-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

1/15

Contra Coercion: Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, and Negotiated Institutional Change

Author(s): Pauline Jones Luong and Erika WeinthalSource: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 98, No. 1 (Feb., 2004), pp. 139-152Published by: American Political Science AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145302

Accessed: 04/04/2010 16:26

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=apsa.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The American Political Science Review.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145302?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=apsahttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=apsahttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/4145302?origin=JSTOR-pdf -

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

2/15

American PoliticalScience Review Vol. 98, No. 1 February2004

C o n t r a C o e r c i o n : R u s s i a n T a x R e f o r m , E x o g e n o u s S h o c k s ,a n d N e g o t i a t e d Institutional C h a n g ePAULINE JONES LUONG Yale UniversityERIKA WEINTHAL TelAviv Universitye view of institutions as coercion rather than as contracts dominates the comparative politicsiterature on both institutional creation and thepolitics of economic reform. The emergence of acollectively optimal tax code in Russia demonstrates the limitations of this emphasis on coercion.This new tax code was not imposed by a strong central leader,mandated by international institutions,orthe result of state capture by powerful economic interestgroups. Rather, it is theproduct of a mutuallybeneficial exchange between the Russian government and the Russian oil companies. Russia's ability tonegotiatean effective taxregimealso suggests theconditions under which and the microcausal mechanismwhereby exogenous shocks promote institutional change and economic reform. Owing to their mutualvulnerabilityand interdependence,the August 1998 financial crisis generated widely shared perceptionsamong these actors thatthepayoffs of cooperation had changed. Yetthe economic reform institutionthatresulted requireda series of incrementalstrategicmoves that established common knowledge.A t the core of politicalscience is the questionof how institutions emerge-that is, whetherthey are the product of social contracts andstrategic bargains,power asymmetries and coercion, orpath dependence and evolutionary development. In-deed, although each subfield has favored a differentperspective on institutional emergence, this is one ofthe central questions that unifies them.The view of institutions as contracts (or the contrac-tarianapproach), which was born with Thomas Hobbesbut reached its maturity in the public choice and ratio-nal choice literature, has dominated American politics(see, e.g., Kiewiet and McCubbins 1991, Shepsle 1986,and Weingast 1993) and the new economics of orga-nization (see, e.g., Moe 1984 and Williamson 1985) foralmost two decades. According to this view, institutionsare the product of individual exchange and competi-tive selection aimed at deriving a mutually beneficialoutcome, such as efficiency or cooperation (see, e.g.,Shepsle 1986). As comparative politics embraced the

new institutionalism, however, the contractarian ap-proach was largely rejected in favor of the view of insti-tutions as coercion (see, e.g., Bates 1988,Firmin-Sellers1995, and Knight 1992).1 Despite their many differ-ences, this is true of both historical institutionalistaccounts, which clearly eschew contracting (see, e.g.,Thelen and Steinmo 1992), and rational choice institu-tionalist accounts, which have come to embrace the as-sumption that institutional outcomes are distributional(see, e.g., Knight 1998).The view of institutions as coercion rather than ascontracts has also come to dominate the literature onthe politics of economic reform. This is apparent inthe prevalence of the argument that economic policychange requires an authoritarian leader and/or a strongstate.2Based on the divergent experiences of East Asiaand Latin America, the view became widespread thatnecessary but difficultmarket reforms must be imposedfrom above-either to make effective investment de-cisions, to thwart organized opposition, or to over-come an inherent popular bias toward the status quo(see, e.g., Fernandez and Rodrik 1994, Haggard andKaufman 1992, Stallings and Kaufman 1989, and Wade1990). Alongside this literature an analogous argumentemerged regardingthe need for international pressuresto mandate or encourage market reforms (see, e.g.,Kahler 1989 and Stallings 1992), ranging from com-pensatory aid packages and International MonetaryFund (IMF) conditionality (see, e.g., Sachs 1994 andStone 2002) to the need to attract foreign capital (see,e.g., Simmons 1999).3The rejection of contractarianism

Pauline Jones Luong is Assistant Professor, Yale University, Depart-ment of Political Science, PO. Box 208301, New Haven, CT 06520-8301 ([email protected]).Erika Weinthal is Assistant Professor, Tel Aviv University,Department of Political Science, PO. Box 39040, Tel Aviv 69978 Israel([email protected]).The authors share equal responsibility for the content and analysisherein. This article is part of a long-term joint project and we havechosen to rotate authorship on the articles we generate.The authors would like to thankTimothy Colton, Anna Grzymala-Busse, Stephen Hanson, Stephen Holmes, Gregory Huber, IraKatznelson, Lawrence King, Ellen Lust-Okar, M. Victoria Murillo,Thomas Remington, Andrew Schrank,Regina Smyth, Ivan Szelenyi,Daniel Treisman,Zeev Maoz, the participantsin both the 2001-2002Post-Communist Workshop and the Comparative Politics Workshopat Harvard University, and three anonymous reviewers for their in-sightful comments and useful suggestions on early drafts, as well asMariya Kravkova and Maria Zaitseva for providing research assis-tance. We also acknowledge the Carnegie Corporation in New Yorkand the Leitner Programin Political Economy at Yale University forfinancing our fieldwork in Russia, the Institute of Law and PublicPolicy in Moscow for offering logistical support, and the CarnegieGlobalization and Self Determination Project at the Yale Center forInternational and Area Studies for facilitating our collaboration atYale University.

1 The opposite trend occurred in international relations, whichmoved from the domination of the institutions as coercion approach(Neorealism) to the institutions as contracts approach (Neoliberal-ism). For an overview of this debate, see Baldwin 1993.2 In this literature, state strength is often equated with autonomyor insulation from popular demands and narrow economic inter-ests. For example, this is why Williamson (1994) advocates the useof autonomous technocrats (or technopols) to implement economicreform in developing countries.3 These two arguments come together most explicitly in Sachs 1994,which arguesthat successful economic reformrequiresa combinationof strong (i.e., autonomous) leaders and international assistance.

139

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

3/15

ContraCoercion February2004is also manifested in the predominant treatment of eco-nomic reform as benefiting a particular group at the ex-pense of the majority rather than expanding the pie tomake everyone better off (see, e.g., Alesina and Drazen1991; Olson 1982, and Schamis 1999).

We demonstrate that this emphasis on coercion hin-ders our understanding of the process by which insti-tutional creation and economic reform occurs througha detailed analysis of the emergence of a collectivelyoptimal tax code in Russia from 1998 to 20024 basedon extensive elite interviews. 5 Following the SovietUnion's retreat from Eastern Europe in the late 1980sand ultimate demise in 1991, scholars also endorsedthe view of institutions as coercion in their attemptsto understand institutional emergence and evaluatethe prospects for market transition in the postcommu-nist world (see, e.g., Hellman 1998, Stone 2002, andTreisman 1998). We find, however, that this new taxcode was neither imposed by a strong central leader,mandated by international institutions, nor the resultof state capture by powerful economic interest groups,as both the general literature predicts and specialistson Russia commonly argue. Rather, it represents anegotiated settlement between the Russian govern-ment and the most powerful set of domestic eco-nomic actors-the Russian oil companies (ROCs)--in which each side incurred gains and losses from theexchange.At the same time, the emergence of an effective taxregime in Russia at the end of a decade marred bystagnant reform efforts offers an important correctiveto the contractarian approach because it suggests an al-ternative mechanism whereby two equally powerful ac-tors can achieve mutual gains from cooperation. Owingto their mutual vulnerability and interdependence, theAugust 1998 financial crisis generated widely sharedperceptions among the Russian government and theROCs that the payoffs of cooperation had changed. Theeconomic reform institution that resulted, however,was contingent upon a series of incremental strate-gic moves that established common knowledge. Thus,we also build on the literature that invokes exogenousshocks to explain economic reform by clearly specifyingthe conditions under which and the microcausal mecha-nism whereby exogenous shocks promote institutionalcreation and economic policy change.

