18 Climate-friendly development: analysing relationships between community, society and government on sustainable technology projects. Cai J. Heath University of Birmingham* Ladakh Studies 32 • January 2015 • 18 - 35 Abstract This study highlights the conditions required for successful integration of sustainable technologies with poverty reduction strategies in rural locations. This study focuses on ongoing sustainable development programmes in Ladakh to qualitatively study the main challenges for sustainable and climate-sensitive approaches to development. Ladakh, in the Indian Himalayas, is a key site to understand the implementation of sustainable and socially-equitable solutions to threats posed by climate change. Data was gathered through interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups with community members. The respondents included governmental, non-governmental and private actors as well as beneficiaries of sustainable technology-based development projects. This study finds that approaches to development in Ladakh are not currently integrating climate change adaptation with renewable energy and watershed development programmes. This is causing discontent among rural inhabitants who feel that their increasing vulnerability to climate change is not being addressed. In a severe climatic environment such as Ladakh, it is important that solutions are tailored to local context. If local government and non-governmental actors continue to develop networks and partnership opportunities, Ladakh can serve as a model for adaptive multi-stakeholder approaches to climate-friendly poverty reduction in the Himalayan region and around the world. Key words: Renewable energy, sustainable development, watershed management * Field research in Ladakh was undertaken as part of a postgraduate degree course at the University of Birmingham in July and August 2010. The author is currently affiliated with the School of Public Health at Imperial College, London

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

18

Climate-friendly development analysing relationships between community society and government on sustainable technology projects

Cai J HeathUniversity of Birmingham

Ladakh Studies 32 bull January 2015 bull 18 - 35

AbstractThis study highlights the conditions required for successful integration of sustainable technologies with poverty reduction strategies in rural locations This study focuses on ongoing sustainable development programmes in Ladakh to qualitatively study the main challenges for sustainable and climate-sensitive approaches to development

Ladakh in the Indian Himalayas is a key site to understand the implementation of sustainable and socially-equitable solutions to threats posed by climate change Data was gathered through interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups with community members The respondents included governmental non-governmental and private actors as well as beneficiaries of sustainable technology-based development projects

This study finds that approaches to development in Ladakh are not currently integrating climate change adaptation with renewable energy and watershed development programmes This is causing discontent among rural inhabitants who feel that their increasing vulnerability to climate change is not being addressed In a severe climatic environment such as Ladakh it is important that solutions are tailored to local context If local government and non-governmental actors continue to develop networks and partnership opportunities Ladakh can serve as a model for adaptive multi-stakeholder approaches to climate-friendly poverty reduction in the Himalayan region and around the world

Key words Renewable energy sustainable development watershed management

Field research in Ladakh was undertaken as part of a postgraduate degree course at the University of Birmingham in July and August 2010 The author is currently affiliated with the School of Public Health at Imperial College London

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

19Climate-friendly development

The inhabitants of the high-altitude cold deserts in the Himalaya and Karakoram mountain ranges tackle harsh living conditions and are among the most vulnerable groups to climate change (Parry et al 2007)

Rural communities have limited access to natural resources and often rely on biomass as an energy resource which can further degrade their fragile and isolated environment (Rai 2005) The Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau have shown significant susceptibility to climate change (Parry et al 2007) and even small changes in temperature over the coming decades will have a severe impact on agriculture and water supply through effects on glacial melting (ibid) In addition traditional pastoralism has reduced in the last few decades though nomadism and seasonal livestock movement persists in some regions and led to attempts to convert arid high-altitude landscapes for large-scale agriculture (Sharma 2010)

Though rainfall is very low at only ten centimetres per year on average flooding events and cloudbursts do happen infrequently (Hobley 2012) When they do occur the region is particularly vulnerable as its terrain is comprised of loose deposits of rock and silt that can lead to mudslides during heavy rainfall and damage structures and destroy arable land (Daultrey and Gergan 2011) Thus sustainable climate adaptation strategies notably watershed development and sustainable approaches that minimise environmental impact are becoming key concerns for Himalayan communities

Ladakh is situated between the Karakoram and Himalayan mountain ranges and is divided into Leh and Kargil districts The population of Leh district is 147104 and the largest urban area is Leh which has a population of around 93961 (INC 2011) The rural communities in Ladakh are largely focussed on subsistence production and usually limited to a single crop per year of barley and wheat (Van den Akker and Takpa 2003) Occasionally peas potatoes and other vegetables are grown contingent to adequate water supply The average plot of land per household is small due to the limited amount of arable land and tends to be less than half a hectare (Daultrey and Gergan 2011) This means that sheep and goat rearing is often a major source of livelihood and provide meat and milk during the winter months (Thapa 2010)

In recent years the impacts of climate change have become increasingly visible in Ladakh Snowfall and rainfall patterns have become more erratic as evidenced partly by the flash-floods along the Indus river in August 2010 which killed at least 233 people and injured 424 (LAHDC 2011) Many small glaciers and high snow fields have shrunk drastically in the last 50 years which has greatly reduced water runoff to rivers and streams (Hobley 2012) Some communities

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

20 Climate-friendly development

that lack snow and glacial water reserves have been forced to relocate and are part of a growing number of lsquoclimate refugeesrsquo (Richeux 2012)

Despite the bitter cold during winter Ladakh has a great resource that is largely untapped sunshine The region benefits from more than 300 days of sunshine a year which can be harnessed through renewable energy technologies and passive solar construction techniques to meet basic household needs and support economic activities (Van den Akker and Takpa 2003) The unique climate in Ladakh combined with its glacial topography has also led to the innovation of artificial glaciation to increase water supply for agriculture and boost micro-hydro generation potential

Climate-friendly developmentConsidering Ladakhrsquos geography and climate this paper aims to provide case studies of ongoing sustainable development programmes and qualitatively study the main challenges to the success of sustainable climate-sensitive approaches to development In this section I provide an overview of key sustainable techniques in current use in Leh based on my field study and desk-based research

Sustainable Technologies amp TechniquesSustainable technology is a form of design that specifically aims to use renewable resources in an environmentally-friendly manner they also tend to be more energy-efficient than non-sustainable alternatives (Vergragt 2006) In comparison appropriate technology is a parallel and overlapping concept that focuses strongly on the appropriateness of a technology to a particular context without necessarily having the same concerns for sustainability or environmental protection the most appropriate technology in a given situation may well not be the most sustainable one (Akabue 2000) Sustainable technology is a highly flexible term it is described variably as appropriate and sustainable technology (AST) eco-design green engineering and environmentally sustainable design amongst others Examples of sustainable technologies are renewable energy technologies such as wind turbines and solar photo-voltaic (PV) panels as well as passive technologies such as solar cookers artificial glaciers and passive solar housing design

The main sustainable technologies and techniques currently implemented in Ladakh are passive solar construction techniques solar photo-voltaic generation artificial glaciation techniques and household-level appliances such as solar cookers solar water heaters and solar lanterns Micro-hydro power installations are also in place in Ladakh however they have been affected by reduced flow rates in rivers caused by reduction in glacial mass (Rai 2005) While the Ladakh

