http://eep.sagepub.com/ Societies East European Politics & http://eep.sagepub.com/content/21/3/475 The online version of this article can be found at: DOI: 10.1177/0888325407303793 2007 21: 475 East European Politics and Societies Peter Vermeersch Poland A Minority at the Border: EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: American Council of Learned Societies can be found at: East European Politics & Societies Additional services and information for http://eep.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts: http://eep.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions: http://eep.sagep ub.com/content/21/3/475.refs.html Citations: What is This? - Aug 24, 2007 Version of Record >>

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 1/29

http://eep.sagepub.com/ Societies

East European Politics &

http://eep.sagepub.com/content/21/3/475The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0888325407303793 2007 21: 475East European Politics and Societies

Peter VermeerschPoland

A Minority at the Border: EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

American Council of Learned Societies

can be found at:East European Politics & Societies Additional services and information for

http://eep.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://eep.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://eep.sagepub.com/content/21/3/475.refs.htmlCitations:

What is This?

- Aug 24, 2007Version of Record>>

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 2/29

A Minority at the Border: EUEnlargement and the Ukrainian

Minority in PolandPeter Vermeersch*

This article examines the impact of the eastward enlargement of theEuropean Union (EU) on the position of the Ukrainian minority in Poland.The enlargement process has set two conflicting developments intomotion that both may have a serious influence on patterns of minority activism in countries at the peripheral borders of the enlarged EU. On onehand, there is a development toward increased protection of the externalborders of the EU. On the other hand, a new trend has become percepti-ble within the EU toward increased political, security, economic, and cul-tural cooperation with the new neighboring countries in the east. Applyingconcepts from research on social movements and using statements by Ukrainian minority activists as the basis for an empirical analysis, this arti-cle explores how these two opposite developments have affectedUkrainian minority activism in Poland.

Keywords: national minorities; EU enlargement; Ukrainian minority;Poland; ethnic mobilization

National minorities in countries at the peripheral borders of the

enlarged European Union (EU) find themselves in an intriguing

new situation. This is especially the case for minorities that now

have a neighboring non-EU country as their “external national

homeland.”1 The EU enlargement has set two conflicting devel-opments into motion that might have a profound impact upon

the position of these minorities. On one hand, there is the hard-

ening of the external borders of the EU (through, for example,

East European Politics and Societies, Vol. 21, No. 3, pages 475–502. ISSN 0888-3254© 2007 by the American Council of Learned Societies. All rights reserved.

DOI: 10.1177/0888325407303793

475

* An earlier version of this article was presented at the POLIS 2005 conference, Science Po,

Paris, 17 June 2005. This article is part of a larger study on the influence of international politi-

cal change on domestic minority-majority relations in Poland and other Central European

countries. In the framework of this project, I have studied Ukrainian minority activism in Poland

from various angles. This article focuses on the influence exerted by EU institutions. In another paper I have examined this case from the perspective of the changing interstate relationsbetween Poland and Ukraine: Peter Vermeersch, “National Minorities and International Change:

Being Ukrainian in Contemporary Poland” (manuscript, 2006).

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 3/29

the incorporation of the Schengen system into the EU and the

construction of an integrated European system of border man-

agement, a process in which the establishment of Frontex in

October 2005, the Warsaw-based EU agency that is tasked tocoordinate cooperation between the EU’s member states in the

field of border security,2 has been a crucial step). This develop-

ment is likely to render cross-border contacts between minority

populations at the borders of the EU and their ethnic kin in

neighboring non-EU countries more difficult. It may weaken the

position of minority groups; it may also galvanize group feeling

among minorities and majorities, stimulate thinking in ethnic

collectives, and hamper discussions between minorities andmajorities about how to resolve historical disagreements.

On the other hand, however, a new trend has become per-

ceptible within the EU toward increased political, security, eco-

nomic, and cultural cooperation with the new neighboring

countries in the east, made concrete most clearly in the

European Commission’s European Neighborhood Policy.3 This

latter development is explicitly meant to prevent the emergence

of dividing lines between EU members and their neighboringcountries. It may therefore, in theory at least, encourage initia-

tives for cross-border cooperation; it may cut across the tradi-

tional nationalist narratives in which ethnic actors typically frame

their demands, and create a context that facilitates reconciliation

between ethnic minorities and majorities.

The question is, what does EU enlargement mean for minor-

ity groups at the border of the enlarged EU? Do they see it as just

another phase in a complicated history of conflict, or as a realopportunity to raise a political voice, promote interests, and

lobby for change? This article examines this question for a par-

ticular minority group living in (or originating from) a historically

embattled cross-border region at the external border of the cur-

rent, enlarged EU. The small Ukrainian national minority in

Poland—which according to the last Polish census (2002)

numbers about thirty-one thousand people, which is less than

0.1 percent of the total Polish population, but which according toUkrainian minority activists numbers between two and three

hundred thousand people4 —is an informative case precisely

476 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 4/29

because Polish-Ukrainian relations have been marked by conflict

as well as cooperation. The collapse of communism has, on the

one side, highlighted the atmosphere of mutual recriminations

between Poles and Ukrainians related to the historical episodesof violence and displacement during and after the Second World

War. Yet since the early 1990s there have also been important

political forces in Poland who have actively pursued a strategic

partnership with Ukraine. Moreover, although current Polish-

Ukrainian relations within Poland have been characterized by

intense conflict over past injustices, on the elite level and in

international politics Poland and Ukraine were able to establish

good relations. This article asks how the accession of Poland tothe EU has affected Ukrainian minority activism in Poland.

The article contains five sections. The first offers a brief out-

line of a conceptual and theoretical framework derived from

research on social movements. The second section focuses on a

number of important and ongoing political and institutional

changes on the European level and shows that these changes

may, in theory, have a profound impact on the position of the

Ukrainian minority in Poland. The third section offers anoverview of the situation of the Ukrainian minority in Poland and

the development of Ukrainian minority activism since 1989. The

fourth section then goes on with an examination of the current

position of Ukrainian minority activism in the central govern-

mental institutions in Poland. This examination is partly based on

a content analysis of the documents produced by these govern-

mental bodies and the transcripts of the discussions in two com-

missions of the Polish lower house (Sejm) in the four yearsbefore the last parliamentary elections (September 2005). I will

conclude that while European integration has clearly been a

dominant structuring force when it comes to international diplo-

matic relations between Poland and Ukraine and the regulation

of cross-border contacts, so far it has had little impact on

processes of reconciliation between Poles and Ukrainians in

Poland. Ukrainian minority activism in Poland appears not to

have been able to benefit much from the firm Polish support for Ukraine in the EU context. The last section of the article provides

a number of possible explanations for this main finding.