THEPUZZLEOF RUSSIA'S NEGOTIATEDTAXREFORMRussia's ability to negotiate a new tax code after almosta decade of abortive attempts presents us with astrikingpuzzle in light of both the dominance of the coercionapproach in comparative politics and the widespreadpessimism about Russia's prospects for market reform.First, it directly contradicts the view of institutions ascoercion whereby difficult economic reforms can onlybe imposed from above by a strong leader within orexternal pressures from outside the country. Second,both the recent literature on economic reform in post-communist states and the long-held conventional wis-dom on resource-rich states predict that Russia willfail to develop the necessary institutions to promoteeconomic growth, particularly a stable and compre-hensive tax regime. Finally, the mechanisms that havebeen posited to facilitate cooperation elsewhere-suchas a precommitment strategy and social norms-wereclearly absent in this case.From InformalExchange to FormalGuaranteesTax policy in Russia for most of the 1990s can bestbe described as a classic collective action problem7in which the two most powerful actors concerned-the Russian government and the Russian oil compa-nies (hereafter ROCs)-followed individually rationalstrategies that were collectively suboptimal.8 Owing tomutual suspicion and weak enforcement, the Russiangovernment opted to maximize its revenue in the shortterm through setting arbitrarily high tax rates by de-cree and the ROCs opted to minimize their tax burdenin the short term by developing increasingly elaborateschemes to evade these exorbitant tax rates. As a result,the government was able to collect approximately halfof its projected tax revenues and the ROCs could keep asubstantial portion of their profits.Both sides, however,incurred heavy costs over the long term in the form ofunreliable revenue streams, insecure property rights,and asymmetrical information that had a negative ef-fect on the Russian economy as a whole and could havebeen reduced or eliminated through cooperation.From the Russian government's perspective, partic-ularly the Ministry of Finance, maintaining high taxrates was the best way to replenish the budget despitelow compliance rates (see, e.g., RPI, March 1996 and

4 The new Russian tax code consists of two parts.Part I was adoptedin July1998 and enacted in January1999;it covers administrativeandprocedural matters, including the introduction of new taxes and theprotection of taxpayers' rights.Part II was adopted in August 2000,amended in November and December 2001, and enacted in 2001 and2002; it includes specifications on various taxes, including the VAT,corporate profits tax, personal incomes tax, and the social tax. Thisarticle focuses primarily on explaining Part II, although Part I laidthe groundwork for the approval and implementation of Part II. Foran overview see, OECD 2001, 115-144.5 These interviews were carriedout systematically in Moscow fromSeptember 2001 to July2002 with representatives from both Russianand foreign oil and gas companies, Russian government officials,and Russian and foreign financial and energy experts. In most cases,names are withheld at the request of the interviewee.

6 Russia not only possesses the world's largest natural gas reservesand the eighth largest oil reserves, but is the world's largest ex-porter of natural gas and the second largest exporter of oil. Seehttp://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/russia.html.7 For a comprehensive discussion of collective action problems, seeHardin 1982 and Olson 1965.8 Although other actors (such as regional leaders) were also influen-tial in shaping taxation policy in the early 1990s,we focus our analysison the ROCs and the Russian government because they were themost important actors involved in the subsequent formulation of thenew tax code-particularly PartII (authors' personal communicationwith Alexander Ustinov, Economic Expert Group, June 2002).

140

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

4/15

American Political Science Review Vol. 98, No. 1

Samoylenko 1998).9 The official tax rates for industryand revenue sharing for regions that existed on paperwere rarely, if ever, observed in practice, and tax col-lection rates were abysmally low as a result (Gustafson1999, chap. 9; Shleifer and Treisman2000, chap. 6). Ac-cording to the IMF (2000, 69,71), even as of January1,2000, the value of unpaid taxes at the consolidated level(federal and local governments) was 8.3% of the GDP.Instead, economic elites presiding over the country's in-dustrial enterprises as well as regional leaders engagedin ongoing negotiations with the government to de-termine their respective tax burdens (see, e.g., Easter,2002). Not surprisingly, the government purposefullytargeted the highly lucrative and concentrated indus-tries in the energy sector for revenue extraction andits budget was highly dependent on this sector as a re-sult. In 1998, for example, the oil sector accounted forapproximately one-fourth of all tax revenues (RussianEconomic Trends 1998, 6). The Russian governmentwas able to collect at least a portion of the revenue itsought from this particular sector by raising tax ratesarbitrarilyand threatening to employ different coercivemeans, such as blocking access to pipelines and exportmarkets, if companies did not comply. Moreover, re-sponsibility for determining tax rates in the energy sec-tor was often shared by the Ministryof Fuel and Energyand the Ministryof Finance, which resulted in constantfluctuations in the tax rates, especially pertaining to ex-cise taxes. Despite the high transaction costs involvedin revenue extraction, the Russian government, nev-ertheless, managed to collect between 33 and 35% ofthe ROCs' revenues based on a statutory tax rate of53%.10At the same time, the government could guar-antee itself a source of fuel by arbitrarilygranting taxarrearsto companies in exchange for providing energyto delinquent customers, which often included domes-tic industries as well as households (Jones Luong 2000).Yet this strategy only exacerbated the problem ofnoncompliance, particularly among the ROCs, by cre-ating a strong incentive for economic actors to hidetheir profits. It also failed to take into account thatthe ROCs' tax burden was much higher than even thegovernment projected because of the regional and localgovernments' tendency to levy informal taxes on the oilcompanies operating in their regions by forcing them toprovide social services and infrastructure investments(Gustafson 1999, 207). The ROCs responded to thisuntenable situation by developing a series of legal andsemilegal schemes to hide their profits through whichthey effectively evaded heavy taxation.11Transferpric-ing was the most common form. Because the corporate

income tax (or profits tax) was based on trade ratherthan production, parent companies could reduce theirofficial income by creating trading subsidiaries (oftenlocated in a low taxzone within Russia) from which theypurchased oil at below-market prices and then resoldthis oil at equally low prices to offshore Russian inter-mediaries (often located in a free-trade zone). By someestimates, the ROCs have been able to hide at least 25 %of their export proceeds through transfer pricing.12Asa result, the government only received 22% of the ap-proximately $30 billion in windfall rent from natural re-sources sales in 2000, while 78% remained in the handsof oil and gas exporters.13Actual (versus statutory) taxrates on oil not only were lower than they should be, butalso differed markedly from company to company (see,e.g., Novaiia gazeta, August 7, 2000). Another form oftax evasion that detracted from profit-making activitiesincluded the development of intricate schemes to avoidpayroll taxes. Here, parent companies would createoffshore subsidiaries to pay their employees, arrangefor insurance companies to pay their employees underthe guise of large monthly payouts from life insurancepolicies, or pay higher corporate banking fees so thatemployees would earn higher interest rates than themarket rate on their checking accounts.14Thus, by the end of the 1990s the Russian govern-ment and the ROCs were locked in a vicious cyclein which exorbitant tax rates encouraged evasion andevasion encouraged even higher tax rates and threatsof expropriation, leading to more elaborate and time-consuming schemes to hide profits. The results weredisastrous for the Russian economy on the whole, whichdid not record positive investment rates or economicgrowth for most of the decade (IMF, 2000). Althoughthe government had attempted to introduce new taxlegislation since 1995, it was continuously stalled inthe Duma due to the opposition of the "Left" (i.e.,the Communists and Yabloko) and of the oil and gaslobby, which the Yeltsin administration attempted tocircumvent by issuing new decrees. Even as late asApril1998, the Duma and the government could not reachan agreement concerning tax reform. Rather, the for-mer continued to impede reformby adopting numerousamendments, while the latter refused to compromiseby addressing procedural issues related to taxpayers'rightsor lowering the tax burden (see, e.g., Samoylenko1998). Similarly, in addition to blocking tax reform inthe Duma, the ROCs continued to hide their income,to exaggerate their losses in order to obtain tax breaks(RPI, April 1998, 10) and to pressure the governmentto reduce the energy sector's tax burden (RFE/RL,July 23, 1998).This situation, however, changed dramatically by theend of 1998. Despite nearly a decade of failed tax re-form, from 1998 to 2002 the Russian government and

9 This was also confirmed in authors' personal communication withArkady Dvorkovich, Deputy Minister,Ministry of Economic Devel-opment and Trade,July 5, 2002.10 Authors' personal communication with Vitaly Yermakov, Re-search Associate, Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA),June 2002, and with Dvorkovich, op. cit.11Although the Russian government's auditors and the Ministry ofFinance could ascertain a close estimate of what the ROCs' actualprofits were through export quotas and yearly audits, the prevalenceof these legal and semilegal schemes made it extremely costly tocatch or to sanction the ROCs for tax evasion (authors' personal

communication with representatives of ROCs, September 2001 andJune-July 2002, and with tax auditors, July 2002).12Authors' personal communication with Yermakov, op. cit.13Authors' personal communication with Yermakov, op. cit.14Authors' personal communication with Peter I. Reinhardt,Principle, Ernst & Young, September 2001.

