illustrated in the case of Uisneach, a place where ‘natural’ features,perhaps more than monuments, take centre-stage.

DWELLING ON THE PAST: THE PREHISTORIC ARCHAEOLOGY OF

UISNEACH

Alongside the various natural wonders of the hill, this is a landscape rich inarchaeological remains. Of the twenty or so monuments still visible at Uisneach,more than half appear to be prehistoric, and to this group can be added over adozen others that have come to light as a result of geophysical survey in recent

48 Schot, ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’, i, 243–50. 49 L. Bieler (ed.), Patrician texts, pp 136–7, §16; K.Mulchrone (ed.), Bethu Phátraic (1939), pp 50–1, ll. 867–73. On the name Coithrigi, see G. MacEoin, ‘Thefour names of Patrick’ (2002); Doherty, ‘Kingship in early Ireland’, pp 9–11. 50 Best, ‘Settling of themanor of Tara’, 150–5, §§30–3. 51 O’Flanagan, Letters … county of Westmeath, i, pp 25, 41.52 R. Bradley, ‘Ruined buildings, ruined stones’ (1998), 13.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 97

years.53 Collectively, they include a cairn, a number of possible standing stones anda range of barrows and enclosures, most of which are concentrated on and aroundthe summit – a broad, east-west ridge about 1km long and 500m wide, with agently rounded rise at either end (fig. 5.2). Several of the monuments are

53 Schot, ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’, i, 97–149, 232–54; ii, 304–25; and see discussion below.

98 Roseanne Schot

5.2 Map of the archaeological complex at Uisneach showing principal monuments and features.

mentioned in early documentary sources and it is clear that those who engagedwith, and indeed occupied, Uisneach during the early medieval period were notonly aware of their presence, but actively harnessed – and reworked – thesignificances invested in them. This is indicated quite clearly, as we shall see, bythe manner in which the ancient remains are treated in the literature, and isperhaps also implied by the largely unobtrusive positioning of most of the earlymedieval enclosures with respect to older monuments. The only notable exceptionis, of course, the possibly ‘royal’ enclosure of Rathnew which, in addition toincorporating an earlier ceremonial monument, occupies a commanding positionin the midst of the prehistoric complex on the summit of Uisneach, a choice oflocation that speaks more to ideology than pragmatism.

Although there are outstanding questions regarding the dating of manymonuments at Uisneach, it is quite evident that the sacral significance of the hillwas established early in prehistory, and subsequently sustained over manymillennia. Crowning the highest point of the hill, on the western summit (180mabove sea level), for example, is a derelict stone structure known as ‘St Patrick’sBed’, a name first recorded by O’Donovan54 and one presumably inspired bylegends describing the saint’s visit(s) to Uisneach. Today it appears as a low, sub-rectangular, partly grass-covered cairn, about 9m in length (north–south), whichis delimited in places by low orthostats and appended on its western side by acourt-like feature defined by two rows of upright stones (fig. 5.3). While itsdilapidated condition makes precise classification difficult, this structure islikely to represent the remains of a megalithic tomb of one type or another.Significantly, geophysical survey around the monument has revealed a host ofinteresting sub-surface features, including the footprint of what appear to be twoearlier, circular enclosures (23m and 35m in diameter) defined by timber palisades(fig.5.4). The overall arrangement is reminiscent of the palisade trenchesidentified in pre-tomb levels at Tara (Mound of the Hostages) and Knowth,55 andostensibly links Uisneach with a select group of multi-period ceremonial sites inIreland where structural activity pre-dating the construction of a megalithic tombis attested.

The presence of a cluster of potential ring-ditches56 surrounding St Patrick’sBed, moreover, as well as a ring-barrow and a low mound a short distance to itsnorth and south respectively, may imply that distant ancestors and traditions

54 O’Flanagan, Letters … county of Westmeath, i, p. 42. 55 M. O’Sullivan, Duma na nGiall (2005), pp23–7; G. Eogan, Excavations at Knowth 1 (1984), pp 219–27; G. Eogan & H. Roche, Excavations at Knowth2 (1997), pp 7–9, 44–5. 56 The ring-ditches, evidenced as relatively small, annular or semi-circulargeophysical anomalies (8–12m in diameter), are for the most part very ephemeral features, although theoccurrence of other, more clearly-defined examples elsewhere on Uisneach raises confidence in theiridentification as bona fide archaeological features.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 99

100 Roseanne Schot

5.3 The possible megalithic tomb known as ‘St Patrick’s Bed’, with an Ordnance Surveytrigonometric station on its summit, viewed from the southwest.

rooted in older monuments retained an importance, or indeed attracted newsignificances. The relative chronology of these monuments and their relationshipsto one another is difficult to ascertain, however; ring-ditches and simple,unelaborated mounds are among the most enduring forms of funerary and ritualmonuments used in Ireland, while ring-barrows, though regarded primarily as anIron Age phenomenon, appear to have had quite a lengthy currency as well,extending back to the early Bronze Age.57 This clearly limits the potential for therelative dating of monuments at Uisneach – a problem not restricted to barrows –and leaves significant gaps in our understanding of how the archaeologicalcomplex evolved over time. Yet, when viewed collectively, the broad chronologicalrange of monuments at Uisneach nevertheless raises the prospect of generalcontinuity, and this is supported, at least for the later part of its history, by theevidence from the large-scale excavations at the Rathnew and Togherstownenclosures.

