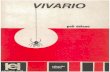

Delano and the United Farm Workers Movement : A Grassroots History A Senior Honors Project Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History; University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For Bachelor of History with Honors By John Anthony Gonzales May 15, 2014 Committee: Prof. Richard Rath, Mentor Dr. Loriena Yoncura Prof. Herbert F. Ziegler

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Delano and the United Farm Workers Movement: A Grassroots History

A Senior Honors Project Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History; University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For Bachelor of History with Honors

By John Anthony Gonzales May 15, 2014

Committee: Prof. Richard Rath, Mentor

Dr. Loriena Yoncura Prof. Herbert F. Ziegler

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements i Abstract ii List of Figures iii Chapter One: Preface 1 Chapter Two: Northbound 4 Chapter Three: The Juan Crow Experience 8 Chapter Four: The Bracero Years 15 Chapter Five: Literature Review 20 Chapter Six: A House Divided 24 Chapter Seven: The King is Dead… 28 Conclusion 33 Family Tree 34 Appendix A: Consent Form 35 Bibliography 36

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank everyone involved in this research project; interviewees, my

mentor Richard Rath, and committee members as well. I would also like to thank

Professor Brown for offering a very instructive and informative history 360 course,

which opened up many doors to primary resource use and acquirement. And, I cannot

forget thank Joe Mendez for all of his assistance and instruction on putting together a

PowerPoint and poster presentation, because they were my first attempts at both and I

was in much need of guidance. Mostly I would like to thank my family whose life

experiences and history made this project possible.

Muchas gracias.

i

Abstract

The proposed research project will be an historical interpretation of, and

investigation into, the social and political norms of the mid-twentieth century United

States that spurred the unification of a segmented community into a political body of

mass influence. Although the research will cover the general history of Cesar Chavez and

the United Farm Workers Movement, the study will focus on the pivotal points that

altered the course of personal, political and group histories and identities, and the legacies

these events left behind. For this particular project data will be collected from conducting

interviews with family members who resided in the area and/or participated in the events

during the described era, sorting through government documents and archived periodicals

mainly from the state of California as well as several publications from the Pacific

Northwest and the Four Corners region of the United States. In addition, an abundance of

published articles and secondary resources will be examined for background information.

The goal of the study is two fold, to provide a concise examination of the development of

the United Farm Workers Union and Cesar Chavez in parallel with the history of Delano,

California. The second aim of the project is to expand on prior research both in favor and

in opposition of the UFW in relation to journey and experiences of my own family as to

offer the reader or audience an insider prospective of events that changed American

history in the Southwest.

Keywords: Migrant Farm Worker Delano

ii

Figures and Charts

1. Family Tree; Illustration of relationship between the Gonzales/Hernandez and Chavez

families

iii

Preface

Pausing at an intersection on another beautiful day in Hawai’i nei,1 the type of

day where the sky’s ocean blue canvas calls out and says, “come, swim in my reflective

elegance and surf like a soaring egret on waves of air.” The few and far between cotton

candy pillows of condensed water vapor up above were hovering amongst, and

intertwined within, the Ko’olau’s2 providing moisture and sustenance to the foliage and

fauna down below. Situated on the mauka3 side of the intersection was an encouraging

sight of a group of collective bargainers sharing a human experience and an American

tradition while demonstrating their solidarity in opposition to recent unfair labor practices

on behalf of a well-known United States conglomerate.4

The demonstrators were boycotting the importation, and use of, nonunion workers and

the company’s refusal to provide proper wages adequate for health and pension

contributions. Apparently, this is a nationwide bone of contention between unions and the

conglomerate, which is reminiscent of the early days of the history of collective

bargaining.5 Yet, as I gazed upon the boycotters with a mix of admiration and sympathy,

1 1 http://www.oocities.org/olelo.geo/workshop.htm Hawai’i nei; beloved Hawai’i, E hau`oli e nâ `ôpio o Hawai’i nei [eh hau oh' lee- (y)eh NAH OH pee-(Y)OH' hah vah ee nei] Happy the youth of beloved Hawai’i 2 http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/321985/Koolau-Range; Ko’olau Range, mountains paralleling for 37 miles (60 km) the eastern coast of Oahu island, Hawaii 3 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mauka; Mauka: toward the mountains: inland, upland 4 Walgreens Drug Stores Inc. 5 Perreira, Randy. “Hawai’i State AFL-CIO President, Letter: Workers Still Stand Against Walgreens.” The Hawai’i Independent, April 2010. http://hawaiiindependent.net/story/letter-workers-unions-still-standing-against-walgreens; Vena, Joseph R. “Local carpenter Union Takes Issue With Construction of Bayonne Walgreen’s.” NJ.com: True jersey, November 26, 2013. http://www.nj.com/hudson/index.ssf/2013/11/local_carpenters_union_has_bone_to_pick_with_in-progress_bayonne_walgreens.html; Raferty, Miriam. “Shame On Walgreen’s: Labor Dispute Takes to the Streets.” East County Magazine, September 2010. http://www.eastcountymagazine.org/node/4293.

I couldn’t help but feeling unsatisfied and a little empty-hearted as something was amiss.

Where was the red and black?6 In light of the issues being confronted there should have

been a black eagle with wings a blazing as a symbol of unity and strength flying overhead

accompanied by the letters UFW printed across a red banner. What’s more, what would

Cesar Chavez and the many other individuals who stood up and confronted injustice

when it was demanded of them think of the situation? Is the union aware, or yet, still

involved with such issues?

During this interval of daydreaming as this perplexing image ricocheted like a

pinball in an arcade game off of my cerebellum, cerebrum, and so forth, I began to

ponder the history and development of the United Farm Workers Union, as well as its

leaders, and the bygone days of my family and their time spent in Delano and the

California grapevine in the midst of a civil rights movement. Growing up in Los Angeles

as a person of Mexican ancestry and as a descendant of migrant farm workers of Delano

and union participants, my siblings and I were frequently reminded of our family’s

relationship with La Causa and the Chavez family. Not a funeral, birthday party, or

family reunion passed without the mention of Cesar Chavez and the Union, or a retelling

of a personal experience from the fields.

However, it was then that I came to the realization that these stories, whether their

accounts be concise or exaggerated, represent a remarkable portion of United States

history, and that it was time to take a closer and personal look at these events and the

2

6 Taylor, Ronald B. Chavez and the Farm Workers. (Mass. USA: Beacon Press, 1975) 115-116. Red and Black are the colors of the United Farm Workers Union flag designed by Manuel Chavez, Cesar’s cousin, a red banner with a black eagle in the center of a White circle. (Insert more about flag from Lavy)

social issues surrounding them for the purposes of updating and reinvigorating this area

of study with the possibility of it being brought to the forefront of the United States

education system in the same manner as African-American studies, and also for the

preservation of my families involvement in this historic period.

3

Northbound

The early part of the twentieth century is a turbulent chapter in the history of

Western Nations. The United States was basking in the glory of their victory over a

weakened Spain in the Spanish-American War of 1898, a victory that endorsed the Euro-

American doctrine of “The White Man’s Burden,”7 and permitted them to offer the

former Spanish territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, Philippines, and Cuba the freedom to be

colonized yet again.8 In addition, President McKinley, through his adamant, dated belief

in “Manifest Destiny,”9 annexed the sovereign nation of Hawai’i thus relieving the select

few Anglo-American businessmen who had staged an illegal coup d’état several years

prior in 1893 of the weight of dealing with the legal repercussions pertaining to their

corrupt behavior. In effect creating an Island empire that stretched from the Atlantic to

the Pacific.10

Meanwhile, the old world European Empires were being threatened by escalating

thoughts of nationhood and self-determination that foretold the looming of the Great

4

7 Murphy, Gretchen. Shadowing the White Man’s Burden: U.S. Imperialism and the Problem of the Color Line. (New York, NY, USA: New York University Press (NYU Press), 2010) 1-2. The White Man’s Burden is a concept that White people of developed nations have a duty to enlighten Non-Whites of the globe to the ideals of their “superior” culture and civilization. An opinion taken up by the majority of Anglo-Americans of the period, including the renowned poet and author Rudyard Kipling who advocated for the philosophy in his 1899 poem The White man’s Burden. (Originally dubbed The United States and the Philippines) 8 Botero, Rodrigo. Ambivalent Embrace: America’s Relations with Spain from the Revolutionary War to the Cold War. (Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Press, 2000) 91-95; Perez, Louis A. War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography. (Chapel Hill, NC, USA: University of North Carolina Press, 1998) 1, 131. 9 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/manifest destiny. In the mid-19th century expansion to the Pacific was regarded as the Manifest Destiny of the United States>; broadly: viewed as an ostensibly benevolent or necessary geopolitical policy of imperialistic expansion. The phrase was coined by John L. Sullivan in 1845 and is similar in ideology to the “White Man’s Burden” due to its assumption that United States culture is superior. 10 Silva, Noenoe K. Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism. (Durham, NC, USA: Duke University Press, 1996) 123-163; Botero, 2000, 91; Perez, 1998, 111.

