Natural Areas Journal . . . to advance the preservation of natural diversity A publication of the Natural Areas Association - www.naturalarea.org © Natural Areas Association Natural Areas Journal 31:156 Controlling an Invasive Shrub, Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii DC), Using Directed Heating with Propane Torches Jeffrey Ward 1,2 1 Department of Forestry and Horticulture The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street New Haven, CT 06511 Scott Williams 1 2 Corresponding author: [email protected]; 203-974-8495

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Natural Areas Journal. . . to advance the preservation of natural diversity

A publication of the Natural Areas Association - www.naturalarea.org

© Natural Areas Association

Natural Areas Journal 31:156

Controlling an Invasive Shrub,

Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii DC), Using Directed

Heating with Propane Torches

Jeffrey Ward1,2

1DepartmentofForestryandHorticultureTheConnecticutAgricultural

ExperimentStation123HuntingtonStreetNewHaven,CT06511

Scott Williams1

2Correspondingauthor:[email protected];203-974-8495

156 Natural Areas Journal Volume 31 (2), 2011

Natural Areas Journal 31:156

•

Controlling an Invasive Shrub,

Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii DC), Using Directed

Heating with Propane Torches

Jeffrey Ward1,2

1DepartmentofForestryandHorticultureTheConnecticutAgricultural

ExperimentStation123HuntingtonStreetNewHaven,CT06511

Scott Williams1

•

R E S E A R C H N O T E

2Correspondingauthor:[email protected];203-974-8495

ABSTRACT: Japanesebarberry (Berberis thunbergiiDC) isanon-nativeshrubcurrently found in31statesandfourCanadianprovinces.Weexaminedtheeffectivenessofdirectedheatingusing400,000BTUbackpackpropanetorchestocontrolJapanesebarberryinfestationsattwostudyareasinsouthernConnecticut.Each study areahad eight 50-mx50-mplots.Treatment combinations included apre-leafoutorpost-leafoutinitialtreatmentwithpropanetorchestoreducethesizeofestablishedclumpsand an early (late June), mid (early July), or late (late July) follow-up treatment to kill sprouts thatdevelopedfromsurvivingrootcrowns.Alltreatmentcombinationswereequallyeffectiveandreducedbarberry abundance (a surrogate for cover) from31%prior to treatment to only0.5% the followingautumn(i.e.,a98%reduction).Alltreatmentcombinationswerealsoequallyeffectiveinreducingthesizeof survivingbarberry to an averageofonly11 cmcomparedwith74 cm foruntreated clumps.Estimatedlaborcostsusingpropanetorchesforbothinitialandfollow-uptreatmentwas2.5hr/haforevery1%pretreatmentabundance(e.g.,25hrfora1-hastandwith10%abundance).Becausetimingofinitialtreatments(pre-leafoutvs.post-leafout)andfollow-uptreatment(early,mid,late)wereequallyeffective in reducing Japanese barberry abundance and height of surviving stems, initial treatmentscanbecompletedfromMarch-Juneandfollow-uptreatmentscanbecompletedfromJune-August insouthernNewEngland.Forhabitatrestorationprojectsonpropertieswhereherbicideuseisrestricted,directedheatingwithpropanetorchesprovidesanon-chemicalalternativethatcaneffectivelycontrolinvasiveJapanesebarberry.

Index terms:invasiveshrub,mortality,non-chemicalcontrol,propanetorch

INTRODUCTION

An increasingly common challenge fornaturalresourcesmanagersiscontrollinginfestationsof invasive shrubs innaturalandmanagedlandscapes(Ehrenfeld1997;Tempel et al. 2004;Webster et al. 2006;Gubanyi et al. 2008; Honu et al. 2009).Densethicketsofinvasiveshrubshavede-velopedthroughoutthedeciduousforestintheeasternUnitedStates,especiallywherewhite-taileddeer(Odocoileus virginianusZimmermann)populations are high (Eh-renfeld1997;SilanderandKlepeis1999).OnespeciesofconcernisJapanesebarberry(Berberis thunbergii DC),nowclassifiedasinvasivein20statesandfourCanadianprovinces.Itisalsoestablishedinatleastanother 11 states (USDA, NRCS 2010).Throughoutthispaper,Berberis thunbergii willbereferredastoJapanesebarberryorjustbarberry.