57 For a summary of the dating evidence relating to barrows, see Newman, Tara, pp 153–70. See also J.Waddell, Bronze Age burials of Ireland (1990); idem, Prehistoric archaeology of Ireland (1998), especially pp161, 365– 9.

Of greater concern here than the date of their construction is how ‘ancient’monuments that retained a physical presence in the landscape were laterinterpreted, and perhaps even actively reused, sometimes long after their originalpurpose was forgotten. Patterns such as clustering and overlapping and, in somecases, the wholesale incorporation of pre-existing monuments into new onesdemonstrate in a very visible way the importance of ‘the past’ in the past, and thisis also seen in the mythology and naming of ancient monuments. Indeed,nowhere at Uisneach is this phenomenon more strikingly illustrated than at theCat Stone, which at some time in the past was augmented by the construction ofan earthen enclosure around it. The enclosure, defined by a broad, circular earthen

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 101

5.4 Greyscale image of geophysical survey on the western summit of Uisneach, showing themagnetic footprint of two previously unrecorded enclosures and other archaeological featuresbeneath the imprint of modern cultivation. The smaller (23m) enclosure partly underlies StPatrick’s Bed, whose position corresponds with the white (unsurveyed) area at the top centre

of the image.

bank (21m in diameter) with no visible sign of an entrance, appears to have beencreated principally from material scarped outwards from around the stone at itscentre. In terms of its basic morphology, it shares affinities with a diverse group ofritual and funerary monuments that includes embanked enclosures and someforms of barrow, indicating a very broad potential date-range for this monumentextending from the later Neolithic period into the first millennium AD.58 On amore specific level, however, the site appears to be unique in Ireland in the sensethat it is, as far as I am aware, the only enclosure of its kind to incorporate amassive, glacial erratic at its centre. Yet, by considering the Cat Stone and itssurrounding enclosure as individual ‘monuments’ in their own right, theirjuxtaposition can be seen to be far less unorthodox than at first anticipated.

The construction of the enclosure around the stone clearly marks it out as aplace of special significance, and may have been driven by a desire to enhance,contain and control the stone’s potency and meaning. When this event took place,and whether it marks a radical shift in the meaning(s) attributed to the stone orsimply a desire to reinforce its long-established significance is, of course,unknown. One obvious possibility, however, is that the addition of the enclosurewas linked to the development of the tradition that identifies the stone as thenavel or omphalos of Ireland. As we have seen, the tale Do Shuidigiud Tellaich Themratells how the erection of the ‘pillar-stone of five ridges’ on Uisneach wasaccompanied by the marking out of ‘a portion of each province’ with a forrach, aterm signifying an area ‘cut off ’ for protection or sanctuary, and bearing a meaningsimilar to Latin templum and Greek temenos, ‘sacred enclosure’.59 There can belittle doubt that it was used by the author of the text to denote the earthworksurrounding the stone, and while it would be imprudent to regard the eventsdepicted in the text as historical fact, there is no real obstacle to supposing that theenclosure was indeed constructed for the purpose stated, either during the earlymedieval period or before. Whatever the case, the prominence and significanceascribed to the stone in early literary sources of varying date is testimony to itscontinuing importance, and the possibility that it provided a focus for kinglyritual is certainly worth considering; a point I will return to below.

The same may yet be true of another conspicuous monument, in this caselocated on the eastern summit of Uisneach. Here, a prominent mound, about1.7m high and 20m in diameter, crowns the gentle rise next to Lough Lugh andis probably the monument identified in dindshenchas as Carn Lugdach or theSídán, where the god Lug was reputedly buried after being drowned in the nearbylake during an assembly (pls 4, 6).60 The reported discovery of a cist within the

58 Schot, ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’, i, 247–9. 59 Doherty, ‘The monastic town’, pp 48–51ff. See alsoD. Mac Giolla Easpaig, ‘Significance and etymology of the placename Temair’ (2005), pp 442–3. 60 MD,

102 Roseanne Schot

mound sometime prior to the 1920s61 suggests that this may be a bowl-barrow ofearly Bronze Age date. Although it is the only monument visible on this part ofthe hill today, geophysical survey in 2005 revealed a wealth of sub-surface featuresand other traces of activity around it.62 One of the most intriguing was an arc-shaped feature that corresponds with a shallow depression skirting the edge of the

iv, 278–9. 61 Macalister & Praeger, ‘The excavation of Uisneach’, 83, no. 15. 62 Schot, ‘Uisneach, Co.Westmeath’, i, 138–41.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 103

5.5 Map of the eastern summit of Uisneach showing the magnetic signature of the 200mditched enclosure and its central mound, as well as a host of other features revealed by

geophysical survey.

rise just to the east of Lough Lugh, which further survey has now confirmedrepresents part of a very large, sub-circular enclosure surrounding the entireeastern summit of the hill (fig. 5.5).