East European Politics and Societies 477

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 5/29

Theoretical background: Minority activism and political opportunities

Why would one expect the position of the Ukrainian minority

in Poland to have been affected by the changing international

environment in Europe and, in particular, by Poland’s accession

to the EU? More generally, on what theoretical basis would one

argue that ethnic relations in the domestic arena may be signifi-

cantly affected by changes in international politics?

There are at least two broad fields of theoretical research that

give rise to making such assumptions. The first is a body of soci-

ological literature on the nature of minorities. Rogers Brubaker,

for example, has argued convincingly that national minorities

should not be seen as fixed entities, but rather as dynamic and

relational political “fields.”5 Brubaker and other sociologists have

pointed to the fact that being a minority is not simply a matter of

ethnic or national identity; it is the product of processes of iden-

tification and categorization in which political action plays an

important role. Leaders, activists, and politicians use the lan-

guage of national identity to mobilize people for specific identity

projects and thereby “evoke” minorities and majorities.

According to Brubaker, nationalism should be seen as the result

of a relationship between three dynamic and contested political

fields: national minorities, nationalizing states, and external

homelands. Seen in this way, ethnic relations are what results

from the ongoing interaction between at least three groups of

actors: minority activists, state actors, and actors who are related

to what is perceived as the “external homeland” of a minority

population. In other words, the experience of what it is to belong

to a minority is closely linked to the way in which political actors

domestically and in an international context employ the lan-

guage of national and ethnic identity. When important changes

occur in the fields of the nationalizing state or the external

homeland, it is likely that this will create changes within the field

of the national minority. Other authors have built on this model to

formulate hypotheses about the decisive influence of “external

lobby actors” in increasing the bargaining power of a minority in

478 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 6/29

the context of a dynamic interplay between the state and minor-

ity activists.6

The second relevant body of theoretical literature deals with

social movements and globalization. Social movement researchhas argued that changes in the political and institutional contexts

that surround a social movement will lead to changes in the way

such a movement acts. In other words, this literature claims that

movements—including ethnic movements—will be affected by

the political and institutional contexts (the “political opportunity

structure”) in which they operate. To seize opportunities, move-

ment leaders will adjust their collective action strategies. These

general contentions are at the heart of what has become knownas “political opportunity” and “political process” theories.7 Social

movements, these theories argue, are to a large extent shaped by

their interaction with the political opportunity structure that sur-

rounds them.8 Seeking to develop a broad pallet of theoretical

tools for the analysis of social movements, many scholars have

not restricted themselves to structural factors. They have also

identified mechanisms of influence related to political agency

and perception such as framing techniques.9

Students of globalization, in turn, have argued that political

opportunities are not strictly related to the domestic arena. An

increasing number of authors argue that social movements are

clearly affected by global processes (such as the growing power

of intergovernmental institutions and multinational corporations

and the increasingly global reach of the media). Activists have

pushed their action beyond state borders and have in these

global processes found new opportunities and resources for influencing both state and nonstate actors.10 Once largely

ignored by movement scholars, recent studies have built on the

political opportunity and process approaches to argue that

movement formation is in fact profoundly influenced by

transnational political opportunities.11 Following this insight,

one could hypothesize that the developments on the level of the

EU have created an important expansion of the transnational

political opportunity structure for ethnic mobilization, especially in new EU member states.

East European Politics and Societies 479

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 7/29

Empirical background: The potentialinfluence of EU enlargement on Ukrainianpolitical activism in Poland

If the above theoretical contentions correctly identify the

international context (external homelands and intergovernmen-

tal structures) as a crucial factor shaping domestic ethnic poli-

tics, one should certainly expect this factor to be influential in

the case of the Ukrainian minority in Poland. There are actually a

number of characteristics of the relationship between Poles and

Ukrainians in Poland that would lead one to expect the interna-

tional context to be particularly important in this case.

First of all, minority issues in new EU member states cannot be

seen as isolated from European discussions on minority rights.

When Poland after 1989 sought to “return to Europe,” the coun-

try exposed itself to Europe-wide political discourses on the

importance of minority protection standards. In the beginning of

the 1990s, international organizations in Europe gave increasing

legitimacy to norms on minority protection and began monitor-

ing minority protection in individual democratizing states such

as Poland. One would expect minority activists in democratizing

countries to have been able to rely on these norms to buttress

their political action. Social movement scholars today increas-

ingly argue that movements may more easily than in the past

“amplify” their demands in the domestic arena by relying on the

monitoring activities of international organizations.12 This has

certainly been true in the field of ethnic relations in Europe.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, transnational social move-

ments promoting minority rights have managed to gain a certain

amount of influence on the normative agenda of European inter-

national organizations. These international organizations, in

turn, have increasingly become active participants in the shaping

of legal developments and policies toward minorities in domes-

tic arenas. This has been particularly clear in Central and Eastern

Europe. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in

Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, and the EU have all

applied various techniques (from soft “normative pressure” to

hard “membership conditionality”) to pressure the countries in

480 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 8/29

this region to change domestic state behavior toward minorities

and prevent ethnic conflict.13

Especially the technique of membership conditionality—seeing

minority protection as a precondition for membership—significantly increased the EU’s power in the countries of Central Europe.

Although traditionally not a part of the European integration

agenda, minority protection thus became a central rhetorical ele-

ment in the EU’s strategy for eastward enlargement. In the

course of the 1990s, the EU member states gradually committed

themselves to the principles of human rights protection and

antidiscrimination, most notably through the Maastricht and

Amsterdam Treaties, but the EU’s concern for minority protec-tion in the neighboring countries in Central and Eastern Europe

was clearly much more pronounced than its internal commit-

ment. Already in the beginning of the decade the desire to con-

tain or prevent ethnic conflict became part and parcel of the EU’s

external relations toward the candidate countries in Central

Europe. This was, of course, to a great extent the result of the

EU’s earlier inability to prevent and respond to the acute out-

break of violence in the Balkans and its subsequent fear for theemergence of similar conflict scenarios in other former commu-

nist countries. The EU sharply accentuated the role of minority

protection in the Copenhagen criteria for accession, hoping that

by so doing it would be able to maintain political stability

throughout the future territory of the union, especially in areas

where ethnic relations were volatile. Although the EU was some-

times accused of using a double standard, it is reasonable to

assume that this strategy did change the situation of minority activists in candidate member states. It is also reasonable to

assume that it had its influence in areas where there was no

immediate danger for a large-scale international conflict involv-

ing minorities, such as the eastern border zones in Poland.

