CAS LX 502 14a. Discourse Representation Theory 10.9

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

CAS LX 502

14a. DiscourseRepresentation Theory

10.9

Meaning in discourse

• The formal stuff we have concerned ourselves with so far has primarily been concerned with evaluation of the truth conditions of sentences.

• In connected discourse, there is more going on, we need to take the discourse context into account.

For example

x[delegate(x) arrived(x)]

• ‘A delegate arrived.’

[x[[delegate(x) arrived(x)]]]‘It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive.’

• A delegate arrived. She registered.

• #It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive. She registered.

Updating the context

• Somehow A delegate arrived has updated the discourse context to provide an individual referent that can later be referred to by the pronoun She.

• It is not the case that every delegate failed to arrive does not update the context in the same way. It does not introduce a referent.

• Indefinite noun phrases like a delegate can introduce discourse referents.

Lifespan of a referent

• Pati bought an iPodj. Hei brings itj everywhere.• An iPod introduces a discourse referent that the

pronoun it can later refer to.

• #Pat didn’t buy an iPodj. He likes itj though.• If introduced in a negative clause, any discourse

referent there might have been is not available later.

Discourse Representation Theory

• DRT is a formal system to model the progression of meanings and referents in discourse.

• It is a system that keeps track of what referents are introduced and what can refer back to them.

• In the previous case, the negated sentence is the limit of the “reach” of the discourse referent introduced by an iPod. Negation blocks outside reference.

• It is not the case that [Pat bought an iPod].

Donkey science

• DRT is a response to the fairly famous problem with “donkey anaphora” of the following sort:

• If a farmeri owns a donkeyj, hei pets itj.

• It turns out that trying to write the truth conditions for this without the idea of introducing discourse referents is basically impossible.

Problems pre-DRT

• If you steal, you go to jail.

• Steal(you) go-to-jail(you).

• Joan owns a Ferrari.x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)]

• If Joan owns a Ferrari, she is rich.x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] rich(Joan)

Problems pre-DRT

• If Joan owns a Ferrari, she is rich.x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] rich(Joan)

• If Joan owns a Ferrari, she drives it.x[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ?

• No, that won’t work—x is unbound. Let’s bind it.x[[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ]?

• Well, but what does that mean? That’s not right.

Problems pre-DRT

• If Joan owns a Ferrari, she drives it.x[[Ferrari(x) owns(Joan, x)] drive(Joan, x) ]?• “Every Ferrari that Joan owns, she drives”

• That’s more or less right, but how did we get that meaning? Why does a Ferrari sometimes seem like it needs to be interpreted like every Ferrari?

• What is the compositional meaning of a Ferrari?

Discourse Representation Structures

• A DRS represents the discourse by listing the individuals in the “universe” of the DRS and properties known about them.

• Any subsequent sentence will be evaluated against this discourse background, updating the discourse context.

• This is true if there is an x that has those properties.

x

delegate(x)arrived(x)

Discourse Representation Structures

• A delegate arrived.

• She registered.

• Pronouns introduce a condition like y=? (meaning: search for a suitable accessible referent).

• When uttering the sentences in sequence, the second sentence must be merged with the first to yield a new DRS.

x

delegate(x)arrived(x)

registered(y)y=?

x y

delegate(x)arrived(x)

registered(y)y=x

Complex DRSes

• When constructing a DRS of a negative sentence, a subordinate DRS must be constructed.

• A delegate didn’t arrive

• A sentence of the form if S1 then S2 also requires a subordinate DRS.

• If Joan arrived, Bill arrived.

x

delegate(x)arrived(x)

arrived(y)

x y

Joan(x)Bill(y)

arrived(x)

Complex DRSes

• Proper names always introduce referents into the universe of the highest DRS.

• Indefinites like a delegate introduce referents into the DRS containing them.

• If Joan arrived, she met a delegate.

y z

delegate(z)met(y,z)

y=x

x

Joan(x)

arrived(x)

Complex DRSes

• If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall.

y z

delegate(z)met(y,z)

y=x

x

Joan(x)

arrived(x)w

tall(w)male(w)

w=?

Complex DRSes

• If Joan arrived, she met a delegate. He was tall.

• We can’t assign w to the delegate (referent z).

• The reason is that z is “hidden from view”—it is not accessible to the top-level DRS.

• What referents are accessible are governed by accessibility rules.

y z

delegate(z)met(y,z)

y=x

x w

Joan(x)

tall(w)male(w)

w=?

arrived(x)

Accessibility• If Joan arrived, she met a

delegate. He was tall.

• Suitable referents for an instruction like w=? are any referents in a universe that is either left or out. But never in or right.

• Out but not in:• y and z are not accessible from

the larger DRS. But x and w are accessible from the consequent sub-DRS.

y z

delegate(z)met(y,z)

y=x

x w

Joan(x)

tall(w)male(w)

w=?

arrived(x)

in

out

Accessibility• If a delegate arrived, he was happy.• If he was happy, a delegate arrived.