At approximately 200m in overall diameter, the enclosure is truly monumentalin scale and clearly represents a major addition to the corpus of knownmonuments at Uisneach. Straddling the boundaries of three adjoining townlands,the north-west quadrant of the enclosure, and much of its southern sector, arenow obscured by the stone walls that divide Mweelra from Ushnagh Hill andRathnew, respectively. For most of its circuit, however, the enclosure is expressedas a curvilinear magnetic band, 2m in average width. The geophysical andtopographical evidence suggest that it is defined by a substantial, probably rock-cut, ditch whose fill may contain significant quantities of burnt material. Thegeophysical signature of the enclosure on the east and south-east is noticeablyweaker than elsewhere along its circuit, possibly due to more intensive agriculturalactivity in this area in recent centuries, which may have resulted in the truncationof the uppermost levels of the enclosure ditch here. Notwithstanding thisdisturbance, the entrance to the enclosure is clearly visible on the east-north-east,and comprises a gap, some 4m wide, defined on either side by a distinctive,inward-curving terminal. The entrance aligns on the prominent mound on thesummit, which occupies a central position within the enclosure.

That this is a ceremonial monument is readily apparent from its size, the presenceof a mound of possible early prehistoric date at its centre and its location within abroader complex of funerary and ritual monuments. Indeed, the sheer scale of themonument – the largest yet identified at Uisneach – as well as aspects of its design,invite close comparison with sites such as Tara, Emain and Rathcroghan, wherelarge-scale enclosures with internal mounds are a recurring feature. As well as sharingnotable features in common, some variation in the form and construction of thesemonuments is also apparent. In contrast to the internally ditched earthworkenclosures built during the first century BC at Tara (Ráith na Ríg), Emain (NavanFort) and possibly Dún Ailinne, no traces of an earthen bank accompanying theditch have come to light at Uisneach. Although the possibility that such a featureonce existed and was subsequently levelled by ploughing should not be overlooked,such a hypothesis is not readily supported by the morphology of the survivingsection of the monument on the west, an area undisturbed by cultivation. In thisrespect at least, the 360m ditched enclosure surrounding Rathcroghan Mound63 mayprovide a closer parallel for the Uisneach enclosure. While excavation is clearlyrequired to verify the dating of some of these monuments, on the basis of presentevidence a later prehistoric date seems the most plausible.

63 Waddell et al., Rathcroghan, pp 143 (fig. 5.5), 146–8.

104 Roseanne Schot

ON MIDDLE GROUND: UISNEACH IN LATE PREHISTORY

While the overall picture provided by the prehistoric remains and later literarysources is of a landscape whose sacred character was established and maintainedover many millennia, the relative dearth of reliable, excavated evidence fromUisneach means that in most instances the nature of activity associated withindividual monuments can only be inferred from the character of the monumentsthemselves. Structures such as St Patrick’s Bed and the various barrows and ring-ditches, for example, suggest that an important aspect of Uisneach’s role inprehistory was sepulchral: it was, or so it would appear, a necropolis. Yet despitethe partial excavation of at least three barrows on Uisneach by Macalister andPraeger, we have no direct evidence – apart from the possibility that one of themcontained a cist – of the form that any funerary or other, ritual activity associatedwith these monuments may have taken. In fact, the only human remains recordedfrom Uisneach were found, not in a burial monument, but in the ditch andinternal area of the penannular enclosure underlying the conjoined ringfort ofRathnew. As well as two extended inhumations of unknown (but possiblymodern) date, these include a fragment of a child’s skull and several other unburntbones of a child/adolescent that may have derived from a disturbed context and/orhave remained in circulation as relics prior to their deposition, as evidenced in thecase of the skull fragment from the later Iron Age horizon at Raffin Fort, Co.Meath.64 Other ritually charged activities involving feasting, the lighting of greatfires and possible animal sacrifice also took place within the penannular enclosureat Uisneach.65 The date at which these events appear to have taken place (the lateIron Age) makes it quite conceivable that collective memory of such practicesinformed the tradition preserved in early literature that Uisneach was a place ofassembly, associated, among other things, with a fire-cult. The presence of aRoman-type barrel padlock key at the site, which may have been associated withthis early phase of activity, as well as a mid-fourth-century AD coin of the emperorMagentius, provenanced simply to ‘Uisneach’, is also of interest, given thefrequent occurrence of Roman material at pre-Christian ceremonial centresincluding Tara, Newgrange, Dún Ailinne, Freestone Hill (Co. Kilkenny) andClogher (Co. Tyrone).66