141

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

5/15

Contra Coercion February2004the ROCs were able to achieve mutual gains from co-operation in the form of a new tax code. In sum, thisnew tax code is designed to increase the reliability ofrevenue streams for both sides by creating incentivesfor broad-based tax compliance without a significantimprovement in the government's administrative ca-pacity and pegging the ROCs' tax payments to fluctua-tions in the global price of oil. It also reduces informa-tion asymmetries by eliminating transfer pricing andencouraging the ROCs to disclose their actual profits.By setting fixed tax rates and reducing incentives forthe government to resort to coercive tactics to meetits revenue needs, moreover, the new tax code has thepotential to secure property rights for the ROCs andthereby enable them to both increase their investmentsat home and attract foreign partners to expand theiroperations abroad.Furthermore, it puts Russia decisively on the pathtoward market reform. By most accounts, Russia's newtax code exceeds Western standards not only becauseit sets lower tax rates than the OECD recommends butalso because it is much simpler and clearer than the pre-vious one. For example, it has introduced a 13% flat taxon personal income, capped corporate contributions tothe social insurance fund, reduced the profits tax (a.k.a.corporate income tax) rate from 35 to 24%, abolishedturnover taxes (as of 2003), tied export tariffs directlyto the price of oil, and established new accounting pro-cedures that are on par with international accountingstandards.In addition, a new mineral extraction tax wasintroduced in January2002 (Chap. 26, Part II) as a flatrate pegged to the price of oil. It has also won the praiseof foreign and domestic financial and political analystsfor the inclusive nature of tax benefits and, thus, its po-tentially positive impact on the Russian economy as awhole (see, e.g., Andersen 2002 and Rabushka 2002).15These assessments were confirmed by the initial re-sults, which indicate that tax collection rates have in-creased since the new code was put into effect (see, e.g.,Kommersant, October 19, 2001; Pravda, October 18,2001; and Russia Journal, July 18, 2002). For example,the fact that income tax revenues jumped by 70% fol-lowing the introduction of the flat tax on personal in-come has been directly attributed to the abandonmentof costly tax-evasion schemes (Aslund 2001, 22).The Failureof ExistingAccounts: Coercion,State Capture,and the "ResourceCurse"How did the Russian government and the ROCs man-age to overcome their collective action problem andcooperate with one another to their mutual advantage?This outcome is especially puzzling because none ofthe existing accounts provide a satisfactory explana-tion. Neither the general predictions nor the particu-lar assessments of Russia that stem from the predom-inant view of institutions as coercion can explain theemergence of this new tax code as a product of intense

negotiation and compromise. Indeed, both the litera-ture on institutional emergence generally and that oneconomic reform in postcommunist states specificallypredict that Russia should fail to establish a viable taxcode-either through contracting or at all. Nor werethe mechanisms often cited in contractarian explana-tions of institutional emergence through cooperationpresent in this case.That the view of institutions as coercion has dom-inated scholarly assessments of Russia's transition isclearly demonstrated in the overwhelming pessimismconcerning its prospects for economic reform in the ab-sence of either a strong leader within or external pres-sures from outside the country. Many have attributedmarket failure in Russia throughout most of the 1990sto the weakness of either President Boris Yeltsin or cen-tral state institutions vis-a-vis powerful economic inter-ests (see, e.g., Hellman 1998, McFaul 1995, Reddawayand Glinski 2001, and Robert and Sherlock 1999).Thus, not surprisingly, Russia's hope for establishingthe political order necessary to achieve market reformhas often been placed in its newly elected president,and seemingly more authoritarian leader, VladimirPutin, who succeeded Yeltsin in March 2000 (see, e.g.,Nicholson 2001 and Shevtsova 2003).16 Because henot only enjoyed a popular mandate but also faceda Duma that was less polarized, and therefore morepliable, after the 1999 elections Putin seemed poisedto unilaterally redefine Russia's political climate andsingle-handedly push through his economic agenda(see, e.g., Remington 2001). Putin's position as formerhead of the Soviet Union's internal security service (i.e.,the KGB) bolstered the presumption that he wouldbe a strong leader, capable of using force to imposehis will.

According to this perspective, the new tax code isbest understood as yet another example of Putin's unri-valed authority since his election. Almost immediatelyafter ascending to the presidency, for example, Putinlaunched sweeping administrativechanges aimed at re-ducing the power of the regions to influence nationalpolicy-making, including tax reform. The most signifi-cant of these was the reorganization of the FederationCouncil, through which the regional leaders had pre-viously obstructed the government's attempts at taxreform and weakened the federal budget by demand-ing complex revenue-sharing arrangements (see, e.g.,Treisman 1999). Putin also demonstrated to the ROCsthat he was willing to use force through his decisivetreatment of the notorious oligarchs Boris Berezovskyand Vladimir Gusinsky in the first few months of hispresidency (see Lloyd 2000 for details). Yet, if this iswhat brought the ROCs to the bargaining table, it failsto explain why negotiations over a new tax regime be-gan in late 1998 under Yeltsin.

15 This is the consensus among domestic and foreign financial an-alysts according to authors' personal communications, September2001 and June-July 2002.

16 Putin was appointed as prime minister in August 1999 and thenelected to the presidency in March 2000 with 52.94% of the vote(RFE/RL Russian Election Report, 2000, 13). The Duma elected inDecember 1999 contained amajorityof his supporters,who appearedto form the first stable policy coalition in the Russian parliament(the Unity bloc). For details, see Colton and McFaul2000 and Smyth2002.

142

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

6/15

AmericanPolitical Science Review Vol. 98, No. 1It also fails to explain why Putin did not simplyimpose a new tax regime that solely reflected thegovernment's preferences. With the elimination of thetwo biggest obstacles to tax reform in the 1990s-thepolarized Duma and recalcitrant regional leaders-

perhaps Putin could have passed the new tax code with-out even the tacit approval of the ROCs. He also couldhave continued Yeltsin's arbitrarypractice of changingtax ratesby decree. Yet Putin chose to forfeit this partic-ular advantage vis-a-vis the ROCs and, instead, to con-tinue the negotiations and make the necessary compro-mises so that a comprehensive tax code could be passedthrough the Duma as a law that was endorsed by thecountry's most important taxpayers-the ROCs.'7 Aswill be described in more detail below, to reassure theROCs that their assets would not be expropriated afterthe 1998 crisis,he also publicly recognized the propertyrights of the oil industry and pledged his commitmentnot to renationalize. Thus,he seemed to be interested inmaking a truce with the remaining oligarchs rather thanalienating them. Moreover, despite signs of economicgrowth and increased tax revenues in 1999, agreeingto formalize a tax code with lower fixed rates was notcostless for Putin. If the ROCs chose to renege on theircommitment to comply with the lower tax rates, theRussian government risked a budget deficit because itcould no longer arbitrarilyraise tax rates.Others have looked to the international communityto provide either the financial incentive or direct pres-sure to propel market reform in Russia and other post-communist states (see, e.g., Aslund 2002, Sachs 1994,and Stone 2002). Indeed, the undeniable importanceof international competitiveness and the increasinglydirect role of transnational actors in domestic affairs inthe context of globalization (Rodrik 1997) and a post-Cold War world (Weinthal 2002) lend support to thisargument. Thus, an obvious alternative explanation forthe new tax code is that the government pushed throughthis new tax regime in order to attract foreign invest-ment or appease its foreign creditors. Yet it has beenclear since independence that, particularly in the en-ergy sector, Russia has very little interest in bringing indirect foreign investment (Jones Luong and Weinthal2001). In fact, until very recently, both the executivebranch and the Duma have stalled the adoption ofPSAs, which areuniversallyviewed as the key to furtherforeign investment in the energy sector.18 As will be-come clear in the following section, the Russian govern-ment also did not adopt a new tax regime to attract for-eign direct investment but, rather, because the ROCssought an additional guarantee for their property rightsat home by attracting Western partners for joint ven-tures abroad. Nor is the new tax code simply a productof direct pressure from foreign financial consultants orthe IMF compelling the Russian government to designa more suitable (i.e., Western-style) tax regime. In fact,