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

21Climate-friendly development

Renewable Energy Development Agency (LREDA) has more recently actively promoted micro-hydro power generation none of the actors interviewed for this study were actively pursuing this approach at the time of writing and this study does not expand further on this technology Wind power is under trial in a few locations by local government agencies However reduction in wind strength during summer months is a major challenge to the introduction of this technology (Kumar 2010)

The three key focuses for development projects in Leh are

Passive Solar TechniquesPassive solar design takes advantage of solar radiation during the winter months to heat the inside of buildings including houses greenhouses to cultivate plants and animal sheds The main design considerations are a south-facing orientation and large insulated windows that enable enough solar radiation to be collected during the day to keep rooms warm at night too

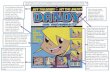

Figure 1 Example of a lsquodirect gainrsquo passive solar installation incorporating local lsquoShinstakrsquo carving techniques

Photograph taken by the author July 2010

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

22 Climate-friendly development

The four key approaches to effective passive solar construction are1 Collection of maximal solar radiation during the day2 Efficient storage of heat during the day3 Release of the stored heat into the room during the night4 Insulation of the entire building to retain as much heat as possible (Kjorven 2006)

These techniques can be implemented on new buildings but tend to be utilised for lsquoretro-fittingrsquo existing homes due to financial constraints The techniques are relatively low-cost for the benefits gained and use locally abundant materials such as wool for insulation Passive solar design is highly flexible and always improves indoor temperatures For a capital cost of between INR 10000 to 40000 (USD 185 to 740) depending on the capacity and conversion potential of the room under renovation fuel use can be reduced by 60 percent At the same time indoor temperatures will remain above 5 degrees Celsius at night compared to minus 25 degrees Celsius outside (Stauffer 2010) Without the introduction of these techniques house temperatures can be as low as minus 10 degrees Celsius during the winter months which has significant health impacts like hypothermia

Passive solar projects are conducive to increased economic productivity during the winter months They are often connected with income-generating projects such as handicrafts and wool transformation that are up to 50 percent more fruitful in the brighter and warmer conditions provided by the solar design (Martinot 2005)

Artificial Glaciation TechniquesWhile not a renewable energy source as such the innovative and sustainable technique of artificial glaciation has been developed in Ladakh to harness a renewable resource water This technique provides a significantly longer period of spring-time glacial melt which can lead to higher crop yields

Most villages in Ladakh rely on water from glacial melt and snow fields above their village Water is crucial for irrigating crops and for domestic use In the cold winter months a lot of water is wasted as no crops are grown and taps are left running to prevent freezing This innovative water collection system initially a localised technique for water collection on a very small scale has been used to prevent water wastage This technique has been pioneered by the NGO Leh Nutrition Project over the past two decades and has been refined to increase the amount of water harvested

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

23Climate-friendly development

An artificial glacier is formed by a network of water channels and dams along the upper slope of a valley During the coldest months of the year streams are diverted into a shady valley or to the north side of mountains where the water flow slows down and eventually freezes Retaining walls are built to further slow down the water and facilitate a stepped lsquoartificial glacierrsquo using locally available resources like stone and labour (Sultana 2009)

The artificial glaciers are at lower altitudes than natural glaciers and melt at different times in the spring to ensure a continuous supply of water for irrigation Artificial glaciers require about 50000 tonnes of water and last for 2-3 months The techniques are being refined to achieve a greater thickness of ice across nine sites in Ladakh (Johansson 2012)

The main benefit of this approach is an increased income source for villagers who can grow more crops each year including water-intensive lsquocash cropsrsquo like potatoes and peas It would not be possible to grow without increased water supply though traditional crops are still grown on first rotation for subsistence use On an environmental level the glaciers recharge underground aquifers and conserve soil moisture which makes the process even more sustainable

Figure 2 An artificial glacier in late winter Nang Ladakh Photograph by Chewang Norphel (LNP) 2007

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

24

Artificial glaciers can also assist social cohesion as water is a critical resource and communities have been known to have major disputes over irrigation rights The increased springtime water-flow from these glaciers reduces the likelihood of such disputes as well as climate-based migration (Richeux 2012)

Solar Photovoltaic GenerationThe photovoltaic (PV) process converts solar energy directly into electricity PV technology in the form of solar panels has no moving parts which makes them a low maintenance method to generate energy in areas like Ladakh that receive around 300 days of sunshine

Batteries are used to store electricity collected by the panels during daylight hours The batteries tend to be the weakest component of solar PV applications as they have a maximum lifetime of around five years and further reduced if the battery is not maintained well (International Energy Agency 2008) Batteries need topping up with water and the surface of the panels require frequent cleaning to maximise radiation reception Solar PV electricity generation is very flexible and can be scaled from a small 5W roof panel for household lighting to a 100kW array to power a large village

Climate-friendly development

Figure 3 A small lsquosolar home systemrsquo atop a roof in the Nubra district of Ladakh Photograph by the author July 2010

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

25

In Ladakh solar power is an optimum source of renewable energy as it receives more days of sunshine than almost anywhere else on the planet (Van den Akker and Takpa 2003) The prime conditions for solar PV production are long cold clear sunny days which suits Ladakhi winters very well

Sustainable technology organisations in LadakhFollowing desk-based research and consultation with local NGOs during the early stages of the research it was decided to focus on six development actors who work directly on sustainable technology projects in Ladakh This section briefly summarises the history and objectives of each organisation Key informants from the staff members of these organisations were identified and interviewed

GERES (Groupe Eacutenergies Renouvelables Environnement et Solidariteacutes)GERES1 is a French NGO that works in India Afghanistan Cambodia and numerous west and north African countries The Indian branch of GERES is based in Ladakh and has been working since 1986 to support the implementation of eco-friendly technology projects that promote income generation activities GERES also works to support and train local organisations including local government to increase sustainable technology diffusion in the region (Stauffer 2010) GERESrsquo main project undertaken at the time of the research was to implement passive solar construction projects and accompanying income-generating activities in 1000 households across 100 Ladakhi villages which was completed in December 2012 (Richeux 2013)

LEDeG (Ladakh Ecological Development Group)Founded in 1983 LEDeG2 works to promote and disseminate renewable energy technologies such as micro-hydro power solar cookers and solar PV panels as well as providing education about conservation and the environment LEDeGrsquos most recent project has been to construct a 100kW solar PV plant and run an integrated livelihoods project in Durbuk block of Leh district as well as numerous small micro-hydro installation in remote communities It also acts as a local resource organisation for passive solar design notably the lsquoTrombe Wallrsquo a technique that glazes the south-facing walls of a building and vets the collected heat through the building

1 See for more details of their work in India httpwwwgereseuengeres-india 2 See for more details of their work httpwwwledegorg

Climate-friendly development

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

26

LEHO (Ladakh Environment and Health Organisation)LEHO is a Ladakhi organisation that specialises in ecological architecture to improve health standards The NGO has been active since 1991 and focuses on passive solar housing to reduce indoor smoke from biomass heating as well as solar greenhouses and solar lambing sheds to increase farm productivity LEHO specialises in the social aspects of development and have a training programme for local communities to monetise wool processing and other handicrafts that run alongside its passive solar housing work

LNP (Leh Nutrition Project)The Leh Nutrition Project was set-up by Save the Children Fund (UK) in 1978 and focuses on initiatives to increase agricultural production LNPrsquos domestic and community-led solar greenhouse project has been replicated and rolled out by the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) Leh to 2750 households LNP has also developed the concept of artificial glaciation that has increased agricultural productivity in nine valleys where the project has been implemented The organisation is a knowledge resource in the region for solar passive agricultural applications

