THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PERCEPTIONS OF ORGANIZATIONAL POLITICS AND EMPLOYEE ATTITUDES, STRAIN, AND BEHAVIOR: A META-ANALYTIC EXAMINATION CHU-HSIANG CHANG University of South Florida CHRISTOPHER C. ROSEN University of Arkansas PAUL E. LEVY University of Akron The current study tested a model that links perceptions of organizational politics to job performance and “turnover intentions” (intentions to quit). Meta-analytic evidence supported significant, bivariate relationships between perceived politics and strain (.48), turnover intentions (.43), job satisfaction (.57), affective commitment (.54), task performance (.20), and organizational citizenship behaviors toward individuals (.16) and organizations (.20). Additionally, results demonstrated that work atti- tudes mediated the effects of perceived politics on employee turnover intentions and that both attitudes and strain mediated the effects of perceived politics on perfor- mance. Finally, exploratory analyses provided evidence that perceived politics repre- sent a unique “hindrance stressor.” Organizational politics are ubiquitous and have widespread effects on critical processes (e.g., per- formance evaluation, resource allocation, and man- agerial decision making) that influence organi- zational effectiveness and efficiency (Kacmar & Baron, 1999). Employees may engage in some legitimate, organizationally sanctioned political ac- tivities that are beneficial to work groups and or- ganizations (see Fedor, Maslyn, Farmer, & Betten- hausen, 2008). For example, managers who are “good politicians” may develop large bases of so- cial capital and strong networks that allow them to increase the resources that are available to their subordinates (Treadway et al., 2004). On the other hand, employees also demonstrate a number of il- legitimate political activities (e.g., coalition build- ing, favoritism-based pay and promotion decisions, and backstabbing) that are strategically designed to benefit, protect, or enhance self-interests, often without regard for the welfare of their organization or coworkers (Ferris, Russ, & Fandt, 1989). There- fore, organizational politics are often viewed as a dysfunctional, divisive aspect of work environ- ments (Mintzberg, 1983). The current article fo- cuses on understanding how employees’ percep- tions of illegitimate, self-serving political activities (viz., perceptions of organizational politics) influ- ence individual-level work attitudes and behaviors. Accumulating empirical research has provided considerable evidence for linkages between percep- tions of organizational politics and a variety of employee outcomes, including job satisfaction, af- fective organizational commitment, and job anxiety (see Ferris, Adams, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, & Ammeter, 2002). However, despite the intuitive ap- peal of the idea that perceived politics will have an impact on key individual-level outcomes associ- ated with organizational effectiveness, research has failed to consistently demonstrate such an impact. For example, Ferris et al. (2002) observed that four of nine studies (e.g., Cropanzano, Howes, Grandey, & Toth, 1997; Hochwarter, Witt, & Kacmar, 2000; Parker, Dipboye, & Jackson, 1995; Randall, Cropan- zano, Bormann, & Birjulin, 1999) relating percep- tions of organizational politics to task performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) did not support the expected negative linkages. Simi- larly, four of nine studies (e.g., Cropanzano et al., We thank Brad Kirkman and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful insights. We would like to note that the first two authors contributed equally to this project. We would like to thank Rosalie Hall for her helpful comments on an earlier version of the article. We are also grateful for the assistance of Michelle Matias and Jessica Junak in preparing our manuscript. Academy of Management Journal 2009, Vol. 52, No. 4, 779–801. 779 Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder’s express written permission. Users may print, download or email articles for individual use only.

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PERCEPTIONS OFORGANIZATIONAL POLITICS AND EMPLOYEE ATTITUDES,

STRAIN, AND BEHAVIOR: AMETA-ANALYTIC EXAMINATION

CHU-HSIANG CHANGUniversity of South Florida

CHRISTOPHER C. ROSENUniversity of Arkansas

PAUL E. LEVYUniversity of Akron

The current study tested a model that links perceptions of organizational politics to jobperformance and “turnover intentions” (intentions to quit). Meta-analytic evidencesupported significant, bivariate relationships between perceived politics and strain(.48), turnover intentions (.43), job satisfaction (�.57), affective commitment (�.54),task performance (�.20), and organizational citizenship behaviors toward individuals(�.16) and organizations (�.20). Additionally, results demonstrated that work atti-tudes mediated the effects of perceived politics on employee turnover intentions andthat both attitudes and strain mediated the effects of perceived politics on perfor-mance. Finally, exploratory analyses provided evidence that perceived politics repre-sent a unique “hindrance stressor.”

Organizational politics are ubiquitous and havewidespread effects on critical processes (e.g., per-formance evaluation, resource allocation, and man-agerial decision making) that influence organi-zational effectiveness and efficiency (Kacmar &Baron, 1999). Employees may engage in somelegitimate, organizationally sanctioned political ac-tivities that are beneficial to work groups and or-ganizations (see Fedor, Maslyn, Farmer, & Betten-hausen, 2008). For example, managers who are“good politicians” may develop large bases of so-cial capital and strong networks that allow them toincrease the resources that are available to theirsubordinates (Treadway et al., 2004). On the otherhand, employees also demonstrate a number of il-legitimate political activities (e.g., coalition build-ing, favoritism-based pay and promotion decisions,and backstabbing) that are strategically designed tobenefit, protect, or enhance self-interests, oftenwithout regard for the welfare of their organization

or coworkers (Ferris, Russ, & Fandt, 1989). There-fore, organizational politics are often viewed as adysfunctional, divisive aspect of work environ-ments (Mintzberg, 1983). The current article fo-cuses on understanding how employees’ percep-tions of illegitimate, self-serving political activities(viz., perceptions of organizational politics) influ-ence individual-level work attitudes and behaviors.

Accumulating empirical research has providedconsiderable evidence for linkages between percep-tions of organizational politics and a variety ofemployee outcomes, including job satisfaction, af-fective organizational commitment, and job anxiety(see Ferris, Adams, Kolodinsky, Hochwarter, &Ammeter, 2002). However, despite the intuitive ap-peal of the idea that perceived politics will have animpact on key individual-level outcomes associ-ated with organizational effectiveness, research hasfailed to consistently demonstrate such an impact.For example, Ferris et al. (2002) observed that fourof nine studies (e.g., Cropanzano, Howes, Grandey,& Toth, 1997; Hochwarter, Witt, & Kacmar, 2000;Parker, Dipboye, & Jackson, 1995; Randall, Cropan-zano, Bormann, & Birjulin, 1999) relating percep-tions of organizational politics to task performanceand organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) didnot support the expected negative linkages. Simi-larly, four of nine studies (e.g., Cropanzano et al.,

We thank Brad Kirkman and the three anonymousreviewers for their helpful insights. We would like tonote that the first two authors contributed equally to thisproject. We would like to thank Rosalie Hall for herhelpful comments on an earlier version of the article. Weare also grateful for the assistance of Michelle Matias andJessica Junak in preparing our manuscript.

� Academy of Management Journal2009, Vol. 52, No. 4, 779–801.

779

Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder’s expresswritten permission. Users may print, download or email articles for individual use only.

1997; Harrell-Cook, Ferris, & Dulebohn, 1999;Hochwarter, Perrewe, Ferris, & Guercio, 1999; Ran-dall et al., 1999) examining linkages between polit-ical perceptions and turnover intentions failed toreach statistical significance (Ferris et al., 2002).Thus, evidence linking perceptions of organization-al politics to these outcomes is equivocal.

Moreover, it is not clear whether these inconsis-tent findings exist because of statistical artifacts(e.g., low power) or because the politics-outcomerelationships are not negative. Regarding the latterpoint, Ferris et al. (1989) noted that employees mayrespond to perceptions of organizational politics byincreasing involvement in their jobs. Ferris et al.(1989) suggested that perceived politics may lead topositive outcomes when they are experienced asopportunity stress (Schuler, 1980), which occurswhen a stressor presents an opportunity for em-ployees to gain something from the situation athand. Employees respond to opportunity stress byputting more time and effort into their jobs in anattempt to capitalize on the situation (LePine, Pod-sakoff, & LePine, 2005; Schuler, 1980). Supportingthis perspective, there is evidence that perceptionsof organizational politics are associated with desir-able outcomes, including lower strain (Ferris et al.,1993), and increased job involvement (Ferris & Kac-mar, 1992) and performance (Maslyn & Fedor,1998; Rosen, Levy, & Hall, 2006). Thus, it is notclear whether inconsistent findings in the literatureare a function of study artifacts or exist becauseperceptions of organizational politics are either notrelevant to or positively associated with certainoutcomes.

