Disease and medicine ROBERT PECKHAM University of Hong Kong, China A major challenge for historians is the retro- spective diagnoses of diseases on the basis of recognizable symptoms. “Disease” is an equivocal term: in different historical and cul- tural settings diseases have been understood and described in very different ways. Chinese and Ayurvedic medical systems, for example, are organized on principles different from conventional Western nosology. Social cir- cumstances, cultural assumptions, and polit- ical institutions have also shaped the way diseases are interpreted and managed. Similar symptoms may be caused by different patho- logical agents, making diseases of the past problematic to identify. In Western biomedicine, human infectious diseases are understood as particular disor- ders caused by pathogenic micro-organisms, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi. While such diseases may be communi- cated from person to person, others may be transmitted to humans via animals or insects, or through the ingestion of contaminated foods and water. “Medicine” is understood as the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease, extending from clinical practice to sanitation and hygiene. Until the advent of germ theory in the 19th century, however, many infectious diseases were not recognized as such by physicians. Instead, their causes were attributed to an imbalance of the “humors”– the four vital fluids which made up the human constitution. While some dis- eases, notably leprosy and smallpox, were understood to be contagious, a wide variety of factors were educed to explain infection. According to “miasmic” theories, for exam- ple, disease was produced by the noxious emanations of decaying vegetable matter and filth. By linking territories in an often loose agglomeration, empires brought into contact divergent and often conflicting ideas about the nature and identity of disease. Studies of empire may thus furnish invaluable insights into “disease” as a comparative cultural phe- nomenon. By the same token, examining diverse responses to disease in the past may further our understanding of the processes that produced and underpinned empire. DISEASE AND ECOLOGIES OF EMPIRE Historically, empires created conditions for the emergence and diffusion of disease, just as disease events profoundly shaped imperial histories. The subjection of territories around the Mediterranean to imperial Roman rule from the first century BCE, greatly facilitated the spread of infections. It is likely, for exam- ple, that a “plague”– possibly of smallpox – brought to Rome from Mesopotamia during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE), compounded with internal conflicts to desta- bilize the imperium. The first recorded plague pandemic to afflict Europe, known as the Justinian Plague, occurred in the mid-6th century CE, when Constantinople was deva- stated. The historian Procopius, who lived through the pandemic, claimed that the dis- ease spread across the Mediterranean from the mouth of the Nile. In his History of the Wars (c.550), he described it in apocalyptic terms as a pestilence that threatened to erad- icate the human race. Evidence indicates that the accession of territories and the 1 The Encyclopedia of Empire, First Edition. Edited by John M. MacKenzie. © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Published 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe170

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Disease and medicineROBERT PECKHAM

University of Hong Kong, China

A major challenge for historians is the retro-spective diagnoses of diseases on the basisof recognizable symptoms. “Disease” is anequivocal term: in different historical and cul-tural settings diseases have been understoodand described in very different ways. Chineseand Ayurvedic medical systems, for example,are organized on principles different fromconventional Western nosology. Social cir-cumstances, cultural assumptions, and polit-ical institutions have also shaped the waydiseases are interpreted and managed. Similarsymptoms may be caused by different patho-logical agents, making diseases of the pastproblematic to identify.In Western biomedicine, human infectious

diseases are understood as particular disor-ders caused by pathogenic micro-organisms,including bacteria, viruses, parasites, andfungi. While such diseases may be communi-cated from person to person, others may betransmitted to humans via animals or insects,or through the ingestion of contaminatedfoods and water. “Medicine” is understoodas the diagnosis, treatment, and preventionof disease, extending from clinical practiceto sanitation and hygiene. Until the adventof germ theory in the 19th century, however,many infectious diseases were not recognizedas such by physicians. Instead, their causeswere attributed to an imbalance of the“humors” – the four vital fluids which madeup the human constitution. While some dis-eases, notably leprosy and smallpox, wereunderstood to be contagious, a wide varietyof factors were educed to explain infection.

According to “miasmic” theories, for exam-ple, disease was produced by the noxiousemanations of decaying vegetable matterand filth.By linking territories in an often loose

agglomeration, empires brought into contactdivergent and often conflicting ideas aboutthe nature and identity of disease. Studies ofempire may thus furnish invaluable insightsinto “disease” as a comparative cultural phe-nomenon. By the same token, examiningdiverse responses to disease in the past mayfurther our understanding of the processesthat produced and underpinned empire.