Furthermore, one would expect the situation of the Ukrainians

in Poland to have been affected not only by the processes that

led to Poland’s accession to the EU but also by the more recent

policies of the enlarged EU toward the east. Among these arethose policies that were put into place with the purpose of either

hardening or softening the external border of the EU. A prime

East European Politics and Societies 481

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 9/29

example of the latter is the European Neighborhood Policy

(ENP). The ENP should be seen as part of the European

Commission’s attempt to create alternatives to further enlarge-

ment to the east. The ENP seeks to establish closer relations withthe countries bordering the enlarged EU as an alternative to EU

membership. But there is a certain level of ambiguity when it

comes to the “real” driving force of the program. In one of the

key speeches leading up to the introduction of the ENP in 2002,

Romano Prodi—at that time the president of the Commission—

referred to the need to put limits to the expansion of the EU:

We cannot go on enlarging forever. We cannot water down theEuropean political project and turn the European Union into just afree trade area on a continental scale. We need a debate in Europe todecide where the limits of Europe lie and prevent these limits beingdetermined by others. We also have to admit that currently we couldnot convince our citizens of the need to extent the EU’s borders stillfurther east.14

Later on, however, when elaborating the ENP into a more

detailed plan, the Commission tried to divert attention away

from the issue of the limits of enlargement as the main reason todevelop the ENP and began to put emphasis on the issue of

cooperation with the new neighbors as being at the heart of the

program. Yet the ambiguity remained. In February 2005, the

commissioner responsible for the ENP, Benita Ferrero-Waldner,

published an article in which she sought to highlight the impor-

tance of the ENP for Ukraine. “Let’s be clear,” she wrote, “this is

a plan to bring Ukraine closer to Europe, not to hold it in any way

at arm’s length.”15 Ferrero-Waldner’s defensive response to criti-cism reveals that the ENP has indeed been perceived by some

observers as a program that is ultimately more about establishing

frontiers than about creating good neighborly relations. EU ini-

tiatives aimed at stimulating cross-border regional development

(see, e.g., local cross-border initiatives, such as the Bug and

Carpathian “Euroregions” at the Polish-Ukrainian border) have

not been able to change that impression much because they

have been rather vague or have been lacking sufficient financialsupport.16

482 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 10/29

In other words, although it might still be true that “EU bor-

der’s policies are in flux, caught between forging links across

external borders and policing it,”17 in border countries such as

Poland, policing appears to become the EU’s more importantconcern. There are a number of reasons for this. First of all, new

EU initiatives in the field of justice and home affairs concerned

with the development of an integrated management system for

the external borders are to a large extent driven by the view that

Central Europe is a potential “buffer zone” against illegal immi-

gration.18 As the country with the largest share of the EU’s exter-

nal border, Poland is seen by the EU as one of the crucial

partners in the fight against illegal immigration. Second, sincethe incorporation of the Schengen acquis into the EU frame-

work, Poland has had to adopt new regulations in the field of

border protection. This has clearly affected Polish-Ukrainian rela-

tions. Even before becoming a member of the EU Poland had to

introduce a visa regime for Ukrainian citizens in accordance with

the Schengen requirements.19 As a result, there was a marked

decrease in the number of border crossings.20 It is not unlikely

that this will have an impact on local economic development inthe coming years (for instance, on small-scale trade between

Ukraine and Poland) but also, more generally, on the way in

which people in border areas perceive and construct the history

of the relationship between Ukrainians and Poles. As O’Dowd

and Wilson have formulated it, borders are “reminders of the

past.”21 Any transformation of borders means engaging with the

past.

In sum, what is important about the current policies of theenlarged EU toward the east is that they contribute to a recent

history of international measures and developments structuring

and influencing relations between countries and populations.

The relations between Poles and Ukrainians are a case in point.

Ever since the breakdown of the Soviet Union, diplomatic rela-

tions between Poland and Ukraine have been governed by

changes in the wider international context. Following the analy-

sis made by Kataryna and Roman Wolczuk, one may distinguishthree periods from 1991 to 2004.22 In the first, between 1991 and

1994, Poland’s foreign policy was driven by the country’s will to

East European Politics and Societies 483

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 11/29

improve its prospects of joining NATO. In this context, there was

little time and effort devoted to improve economic and political

cooperation with Ukraine, although Poland kept being support-

ive of Ukrainian independence. From 1994 onwards, after thepresidential elections in Ukraine and Poland, Poland put its coop-

eration with Ukraine more and more at the heart of its eastern

policy. What followed was a brief period during which both

countries stepped up their political, economic, and military

cooperation efforts. Polish policy in this period was mainly dri-

ven by a concern to avoid a far-reaching Russian influence at its

eastern borders. After 1998, the relations deteriorated again,

mainly as a result of Poland’s preoccupation with joining the EUand the EU’s apparent lack of interest in Ukraine.

In more recent times, Poland has again been able to improve

relations by actively supporting Ukraine’s bid to become a can-

didate for EU membership and has lobbied for a flexible visa

regime for Ukraine.23 Poland repeatedly took a pro-Ukraine

stance in its dealing with the EU. While Poland was obliged to

introduce a visa regime for Ukrainian citizens as a result of its

accession negotiations with the EU,24

it still managed to makeUkraine a priority in the ENP and stimulated the creation of a

European action plan specifically directed toward Ukraine.

Poland could furthermore evidence its willingness to support

Ukraine’s “return to Europe” by playing a crucial role in the

“Orange Revolution.” When in November 2004 the Ukrainian

election results sparked off widespread popular protest, Polish

political leaders (most significantly President Kwasniewski) and

activists from the former Solidarnosc movement could success-fully win the sympathy of the crowds of protesters in Kyiv. They

also sat down at the negotiation table forging the deal that would

lead to a repeat of the second round of the elections. Poland

found itself in a strong position as an ally of the Ukrainian popu-

lar movement for democracy and received simultaneously strong

backing from the EU, which had been particularly sharp in its

official denunciation of the large-scale electoral fraud that had

marred the first election results. One aspect of this episode that was not discussed widely in international press reporting about

the Orange Revolution was the wave of sympathy that protesters

484 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 12/29

in Kyiv were able to create in Poland. Although some of it may

have been guided by Polish popular nostalgia for a time of unity

in opposition against undemocratic leaders and a common fear

of new threats to democracy coming from Russia, it may never-theless have signaled the preparedness of Poles to construct

more positive ideas about Ukraine and Ukrainians. When, in

April 2007, a decree by Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko to

disband the parliament and call new elections caused a huge

conflict with Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, again Polish

leaders, most prominently President Lech Kaczynski, made clear

that they were prepared to assume the role of mediator.25

Whether these and other developments will indeed lead to theemergence of more positive ideas about the presence of Polish cit-