In addition, the theoretical underpinnings of thelinkages between perceptions of organizational pol-itics and job performance and turnover intentionsare not well understood, as existing frameworks donot explain how these perceptions are associatedwith critical employee outcomes. Rather, concep-tual models (e.g., Aryee, Chen, & Budhwar, 2004;Ferris et al., 2002) specify that perceptions of or-ganizational politics are related directly to em-ployee attitudes and behaviors. Hence, knowledgeof the psychological mechanisms that relate politi-cal perceptions to employee outcomes is limited,and there is little guidance for systematically ex-amining these mechanisms. In addition, researchhas failed to examine mediators that link percep-tions of organizational politics to outcomes. Forexample, theorists have noted that job stress andsocial exchange theories may explain reactions tothese perceptions (Cropanzano et al., 1997; Ferris etal., 2002). However, the dearth of empirical re-search examining the linkages implied by thesetheories has limited researchers’ ability to deter-

mine if one, both, or neither of these explanationsaccounts for the effects of perceptions of organiza-tional politics.

A recent meta-analysis of the outcomes of per-ceptions of organizational politics (see Miller,Rutherford, & Kolodinsky, 2008) underscores someof these empirical and theoretical weaknesses inthe politics literature. Empirically, Miller et al.’s(2008) results failed to clearly support a linkagebetween perceptions of organizational politics andperformance. Moreover, their study (1) did notpresent an overarching theoretical framework thatexplains why perceived organizational politics islinked to employee attitudes and behaviors and (2)focused only on bivariate linkages between the con-struct and its outcomes, without considering howoutcomes of perceptions of organizational politicsrelate to one another. The current research ad-dresses these shortcomings of the literature on per-ceptions of organizational politics in three ways.First, this study provides a comprehensive, quanti-tative review of the relationships between per-ceived organizational politics and its outcomes.Meta-analysis allowed estimation of the true pop-ulation effect size (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004) andexamination of whether study characteristics ex-plain variability in effect sizes. Thus, a meta-ana-lytic examination of the perceptions of organiza-tional politics–outcome relationships is importantbecause it helps determine whether the past incon-sistent findings were the result of statistical arti-facts or, rather, were associated with a broader is-sue, such as the misspecification of relationshipsbetween perceptions of organizational politics andits outcomes.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, the cur-rent study focuses on developing and testing a the-oretically derived model that identifies the key psy-chological mechanisms that link perceivedorganizational politics to its distal outcomes. Fig-ure 1 outlines the proposed model, which inte-grates the organizational politics literature withtheoretical frameworks that specify the causal or-dering of stress-related outcomes (Podsakoff,LePine, & LePine, 2007; Schaubroeck, Cotton, &Jennings, 1989). This approach is consistent withprevious studies (LePine et al., 2005; Podsakoff etal., 2007) that have cast organizational politics as ahindrance stressor that prevents employees frommeeting personal and professional goals. We testedthe validity of the proposed model using meta-analytically derived correlations. Thus, the contri-bution of our meta-analysis is enhanced by its abil-ity to not only provide information on the strengthof the bivariate relationships between constructs,

780 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

but also explain how the focal constructs are related(Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995).

Finally, we explore whether perceptions of or-ganizational politics can be distinguished fromother hindrance stressors. Although some research-ers have argued that it is best to treat various stres-sors as distinct yet related constructs (Schaubroecket al., 1989), the hindrance stressor literature im-plies that perceptions of organizational politics,role ambiguity, and role conflict are all indicatorsof a higher-order hindrance stressor factor (LePineet al., 2005; Podsakoff et al., 2007). Thus, we con-ducted exploratory analyses to compare relation-ships among perceptions of organizational politics,role stressors, and outcomes and to evaluate mod-els based on different conceptualizations of thehindrance stressor construct.

BACKGROUND AND THEORY

Theorists have provided two explanations thatlink perceptions of organizational politics to nega-tive work outcomes. First, Ferris et al. (1989) sug-gested that politics are a source of stress that elicitsstrain responses from employees. Other theoristshave suggested that perceptions of organizationalpolitics are detrimental to the maintenance ofhealthy employee-organization exchange relation-ships (Aryee et al., 2004; Hall, Hochwarter, Ferris,& Bowen, 2004). Below, we review these explana-tions of the effects of perceived organizational pol-itics and apply Schaubroeck et al.’s (1989) frame-work of work stress to tie these perspectivestogether. Finally, we develop a model based on thehindrance stressor literature to link perceptions of

FIGURE 1Proposed and Alternative Models of Effects of Perceptions of Organizational Politics on

Employee Outcomes

2009 781Chang, Rosen, and Levy

organizational politics to proximal (strain and atti-tudes) and distal (performance and turnover inten-tions) outcomes.

Stress-Based Effects of Perceptions ofOrganizational Politics

Drawing on research conceptualizing job stressas a subjective experience associated with uncer-tainty and ambiguity (e.g., Schuler, 1980), Ferris etal. (1989) proposed that perceptions of organiza-tional politics represent a stressor that is directlyrelated to attitudinal and behavioral reactions. Fer-ris et al. speculated that perceptions of organiza-tional politics trigger a primary appraisal (Lazarus& Folkman, 1984) that a work context is threateningand put pressure on employees to engage in poli-ticking to meet their goals. Highly political organi-zations tend to reward employees who (1) engage instrong influence tactics, (2) take credit for the workof others, (3) are members of powerful coalitions,and (4) have connections to high-ranking allies. Asorganizations reward these activities, demands areplaced on workers to engage in political behaviorsto compete for resources. According to the job de-mands–resource model of work stress (Demerouti,Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001), employeeswho perceive that job demands exceed their copingresources feel overwhelmed. This emotional strainrequires additional coping efforts, which are takenaway from resources that could otherwise be de-voted to job performance. Excessive strain also im-pacts employee health (Dragano, Verde, & Siegrist,2005) and eventually drives employees to searchfor less stressful work environments.

A Social Exchange Perspective on the Effects ofPerceptions of Organizational Politics

In highly political organizations, rewards are tiedto relationships, power, and other less objectivefactors. As a result, “the immediate environmentbecomes unpredictable because the unwritten rulesfor success change as the power of those playingthe political game varies” (Hall et al., 2004: 244).Therefore, it is difficult for employees to predict iftheir behaviors will lead to rewards in politicalwork contexts, and they are likely to perceiveweaker relationships between performance and theattainment of desired outcomes (Aryee et al., 2004;Cropanzano et al., 1997). Supporting this perspec-tive, Rosen et al. (2006) demonstrated that percep-tions of organizational politics are associated withperformance through employee morale. In theirstudy, as in the present study, employee moraleand job performance were conceptualized as aggre-

gate latent constructs. The morale construct repre-sented general employee attitudes and was com-prised of job satisfaction and affective commitment(see Harrison, Newman, & Roth, 2006), and theperformance construct consisted of task perfor-mance and OCB (see Rotundo & Sackett, 2002),which captured behaviors related to both the tech-nical cores of organizations and behaviors that con-tribute to the psychosocial contexts of workplaces(Organ, 1997). Rosen et al. (2006) suggested thatlower morale reflects judgments that reward allo-cation processes are arbitrary and unfair. Employ-ees holding less favorable attitudes also feel lessobligated to reciprocate with behaviors that en-hance the well-being of their organization. Thus,Rosen et al. provided evidence, albeit indirectly,that morale is part of the social exchange mecha-nism that links perceptions of organizational poli-tics to performance.

Current Study: Model and Hypotheses

The stress and social exchange perspectives areuseful to understanding reactions to perceptions oforganizational politics. Nonetheless, research fallsshort in describing the mechanisms that link suchperceptions to outcomes. For example, Ferris etal.’s (2002) model specifies that job anxiety, jobsatisfaction, affective commitment, performance,and turnover intentions are direct outcomes of per-ceptions of organizational politics, with each reac-tion occurring at the same time. However, there arereasons to believe that some reactions to politicalperceptions precede others. In particular, workstress research (Schaubroeck et al., 1989) suggeststhat job anxiety, job satisfaction, and affective com-mitment are antecedents to turnover intentions andperformance. Therefore, we suggest that percep-tions of organizational politics have indirect effectson turnover intentions and performance throughmore immediate outcomes (viz., strain and morale).As such, previous studies examining only the di-rect effects of perceptions of organizational politicson performance and turnover intentions may havemisspecified these linkages, thus biasing the studyresults (Duncan, 1975).