SECMOL (Studentsrsquo Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh)SECMOL3 is a youth education centre that works to raise awareness of environmental and rural energy issues amongst young people SECMOLrsquos educational centre relies entirely on a selection of sustainable energy techniques such as solar PV panels solar pumps solar cookers and passive solar construction The centre was constructed in 1988 and demonstrates the ability of sustainable techniques to support a community as the centre houses around 60 people from local villages each year who are given tuition on energy efficiency recycling and general educational support SECMOL provides expertise to other local NGOs on insulation techniques as well as the management and storage of solar PV energy

LREDA (Ladakh Renewable Energy Development Agency)LREDA4 is the local government agency based within LAHDC Leh that develops renewable energy projects in the region both with and outside the electricity grid network LREDA has been working to provide basic energy services to remote communities in Ladakh since its formation in 1997 Their projects are a combination of installation of small solar PV panel for

3 See for more details httpwwwsecmolorg 4 See for more details httpwwwladakhenergyorg

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

27

household electricity and the distribution of solar-powered lanterns and solar cookers LREDA does have large-scale renewable projects that support whole communities and supply between 20 to 100kW of power LREDA is supported by the Government of Indiarsquos Ministry for New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) and was recently awarded INR 473 billion Rupees (USD 836 million) for the development of solar thermal (for both water and building heating) micro-hydro and solar PV projects (Kumar 2010)

Besides these key actors there are several NGOs that are indirectly involved in sustainable development projects These include World Wide Fund for Nature who educate communities on reducing biomass dependency to reduce environmental stress Rural Development amp You (RDY) a local watershed development organisation that constructs water reservoirs to improve river flow for optimal micro-hydro power and artificial glaciation and Save the Children who advocate improved access to energy services to improve child health and better access to education

MethodologyThe methodology was divided into two parts First 22 qualitative interviews were carried out with key commentators and stakeholders in Ladakhrsquos sustainable technology-based development sector Second two participatory focus group discussions with local beneficiaries of sustainable development projects were conducted with a total of 16 villagers A key area for analysis was the link between the community organisations and project management approaches Data were triangulated to gain an accurate understanding of the situation given the constraints of time and resources available for the study Being a Western researcher may have had an impact on the responses generated I aimed to mitigate this through the use of a structured interview process and by working with local translators and NGOs

I Semi-structured interviewsThe cross-section of staff included project officers directors and engineers of NGOs local government agencies and private companies based in Leh The range of actors was chosen to access different views on sustainable technology projects The insights gained from these interviews provided an overview of the strategy challenges and key goals for sustainable technology projects in Ladakh The interview schedules were semi-structured to allow for detailed discussions on project conceptualisation and management of sustainable technology initiatives

II Semi-structured interviews and focus group discussionsA set of semi-structured interview questions and ranking exercises were used

Climate-friendly development

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

28

to assess whether livelihoods were sustainable and the key needs of community members in Umla village Umla has implemented passive solar housing and artificial glaciation projects over the past five years with GERES RDY and LEHO The village was also a part of LAHDC Lehrsquos solar lantern programme In the context of this study this approach was deemed the most practical way of gathering qualitative data The village of Umla was identified as a key case study for project implementation by a variety of actors including governmental and non-governmental projects over the previous five years The village has a population of around 150 people and is located at 3600 metres above mean sea level which is typical for villages around Leh town The process was informed by participatory literature and aimed to have a participant-oriented approach to collecting data while also being quick and flexible (Chambers and Conway 1992) This approach is generally seen as the middle path in terms of cost-effective lsquohit and runrsquo data collection techniques and lengthy academic research (Bhandari 2003)

The ranking exercises and the key commentator interviews were based on the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) as it offers a people-centred dynamic and sustainability focused outlook and also fits well with the concept of sustainable technology-based development and vulnerability (DFID 1999) The SLF focuses on five key assets to reduce vulnerability human capital natural capital financial capital social capital and physical capital (see Figure 1) These assets gain meaning when analysed within structural and process-related contexts as being key factors in the facilitation of successful and sustainable poverty reduction projects (Kollmair and Gamper 2002)

Climate-friendly development

Figure 1 The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (DFID 1999)

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

29Climate-friendly development

While the SLF does not necessarily have the ability to capture every facet and turn it into relevant action it is a useful tool to investigate the structures and processes that affect human livelihoods (Scoones 2009) The framework places the poor in a context of vulnerability where they have access to a limited number of livelihood assets These assets are viewed and controlled through specific overarching organisational social institutional and environmental structures and processes (Song et al 2006) This context governs the livelihood strategies available to achieve beneficial livelihood outcomes The SLF is a competent method to create a checklist of key issues and identify linkages between them There is also a central focus on the structures and processes that interact with other factors in the framework It should be noted that like all models and frameworks the SLF is a simplification and cannot fully demonstrate the complexity of livelihoods (DFID 1999) Some recent versions of the SLF focus on different capital inputs but the system selected was adopted as it was judged as being able to capture community and environment-based factors

For the focus group sessions a review of the local context and programming along with the SLF were used to create a series of interactive questions and ranking exercises that were posed to groups formed on the basis of gender and age to reduce social bias A local translator helped facilitate the interviews and exercises Two groups were formed of young people (aged 18-25) with women in one group (9 participants) and men over 25 year in a separate group (7 participants) These groups were formed to maintain peer grouping and the numbers were limited by the size of the community hall at Umla A key element of this process was that the workshops and meetings were relatively informal flexible and within the community (Bhandari 2003)

ResultsThe interviews with key commentators in the Ladakh sustainable technologies sector and focus groups with villagers uncovered a perceived lack of communication and need assessment between local government and rural communities This disconnect has led the local government to focus on renewable energy schemes with lighting as the main energy service outcome rather than heating which focus group participants strongly indicated was their priority [13 out of 16 respondents ranked heating projects as the most important sustainable technology intervention] A local government engineer at LREDA commented ldquoEfficient operation and maintenance are key to project success communities are trained by our contractorsrdquo but noted that a few of their expensive solar panel electrification projects in rural locations had gone offline due to a lack of battery top-ups This is a relatively basic task given to local villagers but they lacked the resources to conduct regular follow-ups with

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

30

communities Some villagers seemed disillusioned with government actors and perceive them to be detached from their day-to-day rural lives [9 out of 16 villagers ranked the local government as the least engaged in their community of the current development partners] In the focus group discussions a majority of villagers identified natural and human factors as being most important for the development of energy services while financial and social aspects were ranked least important This result potentially indicates that climatic factors are more important to villagers than financial or social factors While intriguing it should be noted that the village was already receiving subsidised assistance from NGOs in the development of passive solar buildings and an artificial glacier It is therefore possible that Umla lacks financial concerns faced by more remote and unassisted communities

Ladakhi NGOs admit that some of their projects fail but are approaching evaluation of these failures in an adaptive and participative manner A notable example is the recent development of a grassroots network of sustainable technology organisations and community groups with the tentative involvement of the local government

