Infections in the Elderly Hans Jürgen Heppner, MD, MHBA a,b, *, Sieber Cornel, MD b , Walger Peter, MD c , Bahrmann Philipp, MD b,d , Singler Katrin, MD b,d BACKGROUND The western concepts of infection pathogenesis begin with Hippocrates, who saw the dysregulation of the 4 body humors as the cause of disease. 1 In antiquity, Galen of Pergamon (the famous physician Claudius Galenus) was already practicing abscess drainage. In founding the modern age of infection management, Semmelweiss, Lister, Pasteur, Koch, Flemming, or Paul Ehrlich contributed major innovations in infection concepts. 2–6 Later, the so-called “Taragona strategy,” 7 themed “hit hard and early,” was developed base d on the ideas of Paul Ehrli ch, who pro posed “fra pper fort et fra p- per vite”. 8 For all authors there is no conflict of interest. H.J. Heppner has received speaker’s fees from Pfizer, MSD, Astellas, and Bayer Health Care and is a research fellow of the “Forschungskolleg Geriatrie,” Robert Bosch Foundation, Stuttgart, Germany. a D ep ar tm en t of E me rg en c y a nd I nt en si ve C ar e M ed ic ine , K li ni ku m N ur em be rg , Prof.-E.-Nathan-Str. 1, Nuremberg D-90419, Germany; b Institute for Biomedicine of Aging, Friedrich-Alexander-Uni versit y Erlangen-Nuremberg, Heimerichstr. 58, Nuremberg D-90419, Germany; c Depatment of Intensive Care Medicine, Johanniter Hospital Bonn, Johanniterstr. 3-5, Bonn D-53113, Germany; d Department of Acute Geriatric Medicine, Klinikum Nuremberg, Prof.-E.-Nathan-Str. 1, Nuremberg D-90419, Germany * Corresponding author. Department of Emergency and Intensive Care Medicine, Klinikum Nuremberg, Prof.-E.-Nathan-Str. 1, Nuremberg D-90419, Germany. E-mail address: [email protected] KEYWORDS Infections Elderly Immune senescence Geriatric Sepsis Pneumonia Functional decline KEY POINTS Infectious diseases are very common in the elderly and there is an increasing morbidity and mortality in old age. The occurren ce and cours e of infecti on depends, in part, on immu ne senescenc e, func- tional status, and self-independence in daily living. Appropriate and rapid initiation of supportive care and antimicrobial therapy is crucial for outcome. Crit Care Clin 29 (2013) 757–774 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.016 criticalcare.theclinics.com 0749-0704/13 /$ – see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc. All right s reserved.

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 1/18

I n f e c t i on s i n t h e E l d e r l y

Hans Jürgen Heppner, MD, MHBAa,b,*, Sieber Cornel, MD

b,

Walger Peter, MDc, Bahrmann Philipp, MDb,d, Singler Katrin, MDb,d

BACKGROUND

The western concepts of infection pathogenesis begin with Hippocrates, who saw the

dysregulation of the 4 body humors as the cause of disease.1 In antiquity, Galen of

Pergamon (the famous physician Claudius Galenus) was already practicing abscess

drainage. In founding the modern age of infection management, Semmelweiss, Lister,

Pasteur, Koch, Flemming, or Paul Ehrlich contributed major innovations in infection

concepts.2–6 Later, the so-called “Taragona strategy,”7 themed “hit hard and early,”

was developed based on the ideas of Paul Ehrlich, who proposed “frapper fort et frap-

per vite”.8

For all authors there is no conflict of interest. H.J. Heppner has received speaker’s fees fromPfizer, MSD, Astellas, and Bayer Health Care and is a research fellow of the “ForschungskollegGeriatrie,” Robert Bosch Foundation, Stuttgart, Germany.a Department of Emergency and Intensive Care Medicine, Klinikum Nuremberg,Prof.-E.-Nathan-Str. 1, Nuremberg D-90419, Germany; b Institute for Biomedicine of Aging,Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Heimerichstr. 58, Nuremberg D-90419,Germany; c Depatment of Intensive Care Medicine, Johanniter Hospital Bonn, Johanniterstr.

3-5, Bonn D-53113, Germany;

d

Department of Acute Geriatric Medicine, Klinikum Nuremberg,Prof.-E.-Nathan-Str. 1, Nuremberg D-90419, Germany* Corresponding author. Department of Emergency and Intensive Care Medicine, KlinikumNuremberg, Prof.-E.-Nathan-Str. 1, Nuremberg D-90419, Germany.E-mail address: [email protected]

KEYWORDS

Infections Elderly Immune senescence Geriatric Sepsis Pneumonia Functional decline

KEY POINTS

Infectious diseases are very common in the elderly and there is an increasing morbidityand mortality in old age.

The occurrence and course of infection depends, in part, on immune senescence, func-

tional status, and self-independence in daily living.

Appropriate and rapid initiation of supportive care and antimicrobial therapy is crucial for

outcome.

Crit Care Clin 29 (2013) 757–774http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.016 criticalcare.theclinics.com

0749-0704/13/$ – see front matter 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 2/18

Nonetheless, infectious diseases are still the leading cause of death in the elderly.

Due to demographic shifts, the number of elderly patients treated for serious infections

is increasing. Infections of the urinary tract and the lower respiratory tract (LRTI) domi-

nate in the geriatric population. Although LRTI infections are reported to be the third

leading cause of death worldwide, they are of particular importance in the geriatric

population.9 Sir William Osler wrote, “pneumonia may well be called the friend of

the aged” more than 100 years ago.10 Infections have a high mortality rate in this pa-

tient group. The susceptibility to infection in the elderly is increased by immune senes-

cence as well as altered skin and mucosal barrier function.11

THE GERIATRIC PATIENT

Aging and disease must be distinguished. Aging leads to a reduction in the adapt-

ability of the body to daily requirements, but is not itself a disease.12 Age-related

changes in health and age-correlated disease processes condition one another.

Current demographic trends clearly show that the proportion of elderly patients in all

stages of care is increasing in most of the developed world. This increasing trend is

changing the challenges facing global health systems. The management of infectious

diseases in geriatric patients in relation to their multiple comorbidities, impending dis-

abilities, and functional impairments is a unique challenge. Typically age-related loss

of adaptability (see the definition in Box 1 ) of the body influences the occurrence,

course, and prognosis of infectious diseases. During the physiologic aging process,

various organ systems are affected that are important for response to infection. Struc-

tural and functional changes take place in the organ systems, which modify patients’

immune and defense status13 and physiologic stress response. Stress and age-

related alterations in body composition and metabolism can alter the pharmacoki-

netics and pharmacodynamics of anti-infectives. Comorbidities, functional status of

the patient, and attitude to quality of life are of fundamental importance in the elderly

in particular. Various patient groups must be distinguished: those that are consider-

ably more agile than may be expected based on calendar age should be distinguished

from those that are frail or already dependent on care and can therefore fall back on

Box 1

Definition of geriatrics and geriatric medicine of the European Union of Medical Specialists—

Geriatric Medicine Section (UEMS-GMS), Malta, May 2008123

Geriatric patients are defined by:

Multimorbidity and

More advanced agea (predominantly 70 years or older)

a Multimorbidity (chronic comorbidities) typical of geriatrics is in this context to be regardedas taking priority over calendar age;

Or merely by age 80 years or olderb

b Owing to typically age-related increased vulnerability, for example, due to

The occurrence of complications and sequelae,

The risk of progressive chronic illness, and

The increased risk of loss of autonomy with a deterioration in self-help status

Data from Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, et al. Guidelines for the management of adult lowerrespiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J 2005;26(6):1138–80.

