This article was downloaded by: [Şafak Taktak] On: 12 May 2015, At: 17:04 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Click for updates Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tajf20 Evidence for an association between suicide and religion: a 33-year retrospective autopsy analysis of suicide by hanging during the month of Ramadan in Istanbul Safak Taktak a , Bahadir Kumral b , Ayla Unsal c , Taskin Ozdes d , Süheyla Aliustaoglu e , Yuksel Aydin Yazici e & Safa Celik e a Department of Psychiatry, Ahi Evran University, Training Hospital, Kirsehir, Turkey b Faculty of Medicine, Department of Forensic Medicine, Namık Kemal University, Tekirdag, Turkey c Department of Nursing, Ahi Evran University, Medical School, Kirsehir, Turkey d Faculty of Medicine, Department of Forensic Medicine, Abant Izzet Baysal University, Bolu, Turkey e Ministry of Justice, Council of Forensic Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey Published online: 12 May 2015. To cite this article: Safak Taktak, Bahadir Kumral, Ayla Unsal, Taskin Ozdes, Süheyla Aliustaoglu, Yuksel Aydin Yazici & Safa Celik (2015): Evidence for an association between suicide and religion: a 33-year retrospective autopsy analysis of suicide by hanging during the month of Ramadan in Istanbul, Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, DOI: 10.1080/00450618.2015.1034775 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2015.1034775 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

This article was downloaded by: [Şafak Taktak]On: 12 May 2015, At: 17:04Publisher: Taylor & FrancisInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Click for updates

Australian Journal of Forensic SciencesPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tajf20

Evidence for an association betweensuicide and religion: a 33-yearretrospective autopsy analysis ofsuicide by hanging during the month ofRamadan in IstanbulSafak Taktaka, Bahadir Kumralb, Ayla Unsalc, Taskin Ozdesd,Süheyla Aliustaoglue, Yuksel Aydin Yazicie & Safa Celike

a Department of Psychiatry, Ahi Evran University, TrainingHospital, Kirsehir, Turkeyb Faculty of Medicine, Department of Forensic Medicine, NamıkKemal University, Tekirdag, Turkeyc Department of Nursing, Ahi Evran University, Medical School,Kirsehir, Turkeyd Faculty of Medicine, Department of Forensic Medicine, AbantIzzet Baysal University, Bolu, Turkeye Ministry of Justice, Council of Forensic Medicine, Istanbul,TurkeyPublished online: 12 May 2015.

To cite this article: Safak Taktak, Bahadir Kumral, Ayla Unsal, Taskin Ozdes, Süheyla Aliustaoglu,Yuksel Aydin Yazici & Safa Celik (2015): Evidence for an association between suicide and religion:a 33-year retrospective autopsy analysis of suicide by hanging during the month of Ramadan inIstanbul, Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, DOI: 10.1080/00450618.2015.1034775

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2015.1034775

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

Evidence for an association between suicide and religion: a 33-yearretrospective autopsy analysis of suicide by hanging during the

month of Ramadan in Istanbul

Safak Taktaka, Bahadir Kumralb*, Ayla Unsalc, Taskin Ozdesd, Süheyla Aliustaoglue,Yuksel Aydin Yazicie and Safa Celike

aDepartment of Psychiatry, Ahi Evran University, Training Hospital, Kirsehir, Turkey; bFaculty ofMedicine, Department of Forensic Medicine, Namık Kemal University, Tekirdag, Turkey;

cDepartment of Nursing, Ahi Evran University, Medical School, Kirsehir, Turkey; dFaculty ofMedicine, Department of Forensic Medicine, Abant Izzet Baysal University, Bolu, Turkey;

eMinistry of Justice, Council of Forensic Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

(Received 10 November 2014; accepted 17 March 2015)

This study was undertaken to examine the effect of the Islamic holy month ofRamadan on the number of suicides in order to assess whether religious faith isassociated with a decreased number of suicides during that period. In this retrospec-tive study, a total number of 82,871 autopsies have been performed in the MorgueDepartment of the Council of Forensic Medicine (Istanbul) of the Ministry of Jus-tice between 1978 and 2012, 33 years. For the study purposes, the earlier start ofIslamic calendar months (i.e. 10 or 11 days earlier each year) compared with theGregorian calendar was taken into account and file details such as crime sceneinvestigation reports, information obtained from the police, and autopsy results wereassessed. Of the 4315 suicide cases, 267 were reported during Ramadan, while 4048were recorded during other months. Of the 33 years examined, only five Ramadanmonths exhibited a suicide rate above the annual average and there was a signifi-cantly lower (p = 0.042) incidence of suicides during Ramadan. Suicide by hangingis less frequent during Ramadan compared with non-Ramadan months, probablyreflecting a positive spiritual influence of this period on Muslims.