The stress and social exchange perspectives em-ploy a similar logic useful for understanding em-ployees’ reactions to perceptions of organizationalpolitics. Particularly, both perspectives suggest thatthese perceptions are associated with ambiguityand uncertainty in a work environment that resultsin psychological strain and lower morale. However,neither perspective describes how these outcomesof perceptions of organizational politics relate toeach other and whether these outcomes have a

782 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

meaningful impact on more distal reactions. Fortu-nately, the work stress literature provides insightregarding the causal ordering of these reactions tostressors. Following Mobley, Horner, and Holling-sworth’s (1978) model of turnover, Schaubroeck etal. (1989) specified that role stressors lead to in-creased job strain, which is associated with lowerjob satisfaction and affective commitment and, sub-sequently, increased turnover intentions. Podsakoffet al. (2007) and LePine et al. (2005) employedsimilar mediational chains to explain the effects ofhindrance stressors on turnover and task perfor-mance. Moreover, Cropanzano, Rupp, and Byrne(2003) demonstrated that the effects of strain workthrough morale and impact OCBs, in addition totask performance. Together, these studies providecomplementary approaches to understanding theeffects of stressors.

We incorporate these perspectives into a modelthat conceptualizes perceptions of organizationalpolitics as a hindrance stressor reflecting job de-mands that interfere with employees’ ability toachieve career goals. Hindrance stressors arebroadly defined as constraints that impede individ-uals’ work achievements and are not usually asso-ciated with potential net gains for them (LePine etal., 2005). In addition to perceptions of organiza-tional politics, researchers include role stressors,bureaucracy, and daily hassles under the umbrellaof hindrance stressors. Collectively, research hasshown that these stressors elicit strain, reduce mo-rale, motivation, and performance, and increaseemployee withdrawal (Boswell, Olson-Buchanan,& LePine, 2004; Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, &Boudreau, 2000; Podsakoff et al., 2007). In keepingwith previous research examining the effects ofperceptions of organizational politics and hin-drance stressors, we argue that politics hamper em-ployees’ ability to attain personal and professionalgoals, which results in a primary appraisal of thework context that evokes strain and reduces mo-rale. In accordance with the causal ordering sup-ported by previous studies, we also propose thatstrain is a more proximal outcome than morale.This proposition derives from both the stress andsocial exchange perspectives. Work stress research-ers (Schaubroeck et al., 1989) have suggested thatpsychological strain influences employees’ overallattitudes toward their jobs, as employees considertheir jobs to be the root of the problem. Strain isalso purported to reflect a negative evaluation ofthe employee-organization exchange relationship(Cropanzano et al., 1997). Thus, as strain increases,employees’ morale and sense of obligation towardtheir organization decline (Cropanzano et al.,2003).

We propose that perceptions of organizationalpolitics have both direct and indirect effects onmorale. In turn, psychological strain and moralelink perceptions of organizational politics to moredistal outcomes. In other words, employees’ perfor-mance suffers because they must focus time andeffort on coping with the strain associated withperceptions of organizational politics. In addition,employees are likely to reduce the time and effortthat they put into their jobs in response to per-ceived disequilibrium in the exchange relation-ship, which is reflected by lower morale. Finally,employees will attempt to remove themselves fromsituations appraised as unfavorable or threatening.In summary, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1. Perceptions of organizationalpolitics has a positive relationship with psy-chological strain.

Hypothesis 2. Perceptions of organizationalpolitics has a (a) direct negative relationshipwith morale (b) partially mediated by psycho-logical strain.

Hypothesis 3. Perceptions of organizationalpolitics has a positive relationship with turn-over intentions.

Hypothesis 4. Perceptions of organizationalpolitics has a negative relationship with jobperformance.

Hypothesis 5. The relationship between per-ceptions of organizational politics and turn-over intentions is mediated by (a) psychologi-cal strain and (b) morale.

Hypothesis 6. The relationship between per-ceptions of organizational politics and job per-formance is mediated by (a) psychologicalstrain and (b) morale.

Exploratory Analyses: Comparing Politics toOther Hindrance Stressors

In Schaubroeck et al.’s (1989) model, role ambi-guity and role conflict represent distinct, yet re-lated, stressors. More recently, researchers (e.g.,LePine et al., 2005; Podsakoff et al., 2007) havesuggested that a unified hindrance stressor con-struct encompasses perceptions of organizationalpolitics and role stressors. Perceived politics androle stressors certainly share the similarity of inter-fering with employees’ ability to achieve personaland professional goals. However, conceptualizingthese three constructs as indicators of a unifiedhindrance stressor construct entails an assumptionthat perceptions of organizational politics and role

2009 783Chang, Rosen, and Levy

stressors are analogous and demonstrate similar re-lationships with each other and with outcomes.Unfortunately, this assumption has not been empir-ically tested. Therefore, we provide supplementalanalyses that, first, compare relationships amongperceptions of organizational politics, role stres-sors, and outcomes, and second, explore whetherpolitical perceptions and role stressors are bestconceptualized as a unified construct or as a set ofdiversified yet related stressors. Figure 2 graphi-cally depicts these two contrasting patterns. Third,our additional analyses also explore whether per-ceptions of organizational politics and role stres-sors demonstrate similar patterns of relationshipswith distal outcomes. Similar relationships witheach other and with outcomes and a better-fittingmodel based on a unified hindrance stressor con-struct would provide further evidence for the uni-fied approach (Podsakoff et al., 2007). On the otherhand, differing relationship patterns and a better fitfor the diversified model would imply that percep-tions of organizational politics may have meaning-ful differences with other role-based hindrancestressors.

Research Question. Are perceptions of organi-zational politics and role stressors (role ambi-guity and role conflict) distinct forms of hin-drance stressors?

METHODS

Literature Search and Inclusion Criteria

To identify studies that could be used in thismeta-analysis, we first conducted a computerizedsearch of three databases (PSYCINFO, ABI-INFORM,and Business Source Premier) for the years between1989 (the year that Ferris and colleagues proposedthe perceptions of organizational politics con-struct) and 2007. We combined keywords associ-ated with politics (i.e., “organizational politics,”“politics perceptions,” and “perceived politics”)with keywords related to outcomes (general out-comes: “outcome,” “consequence,” and “result”;strain1: “strain,” “stress,” “stressor,” “anger,” “anx-iety,” “depress[ion],” “frustration,” “tension,” and“burnout”; morale: “job/work satisfaction,” “organ-izational/work commitment,” “affective commit-ment”; turnover intentions: “turnover,” “intent toturnover,” “withdrawal cognitions”; supervisor-

rated performance: “performance,” “productivity,”“task/job performance,” “organizational citizen-ship behavior,” “OCB,” “OCBI” [OCB toward indi-viduals], “OCBO” [OCB toward organizations], and“contextual performance”). Second, we manuallysearched the 1989–2007 issues of eight high-qual-ity journals that have published articles related toorganizational politics: the Academy of Manage-ment Journal, Journal of Applied Psychology, Jour-nal of Management, Journal of OrganizationalBehavior, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Organi-zational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,Organization Science, and Personnel Psychology.Third, we compared the reference list derived fromthe sources described so far with the lists of twoqualitative reviews of research on perceptions oforganizational politics (Ferris et al., 2002; Kacmar& Baron, 1999). Finally, we contacted researchersin the field for “file-drawer studies” and posted acall for unpublished papers on discussion lists forthe Society for Industrial/Organizational Psychol-ogy and the Academy of Management. In total, weidentified 57 relevant papers dealing with 70 sep-arate samples that we could include in themeta-analyses.

Three inclusion criteria were used. First, we in-cluded studies in the meta-analysis if they investi-gated relationships between perceptions of organi-zational politics and at least one of the dependentvariables. Second, we included studies that mea-sured politics perceptions and excluded studiesthat measured other operationalizations of organi-zational politics. The majority of studies used vari-ations of the perceptions of organizational politicsmeasure (Kacmar & Ferris, 1991); three exceptionswere Anderson (1994), Christiansen, Villanova,and Mikulay (1997), and Drory (1993). Kacmar andBaron’s (1999) qualitative review suggested that thethree scales in those studies assess perceptions oforganizational political climate. In addition, ourown content analysis revealed that items fromthese scales have counterparts in the perceptions oforganizational politics measure. Thus, we includedthese in the current meta-analysis.2 Finally, we in-cluded studies reporting relationships betweenperceptions of organizational politics and depen-

1 Two-thirds of the samples we found (14 out of 21)used the Work Tension Scale by House and Rizzo (1972)to assess psychological strain associated with tensionexperienced at work.