Non-governmental actors are implementing small-scale often innovative approaches to climate change adaptation and poverty reduction in Ladakh but their programmes are struggling to scale-up due to funding constraints and lack of government support The development of artificial glaciers by the staff at LNP is a key example of how a small team with limited resources can make a large impact by using resources at hand creatively and sustainably to improve rural livelihoods

Respondents in the focus groups noted that often there is a lack of ownership for projects initiated by the government and international NGOs who implemented development projects without working closely with the local community [10 of the 16 respondents noted that projects went into disrepair due to lack of ownership after government and international development partners left the community] More ownership was felt for the work of Leh-based Ladakhi NGOs One villager noted ldquoSchools and health centres built by the government donrsquot get looked after and often get vandalised in some of the larger villages in the area As a small village with limited resources we have to make do with what wersquore givenrdquo This attitude seems to stem from a perceived lack of government involvement at the grass-roots level An example of this detachment in terms of sustainable technology projects is that LREDA does not carry out detailed need assessments but rely on basic data on income and village population provided by the hill council as they do not have the staff capacity to perform energy surveys in each village

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

31Climate-friendly development

Based on visits to LNPrsquos artificial glaciation projects in two villages besides Umla and interviews with local community leaders and NGO staff it seems that these communities are heavily reliant on a consistent water supply as they are situated in valleys that do not have natural glaciers Snow-melt from the artificial glaciers increases water supply to these communities in spring with river levels dropping off significantly in the late summer In Umla focus group respondents rated natural capital (water and other natural resources like wood rocks and plant matter) as the most important contributing factor to the general well-being and development of the community [13 of 16 respondents rated it the most important factor] The focus groups rated human (education and skills) and physical (technology irrigation and roads) as being the second and third most important capital respectively One senior member of the village commented ldquoSnowfall has decreased a lot in the last fifty years The summer is now very short and we could only grow one crop till we developed our artificial glacierrdquo With the artificial glacier in place the community harvests two crops each year and grows valuable herbs and potatoes that were not possible earlier due to lack of water and time

Interestingly villagers in both groupings did not rate financial aspects as being important for development and ranked it last in the SLFrsquos five forms of capital However villagers admitted that it was initially a challenge to take advantage of the new opportunities One villager noted ldquoThe community struggled to gather enough men and women to work the fields with the new water our irrigated land expanded significantly Earlier many young people had left for Leh or joined the army as they offered better economic opportunities Now we have managed to convince enough of them to return We are now growing so many potatoes that we are regularly taking them for sale in Leh The results are plain to seerdquo

Rural communities seem to mistrust those from the urban centre of Leh The villagers who participated in the focus group discussions felt disconnected not only from the local government in Leh but also from the townrsquos way of life This influenced their decision-making during negotiations of development projects for their community [this was shown by the perceived lack of ownership for government projects and 12 out of 16 felt that the local government did not represent them personally] The results of the ranking exercise showed that villagers rated heating as the energy service that is most important to them followed by cooking (water and fuel) and then lighting this is despite the local governmentrsquos focus on providing solar lanterns rather than heating This result suggests a degree of disengagement between need and the local governmentrsquos programme focus especially since it was reported during group discussions and interviews that the lanterns had mostly stopped working Thus despite the

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

32

villagersrsquo lack of access to lighting they still regarded heating as more important It should be noted that the government solar lantern programme was easier and significantly cheaper to implement initiallymdash effectively distributing lanterns onlymdashas compared to a programme focused on improving home insulation The availability of funds from central government for the roll out of the project was another reason for it being implemented However the focus groups were consistent in stating that the solar lanterns did not last and was one of the reasons that contributed to their perception of the local government being disengaged from their needs

There are signs that local organisations and government staff are starting to band together to increase their efficiency and quality of project delivery A network of NGOs has been initiated by GERES based on the concept of lsquoresource organisationsrsquo and lsquoproximity organisationsrsquo Resource NGOs are more experienced and skilled at technology implementation while proximity NGOs are technically less experienced but have a stronger relationship with local communities The project administrator for GERES who co-ordinates the network commented ldquoThe grass-roots network is not just for local NGOs but for community leaders and local government members too The network aims to increase awareness of sustainable solutions to increase livelihoods and by involving members of LAHDC we hope to further the case for improved energy efficiency in homes We hope they will soon set the standard with public buildings The network also provides a useful new forum for training and information sharing with the LAHDCrdquo

ConclusionThe challenge of reducing poverty through sustainable technology interventions in Ladakh is varied There is hope that strong partnerships of public and private actors can come together to implement intelligent unified responses to climate change and poverty reduction The technologies are not part of the major challenges faced by the projects The solution must bring together governments communities and NGOs in an integrated and multi-stakeholder approach In Ladakh there are signs of progress with regards to the newly-formed grass-roots network and innovative highly sustainable and appropriate responses to poverty reduction such as passive solar design and artificial glaciation However these schemes are still reaching a limited number of communities and require government support to make an impact across the region

Through the lens of the sustainable livelihoods framework the responses of different actors suggest that the local government is not communicating programme goals clearly at the grassroots level and some key livelihoods needs

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

33Climate-friendly development

are not being met This situation has led to some discontent amongst villagers who feel that government actors are oblivious to their increasing vulnerability to climate change In an extreme climatic environment such as Ladakh it is important that solutions are tailored to local context This is especially relevant to a country like India which has a broad range of climates and sometimes makes national-level strategies inappropriate at the local level Local government actors could engage more with the expertise of local NGOs through the new network of renewable energy organisations Vice versa the local government has a responsibility for villages across the district and are thus spread very thinly on the ground which possibly contributes to negative perceptions among villagers NGOs tend to be more hands-on and are thus perceived to be more caring in the villages where they work but have no presence in other areas A middle-ground where approaches to development in each community are looked at holistically and government and NGO actors combine their strengths for more effective programme implementation This approach is somewhat evidenced in Umla where NGOs and government are working on a set of complementary sustainable technology projects However more can be done to harmonise activities and secure the backing of the local populace for a unified lsquoend goalrsquo for the community

While approaches to poverty reduction in Ladakh are not without problems the progress made shows that a group of dedicated organisations communities and individuals coupled with innovative techniques can create a strategy for successfully merging poverty reduction and climate change adaptation If local government actors are further incorporated into the growing network of sustainable development organisations in the region then Ladakh can be a flagship for adaptive multi-stakeholder approaches to eco-friendly poverty reduction around the world

References

Akubue A 2000 Appropriate Technology for Socioeconomic Development in Third World Countries The Journal of Technology Studies XXIV pages 33-43

Bhandari B 2003 Participatory Rural Appraisal Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) Kanagawa Japan

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

34

Chambers R and Conway G 1992 Sustainable rural livelihoods practical concepts for the 21st century Institute of Development Studies (IDS) Discussion Paper 296 Brighton Available at httpopendocsidsacukopendocsbitstreamhandle123456789775Dp296pdf

Daultrey S and Gergan R 2011 Living with Change adaptation and innovation in Ladakh Our Planet Climate Adaptation Available at httpwwwourplanetcomclimate-adaptationDaultrey_Gerganpdf

DFID 1999 Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets DFID UK Available at httpwwweldisorgvfileupload1document0901section2pdf

Hobley DEJ et al 2012 Reconstruction of a major storm event from its geomorphic signature The Ladakh floods 6 August 2010 Geology v 40 p 483-486 doi101130G329351 Available at httpwwwgeosedacukhomessmuddHobley_geology2012pdf