DISEASE AND ECOLOGIES OF EMPIRE

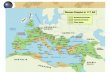

Historically, empires created conditions forthe emergence and diffusion of disease, justas disease events profoundly shaped imperialhistories. The subjection of territories aroundthe Mediterranean to imperial Roman rulefrom the first century BCE, greatly facilitatedthe spread of infections. It is likely, for exam-ple, that a “plague” – possibly of smallpox –brought to Rome from Mesopotamia duringthe reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE),compounded with internal conflicts to desta-bilize the imperium. The first recorded plaguepandemic to afflict Europe, known as theJustinian Plague, occurred in the mid-6thcentury CE, when Constantinople was deva-stated. The historian Procopius, who livedthrough the pandemic, claimed that the dis-ease spread across the Mediterranean fromthe mouth of the Nile. In his History of theWars (c.550), he described it in apocalypticterms as a pestilence that threatened to erad-icate the human race. Evidence indicatesthat the accession of territories and the

1

The Encyclopedia of Empire, First Edition. Edited by John M. MacKenzie.© 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Published 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.DOI: 10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe170

movement of troops, in conjunction withenvironmental transformations such asdeforestation, created conditions for diseasesto emerge, proliferate, and spread. Internalconflicts and pressures from without ampli-fied the disruptions caused by disease withconsequences for the coherence of the impe-rial order.The turbulence caused by the plague within

the Eastern Roman Empire may have played arole in precipitating the decline of the PersianSasanian Empire to the east, and was also alikely factor in the rise of the Arab Empireduring the 7th century. Following the estab-lishment of Islam in Arabia by the ProphetMuhammad (c.570–c.632 CE), large swathesof territory were conquered by the Arabsaround the Mediterranean. The UmayyadCaliphate, founded in 661, extended at itsapogee from present-day Iran to the Atlanticshores of the Iberian peninsula. In the initialphase of conquest, the traditional nomadicexistence of the Arab tribes may have sparedthem from the worse effects of infection.However, as the invading populations becameprogressively sedentarized, epidemics were topose increasing challenges. The experience ofdisease was to lead to the development of sci-entific and medical thinking, particularlyunder the Abbasids who seized power in750, when advances were made in a broadrange of medical areas, including anatomy,surgery, and hygiene. In the 11th century,the polymath scholar Ibn Sina (knownby his Latinized name Avicenna) compiledThe Canon of Medicine (1025), a medicalencyclopedia which describes the contagiousnature of certain diseases – as well as identi-fying their likely routes of transmission – andwhich became a prescribed medical text in theuniversities of Europe for centuries.Historians have conjectured that diseases

spread along the long-distance trade routesof the classical world, including the Silk Roadto Asia. In China, epidemics seem to have

been a contributory factor in the fall of theHan dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), acting as aspur to the development of Chinese medicalthinking. It was during this period that thephysician Zhang Ji (c.150–219 CE) compiledhis Treatise on Cold Damage and Miscellane-ous Disorders, examining the different clinicalmanifestations of “febrile epidemics,” thelikely climactic factors which he suggestedhad caused them, and appropriate treatments.However, given changing disease conceptsand the paucity of demographic evidence, itis impossible to determine with any certaintywhat microbial agents were responsible forthese epidemics and how severe they mayhave been.Trade across Eurasia certainly played an

important role in the transmission of bubonicplague in the medieval period. The establish-ment by Genghis Khan (c.1162–1227) of theMongol Empire – which at its furthest extentin the 13th century stretched from the Sea ofJapan to the borders of Europe – intensifiedthe traffic of peoples and commoditiesalong overland communication networks.Although the origins of the Black Death,which was to ravage much of Europe between1348 and 1350, continue to be debated, it hasbeen speculated that the extension of the car-avan trade under the PaxMongolica led to thediffusion of bubonic plague from the steppesof Mongolia to China, the Crimea, andfrom thence to Europe. Mongol conquestsmay have upset ecological and epidemio-logical balances, intermeshing disease poolswith momentous consequences for humansocieties.Evidence from a number of different impe-

rial contexts has thus underlined the roleplayed by proliferating imperial networksin the diffusion of disease. The extension ofthe Ottoman Empire (c.1299–1922) duringthe 15th and 16th centuries from the PersianGulf to the Atlantic, for example, appears tohave changed the epidemiology of disease

2

transmission. Expanding communicationand trade routes connecting the newly con-quered territories, as well as the growth ofcities, amplified and accelerated the spreadof disease, notably plague.Undoubtedly the most striking illustration

of the critical role of disease in the develop-ment of empire, however, is provided by theSpanish and Portuguese conquests of theAmericas from the end of the 15th century.In explaining how so few Europeans suc-ceeded in subjugating such large Aztec, Inca,and Mayan populations, historians havereasoned that disease was a decisive factor.Following Christopher Columbus’ secondexpedition to Hispaniola in 1493 – wherethe Spanish established their first colony inthe Americas – an epidemic of influenzaappears to have decimated the native Indianpopulation of the Antilles. Studies of theimpact of the Spanish conquest and coloniza-tion after 1518 on the populations of CentralMexico (New Spain) have suggested thatbetween the early 16th century and themid-17th century the indigenous populationfell by an estimated 90 percent. This implo-sion may be attributed in large part to theimportation of Old World infectious diseasesonto “virgin” soils, where there was noimmunity.The “discovery” of the Americas led to a

mingling of Old and New World plants, ani-mals, and micro-organisms in a process thathas been termed the Columbian Exchange.The migration of new species exposed indig-enous populations to novel pathogens,including smallpox, measles, chickenpox,typhus, and influenza. These were infectiousdiseases associated with the dense humanpopulations and domesticated animals ofthe Old World. The dramatic depletion ofindigenous populations as a result of theirlack of natural resistance to new diseases fun-damentally shifted the balance of power infavor of the Europeans.