War.11 Likewise, the largest nation in Central America, Mexico, was about to be thrown

into another tumultuous revolution approximately one hundred years after its fight for

independence from Spain.12

It was in this setting that the Gonzales and Hernandez families participated in one

of several massive human migrations in the history of North America as they journeyed

the perilous path from war torn, Revolutionary Mexico into what is now the

Southwestern United States. Claro Gonzales and Santiago Arezmendi Hernandez, the

individual patriarchs of each family, led their clans across the United States border and

into the North American Southwest leaving behind their respective homeland, a nation in

the throes of a revolution that divided families and pitted friend against friend. Traveling

in the company of an entire generation of migrants, who were never given the option or

same consideration of political asylum as other war refugees, these two sets of kin would

traverse through Arizona and later follow the blossoming orchards into the San Joaquin

Valley and transplant their roots in Delano, California where their life destinies would

intertwine with another Mexican migrant family who had traveled the same path decades

before, the Librado Chavez Clan. It is in the small railroad town of Delano where these

three families would become one through the experience of marriage, camaraderie and

life struggles. And, in doing so these families unwittingly wove themselves into the itchy,

burlap fabric of United States History.

The second decade of the nineteen hundreds was a coarse and chaotic one for

Mexico and its various citizens. The Grito,13 the call to war for the revolution of 1810

5

11 Tucker, Spencer C. Great War, 1914-1918. (London, GBR: UCL Press, 1998) xix, 172, 198, 217. 12 kirkwood, Burton. History of Mexico. (Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Press, 2000) 131-136. 13 The Grito de Dolores is an iconic piece of Mexican History derived from the 1810 Revolution when it was used as a call for justice and war. (Burton, 2000, 81)

that would again be used one hundred years later in 1910 resulted in the creation of

various armed political and military parties that divided up communities and loyalties

alike. The world of the old aristocratic guard was being turned upside down and

traditions were being destroyed as revolutionary leaders in the north and south demanded

and fought for agrarian reform, a fair democratic vote, and the end to the Hacienda

system. These issues were disputed on battlefields throughout Mexico, and many of these

battles took place in the central states of Guanajuato, the birthplace of the Grito,

Michoacán and Jalisco.14

Midway through the decade a young Claro Gonzales chose to leave the turbulence

of his home country behind and pursue a life less extraordinary for his prospective

family. Thus the future patriarch of the Gonzales clan said his farewells to the land of his

birth, Mexticacan, Jalisco, and ventured forth into the world of the semi-known, El

Norte/the North. In the year 1915 the ordeal of crossing the border entailed a long train

ride, or horse and carriage, to Northern Mexico and the cost of twenty-five cents for the

purchase of a passport. Once Claro entered the United States he declared his loyalty as a

hopeful citizen by doing something unexpected of someone who could be considered a

refugee of war, but not uncommon for a Mexican migrant. He registered for the armed

forces, and at a time when the Western World was on the verge of war itself. Around the

same time another young man by the name of Santiago Hernandez departed from the

historic state of Zacatecas in the midst of the Revolution and headed to the land of

6

14 Benjamin, Thomas, Revolucion: Mexico’s Great Revolution as Memory, Myth, and History (Texas, USA, University of Texas Press, 2000) 20-21, 53; Kirkwood, Burton, History of Mexico (CT. USA, Greenwood Press) CH. 8.

opportunity in the north for many of the same reasons as Claro Gonzales including the

prosperity of his prospective families.15

Claro’s course of exploration for an improved and secure livelihood placed him in

Blythe, California, a small agricultural town situated along the Colorado River and

abutting the Arizona/California border in the northern part of the Sonoran Desert where

he settled down and became acquainted with a demure Indigenous-Mexican woman who

would eventually become his wife. Francesca Guzman, originally from Guanajuato, and

Claro would go on to produce a dynasty of eleven children, four boys; Claro Jr. “Lito,”

Julio, Lucio “Chio,” Jose Roberto “Tete,” and seven girls; Maryanne, Zenaida, Margarita,

Thelaria, Simona, Esperanza, and Esther “Tita.” 16

This first generation of American born Gonzales’ would be the ones to make the official

transition from Mexican migrant to Mexican-American through their sweat, tears, joy and

laughter, and the smile now cry later dogma of the emerging Xicano.17

7

15 Gonzales Sr., Julio. Unpublished interview with Grandfather #1. Phone interview, December 16, 2013. 16 Gonzales Sr., Julio, 2013. (Insert more details about bisabuelo santi’s journey) 17 Montejano, David. Quixote's Soldiers: A Local History of the Chicano Movement 1966-1981 (Austin, Texas, USA: University of Texas Press, 2010) 2-3, 9-11. Chicano/Xicano is a term that emerged in the 1960’s as part of an effort by U.S. citizens of Mexican ancestry to establish a cultural identity for the purpose of a social empowerment. Moraga, Cherrie. Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness: Writings, 2000-2010. (Durham, NC, USA: Duke University Press, 2011), xxiii. "... spell Xicana and Xicano (Chicana and Chicano) with an X (the Nahuatl spelling of the “ch” sound) to indicate a reemerging política, especially among young people, grounded in Indigenous American belief systems and identities."

The Juan Crow Experience

The post war years of the mid 1940’s brought on another age of negative political

and social interest for the Mexican migrant community in the Southwest. Around this

time mainstream Americans were still reeling from the Zoot Suit riots of 1943, 18 and

returning soldiers along with numerous “Okie”19 migrants who had arrived in the

Southwest a decade earlier as refugees of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression were

given preference in the job market. Meanwhile the marginalized Mexican community

anguished under the boot of the Juan Crow social policies, the counterpart to the Jim

Crow segregation laws of the post-Reconstruction South.20 Identical to the post-Civil War

South, ethnic groups and segregation in the American Southwest were peas in a pod, a

circumstance that distorted the concept of United States citizenship and who had the right

to it. Juan Crow adorned in his Sombrero, cotton khakis and leather sandals, along with

his stereotypes and misconceptions reinforced this national ideal.21

8

18 Kathy, Peiss. Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style. (Philadelphia, PA, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011) 2. “Zoot,’’ says Cab Calloway’s Hepster’s Dictionary, means something done or worn in an exaggerated style: the long killer-diller coat with a drape shape and wide shoulders; pants with reet-pleats, billowing out at the knees, tightly tapered and pegged at the ankles; a porkpie or wide-brimmed hat; pointed or thick-soled shoes; and a long, dangling keychain… The Zoot-Suit was associated with racial and ethnic minorities and working-class youth;” Mazon, Mauricio. The Zoot-Suit Riots: The Psychology Of Symbolic Annihilation. (Austin, TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 1984) 1; Taylor, 1975, 79-80. The Zoot-Suit Riots were a set of incidents that occurred in California in the summer of 1943 with the most notable of the events taking place in Los Angeles between June 3 and 13. During this period United States military personnel and Anglo citizens brutally attacked, stripped, and raped individuals donning Zoot Suits, mainly those of Mexican descent, although Filipinos and African-Americans were often caught in the crossfire as well. 19 Babb, Sanora, Dorothy Babb, and Douglas Wixson. On the Dirty Plate Trail: The Dust Bowl Refugee Camps. (Austin, TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 2007) 5; Taylor, 1975, 47. 20 Lewis, Catherine, M., and Richard J. Lewis. Jim Crow America: A Documentary History (Fayetteville, AR, USA: University of Arkansas Press, 2009) xiii. 21 Rivera, John-Micheal. Emergence of Mexican America: Recovering Stories of Mexican Peoplehood in U.S. Culture. (New York, NY, USA: New York University Press, 2006) 152.