International Energy Agency 2008 Rural Energy Services for Developing Countries In Support of the Millennium Development Goals Paris Available at httpiea-pvpsorgindexphpid=158ampeID=dam_frontend_pushampdocID=203

INC 2011 Indian National Census The Office of the Registrar General amp Census Commissioner Government of India New Delhi Data available at httpwwwcensusindiagovin(S(2pta2z45uttgjh55ssvdt245))pcaSearchDetailsaspxId=3985

Johansson EL 2012 The Melting Himalayas Examples of Water Harvesting Techniques Seminar series 237 Lund University Sweden Available at httpluplubluseluurdownloadfunc=downloadFileamprecordOId=2760100ampfileOId=2760103

Kjorven O 2006 Energising the MDGs going beyond business as usual to address energy access sustainability and security New York United Nations Development Programme

Kollmair M and Gamper S 2002 The Sustainable Livelihood Approach Input Paper for the Integrated Training Course of NCCR North-South Aeschiried Switzerland

Kumar V 2010 Government of India approves Rs 473 Cr renewable energy project for Ladakh Ground Report New Delhi Available at httpgroundreportcomgovernment-of-india-approves-rs-473-cr-renewable-energy-project-for-ladakh

LAHDC 2011 Disaster Management Plan Leh District Deputy Commissionerrsquos Office Leh available at httpwwwlehnicin

Martinot E (ed) 2005 Renewables 2005 Global Status Report Worldwatch Institute Washington DC

Ministry for New and Renewable Energies 2009 Renewable Energy Plan for Ladakh Renewable Energy Magazine Vol 3(2) New Delhi

Parry ML et al (Eds) 2007 Climate Change 2007 Impacts Adaptation and Vulnerability Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Asia) Cambridge University Press Cambridge UK

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

35

Rai SC (ed) 2005 Glaciers Glacier Retreat and the Subsequent Impacts in Nepal India and China WWF (Nepal) Kathmandu Available at httpassetswwforgukdownloadshimalayaglaciersreport2005pdf_ga=17446901012659150301414592300

Richeux C 2013 GERES Passive Solar Architecture Fondation Ensemble Factsheet March 2013 Available at httpwwwfondationensembleorgfichestechFT_Geres_habitat_GBpdf

Richeux C 2012 GERES The Artificial Glacier or the Water Issue in Ladakh Fondation Ensemble Factsheet June 2012 Available at httpwwwfondationensembleorgfichestechFT_Geres_Glaciers_GBpdf

Scoones I 2009 Livelihoods Perspectives and Rural Development Journal of Peasant Studies Vol 36 (1) January 2009 Available athttpwwwessentialcellbiologycomjournalspdfpapersFJPS_36_1_2009pdf

Sharma JK 2010 Calamity Cloudburst in Choglamsar Ladakh The Times of India Economics Section 9th August 2010 Available at httparticleseconomictimesindiatimescom2010-08-09news28416779_1_global-warming-water-bodies-zanskar

Song HN et al 2006 Capacity Building on Sustainable Livelihoods Analysis and Participatory Rural Appraisal Working Paper NSH1 EU Project MANGROVE INCO-CT-2005-003697 Hanoi Vietnam NACA STREAM (Support to Regional Aquatic Resources Management)

Stauffer V (ed) 2010 2009 Ashden Awards Case Study GERES amp Ashden Awards joint paper May 2010 Paris Available at httpwwwashdenorgfilespdfsfinalist_2009GERES_case_study_2009pdf

Sultana R (ed) 2009 The Effective Utilization of Solar Energy Leh Nutrition Project Leh Thapa P 2010 Training of Self Help Groups on Wool Transformation using Renewable

Energy Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association (BORDA) Research Paper

Van den Akker J and Takpa J 2003 Solar PV on the Top of the World Renewable Energy World

Vergragt PJ 2006 How Technology Could Contribute to a Sustainable World GTI Paper Series - 8 The Tellus Institute Boston Available at httpwwwgtinitiativeorgdocumentsPDFFINALS8Technologypdf

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

19Climate-friendly development

The inhabitants of the high-altitude cold deserts in the Himalaya and Karakoram mountain ranges tackle harsh living conditions and are among the most vulnerable groups to climate change (Parry et al 2007)

Rural communities have limited access to natural resources and often rely on biomass as an energy resource which can further degrade their fragile and isolated environment (Rai 2005) The Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau have shown significant susceptibility to climate change (Parry et al 2007) and even small changes in temperature over the coming decades will have a severe impact on agriculture and water supply through effects on glacial melting (ibid) In addition traditional pastoralism has reduced in the last few decades though nomadism and seasonal livestock movement persists in some regions and led to attempts to convert arid high-altitude landscapes for large-scale agriculture (Sharma 2010)

Though rainfall is very low at only ten centimetres per year on average flooding events and cloudbursts do happen infrequently (Hobley 2012) When they do occur the region is particularly vulnerable as its terrain is comprised of loose deposits of rock and silt that can lead to mudslides during heavy rainfall and damage structures and destroy arable land (Daultrey and Gergan 2011) Thus sustainable climate adaptation strategies notably watershed development and sustainable approaches that minimise environmental impact are becoming key concerns for Himalayan communities

Ladakh is situated between the Karakoram and Himalayan mountain ranges and is divided into Leh and Kargil districts The population of Leh district is 147104 and the largest urban area is Leh which has a population of around 93961 (INC 2011) The rural communities in Ladakh are largely focussed on subsistence production and usually limited to a single crop per year of barley and wheat (Van den Akker and Takpa 2003) Occasionally peas potatoes and other vegetables are grown contingent to adequate water supply The average plot of land per household is small due to the limited amount of arable land and tends to be less than half a hectare (Daultrey and Gergan 2011) This means that sheep and goat rearing is often a major source of livelihood and provide meat and milk during the winter months (Thapa 2010)

In recent years the impacts of climate change have become increasingly visible in Ladakh Snowfall and rainfall patterns have become more erratic as evidenced partly by the flash-floods along the Indus river in August 2010 which killed at least 233 people and injured 424 (LAHDC 2011) Many small glaciers and high snow fields have shrunk drastically in the last 50 years which has greatly reduced water runoff to rivers and streams (Hobley 2012) Some communities

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

20 Climate-friendly development

that lack snow and glacial water reserves have been forced to relocate and are part of a growing number of lsquoclimate refugeesrsquo (Richeux 2012)

Despite the bitter cold during winter Ladakh has a great resource that is largely untapped sunshine The region benefits from more than 300 days of sunshine a year which can be harnessed through renewable energy technologies and passive solar construction techniques to meet basic household needs and support economic activities (Van den Akker and Takpa 2003) The unique climate in Ladakh combined with its glacial topography has also led to the innovation of artificial glaciation to increase water supply for agriculture and boost micro-hydro generation potential

Climate-friendly developmentConsidering Ladakhrsquos geography and climate this paper aims to provide case studies of ongoing sustainable development programmes and qualitatively study the main challenges to the success of sustainable climate-sensitive approaches to development In this section I provide an overview of key sustainable techniques in current use in Leh based on my field study and desk-based research