Keywords: forensic medicine; suicide; hanging; month of Ramadan

Introduction

Societal perception of suicide can significantly vary, and while suicide has not been anacceptable act in many societies throughout history, attitudes towards suicide – such ascondemnation, disapproval or approval – are largely determined by the cultural valuesand beliefs at specific times1.

Despite proposals regarding a lower number of unreported or undiagnosed suicidesin suicide-sensitive societies due to cultural, societal or familial effects, previous studieshave shown a lower rate of suicide among Muslim societies2–5.

While some studies examining the link between suicide and religious faith have foundinconsistent results6–8, a consensus exists as to a negative correlation between religiousfaith and suicide risk6,7,9,10. For instance, in a study by Ferrada-Noli Sundbom9 on adoles-cents, a negative association between suicide risk and religious faith was observed.

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

© 2015 Australian Academy of Forensic Sciences

Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 2015http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00450618.2015.1034775

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

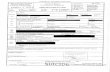

Figure 1. Suicide rates during Ramadan and non-Ramadan periods months years between 1979and 2011.

2 S. Taktak et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

Figure 1. (Continued)

Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

Religious people do not exhibit approval towards suicide and suicidal tendency11–13. Onthe other hand, atheists or people without strong religious convictions have been found tobe more tolerant to the idea of committing suicide, both for others and themselves12.

Ethnic origin may also play a role in the diversity of attitudes towards suicide, andlower rates of suicide have been reported in societies where suicide is strongly con-demned from a religious viewpoint. For example, Cirhinlioglu et al. found lower ratesof suicide among Muslims compared with Hindus14. In another study, by Yapıcı10,involving university students, a significant negative correlation was observed betweensuicide risk, the practice of praying and the ‘sensing the presence’ of a god. Other stud-ies in Muslim populations also showed negative associations between religious faithand suicide-related factors, such as suicidal plans, suicide attempts, and a wish to die15.

In a multi-national study involving 71 countries, Simpson and Conklin16 found nosignificant associations between the Christian faith and suicide rates, while a negativecorrelation between Islamic faith and suicide risk (0.55) was observed. This wasexplained on the basis of Islam’s stronger opposition to suicide and stronger social tiesarising from collective praying practices14.

The following verse from the Quran is a very clear prohibition of suicide: ‘Do not kill[or destroy] yourselves, for verily Allah has been to you most Merciful’ (Quran 4/29).

Great importance has been placed upon Ramadan and fasting in the Quran, as sev-eral of the following ayats (verses) clearly demonstrate: ‘O you who have believed,decreed upon you is fasting as it was decreed upon those before you that you maybecome righteous’ (Ayat 183); ‘The month of Ramadan [is that] in which was revealedthe Qur’an, a guidance for the people and clear proofs of guidance and criterion. Sowhoever sights [the new moon of] the month, let him fast it…’(Ayat 185). It is clearfrom the ayats that fasting – one of the ‘Five Pillars of Islam’ – involves abstinencefrom food, drink, and sexual intercourse from just before daybreak until sunset.

The word Ramadan derives from ramda, meaning ‘burning’. In that month, sins arebelieved to be burned by the fire of fasting. Also, some linguists maintain that the wordRamadan is derived from ramadiyu, meaning ‘the rain’, connoting purification bywashing. Therefore, Ramadan is thought to wash people from sins17. It is worth point-ing out that the Hadiths exempt several groups of people from fasting, including pre-pubescent children and the mentally ill.

Turkey is a constitutionally secular country, yet more than 99% of the populationare officially recorded as being Muslims4,18. Although the majority of Turks do notpractice the basic tenets of the religion, fasting during Ramadan is a popular religiousritual in which at least 70% of Muslims participate in one form or another.