izens of Ukrainian descent in Poland is of course a question that is

difficult to answer today. But the international circumstances that

could lead to changing ideas are at least in place. One can observe

that the international context has created a context that may, in

theory, influence significantly the arena of domestic relations

between Ukrainian minority activists and Polish politicians. It has

been argued that Poland’s EU membership has added another layer of complexity to Polish-Ukrainian relations because it has affected

the “strategic relations” between Warsaw and Kyiv to an even

greater extent than Poland’s joining NATO in 1999.26 This complex-

ity must no doubt have been recognized by Ukrainian minority

activists in Poland, and could have led them to rely increasingly on

the international context and EU-related arguments to buttress

their domestic claims. At least that is what one expects. On the face

of it, the discursive dimension of European enlargement appears tooffer minority activists a powerful tool for altering contemporary

social memories of Polish-Ukrainian relations in Poland. One would

thus expect to see Ukrainian minority activists attach crucial impor-

tance to the process of Poland joining the EU to construct a collec-

tive action frame that helps to mobilize the Ukrainian minority,

render their activism more powerful, and push the Polish govern-

ment to adopt important policy changes. Has this indeed been the

case? The remainder of this article will explore Ukrainian minority activism in Poland more in detail to find out how the matter has

been perceived from the perspective of the activists.

East European Politics and Societies 485

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 13/29

Ukrainian minority activismin Poland: A brief overview

Ukrainian minority activism in Poland cannot be understood

without seeing it against the backdrop of the complex history of

the area that now forms the eastern part of Poland. The current

borderland region between Poland and Ukraine was for a long

time a peripheral area that remained unaffected by central

attempts at nation- and state-building and was marked by the

dominating presence of hybrid identities. Following the work of

the German anthropologist Georg Elwert, Chris Hann has used

the term “polytacticity” to characterize the local political and

social relations in this area at the end of the nineteenth century.

Hann defines polytacticity as the situation in which the “lumpy

features that we nowadays refer to as ‘ethnic groups’ or ‘cultures’

did exist, but not as sharply bounded units asserting exclusive

rights over territory. Identities cross-cut each other, and different

ties and allegiances were activated in different contexts.”27 In the

twentieth century, however, the Ukrainian and the Polish nations

gradually but forcefully became the dominant foci for social and

political identification in this region.

Some of the most crucial events in this history of national

community formation were related to the First and the Second

World Wars and their aftermaths. After the First World War, when

Poland was put on the map after more than a century of nonex-

istence, claims for dominance in the regions of eastern Galicia

and Volhynia caused tensions and fighting between those who

identified themselves as Ukrainians and those who considered

themselves to be Poles.28 In the period between the wars, Poland

introduced stringent assimilation policies toward the Ukrainian

population in its eastern provinces, which, in turn, allowed the

paramilitary forces of the Ukrainian national movement to build

up their mobilizing potential in these regions. In the beginning

of the 1930s, complaints were laid at the League of Nations, and

Western states severely criticized the Polish authorities for

oppressing about three million Ukrainians and by so doing cre-

ating receptive ground for Russian influence in the region.29

During the Second World War, a civil war between Poles and

486 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 14/29

Ukrainians broke out during which the military wing of the

Organization of Ukrainian nationalists (OUN), the Ukrainian

Insurgent Army (UPA), engaged in violent ethnic cleansing cam-

paigns directed against Polish communities. Large numbers of Poles were killed and, in return, a large number of Ukrainians

died as victims of reprisals by the Polish resistance army (AK).30

When in 1944 the borders of the new Polish state were estab-

lished, the Polish National Liberation Committee (PKWN) agreed

with the government of Soviet Ukraine to initiate a large-scale

population exchange operation. According to some sources,

482,000 people were relocated from Poland to Ukraine in the

period from September 1944 to June 1946.31

In 1947, a large-scale forced resettlement operation was organized, replacing

approximately 140,000 people identified as Ukrainians to the

north and the west of Poland (Ackja WisÂa “Operation Vistula”). The

basic idea underpinning these initiatives was to obliterate sup-

port for the UPA in the eastern regions. In practice, the primary

objective soon turned out to be the assimilation of Ukrainians

and the elimination of Ukrainian identity in the Polish eastern

regions by dispersing Ukrainians among Poles in the rest of thecountry.32

This history left a clear imprint on the way in which Ukrainian-

Polish relations were experienced during the post–World War II

period. In this period, particular events (especially the events

related to the civil war, the establishment of the border, and the

resettlement campaigns) were becoming important elements in

the formation of specific, distinctive national narratives among

Poles and Ukrainians in which each portrayed the other nation asresponsible for creating injustices and initiating violent conflict.

While the official Polish view on the past cultivated the image of

the Ukrainians as enemies, Ukrainian minority communities tried

to benefit from Poland’s formally proclaimed friendship with all

the nations of the Soviet Union to demand the freedom to

develop Ukrainian culture, organize education in the Ukrainian

language, conduct religious services, and return to the eastern

regions of Poland.33

Between 1958 and 1968, a part of the earlier replaced people did indeed return to the southeastern part of

Poland. Moreover, a Ukrainian cultural organization was allowed

East European Politics and Societies 487

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 15/29

to be established, and a number of Ukrainian magazines and

schools were founded. After 1968, however, during the last two

years under party leader Gomu lÂka and later during the period

under Gierek, minority policy again became much more restric-tive and opportunities for organizing the Ukrainian community

in Poland diminished.

By the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s,

Ukrainian activism found support from the growing opposition

movement in Poland and from Polish Diaspora publications in

the West, not in the least the Paris-based journal Kultura. The

intellectuals associated with Kultura promoted the idea of

friendship with an (increasingly) independent (and later also—asthey hoped—a more democratic) Ukraine as an ideal way of pro-

tecting Poland from the Russian sphere of influence. To win such

independence in the long term, they argued, short-term Polish

claims for revision of the border and the annexation of Ukrainian

territory needed to be abandoned, and instead a process of rec-

onciliation was to be started.