Non-native shrubs, including Japanesebarberry, can form dense thickets thatinhibit forest regeneration and nativeherbaceousplantpopulations(Kourtevetal.1998;CollierandVankat2002;Millerand Gorchov 2004). Barberry can altersoilbiotaandfunctionbyincreasingsoilnitrificationandpH(Kourtevetal.1999;Ehrenfeldetal.2001).Inaddition,earth-wormdensitiesaregreaterandleaflitterisreducedinbarberryinfestations(Kourtev

etal.1999).Lossof leaf littercancauseincreased soil erosion and sedimentationloads into adjacent streams as well as alossofsomeherbaceousspecies(Haleetal.2008).Barberryalsohasanindirect,ad-verseimpactonhumanhealthbyfunction-ingasdiseasefociwithenhancedlevelsofblackleggedticks(Ixodes scapularisSay)infected with the Lyme disease-causingspirochete,Borrelia burgdorferi(Johnson,Schmidt,Hyde,Steigerwaldt&Brenner)(Williamsetal.2009).

Eradicationorcontrolofinvasivespeciesisoftenthecrucialfirststepinrestorationofnaturalareas(D’AntonioandMeyerson2002). However, invasive control can beespeciallyproblematiconpropertieswhereherbicideuse is restrictedby regulations(e.g.,parks,drinkingwatersupplywater-sheds),deeds,oractivepublicopposition.BiocontrolshaveshownpromiseforsomeinvasivespeciessuchasAilanthus altissima((Mill.)Swingle)(SchallandDavis2009),Lythrum salicaria (L.) (Wilson et al.2004),andothers(Hough-Goldsteinetal.2009).However,formostwoodyspecies,includingbarberry,non-chemicalcontrolis largely limited to root wrenching, re-peated clipping (mowing), or prescribedfire.Rootwrenchingislaborextensiveandexposesmineralsoilthatcanbecolonizedagainbyinvasivespecies(D’AntonioandMeyerson 2002). Repeated clipping ormowingmaybeeffectiveforspeciesthat

Volume 31 (2), 2011 Natural Areas Journal 157

donotsprout;butlesssoforshade-tolerantspeciesthatsprout(LukenandMattimiro1991).Prescribedfirecanbeeffectiveforcontrollingbarberry(Richburg2005;Wardetal.2009),butisnotanoptiononmanyproperties.

A non-chemical treatment for smallerinfestations(<10ha) isdirectedheatingusingportablepropane torches.Directedheating with torches was reported effec-tiveforcontrollingavarietyofhardwoodspeciesinNewHampshire(CavanaghandWeyrick1978),Cornishheath(Erica va-gansL.)inSpain(ObesoandVera1996),andbellyachebush(Jatropha gossypiifoliaL.)inAustralia(VitelliandMadigan2004).Becausebarberryspreadsbylayering(inwhich an aerial stem can form adventi-tious roots and eventually become anindependent plant) in forests with intactcanopies (Ehrenfeld 1999; DeGasperisandMotzkin2007)andhaslowseedlingrecruitmentbecauseofthelackofaseedbank(D’Appollonio1997),eradicationofestablishedplantsshouldleadtoexcellentlong-termcontrol.

OurearlierworkfoundthatpropanetorchescanprovidecontrolofbarberryforatleasttwoyearsonsmallscaleplotsinConnecti-cut(Wardetal.2010).Theobjectiveofthisstudywastoexaminethepracticalityandeffectiveness of using backpack propanetorchestocontrolbarberryatscales(2ha)typicalofsmallerinfestations,using0.25ha treatment plots. While earlier studies(Ward et al. 2009, 2010) examined theresponse of individual barberry clumpsto treatment, this study examined howtreatmentsreducedbarberryabundance.Ifweassumethatbarberryabundanceisanadequatesurrogateforallocationoflimitedresourcesonasite(e.g.,light,nutrients),then reducing barberry should allow fortheuseofreleasedresourcestowardsthere-establishmentandspreadofnativetreeseedlingsandherbaceousplants.

METHODS

Study Areas

In 2008, two 2-ha study areas were es-tablishedinsouthernConnecticut:onein

NorthBranford,Conn.,onSouthCentralConnecticut Regional Water Authorityproperty (Tommy Top) and one in Red-ding,Conn.,onCentennialWatershedStateForest(Greenbush)cooperativelymanagedbyAquarionWaterCompany,TheNatureConservancy,andConnecticutDepartmentofEnvironmentalProtection.