The slave trade from West Africa to theAmericas and the Caribbean from the 16thcentury was also a crucial driver of disease,creating a lethal admixture of African, Euro-pean, and New World diseases, includingmalaria and yellow fever, both transmittedby mosquitoes. Some 12 million Africanslaves were transported to the New Worldby the Portuguese, British, French, Spanish,Dutch, and Americans. The vast majority ofslaves were brought to work on plantations.The institution of slavery became central tothe development of an imperial economicsystem based on commercial crops such assugar, as well as on gold and silver, and theproduction of goods bound for Europe. Dis-ease and empire were closely connected tothe growth of global capitalism and to theexpansion of a market economy supportedby new forms of production. During the Mid-dle Passage – the journey from Africa to theAmericas – slaves and crew were particularlysusceptible to infectious diseases, most com-monly dysentery. By one estimate some 1.5million died at sea, a statistic that does notinclude those who perished in the port fac-tories before embarkation or during the slaveraids, as well as those who died upon arrival.Biological and geographical explanations,

in addition to the development of technolo-gies such as firepower, may account for howEuropeans established empires with compar-ative ease, particularly in the Americas. Otherregions of the globe were also to experiencethe catastrophic consequences of virgin-soildiseases. In the Pacific, infections such asmeasles killed off many indigenous islanders.Following James Cook’s “discovery” ofHawaii in 1778, the native population mayhave plummeted by 90 percent. Similarly, asharp decline of the aboriginal populationof Australia occurred after settlement by theBritish in the late 18th century. The first out-break of smallpox in 1788–1789 may havekilled some 50 percent of the aboriginal

3

robertpeckham

Sticky Note

Marked set by robertpeckham

Sticky Note

Unmarked set by

population in Sydney. Comparative, globalperspectives on historical events thus under-score the importance of disease and relatedenvironmental factors in the formation ofempire in the modern period. They also dem-onstrate the degree to which empires them-selves may be thought of as ecologicalsystems, characterized by a complex interplayof politics, economics, and nature.Ecological approaches to world history

have increasingly gained popular currency.The historical dominance of Eurasian civili-zations, for example, has been ascribed toenvironmental variances: geography, accessto raw materials, and, crucially, disease, cre-ated specific advantages for Eurasians, settinginmotion a positive feedback loop. The exclu-sive focus on environment and disease ecol-ogy in such works, however, reflects anovertly deterministic approach to world his-tory, one in which the role of human agency,as well as social and cultural forces, may besidelined and sometimes even overlooked.At the same time, a racial theory of diseasesusceptibility and immunological deficiencyis perhaps inadvertently introduced. Theexclusive focus on immunity may downplaythe contributory roles of poverty, social dis-parity, and malnutrition, as well as consider-ation of the specific social and environmentalcontexts of mortality and morbidity.There are undoubtedly practical reasons

why the role of epidemics has been accentu-ated by historians since the archives oftencontain little information about less dramaticand more protracted conditions, such as diar-rheal infections – which continue to be amajor cause of mortality in the world today –or, for that matter, about non-communicableand endemic diseases. The exclusive focus ondisease crises may skew our perception of thepast, relegating other more constant anddebilitating but less conspicuous diseases tosubsidiary, “background” events. Notwith-standing these reservations, however, the

evidence strongly suggests that empire-building resulted in ecological changes withconsequences for disease emergence, whilethe mingling of populations and the creationof new trans-continental channels of inter-connection facilitated the spread of infection,creating an expanding global pool of disease.While the emphasis in imperial historio-

graphy tends to be on the epidemiologicalshock and calamitous demographic impactof imported diseases on indigenous popula-tions, colonizing societies (the metropole)were also affected by new diseases. Althoughthe existing evidence remains inconclusive,many historians have identified the GreatPox, which swept through much of Europein the 1490s, with the bacterial disease syph-ilis, contending that it was brought back toEurope from the New World. From the1820s, “Asiatic” cholera dispersed throughmuch of Europe and North America, killingmany thousands and precipitating far-reaching sanitary reforms. European settlers,colonial officials, and troops dispatchedoverseas to defend empire were themselvessusceptible to new diseases. Statistical ana-lyses of the death rate of British and Frenchsoldiers sent to the tropics in the 19th cen-tury has suggested, for example, that it wasat least twice that of soldiers who stayedat home.