since 1997 the IMF has been encouraging the Ministryof Finance to raise, not lower, Russia's tax rates.19The contractarian approach has also been rejectedin the form of two prominent and closely related ap-proaches to understanding the failure of economic re-form in postcommunist states. The first is the "winnertake all"view, according to which a narrow set of actorscaptured the gains from early market reforms by virtueof their position and then effectively prevented sub-sequent reforms that might threaten these early gains(Hellman 1998).For Russia, in particular, this perspective is directlyrelated to what many have deemed the evils of "insiderprivatization" (or privatization policies that deliber-ately favor those closest to the regime), because it eitherenriches a few agents who prefer to maintain insecureproperty rights so that they can exploit their privilegedaccess to social assets (Sonin 1999) or creates "earlywinners" who block subsequent reforms that wouldthreaten their ability to continue to reap the benefits oftheir ill-gotten gains (Alexeev 1999; Black, Kraakman,and Tarasova 2000). The most notorious "early win-ners" are the ROCs because of the way in which thesewell-positioned private actors acquired ownership ofthe energy sector-first, through a pure "asset grab"and, then, through a suspicious "loans for shares" deal(see Johnson 1997 and McFaul 1995 for details). Byagreeing to the new Russian tax code, however, theROCs do not "take all" but, rather, incur substantialeconomic losses. Despite reduced tax rates, the newtax code actually increases their tax burden becauseit eliminates the tax benefits of transfer pricing andcapital expenditure deductions.20Even when oil pricesbegan to recover, moreover, the ROCs chose to con-tinue negotiations with the Russian government and tobring their profits onshore rather then reverting backto tax evasion.More specifically, according to this perspectiveRussia's inability to develop a viable tax regime thusfar has also been attributed directly to this elite "re-distribution of power resources" following the Sovietcollapse (Easter 2002). The new Russian tax code, how-ever, demonstrates not only that the ability of eco-nomic elites to derail the economic reform process ismore limited than these pessimistic accounts suggestbut also that, under certain conditions, these "insiders"or "early winners" can in fact serve as the engine offurther reform.The second is the view of the Russian state as fully"captured" by key economic interests. The tax code,then, is merely the result of "state capture"-that is,the ROCs have used their excessive political influenceto impose lower tax rates for their own benefit. Yetthis is an unsatisfactory portrayal of the emergenceof the new tax code for several reasons. First, if theROCs were capable of simply dictating their preferredpolicies to government officials, it is not clear why theywould prefer to establish a formal tax regime rather17 According to the 1993 Russian Constitution, taxation is under thepurview of the legislature;thus,a comprehensive tax code could onlybe adopted as a law.18 Authors' personal communications with Vladimir Konovalov,Director, Petroleum Advisory Forum, September 14, 2001.19 Authors' personal communication with Dvorkovich, op. cit.20 Authors' personal communication with Yermakov,op. cit.;see alsoMazalov 2001, 2.

143

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

7/15

ContraCoercion February2004than continuing to benefit from the status quo in whichthey relied on informal networks and influence both tonegotiate favorable tax rates and to evade unfavorabletaxes. It also does not explain why the ROCs endorseda tax code that inflicted short- and long-term costs onthem by forcing them to fully disclose their profits,adopt accounting procedures, and accept an overall in-crease in their tax burden. Second, the literature on"state capture" predicts that those who benefit froma "capture economy" will reject institutions that dis-perse rents (Hellman, Jones, and Kaufman 2000) orimprove the protection of property rights (Sonin 1999).Yet by protecting tax payers rights vis-a-vis state agen-cies, lowering rates for all taxpayers, and endeavoringto increase compliance across sectors and broaden thetax base, the new Russian tax code does both. It thusprovides tax benefits that are inclusive in nature and isalready having a positive impact on the Russian econ-omy as a whole.

Beyond the literature on institutional emergence andthe politics of economic reform, the long held con-ventional wisdom on resource-rich states also predictsthat Russia will fail to develop the necessary institu-tions to promote economic growth, particularlya stableand comprehensive tax regime. In the vast literatureon the "resource curse," a weak (or nonexistent) taxregime is viewed as perhaps the most prevalent nega-tive outcome of resource wealth due to state leaders'myopic thinking and heavy reliance on external (i.e.,rather than internal) sources of revenue (see, e.g., Karl1997, Mitra 1994, and Shafer 1994). The emergence ofa viable tax code in energy-rich Russia, therefore, is astriking anomaly.

Finally,Russia's ability to achieve mutual gains fromtrade in the form of a new tax code is also puzzlingbecause the causal mechanisms that are commonly in-voked in the literature to explain cooperation-such asa precommitment strategy21 or social norms (e.g., focalpoints)22-were clearly absent in this case.Neither the Russian government nor the ROCs wereunilaterally willing to make an extreme strategic moveto signal their commitment to cooperation. Rather,each party continued to pursue independently ratio-nal strategies. For example, even when oil prices weredeclining in early 1998, rather than easing the tax bur-den on the ROCs, the government sought to squeezethe ROCs for additional taxes to cover the gaps in thegovernment budget (RPI, June/July 1998). Likewise,the ROCs' strategy to exaggerate their losses to obtaintax breaks only added to the level of mutual distrustbetween the ROCs and the Russian government (RPI,April 1998).23Moreover, the persistence of the behavioral normsand informal networks that guided elite behavior in the

Soviet period actually contributed to their incentivenot to cooperate rather than serving as a focal pointto overcome the collective action problem they faced.As noted earlier, the ROCs benefited from arbitrarilyhigh tax rates under Yeltsin because they had privi-leged access to both formal and informalpolicy-makingchannels. Throughout the 1990s, they exerted politicalinfluence through two main forms of lobbying. The firstand most common form was to influence deputies in theDuma to oppose or support proposed government leg-islation. The ROCs achieved this by either simply brib-ing deputies or supporting their own candidates (oftenformer employees) for election to the single-mandateseats.24The second form of lobbying took place throughdirect, personalized contact with members of the exec-utive branch-most importantly, the Ministry of Fueland Energy.25Many oil companies used their close re-lations with key government ministries to block whatthey considered to be unfavorable legislation, includ-ing previous versions of the tax code.26 Regardless ofthe method, however, the oil and gas lobby was highlyeffective and thus widely considered to be "one of thestrongest and most effective lobbies" in Russia.27Forthe latter part of the 1990s,this lobby convinced a suffi-cient number of deputies and government officialsto block tax reform and even to reverse unfavorablechanges made by executive decree. In March 1997, forexample, the ROCs persuaded both the Duma and thegovernment to reverse a R15,000 increase in the oilexcise tax (from R70,000 to R55,000 per ton of crude)that the Ministry of Finance and the State Tax Servicepushed through several months before (RPI, March1997).EXPLAINING OOPERATION:XOGENOUSSHOCKSANDINSTITUTIONALHANGEThe emergence of a tax regime in Russia that is bothcollectively optimal and effective not only calls intoquestion the dominance of the coercion approachto in-stitutions and economic reform in comparative politicsbut also presents us with an opportunity to refine thecontractarian approach. The fact that Russia's new taxcode was the product of a strategic exchange betweentwo sets of equally powerful actors-the Russian gov-ernment and the ROCs-aimed at mutual benefit sug-gests that the contractarian approach is more widelyapplicable beyond the United States and WesternEurope than comparativists working on develop-ing countries may have thought. At the same time,

21 A precommitment strategy occurs when one player unilaterallymakes and extreme strategic move to convince another player thathe or she is willing to abandon his or her dominant strategy andchange his or her behavior. On precommitment strategies, see, e.g.,Maoz and Felsenthal 1987.22 On focal points, see Schelling 1960.23 Authors' personal communications with Dvorkovich, op. cit., andKonovalov, op. cit.

24 Authors' personal communication with Boris Makarenko,DeputyDirector General, Center for Political Technologies, September 19,2001; Oleg Vyugin, Chief Economist, Troika Dialogue, September17, 2001; and representatives of ROCs, op. cit.25Authors' personal communications with Vladimir Konovalov, op.cit.26Authors' personal communication with Mark Urnov, Center forPolitical Technologies, September 19, 2001.27Authors' personal communication with Vadim Eskin, CERA,September 12, 2001. This sentiment was shared by other expertswhom the authors interviewed, including Makarenko, op. cit., andUrnov, op. cit.