Heppner et al758

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 3/18

more modest physical reserves in the case of acute infections (also see Box 2 ).

Studies have demonstrated that the prognosis for severe infections, particularly in

geriatric patients more than 80 years of age, is clearly linked to functional status.14

In age-matched groups of patients, the residential environment (whether resident in

own household or an institutionalized care facility ) is associated with the microbiolog-

ical etiology of the infections and mortality risk.15 If the degree of activity is compared

with the aid of various geriatric assessments, such as activity of daily living scores or

the Barthel index, the patient group presenting the highest functional deficit has

increased risk of infections with Staphylococcus aureus or gram-negative bacilli.16

SPECIFIC FEATURES OF INFECTIONS IN ELDERLY SUBJECTS

Impairment of the functional status of the patient promotes age-related changes in the

immune system and, as a consequence, the occurrence of infections. External factors

such as degenerative changes in bone and cartilage that reduce thoracic mobility and

consecutively hamper respiratory work also play a role. The decrease in vital capacity

and the impairment of pulmonary function17 also influence the course of respiratory

tract infections adversely. With an increasing loss of independence and daily skills,

the spectrum of pathogens shifts toward S aureus and gram-negative bacilli, including

Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

With advancing age, infections are increasingly frequent as a cause for inpatient

hospital admission or presentation to an emergency department; this applies to

patients from long-term care establishments18 and to patients from the domestic envi-

ronment. The consequence is an increase in the prescription of antimicrobial sub-

stances in geriatric patients with all adverse consequences.19

THE AGING IMMUNE SYSTEM

The aging process is accompanied by qualitative and quantitative changes in the im-

mune system. With increasing age, overall immune response becomes less efficient,

less appropriate, and occasionally harmful. Within this dysfunctional process, immune

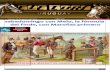

dysfunction alters the response to infection in older people ( Fig. 1 ). This process, also

called immunosenescence, is characterized by profound changes in T-cell subsets,

antigen recognition repertoires, and effector functions. Aging also has a significant

impact on the production of circulating cytokines and the circulating cytokine milieumay contribute to the development of age-restricted conditions.20 For example,

Box 2

Causes of increased susceptibility to infection and secondary complications in geriatric

patients

Morbidity and mortality risks of infections in elderly subjects

Reduced functional reserves

Modified pathogenic spectrum

Reduced defense mechanisms

Repeated/multiple hospital stays

Delayed diagnosis and initiation of therapy

Delayed response to antibiotics

Increased occurrence of adverse drug reactions

Infections in the Elderly 759

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 4/18

altered antibody production increases fatality from pneumonia. T-cell proliferation and

expression are also reduced in old age, conditioned by thymus involution, and the

effector cells are of less function.21 Elderly humans are more susceptible to bacterial

infections because of declining immune status and this effect depends on a decreaseof neutrophil function and reduced neutrophil CD16 expression and phagocytosis.22

This immune senescence also has other clinical consequences, such as impaired

response to vaccination,23 contributing to the development of age-associated degen-

erative diseases. On the potentially beneficial side, immunoglobulin E–mediated

hypersensitivity reactions are less frequent and allergic symptoms tend to improve

with age.

CHRONIC COMORBIDITIES (MULTIMORBIDITY)

The geriatric patient is characterized by chronic comorbidities/multimorbidity, whichmeans the simultaneous existence of multiple chronic conditions requiring medical

therapy. The number of chronic conditions increases with increasing age; on average,

3 to 9 concomitant conditions (diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, osteoporosis,

incontinence, chronic bronchitis, heart failure, impairment of cognitive performance,

etc) are to be expected, which inevitably increases the risk of complications and,

partially as a result, morbidity and mortality from most infectious diseases increase

with ascending age. The most prominent comorbidities triggering infections are dia-

betes mellitus and chronic heart failure.24,25 Assessments to evaluate the current func-

tional status or decline are necessary to accurately assess severity of infection and

prognosis. The bodily changes in older age are best described by the terms “frailty”and “sarcopenia.”

FRAILTY

“Frailty” is a set of symptoms reported in the elderly that describes the vulnerability of

the aging body due to various endogenous and exogenous mechanisms.26 Frailty

rise of morbitity and mortality

immune

dysfunction

impaired immune

defense

increased

sensitivity to

pathogens

increased

infection risk

increased

susceptibilityto

cancer

autoimmune-

diseases

chronic

inflammationleading to

atherosclerosis

osteoporosis

diabetes mellitus

arthritis

vaccination

decreased

antibody

response

immunesenescence and potential consequences

Fig. 1. Consequences of immune senescence.

Heppner et al760

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 5/18

should best be described in accordance with Fried and colleagues’ criteria.27 Closely

connected with frailty syndrome is sarcopenia, the pronounced loss of muscle power

and muscle mass in the elderly.28 Frailty as an autonomous geriatric syndrome is

associated with a less robust response in the elderly patient to stress, injury, and acute

diseases, which may be detrimental. In infections of geriatric patients, frailty is asso-

ciated with a course comprising multiple complications, more difficult convalescence,

and higher mortality. Inflammatory processes of low intensity take place continuously

as part of the frailty syndrome.29 Independently of the underlying condition, changes in

blood clotting activity and often anemia accompany the frailty syndrome.30 Certain

laboratory parameters can be used to support the early diagnosis of frailty.31 However,

in patients who fulfill the frailty criteria, acute phase proteins such as C-reactive protein

(CRP) are increased, which may hamper the diagnosis of an acute infection. The same

applies to interleukin-6.32 In acute diseases, susceptibility to infections is increased

due to the catabolism-induced loss of muscle mass and functional proteins. Increased

levels of inflammatory cytokines, as exist in frailty syndrome, are associated with

increased mortality in connection with acute infections.33

SARCOPENIA

Physiologic aging leads to the loss of skeletal muscle mass and thereby to reduced

muscle strength and reduced regeneration capacity34 after acute disease events.