Ramadan is a time when Muslims are expected to be calm and peaceful in daily lifeboth mentally and physiologically. Also, Islam considers suicide as a grave sin and thisconviction might play an important role in lower rates of suicide in Muslim societies18.Similarly, market research suggests alcohol sales and consumption decrease duringRamadan, which might also be associated with lower rates of crime involving alcohol-related violence.

Approximately half of all suicides in Turkey are by hanging, as shown by a numberof different studies for different time periods, i.e. the percentage of suicide by hangingcomprised 51.54%, 51%, 43.10%, 44.50%, 44.42%, 46.03%, 44.11%, 44.40%, 45.35%,47.44%, 49.43%, 53.73%, 52.10%, and 51.96% of all suicide cases in the years 1991,1992, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011,respectively. Similarly, 52.45% of all suicide cases were suicide by hanging in the year2011 in Istanbul19.

4 S. Taktak et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

Cases of suicide by hanging comprise most of the hangings in Turkey, while acci-dental hanging represents a minority of total cases and homicidal hangings are extre-mely rare20. The current study focused specifically on suicide by hanging alone due tofact that the great majority of the hanging cases, i.e. approximately 95%, are suicide-associated in Turkey21 and hanging as a means of suicide is a common, simple andeffective method to terminate one’s life.

Methods

Istanbul is the most populated city in Turkey, is culturally more diverse than the rest ofthe country and has the highest economic power. The city’s population in 1979 wasmore than 4.5 million (crude suicide rate of 1.76 per 100,000 persons). But by 2011,this population rose to more than 13.48 million. Turkey’s total population in 2011 was74,724,269, with a crude suicide rate of 3.62 per 100,000 persons.

In this retrospective study, a total of 82,871 autopsies have been performed in theMorgue Department of the Council of Forensic Medicine (Istanbul) of the Ministry ofJustice between 1978 and 2012, i.e. for 33 years. Ethical approval for the study wasgranted.

Of a total of 82,871 autopsy files, those younger than 15 years of age, those whowere uncircumcised (circumcision is another pillar of Islam and therefore a faith signi-fier), and those who were non-Turkish citizens were excluded.

All files were dated using the Gregorian calendar, thus requiring the determinationof Ramadan months for each Gregorian year. While Ramadan is the ninth month of theIslamic calendar each year, it involves a continuous change in terms of the dates of theGregorian calendar. The Muslim calendar is based on the lunar cycle of 354.367 daysand is therefore shorter than the Gregorian calendar by, on average, 10.8752 days.Ramadan also lasts for 29 or 30 days. Due to the difference between the two calendarsystems, a continuous forward shift of months take place, resulting in approximately33-year cycles before Ramadan resumes on the same Gregorian day. Therefore, in orderto eliminate the seasonal effect on suicide and to examine a relatively longer time-period, tables and graphs have been prepared to provide numeric comparisons betweenfasting and non-fasting periods.

To better delineate the association between Ramadan and non-Ramadan months andthe suicide rate, a separate graph was prepared for each year, whereby the vertical axisshows the number of suicides and the horizontal axis shows the months and years (Fig-ure 1). Each number denotes the number of suicides occurring during a certain month.Each straight line on the graph shows the annual average, while the mid line signifiesthe unified suicide rate and the anterior line signifies suicides occurring during Rama-dan only. Due to the absence of a normal distribution of the data, a non-parametricMann-Whitney U-test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 4315 cases of suicide by hanging were determined. Table 1 depicts the sui-cide rates for 33-successive Ramadan and non-Ramadan months from July 26, 1979,until August 1, 2011, along with the total number of suicides and monthly average sui-cide rates for a given year.

As can be seen from Table 1, there were actually a total of 34 Ramadan months dur-ing this 33-year period, as 1997 encompassed two Ramadan months in one Gregorian

Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

year. However, since our data are presented in accordance with the Gregorian calendar,the number of suicides during Ramadan months is shown in tables and Figure 1 graphsregardless of their occurrence time-wise in the Islamic calendar. For example, forRamadan starting on December 31, 1997, suicides occurring on the first day of Ramadanwere included in 1997 statistics, while suicides occurring thereafter until the last day ofRamadan month, i.e., January 21, 1998, were included in 1998 statistics. In 1997, 1998

Table 1. The first and last days of Ramadan months, suicide rates during Ramadan and non-Ramadan periods, and the total number of hanging suicides between 1979 and 2011. Annualaverage and the corresponding years.