144

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

8/15

American Political Science Review Vol. 98, No. 1however, the contractarian approach does not providea complete explanation for why these two equally pow-erful actors were able to successfully negotiate a viabletax regime after almost a decade of failed attempts. Asdiscussed in the preceding section, the mechanisms thatare most often cited to explain cooperation are clearlyabsent in this case. We offer an alternative mechanism.In short, we argue that the shock of the Augustfinancial crisis provided the impetus for institutionalcreation and economic policy change in the form of anew tax code because it generated widely shared per-ceptions among both the Russian government and theROCs concerning the benefits of cooperation and theneed for formal guarantees. These shared perceptions,however, were contingent upon both sets of actors feel-ing equally vulnerable to the effects of the crisis and rec-ognizing that they depended on one another to recoverfrom the crisis. Nor were shared perceptions alone suffi-cient to bring about institutional or economic policychange. Rather, the new tax code required that bothsets of actors possessed common knowledge,28 whichwas achieved through a series of incremental strate-gic moves. Thus, we also build on the literature thatinvokes exogenous shocks to explain change in eitherlongstanding institutions or deleterious economic poli-ces (see, e.g., Drazen and Grilli 1993, Haggard andKaufman 1997, and Krasner 1984) by clearly specifyingthe conditions under which and the microcausal mech-anisms whereby shocks induce institutional change andeconomic reform.MutualVulnerabilitynd InterdependenceAlthough its root causes were much deeper, theRussian government's decision to devalue the rubleand place a moratorium on external debt payments trig-gered the August 1998 financial crisis that sent shock-waves throughout the Russian economy: Real GDPplummeted, inflation and unemployment soared, andcommercial banks went bankrupt (see, e.g., OECD2000,33-45). This crisis,of course, was also precipitatedby the recession that spread across Asia in 1997 (or the"Asian flu") and the steep decline in world oil pricesin 1998. The immediate effects on Russia's economywere devastating, yet the political effects (and the po-tential they offer for long-term economic growth) areeven more striking. This exogenous shock enabled theRussian government and the ROCs to escape the vi-cious cycle of exorbitant tax rates and widespread eva-sion that characterized Russia's tax regime in the 1990s.In short, both sets of actors emerged from the August1998 financial crisis with the realization that the costsof their past failure to cooperate were too high.Twoconditions facilitated this change in perceptions:the mutual vulnerability and interdependence of the

Russian government and the ROCs.29Mutual vulner-ability provides both actors with an incentive to cometo the bargaining table because their own survival isthreatened. While interdependence often gives rise tocollective action problems, it also serves as the basisfor cooperation when it creates a situation in whicheach side needs the other in order to recover from aneconomic crisis.Thus, our argument contrasts with thewidespread depiction of institutional creation as bar-gains struck between kings and capitalists (or rulersand key economic actors) found in the contractarianliterature in which it is sufficient for one side to feelthreatened by the potential actions of the other (see,e.g., Levi 1988, North and Weingast 1989, and Tilly1990). It also diverges from the view that a crisis caninduce economic reform by weakening the bargainingpower of one set of actors-usually organized interests,such as labor, or the losers of reform-and strength-ening another's-usually the state or incumbents (see,e.g., Remmer 1998) or when the state is sufficientlystrong vis-ai-vis societal actors to utilize the crisis asa window of opportunity to push through unpopularreforms (see, e.g., Krueger 1993). Likewise, it differsfrom the literature that argues economic reform canonly come about after bargaining power shifts in a "warof attrition" such that one of the vulnerable socioeco-nomic groups concedes and bears most of the distribu-tional costs of the reform process (see, e.g., Alesina andDrazen 1991). Rather, both mutual vulnerability andinterdependence are contingent upon the existence ofsocioeconomic actors who are powerful enough to chal-lenge the state. Although the existence of such actorsis taken for granted in standard contractarian models,this is more often the exception rather than the rule indeveloping countries where the norm since the 1950shas been state-led development (see, e.g., Chaudhry1993).30In Russia, this is the case only because the oilsector was privatized to domestic actors in the mid-1990s (for details, see Jones Luong and Weinthal 2001).The August 1998 financial crisis, which resulted inenormous losses in profits and tax revenue to the ROCsand Russian government, respectively, revealed the ex-tent to which these equally powerful actors were bothvulnerable to global markets and, thus, the costlinessof their previous failure to cooperate. The crisis was"sobering" for the ROCs because it "forced [them] toacknowledge the cumulative negative effects of theirprevious behavior."31Following the crash in August

28 Common knowledge refers to shared information among playersconcerning the parameters and payoffs of the game. In most gametheoretic accounts, it either is assumed to exist or can be achievedwithout direct communication. See Werlang 1989.

29 While Weyland (1998, 2002) also suggests that an economic shockcan lead to a change in perception, our argument differs in two ways.First, we do not find that socioeconomic actors merely support thegovernment's reform efforts to recuperate their losses and avert fur-ther ones but, rather,that both sides have an incentive to bargainoverthe creation of economic reform institutions. Second, we take theargument that shocks cause a change in perception one step furtherby elucidating how this change in perception translates into a changein behavior among equally powerful actors, resulting in these neweconomic policies.30 In fact, this may help explain why the contractarian approachhas seemed less applicable outside the United States and WesternEurope.31Authors' personal communication with ROC representative,June-July 2002.

145

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

9/15

ContraCoercion February2004

1998, many ROCs (e.g., YUKOS, Sibneft, and TNK)faced bankruptcy and lacked a cash flow to servicetheir short-term secured bank debt (Tanguy 2002).32Because many of them acquired substantial foreigndebt, the Russian government's decision to devalue theruble made it even more expensive for the ROCs to re-pay these loans (RPI, September 1998,7). Over the firstnine months of 1999, for example, the indebtedness of5 major ROCs went up 54% (Kommersant,November23, 1999). As a result, they were unable to pay salariesand some of them (e.g., Sibneft) were forced either toshut down their operations for several months or toradically downsize their operations and decrease ex-penditures (RPI, October 1998, 17).33Moreover, due totheir reduced cash flow,combined with the lack of priorstrategic planning and domestic investment to boostproductive capacity, they could not immediately reapthe benefits of the ruble's devaluation by increasingproduction.34

Similarly, the 1998 financial crisis exposed the gov-ernment's susceptibility to fluctuations in the globalmarketplace because of its dependence on the oil sec-tor for budgetary revenue. Almost immediately, federalgovernment revenues and expenditures plunged in re-sponse to the 1998 crisis. According to the IMF (2000,60, 63), cash revenues dropped in the third quarter of1998 to just 7% of the GDP, from 10.5% of the GDPin the first half of 1998, and cash spending fell in thethird quarter to 11% of the GDP, from 16% of theGDP in the first half of 1998. As a result, according toSergei Shatalov, First Deputy Minister of Finance, whohad been a strong (but lonely) advocate of tax reformsince the mid-1990s, "The 1998 financial crisis createdthe collective realization that we needed to change the[current] system of securing revenue."35The August 1998 financial crisis also made itpainstakingly clear that they were dependent on oneanother not only for their economic recovery but alsoto insulate themselves from the effects of future crises,which required stable rules. For the ROCs, at a mini-mum "recovery" required investing in modernization,for which they also needed both greater predictabilityand more secure property rights.Prior to the 1998crisis,the ROCs' property rightswere threatened by frequenttax inspections that resulted in profit losses throughindiscriminate taxes and fees.36The 1998 crisis,further-more, exacerbated the fear among the ROCs that thegovernment might renationalize their assets becausemany of them accumulated huge tax arrears and facedbankruptcy.37