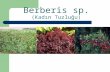

Dominant forest trees were primarilysugar maple (Acer saccharum Marsh.)withmixedoak(Quercusspp.)atTommyTop,andredmaple(Acer rubrumL.),ash(Fraxinus spp.), and oak at Greenbush.Both study areas had extensive areas ofbarberry that were excluding desirableforestregenerationandnativeherbaceousvegetation (Figure 1). Study areas wereagriculturalfieldsor pastures abandonedin the early 1900s. Management wasnegligibleatbothplotsexceptforsalvageharvest of someeasternhemlock (Tsuga canadensis(L.)Carriere)intheearly1990satTommyTop.

Design and measurements - barberry

Each study area was divided into eight50-m x 50-m (0.25 ha) plots, randomlyassignedtooneofeighttreatments:con-trol, a single treatment (mid-July); or 2

treatments, the first applied pre-leafout(March) or post-leafout (April) and thesecondappliedearlysummer(lateJune),mid-summer(earlyJuly),orlatesummer(lateJuly).Treatmentconsistedofdirectedheatingwith400,000-BTUpropanetorches(BP2512SVC,FlameEngineering Inc.,LaCrosse, Kan.). Initial treatments wereapplied to reduce the size of establishedbarberryclumps,andfollow-uptreatmentskilledsproutsthatdevelopedfromsurviv-ingrootcrowns.

Withineachplotateachstudyarea,twenty-fivesamplepointswereestablishedona5-mx5-mgridwith8mspacingbetweenpoints. Sample points were permanentlylocatedwithawireflagandwereatleast9mfromplotedges.Barberryheightandabundancewereestimatedateachsamplepoint.For this study,abundancewasde-finedastheproportionofsixteen17.7-cmx17.7-cmcellswithina0.5m2samplingframe,centeredontheflaggedpoint,thathadatleastonelivebarberrystemorleaf(Figure2).Forexample, ifbarberrywasobservedinfivecells,thenabundancewas5/16 = 31%. This method, while biasedto give slightly higher estimates thantraditionalcoverestimates,especiallyforlow density patches, is reproducible andcan be used in both dormant (leaf-off)

Figure1-Dense,unmanagedJapanesebarberrystandinRedding,Conn.

158 Natural Areas Journal Volume 31 (2), 2011

andgrowingseasons.Occasionally,smallstemsburiedunderseveralinchesofsnowwere missed during the dormant seasonfield measurements. This resulted in aslightunderestimationofabundancewhensampledinthedormantseasonrelativetogrowingseasonestimations.

Forthisstudy,frequencywasthepropor-tionofflaggedpoints(notcells)thathadat least one live barberry stem or leaf.At each point, average barberry heightwas concurrently estimated in 30-cmincrements.MeasurementsweremadeinMarch (pre-treatment), late Juneprior tothefollow-uptreatments(2ndphase),andagaininOctober.

Werecordedfuelconsumptionbyweighingpropanetankstothenearest0.05kgbeforeandaftertreatingeachplot.Totaltreatmenttime and number of crew members wasrecordedforeachplot.

Flamefromthepropane torcheswasap-plied to thebaseof a clump, at the root

crown/soilinterface,andacrossthetopofthe root crown where individual ramets(stems)emerged.Treatmentcontinueduntilthe individual ramets and the top of therootcrownbecamecarbonizedandbeganto glow. This treatment simultaneouslydestroyedthecambialtissueoftheramets,effectivelygirdlingthem,andmanyofthedormantbuds.Onlyleaflitterwithinsev-eralcentimetersoftreatmentclumpswasincidentallyburned.Treatmenttimesvariedfrom10secondsfor thesmallestclumpsto40 seconds for the largest clumps.Toreduce the risk of wildfire, all directedflametreatmentswerecompletedondayswhen the leaves were damp or wet andincludedsomedaysof light tomoderaterainshowers.

Statistical analysis

Atwo-factor(studyarea,initialtreatment)analysisofvariance (ANOVA)withpre-treatment abundance as a covariate wasused to compare the influence of initialtreatmentsonabundanceinJune2008.All

abundancevalueswerearcsinetransformedtostabilizethevariance(NeterandWas-serman1974).Tukey’sHSDtestwasusedto test for significant differences amonginitialtreatments.Differenceswerejudgedsignificantatp<0.05.