The evidence from the penannular enclosure is clearly of importance inproviding some insights into the nature of later prehistoric activity at Uisneach,

64 Schot ‘Uisneach Midi’, 53–4, 59, 61. On the skull fragment from Raffin, see C. Newman, ‘Sleeping inElysium’ (1993), 22; C. Newman, M. O’Connell, M. Dillon & K. Molloy, ‘Interpretation of charcoal andpollen data’ (2006); C. Newman, ‘The sacral landscape of Tara, pp 35–6, this volume. 65 Macalister & Praeger,‘The excavation of Uisneach’, 93–4, 122–3, 126–7, and passim; Schot, ‘Uisneach Midi’, 50–4. 66 See, for

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 105

and it is very likely that the 200m ditched enclosure lying only a short distance toits north is also of significance in this context. Both monuments attest toUisneach’s role as a sanctuary, and it may well be the case that their constructionrelates to an intensification of ceremonial activity similar to that witnessed at other‘royal’ sites during the Iron Age. Indeed, when the archaeological evidence isconsidered against the backdrop of contemporary developments in the broaderlandscape, there are certainly strong indications that Uisneach had emerged as thepre-eminent ceremonial and religious centre in the region by this time.67

Whether Uisneach also functioned as a political centre in later prehistory ismore difficult to ascertain, not least due to the relatively limited scope of theavailable archaeological evidence and its openness to multiple interpretations. Agreater challenge, however, stems from the very nature of the socio-politicalstructures that existed in later prehistoric Ireland, and in particular the notableabsence of any clear-cut distinction between political and religious power. As iswell known, there is a vast and extensively documented body of evidence toindicate that early Irish kingship was essentially sacral in character and yet as aninstitution existed alongside a separate, mandarin caste of holy men and filid(‘seers’, ‘poets’ etc.) who, as Byrne notes, ‘in some ways … wielded more powerthan kings’.68 While there are no definitive criteria for distinguishing betweenthese various ‘sacred’ or ‘privileged’ (nemed) persons in the archaeological record,it is nevertheless intriguing to note how the later prehistoric monuments atUisneach are conspicuously lacking in the high visibility and ‘monumental’ aspectof the great earthwork enclosures at Tara, Emain and Dún Ailinne. This is of someinterest given that, unlike Tara and some of the other ancient royal sites, Uisneachis never identified as a pre-Christian royal centre and is only nominally associatedwith kingship in the early literature. Rather, the primary significance of Uisneachis suggested to derive from its central and liminal status, a place ‘betwixt andbetween’, associated with deities and, in particular, the druids – the mediatorsbetween the temporal and supernatural realms. In these and other respects,Uisneach is imbued with many of the attributes common to central sanctuaries onthe Continent. One such site, mentioned by Caesar and now thought to lie in the

example, B. Raftery, Pagan Celtic Ireland (1994), pp 210–13ff; C. Swift, ‘Pagan monuments and Christianlegal centres’ (1996), 3–7; C. Newman, ‘The making of a “royal site”’ (1998), 132–4; R. Ó Floinn,‘Freestone Hill’ (2000); E. Grogan, Rath of the Synods (2008), pp 85–91 and appendices; R.B. Warner,‘Clogher in late prehistory’ (2009). 67 Schot, ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’, i, 255–303. 68 Byrne, Irishkings, pp 13–27 at p.14. See also D.A. Binchy, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon kingship (1970); E. Bhreathnach,‘Temoria: caput Scotorum?’ (1996); B. Jaski, Early Irish kingship (2000), pp 57–88; Doherty, ‘Kingship inearly Ireland’. For a broader perspective, see, for example, A.M. Hocart, Kingship (1927, repr. 1969); idem,Kings and councillors (1970); D. Cannadine & S. Price (eds), Rituals of royalty (Cambridge, 1987); D.Quigley (ed.), The character of kingship (2005); and M. Lecomte-Tilouine, ‘Imperial snake and eternal fires’,

106 Roseanne Schot

vicinity of Chartres Cathedral (c.90km south-west of Paris),69 provides a poten -tially apt, and oft-cited, parallel for Uisneach. As Caesar states in his discussion ofthe status and role of druids in Gaulish society,70

The Druids officiate at the worship of the gods, regulate public and privatesacrifices, and give rulings on all religious questions … They act as judges inpractically all disputes, whether between tribes or between individuals; whenany crime is committed … or a dispute arises about an inheritance or aboundary, it is they who adjudicate the matter … On a fixed date in eachyear they hold a session in a consecrated spot in the country of the Carnutes,which is supposed to be the centre of Gaul. Those who are involved indisputes assemble here from all parts, and accept the Druids’ judgementsand awards.