From about the 50th year of life, approximately 1% to 2% muscle mass is lost each

year, and analogously around 1.5% muscle power, with this rate of loss increasing

further from the 60th year of life. About 5% to 10% of the elderly overall and about

one-half of those over 80 years of age are affected with sarcopenia occurring about

twice as frequently as frailty.35 The diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia are listed in

Table 1. Consideration of sarcopenia plays an important role in dealing with and treat-

ing patients, and also in the prevention of functional loss.36 Irrespective of the under-

lying disease, sarcopenia is an independent risk factor for mortality.37

DIAGNOSIS

The symptoms of acute infections in the geriatric patient are generally nonspecific.

Clinical manifestations of infection in this patient group are often atypical. In LRTIs,

the “classical” symptoms, such as fever, chills, or cough or expectoration, are

frequently missing. In the elderly, dyspnea without other major signs and symptoms

is not uncommon. A reduced or even nonexistent fever reaction—even in the case

of severe respiratory tract infections—hampers diagnosis. The reason for this failure

Table 1

Diagnosis criteria for sarcopenia

Diagnostic Criterion Scope for Diagnosis

Low muscle mass DEXAa, BIAb

Low muscle power Hand strength measurementLow physical capacity Walking speed <0.8 m/s

2 of 3 criteria must be fulfilled for diagnosis

a Dual Energy x-ray absorptiometry.b Bioimpedance analysis.

Data from Barbieri M, Ferucci L, Rango E, et al. Chronic inflammation and the effect of IGF-1 onmuscle strength and power in older persons. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003;284:E481–7.

Infections in the Elderly 761

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 6/18

to generate a febrile response resides in impaired heat conservation and changes in

central temperature regulation. In about 20% of cases of pneumonia, elderly patients

do not exhibit cough, and in 25% to 50% of cases, fever is absent.38

Body temperature is usually central in the diagnosis of infection. However, in older

subjects, body temperature is lower than that of younger people and their tolerance

of thermal extremes is more limited. The average core body temperature difference be-

tween a clinically healthy adult (ages 20–64) and an elderly person (ages 65–95) is

approximately 0.4C/0.7F. For the elderly, 37.2C/98.9F and not 38.0C/100F as in

younger adults can be considered to represent a febrile response. A different fever cut-

off for patients 75 years and older39,40 with possible infection is required because an

inadequate cutoff level might lead to a delay in diagnosis and initiation of treatment.41

Instead of infectious signs typical of younger patients, elderly patients often exhibit

atypical presentations including new onset confusion, acute deterioration of mobility,

and subtle disturbances of circulatory regulation (hypotension and lactic acidosis

without overt toxemia or tachycardia).42 Laboratory inflammatory markers are also

often initially absent or only minimally abnormal in the geriatric infected patient so

that anti-infective therapy is often started only in a delayed fashion.43

Whenever there is a reasonable suspicion for an infection, a laboratory-based diag-

nostic evaluation is crucial. Sputum can be taken, but the value of a sputum culture is

limited. Culture of other sites can also be useful. Blood cultures should be performed to

assess bacteremia/fungemia. Recommendations for the use of a urine antigen test are

conflicting.44,45 British guidelines recommend testing for Streptococcus pneumoniae44

to reduce broad spectrum antibacterials in patients with community-acquired pneu-

monia.46 German guidelines do not recommend this antigen testing as necessary,45

because an empiric therapy should always cover S pneumoniae as a possible pathogen.

VALUE OF BIOMARKERS IN DETECTING INFECTIONS IN THE ELDERLY

Radiological changes of the lungs in geriatric patients with pneumonia are frequently

nonspecific and do not always reflect the acute status.47 Given pre-existing comorbid-

ities, infiltrative changes of the lungs may persist for months. The new onset occur-

rence of the principal symptom of dyspnea, clinical suspicion of infection, and

exclusion of other major cardiac or pulmonary comorbidity is crucial. However, an

initially erroneous diagnosis in the emergency admission unit leads to incorrect initial

therapy and thus to a poorer patient prognosis.48 For that reason, inflammatorymarkers may be useful.

The inflammatory parameters, CRP and procalcitonin (PCT), are helpful for the diag-

nosis of bacterial infection.49,50 They are useful for predicting the short-term prognosis

of patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).51 Applicability to geriatric pa-

tients has not yet been clearly established. CRP and the white cell count, like clinical

signs and symptoms, are not always reliable parameters in geriatric patients because

they may occasionally fall in the normal range (especially in the elderly). Although the

inflammatory parameters CRP, PCT, and white cell count are highest whereby a bac-

terial process (in contrast to atypical or viral processes) is involved in the infection,

these markers do not always permit individual differentiation. PCT is nevertheless suit-able in estimating severity and prognosis of CAP.51,52 The risk of bacteremia in

connection with pneumonia can also be estimated by this marker.51,53 The targeted

use of biomarkers directly on admission of the patients, such as PCT or N-terminal-

proBrain natriuretic peptide, which is a sensible marker for acute cardiac decompen-

sation, can help to avoid therapeutic delay and treatment delay-associated secondary

complications.

Heppner et al762

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 7/18

DELIRIUM AND INFECTION

Acute confusion or disturbance of consciousness is one of the common atypical (rela-

tive to nonelderly) primary manifestations of infection in geriatric patients. Infections

are one of the commonest causes of acute disturbances of consciousness in the

elderly. The prevalence of delirium of any cause in the elderly is high; cumulatively14% to 56% in inpatients54 and 10% to 30% at any time during an inpatient stay.55

Among elderly patients with cancer, 25% to 55% of patients who are asymptomatic

on admission become delirious during the stay in the hospital.56 In an analysis of 73

consecutive acute admissions of patients older than 70 years with impaired con-

sciousness, the proportion of infections as a triggering cause was 34.3%. Fifty-eight

percent of the 64 patients contracting pneumonia as part of a reported legionella

outbreak presented with acute encephalopathy, predominantly hypoactive delirium.57

A few were even admitted with a primary neurologic diagnosis rather than as pneu-

monia. In the S3 guidelines for CAP (based on the CURB-65 score), symptoms of

delirium (C 5 confusion) are 1 of 4 criteria that necessitate the inpatient admission.58In the absence of fever, delirium may frequently be the only symptom with which an

acute infection manifests itself in elderly patients. In a Swedish study of 504 outpatient

women older than 85 years, a urinary tract infection (UTI) was present in 17.2% (87/

504), of which 44.8% (39/87) concomitantly had acute delirium. In total, 27.2% (137/