Timing (pre-leafout vs. post-leafout) ofinitialtreatmentdidnothaveasignificanteffect on abundance values through lateJune(seeResults).Therefore,initialtreat-mentwasnot includedasa factor in theanalysisof follow-up treatments.A two-factor (study area, follow-up treatment)ANOVAwithpretreatmentabundanceasacovariatewasusedtocomparetheinflu-enceoffollow-uptreatmentsonabundancein October.Again, all abundance valueswerearcsine transformed tostabilize thevariance. Tukey’s HSD test was used totestforsignificantdifferencesamongini-tial treatments. Differences were judgedsignificantatp<0.05.

Labor hours and fuel consumed weretrackedforallinitialandfollow-uptreat-ments. A two-factor (study area, initialtreatment) ANOVA with pretreatmentabundance as a covariate was used tocompareinitialtreatmentcosts.Costwasdefinedasthenumberofhoursperhectaretocompletetreatments.Tukey’sHSDtestwasusedtotestforsignificantdifferencesamonginitialtreatments.Differenceswerejudgedsignificantatp<0.05.Becausecostsdidnotvaryamonginitialtreatments,initialtreatmentcostwasnotincludedasafactorintheanalysisoffollow-uptreatmentcosts.Atwo-factor(studyarea,initialtreatment)ANOVAwithpretreatmentabundanceasacovariatewasusedtocomparefollow-uptreatmentcosts.

RESULTS

Priortotreatment,barberryabundanceav-eraged31%acrossallplots,rangingfrom10%-55%.Pre-treatmentabundancedidnotdiffer among study areas (F=0.93, df=1,p=0.360),initialtreatmentplots(F=0.080,df=2, p=0.924), or follow-up treatmentplots(F=0.253,df=3,p=0.857).Directedheating significantly reduced barberryabundancetoameanof6.3%(onetreat-ment)or0.7%(twotreatments)(Figure3).

Figure 2 - Sampling frame used to estimate Japanese barberry abundance.Abundance was definedas theproportionof sixteencells thathadbarberry, i.e., three cellswithbarberrywouldprovideanestimatedabundanceof3/16=19%.

Volume 31 (2), 2011 Natural Areas Journal 159

Timingofinitialtreatments(pre-leafoutvs.post-leafout)hadnoeffectonabundanceestimatesinJune(F=2.262,df=1,p=0.163)or in October (F=0.093, df=1, p=0.769).Similarly,timingoffollow-uptreatmentshadnoeffectonfinalabundanceestimatesinOctober(F=1.663,df=2,p=0.262).Thefollow-up treatment resulted in barberryabundanceof0.5%comparedwith3.9%onplotswithonlyonetreatment.

The number of directed heat treatmentsusingpropane torchesdidhaveaneffectonbarberryabundanceinOctober(F=83.5,df=2,p<0.01).Onetreatmentwithpropanetorchesreducedbarberryabundancebyanaverageof83%andtwotreatmentsreducedbarberryabundancebyanaverageof98%.Frequency,theproportionofsamplepointsthat had at least one barberry, averaged52%priortoinitial treatment(Figure4).Directed heating using propane torcheswashighlyeffectiveinreducingbarberryfrequency. Initial treatments both beforeand after leafout were equally effectivein reducing barberry frequencies. Bar-berryfrequencyinOctoberdifferedbythenumberofdirectedheattreatmentsusingpropane torches (F=24.2, df=2, p<0.01).WhiletheOctobersurveyfoundover60%of points on untreated plots had at least

one barberry, a single treatment reducedfrequencyto18%.Twotreatmentsreducedfrequencytoonly5%.

Averageheightofbarberrywas78+4cminMarchpriortotreatmentand74+4cmin

untreatedplotsinOctober.Directedheatingusingpropanetorcheswashighlyeffectiveinreducingtheheightofbarberry(Figure5). Barberry heights in October differedby number of directed heat treatments(F=16.4, df=2, p<0.01)–27+4 and 11+5cm for once and twice treated barberry,respectively,comparedwith74+4cmforuntreated barberry.Therefore, relative tountreatedclumpsinOctober,onedirectedheattreatmentreducedtheaveragesizeofbarberry clumps by 64% and two treat-mentsreducedtheaveragesizeby85%.