During the 1980s, Ukrainian activism remained at the margins

of the opposition movement mainly because of the rigid assimi-lation policy that marked this period, but also because the events

surrounding Solidarnosc absorbed nearly all of the opposition’s

energy. Yet the fact that independent intellectuals and dissident

thinkers had given so much attention to the case of the

Ukrainian minority in the early 1980s turned out to make matters

easier for Ukrainian minority activists when it came to publiciz-

ing their cause at the end of the 1980s. Many people remem-

bered the arguments of the intellectuals linked to Kultura, andin the run-up to the round-table negotiations ending Communist

Party rule in Poland, a number of minority activists—among

them three Ukrainian activists (Micha ñesiów, W Âodzimierz

Mokry, and Stefan Kozak)—directed an appeal to Lech WaÂe[sa

demanding that a more generous approach to national minori-

ties be discussed at the roundtable talks. The Committee for

Cooperation with the National Minorities (Komisja WspóÂpracy z

Mniejszosciami Narodowymi) that was subsequently established within Solidarnosc brought intellectuals such as Jacek Kuron and

Bohdan Skaradzinski together with minority representatives

488 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 16/29

such as the Ukrainian activist W Âodzimierz Mokry. Soon there-

after Mokry was given a favorable place on the list of Solidarnosc

at the first parliamentary elections. From 1989 to 1991, he was

the first Ukrainian minority activist to have a seat in the Polishlower house (Sejm).34 Thanks to the work of mainly Kuron and

Mokry, a special committee dealing with national minorities was

established in the Sejm, and work on new legislative initiatives

was started.

Within this committee, minority activists initiated discussions

regarding such matters as minority language education, minority

representation in Parliament, and protection of cultural heritage

and religion; but when it came to the “Ukrainian issue” priority was given to the question of how, after so many years, the injus-

tices resulting from Operation Vistula could be redressed. In

other words, the usual minority demands, that is, demands for

the protection of culture, language, and territory and measures

leading to preferential access to political resources through, for

example, guaranteed representation, turned out to be not at the

heart of Ukrainian activism. When such “typical” minority

demands were made, they were always framed as subordinate todemands about redressing past injustices. The reason was

straightforward: Activists sought to initiate a debate about the

past, because they feared that if the complex history of forced

resettlement would not be taken into account in the formation

of minority policy, Ukrainians would not even be able to benefit

from any new minority legislation. In February 1989, for example,

the Ukrainian Socio-cultural Society (Ukrainskie Towarzystwo

SpoÂeczno-Kulturalne) published a report in which it argued that“because of the significant spread of the Ukrainian national

minority there is not a single electoral district where there is

even the slightest possibility of getting elected representatives,

whatever the number of votes may be.”35

In 1990, the Polish upper chamber (Senat) did indeed con-

demn Operation Vistula, an initiative that was first welcomed by

Ukrainian activists but later also criticized because of the con-

spicuous lack of concrete proposals for compensatory mea-sures.36 The more important condemnation from the Sejm,

however, did not follow. And it took more than a decade before

East European Politics and Societies 489

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 17/29

the Polish president would express his regret over this historical

episode. On the occasion of the fifty-fifth anniversary of the

events, Kwasniewski called Operation Vistula “a symbol of the

abominable deeds perpetrated by the Communist authoritiesagainst Polish citizens of Ukrainian origin.”37 What is important

here is that this condemnation was expressed in a period during

which Polish elites stepped up their efforts to establish good rela-

tions with Ukraine. From 1994 onwards, after the election of

Kuchma as the president of Ukraine, Poland and Ukraine engaged

in bilateral agreements. Strikingly, however, in these agreements

there was little or no room for declarations regarding the protec-

tion of minority rights. Kwasniewski may have seen his speech aspart of an effort to conciliate political leaders in Ukraine, but this

kind of connection was not made explicit. In other words, while

the issue of a partnership with Ukraine gradually became an

important element of international politics and was associated

with Poland’s economic and geopolitical interests, it was not

actively brought into connection with domestic issues.

This corresponds with dominant views in Polish society. Many

people continued to see the Ukrainian question mainly in the con-text of the domestic animosity of the past and not in the context

of improving relations between Poland and Ukraine. The domi-

nant view of the Ukrainians in Poland not only remained colored

by stories about Polish-Ukrainian antagonisms during and after the

Second World War; the image of the Ukrainians in Poland was also

increasingly affected by Polish popular fear of illegal immigration

and crime from the east. Polish sociologists have pointed out that

the general Polish perception of immigrant workers from Ukrainehas been complex. Although in practice Ukrainians have often

been regarded as good workers, they are also often associated

with illegal trade and the black economy.38

In sum, a striking aspect of the situation of the Ukrainian

minority in Poland is that there is a large discrepancy between the

dominant negative images of Ukraine and the Ukrainian minority

in Polish society and the positive way in which important

members of the Polish political elite and the civil society haveacted toward Ukraine. Given this state of affairs, Ukrainian minor-

ity activists in Poland have not had an easy time communicating

490 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 18/29

their concerns to the state and to the larger public. Did the

enlargement of the EU offer a point of support for Ukrainian

minority activism?

Domestic minority activism in an EUcontext: Exploring the “Ukrainian question”in Polish legislative and policy-making debates

To gain a better understanding of how the political strategies

of the Ukrainian minority activists have played out in the field of

Polish politics, it is useful to focus on the official institutional

forums in which minority activists have acted. When minority activists search for rights and recognition at the national level,

they have to make their claims heard within an official institu-

tional environment consisting of a number of relatively stable

elements in the political system, such as the parliament, the min-

istries, the various government administration units, the extant

governmental bodies, and so on. By analyzing the reports pro-

duced by these institutions in Poland and exploring the ways in

which these reports mention Ukraine and the Ukrainians, onemay gain a better idea of how successful Ukrainian minority

activists have been in attracting attention to their case at the

highest political level, and to what extent they have relied on the

ongoing international developments, such as the enlargement of

the EU, to attract attention to their case.

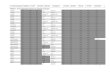

With this task in mind, I perused three bodies of sources: (1)

the documents produced by the bodies of the Polish govern-

ment responsible for minority affairs in the period between 2001and 2005, (2) the transcripts of the debates in the Sejm commis-

sion on ethnic and national minorities during the drafting of the

Polish minority law (adopted by the Sejm in January 2005), and

(3) the transcripts of the Sejm commission dealing with EU

matters in the run-up to the accession of Poland to the EU. I will

discuss these bodies of sources in turn.39

To begin, a few words are needed about the Polish govern-

mental bodies responsible for minority affairs. In 1997, anInterdepartmental Group for National Minority Issues was estab-

lished within the government administration (Miec dzyresortowy

East European Politics and Societies 491

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 19/29

zespó do spraw mniejszosci narodowych, hereafter “Interdepart-

mental Group”). Later, the government founded the Division of

National Minorities (Wydzia mniejszosci narodowych) at the

Ministry of Interior and Administration (2000). The first body gathered the representatives of various governmental depart-