504) had symptoms of delirium, of which 28.5% concomitantly had a UTI within the pre-

vious month. In a multivariate regression analysis, a UTI was significantly (OR 5 1.9)

associated with delirium.59 Infections are a very common cause of delirium in the

elderly, but various other reasons for delirium may also be found.60 Delirium is a

frequent primary reason for admission for elderly patients. Missed or delayed diagnosis

and anti-infective therapy for infection as a result of atypical presentation with confu-sion/delirium can lead to longer hospital admissions, an increased risk of nosocomial

infections, increased mortality, and the occurrence of long-term deficits.61

IMPORTANCE OF THE GLOBAL ASSESSMENT IN THE GERIATRIC PATIENT WITH ACUTEINFECTIOUS DISEASES

In elderly patients, acute and chronic conditions lead to impairments of functionality

and, connected with this, to losses of independence. A geriatric assessment may

identify interventions that also have a positive influence on the acute course of disease

by improving functionality. The preventive benefit should also not be underesti-mated.62 Impaired functionality may indicate previously unrecognized diseases63

and is associated with higher mortality.64 Although performance of the geriatric

assessment, in addition to the clinical investigation, does not require special technical

instruments, it calls for a trained investigator to achieve the diagnostic and therapeutic

objectives ( Box 3 ). The use of standardized methods of investigation and assessment

Box 3

Assessment aims

Aims of the geriatric global assessment

Identification of functional deficits

Acute therapy viewed in conjunction with functionality

Adequate preparation for elective treatments

Discharge and send home without/with outpatient aids

Infections in the Elderly 763

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 8/18

( Table 2 ) is another important requirement for successful performance of the geriatric

assessment.

Even if many intensivists do not currently undertake the performance of a specific

geriatric assessment in critically ill, infected geriatric patients, on-going demographic

shifts toward the elderly will likely force consideration of this issue in the near future.65

ASSESSMENT FOR PROGNOSIS

C(U)RB-65 is an easy-to-use tool for severity scores for nonsevere, moderate, and se-

vere pneumonia.66 A score of 2 to 3 points reveals intermediate risk, and a score of 4

defines severe community-acquired pneumonia with a high risk for complications and

mortality ( Table 3 lists more information on pneumonia severity assessment using

CURB-65 and CRB-65). Functional status of the patients is also of importance for

prognostication. Being bedridden, admission from a nursing home or other long-

term care facility, and being dependent in activities of daily living are also poor prog-

nostic markers.8,67

MAJOR INFECTIONS IN THE ELDERLYPneumonia

Fever, sweating, cough, purulent sputum, and dyspnea are typical clinical signs of

pneumonia in young patients,68 in association with new radiographic shadowing for

which is no other explanation.67 As noted, though, many of these signs and symptoms

may be substantially blunted in the elderly. Pneumonia in old age should be consid-

ered a unique entity with significant age-related differences in epidemiology and etiol-

ogy, as well as clinical presentation and management.69

Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia (AsP) arises from misdirection of oropharyngeal secretions with

a high bacterial load or gastric material of very low pH from the stomach into the lower

respiratory tract.70 The risk of AsP shows a strong age association due to a higher inci-

dence of dysphagia in the elderly.71 These infections are generally mixed, frequently

due to anaerobes, S pneumoniae, S aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae, although

gram-negative intestinal bacteria ( Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteria-

ceae), P aeruginosa (in bedridden patients), and group B streptococci.72 AsP tends

to show nonspecific symptoms, such as dyspnea, fever, and general exhaustion, inthe elderly. Radiologically, pulmonary infiltrates are detectable mainly in the posterior

upper lobe segments in the case of aspiration in the lying position, and generally in the

apical lower lobe segments of the right lung in the case of aspiration in the sitting

position.70

Table 2

Standardized geriatric assessments (example selection)

Assessment Evidence

Activities of daily living Coping with everyday life

Timed up and go test Mobility

Minimal mental status test Cognitive performance

Geriatric depression scale Mental well-being

Nutritional risk screening Nutritional status

Barthel index Need for care

Heppner et al764

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 9/18

UTIs

UTIs are a common reason for elderly patients older than 75 years old to be admitted

to the hospital.73 Incontinence, immobility, and chronic bladder catheterization are risk

factors. Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriouria does not generally influence mortal-

ity or morbidity. However, treatment can occasionally result in antibiotic-associated

adverse reactions and the development of resistance.74 As a consequence of age-

related physiologic changes, diagnosis of a true UTI is difficult. Underdiagnosis of UTI occurs with some frequency.75

Antimicrobial therapy is often not concordant with guidelines, given that modifica-

tion of the standard regimen is often needed for geriatric patients. Patient-related diag-

nostic criteria and treatment standards specific to the elderly are recommended.75

Bloodstream Infections

Bacteremia is increasing in frequency in the elderly.76 Nonspecific symptoms are

common at the initial presentation. Bloodstream infections are a major and increasing

cause of morbidity and mortality in the overall and geriatric population, one of the lead-

ing causes of death in the hospital.77 Low albumin rate ( P<.001), high CRP ( P 5 .02),and moderate fever ( P 5 .006) are independent risk factors for mortality in the elderly.

The parameter with the highest risk was a low albumin rate (<30 g/L). Specific recom-

mendations for management of bacteremia in the geriatric patient are required but not

currently in place.78

Fungal Infections

Fungal infections are more frequent and serious in the elderly. Candida albicans still

remains the major pathogen but there is an increase of Candida glabrata (associated

with higher mortality) infection. Patients with swallowing disorder, acid suppression

treatment, or corticosteroid use often show esophageal candidiasis.79 Candiuria is acommon finding in the population of older patients with risk factors (chronic comorbid-

ities, polymedication, or incontinence). C albicans and C glabrata are the usual fungal

pathogens isolated.80 Candida infection of the skin, mucous membranes, or pressure

ulcers is often seen in elderly patients with predisposing factors, particularly dia-

betes.81 Old age is also a risk factor for invasive candidiasis/candidemia and

aspergillosis.82

Table 3

Assessment of the severity of pneumonia in the elderly using the CURB-65 and CRB-65 clinical

prediction rules124

Clinical Sign Score

Confusion 1 pointUrea level >7 m mol/L 1 point

Respiratory rate 30/min 1 point

Blood pressure

Systolic <90 mm Hg 1 point

Diastolic <60 mm Hg 1 point

Age 65 y 1 point

0–1 point5 low risk, ambulatory care; 2 points5 elevated risk hospital admission; 3 points5 highrisk, urgent hospital admission; 4 5 highest risk, r admission to an ICU.

Data from Bauer TT, Ewig S, Marre R, et al. CRB-65 predicts death from community-acquiredpneumonia. J Intern Med 2006;260:93–101.