• Suitable referents for an instruction like w=? are any referents in a universe that is either left or out. But never in or right.

• Left but not right:• x is accessible from the consequent

DRS, but y is not accessible from the antecedent DRS.

y

happy(y)y=x

x

delegate(x) arrived(x)

right

left

y

delegate(y)arrived(y)

x

happy(x) x=?

Sue bought a car. It is fast.

If a boy is hungry, he eats.

If a boy is tired, he doesn’t play.

Pat didn’t buy a textbook.

• We’ve been sort of overlooking the fact that a sentence like Pat didn’t buy a textbook is actually ambiguous.

• It could mean that Pat bought no textbooks. This is basically what our DRSes predict.

• It could also mean that there is a textbook Pat failed to buy.

Unusually wide scope

• A phrase like a textbook is a quantifier, and so we expect that it could undergo QR.

• Assuming that negation is also a quantifier that can undergo QR (we didn’t treat this in our fragment), we expect the normal interaction between two quantifiers:

• A textbook > Not• There is a textbook such that Pat didn’t buy it.

• Not > A textbook• It is not the case that there is a textbook that Pat bought.

Unusually wide scope

• However, QR is usually limited to its own S:

• A fish said [S that Loren likes every book].

• A > every• There is a fish x such that x said that for every

book y, Loren likes y.

• *Every > A• For every book y, there is a fish x such that x said

that for every book y, Loren likes y.

Unusually wide scope

• Tracy drinks tea [S if every student calls].• If > Every

• If, for every student x, x calls, then Tracy drinks tea.

• *Every > If• For every student x, if x calls, then Tracy drinks tea.

• Pat didn’t say [S that Tracy bought every textbook].• Not > Every• *Every > Not

Unusually wide scope

• Every fish said [S that Loren likes a book].

• Tracy drinks tea [S if a student calls].

• With indefinite quantifiers like a book and a student, it seems to be possible to interpret them with widest scope, even when QR can’t normally provide widest scope—and it usually feels like it has a meaning like “a certain.”

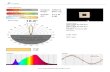

Tracy drinks tea if a student calls

• A DRS for the if > a student interpretation would look like this.• If there is a student that

calls, Tracy drinks tea.

• How would we get the other reading?• There is a certain student

such that if s/he calls, Tracy drinks tea.

drinks-tea(x)

x

Tracy(x)

y

student(y) calls(y)

Tracy drinks tea if a student calls

• Essentially what seems to happen is that the indefinite can be treated as a name.

• Making it a name means that it is placed in the universe of the highest DRS.

• This is a specific indefinite. drinks-tea(x)

x y

Tracy(x)student(y)

calls(y)

Every

• Every delegate arrived.

• Our translation of this was:x[delegate(x) arrived(x)]

• That is, being a delegate implies having arrived.

• We can write this asa DRS using the normalrule for writingconditionals. arrived(x)

x

delegate(x)

• The natural interpretation of the sentence on the left is something like: Being a cat implies being constantly on the move. (Generic interpretation).

on-the-move(x)

x

cat(x)

• The second sentence is incompatible with the first on that interpretation, though.

y z

heard-of(y, z)y = speaker

z = ?

on-the-move(x)x

cat(x) on-the-move(x)

y z

heard-of(y, z)y = speaker

z = ?

x

cat(x)

• What makes this “funny” is that we could also write this DRS using a specific indefinite, which can then be referred to using him.

x

cat(x)on-the-move(x)

y z

heard-of(y, z)y = speaker

z = ?

x y z

cat(x)on-the-move(x)heard-of(y, z)y = speaker

z = x

More specific indefinites

• “Last year, I handed in a script, and the studio didn't change one word.

…And the word they didn't change was on page 87.”• (Steve Martin,

hosting the Oscars)

DRT

• Discourse Representation Theory is a system to account for how we track referents through a discourse—how they are introduced, when they can serve as antecedents for pronouns in later sentences.

• The Discourse Representation Structure is a picture of the discourse environment at a given point, updated with each further utterance by merging the information in the new utterance with the information in the discourse environment.

Extra credit (due 4/27)

• 1. Do Saeed, ch. 10, problem 9.• 2. Follow the same instructions for the above problem

with the following two mini-discourses:• Every student took an exami. Iti was 4 pages long.

• If a student writes a paperi, iti is finished at 4am.

• 3. Explain why the following two mini-discourses sound wrong by drawing the final DRS and indicating the problem.• Pat didn’t write a paperi. #Iti was great.

• If Pat writes a paperi, he loses iti. #Iti is under his bed.

• You can treat all of student, take, 4-pages-long, write, finished-at-4am, great, loses, and under-his-bed as predicates.

Related Documents