TOOLS OF EMPIRE

Some historians have argued that Europeanvulnerability to new diseases diminished fromthe mid-19th century as sanitary engineeringand new industrial technologies becameindispensable “tools of empire.” Accordingto this view, European imperialism was trans-formed by a technological revolution.Gunboats and increasingly sophisticatedweaponry, including single-shot breechloa-ders and machine guns, as well as innovations

4

in communication from steamships to rail-ways and submarine cables, gave Europeansoverwhelming superiority, enabling them toconsolidate and extend their empires inAfrica and Asia. Another key innovation inthis armory was the development of quinineas a prophylaxis against malaria, a diseaseendemic to tropical Africa – and the principalcause of European mortality – which hadbeen a deterrent to further penetration anddomination of the continent. The prophylac-tic use of quinine, which derives from a toxicalkaloid extracted from the bark of the cin-chona tree, a native of the Andes, allowedEuropeans to endure the deleterious effectsof tropical environments: medicine madethe exploitation of new territories viable inboth financial and human terms. Accordingto this narrative, later breakthroughs in germtheory, bacteriology, and parasitology fromthe 1870s and 1880s would be responsiblefor effecting a “health transition” which, inturn, propelled the “scramble” for empire.The development of tropical medicine as a

specialty and the identification of the causa-tive agents of many diseases between the1880s and the 1920s buttressed the cause ofempire. In 1883, the German bacteriologistRobert Koch identified the Vibrio choleraein Egypt and India; Alexandre Yersin andKitasato Shibasaburō isolated the bacillusresponsible for bubonic plague in Hong Kongin 1894; although Alphonse Laveran had dis-covered the protozoan responsible for malariain Algeria in 1880, it was Ronald Ross, work-ing for the Indian medical service, who iden-tified the female Anopheles mosquito as thedisease vector in 1897; and Aldo Castellaniestablished trypanosomes as the cause ofsleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis) – a para-sitic disease carried by the tsetse fly – inUganda in 1903. In 1900, following the1898 Spanish American War in Cuba, thecause of yellow fever (a virus transmitted bythe Aedes aegypti mosquito) was discovered

by the US Army Yellow Fever Commission,headed by Major Walter Reed.Until at least the mid-19th century, coloni-

zerswere primarily concernedwith safeguard-ing the health of the colonial community.While this enclavist approach persisted andled to policies of enforced segregation inmanycolonial contexts (notably SouthAfrica), therewas arguably a shift at the end of the centurytowards a more expansionist but nonethelessauthoritarian public health approach, witha focus on sanitary reform. The so-calledfounder of tropicalmedicine, Sir PatrickMan-son – who discovered that the mosquito wasthe host of the parasitic filarial worm thatcauses elephantiasis– founded theHongKongCollege of Medicine for Chinese in 1887 (sub-sequently helping to establish the LondonSchool of Tropical Medicine in 1899). In hisinaugural address as dean of the college, Man-son outlined a vision of empire in which theBritish crown colony was to serve as anenlightened hub for the global disseminationof scientific knowledge, which was destinedto transform East Asia.Although medicine and science could be

invoked by contemporaries in this way asinstruments of enlightenment and tools ofempire, there was a wide discrepancy betweentheory and practice, rhetoric and policy.Hong Kong, for example, despite the pivotalrole envisaged for it by Manson, did not havea purpose-built bacteriological laboratoryuntil 1906. Indeed, the notion of medicineand science as “tools of empire” has been cri-tiqued by many scholars on the ground that itflattens the complexity of empire, intimatingan imperial homogeneity and coherence thatdid not exist. It also assumes a diffusionistdynamic wherein resilient technologies pro-duced in the metropole are shipped out tothe imperial peripheries, with little reversetraffic.Evidence suggests that there was great var-

iation in the take-up and application of new

5

technologies across the diverse terrains ofempire. The transfer of technologies washighly mediated. Whereas white settler colo-nies within the British Empire, such asAustralia, strove to reproduce the infrastruc-tures of metropolitan institutions, in otherparts of the Empire, such as Africa, the med-ical presence was negligible and gearedpredominantly to a dispersed military per-sonnel. Medical practice and institutionalarrangements differed markedly from placeto place, just as they changed and wereadapted over time.Finally, other scholars have challenged the

exclusive emphasis on the modernizing stateand the overriding importance placed on“national” politics. They have pointed to therole of missionaries and other non-stateactors – individuals and collectives – whowere crucial to the formation of colonial med-icine and public health. And while highlight-ing the locally mediated nature of colonialmedical practice, they have accentuated thetrans-national and trans-colonial contextswhich shaped the development of biomedicalinstitutions.The efficacy of specific “tools of empire”