ments. Although it did not include minority representatives, it

organized dialogues and information sessions with prominent

activists and representatives of officially recognized minority

organizations. The Division of National Minorities, on the other

hand, was a purely ministerial body aimed at raising the govern-

ment’s activities in the field of minority protection without open-

ing the official meetings up to minority activists. In January 2005,a new law on national and ethnic minorities and regional lan-

guage was officially published, a fact that led to the establishment

of a new governmental institution, the Joint Commission of the

Government and the National and Ethnic Minorities (Komisja

WspóÂna Rza[du i Mniejszosci Narodowych i Etnicznych), which is

meant to function as an advisory body to the government coun-

cil and includes minority representatives.40

The reports of the Interdepartmental Group show that in theperiod between 2001 and 2005 the Ukrainian minority was dis-

cussed mainly in the context of the following issues: the demand

for financing a Ukrainian cultural center, minority education,

access to public media, the restitution of property that once

belonged to Ukrainian organizations, and the setting up of a

monument in the labor camp site in Jaworzno (a former Nazi

concentration camp that from 1947 to 1949 was used by the

Polish authorities as a detention camp for Ukrainians suspectedof cooperation with the UPA).

During the 9th and the 10th session of the Interdepartmental

Group (April and June 2000), the importance of European devel-

opments was highlighted, but the focus was clearly on the issue

of how the government’s administrative bodies should help

Poland comply with European norms and standards (mainly the

Council of Europe’s Framework Convention on the Protection of

National Minorities), and not on the political consequences of EU membership for Poland’s relations with its immediate Eastern

neighbors. The EU was also a topic of discussion in the 16th

492 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 20/29

session (May 2001), when the participants in the meeting noted

that Poland was one of the few candidate countries that had not

made any use yet of EU funding for minority programs. Some

members of the commission placed blame on the minority activists themselves who were claimed not to be interested in

these European programs or lacked the expertise to submit suc-

cessful proposals. In 2002, the EU accession process was men-

tioned as an important context stimulating the government to step

up efforts to prevent discrimination. The Interdepartmental

Group discussed, for example, the need to comply with the legal

requirements set forth by the EU’s Directive 2000/43/EC of 29 June

2000 implementing the principle of equal treatment between per-sons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin. In 2003, European inte-

gration was discussed a number of times by the Interdepartmental

Group, but no direct links were made to the position of the

Ukrainian minority. Emphasis was again on the consequences of

complying with European legal standards such as the European

Charter for Regional and Minority Languages. As far as concrete

policy developments were concerned, the Interdepartmental

Group focused mainly on the issue of the Roma.One important conclusion that can be drawn from the reports

of the meetings of the Interdepartmental Group is that Ukrainian

minority activists had apparently not utilized—or at least had not

been able to utilize successfully—references to Poland’s “strate-

gic partnership” with Ukraine to turn the issue of the Ukrainians

in Poland into a matter of governmental concern at the forefront

of minority policy. In the evidence from the Interdepartmental

Group there are no examples of discussions that link Ukrainianminority demands with the issue of Polish international geopo-

litical interests.

This conclusion is supported by evidence from the Sejm com-

mission on ethnic and national minorities (Komisja Mniejszosci

Narodowych i Etnicznych). The main focus of debate in this com-

mission was the draft minority law, initially tabled in 1998. This

draft act not only contained provisions forbidding discrimination

and assimilation; it also made specific forms of affirmative actionpossible, mandated the establishment of a commission that would

become responsible for the implementation of government

East European Politics and Societies 493

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 21/29

policies towards minorities, and increased the possibilities for

utilizing minority languages in the public sphere in areas inhabited

by sizeable minority groups. It led to the adoption of the 2005 law

on national and ethnic minorities and regional language.In this commission, minority representatives were frequently

heard. At these occasions, the Ukrainian minority was repre-

sented by Miron Kertyczak, at that time the president of the

Association of Ukrainians in Poland. From the comments made

by Kertyczak in the commission, one can conclude that

Ukrainian affairs were seen very much in the context of the

demands made by minorities in general . For example, at various

times Kertyczak highlighted the importance of the minority law and expressed his hope that the work on that law would be con-

tinued and lead to the adoption of the law. He also emphasized

the importance of a sustained financial state support for the pub-

lication of minority magazines and journals. When it came to top-

ics more related to the specificities of Ukrainian-Polish relations,

the discussion revolved around the legacy of Operation Vistula.

Ukrainian activists demanded not only a final official condemna-

tion of Operation Vistula but also wanted to see an initiative fromthe policy makers to regulate material reparations and support

commemoration (e.g., through establishing monuments).

Of course, the debates in this parliamentary commission do

not provide us with an exhaustive overview of the political action

of the Ukrainian minority in Poland. They do, however, give us an

idea of what Ukrainian minority leaders have regarded as crucial

issues, that is, what issues they have hoped to bring into the

debate, or what issues they have hoped would stand a reason-able chance of being of some sort of influence in the parliamen-

tary debate on the subject. From this point of view it is

remarkable that in the interventions made by the president of

the Association of Ukrainians in Poland no link was made

between the situation of the Ukrainian minority in Poland and

the diplomatic efforts of the government to improve relations

with Ukraine.

In this context, the transcripts of the discussions held in theparliamentary Commission for EU Affairs (Komisja do Spraw Unii

Europejskiej) are also an interesting source of information.

494 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 22/29

Although Ukraine was an important topic of discussion in this

commission, it is striking that a number of other important top-

ics were not brought up by the participants. For example, one

will find no information on the opinion of the commissionmembers on the Ukrainian minority in Poland or on the way

Ukraine should deal with its Polish minorities. Furthermore,

there were no references to the historical context of Polish-

Ukrainian relations. The emphasis in this commission was clearly

on Poland’s current short-term goal: bringing Ukraine as close as

possible to EU accession. This issue was seen as completely sep-

arated from the debate on national minority protection. Andrzej

ZaÂucki, then vice secretary of state at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, summarized the general tenet of the debates in the com-

mission very aptly: “There is complete consensus and under-

standing not only with regard to Ukrainian aspirations, but also

with regard to the need to find a place for Ukraine in the

European family.”41 The need to find a place for Ukrainians in

Poland was apparently not seen as related to this issue. The vice

secretary of state at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jan

Truszczynski, made clear that in the context of improving bilat-eral relations between Poland and Ukraine the larger European

environment would be of crucial importance:

Our task and goal remains to date: developing and realizing theEuropean Neighbourhood Policy and persuading Ukraine that it isimportant to become involved in realizing this policy, to add another floor to the building that Ukraine has been able to put up so far incooperation with the EU.42