Labor costs (hours/ha) for both initialandfollow-uptreatmentswerecorrelatedwith pretreatment barberry abundancevalues, r2=0.67andr2=0.60, respectively(Figure6).Fortheinitialtreatmentsusedtoreducethesizeofestablishedbarberryclumps,laborcostsdidnotdifferbetweenthepre-leafoutandpost-leafoutperiods(F=0.006,df=1,p=0.942).Similarly,laborcostsdidnotdifferbetweentheearly,mid,and late summer treatment periods forthefollow-uptreatmentsusedtokillnewsproutsthatdevelopedfromsurvivingrootcrowns,(F=0.74,df=2,p=0.510).

Laborcostsforevery1%barberryabun-dancewereestimatedas1.5hr/haforinitial

Figure3 -Estimatedbarberryabundancebefore treatmentsand in followingOctoberbynumberofpropanetreatments:None(n=2),Once(n=2)andTwice(n=12).Abundancewasanestimateofthepro-portionofareacoveredwithbarberry.ValueswithsamelettersabovebarswerenotfoundsignificantlydifferentusingTukey’sHSDtestatP<0.05.

Figure4-Estimatedbarberryfrequency(SE)beforetreatmentsandinfollowingOctoberbynumberofpropanetreatments.Frequencyistheproportionofsamplepointsthathadatleastonebarberrystem.ValueswithsamelettersabovebarswerenotfoundsignificantlydifferentusingTukey’sHSDtestatP<0.05.Note:OnceandTwicetreatedwerenotsignificantlydifferentatP=0.055.

160 Natural Areas Journal Volume 31 (2), 2011

treatment and 1.0 hrs/ha for follow-uptreatments. Thus, estimated labor costsusingpropanetorchesforbothinitialandfollow-up treatment would be 2.5 hr/haforevery1%abundance(e.g.,25hrfora1-hastandwith10%barberryabundance).Itshouldbenotedthattheseestimatesdonotincludetimerequiredfortravel,refuel-ing,andbreaks.

Theamountofpropaneusedforthedirect-edheatingtreatmentswashighlycorrelated(r2=0.88)withtheamountoftimeneededtotreatbarberryinfestations.Whiletherewasastatisticaldifferencebetweeninitialand follow-up treatments in the amountofpropaneusedperhour(F=6.133,df=1,p=0.021),theactualdifference,0.28kg/hrwas of little practical difference relativetothe2.49kg/hraverageforbothperiodscombined. Using the example above, a1-ha stand with estimated 10% barberryabundancewouldrequireatotalof62kgofpropaneforboththeinitialandfollow-uptreatments.

DISCUSSION

Atwo-stepprocessofdirectedheatingus-ingpropanetorchescancontrolbarberryinfestations. By every metric examined(abundance,frequency,height)inthecur-

rentstudy,directedheatingwithpropanetorches was effective in reducing theamountofbarberryinforestunderstories(Figures3-5).Anearlierreportfoundthattwo directed heating treatments killednearly80%ofclumpssmallerthan180cmandreducedtheaveragesizeofsurvivingclumps to less than 50 cm (Ward et al.2010).Weanticipatethatthereductioninbarberryabundanceandsizewillfacilitaterecruitment of native woody herbaceousspeciesinforestunderstories,providedthatdeerpopulationsarenottoohigh.

Our results indicate thatbarberrycanbeeffectivelyreducedusingpropanetorches,with a first treatment applied anytimebetweensixweeksbeforeandonemonthafter full leaf expansion, and a secondtreatment applied six weeks later. Theimportance of follow-up treatments cannot be over-emphasized. While a singletreatmentreducedbarberryabundanceby89% (Figure 3), an earlier study notedthat 71% of clumps larger than 150 cmsurvived a single directed heating treat-mentcomparedwithonly29%ofsimilarclumpsthatweretreatedtwice(Wardetal.2010).Becausebarberryisabletoreplacecarbohydratereserveswithinonemonthofleafout(Richburg2005),follow-uptreat-ment is essential to reduce the capacity

ofthisspeciestore-occupythesiteafterinitiation of control measures. Survivingclumpscancontinuetogrowinlowlightlevels (Harrington et al. 2004) and thenspreadby layering (Ehrenfeld1999;De-GasperisandMotzkin2007).

Observationsonourresearchplotssuggestthepropanetorchesmightprovideeffec-tive control for burningbush (Euonymus alatus (Thunb) Siebold) and Japanesestiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum (Trin)A. Camus), but not Asiatic bittersweet(Celastrus orbiculatusThunb.),swallow-wort (Cynanchumspp.),or species thatrootsuckersuchasAilanthus.Wealsoob-serveddirectedheating,prescribedburning,andmechanicalcuttingwerelesseffectiveforcontrollingbarberryandotherinvasivespeciesinlargecanopygapsthaninsmallgapsorunderintactcanopy.