2 We also conducted meta-analyses without thesestudies for the applicable analyses and found the resultsshowed minor, nonsignificant fluctuations. After remov-ing these studies, we observed these changes in relation-ships: (a) perceptions of organizational politics andstrain, from .48 to .47; (b) politics and job satisfaction,from �.57 to �.58; (c) politics and affective commitment,from �.54 to �.55; and (d) politics and withdrawal in-tentions, from .43 to .44.

784 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

dent variables that were calculated from an originalsample. When the same sample was used in multi-ple studies, sample characteristics and effect sizes

were cross-referenced, and only one effect size wasincluded. Correlations were considered as separateentries when they represented relationships be-

FIGURE 2Conceptualizations of Hindrance Stressor

2009 785Chang, Rosen, and Levy

tween perceptions of organizational politics and (1)distinctive outcome variables and (2) one depen-dent variable, but from different samples (Arthur,Bennett, & Huffcutt, 2001). We aggregated correla-tions representing relationships between percep-tions of organizational politics and different mea-sures of the same outcome variable. These criteriaresulted in 21 effect sizes for strain, 45 for jobsatisfaction, 33 for affective commitment, 27 forturnover intentions, 14 for task performance, 9 forOCBI, and 9 for OCBO.

Meta-analytic and Model-Testing Procedures

We first used meta-analysis to summarize rela-tionships between perceptions of organizationalpolitics and each of the outcome variables. Whenavailable, we also examined whether the publica-tion status of a study, the employment status of thesampled population (full-time employees vs. em-ployed students), and the country from which thedata were collected, accounted for differences ineffect sizes among studies. Following Arthur et al.’s(2001) strategy, we calculated a sample-weightedmean correlation. We then computed the percent-age of variance accounted for by sampling error(Hunter & Schmidt, 2004) and performed the chi-square test for the homogeneity of observed corre-lation coefficients across studies (Rosenthal, 1991).The 95% confidence interval around the sample-weighted mean correlation was then computed us-ing different formulas depending on chi-square testresults (Whitener, 1990). We then corrected for un-reliability of measures to derive the population cor-relation coefficient. We used interrater reliabilityestimates from Viswesvaran, Ones, and Schmidt(1996) to correct for measurement error in the rela-tionships between perceptions of organizationalpolitics and supervisor-rated performance. Thevariance and standard deviation of the populationestimate were then calculated to determine the95% credibility interval. We also calculated theQ-statistic to examine variance in the correctedpopulation estimate. When the credibility intervalincluded zero or Q was significant, we performedsubgroup analyses to examine the moderating ef-fects of study characteristics (Cortina, 2003). Themoderator analyses included an examination ofboth publication status and sample employmentstatus, as well as a cross-cultural comparison be-tween U.S. and Israeli samples, none of which wereexamined in Miller et al.’s (2008) meta-analysis ofthe outcomes of perceptions of organizationalpolitics.

Next, we built a correlation matrix containing thecorrected population correlation coefficients be-

tween all the variables using the current and pre-vious meta-analytic results. Selected meta-analysespublished since 1995 provided estimates for rela-tionships among nonpolitics variables. Table 1 pre-sents this correlation matrix. We performed struc-tural equation modeling (SEM) based on thiscorrelation matrix to evaluate the fit of the pro-posed model. We adopted Shadish (1996) and Vi-swesvaran and Ones’s (1995) procedures for modeltesting. Unless otherwise noted, the structuralmodel used manifest indicators without correctionfor measurement error, as these corrections weredone through meta-analysis. Finally, because nopublished meta-analysis estimates the relation-ships between turnover intentions and OCBI andOCBO, we used primary studies found for the cur-rent meta-analysis to estimate these relationships(see Harrison et al., 2006). Specifically, seven of thenine samples that we found in our meta-analysisfor the relationships between perceptions of organ-izational politics and OCBI and OCBO includedturnover intentions as an outcome variable. Rela-tionships between turnover intentions and OCBswere extracted from these seven studies and meta-analyzed to provide estimates for the meta-analyticcorrelation matrix.

For the exploratory analyses, we performed anadditional literature search for meta-analytic corre-lations involving role stressors (i.e., role ambiguityand role conflict) and the outcome variables in-cluded in the current study (e.g., Ortqvist & Win-cent, 2006; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Bommer,1996). We then incorporated these correlations intothe meta-analytic correlation matrix (Table 1) andtested the proposed model using the two differentconceptualizations of the hindrance stressor con-struct (i.e., as a unified vs. diversified construct).Because no published meta-analysis estimated therelationships between perceptions of organization-al politics and the two role stressors, we used avail-able primary studies to estimate these relationships(six effect sizes for the perceptions of organization-al politics–role ambiguity relationship [� � .52];four effect sizes for the perceptions of organiza-tional politics–role conflict relationship [� � .58]).

RESULTS

Bivariate Relationships

Table 2 shows the results of the meta-analysis forthe relationships between politics and strain, jobsatisfaction, affective commitment, turnover inten-tions, task performance, OCBI, and OCBO. All ofthe 95% confidence intervals excluded zero, indi-cating that each correlation was statistically signif-

786 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

icant (p � .05). In addition, all of the 95% credibil-ity intervals excluded zero, suggesting that allbivariate relationships were in the anticipated di-rections. Although the significant Q-statistics indi-cated that there were between-study moderators forrelationships between politics and nonperfor-mance outcomes, these moderators were likely toaffect only the magnitude, rather than the direction,of the relationships, as the credibility interval ex-cluded zero.

Proximal outcomes. The sample-weighted meancorrelation between perceptions of organizationalpolitics and strain was .39. Sampling and measure-ment error accounted for 16 percent of the variancein correlations. After correcting for sampling andmeasurement error, the population correlation was.48. The Q was significant. However, the three be-tween-study moderators that were tested did notaccount for differences between effect sizes, as thesubgroup analysis yielded nonsignificant results.The sample-weighted mean correlation betweenperceptions of organizational politics and job satis-faction was �.47. After correction for sampling er-

ror and measurement unreliability, which ac-counted for 21 percent of the variance incorrelations, the population correlation estimatewas �.57. Unpublished studies yielded larger ef-fect sizes (� � �.61) than published studies (� ��.57; Z � �2.87, p � .01), and U.S. samples re-sponded more negatively to perceptions of organi-zational politics (� � �.58) than Israeli samples(� � �.46; Z � 5.93, p � .001). Similarly, affectivecommitment had a sample-weighted mean correla-tion coefficient of �.43 with perceptions of organ-izational politics. Sampling error and measurementunreliability accounted for 14 percent of the vari-ance in the correlations between perceptions oforganizational politics and commitment, and thecorrected population correlation was �.54. The un-published studies also had larger effect sizes (� ��.62) than the published studies (� � �.52; Z ��6.35, p � .001), and perceptions of organizationalpolitics were more strongly related to commitmentin U.S. samples (� � �.56) than in Israeli samples(� � �.34; Z � 9.81, p � .001).

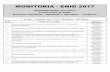

TABLE 1Meta-analytic Correlations between Perceptions of Organizational Politics, Strain, Morale, and Performancea, b

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1. Perceptions of organizational politics2. Strain .48b

k 21N 7,140

3. Job satisfaction �.57c �.45i

k 45 72N 16,640 22,106

4. Affective commitment �.54d �.31j .68o

k 33 32 36N 11,633 10,808 12,269

5. Task performance �.20e �.21k .30p .18t

k 14 30 242 87N 3,397 6,769 44,518 20,973

6. OCB, individual �.16f �.23l .26q .25u .66x

k 9 15 22 42 14N 1,913 5,194 5,549 10,747 4,831

7. OCB, organization �.20g �.25m .24r .25v .72y .72aa

k 9 16 20 42 13 44N 1,913 3,893 5,189 10,747 4,958 10,647

8. Turnover intentions .43h .31n �.58s �.58w �.16z �.21ab �.22ac

k 27 63 70 97 38 7 7N 8,439 21,056 23,603 41,002 7,643 1,344 1,344

a All correlations were corrected for attenuation due to unreliability. If more than one study reported on the same relationship, we usedthe estimate reflecting the greatest amount of data (in most cases, it was the most recent data). “k” is the number of effect sizes; N is totalobservations.

b The letter superscripts in the body of the table indicate the source of the meta-analytic correlations as follows: “i,” “j,” “n,” “o,” “s,”Podsakoff, LePine, and LePine (2007); “k,” LePine, Podsakoff, and LePine (2005); “l,” “m,” Matias, Chang, and Johnson (2007); “p” Judge,Thoresen, Bono, and Patton (2001); “q,” “r,” Organ and Ryan (1995); “t,” “u,” “v,” Harrison, Newman, and Roth (2006); “w,” Cooper-Hakinand Viswasvaran (2005); “x,” “y,” “aa,” Hoffman, Blair, Meriac, and Woehr (2007); “z,” Zimmerman and Darnold (2009).