Sustainable Technologies amp TechniquesSustainable technology is a form of design that specifically aims to use renewable resources in an environmentally-friendly manner they also tend to be more energy-efficient than non-sustainable alternatives (Vergragt 2006) In comparison appropriate technology is a parallel and overlapping concept that focuses strongly on the appropriateness of a technology to a particular context without necessarily having the same concerns for sustainability or environmental protection the most appropriate technology in a given situation may well not be the most sustainable one (Akabue 2000) Sustainable technology is a highly flexible term it is described variably as appropriate and sustainable technology (AST) eco-design green engineering and environmentally sustainable design amongst others Examples of sustainable technologies are renewable energy technologies such as wind turbines and solar photo-voltaic (PV) panels as well as passive technologies such as solar cookers artificial glaciers and passive solar housing design

The main sustainable technologies and techniques currently implemented in Ladakh are passive solar construction techniques solar photo-voltaic generation artificial glaciation techniques and household-level appliances such as solar cookers solar water heaters and solar lanterns Micro-hydro power installations are also in place in Ladakh however they have been affected by reduced flow rates in rivers caused by reduction in glacial mass (Rai 2005) While the Ladakh

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

21Climate-friendly development

Renewable Energy Development Agency (LREDA) has more recently actively promoted micro-hydro power generation none of the actors interviewed for this study were actively pursuing this approach at the time of writing and this study does not expand further on this technology Wind power is under trial in a few locations by local government agencies However reduction in wind strength during summer months is a major challenge to the introduction of this technology (Kumar 2010)

The three key focuses for development projects in Leh are

Passive Solar TechniquesPassive solar design takes advantage of solar radiation during the winter months to heat the inside of buildings including houses greenhouses to cultivate plants and animal sheds The main design considerations are a south-facing orientation and large insulated windows that enable enough solar radiation to be collected during the day to keep rooms warm at night too

Figure 1 Example of a lsquodirect gainrsquo passive solar installation incorporating local lsquoShinstakrsquo carving techniques

Photograph taken by the author July 2010

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

22 Climate-friendly development

The four key approaches to effective passive solar construction are1 Collection of maximal solar radiation during the day2 Efficient storage of heat during the day3 Release of the stored heat into the room during the night4 Insulation of the entire building to retain as much heat as possible (Kjorven 2006)

These techniques can be implemented on new buildings but tend to be utilised for lsquoretro-fittingrsquo existing homes due to financial constraints The techniques are relatively low-cost for the benefits gained and use locally abundant materials such as wool for insulation Passive solar design is highly flexible and always improves indoor temperatures For a capital cost of between INR 10000 to 40000 (USD 185 to 740) depending on the capacity and conversion potential of the room under renovation fuel use can be reduced by 60 percent At the same time indoor temperatures will remain above 5 degrees Celsius at night compared to minus 25 degrees Celsius outside (Stauffer 2010) Without the introduction of these techniques house temperatures can be as low as minus 10 degrees Celsius during the winter months which has significant health impacts like hypothermia

Passive solar projects are conducive to increased economic productivity during the winter months They are often connected with income-generating projects such as handicrafts and wool transformation that are up to 50 percent more fruitful in the brighter and warmer conditions provided by the solar design (Martinot 2005)

Artificial Glaciation TechniquesWhile not a renewable energy source as such the innovative and sustainable technique of artificial glaciation has been developed in Ladakh to harness a renewable resource water This technique provides a significantly longer period of spring-time glacial melt which can lead to higher crop yields

Most villages in Ladakh rely on water from glacial melt and snow fields above their village Water is crucial for irrigating crops and for domestic use In the cold winter months a lot of water is wasted as no crops are grown and taps are left running to prevent freezing This innovative water collection system initially a localised technique for water collection on a very small scale has been used to prevent water wastage This technique has been pioneered by the NGO Leh Nutrition Project over the past two decades and has been refined to increase the amount of water harvested

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

23Climate-friendly development

An artificial glacier is formed by a network of water channels and dams along the upper slope of a valley During the coldest months of the year streams are diverted into a shady valley or to the north side of mountains where the water flow slows down and eventually freezes Retaining walls are built to further slow down the water and facilitate a stepped lsquoartificial glacierrsquo using locally available resources like stone and labour (Sultana 2009)

The artificial glaciers are at lower altitudes than natural glaciers and melt at different times in the spring to ensure a continuous supply of water for irrigation Artificial glaciers require about 50000 tonnes of water and last for 2-3 months The techniques are being refined to achieve a greater thickness of ice across nine sites in Ladakh (Johansson 2012)

The main benefit of this approach is an increased income source for villagers who can grow more crops each year including water-intensive lsquocash cropsrsquo like potatoes and peas It would not be possible to grow without increased water supply though traditional crops are still grown on first rotation for subsistence use On an environmental level the glaciers recharge underground aquifers and conserve soil moisture which makes the process even more sustainable

Figure 2 An artificial glacier in late winter Nang Ladakh Photograph by Chewang Norphel (LNP) 2007

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

24

Artificial glaciers can also assist social cohesion as water is a critical resource and communities have been known to have major disputes over irrigation rights The increased springtime water-flow from these glaciers reduces the likelihood of such disputes as well as climate-based migration (Richeux 2012)

Solar Photovoltaic GenerationThe photovoltaic (PV) process converts solar energy directly into electricity PV technology in the form of solar panels has no moving parts which makes them a low maintenance method to generate energy in areas like Ladakh that receive around 300 days of sunshine

Batteries are used to store electricity collected by the panels during daylight hours The batteries tend to be the weakest component of solar PV applications as they have a maximum lifetime of around five years and further reduced if the battery is not maintained well (International Energy Agency 2008) Batteries need topping up with water and the surface of the panels require frequent cleaning to maximise radiation reception Solar PV electricity generation is very flexible and can be scaled from a small 5W roof panel for household lighting to a 100kW array to power a large village

Climate-friendly development

Figure 3 A small lsquosolar home systemrsquo atop a roof in the Nubra district of Ladakh Photograph by the author July 2010

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

25

In Ladakh solar power is an optimum source of renewable energy as it receives more days of sunshine than almost anywhere else on the planet (Van den Akker and Takpa 2003) The prime conditions for solar PV production are long cold clear sunny days which suits Ladakhi winters very well

Sustainable technology organisations in LadakhFollowing desk-based research and consultation with local NGOs during the early stages of the research it was decided to focus on six development actors who work directly on sustainable technology projects in Ladakh This section briefly summarises the history and objectives of each organisation Key informants from the staff members of these organisations were identified and interviewed

GERES (Groupe Eacutenergies Renouvelables Environnement et Solidariteacutes)GERES1 is a French NGO that works in India Afghanistan Cambodia and numerous west and north African countries The Indian branch of GERES is based in Ladakh and has been working since 1986 to support the implementation of eco-friendly technology projects that promote income generation activities GERES also works to support and train local organisations including local government to increase sustainable technology diffusion in the region (Stauffer 2010) GERESrsquo main project undertaken at the time of the research was to implement passive solar construction projects and accompanying income-generating activities in 1000 households across 100 Ladakhi villages which was completed in December 2012 (Richeux 2013)