These unconstitutional policies were designed to restrict Mexicans, and in most

areas of the Southwest African-Americans and Filipinos as well, from certain business

and residential districts and maintained separation of the races in theatres, restaurants,

public parks, schools and municipal buildings, etc. And, as in the Southern United States

the conditions of the facilities and structures set aside for non-whites were unkempt and

substandard.22 Not even in death was there a reprieve from this social policy since burials

and funerals were segregated as well.

This social separation, which some argue was a de facto practice and not de jure

as in the Southern United States,23 was, nevertheless enforced by the local police and the

courts and reinforced with placards and billboards illustrating the expected social

conduct. Signs that read “No Dogs, No Negroes, No Mexicans or Spanish Allowed”

reigned all through the Southwest along highways and byways, and in the windows of

commercial buildings lining the Mainstreets of Any-town USA, including establishments

advertised as “Mexican Restaurants.” Oftentimes these signs simply stated, “We Serve

Whites Only.”24

Although the environment was not quite yet the pressure cooker on the verge of

explosion as it was in the Deep South, tensions in the Southwest mounted more akin to a

crock pot; slow and low and set it and forget it until the dish is ready to serve. Be that as

it may, this does not necessarily denote that the Mexican population accepted their

9

22 Donato, Ruben, and Jarrod S. Hanson. “Legally White, Socially ‘Mexican’ The Politics of De Jure and De Facto School Segregation in the American Southwest.” Harvard Educational Review 82, no. No. 2 (Summer 2012): 205. 23 Donato, and Hanson, 2012. 24 Orozco, Cynthia E. No Mexicans, or Dogs Allowed: The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. (Austin TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 2009) 17, 30; Levy, 1975, 175. In some cases these signs stated “Whites and Japanese only,” and often there were cleaner, segregated areas of business establishments set aside for Whites and Japanese while people of color were relegated to the opposite unkempt areas.

societal fate with complacency. Young and old alike went about their day-to-day

existence while simultaneously behaving in a manner of obedience with non-compliance

irritating the powers that be like a stone in a boot that refuses to be removed, including

the Gonzales brothers.

On a day like any other in the American Southwest when the sun is vibrant in the

sky and the cool, dry atmosphere chap’s a persons face, Julio, “Chio,” and a childhood

friend acted out of exasperation in a display of youthful innocence as the three boys took

an opportunity to rebel in a way only children can. The air was still and the day was hot

whilst the boys engaged in their usual hustle of shining shoes in the streets of Blythe for

locals and military alike. Stationed in front of an eatery that paraded a placard

announcing the social restrictions of the period, the pensive juveniles sat and observed as

the Anglo clientele entered the said eatery at their leisure, and departed with gratified

grins. Every party occupied themselves with idle chitchat in a facade of self-importance

as they sashayed their way past the boys and pretended they did not exist. At that point,

melancholy turned to anger because “we were tired of seeing those signs,” and just as an

Anglo-American serviceman was about to access his way into a cool climate of comfort

and nourishment that has been forbidden to the descendants of Anahuac,25 the youngsters

hollered towards the soldier, “Hey, you can’t go in there.” The serviceman looked at the

boys and questioned “why?” with a smirk in his eye. “Look-it,” the boys said, “there’s a

10

25 Rostas, Susanna. Mesoamerican Worlds: Carrying the World: The Concheros Dance in Mexico City. (Boulder, CO, USA: University Press of Colorado, 2009) 179, 267.The term refers to the name of the origin of the founders of Tenochtitlan and it is also a term referring to the known world in Mexico before the arrival of the Europeans; Bierhorst, John. Ballads of the Lords of New Spain: The Codex Romances de Los Señores de La Nueva España. (Austin, TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 2009) 171-172, 190. Anahuac = besides to the water (Tenochtitlan); Nadaillac, Marquis De , and John Muller. Prehistoric America. (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA: University of Alabama Press, 2005) 271. The land of the Nahuas near the water.

sign there, no Mexicans, or blacks, or dogs allowed. You’re a dog.” Boom! The

serviceman gave chase, but the boys were too sly and too quick and their knowledge of

the streets helped them disappear like a magicians trick. “We took off, and we knew all

the alleys and hideouts so he couldn’t catch us. We were little.”26

However, not all encounters with Juan Crow were as jovial and lighthearted as the

Incident described above. Moreover, in the course of its existence no person of Mexican

ancestry was shielded from the fluttering wings of Juan Crow.

Not even those who passed for Anglo’s due to their light complexions, because our

surnames are worn like a scarlet letter and yellow star27 that broadcasts our true identity

that cannot be concealed.

Humiliation and degradation were a constant fact of life in all arenas of

Southwestern society, and not long after the previous rebellious incident the inseparable

brothers experienced another demeaning encounter with the vast wingspan of Mister

crow. The episode took place while the two were in transit to Delano from Blythe on the

famed greyhound bus-line. The bus was filled to capacity and Julio and “Chio” rode in

comfort until the former was ordered to give up his seat to another patron, an Anglo

woman.

In the course of the route an intoxicated male, who happened to be an African-

American, seated himself next to the aforementioned female, a social taboo in that period

11

26 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview #2 with Tio Chio at Tampico Taqueria. Face to face, February 23, 2014. 27 Ozsvath, Zsuzsanna, and David Patterson. When the Danube Ran Red. (Syracuse, NY, USA: Syracuse University Press, 2010) 72. “the law demanding that Jews wear a 3.8 x 3.8– inch, six-pointed, canary-yellow Star of David, made of cloth and sewn on the left chest of the clothing of every Jewish man, woman, and child under the sun.”

stemming from the propaganda and fears of early Anglo-American society that stressed

the sanctity of white women and their need for protection from “black beasts,” and their

“sexual transgressions.”28 So, at the following terminus in the town of Gorman,

California the bus driver, in a presumed act of chivalry, took action to right the wrong

and stated, “I guess we’re going to have to make some changes here,” and ordered Julio

to remove himself from his more comfortable seat in the back of the bus and give it up

for the Anglo women. A rare sight in those days, since the back of the bus was usually

reserved and separated for people of color. But, “they made him do that.”29

Cesar Chavez similarly experienced his fair share of humiliation as a youth, and

during his years serving as an enlisted serviceman in the United States Navy. It was

around this time that another incident occurred that was common among the Mexican

community who had to live under the grasp of Juan Crow in the Southwest. On a fateful

evening while visiting home on a weekend leave, Cesar along with a few sailor friends

decided to attend a picture show at the local theatre in Delano. Except this time around

young Chavez felt a surge of frustration overtake his reasoning, a frustration that had

been lingering in the crevices of his mind since his youth when he was shunned and

turned away from an eatery known for its delicious hamburgers and its White Trade Only

business policy, therefore he resolved that he could no longer bear the burden of shame

thrust upon him by the majority of White America.30 So, in Rosa Parks fashion, instead of

12

28 Leiter, Andrew B. Southern Literary Studies: In the Shadow of the Black Beast: African American Masculinity in the Harlem and Southern Renaissance. (Baton Rouge, LA, USA: Louisiana State University Press (LSU Press), 2010) 3, 15, 94, 135. 29 Gonzales Sr., Julio. Unpublished interview with Grandfather #2. Phone interview, April 14, 2014; Gonzales, Lucio, 2014. 30 Levy, 1975, 84-85; London, Anderson, 1970, 143; Taylor, 1975, 62; Taylor offers a different telling of the theatre story. In his book, Chavez and the farm Workers, the incident occurs in 1943 while Chavez does not join the Navy until 1944.