Original analyses in the current paper include “b,” “c,” “d,” “e,” “f,” “g,” “h,” “ab,” and “ac.” Detailed information for relationships “b”through “h” can be found in Table 2. For more detailed results for relationships “ab” and “ac,” please contact the first author.

2009 787Chang, Rosen, and Levy

TABLE 2Meta-analytic Results for Bivariate Relationships between Perceptions of Organizational Politics and

Outcome Variablesa

Variables and Moderators k N r � s.d.� %s.e.

95% CI 95% CV

Q ZLower Upper Lower Upper

StrainOverall 21 7,140 .39 .48 .15 11.99 .34 .45 .19 .76 130.99***Publication status 0.34

Unpublished studies 3 742 .40 .49 .10 27.50 .30 .52 .29 .69 10.41**Published studies 18 6,398 .39 .48 .15 10.99 .33 .46 .18 .77 117.48***

Sample 0.43Employed student samples 5 1,135 .37 .46 .09 35.59 .29 .46 .28 .63 11.82*Employee samples 16 6,005 .40 .48 .15 9.94 .33 .47 .18 .78 117.91***

Country 0.77Israel 3 541 .39 .50 .01 91.45 .32 .46 .48 .51 3.01United States 15 5,676 .40 .49 .16 9.44 .33 .48 .18 .79 115.59***

Job satisfactionOverall 45 16,640 �.47 �.57 .13 11.23 �.51 �.44 �.83 �.32 218.98***Publication status �2.87**

Unpublished studies 7 2,597 �.50 �.61 .08 19.05 �.57 �.44 �.77 �.46 14.21*Published studies 38 14,043 �.46 �.57 .14 10.68 �.50 �.43 �.84 �.30 211.70***

Sample 0.52Employed student samples 8 1,861 �.46 �.54 .00 84.68 �.50 �.42 �.54 �.54 7.83Employee samples 37 14,779 �.47 �.58 .14 9.44 �.51 �.43 �.86 �.31 198.48***

Country 5.93***Israel 7 1,414 �.35 �.46 .06 54.03 �.41 �.28 �.60 �.33 11.30United States 35 14,671 �.48 �.58 .13 10.43 �.52 �.44 �.82 �.33 203.04***

Affective commitmentOverall 33 11,633 �.43 �.54 .16 13.58 �.47 �.38 �.86 �.22 243.00***Publication status �6.35***

Unpublished studies 5 2,271 �.50 �.62 .11 13.67 �.59 �.42 �.83 �.41 30.47***Published studies 28 9,362 �.41 �.52 .17 10.49 �.46 �.36 �.84 �.19 199.59***

Sample 1.01Employed student samples 6 1,525 �.42 �.52 .05 57.30 �.46 �.38 �.62 �.41 10.06Employee samples 27 10,108 �.43 �.54 .17 8.38 �.48 �.37 �.88 �.20 219.54***

Country 9.81***Israel 7 1,414 �.26 �.34 .11 38.13 �.34 �.18 �.55 �.13 17.37*US 26 10,219 �.45 �.56 .15 10.14 �.50 �.40 �.85 �.27 176.64***

Turnover intentionsOverall 27 8,439 .36 .43 .11 20.28 .32 .40 .21 .66 110.45***Publication status 1.78

Unpublished studies 3 895 .40 .48 .03 75.05 .35 .46 .42 .54 3.69Published studies 24 7,544 .36 .43 .12 19.07 .31 .40 .19 .66 103.63***

Sample 1.54Employed student samples 4 1,080 .38 .47 .04 60.61 .33 .44 .39 .56 5.36Employee samples 23 7,359 .36 .43 .12 18.38 .31 .40 .19 .66 100.08***

Task performanceOverall 14 3,397 �.13 �.20 .07 63.63 �.16 �.09 �.34 �.05 21.81

OCB, individualOverall 9 1,913 �.14 �.16 .03 95.11 �.18 �.09 �.20 �.13 9.37

OCB, organizationOverall 9 1,913 �.16 �.20 .00 100.00 �.20 �.12 �.20 �.20 7.57

a k is the number of effect sizes; N is the total number of subjects; r is the mean sample-weighted correlation; � is the estimate of the fullycorrected population correlation; s.d.� is the standard deviation of the estimate of the fully corrected population correlation; %s.e. is thepercentage of observed variance accounted for by sampling and measurement error; 95% CI is the 95% confidence interval aroundthe mean sample-weighted correlation; 95% CV is the 95% credibility interval around the corrected mean population correlation; Qis the chi-square test for the homogeneity of true correlations across studies; and Z is the test for the significance of the differencebetween the sample-weighted correlations.

* p � .05** p � .01

*** p � .001

788 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

Distal outcomes. The sample-weighted meancorrelation between perceptions of organizationalpolitics and turnover intentions was .36. After cor-recting for sampling and measurement artifacts,which explained 24 percent of the variance in cor-relations, the estimated population correlation was.43. Because of the significant Q, we tested forbetween-study moderators and found that neitherpublication status nor sample type moderated themagnitude of this relationship. This result sup-ported Hypothesis 3. The sample-weighted meancorrelation between perceptions of organizationalpolitics and task performance was �.13. Samplingerror and measurement unreliability accounted for64 percent of the variance in observed correlationsacross studies. The corrected population correla-tion was �.20. For the relationship between per-ceptions of organizational politics and OCB towardindividuals (OCBI), the sample-weighted mean cor-relation was �.14, and the corrected populationcorrelation was �.16. Sampling error and measure-ment unreliability accounted for 86 percent of thevariance observed in correlations. The sample-weighted mean correlation between perceptions oforganizational politics and OCB toward one’s or-ganization (OCBO) was �.16, the corrected popu-lation correlation was �.20, and sampling error andmeasurement unreliability accounted for 100 per-cent of the variance observed in these correlations.Thus, perceptions of organizational politics hadnegative relationships with all three supervisor-rated performance measures, which supported Hy-pothesis 4. Additionally, none of the 95% credibil-ity intervals included zero, and all threeQ-statistics were nonsignificant, indicating that themagnitudes of these relationships were not affectedby between-study moderators.

Model Testing

To test the proposed model, we first created la-tent constructs to represent morale and job perfor-mance. Job satisfaction and affective commitmentserved as indicators of morale. The job performanceconstruct included task performance, OCBI, andOCBO as indicators. To evaluate these latent con-structs, we conducted a confirmatory factor analy-sis (CFA) using maximum likelihood estimation inMplus 4.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 2005). The followingcriteria were used to assess model fit: comparativefit (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis (TLI) index valuesgreater than .90, a root-mean-square error of ap-proximation (RMSEA) of less than .06, and a stan-dardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) of less

than .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The overall measure-ment model had reasonably good fit to the data(CFI � .98, TLI � .94, RMSEA � .12, SRMR � .02).

We then tested the proposed model in whicheffects of perceptions of organizational politics onturnover intentions and job performance were fullymediated by strain and morale. As reported in Ta-ble 3, the model fit the data (CFI � .97, TLI � .94,RMSEA � .09, SRMR � .02), and all paths weresignificant, except for the path linking strain toturnover intentions (� � �.02). We then tested forpartial mediation effects by including direct pathsfrom perceptions of organizational politics to thetwo distal outcome variables in the next three al-ternative models (see Figure 1). As reported in Ta-ble 3, the three alternative models had essentiallythe same fit indexes as the theoretical model. Fur-ther analyses revealed that adding a path betweenperceptions of organizational politics and turnoverintentions (alternative model 1: ��2

1 � 0.59, n.s.),or between politics and performance (alternativemodel 2: ��2

1 � 1.24, n.s.) did not improve modelfit over that of the theoretical model. When bothpaths were freely estimated (alternative model 3:��2

2 � 2.35, n.s.), none of the direct paths weresignificant, nor did model fit improve significantly.Thus, the theoretical model received support, andthe results provided evidence that strain and mo-rale fully mediated the effects of perceptions oforganizational politics on performance and turn-over intentions.