Becausepropanetorchesproducea1100oCflame,theyareinherentlydangeroustools,likechainsaws,thatmustbetreatedwithrespectandoperators shouldhave safetytrainingbeforeuse.Wetrainedallperson-nel in safe and efficient operation, andensuredpropertechniqueswereunderstoodandfollowedbeforeallowingindependentuseofequipment.Atleasttwopersonnelwereon site in caseof an accident.Theuse of open flame in the forest has therisk of igniting a wildfire.We mitigatedthis risk by only using torches on dayswhentheleaflitterwasdamporwet,andhadappropriatehandtoolsandbackpackwaterpumpsonhandforfiresuppression.Thisprovidedanopportunity to conductfieldworkduringinclementweatherwhenotheractivitiesarerestricted.Othersafetyconcernsincluded,butarenotlimitedto,trippinghazardsandexposure to smoke,especially smoke from poison ivy (Toxi-codendron radicans (L.)Kuntze).

High labor costs are another limitationof directed heating (Figure 6).This costcan be greatly reduced in areas whereherbicidescannotbeusedbysubstitutingmechanicalcuttingwithabrush-sawastheinitialtreatment.Anotheralternativewouldbe to use heavy equipment to smash orcutclumps,butcaremustbeexercisedtominimizedamagetosoilandnativeveg-etation(Wardetal.2009).Thetradeoffis

Figure5-EstimatedJapanesebarberryheights(SE)beforetreatmentsandinfollowingOctober.ValueswithsamelettersabovehorizontallineswerenotfoundsignificantlydifferentusingTukey’sHSDtestatP<0.05.

Volume 31 (2), 2011 Natural Areas Journal 161

lowermortalityofbarberryclumpsusingbrush-sawsthanwhenpropanetorchesareused(Wardetal.2010).Anotherproblemis that propane pressure decreased afterlessthanonehourofcontinualusage.Thisbothreducedtheflameintensity–increas-inglaborcostswithoutincreasingpropaneuse–and required periodic switching be-tween tanks. However, this provided forperiodic breaks that reduced mental andphysicalfatigue.

The benefits of controlling barberry gobeyondrestorationofnativeplants.Rela-tive to forests with a native shrub layer,enhanced levelsofblackleggedor ‘deer’ticks were found in areas dominated byinvasive shrubs, including barberry, inMaine(Lubelczyketal.2004;Eliasetal.2006) and Connecticut (Williams et al.2009).Blackleggedtickscantransmitthecausal agents of several diseases includ-ingLymedisease(Borrelia burgdorferi),human granulocytic anaplasmosis (Ana-plasma phagocytophilum Theiler), andhumanbabesiosis(Babesia microtiFranca.;Magnarellietal.2006).Thus,controllingbarberrycanhaveapositiveimpactonhu-manhealthbyloweringtheriskofexposuretotick-bornediseases.

Directed heating will not permanentlyeliminateinvasivesfromasiteunlesstheunderlyingfactorssuchashighdeerdensi-ties(Knightetal.2009),sitedisturbance,andhighseedinputofinvasives(HendersonandChapman2006)arealsoeliminated.However,theuseofdirectedheatingwithpropane torches provides an additionaltoolthatprovidesavailablegrowingspacefortheestablishmentanddevelopmentofnativeherbaceousandwoodyspeciesforhabitat restoration projects on propertieswhereherbicideuseisrestricted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank ConnecticutChapter-TheNatureConservancyandthePropaneEducationandResearchCouncilfor financial assistance; Aquarion WaterCompanyandSouthCentralConnecticutRegionalWaterAuthorityforstudysites;andJ.P.Barsky,M.R.Short,E.Cianciola,E. Kiesewetter, G. Picard, D.Tompkins,and R. Wilcox for assistance with plotestablishment, treatment, and data col-lection.

Jeff Ward is the Chief Scientist of the Department of Forestry and Horticulture. His research has focused on long-term population dynamics of woody plants in natural areas, alternative methods of controlling invasive species, and growth response of individual trees following stand disturbance.

Scott Williams is an Assistant Scientist in Department of Forestry and Horticulture studying the impacts overabundant white-tailed deer have on natural and managed ecosystems, and interaction of invasive shrubs, rodent, and ticks on Lyme disease risk.