being relegated to the darker side of the theatre on the right he dared to occupy a seat on

the left and more comfortable section of the theatre reserved for whites and Japanese,

allowed sign where he would come to find out that he was terribly mistaken. Even though

he was dressed in full military regalia the Anglo patrons within the diner reacted instantly

to his physical appearance rather than his uniform, where upon they proceeded to

bombard him with kicks and punches and held a knife to his throat. After which they

removed him from the premises. “They kicked him out, and he was in uniform.” The

incident left a permanent scar where the said knife had cut into his skin, and on his self-

respect.31

Juan Crow policies also outlawed and forbade the practice of speaking Spanish

anywhere in American territory,32 and it was the norm for individuals of Mexican descent

to be persecuted for speaking the colonial language of their motherland, despite that it

was a right that was guaranteed to Mexican citizens of the newly claimed territory under

the Hidalgo Treaty.33 Authorities in all settings of the Southwest were sure to make an

example of anyone publicly speaking Spanish, children or adults. For instance, in Los

Angeles police were known for their brutality against Spanish speakers, and Mexicans in

general, that often exceeded the harsh treatment of African-Americans.34

It was no different for the younger generation, as they had to contend with their

own realities of Juan Crow. Especially in the public school system where Spanish-

13 31 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio,” 2014. After relating this incident with me my Tio explained that these were some of the issues theat led to development of the G.I. Bill. Otherwise knoen as the Servicemen’s readjustment Act of 1944. 32 Roca, Ana, and John M. Lipski, eds. Studies in Anthropological Linguistics: Spanish in the United States: Linguistic Contact and Diversity. Vol. #6. (Stuttgart, DEU : Walter de Gruyter, 2011) 122. 33 Burrill, Donald R. Servants of the Law: Judicial Politics on the California Frontier, 1849-1889. (Blue Ridge Summit, PA, USA: University press of America, 2010) 53-56. 34 London, Joan, and Henry Anderson. So Shall Ye Reap. (New York, USA: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1970) 144;Taylor, Ronald B. Chavez and the Farm Workers. (Mass. USA: Beacon Press, 1975) 64, 162.

speaking children were separated into dilapidated classrooms and taught little or close to

nothing in regards to school instruction. It has been noted that these institutions “provided

little more than childcare service.”35 Furthermore, various forms of discipline were used

on Mexican schoolchildren to discourage the use of Spanish in public schools such as

running laps, wearing signs that declared you a mischief maker, and scrawling hundreds

of oath’s on the blackboard to never again use your first language. And, in Texas the

physical punishment of the children of Mexican migrant families for using Spanish was a

common occurrence. Survival looked grim in this setting where substandard education

and segregation in a school system that outlawed the Spanish language under threat of

physical punishment was a normal social custom, which is the reason why most Mexican

students chose to drop out of this system by the ninth grade, and sometimes as early as

the sixth grade36, due to its lack of sincerity and opportunities in favor of hard labor in the

fields and/or the street life.37

These immoral policies justified by the misconceptions and xenophobic fears of

Anglo-Americans and would continue on into the mid-twentieth century until the

nationwide eruption of demands for equality and self-respect among a variety of groups

would shake, rattle and roll the status quo, the Civil Rights Movement.

14

35 Kushner, Sam. Long Road To Delano. First Edition. (New York, USA: International Publishers Co., Inc., 1975) 26; London and Anderson, 1970, 142. 36 Gonzales Sr., Julio, 2014. “Lito began working at the age of 13 and left school in the sixth grade. He was a sharp dresser and had nicer clothes than the teachers, because he was making a lot of money back then. He used to show up to school in a sports coat and all that” 37 Levy, Jacques E. Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. 1st ed. (New York: Norton Publishing, 1975) 65; Taylor, 1975, 64, 162; London and Anderson, 1970, 144.

The Bracero38 Years

In addition to the social tensions that arose from Juan Crow policies and the

plethora of veterans returning to the workforce at the end of WWII, the continuous

extension of the Bracero Act39 was an enormous source of strife that was imposed on the

Mexican farm workers daily struggle to survive. Political in form and social in nature,

and to some degree still lingering in today’s state policies, this policy is rooted in the

eternal and controversial debate over immigration in a society of immigrants that was

sparked by the 1492 offshore anchoring of Columbus. A game of chess where copper-

toned bodies are used as insulation between the government nobility and the taxpaying

citizenry hungry for the sustainable employment that their nation has uniformly

outsourced in the name of economic growth.

Constantly in the midst of this argument based on stereotypes and misinformation

has been the Mexican community; whether they are United States citizens or Mexican

nationals this group is continuously utilized by the administrative powers to detract

attention from the real issues behind the economic instability and unemployment among

Americans. All the while the blame is placed on the hard working, low paid migrant

worker, and in some cases government policies are drawn up to create tension and

division within a presumed unified ethnic group.

15

38 Kushner, 1975, (?). Braceros—the Spanish equivalent of a farm hand, one who works with his arms (brazos). 39 Bender, Steven. Greasers and Gringos: Latinos, Law, and the American Imagination (New York: New York University Press, 2003) 135.

For as long as American farm workers have been attempting to organize in resistance to

their unfair treatment the government has been assisting the Agricultural sector in

maintaining their business as usual system of providing the nation with fresh

produce through underhanded, back-door bargaining’s that are later implemented into

law. The fact that the Agricultural sector was declared exempt from the nineteen thirty-

five Wagner Act giving employees the right to engage in collective bargaining, and when

one observes the immigration policies of the United States in the early and mid-twentieth

century this blatant practice of one hand washes the other is made quite apparent.40

The Bracero41 Act and its predecessors are but a few examples of these

clandestinely negotiated and economically biased policies. The true beginnings of the

Bracero Program, informally lasting from nineteen seventeen to nineteen sixty-four, lie

in the World War One immigration quota strategies introduced to help supplement an

agricultural workforce that was eventually going to be shipped off to one of modern

histories bloodiest wars.42 In nineteen forty-two another immigration work importation

strategy was enacted to, once again, supplement the lack of agricultural workers due to

the wartime draft of American workers, Mexican-Americans included. This policy was

also intended to replace the Japanese workforce that had recently been imprisoned in

internment camps in the west and most importantly the restless Okie community that left

the fields for the wartime production line and was sympathetic to union organization and

considered a bad influence on the other migrant communities.43 Theoretically, the

16

40 London and Anderso, 1970, 5. 41 Bracero/Arm-man, strong-arm, arm (London and Anderson, 1970, p. 10; Taylor, 1970, p. 67) 42 Garcia, Ruben and Grown, Caren, Marginal Workers: How Legal Default Lines Divide Workers and Leave Them without Protection. (New York University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2012) 87. 43 Bender, 2003, 135; Taylor, 1970, 67.

bracero would exist alongside Rosy the Riveter as the nations life saving workforce of

World War Two.44

The certified policy that would officially be referred to as the Bracero Act was

enacted in nineteen forty-eight and its benefits and backlashes were immediately felt

throughout the farming community. Aside from the economic benefits that could be

considered miniscule when contrasted with the degradation and disenfranchisement that

the Mexican national was subjected to, the lucrative benefits that were reaped from this

program were solely in the hands of the growers and ranchers owing to the Bracero Act’s

uniqueness and design which put the financial responsibilities of healthcare and housing,

transportation and administration of the entire program on the federal government, giving

growers a free ride to profitville.45 This in combination with the powerful influence of

ranchers in the law enforcement and political realms of the San Joaquin valley was a

surefire recipe for a totalitarian work and social environment. A setting that the Mexican

farm worker, whether citizen or national, just like the migrant Okie of the Dustbowl era

had to live with in order to put bread on the table, if they owned one, before the advent of

a strong union.