As shown in Figure 3, perceptions of organiza-tional politics were associated with increased psy-chological strain (� � .48, p � .05), supportingHypothesis 1. Supporting Hypothesis 2, percep-tions of organizational politics were related to mo-rale both directly (� � �.57, p � .05) and indirectlythrough strain (� � �.20, p � .05). In terms ofmediation effects, we found support for Hypothesis5b: effects of morale fully mediated perceptions oforganizational politics on turnover intentions (� ��.70, p � .05). Hypothesis 5a was supported by amore extended mediational chain; higher percep-tions of organizational politics were associatedwith increased strain and then reduced morale,which in turn related to increased turnover inten-tions. Supporting Hypothesis 6, the relationshipbetween perceptions of organizational politics andperformance was fully mediated by both strain (� ��.14, p � .05) and morale (� � .28, p � .05).Overall, our results demonstrated that strain andmorale fully mediated the effects of perceptions oforganizational politics on turnover intentions andperformance.

2009 789Chang, Rosen, and Levy

Perceptions of Organizational Politics, RoleAmbiguity, and Role Conflict

To explore the distinctiveness of perceptions oforganizational politics from other hindrance stres-sors, we first compared the bivariate meta-analyticestimates of relationships between politics, roleconflict, and role ambiguity, and between thesestressors and outcome variables (see Table 4). Per-ceptions of organizational politics had a strongerrelationship with role conflict than with role ambi-guity (� � .58 vs. .52, Z � �3.04, p � .001). Forstressor-outcome relationships, perceptions of or-ganizational politics had significantly stronger as-sociations with strain, job satisfaction, affectivecommitment, and OCB0, than role ambiguity. Ad-ditionally, the perceptions of organizational poli-tics–outcome relationships were significantlystronger than role conflict–outcome relationships

for almost all the variables except for strain, OCB1,and turnover intentions. These results indicate thatperceptions of organizational politics had differentrelationships with role stressors, and that percep-tions of organizational politics–outcome relation-ships were typically stronger, if not comparable, tothe role stressor–outcome relationships.

Next, we explored two different conceptualiza-tions of the hindrance stressor construct within thecontext of the proposed model (Figure 2). Table 3summarizes the results of these nested model tests.The diversified model had better fit (��2

4 � 196.32,p � .001) than the unified model (CFI � .94, TLI �.90, RMSEA � .10, SRMR � .03), suggesting thatperceptions of organizational politics and rolestressors are best viewed as distinct yet relatedstressors. We also evaluated possible partial medi-ation effects (see Table 3). Although the effects of

TABLE 3Fit Statistics for Alternative Models

Model �2 df CFI TLI RMSEA SRMR ��2

Perceptions of organizational politics as theonly predictor a

Theoretical 587.00 15 .97 .94 .09 .02Alternative model 1b 586.41 14 .97 .94 .09 .02 0.59e

Alternative model 2c 585.76 14 .97 .95 .08 .02 1.24e

Alternative model 3d 584.45 13 .97 .95 .08 .02 2.35e

Two conceptualizations of hindrance stressor f

Unified hindrance stressor 1,526.87 29 .94 .90 .10 .03Diversified hindrance stressors: Perceptions

of organizational politics, roleambiguity, and role conflict

1,333.76 25 .93 .89 .10 .03 193.11k***

Alternative model 4g 1,332.60 23 .93 .88 .11 .03 1.16l

Alternative model 5h 1,266.28 23 .94 .89 .11 .02 67.48l***Alternative model 6i 1,270.00 24 .94 .89 .10 .03 3.72m

Alternative model 7j 1,128.11 22 .94 .89 .10 .03 141.89n***

a CFI � comparative fit index; TLI � Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA � root-mean-square error of approximation; SRMR � standardizedroot-mean-square residual. N � 5,160.

b Estimate of the direct effect from perceptions of organizational politics to turnover intentions with other paths held constant.c Estimate of the direct effect from perceptions of organizational politics to performance with other paths held constant.d Estimate of the direct effects from perceptions of organizational politics to distal outcomes with other paths held constant.e Model fit compared with the theoretical model.f N � 4,865.g Estimate of the direct effects from perceptions of organizational politics to distal outcomes with other paths held constant.h Estimate of the direct effects from role ambiguity to distal outcomes with other paths held constant.i Estimate of the direct effects from role ambiguity to turnover intentions with other paths held constant.j Estimate of the direct effects from role ambiguity to turnover intentions and role conflict to distal outcomes with other paths held

constant.k Model fit compared with the unified hindrance stressor model.l Model fit compared with the diversified hindrance stressors model.m Model fit compared with alternative model 5.n Model fit compared with alternative model 6.

* p � .05** p � .01

*** p � .001

790 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

perceptions of organizational politics on the twodistal outcomes appeared to be fully mediated (al-ternative model 4: ��2

2 � 1.16, n.s.), the effects ofrole ambiguity were partially mediated (alternativemodel 5: ��2

2 � 67.48, p � .001). However, onlythe direct path from role ambiguity to turnoverintentions was significant. Thus, we dropped theother direct path from the model, which did notimpact the model fit (alternative model 6: ��2

1 �3.72, n.s.). Finally, we added paths from role con-flict to both outcomes, and both paths were signif-icant. This final model (Figure 4) showed improve-ment in fit over alternative model 6 (��2

2 � 141.89,p � .001) and included three direct paths from roleambiguity and role conflict to distal outcomes.

Perceptions of organizational politics (� � .18),role ambiguity (� � .20), and role conflict (� � .33)each had significant, positive relationships with

strain. The 95% confidence intervals for the effectsof politics and role ambiguity overlapped, but roleconflict had the strongest association with strain.Paths from perceptions of organizational politics(� � �.43), role ambiguity (� � �.22), and roleconflict (� � �.09) to morale were all significant.None of their confidence intervals overlapped, in-dicating that the politics-morale link was strongerthan the other two links. In addition, though strainand morale fully mediated the effects of percep-tions of organizational politics on distal outcomes,role ambiguity had a direct link with turnover in-tentions (� � .10), and role conflict had directassociations with turnover intentions (� � .16) andperformance (� � �.06). Overall, these significantdifferences in path coefficients and distinct pat-terns of mediation effects help distinguish percep-tions of organizational politics from role stressors.

FIGURE 3Final Model of Effects of Perceptions of Organizational Politics on Employee Outcomesa

a All path coefficients and loadings are significant at p � .05 except for the italicized coefficient, for which p � .05; numbers inparentheses represent the lower and upper bounds for the 95% confidence interval for path coefficients.

2009 791Chang, Rosen, and Levy

DISCUSSION

The current research had three goals: (1) to ad-dress inconsistencies in the research findings onperceptions of organizational politics, (2) to exam-ine a model that incorporated stress and socialexchange explanations of reactions to perceptionsof organizational politics, and (3) to explorewhether perceptions of organizational politics were

distinguishable from other role-based hindrancestressors. In keeping with Miller et al.’s (2008)meta-analysis of the outcomes of perceptions oforganizational politics, the results of the currentstudy demonstrated that such perceptions havestrong, positive relationships with strain and turn-over intentions and strong, negative relationshipswith job satisfaction and affective commitment.However, the current study extends previous re-search by providing unequivocal support for a re-lationship between perceptions of organizationalpolitics and aspects of job performance that werenot clearly supported (viz., task performance) ortested (viz., OCB) in Miller et al.’s (2008) meta-analysis.

Beyond the basic bivariate estimates, our resultsalso provided compelling evidence supporting atheoretically derived model that integrates thestress- and social exchange–based explanations ofthe effects of perceptions of organizational politics.In particular, perceptions of organizational politicswere associated with increased psychologicalstrain, which was associated directly with reducedperformance, as well as indirectly with increasedturnover intentions through reduced morale. Polit-ical perceptions also had a direct, negative linkwith employee morale, which was related to in-creased turnover intentions and reduced perfor-mance. These findings revealed that strain and mo-rale fully mediate the effects of perceptions oforganizational politics on important employee re-actions. In addition, they indicated that the stressand social exchange perspectives complement eachother. Thus, simultaneously considering the medi-ating effects of morale and strain provides a morecomplete picture of the intrapersonal processesthat relate perceptions of organizational politics todistal employee outcomes.

Interestingly, results of the exploratory analysessuggested that political perceptions are distinctfrom at least two other hindrance stressors––roleambiguity and role conflict. Perceptions of organi-zational politics had different relationships withthose role stressors. Also, bivariate relationshipsbetween political perceptions and outcomes werealmost always stronger than or comparable with therole stressor–outcome relationships. Finally, whenconsidered together, perceived politics had aunique pattern of associations with employee out-comes: the effects of perceptions of organizationalpolitics on distal outcomes were fully mediated bystrain and morale, whereas the effects of role stres-sors on distal outcomes were only partiallymediated.