LITERATURE CITED

Cavanagh,J.B.,andR.R.Weyrick.1978.Weedburnerforcontrollingundesirabletreesandshrubs.JournalofForestry76:472-473.

Collier,M.H., andJ.L.Vankat.2002.Dimin-ishedplant richnessandabundancebelowLonicera maackii,aninvasiveshrub.Ameri-canMidlandNaturalist147:60-71.

D’Antonio, C.A., and L.A. Meyerson. 2002.Exoticplantspeciesasproblemsandsolu-tionsinecologicalrestoration:asynthesis.RestorationEcology10:703-713.

D’Appollonio,J.1997.Regenerationstrategiesof Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergiiDC)incoastalforestsofMaine.M.S.thesis,UniversityofMaine,Orono.

DeGasperis, B.G., and G. Motzkin. 2007.Windows of opportunity: historical andecologicalcontrolsonBerberis thunbergiiinvasions.Ecology88:3115-3125.

Ehrenfeld,J.G.1997.Invasionofdeciduousfor-estpreservesintheNewYorkmetropolitanregionbyJapanesebarberry(Berberis thun-bergiiDC).JournaloftheTorreyBotanicalSociety124:210-215.

Ehrenfeld,J.G.1999.StructureanddynamicsofpopulationsofJapanesebarberry(Berberis thunbergiiDC.)indeciduousforestsofNewJersey.BiologicalInvasions1:203-213.

Ehrenfeld, J.G., P. Kourtev, and W. Huang.2001.Changes insoil functionsfollowinginvasions of exotic understory plants indeciduousforests.EcologicalApplications11:1287-1300.

Elias, S.P., C.B. Lubelczyk, P.W. Rand, E.H.Lacombe,M.S.Holman,andR.P.Smith,Jr.2006.Deerbrowseresistantexotic-invasiveunderstory: an indicator of elevated hu-

Figure6-Labor(hour/ha)byestimatedpre-treatmentabundance(%)neededforinitialandfollow-upJapanesebarberrycontroltreatments.

162 Natural Areas Journal Volume 31 (2), 2011

manriskofexposuretoIxodes scapularis(Acari:Ixodidae)inSouthernCoastalMaineWoodlands.JournalofMedicalEntomology43:1142-1152.

Gubanyi, J.A, J.A.Savidge,S.E.Hygnstrom,K.C. VerCauteren, G.W. Garabrandt, andS.P.Korte.2008.Deerimpactonvegetationinnatural areas in southeasternNebraska.NaturalAreasJournal28:121-129.

Hale, C.M., L.E. Frelich, P.B. Reich, and J.Pastor.2008.Exoticearthwormeffectsonhardwoodforestfloor,nutrientavailabilityandnativeplants:amesocosmstudy.Oeco-logia155:509-518.

Harrington,R.A.,J.H.Fownes,andT.M.Cas-sidy. 2004. Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) in forest understory: leaf andwhole plant responses to nitrogen avail-ability. American Midland Naturalist151:206-216.

Henderson, D.C., and R. Chapman. 2006.Caragana arborescens invasion inElk Is-landNationalPark,Canada.NaturalAreasJournal26:261-266.

Honu, Y.A.K., S. Chandy, and D.J. Gibson.2009.Occurrenceofnon-nativespeciesdeepin natural areas of the Shawnee NationalForest, southern Illinois, U.S.A. NaturalAreasJournal29:177-187.

Hough-Goldstein,J.,M.A.Mayer,W.Hudson,G.Robbins,P.Morrison,andR.Reardon.2009. Monitored releases of Rhinoncomi-mus latipes(Coleoptera:Curculionidae),abiological control agent of mile-a-minuteweed (Persicaria perfoliata), 2004–2008.BiologicalControl51:450-457.

Knight,T.M.,J.L.Dunn,L.A.Smith,J.Davis,andS.Kalisz.2009.DeerfacilitateinvasiveplantsuccessinaPennsylvaniaforestunder-story.NaturalAreasJournal29:110-116.

Kourtev,P., J.G.Ehrenfeld,andW.Z.Huang.1998. Effects of exotic plant species onsoil properties in hardwood forests ofNewJersey.Water,Air,andSoilPollution

105:493-501.

Kourtev,P.,W.Z.Huang,andJ.G.Ehrenfeld.1999. Differences in earthworm densitiesandnitrogendynamicsinsoilsunderexoticand native plant species. Biological Inva-sions1:237-245.