Gregorianyear Starting date End date Ramadan

Non-Ramadan

TotalSuicidevictims

Averageannual

Lunaryear

1979 26 July 23 Aug. 1 17 18 1.5 13991980 13 July 11 Aug. 1 28 29 2.41 14001981 03 July 31 July 4 47 51 4.25 14011982 23 June 21 July 3 39 42 3.5 14021983 12 June 11 July 3 54 57 4.75 14031984 01 June 29 June 8 45 53 4.41 14041985 21 May 19 June 4 46 50 4.16 14051986 10 May 08 June 3 46 49 4.08 14061987 29 Apr. 28 May 3 47 50 4.16 14071988 18 Apr. 16 May 10 75 85 7.08 14081989 07 Apr. 5 May 5 58 63 5.25 14091990 28 Mar. 25 Apr. 4 50 54 4.5 14101991 17 Mar. 15 Apr. 4 51 55 4.58 14111992 06 Mar. 03 Apr. 4 74 78 6.5 14121993 23 Feb. 23 Mar. 4 82 86 7.16 14131994 12 Feb. 12 Mar. 2 114 116 9.66 14141995 01 Feb 02 Mar. 3 139 142 11.83 14151996 21 Jan. 19 Feb. 5 118 123 10.25 14161997 10 Jan.

(1997) 31Dec. (1997)

8 Feb(1997) 28Jan (1998)

7 152 159 13.25 1417–1418

1998 20 Dec. 18 Jan. 17 123 140 11.66 1418–1419

1999 09 Dec. 07 Jan 16 125 141 11.75 1419–1420

2000 27 Nov. 26 Dec. 15 141 156 13 1420–1421

2001 16 Nov. 15 Dec. 13 167 180 15 14222002 05 Nov. 04 Dec. 9 210 219 18.5 14232003 26 Oct. 24 Nov. 9 167 176 14.66 14242004 14 Oct. 12 Nov. 16 180 196 16.33 14252005 04 Oct. 02 Nov. 9 183 192 16 14262006 23 Sept. 22 Oct. 12 204 216 18 14272007 12 Sept. 11 Oct. 15 230 245 20.41 14282008 01 Sept. 29 Sept. 9 251 260 21.66 14292009 21 Aug. 19 Sept. 13 249 262 21.83 14302010 11 Aug. 08 Sept. 18 288 306 25.5 14312011 01 Aug. 29 Aug. 18 248 266 22.16 1432General

total267 4048 4315

6 S. Taktak et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

and 1999, Ramadan months extended into the succeeding year, resulting in a totalRamadan days of 31, 41, and 37 in years 1997, 1998, and 1999, respectively.

Of the 33 years examined, the suicide rate during Ramadan months exceeded theaverage suicide rates in other months only in 1984, 1988, 1998, 1999, and 2000. In1979 and 1980, a total of 47 suicides were recorded, while the corresponding figurewas 51 in 1981, with an increase in the number of suicides in the following years.May 8, 1997, (Gregorian calendar) corresponds to the start of the year 1418 accordingto the Islamic calendar (one year is equal to 354 or 355 days according to the Islamiccalendar).

It follows that during the Gregorian year of 1997, two Islamic years (i.e. 1417 and1418) were present and, similarly, until 2000, this overlap of Islamic years occurredfour times, revealing a total suicide number of 267 during Ramadan months and 4048during non-Ramadan months, with an overall suicide rate of 4315 in the 33-year period(Table 1).

In 1979, 1980 and 1981, an increase in suicides in the same months was observed,while there were only, respectively, one, one, and four suicides in Ramadan months. InMarch, September and November 1982, again an increase in suicide rates was observedthat halted by the start of the Ramadan and was followed by a September wave (sevencases) and pre-winter fluctuation. Then there were a total of three suicides in June(one) and July (two) during the Ramadan period, followed by four peaks in January,May, August, and December in 1983.