LEDeG (Ladakh Ecological Development Group)Founded in 1983 LEDeG2 works to promote and disseminate renewable energy technologies such as micro-hydro power solar cookers and solar PV panels as well as providing education about conservation and the environment LEDeGrsquos most recent project has been to construct a 100kW solar PV plant and run an integrated livelihoods project in Durbuk block of Leh district as well as numerous small micro-hydro installation in remote communities It also acts as a local resource organisation for passive solar design notably the lsquoTrombe Wallrsquo a technique that glazes the south-facing walls of a building and vets the collected heat through the building

1 See for more details of their work in India httpwwwgereseuengeres-india 2 See for more details of their work httpwwwledegorg

Climate-friendly development

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

26

LEHO (Ladakh Environment and Health Organisation)LEHO is a Ladakhi organisation that specialises in ecological architecture to improve health standards The NGO has been active since 1991 and focuses on passive solar housing to reduce indoor smoke from biomass heating as well as solar greenhouses and solar lambing sheds to increase farm productivity LEHO specialises in the social aspects of development and have a training programme for local communities to monetise wool processing and other handicrafts that run alongside its passive solar housing work

LNP (Leh Nutrition Project)The Leh Nutrition Project was set-up by Save the Children Fund (UK) in 1978 and focuses on initiatives to increase agricultural production LNPrsquos domestic and community-led solar greenhouse project has been replicated and rolled out by the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) Leh to 2750 households LNP has also developed the concept of artificial glaciation that has increased agricultural productivity in nine valleys where the project has been implemented The organisation is a knowledge resource in the region for solar passive agricultural applications

SECMOL (Studentsrsquo Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh)SECMOL3 is a youth education centre that works to raise awareness of environmental and rural energy issues amongst young people SECMOLrsquos educational centre relies entirely on a selection of sustainable energy techniques such as solar PV panels solar pumps solar cookers and passive solar construction The centre was constructed in 1988 and demonstrates the ability of sustainable techniques to support a community as the centre houses around 60 people from local villages each year who are given tuition on energy efficiency recycling and general educational support SECMOL provides expertise to other local NGOs on insulation techniques as well as the management and storage of solar PV energy

LREDA (Ladakh Renewable Energy Development Agency)LREDA4 is the local government agency based within LAHDC Leh that develops renewable energy projects in the region both with and outside the electricity grid network LREDA has been working to provide basic energy services to remote communities in Ladakh since its formation in 1997 Their projects are a combination of installation of small solar PV panel for

3 See for more details httpwwwsecmolorg 4 See for more details httpwwwladakhenergyorg

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

27

household electricity and the distribution of solar-powered lanterns and solar cookers LREDA does have large-scale renewable projects that support whole communities and supply between 20 to 100kW of power LREDA is supported by the Government of Indiarsquos Ministry for New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) and was recently awarded INR 473 billion Rupees (USD 836 million) for the development of solar thermal (for both water and building heating) micro-hydro and solar PV projects (Kumar 2010)

Besides these key actors there are several NGOs that are indirectly involved in sustainable development projects These include World Wide Fund for Nature who educate communities on reducing biomass dependency to reduce environmental stress Rural Development amp You (RDY) a local watershed development organisation that constructs water reservoirs to improve river flow for optimal micro-hydro power and artificial glaciation and Save the Children who advocate improved access to energy services to improve child health and better access to education

MethodologyThe methodology was divided into two parts First 22 qualitative interviews were carried out with key commentators and stakeholders in Ladakhrsquos sustainable technology-based development sector Second two participatory focus group discussions with local beneficiaries of sustainable development projects were conducted with a total of 16 villagers A key area for analysis was the link between the community organisations and project management approaches Data were triangulated to gain an accurate understanding of the situation given the constraints of time and resources available for the study Being a Western researcher may have had an impact on the responses generated I aimed to mitigate this through the use of a structured interview process and by working with local translators and NGOs

I Semi-structured interviewsThe cross-section of staff included project officers directors and engineers of NGOs local government agencies and private companies based in Leh The range of actors was chosen to access different views on sustainable technology projects The insights gained from these interviews provided an overview of the strategy challenges and key goals for sustainable technology projects in Ladakh The interview schedules were semi-structured to allow for detailed discussions on project conceptualisation and management of sustainable technology initiatives

II Semi-structured interviews and focus group discussionsA set of semi-structured interview questions and ranking exercises were used

Climate-friendly development

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

28

to assess whether livelihoods were sustainable and the key needs of community members in Umla village Umla has implemented passive solar housing and artificial glaciation projects over the past five years with GERES RDY and LEHO The village was also a part of LAHDC Lehrsquos solar lantern programme In the context of this study this approach was deemed the most practical way of gathering qualitative data The village of Umla was identified as a key case study for project implementation by a variety of actors including governmental and non-governmental projects over the previous five years The village has a population of around 150 people and is located at 3600 metres above mean sea level which is typical for villages around Leh town The process was informed by participatory literature and aimed to have a participant-oriented approach to collecting data while also being quick and flexible (Chambers and Conway 1992) This approach is generally seen as the middle path in terms of cost-effective lsquohit and runrsquo data collection techniques and lengthy academic research (Bhandari 2003)

The ranking exercises and the key commentator interviews were based on the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) as it offers a people-centred dynamic and sustainability focused outlook and also fits well with the concept of sustainable technology-based development and vulnerability (DFID 1999) The SLF focuses on five key assets to reduce vulnerability human capital natural capital financial capital social capital and physical capital (see Figure 1) These assets gain meaning when analysed within structural and process-related contexts as being key factors in the facilitation of successful and sustainable poverty reduction projects (Kollmair and Gamper 2002)

Climate-friendly development

Figure 1 The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (DFID 1999)

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

29Climate-friendly development

While the SLF does not necessarily have the ability to capture every facet and turn it into relevant action it is a useful tool to investigate the structures and processes that affect human livelihoods (Scoones 2009) The framework places the poor in a context of vulnerability where they have access to a limited number of livelihood assets These assets are viewed and controlled through specific overarching organisational social institutional and environmental structures and processes (Song et al 2006) This context governs the livelihood strategies available to achieve beneficial livelihood outcomes The SLF is a competent method to create a checklist of key issues and identify linkages between them There is also a central focus on the structures and processes that interact with other factors in the framework It should be noted that like all models and frameworks the SLF is a simplification and cannot fully demonstrate the complexity of livelihoods (DFID 1999) Some recent versions of the SLF focus on different capital inputs but the system selected was adopted as it was judged as being able to capture community and environment-based factors

For the focus group sessions a review of the local context and programming along with the SLF were used to create a series of interactive questions and ranking exercises that were posed to groups formed on the basis of gender and age to reduce social bias A local translator helped facilitate the interviews and exercises Two groups were formed of young people (aged 18-25) with women in one group (9 participants) and men over 25 year in a separate group (7 participants) These groups were formed to maintain peer grouping and the numbers were limited by the size of the community hall at Umla A key element of this process was that the workshops and meetings were relatively informal flexible and within the community (Bhandari 2003)

ResultsThe interviews with key commentators in the Ladakh sustainable technologies sector and focus groups with villagers uncovered a perceived lack of communication and need assessment between local government and rural communities This disconnect has led the local government to focus on renewable energy schemes with lighting as the main energy service outcome rather than heating which focus group participants strongly indicated was their priority [13 out of 16 respondents ranked heating projects as the most important sustainable technology intervention] A local government engineer at LREDA commented ldquoEfficient operation and maintenance are key to project success communities are trained by our contractorsrdquo but noted that a few of their expensive solar panel electrification projects in rural locations had gone offline due to a lack of battery top-ups This is a relatively basic task given to local villagers but they lacked the resources to conduct regular follow-ups with