Caesar’s reference to an annual assembly at the ‘centre’ of Gaul is clearlymatched by Uisneach’s identification in early sources as an assembly-site and as aplace where judgments are promulgated. The inter-tribal nature of the gatheringdescribed by Caesar and its location on consecrated ground (locus consecratus), isalso of interest, given that the status of Uisneach appears likewise to have hingedon the idea that it lay outside contemporary socio-political divisions. In thiscontext, parallels are also apparent with the far-famed oracle and sanctuary ofApollo at Delphi, the ‘navel’ of ancient Greece, whose reputation, as Coleemphatically states, ‘depended on its appearance of neutrality because Apollocould be trusted only if his sanctuary could appear to be free from the influenceof individual communities’.71 This concept of neutrality is especially intriguingwhen considered in light of the archaeological evidence from Uisneach. Indeed,compared with the grandiose, ‘royal’ enclosures of the other ceremonial complexes,the relatively inconspicuous character of the largest prehistoric monuments atUisneach seems to diminish their effectiveness as material expressions of earthlypower, and could very well reflect the ritual exclusivity and political ‘detachment’claimed for the site in the early literature. All things considered, the possibility thatUisneach was more a religious than a political centre in later prehistory, and onlylater emerged as a bona fide ‘royal site’, cannot be easily dismissed.

in this volume. 69 A. Ross, ‘Chartres’ (1979–80); idem, ‘Ritual and the druids’ (1995), p. 438. 70 S.A.Handford (trans.), Caesar, The conquest of Gaul (1982), p. 140, §13 (De Bello Gallico VI.13). 71 S.G.Cole, Landscapes, gender, and ritual space (2004), p. 75.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 107

THE MAKING OF A ROYAL CENTRE

Whatever its precise role in later prehistory, it is clear that by the sixth century AD

Uisneach had evolved into a cult centre of sufficient standing to mark it out as anauspicious base for a new order of aspirant kings. The evidence of renewedbuilding and a shift to domestic occupation in the wake of its appropriation as aroyal seat by the southern Uí Néill marks an important juncture in the history ofUisneach, yet occurs in tandem with the promotion in the early literature of‘antique’ traditions associated with the site. Far from diminishing the sacralimportance of Uisneach, therefore, the construction of the impressive conjoinedringfort of Rathnew and its network of associated settlements must be understoodin a context in which the ritual of kingship was rooted in a pagan past andlegitimacy was gained by harnessing the power and significances invested inancient places. As Mac Cana notes, early medieval kingship represents ‘a reflex, ora replica, of the sacral kingship … and even when Irish rulers owed their accessionmore to force of arms than to hereditary right, they were always careful tolegitimize their claim by reference to the primal myth and ritual of sovereignty’.72

At Uisneach, as at many other ceremonial centres that retained an importancein an increasingly Christian milieu, this seems to have been achieved by adeliberate, and often nuanced, blending of old and new. As a forerunner in theeffort to transform Uisneach from a pagan cult centre into a Christian seat ofkingship, it is by no means incidental that the sixth-century saint Áed mac Briccchose to establish his first church in Mide – the territory won from Leinster by hiskinsman, Fiachu mac Néill – directly at the foot of the hill. Áed, whose nameliterally means ‘fire’, also stands out as a significant figure in his own right; inhagiographical tradition he is endowed with miraculous healing powers and, asMcCone has pointed out, embodies many of the characteristics of a christianizedpagan fire deity.73 Not only does he seem to assimilate many of the qualities andtraditions associated with the ‘older’ gods at Uisneach – an unusually highproportion of whom are associated with fire/solar attributes, learning and healing74

– but as a saint of the border and a mediator between kings,75 Áed also appears topersonify certain aspects of Uisneach’s role as a unifying entity, a status that itmaintained well into the medieval period.76

72 P. Mac Cana, ‘Early Irish ideology’ (1985), p. 57. 73 McCone, Pagan past, pp 165–6, 190 at p.165.74 Schot, ‘Uisneach, Co. Westmeath’, i, 92–4. 75 Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp 445–6; MacShamhráin & Byrne, ‘Prosopography I’, pp 219–20; A. Connon, ‘Prosopography II’ (2005), p. 325. 76 In1141, for example, Uisneach was chosen as the location of a ‘peace conference’ between Toirdelbach UaConchobair, king of Ireland, and Murchad Ua Máel Sechlainn, king of Mide: AFM, ii, pp 1066–7. See alsocommentary on this event in E. Bhreathnach, ‘Transforming kingship and cult’, p. 141, this volume.