The average annual suicide rate in 1984 was 4.41 per month, with eight cases dur-ing the Ramadan month in the same year. In 1985, 1986 and 1987 there were four tofive peaks in the same years, with a below-average suicide rate during Ramadan. In1987, a winter wave with nine cases was followed by a decrease to three cases inRamadan. In April and May 1988, overlapping with the Ramadan period, there were10 suicides (one in April and nine in May), with 12 cases in the non-Ramadan days ofMay, with similar peaks in similar months in 1989–1997 and lower than average ratesduring Ramadan months.

During the Ramadan period, starting on 10 January 1997, and lasting for 30 days,and during the Ramadan period starting 31 December 1997, and ending on 28 January1998, the suicide rate was lower than the annual average, while the rate was above theaverage (17 cases) in Ramadan 1998, which lasted for 41 days. Similarly, there were16 suicide cases during Ramadan 1999, which lasted for 37 days with above-averagerates, and similarly an above-average suicide rate was detected in Ramadan 2000,which lasted only 30 days.

In 2001, suicide rates during Ramadan were slightly above the average. Between2002 and 2011, there was an increase in the number of suicides compared with previ-ous years, while suicide rates during Ramadan for the same period were below annualaverage with similar monthly fluctuations.

An analysis of the last three-year period shows that there were 24, 33, and 22 sui-cide cases in March, June, and October 2009, respectively, with five cases in Augustand eight cases in September overlapping with the Ramadan period.

In 2010 there were four peaks in January, March, June, and December, with 18cases during Ramadan (13 cases in August and five cases in September). In the sameyear, there were a total of 20 suicides in August including non-Ramadan days, and 21suicides in September. In 2011 there were 25, 27, 32, and 27 cases in March, May,July, and November, respectively with four peaks and 18 suicides in August overlap-ping with Ramadan.

Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

Due to the absence of a normal distribution of the current data, non-parametric testswere used for analyses. Comparison of Ramadan versus non-Ramadan months with theMann-Whitney U test in terms of suicide rates showed a statistically significant (p =0.042) difference (Table 2).

Discussion

This study was carried out to shed some light on the question of whether Ramadan hasany effect on suicide rates among Muslims living in Istanbul, i.e. the most populatedcity of Turkey, where 99% of the population officially belongs to the Islamic faith and70% of the population observes some ritual in the holy month of Ramadan.

The study population consisted of individuals committing suicide older than15 years of age (the age at which mental maturation is reached according to Muslimdoctrine) and males who are circumcised as a proof of obligatory religious practice.

In a study by Taktak et al.22 examining a population consisting of completed casesof suicide in Istanbul, information collected from family members suggested that91.9% of victims were religious despite the absence of routine religious practices, 6.5%worshipped regularly, while 1.6% demonstrated no religious faith at all.

In the present study, the suicide rate during Ramadan was above the annual averagein only five of the 33 years examined (1984, 1988, 1998, 1999 and 2000), with lowerrates in the remaining 28 years. The rise in the number of suicides in 1984 might havebeen indirectly related to the military coup in 1980, which had major social influences,or to the commonly reported increase in suicide rates during the summer months. Simi-larly, the increase in suicide rates in 1988 could have been related to the previouslyreported increase in the spring months of April and May23,24 or the summer months.

Indeed, several previous studies have suggested a substantial effect of seasons onsuicide rates25,26, consistent with findings reported at the national level in Turkey27,28.Above-average suicide rates during Ramadan in 1998, 1999 and 2000 (close to theaverage but slightly lower in 2001) might be associated with a higher number of Rama-dan days in these years. Normally, Ramadan lasts 29 or 30 days, although it lastedlonger in the above-mentioned years, resulting in increased numbers of suicides duringthese years. Another possible contributory factor is the fact that these years representthe era before 2001, when there was a major economic collapse in Turkey.

In a study by Asirdizer et al.29, socioeconomic factors were not found to have animpact on crude suicide rates in Turkey and this was explained on the basis of religiousfactors and close family ties. Meanwhile, Taktak et al.22 observed that 39.5% of suicidevictims had a lower income than their expenditure, suggesting that economic factorscannot be easily ruled out as a contributory factor.