At a maximum, the ROCs' "recovery" required at-tracting Western partners in order to improve theirassets at home and expand their operations abroad,which in turn required increasing transparency (e.g.,disclosing information about profits and providing ac-curate information about profitabilityto shareholders)and establishing corporate governance. Specifically,the ROCs recognized that strategic partnerships withWestern companies would give them access to foreigncapital and technology, thereby enabling them to en-gage in the long-term strategic planning and domesticinvestment that were clearly so vital after the August1998 crisis.38At both ends of the spectrum, then, theROCs could not recover without obtaining formalguar-antees from the government that it would not arbitrar-ily expropriate their assets or the proceeds from theseassets through indiscriminate taxation.39 Tax legisla-tion, moreover, would both enhance predictability andrequire increased transparency, thus providing themwith the stability to invest in their assets at home andthe credibility to attract Western partners to expandtheir operations abroad."Recovery" for the Russian government required,at a minimum, budgetary stability. In order to regaintheir budgetary losses in the short term and to stabilizethe flow of tax revenue from the oil sector, the Russiangovernment needed to give the ROCs a greater incen-tive to pay their taxes voluntarily. As aforementioned,throughout the 1990s, the Russian government reliedheavily on taxing the oil sector to fill its coffers. Inaddition to exorbitant corporate income tax rates, oilproducers were subject to a fixed excise tax rate andstiff export tariffs.Yet, by August 1998, it became clearthat this strategy was leading to the ROCs' insolvencyand creating an unreliable revenue stream. The fixedexcise tax rate, for example, meant that oil producerspaid approximately 55 rubles per ton (or about $9.00)regardlessof the price of oil. Thus,when oil prices plum-meted in 1998, "manyof the companies [were driven]tothe verge of bankruptcy" (Samoylenko 1998,3) At thesame time, cumbersome bankruptcy procedures ham-pered the Russian government's ability to seize privateassets to induce tax compliance.40The government's "recovery" at a maximum re-quired expanding the tax base and increasing compli-ance overall so as to reduce the budget's dependenceon the oil sector for revenue. Structural reform aimedat promoting real growth across sectors thus becamea top priority for the government, and establishinga stable tax regime was a central component of this

32 Authors' personal communications with ROC representatives,op.cit.33Authors' personal communications with ROC representatives, op.cit.34Authors' personal communications with ROC representatives,op.cit.35Authors' personal communication, July 2002.36 Authors' personal communication with Tom Adshead, TroikaDi-alog, July 2002.37 Authors' personal communications with Stephen O'Sullivan,United FinancialGroup,July2002, and with representatives of ROCs,op. cit.

38 The desire for strategicpartnershipsdoes not mean that the ROCssought foreign direct investment or that they were willingto shareeq-uityin the Russian energy sector with Westerncompanies but, rather,they were willing to make Western companies minority shareholdersin order to gain access to foreign markets.39Authors' personal communications with representatives of ROCs,op. cit., and domestic andforeign oil and gas analysts,June-July2002.40Russia has introduced several versions of insolvency laws sinceindependence (i.e., 1992 insolvency law and the 1998 insolvency law),which has resulted in many ambiguities, making implementation anextremely difficult process. (For details, see OECD 1995). In 2002Putin vetoed the latest version (Pravda, August 7, 2002).

146

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

10/15

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

11/15

ContraCoercion February2004

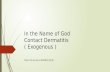

FIGURE1. Increase in DomesticInvestment/CapitalExpenditures, 1998-20016000

SurgutneftegazUTOil-- -TNK5000 - -x - - TatneftS- +. YUKOS--Rosneft--e - Bashneft-----Sibneft4000 -- -- Slavneft..---. SIDANCOr--'-- TotaloilcompaniesS 3000

2000

1000

. ;.._;--. _ _ .1998 1999 2000 2001YearSource:Troika ialog.

own company's intention to continue to reinvest inits domestic projects. Finally, the ROCs agreed to re-veal their profits through their implementation of inter-national accounting methods (i.e., GAAP standards)and corporate governance codes (RPI, October 2001).Overall, these incremental strategic moves assured theRussian government that the ROCs were serious aboutbringing their profits onshore and no longer hidingthem by investing offshore.The ROCs' overtures did not go unrequited. Severalkey actors within the Russian government simultane-ously made incremental strategic moves that were in-tended to convey its own commitment to reform. First,the Ministry of Energy and Fuel introduced several taxproposals in late 1998 to eliminate the oil excise taxand to introduce instead a variable tax on incremen-tal revenue in order to reduce the tax burden on theROCs and provide incentives for the ROCs to adoptWestern technologies and to establish alliances withforeign partners (RPI, September 1998, 27). Althoughthere were a few officials in the Ministry of Financereceptive to tax reform in the early to mid-1990s, suchas Shatalov, this ministrywas generally opposed to suchcuts after the crisis for fear that it would lead to furtherlosses to the federal budget (see, e.g., RPI, March 1998,39).49 Second, Yeltsin's dismissal of Prime MinisterKiriyenko, who had initiated accelerated bankruptcyproceedings against the ROCs in mid-1998, and his

replacement by Yevgeni Primakov in September con-veyed to the ROCs that the Russian government hadabandoned its attempts at coercion and was willing tonegotiate. Although initially he advocated a reversal ofRussia's neoliberal reforms, shortly after his appoint-ment Primakov met with representatives of the largestROCs to begin seeking a compromise (Kommersant,September 30, 1998, 4). Primakov's appointment alsoconveyed to the ROCs that the Yeltsin administrationwas committed to pursuing the formalization of the taxcode by working with the Duma on tax reform ratherthan reverting to setting arbitrarytax rates by executivedecree. While Kiriyenko and "the reformers" lacked amajority coalition in the Duma, Primakov was consid-ered to be acceptable to the large faction of Commu-nists in the Duma (Shleifer and Treisman 2000, 177).This was reassuring to the ROCs, both because it sig-naled the government's willingness to compromise andbecause they universally considered a formal tax code,which required the approval of the Duma, to offer morestability than tax reform by decree.50This commitmentwas reinforced in December 1998, when the Russiangovernment proposed a package of eight laws to theDuma, which linked tax rates to the profitabilityof oilwells, and then again in January1999,when PartI of theRussian Tax Code officially went into effect (Vasiliev2000). To further demonstrate its commitment to fis-cal reform and its willingness to compromise with boththe ROCs and the Duma, the Primakov governmentintroduced a reduction in the profits tax from 35% to30% (RFE/RL, November 17, 1998;Vasiliev 2000). Al-though the Duma had approved a similar reduction inJuly 1998 (RFE/RL, July 16, 1998), President Yeltsinvetoed the law (RFE/RL, July 20, 1998).The government's next set of incremental strategicmoves took place under Putin's leadership. First, atthe beginning of 2000 he established the Ministry ofEconomic Development and Trade to deal preciselywith the task of promoting long-term economic growth.This new ministry immediately began to dominate thedebates over tax reform inside the government and torepresent the government's position in private negoti-ations with the ROCs and public debates in the Duma.It thus replaced the Ministry of Finance, which hadspearheaded the government's previous approach totax reform (see, e.g., Samoylenko 1998, 2) and whichfinancial analysts and ROCs alike agree was fixated onfulfilling short-term budgetary requirements.51Then, at the end of 2000, Putin supported the forma-tion of a special "workinggroup" composed of govern-ment officials,Duma deputies, and the ROCs to discussthe remaining aspects of the tax code, especially thosethat were of special concern for the ROCs, such as thecorporate profits tax and the mineral tax.52 The Min-istryof Economic Development and Trade in these dis-cussions advocated dramatic cuts in tax rates as away tosimultaneously stimulate investment in long-term and49 According to Shatalov,he sought to push through tax reformin theearly 1990s, but he resigned in frustration because, prior to the 1998financial crisis, "the Yeltsin administration's was not committed toreal tax reform." Only after the Putin administration demonstratedits commitment to tax reform did Shatalov agree to return to thegovernment, at which time the Ministry of Finance also becamemore receptive to tax reform.Authors' personal communication withShatalov, op. cit.50 Authors' personal communication with Ustinov, op. cit.51Authors' personal communications with representatives of ROCs,op. cit., and with domestic and foreign financial analysts, op. cit.52Authors' personal communication with Shatalov, op. cit.