108 Roseanne Schot

When examining the literary sources composed between the seventh andeleventh centuries, moreover, we see the physical appropriation of Uisneachmatched by its retrospective ‘colonization’ with ancestral figures and the moreunpalatable, pagan associations of the site rendered impotent at source. In EchtraeChonlai, for instance, the druid of Conn Cétchathach (ancestor of the Connachta/Uí Néill) features as the loser of a spiritual contest with a Christian otherworldmaiden at Uisneach; while in dindshenchas, the druids of Ireland, havingcomplained of the stipend due to the ‘heir of the plain of Mide’ for the primevalfire lit by Mide, had their tongues cut out and buried on the hill. As theconservators of oral tradition, the power of pronouncement attributed to thedruids and filid was fundamental to their role as arbiters, augurs, poets andsatirists,77 and the implications of Mide cutting out their tongues – deprivingthem of speech – are readily apparent. Similarly, while Alwyn and Brinley Reesare no doubt correct in describing the lighting of the druidical fire at Uisneach as‘a ritual proclamation of ascendancy’,78 one cannot fail to decipher in thesymbolism attending this act a very thinly veiled statement on behalf of the ClannCholmáin king(s) of Mide; after all, in addition to the transformative andpurificatory properties normally associated with fire (and indeed water), in earlyIreland the lighting of fires was also directly connected with the taking possessionof territory (tellach).79

An equally astute, if perhaps more audacious, approach to the past is evidencedin the treatment of the ‘Cat Stone’ – Tírechán’s Petra Coithrigi, ‘Patrick’s Rock’.The naming of the stone by Tírechán and its cursing in the later version of thesaint’s visit to Uisneach contained in the Vita Tripartita clearly indicate a desireto christianize a focus of pagan worship, although, as Thomas Charles-Edwardshas noted, Patrick appears to have met with less success in his attempt to convertthe site’s resident dynasts.80 Charles Doherty mentions this stone, together withothers bearing the same name at Cashel and elsewhere, in the context of potentialinauguration places,81 and the fact that it serves as a backdrop for St Patrick’smeeting with Fiachu mac Néill and his kin at Uisneach certainly hints at aprospective role for this stone as a symbol of kingship. In Do Shuidigiud TellaichThemra, moreover, any unsavoury connotations still attaching to the stone onaccount of its pre-Christian origins were removed altogether on the pretence that

77 See, for example, P. Mac Cana, Celtic mythology (1970), pp 14–16; D. Ó hÓgáin, The sacred isle (1999),especially pp 69–97. 78 Rees & Rees, Celtic heritage, p. 157. 79 See ibid., pp 157–8; F. Kelly, A guide toearly Irish law (1988), pp 186–7. For further examples and discussion of the significance of fire in thiscontext, see the essays in this volume by Bhreathnach, ‘Transforming kingship and cult’, Slavin,‘Supernatural arts, the landscape and kingship’ and Ní Bhrolcháin, ‘Death-tales of the early kings ofTara’. 80 Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp 28–30; see also Doherty, ‘Kingship in early Ireland’,9–11. 81 Doherty, ‘Kingship in early Ireland’, pp 9–11.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 109

it was only erected in the mid-sixth century during the reign of Diarmait macCerbaill as king of Tara. As well as serving to legitimize Uí Néill claims toownership of the site, it is hardly insignificant that the judgment promulgated inthe tale regarding the cosmographical division of the island is said to have derivedfrom a precedent set by Tréfuilngid Tré-eochair, a mysterious figure described as‘[he] who cause[s] the rising of the sun and its setting’ and ‘an angel of God, or …God Himself ’.82

The death and burial at Uisneach of Lug – the archetypal, omniscient ‘king’ –is more overtly suggestive of the symbolism of sovereignty. Lug’s end is broughtabout by Mac Cuill, Mac Cécht and Mac Gréine, whose names identify them assons of ‘hazel’, ‘ploughshare’ and ‘sun’ respectively, the consorts of the triadicsovereignty goddess Fótla/Banba/Ériu.83 Before his death, moreover, Lug iswounded by a spear in one foot, an incident that could be interpreted as a varianton the motif of the ‘single shoe’ and, more specifically, corrguinecht, being one-legged.84 In early Irish mythology, the condition of being one-legged, or indeedone-armed or one-eyed, are attributes associated both with enhanced potency and,conversely, with the forfeiture of power, as any form of physical defect or blemishin a king was viewed as a violation of fír flathemon (‘prince’s truth’), leadinginevitably to the loss of his kingship. However the text is construed in this respect,it suggests that the burial mound (Carn Lugdach) said to have been raised in Lug’shonour – ostensibly that located next to Lough Lugh (Loch Lugborta) on thesummit of Uisneach – may have played a central role in royal ceremonies duringthe early medieval period. Not incidentally, the monument is clearly visible fromRathnew Enclosure, only a short distance to its south, and it is also worth bearingin mind that the massive ditched enclosure that has been shown to encircle themound would have had a greater topographical expression prior to the onset ofcultivation across much of the hilltop in recent centuries. The prominence of CarnLugdach within this discrete group of monuments raises the distinct possibilitythat it served as the inauguration mound of the kings of Uisneach – the finaldestination, perhaps, in a royal procession that also took in other significantmonuments such as the Cat Stone. Several other notable features located in thevicinity of the stone, including the magical spring of Tobernaslath/In Finnflescachand a recumbent stone slab lying on the summit of a low hillock adjacent to thespring, may also have had significance in this context. The slat element in theplace-name Tobernaslath, for instance, could very well be a reference to the ‘rod of