The conclusion that there is consensus among the main Polish

political actors about the need to support Ukrainian member-

ship of the EU, but that there is no need felt to create a link with

domestic discussions about historical antagonisms between

Poles and Ukrainians, is much in keeping with conclusions from

other research projects. One example is the analysis made by

Copsey and Szczerbiak of the political programs that Polish polit-

ical parties presented to their potential voters during the elec-tion campaign for the European parliamentary elections in June

2004.43 These authors found out that there was a broad consensus

East European Politics and Societies 495

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 23/29

among political parties about the way in which policy towards

Ukraine should be viewed. Virtually all of the parties encouraged

the development of a strong, independent and pro-Western

Ukraine as an important element in preserving Polish indepen-dence from Russia. Within this consensus, only some parties—

most notably the radical conservative League of Polish Families

(LPR)—formulated a policy on Ukraine that put emphasis on the

position of the Polish minority and the Catholic Church in

Ukraine, not on the process of democratization of Ukraine. Yet it

is to some extent remarkable that none of the parties, however

extreme, favored a policy of border revision or annexation of

border territories. And it is perhaps equally remarkable that noneof the parties, however pro-European and however in favor of

minority rights protection (such as, for example, the Freedom

Union, UW), used this international context to bring the situa-

tion of the Ukrainians in Poland into the center of attention.

Is there a European political opportunity structure for Ukrainian minority activism?

Has EU enlargement, then, in no way been a new political

opportunity for Ukrainian activism in Poland? To be sure, Poland’s

accession to the EU, with all its symbolic meaning of a “return to

Europe,” has been an important context for minority activism

because it brought with it the further dissemination of a resonat-

ing discourse of norms and standards for minority protection. It is

clear that Ukrainian minority activists have to a certain extent ben-

efited from this trend. Yet a deliberate strategy aimed at framingdomestic demands as matters related to Polish foreign policy

toward the EU and toward Ukraine has conspicuously lacked from

the Ukrainian minority’s political action repertoire. The issue of

support for the Ukrainian minority has been—institutionally and

in terms of official discourse—separated from the issue of Polish

support for Ukrainian membership of the EU.

It might be in order to think of plausible reasons for this fact.

One might think of a number of reasons that would point to the“nature” of the Ukrainian minority in Poland. One could, for

example, argue that due to past policies the Ukrainians in Poland

496 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 24/29

have become a strongly dispersed, rather fragmented, internally

diversified, and relatively assimilated group of people who there-

fore might not be interested in emphasizing a link with Ukraine.

One might even argue that it is not at all that sure that Ukrainiansin Poland have any interest at all in identifying with Ukraine and

its population. In other words, being a Ukrainian in Poland is

very different from being Ukrainian in Ukraine. It is indeed not

that easy to determine what being a Polish citizen of Ukrainian

descent really means for the people who identify themselves

with this category. We might hypothesize that there has been a

process of identification among the Ukrainians in Poland that has

led them away from Ukrainian identity in Ukraine. Or perhapsUkrainian identity in Poland has always been different from

Ukrainian identity in Ukraine.

More important than the patterns of identification among the

general Ukrainian population in Poland, however, are the pat-

terns of identification that Ukrainian minority activists have tried

to promote through political action. The Ukrainian minority

activists in Poland have apparently not attempted to forge a link

between Ukrainian minority identity in Poland and the positionof Ukraine in the international arena. In other words, activists

have not constructed this link to mobilize an audience. This is

important because it says something about the “identity project”

activists have tried to construct for the group they want to rep-

resent. The political project of the Ukrainian minority activists is

clearly not so much about creating a closer association with

Ukraine but rather about finding justice from the government

within the confines of the Polish state.This is shown by the content of the demands made by the

Ukrainian minority organizations. These demands have not been

about international relations, nor about the need to develop

better links with the external homeland. They have not been

about potential Ukrainian membership in the EU. They have not

been about the demands the EU has imposed on Poland, nor

about the EU’s potential influence on the democratization

process in Ukraine. They have mostly been about issues relatedto the development of local culture, reparations, monuments and

commemoration, and the preservation of culture and language

East European Politics and Societies 497

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 25/29

through publications and education in the context of the Polish

state. Their demands have not been about the preservation of

cross-border ties, the possibility of receiving support from

Ukraine, or the facilitation of travel and migration to and fromUkraine. From this one could conclude that Ukrainian minority

activists do not construct “Ukraine” as their national homeland,

but rather Poland, or more precisely, the Polish borderland

regions. Consider, for example, Miron Kertyczak’s plea to the

Polish public and to NGO representatives during his speech at

the opening of the exhibition about Operation Vistula at the state

archives in Warsaw in 2002:

Help subsequent generations to maintain bonds with their homelandthat their ancestors had been forced to leave. Because we intend tokeep returning there, to cultivate the memory of our native roots,sing songs, tend to graves, strengthen our scarce community thatinhabits the area from ñemkowszczyzna to Podlasie. We will maintainbonds with our native land. Because it was, is, and we believe that it

will remain for the centuries to come our small homeland in our country: the Republic of Poland.44

Such a point of view may have been not only the deliberate con-struction of Ukrianian minority activists. It may in part also have

been the result of the Ukrainian government’s lack of proactive

policy toward the Ukrainian minority in Poland. If neither the

Polish nor the Ukrainian government makes a strong connection

between foreign policy and the treatment of the Ukrainian minor-

ity in Poland, it is difficult for Ukrainian organizations to do so.

This last finding brings me to another important, more gen-

eral conclusion about the potential influence of Europeanizationon domestic minority politics. It points to the need to prob-

lematize the concept of “transnational political opportunity

structure.” Just as movement identities (including ethnicity) are

constructed by a range of actors in the course of collective action

(rather than that they are a stable source of collective action),

one can argue that transnational political opportunities are con-

structed during the process of mobilization. As has been noted

in another context, identifying these political opportunities isnot at all an easy affair.45 To know whether institutional and polit-

ical developments on the transnational level can function as

498 A Minority at the Border

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 26/29

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 27/29

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 28/29

Sociology 26 (2000): 611-39; McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald, Comparative Perspectives on

Social Movements; and David S. Meyer, “Protest and Political Opportunities,” Annual

Review of Sociology 30 (2004): 125-45.

10. See Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Activists beyond Borders: Transnational Advocacy

Networks in International Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998).

11. See John A. Guidry, Michael D. Kennedy, and Mayer N. Zald, eds., Globalizations and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere (Ann Arbor: University

of Michigan Press, 2000).

12. Thomas Risse and Kathryn Sikkink, “The Socialization of International Human Rights Norms

into Domestic Practices: Introduction,” in T. Risse, S. C. Ropp, and K. Sikkink, eds., The

Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1999), 1-38.