Infections in the Elderly 765

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 10/18

Sepsis

Sepsis has a high mortality rate in the elderly. It is also the most common cause of

shock83 and among the leading causes of overall mortality globally.84 Case-fatality

rates in older age are increasing.85 For clinicians, mastering the increasing complex

elements of optimal sepsis management for the wide variety of presenting patientsis difficult and new strategies for managing knowledge are necessary. Protocolized

care, whether paper-based or electronic, has been shown to be particularly useful.86

Elderly sepsis patients, in particular, must be treated rapidly to optimize outcome and

protocolized care may be especially beneficial for that reason.87

ANTIMICROBIAL MANAGEMENT

Antibiotics are among the most frequently prescribed drugs. Their widespread use is

primarily responsible for increasing antibiotic resistance, a major problem in older pa-

tients, where infections are more common. Antimicrobial therapy has long been recog-nized as a cornerstone in the treatment of infections.88 Optimal antimicrobial therapy

is crucial for surviving severe infections, sepsis, and septic shock89 and inappropriate

choices can increase morbidity and mortality.90 The central principle of optimizing

antimicrobial therapy is that appropriate antimicrobial therapy has to be initiated as

quickly as possible to save the patient suffering from life-threatening infection.91

Antimicrobial treatment decisions are should be based on a variety of different

factors, including disease severity, clinical picture, and individual patient characteris-

tics. The validity of assumptions on the likely spectrum of underlying pathogens and

their resistance to antibacterials are crucial to initial empiric therapy. As the spectrum

of pathogens not only varies between but also within countries and regions,92

regulardata updates from appropriate surveillance studies covering local or regional charac-

teristics are recommended. Close collaboration between microbiologists, infectious

disease specialists, and local physicians is necessary.93 In elderly patients, assess-

ment of kidney function is especially important because subclinical impairment of

kidney function and chronic kidney failure are prevalent. Failure to implement dose

adjustment can lead to drug-induced acute kidney failure and other serious adverse

effects.94–96

The prevalent microbiology of infection is altered in old age, leading to differences in

optimal empiric antimicrobial coverage for serious infections. For LRTI, S pneumoniae

and S aureus are isolated with increased frequency, whereas a lower incidence of legionella and mycoplasma is found.97–100 Gram-negative bacteria are also more

frequent as causative pathogens in this age group with functional decline.101,102 In

most cases, for serious infections without septic shock, antimicrobial monotherapy

is sufficient. In the presence of severe hypotension and shock, combination therapy

is beneficial.103,104 Early administration of antimicrobials is a key element in the

survival of patients with severe infections.44 In addition, a relationship between antimi-

crobial delay and the increase of organ failure in patients with severe infections has

been shown.105

Several barriers to timely administration of antibiotics can be identified. These bar-

riers include a lack of education, a lack of appreciation of the severity of infection in theelderly, and an increased workload in busy emergency departments106,107 and inten-

sive care units. Atypical presentation, lack of fever, or altered mental status may falsify

the clinical picture and lead to delayed treatment.108 The widespread use of antibac-

terials for infectious diseases has led to an increasing prevalence of resistance of

pathogens, thereby increasing the risk of treatment failure, complications, and death

from infections. Therefore, it is essential to consider current patterns of antimicrobial

Heppner et al766

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 11/18

resistance when making treatment decisions.44,45 Initiation of a microbially inappro-

priate antimicrobial is equivalent to no antimicrobial at all.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics including drug distribution and clear-

ance are clearly independently altered in critically ill and geriatric patients. Changes

in body composition, drug distribution, and elimination kinetics must be carefully

considered in selecting a dosing regime. In addition, adverse effects, such as nausea,

vomiting, or diarrhea (seen with b-lactams, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones109–111 ),

or acute confusional state, somnolence, seizures, hallucinations, or dizziness (fluoro-

quinolones110 ), can be prominent in the elderly, especially in the setting of pre-existing

organ dysfunction. Interactions between antibacterials and other drugs already in use

must also be considered. An overview of adverse effects and potential drug-drug

interactions is seen mostly commonly in the elderly, ill patient, as given in Table 4.

Other Side Effects of Antimicrobial Treatment

Of increasing relevance in the geriatric patient is the appearance of Clostridium diffi-cile–associated diarrhea (CDAD).112–114 CDAD typically occurs during or after a

course of antibiotic treatment in elderly, hospitalized patients with comorbidituies

and ongoing acid suppression therapy. Antibiotic therapy within 6 weeks before

CDAD is a strong risk factor.115 In combination with proton pump inhibitors, the risk

is even higher,116 leading to a 2.5 to 3.5 higher CDAD-related mortality in elderly pa-

tients during severe infections.117,118 Clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, and cephalospo-

rins are associated with the highest risk, although virtually all antibacterials have the

potential to induce CDAD.112–114 There are a wide range of manifestations, from

asymptomatic carriage to fulminant colitis with toxic megacolon. The most common

Table 4

Typical adverse effects and important drug-drug interactions of b-lactams, macrolides, and

fluoroquinolines

Antibacterial Class Typical Adverse Effects Important Drug-Drug Interactions

b-Lactams Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, skinrash, blood count alterations,drug fever

Uricosuric agents: lower b-lactamexcretion

Macrolides Gastrointestinal adverse effects,ototoxicity, ventriculararrhythmias

Antiarrhythmics, QT-prolongingagents: may induce ventriculararrhythmias

CYP3A4-inducing agents (eg,carbamazepine, rifampicin,phenytoin): lower macrolideconcentration

Competition with other drugs forCYP3A4 (eg, statins, digoxin,warfarin): higher competitordrug concentrations

Fluoroquinolones Gastrointestinal adverse effects,

photosensitivity, confusion,delirium, somnolence,hallucinations, dizziness

Antiarrhythmics, QT prolonging

agents: may induce ventriculararrhythmias

Competition by ciprofloxacin withother drugs for CYP1A2 (eg,mirtazapine, warfarin): highercompetitor drug concentrations

Abbreviation: CYP, cytochrome P450.

Infections in the Elderly 767

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 12/18

presentation includes watery diarrhea (rarely blood), abdominal pain and distension,

and fever. For treatment, current antibiotics should be stopped whenever possible

and supportive care initiated. Specific therapy consists of metronidazole in uncompli-

cated infection with vancomycin reserved for severe infection.119 Fidaxomycin, a new

macrocylic oral antibiotic, may be particularly useful in critically ill elderly patients with

a high risk for a relapse.120–122 Relapse within 2 months occurs in about 20% of the

patients with standard therapies.

SUPPORTIVE CARE

To achieve treatment success, supportive care, such as early mobilization, fluid man-

agement with sufficient hydration, and adequate nutrition, is very important in addition

to antimicrobial management. For the elderly patients it is crucial to plan case man-

agement for discharge if necessary with preplanned rehabilitation or geriatric day

clinic stay to strengthen self-dependent life skills. A series of supportive measures

can help prevent infection in the elderly and should be implemented well before prob-lems begin to arise ( Box 4 ). They will also be useful in the convalescence period after

serious infection or critical illness.

OUTCOMES

Infections in old age are more frequent, more severe, and associated with a higher

mortality than they are in young adults, due to multiple different factors. Aging leads

to organ system dysfunction, particularly respiratory, gastrointestinal, and immuno-

logic senescence.69 The management of elderly patients with infections is a challenge.