Our graphs demonstrate that there were at least two peaks in suicide rates, thoughnot very substantial in spring and summer, and that there was also a peak before winterand lower rates during Ramadan each year. The initial years of the study period

Table 2. U-test for Ramadan and non-Ramadan hanging suicides.

n Mean rank Sum of ranks U p

Ramadan 33 28.70 947.00 386.00 0.042Non-Ramadan 33 38.30 1264.00

8 S. Taktak et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

involved lower numbers of suicides, hampering the demonstration of a seasonalassociation, after which this association became more evident, together with anincreased number of cases.

In the study by Demirci et al.18, involving 27 cases of suicide during Ramadan in a10-year period, a slight decrease was observed in Ramadan. In contrast, Cantürket al.30 examined the causes of death (natural, accidental, homicidal or suicidal) duringRamadan between 2003 and 2006 in two different cities and found an increased ratefrom 1988 until 1998. In Jordan, Daradkeh et al.31 examined the association betweenpara-suicidal behaviour and pre- and post-Ramadan periods, with significant decreasesduring Ramadan followed by a protective effect in the following months after Rama-dan. The seemingly conflicting results from these three studies might be related to alower number of cases or shorter study duration.

In the current study, encompassing 33 years and 34 Ramadan months, with a totalof 4315 suicide victims, a statistically significant difference in suicide rates was foundbetween Ramadan and non-Ramadan periods, although the difference was only slightlysignificant (p = 0.042) (Table 2). It is plausible to suggest that since suicide is consid-ered a sin in Islam, Muslims are probably less inclined to commit suicide during Rama-dan – a period when deeper religious spirituality is experienced.

Our study represents one of the largest studies to date, examining suicide rates in aMuslim population during the Ramadan period, precluding sound comparisons withsimilar data reported elsewhere.

Strength and limitations

The strengths of our study include its long duration and more statistical power todemonstrate seasonal effects and inclusion of annual Ramadan cycles focusing on apredominantly Muslim (99%) population in Turkey, where 95% of all hangings are sui-cide-related and half of all suicide cases are suicide by hanging.

Possible limitations include lower numbers of suicides in the initial years of ourstudy starting from 1979 and the possibility of a non-suicidal death in cases originallyreported as suicidal deaths (for example 5% of all hangings in Turkey are not suicide-related).

It should also be borne in mind that suicide might have been a concealed cause ofdeath in certain situations. Suicide is regarded as a grave sin and is mostly treated withminimal, if any, toleration by society and/or family members, leading to unreported orunclassified suicides, again somewhat limiting the value of our conclusions.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, holy periods defined by a certain religion can influence human behaviour.However, human perception regarding such periods is probably as important as thisinfluence. Therefore, our results suggest that a lower rate of suicide in Ramadanmonths compared with non-Ramadan months is probably due to the positive spiritualinfluence this holy period has on human behaviour in a sample Muslim population,together with the positive spiritual perception by the same population.

Further studies involving other sects of Islam or Muslims residing in other locationswith people from other religious faiths may shed more light on this issue, along withother studies examining the association between causes of death and suicide.

Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

AcknowledgementWe would like to thank Nilüfer Şahin Taktak for her kind support in data analysis of this work.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Disclosure statementNo potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References1. Sayar M. İntihar ve İnanç Sistemleri [Suicide and belief systems]. New symposium. 2002;

40(3):100–104.2. Khan MM. Suicide and attempted suicide in Pakistan. Crisis. 1998;19(4):172–176.3. Beautrais AL. Suicide in Asia. Crisis. 2006;27(2):55–57.4. Lester D. Suicide and Islam. Arch Suicide Res. 2006;10(1):77–97.5. Rezaeian M. Islam and suicide: a short personal communication. Omega (Westport). 2008–

2009; 58(1): 77-85.6. Stack S. The effect of religious commitment on suicide: a cross-national analysis. J Health

Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):362–374.7. Stark R, Doyle DP, Rushing JL. Beyond Durkheim: religion and suicide. J Sci Study Relig.