82 Best, ‘Settling of the manor of Tara’, 140–1, §15, 152–3, §31. 83 See, for example, LGÉ, iv, pp 130–1.In one version of the account on the coming of the sons of Míl, Ériu (or Fotla) is herself at Uisneach whenshe proclaims that the island would be theirs forever and in return for this ‘good prophesy’, requests thatthe island be named after her (ibid., pp 34–7, §392). 84 For a discussion of these motifs, see P. Mac Cana,‘The topos of the single sandal’ (1973); K. McCone, ‘The Cyclops’ (1996), 95–8; FitzPatrick, Royal

110 Roseanne Schot

5 (above) The Cat Stone – celebrated ‘navel’ of ancient Ireland.6 (below) Mound on the eastern summit of Uisneach, whose prominent location affords

extensive panoramic views across the central plain of Ireland.

kingship’ (slat na ríghe), the highly symbolic insignia of office in medieval king-making rites, in which recumbent stones (leaca) also figured prominently.85

As well as a possible venue for royal inauguration, there is an impressive bodyof evidence to support the identification of Uisneach as a place of assembly. Earlylegal texts are unambiguous in stating that every king (rí túath) was obliged tohold an assembly (óenach) at regular intervals; like inaugurations, these gatheringswere convened on ‘royal land’ (mruig ríg), which Fergus Kelly describes as ‘certainlands in each kingdom … set aside specifically for the use of the king during hisreign’.86 That the Hill of Uisneach was regarded as ‘royal land’ is perhaps implicitin the fact that the territorial losses incurred by Cenél Fiachach on ClannCholmáin’s rise to power appear to have been largely confined to this district.Other early literary sources also make clear that ancient cemeteries and ceremonialcomplexes formed the principal venues for royal assemblies, which wereundoubtedly funerary in origin.87 The presence of a large-scale enclosure aroundthe summit mound of Carn Lugdach suggests that the assemblies located atUisneach in the early literature could very well have originated in the religiousceremonies that took place there in later prehistory.

In many texts, Uisneach acts as a stage for large gatherings of people, some ofwhich are explicitly described as formal assemblies. Thus, in the tale Tucait BaileMongáin, a ‘great gathering’ at Uisneach provides the backdrop to the mythicalhailstorm that gave rise to Ireland’s chief streams, while in dindshenchas, Lug’sdeath is likewise depicted as having taken place during an assembly on the hill.Both of these texts use the term mór dál (‘great meeting’) to describe the assembly,a designation also used in Acallam na Senórach, which treats of Mordáil Uisnig (the‘Assembly of Uisnech’) as one of the three ‘noble meetings’ held in early Ireland,together with Óenach Tailten (the ‘Fair of Tailtiu’) and Feis Temro (the ‘Feast ofTara’).88 According to a tract on royal prohibitions and prescriptions, which, inits present form, appears to date from the eleventh century, the kings of Irelandwere obliged to purchase their ‘seats’ at the assembly of Uisneach, held once everyseven years:89

Séts after his place has been proclaimed (?)in Uisnech of mead-rich Meathin every seventh fair yearfrom him to the king of wholesome Uisnech.

inauguration, pp 122–9. 85 See FitzPatrick, Royal inauguration, especially pp 1–12, 99–122. 86 F. Kelly,Early Irish farming (2000), p. 403. 87 D.A. Binchy, ‘The fair of Tailtiu’ (1958), 124; Byrne, Irish kings, p.10. 88 Dooley & Roe, Tales of the elders of Ireland, p. 205; see also Binchy, ‘The fair of Tailtiu’. 89 M.Dillon (ed.), ‘Taboos of the kings of Ireland’, 22–3. On the date of this text, see E. Bhreathnach, Tara: a

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 111

The idea that Mordáil Uisnig was only celebrated on a septennial basis is notfound elsewhere; in fact, the majority of later (medieval) references to the assemblytreat it as an annual event, held during the festival of Beltaine at the start of May.90

Geoffrey Keating, who provides a short and highly speculative account of thisputative Beltaine assembly in his Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, describes it as ‘a generalmeeting of the men of Ireland’, held annually in honour of the god Bel, duringwhich ‘it was their custom to exchange with one another their goods, their waresand their valuables’.91 Far from portraying the fair solely as a commercial event,however, Keating also tells of sacrifices offered to Bel, which reputedly involveddriving cattle between two fires ‘to shield them from all diseases during that year’,a practice also described – although without specific reference to Uisneach – in amuch earlier text known as ‘Cormac’s Glossary’, dating to c.900.92