And, for the Mexican national the Bracero Act brought little benefit and heaps of

heartache as the bill encouraged the common conviction of growers and ranchers that the

Mexican, in general, was disposable and replaceable due to the inherent authority gained

through the Bracero Act to utilize Mexican labor and send them home at their own

leisure and the idea of an unending government sanctioned supply cheap labor from south

17

44 Zeisler, Andi, Feminism and Pop Culture. (Seal Press, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008) 27-28. 45 London and Anderson, 1970, 14.

of the border.46 A fierce opponent of the Bracero Act, and similar bills, was renowned

scholar Ernesto Galarza who noted that these immigration for labor agreements were

contradicting their stated purpose of nurturing brotherhood and cooperation among

neighboring nations and were actually nurturing a social condition where “the larger

neighbor exploits the smaller.”47

Once the bracero was lured to the land of milk and honey with inverted promises

of El Dorado they were treated as private property of the landowner and grower, their

only source for food, housing, transportation and outside communication. Conditions

very indistinguishable from the harsh treatment and extreme control that early European-

Americans and immigrants had to contend with in the pre-union company towns of the

industrial age. Yet, as previously discussed, the living conditions of the bracero were far

more inhumane and extraordinarily substandard in comparison to their preindustrial

counterpart.48 And their compliance was understood to be unconditional under the threat

of deportation. Union organizers and religious representatives can recall how when

attempting to address bracero contract workers in the field the foreman would come by

an yell out, ¡al trabajo o a Mexico! /to work or to Mexico, as a threat that would surely

be fulfilled.49

In spite of all this, the group who most severely suffered from the

consequences of the Bracero Act was the farm working community of Mexicans who had

migrated into United States territory prior to or during the First World War or who had

18

46 Rubin, Rachel and Melnick, Jeffrey, Immigration and American Pop Culture: An Introduction. (New York University Press, New York, NY, USA, 200) 52-53. 47 London and Anderson, 1970, 117. 48 Porteous, J. Douglas, "Social Class In Atacama Company Towns," Annals Of The Association Of American Geographers, Vol. 64, No. 3, 1974, pp. 409. 49 Taylor, 1970, 67, 87; London and Anderson, 1970, 84.

resided in the region since its days as Nueva España. For this community the

disenfranchisement was two fold in that they lived in the same vile settings as the

bracero, either in the same ranch property encampments or on the fringes of town in the

aforementioned colonias and barrios of the Southwest, as well as deal with shady payroll

practices, if there was any payroll at all. The Mexican-American was also subjected to the

same issues of racism and second class treatment that the Mexican national had to deal

with because they were on e in the same in societies eyes.

The implementation and continual renewal and extension of the Bracero Act

contributed to degradating conditions that led to group unemployment, stagnant or

decreasing wages in the face of inflation and the further division of a community that was

once joined at the hip through culture and heritage as the influx of braceros and illegal

aliens foraging for economic asylum increased exponentially each year. It became a

battle of braceros. The braceros of the World War One era and their descendents who

were now citizens expected the rights guaranteed them through naturalization to be

observed, especially pertaining to preferential treatment over foreign nationals in regards

to job opportunities.50 This put the two groups in opposition to each other more than ever

before. The only solution in some peoples view was to stand up and organize.

19

50 Taylor, 1970, 68; Garcia and Grown, 2012, 87.

Fielders Choice: Making Moves

The economic and social environment of 1944, along with the patriarch of the

Gonzales family Claro’s resignation from his job in the mines of Midland drove the two

of the Gonzales brothers, Julio and ‘Chio,’ to follow in the footsteps of their eldest

sibling “Lito” and venture further into the fields of California with their father and follow

the seasonal crops into the San Joaquin Valley. The brothers were no strangers to the

demanding schedule and rigors of picking and pruning because as children, when they

weren’t shining shoes for the soldiers from the local military base, they worked in the

agricultural fields of Blythe. However, they had not yet experienced the lifestyle of a

migrant farm worker until their first excursion, which set them in the potato fields just

outside of Delano working beside German prisoners of war who were being used as a

supplemental labor force during WWII.51 From there they went to Hollister and Salinas

for the cotton harvest then they wrapped up the season in Fresno picking table grapes,

and then it was back to school in Blythe. Throughout this excursion they would be further

exposed to the social protocol between the jefe/boss-man and the peon/laborer, a protocol

that reflected the class structure and societal norms of the region and era. The following

year another Gonzales brother joined his siblings and father on the harvest trail picking

20

51 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview #1 with Tio Chio. Phone interview. February 19, 2014; Reiss, Jean-Michael. “Bronzed Bodies behind Barbed Wire: Masculinity and the Treatment of German Prisoners of War in the United States during World War II." Journal Of Military History 69, no. 2 (April 2005) 486; Gonzales Sr., Julio, 2013.

table grapes beginning in Fresno, continuing on to Gilroy, and finishing in Delano where

young “Lito” met and began to court a certain local Mexican girl by the name of Teresa

Fabela; sister to Helen Fabela, the future Mrs. Chavez.52

In the summer of 1946 “Lito” made the decision to relocate to Delano from

Blythe in order to start a family with Teresa whom he went on marry that same year, and

become a permanent fixture in the vineyards and orchards of the California grapevine.

The two would tie the knot while Lito and his brothers were working along the harvest

circuit in Salinas where Teresa drove up from Delano for the impromptu ceremony. She

was also with child, their first-born Bobby. One of the seeds of the connection to the

Chavez family tree had been planted.53

The remainder of the Gonzales family would soon trail right behind and join

“Lito” along with his newly developed family and the farm worker community in a

docile, marginalized existence, for the time being. After several more years of roaming

back and forth from Blythe to the San Joaquin valley Julio Gonzales ultimately made his

way to Delano, and in due course, he came upon the woman whom he would spend the

rest of his life with, Theresa Hernandez daughter of Santiago Hernandez of Guanajuato,

Mexico.54

Julio Gonzales and Theresa Hernandez were just two individuals who upon reaching

ninth grade equivalency opted to drop out and take life on full steam ahead by working

full time in the fields. Up until that time, Julio had traveled with the harvests throughout

the summer until school was back in session, then he would return to Blythe for the

21

52 Gonzales Sr., Julio, 2013. 53 Gonzales Sr., Julio, 2013. 54 Gonzales Sr., Julio, 2013.

routine substandard education. Life in Delano as a couple began for them in the late

forties when the Gonzales family rented a house next door to Librado Chavez and his

family, and just down the road from the Hernandez family who resided in a house

designed and built by the patriarch, Santiago Hernandez himself. The latter half of the

1940’s also brought small but significant changes to these families; Cesar Chavez would

return from his stint in the United States Navy, get married to Helen Fabela, and relocate

with his family via the assistance of Claro Sr. who loaned the Chavez family his personal

pick-up truck for the move to the house on Jackson Street in the Colonia55 of Sal Si

Peudes56 in San Jose, while the Gonzales’ would move into the former Chavez residence

next door.57 And, at the onset of the 1950’s Julio and Theresa would get married and start

a family of their own.58 Their nuptials took place back in Blythe for reasons that shall be

explained.

As 1950 approached the relationship between Theresa and Julio grew and

blossomed simultaneously with the orchards, and survived the petty jealousies and drama

that are entailed in a budding relationship, so both chose to make it official through the

sacrament of marriage. There was one problem, in mid-twentieth century Delano, and its

surrounding districts; it was illegal for a minor of fifteen years of age to marry, with or

without parental consent, and Theresa Hernandez just turned fifteen. Therefore at twenty

years of age, Julio did the only thing he could short of migrating back south of the border.

22 55 Colonia/barrio are Spanish colloquial terms for neighborhood. 56 Levy, 1975, 51; Taylor, 1975, 77. Sal Si Puedes/get out if you can is the colonia known for its rough life of poverty, gangs and dirt roads that trapped cars in the mud during the rainy season. Hence the name “get out if you can,” which also reflected the dogma of "If you think you can handle it, sal si puedes. Fight him in the street." 57 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview with Tio Chio #2 at Taqueria in Delano, California. Face to face, February 23, 2014. Richard Chavez, Cesar’s brother drove the truck for the move. 58 Gonzales, Johnny. Unpublished interview with Father. Phone interview, February 16, 2014; Gonzales, Julio, 2013.