Factors specific to the elderly should be considered in diagnostic and treatment stra-tegies for this group. The accurate assessment of disease severity is especially impor-

tant in the elderly. The individual characteristics of the patient, such as compliance

issues, the ability to take oral medication, independent activities of daily living, and

the availability of adequate social support, should be considered. In addition, clinical

risk assessment tools (such as the CURB-65 for community-acquired pneumonia)

should be used to help determine whether a patient can safely be treated in the ambu-

latory setting. These tools are also helpful in the selection of the choice of the initial,

empiric antimicrobial. Clinical reassessment should be performed regularly during

the first days of therapy to document clinical stability, to enable timely detection of

treatment failure or possible complications, and also for planning discharge. Treat-ment guidelines of serious infections should be adapted to accommodate the unique

presentation, pathogen profiles, and management challenges of elderly patients.

Box 4

Prophylaxis in old age

Approaches to preventing infections in the elderly:

Preservation of mobility and self-dependence

Preservation of muscle mass and body weight

Sufficient hydration

Personal hygiene

Avoid hospital admissions if possible

Vaccination

Heppner et al768

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 13/18

Demographic shift toward the geriatric age group and the increasing complexity of in-

fectious disease require strong interdisciplinary patient-centered care. Knowledge of

the specific characteristics of serious infections in elderly patients and ongoing

research in this area are required to ensure optimum care of this fragile population.

REFERENCES

1. Gould SJ. Book of the worms. In: Leonardo’s moutain of claims and zhe diet of

worms. New York: Harvard Univ Pr; 1998.

2. Thurston AJ. Of blood, inflammation and gunshot wounds: the history of the con-

trol of sepsis. Aust NZ J Surg 2000;70:855–61.

3. Hurlbert R. Chapter 1: a brief history of microbiology. Microbiology 101/102

internet text [online]. 1999. Available at: http://www.slic2.wsu.edu:82/hurlbert/

micro101/pages/Chap1.html. Accessed December 19, 2012.4. De Costa CM. “The contagiousness of childbed fever”: a short history of puer-

peral sepsis and its treatment. Med J Aust 2002;177:668–71.

5. Baron RM, Baron MJ, Perrella MA. Pathobiology of sepsis: are we still asking the

same questions? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;34:129–34.

6. Francoeur JR. Joseph Lister: surgeon scientist (1827–1912). J Invest Surg 2000;

13:129–32.

7. Sandiumenge A, Diaz E, Bodı M, et al. Therapy of ventilator-associated pneu-

monia. A patient-based approach based on the ten rules of “The Tarragona

Strategy”. Intensive Care Med 2003;29(6):876–83.

8. Ehrlich P. The Therapia sterilisans magna. Lancet 1913;16:445–51.9. Marrie TJ, Haldane EV, Faulkner RS, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia

requiring hospitalization. Is it different in the elderly? J Am Geriatr Soc 1985;

33:671–80.

10. Osler W. Principles and practice of medicine designed for the use of practi-

tioners and students of medicine. 3rd edition. London: Young J. Pentland;

2004. p. 108.

11. Lang E, Gassmann KG. Pro Aging statt Anti-Aging-was ist da anders? Euro J

Ger 2005;7:190–3.

12. Castle SC. Impact of age-related immune dysfunction on risk of infections.

Z Gerontol Geriatr 2000;33:341–9.13. Rozzini R, Sabatini T, Trabutchi M. Assessment of pneumonia in Elderly patients.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:308–17.

14. Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-

associated Pneumonia: results from a large US database of culture-positive

pneumonia. Chest 2005;128:3854–62.

15. El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, et al. Microbiology of severe aspiration pneu-

monia in institutionalized elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1650–4.

16. Tockman MS. Aging of the respiratory system. In: Hazzard WR, Andres R,

Bierman EL, et al, editors. Principles of geriatric medicine and gerontology.

New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. p. 499–508.17. French DD, Cambell RR, Rubenstein LZ. Long-stay nursing home residents’

hospitalizations in the VHA: the potential impact of aligning financial incentives

on hospitalizations. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:499–503.

18. Vergidis P, Hamer DH, Meydani SN, et al. Patterns of antimicrobal use for respi-

ratory tract infections in older residents of long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr

Soc 2011;59:1093–8.

Infections in the Elderly 769

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 14/18

19. Alvarez-Rodrıgez L, Lopez-Hoyos M, Munoz-Cacho P. Aging is associated with

circulation cytocine dysregulation. Cell Immunol 2012;273:124–32.

20. Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Wick G. The aging of the immune system. Adv Immu-

nol 2002;80:243–84.

21. Butcher SK, Chahal A, Nayak L, et al. Senescence in innate immune responses:

reduced neutrophil phagocytic capacity and CD16 expression in elderly hu-

mans. J Leukoc Biol 2001;70:881–6.

22. Aspinall R, Del Giudice D, Effros RB, et al. Challenges for vaccination in the

elderly. Immun Ageing 2007;11:4–9.

23. Carbon C. Optimal treatment strategies forcommunity-acquired pneumonia: high-

risk patients (geriatric and with comorbidity). Chemotherapy 2001;47(Suppl 4):

19–25.

24. Marrie TJ. Pneumonia in the elderly. Curr Opin Pulm Med 1996;2(3):192–7.

25. Sieber C. Frailty. Ther Umsch 2008;65:421–6.

26. Fried L, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence of a pheno-

type. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–56.

27. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus

on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcope-

nia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010;39(4):412–23.

28. Barbieri M, Ferucci L, Rango E, et al. Chronic inflammation and the effect of IGF-1

on muscle strength and power in older persons. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab

2003;284:E481–7.

29. Leng S, Chaves P, Koenig K, et al. Serum interleukin-6 and haemoglobin as

physiological correlates in the geriatric syndrome of frailty: a pilot study. J Am

Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1268–71.30. Heppner HJ, Bauer JM, Sieber CC, et al. Laboratory aspects relating to the

detection and prevention of frailty. Int J Prev Med 2010;1:149–57.

31. Erschler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expres-

sion, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annu Rev Med 2000;51:245–70.

32. Bruunsgaard H, Ladelund S, Pedersen AN, et al. Predicting death from tumor

necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in 80-year-old people. Clin Exp Immunol

2003;132:24–31.

33. Dumke BR, Lees SJ. Age-related impairment of T-cell induced sceletal muscle

precursor cell function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011;300:C1226–33.

34. von Haeling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of sarcopenia: facts andnumbers of prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle

2010;1:129–33.

35. Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. Clin Geriatr Med

2011;27(3):337–9.

36. Landi F, Liperoti R, Fusco D, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality among older

nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:121–6.

37. Struchler HP. Abklarung und Antibiotikatherapie von Infektionen in der Hausarzt-

praxis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000;130:1437–46.

38. Waalen J. Is older colder or colder older? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:

487–92.39. Blatteis CM. Age-dependent changes in temperature regulation – a mini review.