such as quinine has also been called into ques-tion. It has been argued that quinine may not,in fact, have been so widely consumed as it isoften claimed. In the case of French imperial-ism in Africa, for example, it has been shownthat quinine was not widely adopted as a pro-phylactic until well into the 20th century,while it may have been far less efficaciousthan is sometimes alleged. Furthermore,despite the emphasis on malaria as a threatto empire, colonial policy often had othermore pressing priorities. Colonial interven-tions designed to acclimatize unwholesomeforeign environments and reduce the healthrisks of colonization could often exacerbatethe situation they were intended to amelio-rate. One example is the ecological transfor-mation of western Bengal by the British in

the second half of the 19th century, whichwas calculated to expand the efficiency ofagricultural production with the constructionof dykes and irrigation canals but which, con-versely, served to spread malaria.In many settings, European moder-

nizing technologies created ecological crises,destroying indigenous social structures andenvironmental controls. In sub-SaharanAfrica, for example, tribal communities werereorganized, ecologies transformed by com-mercial agriculture, and the continent pro-gressively linked by rail, road, and shippingnetworks. African laborers migrated to thecities, swelling a new proletarian class in theurban slums. Such transformations helpedto produce epidemics of sleeping sicknesswhilst amplifying the threat from other dis-eases and acting as a driver of tuberculosis,a new disease imported from Europe. Colo-nial interventions in Africa were also to createanimal epidemics, such as the spread of rin-derpest, a viral infection which decimatedthe cattle population of South Africa in the1890s, with profound economic conse-quences for indigenous communities relianton cattle for their livelihood.There are many examples of such colo-

nial interventions that produced unforeseencounter-effects: from environmental andinfrastructural projects to public healthresponses. In French Indochina – part of afederation of French colonies and protecto-rates established in the 1860s – the construc-tion of railways to open up the country andallow for a more efficient distribution of qui-nine backfired as the railways helped tospread disease. The British response to theThird Plague Pandemic, which diffused glob-ally from China in the 1890s, killing some15 million people worldwide, was also coun-terproductive. The plague reached Bombay in1896, where it spread along the coast andinland. In order to avert the disease’s diffu-sion and minimize any impact on imperial

6

trade, colonial authorities implemented dra-conian sanitary measures, including enforcedhouse searches, quarantining, and a suspen-sion of pilgrimages. This colonial overreac-tion was to provoke resentment, lead torioting and, ultimately, serve as a catalystfor Indian radicalization.

MEDICINE AND THE COLONIAL STATE

To an extent, colonial medicine functioned asa means of integrating colonized peoples intothe institutions of the modern state. It servedto standardize behavior and practice, makingindigenous societies more tractable. Studies ofempire have stressed this political economy ofhealth and disease and, in particular, the roleof medical science as an ancillary of empire.A racial discourse of disease conflated biol-

ogy with politics: anxieties about the threat ofpathogenic microbes became inseparablefrom fears about the danger posed to whitebodies by the colonized. Diseases acquiredidentities, which linked them to specificlocales and the people who lived there. Thus,cholera was invariably racially profiled in19th-century Europe as an “Asiatic” diseaseand its original “home” tracked back to Ben-gal. The diffusion of disease was mapped as aone-way flow from South to North or East toWest, while medical knowhow circulated theother way: radiating outwards from the met-ropole. Indeed, this racial construction ofdisease as a menace from without arguablypersists in contemporary Western historiesof epidemic diseases (notably cholera andinfluenza) that focus wholly on the impactof infection in the West, while relegatingthe pandemic histories in Asia to a footnote.In the 19th and early 20th centuries, so-

called “filth-diseases,” such as the bubonic pla-gue, were linked to the insalubrious livingconditions and habits of native populations.Disease became an emblemof “backwardness”

and an obstruction to progress. Local culturalpractices and living spaces, associated withdirt and pollution, were pathologized, whilescience and medicine were racialized. Publichealth was used to warrant invasive publicworks as an imperative for security, while apaternalistic impulse to remold native socie-ties in the name of hygienic modernityobscured fundamental health inequalities.In examining this instrumentalization of

colonial medicine, historians have exploredthe entanglement of knowledge and power,and the “disciplinary” nature of colonial med-ical and hygienic practices. Such scholarshiphas also stressed colonial medicine’s disa-vowal of biosocial differences and its role inthe implementation of “governmentality” –the interpolative process by which subjectsare produced and governed.The use of quarantine measures in colonial