148

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

12/15

American Political Science Review Vol. 98, No. 1

new oil projects53and increase tax compliance acrosssectors.54By advocating a flat tax on corporate profitsof 24%, for example, the government was committingto a much lower share of the oil companies' profits inexchange for the full disclosure of their actual profits.In fact, the Russian TaxMinistry actually anticipated adecrease in tax collection in 2002 because of the newprofits tax (Pravda, June 12, 2001). Morevoer, the Min-istry of Economic Development and Trade, unlike theMinistry of Finance, supported the flat tax on personalincome and corporate profits tax because they believedthat it would eventually expand the government's taxbase by encouraging investment in other economic sec-tors (i.e., beyond the oil sector) and reducing the size ofthe illegal economy.55They were also behind the morerecent proposals to compensate companies "for lossesresulting from adjustment of transfer prices for taxpurposes"56and to establish a flat mineral tax pegged tothe world market price of oil. The latter, in particular,was deliberately designed to guarantee a more stablerevenue flow to both the ROCs and the governmentover the long term.57The formation of this group thusconveyed to the ROCs not only that the governmentremained committed to tax reform, but also that it re-mained committed to working with the Duma to enacttax legislation. At this time, the Russian governmentalso provided additional assurances to the ROCs-inboth public and private forums-that it would not makesignificant changes to the tax code for at least threeyears after it was adopted in 2001, which is consideredto be a fairly long period of time in Russia.58Finally, as each side became more secure withtheir reciprocal reassurances, their respective strate-gic moves became increasingly bold. Thus, in orderto reassure the ROCs that the Russian governmentwould cease to arbitrarily expropriate their profits andassets, Putin met with the Russian oligarchs in mid-2000 in Moscow, where he informed them privatelyand then announced publicly that "[he] would stay outof business, if [they] stayed out of politics" (see, e.g.,Feifer 2000).59The reaction of the ROCs was universalrelief because they viewed this public announcementas a credible commitment to respecting their propertyrights because Putin had effectively tied his hands byraising the costs of renationalizing their assets.60

CONTRACOERCION:ELITEBARGAINSANDINSTITUTIONALHANGEAs the new institutionalism moved from American tocomparative politics, the scholarly conception of in-stitutions as contractual agreements was transformedinto a conception of institutions as coercive or im-posed outcomes. Russia's ability to establish a viabletax code, however, demonstrates that this emphasis oncoercion, particularly in discussions of economic re-form processes, is inappropriate. This new tax code wasnot imposed by a strong central leader, mandated byinternational institutions, or the result of state captureby powerful economic interest groups, as both the gen-eral literature predicts and specialists on Russia oftenpresume. Rather, we argue that it is the product of amutually beneficial exchange between the two mostpowerful actors in Russia-the Russian governmentand the Russian oil companies (ROCs)-following anacute economic crisis.The explanation we put forth provides an opportu-nity to refine both the contractarian approach and theliterature on economic reform because it suggests bothan alternative mechanism whereby two equally power-ful actors can achieve mutual gains from cooperationand a set of conditions under which and an alternativemechanism whereby exogenous shocks induce institu-tional and economic policy change. The August 1998financial crisis provided the impetus for change in theform of a new tax code because it generated widelyshared perceptions among both the Russian govern-ment and the ROCs concerning the benefits of cooper-ation and the need for formal guarantees. These sharedperceptions, however, were contingent upon both setsof actors feeling equally vulnerable to the effects ofthe crisis (i.e., mutual vulnerability) and recognizingthat they depended on one another to recover fromthe crisis (i.e., interdependence). Shared perceptionsalone were also insufficient to bring about institutionalor economic policy change. Rather, the new tax coderequired that both sets of actors possessed commonknowledge, which was achieved through a series of in-cremental strategic moves.Our findings also have several implications for thefuture study of institutional creation and economic pol-icy change. First, they suggest that institutional changeis a gradual process with distributional consequences(gains as well as losses) for all the actors involved. Incontrast with the contractarian approach to institutionsfound in both comparative politics and internationalrelations, the recognition that there are mutual gainsfrom cooperation does not immediately generate newinstitutions and economic policies. Furthermore, the in-stitutional change and economic policies that do comeabout require all parties to the bargain to make consid-erable trade-offs. While both sides benefited from reli-able revenue streams and stable rules of the game, theyalso had to incur heavy losses. The ROCs paid for these

53 The previous tax system discouraged oil companies from investingin long-term and large new projects (authors' personal communi-cation with Yermakov, op. cit., and with representatives of ROCs,June-July 2002).54Authors' personal communication with Dvorkovich, op. cit.55Authors' personal communication with Dvorkovich, op. cit.,Reznikov, op. cit., and Vyugin, op. cit.56Authors' personal communication with Yermakov, op. cit.57Authors' personal communication with Dashevsky, op. cit.58 Authors' personal communication with Ustinov, op. cit. Instead,the government pledged to introduce only minor amendments to"work out the bugs out of the code" (authors' personal communica-tion with Ustinov, op. cit.).59Authors' personal communication with O'Sullivan, op. cit., andwith Adshead, op. cit.60Authors' personal communications with representatives of ROCs,September 2001 and June 2002. Since this time, Putin has publiclyreaffirmed the government's commitment not to renationalize assetsthat were privatized before 1998 on numerous occasions (see, e.g.,RFE/RL, 29 September 2003, RFE/RL, 22 September 2003).

149

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

13/15

Contra Coercion February2004benefits by agreeing to full disclosure and stricter gov-ernmental controls, which, despite the reduced profitstax, increased their overall tax burden. Similarly, byagreeing to the new tax code the Russian governmentforfeited its advantage vis-a-vis the ROCs-not onlycould it no longer raise tax rates arbitrarily,but it alsorisked a deficit in its budget revenue if the ROCs failedto comply with the new tax rates.Second, they demonstrate that neither a strongleader nor powerful economic interests can simply im-pose institutional creation or policy change. This chal-lenges not only the conventional wisdom concerningthe politics of economic reform in developing countriesbut also the two dominant (and contradictory) portray-als of the Russian state as either fully "captured" byeconomic interests or steered from above by PresidentVladimir Putin since his election in March 2000. More-over, it suggests that the existence of two equally pow-erful actors enhances rather than hinders prospects foreconomic reform-a notion that has found empiricalsupport beyond Russia (see, e.g., Arce 2003 and Kang2002).Finally, our findings belie the perception that Russiais "cursed" by its resource wealth (see, e.g., Rutland2001 and Starr 1998) and, instead, support the claimthat private ownership of natural resources fosters thedevelopment of institutions conducive to long-termeconomic growth (Weinthal and Jones Luong 2002).61If Russia's oil sector had been state-owned in August1998, the financial crisis would not have had the sameeffect on actors' perceptions and consequent behav-ior because these actors would not have felt the samedegree of vulnerability and interdependence followingthe financial crisis. The Russian government, for ex-ample, would have had several other options, such asconfiscating profits arbitrarily,increasing exports, andborrowing abroad against future revenue from theirresource wealth.62 The existence of private firms,how-ever, meant that seizing assets required complicatedand costly legal procedures. Similarly,the ROCs couldhave turned to the government to subsidize their re-covery through foreign loans rather than seeking tofinance it themselves. They would have neither beenin a position to pressure the government to establishformal guarantees against arbitrary expropriation oftheir assets nor felt the need for such an agreement.Thus, Russia's new tax code both demonstrates howtransition economies can move beyond the supposeddeadlock created by "earlywinners" and provides someconfirming evidence for the hypothesis that privati-zation to domestic actors offers a potential way forresource-rich countries to escape the so-called "re-source curse" because it forces governments to negoti-ate with these actors for revenue.