Gerontology 2012;58:289–95.

40. Mikkelsen ME, Gaieski DF. Antibiotics in sepsis: timing, appropriateness, and (of

course) timely recognition of appropriateness. Crit Care Med 2011;39:2184–6.

41. Yoshikawa TT, Norman DC. Fever and infection in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr

Soc 2000;44:74–82.

Heppner et al770

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 15/18

42. Christ M, Heppner HJ. Der COPD Patient mit Atemnot. Ther Umsch 2009;66:

657–64.

43. Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al. BTS guidelines for the management

of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax 2009;

64(Suppl 3):iii1–55.

44. Hoffken G, Lorenz J, Kern W, et al. S3-guideline on ambulant acquired pneu-

monia and deep airway infections. Pneumologie 2009;63:e1–68.

45. Sorde R, Falco V, Lowak M, et al. Current and potential usefulness of pneumo-

coccal urinary antigen detection in hospitalized patients with community-

acquired pneumonia to guide antimicrobial therapy. Arch Intern Med 2011;

171(2):166–72.

46. Solh El AA, Aquilina AT, Gunen H, et al. Radiographic resolution of community-

acquired bacterial pneumonia in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(2):

224–9.

47. Delerme S, Ray P. Acute respiratory failure in the elderly: diagnosis and prog-

nosis. Age Ageing 2008;37:251–7.

48. Lippi G, Meschi T, Cervellin G. Inflammatory biomarker fort the diagnosis, moni-

toring and follow-up of the community-acquired pneumonia: clinical evidence

and perspectives. Eur J Intern Med 2011;22(5):460–5.

49. Gilbert DN. Procalcitonin as a biomarker in respiratory tract infection. Clin Infect

Dis 2011;52:S346–50.

50. Kruger S, Ewig S, Marre R, et al. Procalcitonin predicts patients at low risk of

death from community-acquired pneumonia across all CRB-65 classes. Eur Re-

spir J 2008;31:349–55.

51. Heppner HJ, Bertsch T, Alber B. Procalcitonin: inflammatory biomarker for as-sessing the severity of community-acquired pneumonia-a clinical observation

in geriatric patients. Gerontology 2010;56(4):385–9.

52. Muller F, Christ-Crain M, Bregenzer T, et al. Procalcitonin levels predict bacter-

emia in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective cohort trial.

Chest 2010;138(1):121–9.

53. Inouye SK. The dilemma of delirium: clinical and research controversies

regarding diagnosis and evaluation of delirium in hospitalized elderly medical

patients. Am J Med 1994;97:278–88.

54. Lipowski ZJ. Update on delirium. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992;15:335–46.

55. Weinrich S, Sarna L. Delirium in the older person with cancer. Cancer 1994;74:2079–91.

56. OKeeffe ST. Clinical subtypes of delirium in the elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn

Disord 1999;10:380–5.

57. S3-Leitlinie CAP, 2009’er update: AWMF online. Available at: www.awmf.org/

uplouds/tx. Accessed December 20, 2012.

58. Eriksson I, Gustafson Y, Fagerstrom L, et al. Urinary tract infection in

very old women is associated with delirium. Int Psychogeriatr 2011;23(3):

496–502.

59. Han JH, Wilson A, Ely EW. Delerium in the older emergency department patient:

a quiet epidemic. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2010;28(3):611–31.60. Singler K, Singler B, Heppner HJ. Akute Verwirrtheit im Alter. Dtsch Med

Wochenschr 2011;136:681–4.

61. Quinn TJ, McArthur K, Ellis G, et al. Functional assessment in older people. BMJ

2011;343:d4681–8.

62. Schuhmacher JG. Emergency medicine and older adults: continuing challenges

and opportunities. Am J Emerg Med 2005;23:556–60.

Infections in the Elderly 771

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 16/18

63. Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R, et al. Objectively measured physical capability

levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:

c4467.

64. Stott DJ, Langhorne P, Knight PV. Multidisciplinary care for elderly people in the

community. Lancet 2008;371:699–700.

65. Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneu-

monia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and valida-

tion study. Thorax 2003;58:377–82.

66. Community Acquired Pneumonia in Adults Guideline Group. BTS guidelines for

the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009.

Thorax 2009;64(Suppl III):1–55.

67. Fine MJ, Orloff JJ, Arsiumi D, et al. Prognosis of patients hospitalized with

community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 1990;88(5N):1N–8N.

68. Malin A. Pneumonia in old age. Chron Respir Dis 2011;8:207–10.

69. Ott SR, Lode H. Diagnostik und Therapie der Aspirations pneumonie. Dtsch

Med Wochenschr 2006;131:624–8.

70. Loeb M. Community acquired pneumonia. Clin Evid 2003;10:1724–37.

71. Trivalle C, Martin E, Martel P, et al. Group B streptococcal bacteraemia in the

elderly. J Med Microbiol 1998;47:649–52.

72. George J, Sturegess I, Purewal S, et al. Improving quality and value in health

care for frail older people. Qual Ageing 2007;8:4–9.

73. Abrutyn E, Mossey J, Berlin JA, et al. Does asymptomatic bacteriuria predict

mortality and does antimicrobial treatment reduce mortality in elderly ambula-

tory women? Ann Intern Med 1994;120:827–33.

74. Woodford HJ, George J. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infectionsin hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:107–14.

75. Richardson JP. Bacteremia in the elderly. J Gen Intern Med 1993;8:89–92.

76. National nosocomial infections surveillance (NNIS) system report, data sum-

mary from January 1992-April 2000, issued June 2000. Am J Infect Control

2000;28(6):429–48.

77. Burlaud A, Mathieu D, Falissard B, et al. Mortality and bloodstream infections in

geriatrics units. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010;51(3):e106–9.

78. Weerusuriya N, Snape J. Oesophageal candidiasis in elderly patients: risk fac-

tors, prevention and management. Drugs Aging 2008;25:119–30.

79. Fraisse T, Cruzet J, Lachaud L, et al. Candiduria in those over 85 years old: aretrospective study of 73 patients. Intern Med 2011;50:1935–40.

80. Martin ES, Elewski BE. Cutaneous fungal infections in the elderly. Clin Geriatr

Med 2002;18:59–75.

81. Lamagni TL, Evans BG, Shigematsu M, et al. Emerging trends in the epidemi-

ology of invasive mycoses in England and Wales (1990–9). Epidemiol Infect

2001;126:397–414.

82. El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Alsawalha LN, et al. Outcome of septic shock in older

adults after implementation of the sepsis “bundle”. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:

272–8.

83. Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the UnitedStates from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1546–54.

84. Martin GS, Mannino DM, Moss M. The effect of age on the development and

outcome of adult sepsis. Crit Care Med 2006;34:15–21.

85. Kollef MH, Micek ST. Using protocols to improve patient outcomes in the inten-

sive care unit: focus on mechanical ventilation and sepsis. Semin Respir Crit

Care Med 2010;31:19–30.