He returned to Blythe with his fifteen-year-old fiancé Theresa, and his sister Zenaida who

served as a witness, where their marriage, some would say elopement, would be legally

recognized under the eyes of the law.59 Subsequent to the birth of their first son, one of

three, Julio and Theresa pulled up stakes and headed for the glitz and glamour of East

Los Angeles where they would start their own chapter of the Gonzales clan. But, that is

another story yet to be told.

23

59 Gonzales Sr., Julio, 2013; Gonzales, Lucio “Chio,” 2014.

A House Divided

In some respects the 1950’s are the portent to the turbulence and pandemonium

that resulted from societal changes of the 1960’s United States; Brown V. Board of

Education put a monkey wrench in the machinery of segregation and Rock ‘n’ Roll was

taking over popular music causing the older generation to fume. 60 The pent up anger that

had been building up for decades began to percolate in the fifties and boiled over in the

sixties encouraging those who would become future leaders to ascend and take action.

During this period individuals such as martin Luther King, Muhammad Ali, Larry Itliong,

and Cesar Estrada Chavez would utilize their past histories and hone their skills as

activists and organizers for the purpose of bringing about social changes that would

benefit the lives of everyday Americans in all parts of the nation.

For Chavez, his inauguration into the world of activism began when he became

acquainted with Fred Ross in 1952, the founder of the CSO, Community Service

organization. From there he went on to organize the NFWA, National Farm Workers

Association, which would later be renamed the United farm Workers Union. The first

boycott for Chavez would be against the rose growers of McFarland, a town just south of

Delano. Although it would be the grape strike of 1965, a strike started by the Filipino

farm workers and AWOC, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee headed by

Larry Iltliong. 61 “They (the Filipinos) were the ones that started the strike. They started,

24

60 Klarman, Michael J. Brown V. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Movement: Abridged Edition of "From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. (Cary, NC, USA: Oxford University Press, 2007) 55, 57; Altschuler, Glenn C. All Shook Up: How Rock “n” Roll Changed America. (Cary, NC, USA: Oxford Univerity Press, 2003) 5. 61 Levy, 1975, 95, 179, 182-186.

but Cesar wasn’t ready. But, he had to go in, he had to.”62 The 1965 boycott would ignite

a movement and a war in the fields of the Grapevine and beyond that would last until

1977. The Huelga63 was born.

The struggle that went on in the fields of the agricultural Mecca and the picket

lines across America morphed into a civil war in Delano and other surrounding farm

worker strongholds. A war that took place in the streets between Huelgistas and

Teamsters, as well as town residents and seasonal farm workers, generating stress and

strife among co-workers, friends, and neighbors. On top of that, this division affected all

facets of life, including personal and recreational behavior.

Similar to the experiences of the 1960’s United States Deep South when students

activists from SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and other

organizations converged in Mississippi and other regions to lend a hand to the African-

American communities involved in protests and demonstrations against Jim Crow and the

“Man,” the involvement and introduction of outsiders in Delano sometimes led to

confusion and hostility, because not only did the growers and ranchers considered these

individuals “outside agitators,”64 but town residence were sometimes of the same

opinion. “You know people that were for the union were in the bigger towns, cause they

didn’t really know what was going on around here.”65

25

62 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio” 1014. 63 Hornak, Kenneth Allen. Dictionary of Political Science and International Relations (English-Spanish Spanish-English): Diccionario de Ciencas Politicas y Relaciones Internacionales. Horsham, PA, USA: Editorial Castilla La Vieja, 2003;Huelga: call a strike (to) convocar una huelga, declararse en huelga, entrar en huelga. The term became synonymous with the farm worker movement. 64 Taylor, Ronald B. “Chavez and the Farm Law: Time Running Out in the Fields.” Nation, February 7, 1976. 65 Anonymous, interviewee. Interview with anonymous relative #1. Face to face, February 22, 2014.

As Xicano activists, seasonal workers on strike and civil rights devotees decided

to assemble in Delano and make it the epicenter of their cause the residents of the area

had to practice a certain level of tolerance for the outsiders. A tolerance that in some

situations was worn thin due to misconceptions and misunderstandings of the individuals

who had to struggle to make ends meet and live their day to day lives in the midst of a

fight for civil rights. “A lot of people didn’t want to stop working because they had to pay

their bills. And um, most of the people from the Huelga were from out of town.”66

These misunderstandings fostered a split between old friends and coworkers as

well, where the struggle often times came down to conflicts between seasonal workers

who supported the Huelga and permanent ranch hands that resided in Delano. “Your

uncle had to start carrying a gun with him and he had to pick up his workers and take

them to work in his truck because the Huelgistas67 would follow them and threaten them

and yell at them.”68 In many cases these Huelgistas were people who at one time worked

side by side with the ranch hands for years prior to the rise of the Huelga, but with the

rise of La Causa many were forced to choose sides; a choice that resulted in broken

friendships and a stressful neighborhood atmosphere.

The work environment was not the only area affected by the rise of La Causa.

Bar-B-Cues and family gatherings are a significant part of the life of many Americans,

and it is no different for the Mexican community. A weekend, or holiday, never passes

without a celebration, fiesta, or a group of friends congregating to let off some steam,

relax and enjoy food, music and companionship accompanied with the consumption of

26

66 Anonymous interviewee, 2014. 67 Huelgistas = Strikers/supporters of La Causa. 68 Anonymous interviewee, 2014.

their favorite libation. It was the latter of these that led to unsuspected friction often times

during the Huelga years, because the preferred beverage and top-selling beer of the day

happened to be manufactured, packed, and distributed by Teamster Union employees and

the Coors brewing Company.

Therein was where one of the problems lied, because “the Huelga had a big list of

boycotted goods…it could have been Coors beer. Yeah, but that was my dad’s

favorite,”69 and if you were of Mexican descent and chose to purchase and consume this

product Huelga supporters instantly branded you a traitor regardless of your life

experiences or where your loyalties lied,70 “You can’t bring that in here cause’ if they see

it in our trashcan we’ll get in trouble.”71

Still, at times some circumstances called for the bending of rules. As is common

in most wars, those caught in the crossfire make due to survive and often compromises

materialize in order to keep the peace, which was the state of affairs for local residents

during the Huelga years. “Yeah when we went over there (keen)72, when we went to go

visit, we would go to party, but they’re out there in the boonies. And we come with a case

of beer? Knock, knock, knock, (tapping a hand on the table) I’m here with the beer.”

“Don’t let nobody see it, but bring it in.”73

27

69 Ortiz, Henry. Unpublished interview with Cousin Henry. Face to face, February 22, 2014. 70 http://www.colorado.edu/studentgroups/MEChA/coors.htm 71 Ortiz, Henry, 2014. 72 The small town of Keen, California is where the United Farm Workers headquarters is located, and is also the site of the Cesar Chavez burial grounds and memorial museum La Paz. 73 Ortiz, Henry, 2014.

The King is Dead …

April twenty-third 1993, the news of the death of Cesar Chavez reverberated

through the fields of California, the hills and valleys of the American Southwest and

extended to the United States Eastern Seaboard. He was sixty-six years of age. In honor

of his life a celebratory march was held on April twenty-ninth that went from Memorial

Park to the United Farm Workers Union field office on the “Forty Acres” property in

Delano, California, recently declared a national landmark. The march brought mourners

and spectators from all walks of life to Delano totaling over thirty-five thousand in

attendance. Newcomers and veterans of the movement gathered and mourned side by

side with Xicanos, cholos, Hollywood celebrities, and civic and religious leaders hoping

to get a glimpse and say their farewells to an icon of the civil rights era. 74

Subsequent to the memorial numerous preparations had to be made in order to

accommodate the incoming multitudes that wished to pay their respects to the dearly

departed. Part of this groundwork consisted of providing shelter for those who covered

lengthy distances to attend the event. The solution to this dilemma was to house attendees

at various locations throughout Delano, so the Chavez family approached their long time

friend and supporter “Chio” Gonzales and asked for a much-needed favor. “They asked

me if I would be a host for some of the people.”75 He agreed and housed as many people

as his house would permit. Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero, the legendary Tex-Mex musician

and an icon in his own right,76 was one of the honored houseguests. Unfortunately for

28

74 Morrison , Patt, and Mark Arax. “For the Final Time They March for Chavez.” Los Angeles Times. April 30, 1993. 75 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview with Tio “Chio” #4. Phone interview, April 12, 2014. 76 Avant-Mier, Roberto. Rock the Nation: Latino/a Identities and the Latin Rock Diaspora. (New York, NY, USA: Continuum International Publishing, 2010) 60-61.