TABLE 4Comparison of Meta-analytic Relationships among

Hindrance Stressors and between Hindrance Stressorsand Employee Attitudes and Behaviorsa

Outcome and HindranceStressors � k N Z

Perceptions of organizationalpolitics

Role ambiguityb .52 6 3,504Role conflictb .58 4 1,941 �3.04***

StrainPerceptions of organizational

politics.48 21 7,140

Role ambiguityc .43 8 1,435 2.05*Role conflictc .52 7 1,220 �1.84

Job satisfactionPerceptions of organizational

politics�.57 45 16,640

Role ambiguityc �.48 42 10,062 �10.34***Role conflictc �.49 39 9,780 �9.23***

Affective commitmentPerceptions of organizational

politics�.54 33 11,633

Role ambiguityc �.39 12 3,774 �10.07***Role conflictc �.30 9 3,225 �12.94***

Task performancePerceptions of organizational

politics�.20 14 3,397

Role ambiguityc �.22 18 4,301 1.05Role conflictc �.14 16 4,057 �2.66**

OCB, individualPerceptions of organizational

politics�.16 9 1,913

Role ambiguityd �.16 10 2,651 0.00Role conflictd �.15 7 2,351 �0.33

OCB, organizationPerceptions of organizational

politics�.20 9 1,913

Role ambiguityd �.12 7 2,456 �2.69***Role conflictd �.14 6 2,156 �1.97*

Turnover intentionsPerceptions of organizational

politics.43 27 8,439

Role ambiguityc .44 8 1,188 �0.29Role conflictc .45 8 1,188 �0.53

a The letter superscripts in the body of the table indicate thesource of the meta-analytic correlations as follows: “b,” currentstudy; “c,” Ortqvist and Wincent (2006); “d,” Podsakoff, Mac-Kenzie, and Bommer (1996).

* p � .05** p � .01

*** p � .001

792 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

Theoretical Implications

This research offers a number of important theo-retical contributions. First, the significant relation-ships between perceptions of organizational poli-tics and the focal outcomes (i.e., psychologicalstrain, morale, turnover intentions, and perfor-mance) provide additional support for the notionthat, in response to perceptions of organizationalpolitics, employees are likely to withdraw from anorganization in order to avoid political “games.”Moreover, our findings clearly linked perceptionsof organizational politics with task performanceand OCB, indicating that, overall, perceived poli-tics represent an aversive aspect of the work envi-ronment. These findings also counter theoreticalarguments (see Ferris et al., 1989; Ferris & Kacmar,1992) suggesting that employees may respond toperceptions of organizational politics by immersing

themselves in their work or by increasing the extentto which they are involved in their jobs. Similarly,our findings suggest that previous studies showingpositive associations between perceptions of organ-izational politics and desirable outcomes (e.g., Fer-ris et al., 1993; Ferris & Kacmar, 1992) representexceptions in the literature and may be due tostatistical artifacts. In general, employee percep-tions of self-serving, illegitimate political activitiesat work have consistently negative relationshipswith employee attitudes and behaviors.

Regarding the moderator analyses, we found lit-tle evidence for publication bias (Rosenthal, 1979),as unpublished studies had either stronger effectsizes than published ones, or comparable effectsizes. In addition, effect sizes from studies withemployed students were similar to those from stud-ies with full-time employees. This pattern sug-

FIGURE 4Final Model of Effects of Perceptions of Organizational Politics, Role Ambiguity, and Role Conflict on

Employee Outcomesa

a All path coefficients and loadings are significant at p � .05, except for the italicized coefficient, for which p � .05; numbers inparentheses represent the lower and upper bounds for the 95% confidence interval for path coefficients.

2009 793Chang, Rosen, and Levy

gested that the employment relationships that de-velop between employed students and theiremployers may be as meaningful and important asrelationships that develop between full-time em-ployees and their organizations and that percep-tions of organizational politics have similar impli-cations for both groups.

However, we did observe cross-cultural differ-ences between U.S. and Israeli samples, in thatperceptions of organizational politics had strongerrelationships with morale for U.S. employees. Thispattern is consistent with Vigoda’s (2001) proposi-tion that, because of their experiences with geopo-litical conflict, Israeli employees are better condi-tioned for coping with the interpersonal conflictassociated with organizational politics. Similarly,Romm and Drory (1988) suggested that Israelishave greater familiarity with political processes in-side work and outside of work, which may be as-sociated with (1) greater tolerance for political ac-tivities as a means of getting ahead and (2) a beliefthat organizational politics are normative and mor-ally legitimate. These ideas are consistent with thenotion that national culture influences the mentalprograms that guide employees’ interpretations andreactions to different aspects of their jobs (Hof-stede, 1980). As such, these cross-cultural differ-ences may contribute to understanding of the gen-eralizability of theories linking perceptions oforganizational politics to employee outcomes. Forexample, our findings imply that U.S. and Israeliemployees may have different expectations thatguide the evaluations of their organizational ex-change relationships. Thus, to the extent that lowlevels of politics are central to employees’ workexpectations, perceptions of organizational politicswill be salient and represent a more serious viola-tion of their social exchange relationships. How-ever, additional research is necessary to determinewhether differences in exchange expectations ac-count for cross-cultural disparities in relationshipsbetween perceptions of organizational politics andmorale.

Another contribution of this study is that it sub-stantiated our arguments that multiple pathwayslink perceptions of organizational politics to em-ployee outcomes. Model-testing results demon-strate that mediators proposed by work stress (i.e.,job anxiety) and social exchange (i.e., morale) the-ories explain relationships between politics andboth performance and withdrawal intentions.These findings were supportive of theory and pro-vided evidence that both perspectives contribute tounderstanding of how social context affects atti-tudes and behaviors. Additionally, our resultshighlight the importance of considering alternative

ways of arranging the outcomes of perceptions oforganizational politics that go beyond treating themall as direct outcomes, as has been implied by pre-vious research (e.g., Ferris et al., 2002; Miller et al.,2008). Interestingly, the effects of perceptions oforganizational politics on turnover intentions andperformance worked through slightly differentpathways. In particular, the psychological strainelicited by perceptions of organizational politicswas associated with decreased morale, which wasrelated to higher turnover intent. This pattern im-plies that the effects of perceptions of organization-al politics on turnover intentions may take longerto unfold and may involve a more rational process.Turnover researchers have conceptualized the typ-ical voluntary turnover process as initiated by lowmorale and involving multiple decision points(Griffeth, Hom, & Gartner, 2000). An alternativeviewpoint, the unfolding model of turnover (Lee &Mitchell, 1994), suggests that a new situation orevent, in addition to morale, triggers employeeturnover. However, according to this model, em-ployees may still follow extensive decision-makingpaths leading to turnover, and three out of the fourproposed paths involve job satisfaction. Thus, ourresults are consistent with previous work concern-ing the formulation of turnover intentions. They arealso consistent with other studies (e.g., Podsakoff etal., 2007) in demonstrating that the effects of hin-drance stressors on turnover intentions work firstthrough strain and then through morale.

On the other hand, the effect of perceptions oforganizational politics on performance workedthrough both strain and morale simultaneously.The pathway through strain coincides with theo-ries suggesting that strain and other negative affec-tive experiences have an impact on motivation andperformance (Lord & Kanfer, 2002). For example,the resource allocation perspective (Kanfer & Ack-erman, 1989) implies that strain drains mental re-sources that could otherwise be devoted to self-regulatory activities associated with jobperformance. According to Kanfer and Ackerman,self-regulatory activities, such as goal striving andfeedback monitoring, require effortful processingand mental resources. As employees experiencestrain associated with perceptions of organizationalpolitics, they may devote energy to coping withtheir negative affect, thereby reducing the resourcesthey can spare for regulating performance. In addi-tion, perceptions of organizational politics wereassociated with lower morale, which led to reducedjob performance. Our results imply that, as a resultof perceiving politics, employees may begin toview their organizations as risky investments and

794 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

may demonstrate lower levels of morale, and alsodecrease their contributions to their jobs.