Heppner et al772

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 17/18

86. Heppner HJ, Singler K, Kwetkat A, et al. Do clinical guidelines improve manage-

ment of sepsis in critically ill elderly patients? A before-and-after study of the im-

plementation of a sepsis protocol. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2012;124:692–8.

87. Bochud PY, Glauser MP, Calandra T. Antibiotics in sepsis. Intensive Care Med

2001;27:S33–48.

88. Abad CL, Kumar A, Safdar N. Antimicrobial therapy of sepsis and septic shock-

when are two drugs better than one? Crit Care Clin 2011;27:e1–27.

89. Pinder M, Bellomo R, Lipman J. Pharmacological principles of antibiotic pre-

scription in the critically ill. Anaesth Intensive Care 2002;30(2):134–44.

90. Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of

effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human

septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1589–96.

91. Green DL. Selection of an empiric antibiotic regimen for hospital-acquired pneu-

monia using a unit and culture type specific antibiogram. J Intensive Care Med

2005;20:296–301.

92. Thiem U, Heppner HJ, Pientka L. Elderly patients with community-acquired

pneumonia: optimal treatment strategies. Drugs Aging 2011;28:519–37.

93. Dong K, Quan DJ. Appropriately assessing renal function for drug dosing.

Nephrol Nurs J 2010;37(3):304–8.

94. Murphree DD, Thelen SM. Chronic kidney disease in primary care. J Am Board

Fam Med 2010;23(4):542–50.

95. Olyaei AJ, Bennett WM. Drug dosing in the elderly patients with chronic kidney

disease. Clin Geriatr Med 2009;25(3):459–527.

96. Venkatesan P, Gladman J, Macfarlane JT, et al. A hospital study of community

acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Thorax 1990;45:254–8.97. Fernandez-Sabe N, Carratala J, Roson B, et al. Community-acquired pneu-

monia in very elderly patients: causative organisms, clinical characteristics,

and outcomes. Medicine 2003;82:159–69.

98. Martin CM, Kunin CM, Gottlieb LS, et al. Asian influenza A in Boston, 1957-1958.

II. Severe staphylococcal pneumonia complicating influenza. Arch Intern Med

1959;103:532–42.

99. Niederman MS, Ahmed QA. Community-acquired pneumonia in elderly pa-

tients. Clin Geriatr Med 2003;19(1):101–20.

100. File TM. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2003;362(9400):1991–2001.

101. Welte T, Kohnlein T. Global and local epidemiology of community-acquiredpneumonia: the experience of the CAPNETZ Network. Semin Respir Crit Care

Med 2009;30(2):127–35.

102. Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Light B, et al. Early combination antibiotic therapy

yields improved survival compared with monotherapy in septic shock: a

propensity-matched analysis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1773–85.

103. Kumar A, Safdar N, Kethireddy S, et al. A survival benefit of combination antibi-

otic therapy for serious infections associated with sepsis and septic shock is

contingent only on the risk of death: a meta-analytic/meta-regression study.

Crit Care Med 2010;38:1651–64.

104. Garnacho-Montero J, Aldabo-Pallas T, Garnacho-Montero C, et al. Timingof adequate antibiotic therapy is a greater determinant of outcome than

are TNF and IL-10 polymorphisms in patients with sepsis. Crit Care

2006;10:R111.

105. Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, et al. The impact of emergency department

crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired

pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med 2007;50:510–6.

Infections in the Elderly 773

8/12/2019 Critical Care Clinics 2013 29 (3) 757

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/critical-care-clinics-2013-29-3-757 18/18

106. Pines JM, Morton MJ, Datner EM, et al. Systematic delays in antibiotic adminis-

tration in the emergency department for adult patients admitted with pneu-

monia. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:939–45.

107. Waterer GW, Kessler LA, Wunderink RG. Delayed administration of antibiotics

and atypical presentation in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 2006;130:

11–5.

108. Herring AR, Williamson JC. Principles of antimicrobial use in older adults. Clin

Geriatr Med 2007;23(3):481–97.

109. Zenilman J. Infection and Immunity. In: Durso SC, editor. Oxford American

Handbook of Geriatric Medicine. Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 642.

110. Stahlmann R, Lode H. Safety considerations of fluoroquinolones in the elderly:

an update. Drugs Aging 2010;27(3):193–209.

111. Weber S, Mawdsley E, Kaye D. Antibacterial agents in the elderly. Infect Dis Clin

North Am 2009;23(4):881–98, viii.

112. Heinlen L, Ballard JD. Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Med Sci 2010;340(3):

247–52.

113. Shah D, Dang MD, Hasbun R, et al. Clostridium difficile infection: update on

emerging antibiotic treatment options and antibiotic resistance. Expert Rev

Anti Infect Ther 2010;8(5):555–64.

114. Simor AE. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infec-

tion in long-term care facilities: a review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(8):1556–64.

115. Vesteinsdottir I, Gudlaugsdottir S, Einarsdottir R, et al. Risk factors for Clos-

tridium difficile toxin-positive diarrhea: a population-based prospective case–

control study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;31:2601–10.

116. Cunningham R, Dial S. Is over-use of proton pump inhibitors fuelling the currentepidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea? J Hosp Infect 2008;70:

1–6.

117. Miller M, Gravel D, Mulvey M, et al. Health care-associated Clostridium difficile

infection in Canada: patient age and infecting strain type are highly predictive of

severe outcome and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:194.

118. Wenisch JM, Schmid D, Tucek G, et al. A prospective cohort study on hospital

mortality due clostridium difficile infection. Infection 2012;40:479–84.

119. Bauer MP, Kujiper EJ, Van Dissel JT, et al. European Society of Microbiology and

Infectious Diseases (ESCMID): treatment guidance document for clostridium

difficile infection (CDI). Clin Microbiol Infect 2009;15:1067–79.120. Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for clos-

tridium difficile infections. N Engl J Med 2011;364:422–31.

121. Louie TJ, Cannon K, Byrne B, et al. Fidaxomicin preserves the instestinal micro-

biome during and after treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and re-

duces both toxin reexpression and recurrence of CDI. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:

S132–42.

122. Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infec-

tion with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-

inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:281–9.

123. Thiesemann R: Feststellung des Praventions- und Rehabilitationsbedarfeshochbetagter Pflegebedurftiger als gutachterliche Aufgabe, Schwerpunktsemi-

nar fur Medizinische Gutachter des PKV-Verbandes, Berlin 2009; Ubersetzung

nach: Beschluss der United European Medical Societies – Geriatric Medicine

Section (UEMS-GMS) am 3. Mai 2008 auf Malta.

124. Bauer TT, Ewig S, Marre R, et al. CRB-65 predicts death from community-ac-

quired pneumonia. J Intern Med 2006;260:93–101.

Heppner et al774

Related Documents