13. See Judith Kelley, Ethnic Politics in Europe: The Power of Norms and Incentives (Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

14. Romano Prodi, “A Wider Europe—A Proximity Policy as the Key to Stability.” (Speech deliv-

ered at the Sixth ECSA-World Conference, “Peace, Security and Stability International

Dialogue and the Role of the EU,” Brussels, Belgium, 5-6 December 2002.)

15. Benita Ferrero-Waldner, “Article on the Occasion of the Inauguration of the New Presidentof Ukraine,” http://www.delukr.cec.eu.int/site/page34090.html (accessed 22 January 2005).

16. Judy Batt, “Managing the New External Borders.” (Paper presented at the Conference on

Legitimacy and Accountability in the European Union after Nice, Institute of European Law,

University of Birmingham, UK, 6 July 2001.)

17. Liam O’Dowd and Thomas M. Wilson, “Frontiers of Sovereignty in the New Europe,” in Liam

O’Dowd and Thomas M. Wilson, eds., Borders, Nations and States (Aldershot, UK: Avebury,

1996), 13.

18. Sandra Lavenex, “Migration and the EU’s New Eastern Border: Between Realism and

Liberalism,” Journal of European Public Policy 8:1(2001): 24-42.

19. For a fuller treatment of this issue, see Peter Vermeersch, “EU Enlargement and Immigration

Policy in Poland and Slovakia,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 38:2(2005): 71-88.

20. See Lesya Fediv, “Pole-axed,” Transitions Online, 30 January 2004. See also AndrzejMiszczuk, “Pogranicze polsko-ukrainskie a polityka zagraniczna III RP,” in Ryszard

Stemplowksi and Adriana Z.elazo, eds., Polskie pogranicza a polityka zagraniczna u progu

XXI wieku (Warsaw, Poland: Polski Instytut Spraw Mie[dzynarodowych, 2002), 263-80.

21. O’Dowd and Wilson, “Frontiers of Sovereignty,” 1.

22. Kataryna Wolczuk and Roman Wolczuk, Poland and Ukraine. A Strategic Partnership in a

Changing Europe? (London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2002), esp. 6-28.

23. Vermeersch, “EU Enlargement and Immigration Policy,” 84.

24. In 2004, the new visa regime caused huge waiting lines at the Polish consulates in Ukraine.

The press reported complaints of corruption. For a discussion, see Jagienka Wilczak, “Wizy

za dewizy,” Polityka 25:2457(2004): 30-33.

25. WacÂaw Radziwinowicz, “Polska be[dzie mediowac na Ukrainie?” Gazeta Wyborcza, 5 April 2007.

26. Wolczuk and Wolczuk, Poland and Ukraine, 3.27. Chris Hann, “Postsocialist Nationalism: Rediscovering the Past in Southeast Poland,” Slavic

Review 57:4(1998): 843.

28. Timothy Snyder, “‘To Resolve the Ukrainian Problem Once and for All’: The Ethnic Cleansing

of Ukrainians in Poland, 1943-1947,” Journal of Cold War Studies 1:2(1999): 88.

29. Sir Walter Napier’s speech delivered in 1932 at the UK’s Royal Institute of International

Affairs is a good illustration. He said, “The tasks which the Poles had taken upon themselves

was to constitute out of the various races within their territories a united State which,

though composed of several nationalities, would be imbued with Western ideals of civiliza-

tion and would form a bulwark against the westward trend of Bolshevik principles. . . . It

is difficult to escape the conclusion that so far Polish efforts have resulted in increasing

rather than in lessening the racial ill-feeling” (Walter Napier, “The Ukrainians in Poland: An

Historical Background,” International Affairs 11:3[1932]: 408-9).30. MirosÂaw Czech, “Kwestia ukrainska w III Rzeczypospolitej,” In Ukraincy w Polsce 1989-

1993: Kalendarium, dokumenty, informacje (Warsaw, Poland: Zwia[zek Ukrainców w

Polsce, 1993), 268-89.

East European Politics and Societies 501

at Uni Lucian Blaga on January 19, 2013eep.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8/12/2019 EU Enlargement and the Ukrainian Minority in Poland

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/eu-enlargement-and-the-ukrainian-minority-in-poland 29/29

31. Czech, “Kwestia ukrainska,” 268.

32. Snyder, “To Resolve the Ukrainian Problem,” 86-120.

33. Czech, “Kwestie ukrainska,” 269.

34. In elections in 1993 and 1997, other candidates representing the Ukrainian minority were

elected as MPs from lists of the liberal Freedom Union (UW) and the Alliance of the

Democratic Left (SLD).35. Ukrainskie Towarzystwo SpoÂeczno-Kulturalne, “1989 luty 26, Warszawa—Raport Ukrainskiego

Towarzystwa SpoÂeczno-Kulturalnego pt. ‘Ukraincy w Polsce Ludowej,’” in Ukraincy w Polsce

1989-1993, 86.

36. Czech, “Kwestia ukrainska,” 275.

37. Quoted in the editorial of The Ukrainian Weekly, 12 May 2002.38. Joanna Konieczna, “Polacy-Ukraincy, Polska-Ukraina. Paradoksy stosunków sa

[siedzkich.”

(Working paper published by the Batory Foundation, Warsaw, Poland, 2003.)

39. These documents are available from the following Web sites: http://www.mswia.gov.pl/

spr_oby_mn3.html, http://www.sejm.gov.pl/komisje/www_mne.htm, http://www.sejm.gov.pl/

komisje/www_sue.htm.

40. Articles 23 and 24 of Law 141, “Ustawa o mniejszo sciach narodowych i etnicznych oraz o

je[zyku regionalnym” (Dziennik Ustaw nr. 17). The current representatives of the Ukrainianminority in this body are Piotr Tyma and Grzegorz Kuprianowicz.

41. Komisja do Spraw Unii Europejskiej, Biuletyn nr. 4190/IV , 19 February 2005.

42. Komisja do Spraw Unii Europejskiej, Biuletyn nr. 3471/IV , 23 July 2004.

43. Nathaniel Copsey and Aleks Szczerbiak, “The Future of Polish-Ukrainian Elections: Evidence

from the June 2004 European Parliament Election Campaign in Poland.” (Working paper 48,

Sussex European Institute, UK, 2005.)

44. See http://www.interklasa.pl/portal/dokumenty/r_mowa/.

45. David S. Meyer, “Protest and Political Opportunities,” Annual Review of Sociology 30 (2004):

125-45.

502 A Minority at the Border

Related Documents