Finally, the results of exploratory analysesshowed that perceptions of organizational politicsare distinct from both role ambiguity and role con-flict. In addition to the stronger bivariate correla-tions with outcomes demonstrated by political per-ceptions, the mechanisms underlying the effects ofperceptions of organizational politics on turnoverintentions and performance were dissimilar tothose underlying the effects of role stressors. Thesefindings point to the possibility that perceptions oforganizational politics may be qualitatively differ-ent from role-based hindrance stressors. In partic-ular, perceptions of organizational politics repre-sent evaluations of social aspects of organizationalsettings (i.e., witnessing members politicking andreceiving rewards), rather than the assessments ofpersonal situations (i.e., comparing individuals’ jobdemands to their coping resources) that character-ize role stressors (Boswell et al., 2004). In addition,employees experience role ambiguity and conflictbecause they are concerned with fulfilling theirroles as stipulated by their organization, whereasperceptions of organizational politics are associ-ated with observing behaviors that are self-servingand threatening to the well-being of other employ-ees (Kacmar & Baron, 1999). Thus, although per-ceived politics had seemingly similar effects onoutcomes as the broadly defined hindrance stressorconstruct examined in previous studies (e.g.,LePine et al., 2005; Podsakoff et al., 2007), thesimilar effects may be attributable to perceptions oforganizational politics serving as the dominant in-dicator of the unified hindrance stressor construct,thereby driving the effects of the construct. Thus,future studies should explore whether (and when)it is appropriate to consider perceptions of organi-zational politics separately from other hindrancestressors. For example, if the goal of research is topredict general work attitudes and behaviors, thenit may be prudent to conceptualize perceptions oforganizational politics and role stressors as part ofthe unified, general hindrance stressor construct.This approach is akin to considering differentforms of justice (viz., distributive, procedural, in-terpersonal, and informational) as indicators of anoverall justice evaluation (see Ambrose &Schminke, 2006). However, if the goal of a study isto understand more specifically how the interplaybetween these stressors (e.g., the effects of percep-tions of organizational politics may work throughrole ambiguity, or role ambiguity may exacerbateeffects of such perceptions) relates to employeeoutcomes, then researchers may want to considerthese hindrance stressors separately to capture

their unique effects. Moreover, unlike the effects ofperceptions of politics, the effects of role stressorson turnover intentions and performance were notcompletely accounted for by the stress- and socialexchange–based paths, which suggests that addi-tional mediating mechanisms explain the effects ofrole stressors, but not those of perceptions of organ-izational politics.

Managerial Implications

Our results have several practical implications.First, leaders should recognize that, though somepolitical activities may be essential to the function-ing of work groups (Fedor et al., 2008), their ownpolitical activities may have unanticipated con-sequences at the individual level. For instance,leaders often make “idiosyncratic deals” withemployees as a means of optimizing individualperformance and reducing turnover (Rousseau, Ho,& Greenberg, 2006). The current research demon-strates that if these activities are perceived as po-litical (i.e., based on favoritism and self-interest),then they may have extensive negative effects onorganization members. Therefore, it is importantfor top management to make decisions that balancethe costs and benefits of engaging in behaviors thatmay be perceived as political.

Next, we demonstrated that employees respondnegatively to work conditions that indicate politics.Thus, it behooves managers to focus on social con-text when attempting to understand employee atti-tudes and motivation. For example, managers mayreduce perceptions of organizational politics andsubsequent deficits in morale and motivation byproviding clear feedback regarding which behav-iors their organization desires (Rosen et al., 2006),by reducing incentives for employees to engage inpolitical activities, or by aligning individual andorganizational goals (see Witt, 1998). In extremesituations, it may benefit an organization to targetkey political players whose activities are especiallysalient and damaging. If these individuals are notwilling to reduce their political activities, then theyshould be removed from the organization. Al-though extreme, such tactics may benefit employeehealth and performance in the long run.

Asking managers to monitor and reduce theirown political activities may not always be a realis-tic solution, and firing employees for being toopolitical may carry some risk in today’s litigioussociety. Therefore, we recommend that human re-source departments actively create competencymodels (see Shippmann et al., 2000) that incorpo-rate the goals of discouraging political activities

2009 795Chang, Rosen, and Levy

and providing incentives to managers for creatingwork environments that are not political. To beeffective, such programs must (1) show a relation-ship between organizational politics and individ-ual and organizational effectiveness, (2) identifycompetencies linked to organizational politics (e.g.,teamwork, decision making, conflict management),(3) define behavioral anchors of these competen-cies that are focused on reducing politics in thework environment (an example of such an anchorfor teamwork: “Is inclusive of all group memberswhen doing team projects”; for decision-making:“Follows corporate policies when making employ-ment decisions”), and (4) make employees account-able for these activities. Incorporating politics-based competencies into performance managementprograms will provide a mechanism for document-ing behaviors, providing feedback, setting develop-mental goals, and substantiating employment deci-sions. As such, a competency-based approach tomanaging organizational politics benefits an organ-ization by creating a positive social climate thatminimizes incentives for politicking and providinga mechanism for documenting employment deci-sions, which will protect the organization if it musttake action against overly political employees.

Finally, our results suggest that leaders may beable to counter the effects of politics and role stres-sors by targeting intervening processes. For exam-ple, organizations may benefit from stress manage-ment interventions, such as training employees ineffective conflict resolution and time managementskills and adopting flexible work arrangements toalleviate psychological strain. Doing so will free upcoping resources, improving the ability of employ-ees to deal with demands placed on them by polit-ical aspects of their jobs or allowing them to clarifytheir role requirements. Alternatively, by commu-nicating that employees are valued, supervisorsmay be able to improve employee exchange percep-tions and subsequent attitudes. This strategy maybe helpful in battling against the effects of percep-tions of organizational politics, yet it may be lesseffective in dealing with role stressors, which haveweaker associations with exchange-related atti-tudes. Instead, organizations may benefit from pro-viding employees with regular, high-quality feed-back to facilitate role definition processes(Schaubroeck, Ganster, Sime, & Ditman, 1993),thereby reducing the effects of role stressors. Thus,depending on the stressor that is most prevalent,leaders should adopt different strategies for mini-mizing the effects of perceptions of organizationalpolitics and role stressors.

Limitations and Future Research

Some researchers have questioned the appropri-ateness of using correlation matrixes derived frommeta-analysis for SEM. For instance, it has beenargued that these analyses bias model fit indexesand path estimates (Cheung & Chan, 2005). In ad-dition, the quality of the primary studies, as well asthe procedures and corrections adopted in differentmeta-analyses, may influence model fit and pathestimates (e.g., Arthur et al., 2001). However,model testing in the current study was grounded intheory and represented an initial effort to examinea complex, integrated model of psychological pro-cesses that relate perceptions of organizational pol-itics to outcomes. Nonetheless, we recommend thatothers view our findings as a first step towardbuilding a model that explains how perceptions oforganizational politics are related to employeeoutcomes.

One possible way to extend the current findingsis to examine explanations of the effects of percep-tions of organizational politics based on stress andsocial exchange using more diverse and, when ap-propriate, more direct measures of these constructs.For example, other strain responses (e.g., physicalsymptoms) could be used to evaluate the strain-based pathway through which organizational poli-tics perceptions relate to employee outcomes. Also,the current study used morale as a proxy measureof employee perceptions of the exchange relation-ship. Measures of psychological contract breachrepresent more direct assessment of exchange qual-ity. Thus, future studies should employ these alter-native measures to replicate and extend the modeltested in the current study.

In addition, future research should identify mod-erators of the effects of perceptions of organization-al politics and role stressors. Some moderators maybe universal and attenuate the effects of both polit-ical perceptions and role stressors. For example,situational factors such as support (Bliese & Castro,2000) and control (Ferris et al., 1989) and individ-ual differences such as psychological hardiness(Kobasa, 1979) may help alleviate the negative im-pact of perceptions of organizational politics androle stressors on strain. Other variables may showmore selective moderation effects. For example,self-monitoring (Rosen, Chang, & Levy, 2006) maybuffer the effects of perceptions of organizationalpolitics, although the moderating influences of rolesalience (Noor, 2004) may be more specific to rolestressor–outcome relationships. Identifying andtesting these specific moderators will help furtherdistinguish between perceptions of organizationalpolitics and role stressors.

796 AugustAcademy of Management Journal

Finally, a potential threat to the validity of ourfindings is common method bias (Podsakoff, MacK-enzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). In the current study,relationships between predictors, mediators, andone of the outcome variables (turnover intentions)were based on measures collected from the samesource. Thus, we were unable to provide a defini-tive answer regarding the causal ordering of thesevariables. Thus, additional empirical studies areneeded to examine the pathways through whichperceptions of organizational politics influenceemployee outcomes, and researchers should mea-sure the political perceptions construct and its out-comes at different time points to establish temporalseparateness. Alternatively, other types of mea-sures (e.g., physiological strain reactions and actualturnover) could be used to establish the separate-ness of these constructs.