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

30

communities Some villagers seemed disillusioned with government actors and perceive them to be detached from their day-to-day rural lives [9 out of 16 villagers ranked the local government as the least engaged in their community of the current development partners] In the focus group discussions a majority of villagers identified natural and human factors as being most important for the development of energy services while financial and social aspects were ranked least important This result potentially indicates that climatic factors are more important to villagers than financial or social factors While intriguing it should be noted that the village was already receiving subsidised assistance from NGOs in the development of passive solar buildings and an artificial glacier It is therefore possible that Umla lacks financial concerns faced by more remote and unassisted communities

Ladakhi NGOs admit that some of their projects fail but are approaching evaluation of these failures in an adaptive and participative manner A notable example is the recent development of a grassroots network of sustainable technology organisations and community groups with the tentative involvement of the local government

Non-governmental actors are implementing small-scale often innovative approaches to climate change adaptation and poverty reduction in Ladakh but their programmes are struggling to scale-up due to funding constraints and lack of government support The development of artificial glaciers by the staff at LNP is a key example of how a small team with limited resources can make a large impact by using resources at hand creatively and sustainably to improve rural livelihoods

Respondents in the focus groups noted that often there is a lack of ownership for projects initiated by the government and international NGOs who implemented development projects without working closely with the local community [10 of the 16 respondents noted that projects went into disrepair due to lack of ownership after government and international development partners left the community] More ownership was felt for the work of Leh-based Ladakhi NGOs One villager noted ldquoSchools and health centres built by the government donrsquot get looked after and often get vandalised in some of the larger villages in the area As a small village with limited resources we have to make do with what wersquore givenrdquo This attitude seems to stem from a perceived lack of government involvement at the grass-roots level An example of this detachment in terms of sustainable technology projects is that LREDA does not carry out detailed need assessments but rely on basic data on income and village population provided by the hill council as they do not have the staff capacity to perform energy surveys in each village

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

31Climate-friendly development

Based on visits to LNPrsquos artificial glaciation projects in two villages besides Umla and interviews with local community leaders and NGO staff it seems that these communities are heavily reliant on a consistent water supply as they are situated in valleys that do not have natural glaciers Snow-melt from the artificial glaciers increases water supply to these communities in spring with river levels dropping off significantly in the late summer In Umla focus group respondents rated natural capital (water and other natural resources like wood rocks and plant matter) as the most important contributing factor to the general well-being and development of the community [13 of 16 respondents rated it the most important factor] The focus groups rated human (education and skills) and physical (technology irrigation and roads) as being the second and third most important capital respectively One senior member of the village commented ldquoSnowfall has decreased a lot in the last fifty years The summer is now very short and we could only grow one crop till we developed our artificial glacierrdquo With the artificial glacier in place the community harvests two crops each year and grows valuable herbs and potatoes that were not possible earlier due to lack of water and time

Interestingly villagers in both groupings did not rate financial aspects as being important for development and ranked it last in the SLFrsquos five forms of capital However villagers admitted that it was initially a challenge to take advantage of the new opportunities One villager noted ldquoThe community struggled to gather enough men and women to work the fields with the new water our irrigated land expanded significantly Earlier many young people had left for Leh or joined the army as they offered better economic opportunities Now we have managed to convince enough of them to return We are now growing so many potatoes that we are regularly taking them for sale in Leh The results are plain to seerdquo

Rural communities seem to mistrust those from the urban centre of Leh The villagers who participated in the focus group discussions felt disconnected not only from the local government in Leh but also from the townrsquos way of life This influenced their decision-making during negotiations of development projects for their community [this was shown by the perceived lack of ownership for government projects and 12 out of 16 felt that the local government did not represent them personally] The results of the ranking exercise showed that villagers rated heating as the energy service that is most important to them followed by cooking (water and fuel) and then lighting this is despite the local governmentrsquos focus on providing solar lanterns rather than heating This result suggests a degree of disengagement between need and the local governmentrsquos programme focus especially since it was reported during group discussions and interviews that the lanterns had mostly stopped working Thus despite the

ARTICLES Ladakh Studies 32

32

villagersrsquo lack of access to lighting they still regarded heating as more important It should be noted that the government solar lantern programme was easier and significantly cheaper to implement initiallymdash effectively distributing lanterns onlymdashas compared to a programme focused on improving home insulation The availability of funds from central government for the roll out of the project was another reason for it being implemented However the focus groups were consistent in stating that the solar lanterns did not last and was one of the reasons that contributed to their perception of the local government being disengaged from their needs

There are signs that local organisations and government staff are starting to band together to increase their efficiency and quality of project delivery A network of NGOs has been initiated by GERES based on the concept of lsquoresource organisationsrsquo and lsquoproximity organisationsrsquo Resource NGOs are more experienced and skilled at technology implementation while proximity NGOs are technically less experienced but have a stronger relationship with local communities The project administrator for GERES who co-ordinates the network commented ldquoThe grass-roots network is not just for local NGOs but for community leaders and local government members too The network aims to increase awareness of sustainable solutions to increase livelihoods and by involving members of LAHDC we hope to further the case for improved energy efficiency in homes We hope they will soon set the standard with public buildings The network also provides a useful new forum for training and information sharing with the LAHDCrdquo

ConclusionThe challenge of reducing poverty through sustainable technology interventions in Ladakh is varied There is hope that strong partnerships of public and private actors can come together to implement intelligent unified responses to climate change and poverty reduction The technologies are not part of the major challenges faced by the projects The solution must bring together governments communities and NGOs in an integrated and multi-stakeholder approach In Ladakh there are signs of progress with regards to the newly-formed grass-roots network and innovative highly sustainable and appropriate responses to poverty reduction such as passive solar design and artificial glaciation However these schemes are still reaching a limited number of communities and require government support to make an impact across the region

Through the lens of the sustainable livelihoods framework the responses of different actors suggest that the local government is not communicating programme goals clearly at the grassroots level and some key livelihoods needs

Climate-friendly development

Ladakh Studies 32 ARTICLES

33Climate-friendly development

are not being met This situation has led to some discontent amongst villagers who feel that government actors are oblivious to their increasing vulnerability to climate change In an extreme climatic environment such as Ladakh it is important that solutions are tailored to local context This is especially relevant to a country like India which has a broad range of climates and sometimes makes national-level strategies inappropriate at the local level Local government actors could engage more with the expertise of local NGOs through the new network of renewable energy organisations Vice versa the local government has a responsibility for villages across the district and are thus spread very thinly on the ground which possibly contributes to negative perceptions among villagers NGOs tend to be more hands-on and are thus perceived to be more caring in the villages where they work but have no presence in other areas A middle-ground where approaches to development in each community are looked at holistically and government and NGO actors combine their strengths for more effective programme implementation This approach is somewhat evidenced in Umla where NGOs and government are working on a set of complementary sustainable technology projects However more can be done to harmonise activities and secure the backing of the local populace for a unified lsquoend goalrsquo for the community