Australia during the 19th and early 20th cen-turies demonstrates how disease became pro-gressively entangled with social and politicalconcerns. Disease surveillance functioned asa means, not only of ensuring “health,” butof policing racial boundaries to ensure theintegrity of “white Australia.”Medicine’s dis-ciplinary capacity and the progressive incor-poration of medicine within the apparatusesof imperial administration were not solelythe preserve of European empire-buildingstates. In the Ottoman Empire, medicine wasa significant instrument of imperial power,particularly from the 19th century. In EastAsia, colonial medicine played an importantrole within Japanese imperial policy. Follow-ing the acquisition of Taiwan in 1895, theJapanese were intent on transforming theirfirst overseas possession into a “model col-ony.”They sought to do so bymobilizingmed-icine as part of a progressive, “civilizingmission” which would induce the island’snative population to embrace colonization.Similarly, US sanitation and disease-

control activities in Cuba in the late 1890s

7

were undertaken not simply as a means ofextending public health, but as a way of elim-inating opposition to the US expansionistambitions. One consequence of the US warwith Spain (1898), triggered by the Cubandebacle, was the colonization by the UnitedStates of the Philippines. There, medicinewas commandeered as part of an imperialeffort to suppress indigenous beliefs andsocial practices. Race and biology becameentangled, with medicine functioning as ameans of “civilizing” and subduing the popu-lation of a geographically dispersed archipel-ago. Public health assumed the modality of apacification campaign, while medical sciencewas integrated into the machinery of whatone historian has termed “the surveillancestate.” According to this interpretation,colonial operations of counterinsurgencymigrated back from the Philippines to theUnited States where they were instrumentalin the development of a federal security appa-ratus during World War I and beyond.

MIXED MEDICINES

There is, perhaps, a danger that the interrela-tionship between medicine and the colonialstate may be oversimplified: Western bio-medicine and indigenous healing practicesmay be viewed in binary terms with anemphasis on colonial hegemony and indige-nous resistance. Conceptualizing medicinein this way may lead historians to play downthe complex interactions between colonialauthorities and indigenous subjects.For one, conquest and colonialism exposed

Europeans to new medical knowledge. Whilethe notion of an induced immunity to small-pox using smallpox “scabs” had been knownin China from the 10th century CE, smallpoxinoculation, known as “variolation,” wasfamiliar in India and the Ottoman Empire,from whence it was successfully imported to

Britain in the 1700s. Second, “traditional”medical practices proved remarkably resilientand adaptive. Indigenous knowledge andWestern technology did not exist in starkopposition but rather interacted in a complexand evolving dynamic. Indeed, many histor-ians have suggested that the boundariesdemarcating one from the other were unsta-ble, arguing that colonial medical knowledgewas in part produced through encounterswith other cultures.Third, rather than being understood as a

homogenous institution, the colonial statemight best be viewed as an assemblage ofinstitutions and agents – both professionaland non-professional, formal and informal –with overlapping and often contradictorypriorities. In this context, many scholars havepointed to the incoherencies and contradic-tions within colonial biomedical discoursewhich posited social and cultural explana-tions of ‘nature,’ even as it endeavored to nat-uralize its authority. At the same time, insteadof viewing colonial medicine within a diffu-sionist framework (as an exportation fromthe metropole to the imperial periphery),recent research has indicated the varied andchanging forms of colonial interventionism,stressing the manner in which technologieswere negotiated, rejected, and absorbed indiverse settings – as well as acknowledgingthe influence of colonial medicine on metro-politan institutions and practices.Medical services were not uniformly

imposed upon colonized spaces; they were,in fact, highly mediated by local circum-stances and produced through negotiationand contestation. This is, perhaps, particu-larly evident in the European colonies ofSoutheast Asia. There, geopolitical, ethnic,and cultural complexities frustrated attemptsto superimpose categories and often led tocompromise and accommodation. Colonialmedicine in the French protectorate ofCambodia, for example, interacted with

8

indigenous cultural practices in an often frac-tious process that led to the creation of hybri-dizedmedicines. Similarly, in colonial Taiwan(1895–1945) medicine was not exclusivelyenlisted as a tool servicing Japanese nationalinterests and colonial rule. Instead, it wasmobilized for many competing purposesby an array of actors, both colonial and“native,” for often contradictory purposes.

SURVEILLANCE AND GLOBAL HEALTH

Empires thus helped to produce, extend,and entrench global networks. Ideas, com-modities, people, capital – and disease –circulated in ever greater numbers, withgreater speed. By the turn of the 19th and20th centuries, imperial flows were prompt-ing the development of new forms of regula-tory control. While it is certainly importantnot to overemphasize the novelty of theseimperial networks – and ignore patterns oftrans-continental interconnection that longpredated European empires – nonetheless,Western empires in the 19th century didtransform mobilities with the constructionof communication systems and the promo-tion of new technologies, including thesteamship, telegraphy, railways, and mass-circulation newspapers. Such networks alsoenabled the implementation of transnationaldisease surveillance mechanisms.Telegraphic communication was to trans-

form imperial governance, with implicationsfor the monitoring of disease. Whereas previ-ously information had traveled at the samespeed as infected bodies, from the mid-19thcentury communication and transport wereprogressively uncoupled. Messages sentthrough the telegraph could forestall diseaseby enabling, for example, the implementationof emergency prevention plans. One of theearliest such uses of the telegraph occurredduring the 1889–1892 “Russian” influenza,