“Lalo” and the thousands who turned out for the event, he would remain at “Chio’s”

house and not make an appearance at the march due to a sudden bout of fever. But, this

did not entirely damper his mood and afterwards “Lalo” was seen to be in better spirits.

“When we got back to house he was playing the guitar and singing with your uncle

“lito,.”77 the same uncle who was brother in-law to Cesar Chavez through the marriage of

Theresa Fabela.

On the day of the march sorrow filled, humbled masses congregated among the

springtime blossoms of the Grapevine, where countless numbers headed to several of

Delano’s landmark locations for the purpose of mobilizing for their final journey with the

famed civil rights leader. The Peoples’ Market with its adjoining pool hall/cantina on

Garces Highway and the domicile of prominent Delano resident Lucio “Chio” Gonzales

were two of these locations. “Chio,” the proprietor of above said locations and the only

son of Claro Gonzales who would choose the quiet rural life of Delano over the hustle

and bustle of Los Angeles that his siblings opted for. At these two settings relatives,

friends and neighbors, and an abundance of educators, politicians, union leaders and

Hollywood heavies like Richard “Cheech” Marin, Edward James Olmos, Jimmy Smits

and Paul Rodriguez joined members of the Gonzales family while in wait for the main

event of the morning.78

While the March got under way a plain, rectangular pine box lacking adornments

or inscriptions of any kind was brought to the forefront of the multitudes. It was the

casket that carried Cesar’s remains. Some may have said that such a modest casket was

29

77 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio,” 2014. 78 Gonzales, Johnny. Unpublished interview with Father. Phone interview, February 16, 2014; Gonzales, Lucio “Chio,” 2014.

unworthy of the man and the occasion, however it was constructed and designed

according to the explicit request and insistence of Cesar Chavez for he wished to

maintain his trademark lifestyle of piety and self-deprivation until the end so as to remain

in solidarity with those who he represented in his life’s struggle. It was a lifestyle of

humility and non-violence modeled in the fashion of Mahatma Gandhi who was by no

small coincidence a major influence on another well-known Civil Rights leader, Martin

Luther King Jr. Chavez’ meek way of life was evident in the fact that he only ever earned

no more than five thousand dollars a year in his life, “but that’s not all watch this. Cesar,

he never owned a suit…Cesar never owned a house, never owned a house…never owned

a car,”79 this permitted him to remain mobile and accessible to union members and the

public since throughout the struggle he was often housed by individuals from these two

groups, as well as members of his extended family.80

To further reinforce this ideal on the solemn occasion Richard Chavez, Cesar’s

brother, made the decision to include individuals from the disenfranchised and

impoverished communities that looked to the movement for economic solace and shelter

from injustice in the task of constructing the casket. According to “Chio,” it was

Richard’s opinion that by allowing these individuals to participate in such a momentous

task they would not only build a proper casket for his brother but also build an everlasting

personal bond with American history and the movement.81

As the mass of mourners mingled with one another and energetic new faces

greeted and paid respect to timeworn old ones, the electricity of the gathering changed to

30

79 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio,” 2014. 80 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Interview #3 with Lucio at pool hall. Face to face interview, February 24, 2014. 81 Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.,” 2014.

one of rejoicing and fellowship. It was during this time of momentary elation when

several UFW volunteers began to distribute handmade, impromptu versions of the United

Farm Workers banner to those in attendance that could be reached before the supply of

flags was diminished. Each flag was a portion of cotton fabric of either red or white in

color and cut to the dimensions of approximately nineteen by sixteen inches. “In Memory

of Ceasar82 Chavez April, 29, 1993” was inscribed on the bottom left hand corner of each

flag, and in the center the image of the black eagle was unevenly spray-painted using a

makeshift template.83 The black eagle is the symbol of the United Farm Worker Union

that was designed by Cesar’s cousin Manuel Chavez. Julio Gonzales was given a red

banner and his eldest son, Johnny Gonzales, received a white version, additionally

relatives of the deceased were given commemorative pins that read, “Brothers And

Sisters Join Our Struggle: Demand Union Label” with a red ribbon attached for the

purpose of distinguishing family members from among the general crowd of observers

and attendees. Each of these artifacts is still in family possession, although they are now

tattered and worn.84

The flags were handed out at the Memorial March to be displayed as a symbol of

solidarity demonstrating that the union would continue to thrive and survive, and also as

another method of expressing appreciation to, while at the same time including, the

multitudes who participated in and supported La Causa throughout the years. It was

through this process and Richard’s decision with the construction of his brother’s casket

31

82 Spelling of name on artwork. 83 Morrison and Arax, 1993. 84 Unknown volunteer. United Farm Worker Flag; Black on white. Cotton Fabric, 19’ x 16’, April 29, 1993; Unknown. Cesar Chavez Memorial Service: Commemorative Pin and Ribbon. Pin, 1’ 1/2' diameter, April 29, 1993.; Gonzales, Johnny, 2014.

that the Chavez family and the United Farm Workers Union hoped to lend and share a

personal connection to Cesar and La Causa with the common farm worker, as well as

with the activists, celebrities and anonymous bystanders in attendance.

For many people the memorial march was considered an end to an era, but others

anticipated that it was the dawning of a new age of activism and a rebirth of the

movement, “Hopefully this isn’t just for the moment.”85 Yet, for those who knew him

personally and intimately, either through familial relations or as supporter of La Causa,

Cesar Chavez would be remembered as the protector of the meek and defender of the

faithful. And, to some, “he was the greatest man on earth, that I knew,”86 plain and

simple.

32

85 Morrison and Arax, 1993, A30. 86 Gonzales, Lucio, “Chio,” 2014.

Conclusion

Grand occasions and large personalities are most commonly translated in history

as the end all and be all of the events they describe, however it is the involvement,

directly or indirectly, of the common individual that makes these stories and

accomplishments possible and a reality. The fact that the UFW and La Causa were based

out of Delano, California reflects the way we view and interpret the lives of those who

live in the area as simply farm workers. By doing this we overlook the intricacies of the

events and individual personalities of the people who made a difference for themselves

and influenced those around them. These interpretations often lead to stereotypes and

generalizations. Yet, It is through the support and actions of the small, yet key players, in

the great scheme of life that great things happen, and not always the way we imagined

them.

Nos vemos pronto en los campos; See you soon in the fields.

33

Appendix A: Interview Consent Form

University of Hawai’i

Consent to Participate in Research Project: Delano: The Little Town That Did Big Things

My name is John Gonzales. I am an undergraduate student at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa pursuing a double major in the fields of anthropology and history. In accordance with my history major I am currently working on a research project in order to complete the qualifications for a degree in that field. The project is an historical account of the journey of the Mexican migrant farm worker of the American Southwest in relation to Delano, California and the development of United Farm Workers Union. I am asking you to participate in this project because you and/or your immediate relatives have, or had, direct experience with these events. Activities and Time Commitment: If you agree to participate in the project, I will conduct casual and informal interviews with you at your convenience either in person or by phone. The interviews will last only as long as you wish them to. These interviews will be recorded with a digital audio recorder and hand written journal notations. The questions will be basic and generalized because their purpose is to obtain your personal insights and recollections of the entire period. Copies of the finished project will be sent to all those who participate. The number of participants will vary from six to nine, depending on availability of interviewee. The interviews will be used in compiling a concise historical account of the journey of the Mexican migrant farm working community in Delano and the social issues of the period that effected their livelihood and existence. In the future, this study may segue into a greater examination of the area and contribute to later research. Confidentiality and Privacy: I will keep all information from interviews in my possession at all times, however the University of Hawaii Human Studies Program has the right to review research records for this study. For the purpose of accuracy in documenting these historic events, it is important that your name appear as the interviewee on the transcript, but you will retain the right to delete, add or amend information in the transcripts and audio recordings. Once the project is completed I will either destroy the audio recordings, or put them in the possession of the interviewees if desired. Benefits and Risks:

34

There is no direct benefit for you in the participation of this project, yet you will be contributing to the historical recording and account of the described era that this project is attempting to offer. I do not believe there is any risk to you in participating in this study, but you may feel uncomfortable answering any of the interview questions or discussing certain topics during the interview. If at any time you feel uncomfortable due to the resurgence of unpleasant memories or topic matters you can terminate participation in the project immediately and receive your portion of the interviews for personal keeping or disposal, or skip said topics altogether and continue with the interview. However, your anonymity cannot be guaranteed because your name will appear in the interview transcripts, but not in the written project if so desired. Voluntary Participation: Your participation in this research project is voluntary and you are free to end or withdrawal from your participation at any time without any consequences. You will also receive a recording and/or transcript of your interview via airmail, or email if possible, prior to the completion of the project for reviewing and editing purposes. Questions: Please feel free to contact me, John Gonzales, at (808) 953-0339 if you have any questions regarding this project. If you have questions about your rights as a research participant, contact the UH Committee on Human Studies at (808) 956-5007 or via email at, [email protected] Interview Process: In your participation you will have a choice of how the interview should be recorded. If you chose audio recording then I will provide the instrument for the process. However, if you prefer hand written notes or an informal interview without on the spot recording, than you will be accommodated as well.

Agreement to Participate in

Delano: The Little Town That Did Big Things “I certify that I have read and understand the information in this consent form, and that I have been told that I am free to withdraw my consent and to discontinue participation in the project at any time without any negative consequences to me.

I herewith give my consent to participate in this project with the understanding that such consent does not waive any of my legal rights.”

_____________________________ _________________________________ Printed Name of Interviewee Signature of Interviewee ______________________ Date

35

Bibliography

Primary Sources: -Anonymous Interviewee. Interview with anonymous relative #1. Face to face, February 22, 2014. -Gonzales, Johnny. Unpublished interview with Father. Phone interview, February 16, 2014. -Gonzales Sr., Julio. Unpublished interviewed with Grandfather #1. Phone interview, December 16, 2013. -Gonzales Sr., Julio. Unpublished interview with Grandfather #2. Phone interview, April 14, 2014. -Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview #1 with Tio Chio. Phone interview. February 19, 2014. - Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview #3 with Lucio at pool hall. Face to face interview, February 24, 2014. -Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview with #2 Tio Chio #2 at Tampico Taqueria. Face to face, February 23, 2014. -Gonzales, Lucio “Chio.” Unpublished interview with Tio “Chio” #4. Phone interview, April 12, 2014. -Ortiz, Henry. Unpublished interview with Cousin Henry. Face to face, February 22, 2014. -Unknown volunteer. United Farm Worker Flag; Black on white. Cotton Fabric, 19’ x 16’, April 29, 1993. -Unknown. Cesar Chavez Memorial Service: Commemorative Pin and Ribbon. Pin, 1’ 1/2' diameter, April 29, 1993.

Additional Sources: -Altschuler, Glenn C. All Shook Up: How Rock “n” Roll Changed America. Cary, NC, USA: Oxford Univerity Press, 2003. -Avant-Mier, Roberto. Rock the Nation: Latino/a Identities and the Latin Rock Diaspora. New York, NY, USA: Continuum International Publishing, 2010. -Babb, Sanora, Dorothy Babb, and Douglas Wixson. On the Dirty Plate Trail: The Dust Bowl Refugee Camps. Austin, TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 2007. -Bender, Steven, W., Greasers and Gringos: Latinos, Law, and the American Imagination, New York University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2003.

36

-Bierhorst, John. Ballads of the Lords of New Spain: The Codex Romances de Los Señores de La Nueva España. Austin, TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 2009. -Botero, Rodrigo. Ambivalent Embrace: America’s Relations with Spain from the Revolutionary War to the Cold War. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Press, 2000. -Burrill, Donald R. Servants of the Law: Judicial Politics on the California Frontier, 1849-1889. Blue Ridge Summit, PA, USA: University press of America, 2010. -Donato, Ruben, and Jarrod S. Hanson. “Legally White, Socially ‘Mexican’ The Politics of De Jure and De Facto School Segregation in the American Southwest.” Harvard Educational Review 82, no. No. 2 (Summer 2012): 202–225. -Garcia, Ignacio M. Hispanic Civil Rights Series: Hector P. Garcia: In Relentless Pursuit of Justice. Houston, Texas, USA: Arte Publico Press, 2002. - Garcia, Ruben and Grown, Caren, Marginal Workers: How Legal Default Lines Divide Workers and Leave Them without Protection, New York University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2012. -Gore , Dayo F., Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodward. Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. New York, NY, USA: New York University Press (NYU Press), 2009. -Hornak, Kenneth Allen. Dictionary of Political Science and International Relations (English-Spanish Spanish-English): Diccionario de Ciencas Politicas y Relaciones Internacionales. Horsham, PA, USA: Editorial Castilla La Vieja, 2003. -kirkwood, Burton. History of Mexico. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Press, 2000. -Klarman, Michael J. Brown V. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Movement: Abridged Edition of "From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. Cary, NC, USA: Oxford University Press, 2007. -Kushner, Sam. Long Road To Delano. First Edition. New York, USA: International Publishers Co., Inc., 1975. -Leiter, Andrew B. Southern Literary Studies: In the Shadow of the Black Beast: African American Masculinity in the Harlem and Southern Renaissance. Baton Rouge, LA, USA: Louisiana State University Press (LSU Press), 2010. -Levy, Jacques E., Cesar Chavez: An Autobiography of La Causa, 1st ed. New York: Norton Publishing, 1975. -London, Joan, and Henry Anderson. So Shall Ye Reap. New York, USA: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1970.

37

-Mazon, Mauricio. The Zoot-Suit Riots: The Psychology Of Symbolic Annihilation. Austin, TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 1984. -Montejano, David. Quixote’s Soldiers: A Local History of the Chicano Movement 1966-1981. Austin, Texas, USA: University of Texas Press, 2010. -Moraga, Cherrie. Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness: Writings, 2000-2010. Durham, NC, USA: Duke University Press, 2011. - Morrison , Patt, and Mark Arax. “For the Final Time They March for Chavez.” Los Angeles Times. April 30, 1993. -Murphy, Gretchen. Shadowing the White Man’s Burden: U.S. Imperialism and the Problem of the Color Line. New York, NY, USA: New York University Press (NYU Press), 2010. -Nadaillac, Marquis De , and John Muller. Prehistoric America. Tuscaloosa, AL, USA: University of Alabama Press, 2005. -Orozco, Cynthia E. . No Mexicans, or Dogs Allowed: The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. Austin TX, USA: University of Texas Press, 2009. -Ozsvath, Zsuzsanna, and David Patterson. When the Danube Ran Red. Syracuse, NY, USA: Syracuse University Press, 2010. -Peiss, Kathy. Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style. Philadelphia, PA, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. -Perreira, Randy. “Hawai’i State AFL-CIO President, Letter: Workers Still Stand Against Walgreens.” The Hawai’i Independent, April 2010. http://hawaiiindependent.net/story/letter-workers-unions-still-standing-against-walgreens. -Perez, Louis A. War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. - Porteous, J. Douglas, "Social Class In Atacama Company Towns," Annals Of The Association Of American Geographers, Vol. 64, No. 3, 1974, pp. 409-417. -Raferty, Miriam. “Shame On Walgreen’s: Labor Dispute Takes to the Streets.” East County Magazine, September 2010. http://www.eastcountymagazine.org/node/4293. -Rivera, John-Micheal. Emergence of Mexican America: Recovering Stories of Mexican Peoplehood in U.S. Culture. New York, NY, USA: New York University Press, 2006.

38