Lubelczyk,C.B.,S.P.Elias,P.W.Rand,M.S.Holman, E.H. Lacombe, and R.P. Smith.2004.HabitatassociationsofIxodes scapu-laris(Acari:Ixodidae)inMaine.Environ-mentalEntomology33:900-906.

Luken,J.O.,andD.T.Mattimiro.1991.Habitat-specificresilienceoftheinvasiveshrubAmurhoneysuckle (Lonicera maackii) duringrepeatedclipping.EcologicalApplications1:104-109.

Magnarelli,L.A.,K.C.Stafford,III,J.W.IJdo,andE.Fikrig.2006.Antibodies towhole-cell or recombinant antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi,Anaplasma phagocytophilum,andBabesia microti inwhite-footedmice.JournalofWildlifeDiseases42:732-738.

Miller, K.E., and D.L. Gorchov. 2004. Theinvasive shrub,Lonicera maackii, reducesgrowth and fecundity of perennial forestherbs.Oecologia139:359-375.

Neter, J., and W. Wasserman. 1974.Appliedlinearstatisticalmodels.Irwin,Inc.,Home-wood,Ill.

Obeso, J.R., and M.L.Vera. 1996. Resprout-ingafterexperimentalfireapplicationandseed germination in Erica vagans. Orsis11:155-163.

Richburg,J.A.2005.Timingtreatmentstothephenologyofrootcarbohydratereservestocontrolwoodyinvasiveplants.Ph.D.diss.,UniversityofMassachusetts,Amherst.

Schall,M.J.,andD.D.Davis.2009.Verticilliumwilt of Ailanthus altissima: susceptibilityof associated tree species. Plant Disease93:1158-1162.

SilanderJ.A.,andD.M.Klepeis.1999.Theinva-sionecologyofJapanesebarberry(Berberis thunbergii)intheNewEnglandlandscape.BiologicalInvasions1:189-201.

Tempel,D.J.,A.B.Cilimburg,andV.Wright.2004.Thestatusandmanagementofexoticand invasive species in National WildlifeRefuge Wilderness areas. Natural AreasJournal24:300-306.

[USDA, NRCS] U.S. Department of Agri-culture, Natural Resources ConservationService. 2010. The PLANTS Database.NationalPlantDataCenter,BatonRouge,La. Available online <http://plants.usda.gov>.Accessed2May2010.

Vitelli,J.S.,andB.A.Madigan.2004.Evalua-tionofahand-heldburnerforthecontrolofwoodyweedsbyflaming.AustralianJournalofExperimentalAgriculture44:75-81.

Ward,J.S.,S.C.Williams,andT.E.Worthley.2010. Effectiveness of two-stage controlstrategies for Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergiiDC)variesbyinitialclumpsize.Invasive Plant Science and Management3:60-69.

Ward,J.S.,T.E.Worthley,andS.C.Williams.2009.ControllingJapanesebarberry(Ber-beris thunbergii DC)insouthernNewEng-land,USA.ForestEcologyandManagement257:561-566.

Webster,C.R.,M.A.Jenkins,andS.Jose.2006.Woodyinvadersandthechallengestheyposetoforestecosystemsin theeasternUnitedStates.JournalofForestry104:366-374.

Williams, S.C., J.S. Ward, T.E. Worthley,and K.C. Stafford, III. 2009. ManagingJapanesebarberry(Ranunculales:Berberi-daceae)infestationsreducesblackleggedtick(Acari:Ixodidae)abundanceandinfectionprevalencewithBorrelia burgdorferi(Spiro-chaetales:Spirochaetaceae).EnvironmentalEntomology38:977-984.

Wilson,L.M.,M.Schwarzlaender,B.Blossey,andC.B.Randall.2004.Biologyandbiologi-cal control of purple loosestrife. FHTET-2004-12, U.S. Department ofAgriculture,Forest Service, Forest Health TechnologyEnterpriseTeam,[Morgantown,W.Va.]

Related Documents

![Los Angeles County Drought tolerant Plant List · Berberis nevinii [Mahonia n.] Nevin’s barberry √ shrub Berberis pinnata California Barberry √ √√ shrub Berberis thunbergii](https://static.cupdf.com/doc/110x72/5f278dffde178e4d933fb75a/los-angeles-county-drought-tolerant-plant-list-berberis-nevinii-mahonia-n-nevinas.jpg)