which appears to have spread along trans-continental rail routes, circumnavigating theglobe in four months and leading to panicin Europe. If the telegraph could serve as apublic health tool, however, it could also cre-ate global volatility as news of distant epi-demics reverberated around the world,inducing panic on the global stock exchanges.The 19th century also saw the beginnings of

transnational and trans-imperial knowledgesharing. Cholera epidemics, which hadaffected Europe from the 1820s, led to a seriesof International Sanitary Conferences – thefirst of which took place in Paris in 1851.The meetings exposed deep-seated nationaland imperial differences, underlining the geo-political and economic issues at stake in theimplementation of quarantines. However, theyalso reflected a new impetus for cooperation.Delegates at the conferences sought to recon-cile imperial economic interests with securityfrom the threat of disease which threatenedto undermine those interests. In many waysthis tension between the need to preserve prof-itable flowswhile closing down other lethal cir-culations is one that resonates in an ever moreinterconnected post-imperial world.

LEGACIES OF EMPIRE

Although decolonization accelerated afterWorld War II, the colonial empire provideda model for transnational health organiza-tions in the aftermath of the conflict. Fromthe early 20th century, decolonization wasclosely connected to the establishment ofnew international institutions including theWorld Health Organization (WHO) in1948. The vision of global health in the 21stcentury – underpinned, as it is, by increas-ingly deterritorialized information networks –is discernibly different from that of thecolonial period. Nonetheless, there are con-spicuous continuities. Imperial forms of

9

hegemony may persist, sustained by – andperhaps even reinscribed within – newtechnologies. Corporate agendas may becomeentangled with the vested interests ofWesternstates. According to this “imperialist” view,profitable Western biotech initiatives in thedeveloping world serve to advance the inter-ests of the metropole, often at the expense ofthe host communities.Numerous health controversies at the

beginning of the 21st century have reprisedthe tensions and conflicts of the colonial past.Indonesia’s decision in 2007 to withhold sam-ples of avian influenza virus A (H5N1) fromthe WHO underscored the extent to whichthe legacies of empire continue to shape con-cerns in the present. While Indonesia – aDutch colony until 1945 – framed the West’sdemands as a denial of its sovereign rights

and title to its own biological resources, theWest viewed the issue of viral sample sharingwithin the context of global health securityand international law. Similarly, oppositionto the polio immunization campaign inPakistan and Afghanistan and the killing ofpublic health workers by the Taliban, reprisea history of indigenous resistance to colonialvaccination initiatives in the subcontinentduring the 19th century.Contemporary Western concerns about

“emerging diseases” also echo earlier anxietiesabout the danger posed to the metropole byimported “Asiatic” and “African” diseasesspreading through the multiplying circuitsof empire. In Emerging Infections: MicrobialThreats to Health in the United States, a scien-tific volume published by the US NationalAcademy of Sciences in 1992 that did much

Figure 1 Major H. Prudmore inoculating against plague, Mandalay, Burma, 1906.Source: Wellcome Library, London.

10

to promote the notion of disease emergence,the editors declare that “there is nowhere inthe world from which we are remote andno one from who we are disconnected.” Envi-ronmental change, new industrial processes,human behavior, political instability, andglobal interconnectedness are viewed as thecritical drivers of lethal new diseases whichemanate from the Earth’s dark places. Theworld depicted here is a world made andunmade by empire.Infectious diseases continue to be repre-

sented in popular culture through the prismof an imperial history and in relation to colo-nial cartographies of power. Pandemic thril-lers, such as Wolfgang Petersen’s Outbreak(1995), invariably locate the origins of novelinfectious diseases in a violent, post-colonialdeveloping world. Virulent pathogens, whichemerge to threaten the stability of the West,are construed as the inevitable by-productof conflict, insalubrious cultural practices,and a tropical environment that propagatesinfection.

SEE ALSO: Decline of empires; Drugs andempire; Environment and empire; Globalizationand empire; Humanitarianism and empire;Migrants and migration; Policing and colonialcontrol; Science, imperial; Slavery, institutionof; Technology and empire

FURTHER READING

Amrith, S. S. 2006. Decolonizing InternationalHealth: India and Southeast Asia, 1930–1965.Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Anderson,W. 2006. Colonial Pathologies: AmericanTropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Phil-ippines. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Arnold, D. 1993. Colonizing the Body: State Medi-cine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-CenturyIndia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Arnold, D. (Ed.) 1988. Imperial Medicine andIndigenous Societies. Manchester: ManchesterUniversity Press.

Arnold, D. (Ed.) 1996. Warm Climates and West-ern Medicine: Emergence of Tropical Medicine,1500–1900. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Au, S. 2011. Mixed Medicines: Health and Culturein French Colonial Cambodia. Chicago: Univer-sity of Chicago Press.