The apparent lateness and unreliability of the tradition that associates MordáilUisnig with the festival of Beltaine led Binchy to dismiss it outright as pseudo-historical invention, especially ‘as such an important and numerous gatheringwould surely, like the Fair of Tailtiu, have from time to time provoked incidentswhich the chroniclers would have deemed worthy of recording’.93 Binchy does,however, consider that the tradition is likely to stem from the religious importanceof Uisneach in prehistoric times, and in particular its association with a pagan fire-cult, which granted the site ‘an aura of ancient sanctity’ that survived well into themedieval period.94 While the lack of any historical references to an assemblyhaving taken place at Uisneach prior to the twelfth century might well be ofrelevance, it is worth recalling that apart from Óenach Tailten, the pre-eminentassembly in early Ireland presided over by the king of Tara at Lugnasad, suchevents are rarely mentioned in the early medieval annals.95

Nor should the veracity (or otherwise) of Uisneach’s role as an assembly placebe measured solely on the basis of early medieval historical records, as this is tooverlook other potentially significant strands of evidence. Indeed, in light of thearchaeological, early literary and place-name evidence outlined above, it is perhapsof no small consequence that the village of Loughnavalley, which lies directlyunder the shadow of the Hill of Uisneach to the east, was up until relatively recenttimes the location of an annual fair, held on 15 August.96 That this ‘fair’ mayrepresent a survival – or a revival – of a Lugnasad assembly held in the neighbour -hood of Uisneach in ancient times finds support in a much more widespreadpattern evidenced elsewhere in Ireland. Máire MacNeill, for instance, has

select bibliography (1995), p. 8. 90 See, for example, O’Grady, Silva Gadelica, ii, p. 77. 91 P.S. Dinneen(ed.), Foras feasa (1908–14), ii, pp 246–7. 92 Ibid. See also W. Stokes (ed.), Three Irish glossaries (1862),pp xxxv, 6; K. Meyer (ed.), Sanas Cormaic (1912), p. 12 93 Binchy, ‘The fair of Tailtiu’, 114. 94 Ibid.95 For a summary of the early historical references to óenaige, see Bhreathnach, ‘Transforming kingshipand cult’, this volume. 96 S. Lewis, A topographical dictionary (1837), p. 394.

112 Roseanne Schot

documented numerous annual fairs held in the immediate locales of ancientassembly places, often on a different but proximate date (the later fairs being heldalmost invariably on a Sunday), and suggests that the change of venue ‘may beexplained by the inconvenience for trading purposes of the original assembly-site,which was so often on a height’.97 Given the tenacity of the tradition thatidentifies Uisneach as an assembly-place, there seems little reason to doubt itsauthenticity; certainly, it would be difficult to conjure a more fitting location fora fair held in honour of Lug than the cemetery and ceremonial campus at whichhe is reputed to have been buried. The fact that such a Lugnasad gathering wouldhave clashed with the more prestigious Óenach Tailten – over which rulers of theUisneach dynasty of Clann Cholmáin, as kings of Tara, frequently presided98 –might go some way towards explaining the lack of historical references to anassembly at Uisneach during the early medieval period.

AcknowledgmentsThis essay stems from research and ideas developed over many years and hasbenefitted from the expertise of many colleagues and friends. I would especiallylike to thank my fellow editors, Conor Newman and Edel Bhreathnach, as well asGer Dowling, for their valued comments and discussions on various aspects of thispaper. Thanks are also due to Profs John Waddell and Steve Driscoll for theirhelpful insights and guidance, and to Professor Richard Bradley for kindly readingan earlier draft of this paper. I am grateful to Ger Dowling and Joe Fenwick forassistance in the field, and to David and Angela Clarke, and Kitty Fay andChristopher Fay, for facilitating the fieldwork on their lands. The research onwhich this paper is based was part-funded by a scholarship from the Irish ResearchCouncil for the Humanities and Social Sciences, and more recent survey atUisneach was generously supported by a grant from the Heritage Council.

97 M. MacNeill, Festival of Lughnasa (1962, repr. 2008), p. 287. 98 Quite apart from being over -shadowed by the ‘national’ assembly at Tailtiu, the practical difficulty posed by the prospect of the sameindividual being in two places at once was also recognized. The author of the dindshenchas account onSlemain Mide (townlands of Slanemore/Slanebeg, near Lough Owel, Co. Westmeath), for instance, seemsat pains to resolve the dilemma arising from the holding of two assemblies simultaneously at Samhain by theking of Mide/Ireland, one at Slemain and the other presumably at Tara or Tailtiu: see MD, iv, pp 296–9.

Monuments, myths and other revelations at Uisneach 113

Related Documents