REFERENCESAitken, Brian. 2001. "Falling Tax Compliance and the Rise of theVirtual Budget in Russia."IMF staffpapers. Vol. 48.Alesina, Alberto, and Allan Drazen, 1991. "WhyAre StabilizationsDelayed?" American Economic Review 81 (5): 1170-88.Alexeev, Michael. 1999. "The Effect of Privatization and the Distri-bution of Wealth in Russia." Economics of Transition7 (2):449-65.Andersen, Arthur. 2002. Doing business in Russia. http://www.arthurandersen.ru.Arce, Moises. 2003. "The Sustainability of Economic Reform in aMost Likely Case: Peru."ComparativePolitics 35 (3): 335-54.Aslund, Anders. 2001. "Russia."Foreign Policy, July/August,20-25.Aslund, Anders. 2002. "How Russia Was Won." Moscow Times,21 November.Baldwin, David A., ed. 1993. Neorealism and neoliberalism:The con-temporarydebate. New York: Columbia University Press.Bates, Robert H. 1988. "Contra Contractarianism: Some Reflec-tions on the New Institutionalism." Politics and Society 16 (June-September): 387-401.Black, Bernard, Reinier Kraakman, and Anna Tarassova. 2000."Russian Privatization and Corporate Governance: What WentWrong?" Stanford Law Review 52: 1731-1808.Chaudhry,Kiren. 1993. "The Myths of the Market and the CommonHistory of Late Developers." Politics and Society 21 (3): 245-74.Colton, Timothy J.,and Michael McFaul. 2000."Reinventing Russia'sPartyof Power: 'Unity' and the 1999 Duma Election." Post-SovietAffairs 16 (3): 201-25.Drazen, Allan, and Vittorio Grilli. 1993. "The Benefit of Crises forEconomic Reforms."American Economic Review 83 (3): 598-607.Easter, Gerald. 2002. "Politics of Revenue Extraction in Post-Communist States: Poland and Russia Compared." Politics andSociety 30 (4): 599-627.Feifer, Gregory.2000."Presidentto Meet with 18Oligarchs."MoscowTimes,26 July.Fernandez, Raquel, and Dani Rodrik. 1994. "Resistance to Reform:Status Quo Bias." In Monetary and Fiscal Policy, ed. Persson andTabellini. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Firmin-Sellers, Kathryn. 1995. "The Politics of Property Rights."American Political Science Review 89 (4): 867-81.Goldman, Marshall I. 1999. "Russian Energy: A Blessing and aCurse."Journal of InternationalAffairs 53 (1): 73-84.Gustafson, Thane. 1999. Capitalism Russian-style. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.Haggard, Stephen, and Robert Kaufman, eds. 1992. The Politics ofEconomic Adjustment. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Haggard, Stephan, and Robert R. Kaufman. 1997. "The PoliticalEconomy of Democratic Transitions."ComparativePolitics29 (3):262-83.Hardin, Russell. 1982. Collective action. Baltimore: Johns HopkinsUniversity Press.Hellman, Joel. 1998. "Winners Take All: The Politics of PartialRe-form in Post-Communist Transitions." World Politics 50 (2): 203-34.Hellman, Joel, Geraint Jones,and Daniel Kaufman. September 2000.Seize the state, seize the day, state capture, corruption and influ-ence in transition economies.Policy Research WorkingPaper2444.

Washington, DC: World Bank.International Monetary Fund. 2000. Russian Federation: Selected is-sues. IMF Staff Country Report No.00/150. Washington,DC: IMEJervis, Robert. 1978. "Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma."World Politics 30 (2): 167-214.Johnson, Juliet. 1997. "Russia's Emerging Financial-IndustrialGroups."Post-SovietAffairs 13 (4): 333-65.Jones Luong, Pauline. 2000. "The Use and Abuse of Russia's EnergyResources: Implications for State-Societal Relations." In Buildingthe Russian state: Institutional crisis and the quest for democraticgovernance, ed. Valerie Sperling. Boulder, CO: Westview.Jones Luong, Pauline, and Erika Weinthal. 2001. "Prelude to theResource Curse: Explaining Energy Development Strategies inthe Soviet Successor States and Beyond." Comparative PoliticalStudies 34 (4): 367-99.Kahler,Miles. 1989. "International Financial Institutions andthe Pol-itics of Adjustment." In Fragilecoalitions: Thepolitics of economicadjustment,ed. Joan/Nelson. Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

61 Goldman (1999) argues precisely the opposite-i.e., that privati-zation has hampered reform efforts.62 These are the most common responses to "busts"among resource-rich countries in which the resource in question is state-owned (see,e.g., Karl 1997 and Ross 2001).

150

-

8/4/2019 Contra Coercion Russian Tax Reform, Exogenous Shocks, And Negotiated Institutional Change

14/15

American Political Science Review Vol. 98, No. 1Kang, David. 2002. Crony capitalism: Corruption and developmentin South Korea and the Philippines. Cambridge, UK/New York:Cambridge University Press.Karl, TerryLynn. 1997. Theparadox of plenty: Oil booms and petro-states.Berkeley: University of California Press.Kiewiet, D. Roderick, and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1991. The logic of

delegation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Knight, Jack. 1992. Institutions and social conflict. Cambridge Uni-versity Press.Knight, Jack. 1998. "Models, Interpretations, and Theories: Con-structing Explanations of Institutional Emergence and Change."In Explaining social institutions, ed. Jack Knight and Itai Sened.Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 95-120.Krasner Stephen. 1984. "Approaches to the State: Alternative Con-ception and Historical Dynamics." Comparative Politics 16 (2):223-46.Krueger Anne 0. 1993. Political economy of policy reform in devel-oping countries. Cambridge,MA: MIT Press.Levi, Margaret. 1988. Of rule and revenue. Berkeley: University ofCalifornia Press.Lloyd, John. 2000. "The Autumn of the Oligarchs."New York TimesMagazine 150 (October 8): 88-94.Maoz, Zeev, and Dan S. Felsenthal. 1987. "Self-Binding Commit-

ments, the Inducement of Trust,Social Choice, and the Theory ofInternational Cooperation."International Studies Quarterly31 (2):177-200.Mazalov, Ivan. 2001. Oil taxation changes. Moscow: Troika DialogResearch.McFaul, Michael. 1995. "State Power, Institutional Change, and thePolitics of Russian Privatization."World Politics 47 (January):210-43.Mitra,Pradeep K. 1994.Adjustmentin oil-exportingdeveloping coun-tries.New York: Cambridge University Press.Moe, Terry M. 1984. "The New Economics of Organization."American Journal of Political Science 28: 739-77.Nicholson, Martin. 2001. "Putin's Russia: Slowing the Pendulumwithout Stopping the Clock." InternationalAffairs 77 (4): 867-84.North, Douglass, and BarryWeingast.1989. "Constitutions and Com-mitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choicein Seventeenth-Century England." Journal of Economic History49 (4): 803-32.OECD. 1995. "A New Insolvency Law for Russia." http://www.oecd.org/pdf/M000015000/M00015641.pdf.OECD. 2000. OECD economic surveys: Russian Federation. Paris:OECD.OECD. 2001. The investment environment in the Russian Federation:Laws, policies, and issues. Paris:OECD.Olson, Mancur. 1965. Thelogic of collectiveaction. Public goods andthe theory of groups. Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press.Olson, Mancur. 1982. The rise and decline of nations. New Haven,CT:Yale University Press.Rabushka, Alvin. 2002. "The Flat Tax at Work in Russia." TheRussian Economy. Hoover Institution, Stanford University. http://www.russiaeconomy.org/comments/022102.html (February21).Reddaway, Peter, and Glinski, Dmitri. 2001. The tragedyof Russia'sreforms:MarketBolshevism against democracy. Washington, DC:U.S. Institute of Peace Press.Remington, Thomas. 2001. TheRussianparliament:Institutionalevo-lution in a transitional Regime, 1989-1999. New Haven, CT:YaleUniversity Press.Remmer, Karen. 1998. "The Politics of Neoliberal Economic Reformin South America, 1980-1994." Studies in Comparative Interna-tional Development 33 (2): 3-29.RFE/RL Russian Election Report. 2000. Number 5, 7 April.Robert, Cynthia, and Thomas Sherlock. 1999. "Bringingthe RussianState Back In: Explanations of the Derailed Transition to MarketEconomy." Comparative Politics 31 (4): 477-498.Rodrik, Dani. 1997. Has globalization gone toofar? Washington, DC:Institute for International Economics.Ross, Michael L. 2001. Timber booms and institutional breakdown inSoutheastAsia. Cambridge,UK/New York:Cambridge UniversityPress.Rossiyskaya Gazeta. 1998. 4 November, pp. 3, 7. ["Russia and theWorld,First-Hand: Russia Is Rich and Immense. So Why Are WeSo Poor?"].

Russian Economic Trends. 1998. http://www.blackwellpublishers.co.uk/ruet/ (December 8).Rutland, Peter. 2001. "Shifting Sands: Russia's Economic Develop-ment and its Relations with the West." Paper presented at theconference Russia and the West at the Millenium, organized bythe George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.Sachs, Jeffrey. 1994. "Life in the Economic Emergency Room."In The political economy of policy reform, ed. John Williamson.Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.Samoylenko, Vladimir A. 1998. "TaxReform in Russia: Yesterday,Today and in the Near Future." ITIC commentary. http://www.iticnet.org/publications/online/Samoylenko/RusTxRfm.htm(April).Schamis,Hector. 1999. "Distributional Coalitions and the Politics ofEconomic Reform in Latin America." World Politics 51 (January):236-68.Schelling, Thomas. 1960. The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.Shafer, Michael D. 1994. Winners and losers: How sectors shape thedevelopmental prospects of states. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UniversityPress.Shepsle, Kenneth A. 1986. "Institutional Equilibrium and Equilib-rium Institutions." In Political science: The science of politics, ed.