Bashford, A. 2004. Imperial Hygiene: A CriticalHistory of Colonialism, Nationalism and PublicHealth. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bashford, A. 2006.Medicine at the Border: Disease,Globalization and Security, 1850 to the Present.Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cook, S. F. andW.Borah. 1971. “TheAboriginal Pop-ulation ofHispaniola.” In S. F. Cook andW. Borah(Eds.),Essays inPopulationHistory:Mexicoand theCaribbean, Volume 1: 376–410. Berkeley: Univer-sity of California Press.

Crosby, A. 1972. The Columbian Exchange: Biolog-ical and Cultural Consequences of 1492. West-port, CT: Greenwood Press.

Cunningham, A. and B. Andrews (Eds.) 1997.Western Medicine as Contested Knowledge.Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Curson, P. H. 1985. Times of Crisis: Epidemics inSydney, 1788–1900. Sydney: Sydney Univer-sity Press.

Curtin, P. D. 1989. Death by Migration: Europe’sEncounter with the Tropical World in the Nine-teenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge Univer-sity Press.

Diamond, J. 2005. Guns, Germs and Steel: A ShortHistory of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years.London: Vintage. First published 1997 byChatto & Windus.

Dols, M. W. 1977. The Black Death in the MiddleEast. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Echenberg, M. 2010. Plague Ports: The GlobalUrban Impact of Bubonic Plague, 1894–1901.New York: New York University Press.

Ernst, W. 2007. “Beyond East and West: From theHistory of Colonial Medicine to a Social Historyof Medicine(s) in South Asia.” Social History ofMedicine, 20(3): 505–524.

Espinosa,M. 2009. Epidemic Invasions: Yellow FeverandtheLimitsofCubanIndependence,1878–1930.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hamlin, C. 2009. Cholera: The Biography. Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Harrison, M. 1994. Public Health in British India:Anglo-Indian Preventive Medicine, 1859–1914.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

11

Harrison, M. 2012. Contagion: How CommerceHas Spread Disease. New Haven: Yale Univer-sity Press.

Headrick,D.R.1981.TheToolsofEmpire:Technologyand European Imperialism in the NineteenthCentury. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jasanoff, S. 2006. “Biotechnology and Empire: TheGlobal Power of Seeds and Science.” Osiris,21(1): 273–292.

Jones, D. S. 2003. “Virgin Soils Revisited.”Williamand Mary Quarterly, 60(4): 703–742.

King, N. B. 2002. “Security, Disease, Commerce:Ideologies of Postcolonial Global Health.” SocialStudies of Science, 32(5–6): 763–789.

Le Roy Ladurie, E. 1973. “Un concept: l’unificationmicrobienne du monde XIVe–XVIIe-siècles.”Revue suisse d’histoire, 23(4): 627–696; trans.S. Reynolds and B. Reynolds as “A Concept:The Unification of the Globe by Disease”(1981), in The Mind and Method of the Histo-rian: 28–83. Brighton: Harvester Press.

Little, L. K. 2007. “Life and Afterlife of the First Pla-gue Pandemic.” In L. K. Little (Ed.), Plague andthe End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750:8–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Liu, M. S. 2009. Prescribing Colonization: The Roleof Medical Practices and Policies in Japan-RuledTaiwan, 1895–1945. Ann Arbor, MI: Associa-tion for Asian Studies.

Lyons, M. 1992. The Colonial Disease: A SocialHistory of Sleeping Sickness in Northern Zaire,

1900–1940. Cambridge: Cambridge Univer-sity Press.

McCoy, A. W. 2009. Policing America’s Empire:The United States, the Philippines, and the Riseof the Surveillance State. Madison: Universityof Wisconsin Press.

MacLeod, R. M. (Ed.) 1988. Disease, Medicine, andEmpire: Perspectives on Western Medicine andthe Experience of European Expansion. London:Routledge.

McNeill, J. R. 2010. Mosquito Empires: Ecologyand War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620–1914.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McNeill, W. H. 1979. Plagues and Peoples. London:Penguin. First published 1976 by Anchor Press.

Morgan, K. 2007. Slavery and the British Empire:From Africa to America. Oxford: Oxford Uni-versity Press.

Packard, R. M. 2007. The Making of a Tropical Dis-ease: A Short History of Malaria. Baltimore:Johns Hopkins University Press.

Panzac, D. 1985. La peste dans l’empire Ottoman1700–1850. Louvain: Pesters.

Quétel, C. 1990. The History of Syphilis, trans.J. Braddock and B. Pike. Cambridge: Polity.

Rosenberg, C. E. 1992. Explaining Epidemicsand Other Studies in the History of Medicine.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vaughan, M. 1991. Curing Their Ills: ColonialPower and African Illness. Stanford: StanfordUniversity Press.

12

Related Documents