1983;22(2):120–131.8. Bainbridge WS. The religious ecology of deviance. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54(2):288–295.9. Ferrada-Noli M, Sundbom E. Cultural bias in suicidal behavior among refugees with posttrau-

matic stress disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 1996;50(3):185–191.10. Yapıcı A. Ruh sağlığı ve din: psiko-sosyal uyum ve dindarlık [Mental health and religion:

psycho-social harmony and religiousness]. Ankara: Karahan Kitabevi; 2007 (in Turkish).11. Ellison CG, Smith J. Toward an integrative measure of health and well being. Am J Psychol-

ogy and Theology. 1991;19(1):35–48.12. Minear JD, Brush LR. The correlations of attitudes toward suicide with death anxiety, reli-

giosity, and personal closeness. Omega (Westport). 1980;11(4):317–324.13. Stack S. Heavy metal, religiosity, and suicide acceptability. Suicide Life Threat Behav.

1998;28(4):388–394.14. Cirhinlioglu FG, Ok Ü. The relations between faith or worldview styles and attitude towards

suicide, depression and life satisfaction. C. Ü. Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 2010;34(1):1–8.15. Jahangir F, Rehman H, Jan T. Degree of religiosity and vulnerability to suicide attempt/plan

in depressive patients among Afghan refugees. Int J of Psychology of Religion. 1998;8(4):265–269.

16. Simpson ME, Conklin GH. Socioeconomic development, suicide and religion: a test of Dur-kheim’s theory of religion and suicide. Social Forces. 1989;67(4):945–964.

17. Gülendam Y. Dini bayramlarımız [Religious festivals]. Yeni Umit Dergisi. 2000;50(12):8–9.18. Demirci S, Dogan HK, Koc S. Evaluation of forensic deaths during the month of Ramadan

in Konya, Turkey, between 2000 and 2009. Am J Forensic Med and Pathol. 2013;34(3):267–270.

19. Suicide Statistics, Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK), 2011. Available from: http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/IcerikGetir.do?istab_id=23

20. Yılmaz R, Erkol Z, Bütün C, Beyaztaş FY, Ertan A, Büken B. A hanging case whose handswere tied. Türkiye Klinikleri J of Forensic Med. 2008;5(2):75–79.

21. Cantürk N, Cantürk G, Koç S, Özata AB. Deaths due to hanging in Istanbul; evaluation ofautopsies between 2000–2002. Turkish J of Forensic Med. 2005;19(1):6–13.

22. Taktak Ş, Üzün İ, Balcıoğlu İ. Determined of psychological autopsy of completed suicides inIstanbul. Anatolian J of Psychiatry. 2012;13(2):117–124.

23. Hiltunen L, Suominen K, Lonnqvist J, Partonen T. Relationship between daylength and sui-cide in Finland. J Circadian Rhythms. 2011;9(10):1–13.

10 S. Taktak et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

24. Kalediene R, Starkuviene S, Petrauskiene J. Seasonal patterns of suicides over the period ofsocio-economic transition in Lithuania. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(40):1–8.

25. Maes M, Cosyns P, Meltzer HY, De Meyer F, Peeters D. Seasonality in violent suicide butnot in nonviolent suicide or homicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(9):1380–1388.

26. Lester D. Seasonal variation in suicide and the methods used. Percept Mot Skills. 1999;89(1):160–160.

27. Asirdizer M, Yavuz MS, Demirag Aydin SA, Dizdar MG. Suicides in Turkey between 1996and 2005: general perspective. Am J Forensic Med and Pathol. 2010;31(2):138–145.

28. Erel Ö, Katkıcı U, Dirlik M, Özkök MS. The evaluation of the autopsied suicide cases at ourdepartment. Adnan Menderes Üniv Tıp Fak Dergisi. 2003;4(1):13–15.

29. Asirdizer M, Yavuz MS, Demirag SA, Tatlısumak E. Do regional risk factors affect the crudesuicidal mortality rates in Turkey. Turkish J of Forensic Med. 2009;23(1):1–10.

30. Cantürk N, Turkmen N, Cantürk G, Dagalp R. Differences in the number of autopsies andcauses of death between the months of Ramadan and control months and between two cities,Ankara and Bursa in Turkey. Medicinski Glasnik. 2013;10(2):354–358.

31. Daradkeh TK. Parasuicide during Ramadan in Jordan. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;86(3):253–254.

Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

afak

Tak

tak]

at 1

7:04

12

May

201

5

Related Documents