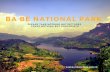

Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research REPORT 10 Ba Be National Park Site Description and Conservation Evaluation Frontier Vietnam 1997

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research

REPORT 10

Ba Be National ParkSite Description and Conservation Evaluation

Frontier Vietnam1997

Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research

Report 10

Ba Be National Park

Site Description and Conservation Evaluation

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J.(eds)

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural DevelopmentForest Protection Department

Frontier-VietnamInstitute of Ecology and Biological Resources

Society for Environmental Exploration

Hanoi1997

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 i

Technical report citation:

Frontier Vietnam (1997) Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (eds) Ba Be National Park: SiteDescription and Conservation Evaluation. Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10.Society for Environmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi.

Section citations:

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Description of the Ba Be National Park In Ba Be NationalPark: Site Description and Conservation Evaluation. pp. 4-12. Frontier Vietnam EnvironmentalResearch Report 10.. Society for Environmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology andBiological Resources, Hanoi.

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Vegetation survey In Ba Be National Park: Site Descriptionand Conservation Evaluation. pp. 13-22. Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10.. Societyfor Environmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi.

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Insects (excluding Lepidoptera) In Ba Be National Park:Site Description and Conservation Evaluation. pp. 23-26. Frontier Vietnam Environmental ResearchReport 10.. Society for Environmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and BiologicalResources, Hanoi.

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Butterflies In Ba Be National Park: Site Description andConservation Evaluation. pp. 27-30. Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10.. Society forEnvironmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi.

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Birds In Ba Be National Park: Site Description andConservation Evaluation. pp. 31-34. Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10.. Society forEnvironmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi.

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Mammals In Ba Be National Park: Site Description andConservation Evaluation. pp. 35-39. Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10.. Society forEnvironmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi.

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Socio-economics In Ba Be National Park: Site Descriptionand Conservation Evaluation. pp. 40-47. Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10.. Societyfor Environmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi.

Hill, M., Hallam, D. and Bradley, J. (1997) Tourism In Ba Be National Park: Site Description andConservation Evaluation. pp. 48-53. Frontier Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10.. Society forEnvironmental Exploration, UK and Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi.

© Frontier Vietnam

ISSN 1479-117X

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 ii

FOR MORE INFORMATIONForestry Protection Department

Block A3, 2 Ngoc Ha, Hanoi, VIETNAMTel: +84 (0) 4 733 5676Fax: +84 (0) 4 7335685E-mail: [email protected]

Frontier-VietnamPO Box 242, GPO Hanoi, 75 Dinh Tien Hoang

Street, Hanoi, VietnamTel: +84 (0) 4 868 3701Fax: +84 (0) 4 869 1883

E-mail: [email protected]

Institute of Ecology and Biological ResourcesNghia Do, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Vietnam

Tel: +84 (0) 4 786 2133Fax: +84 (0) 4 736 1196

E-mail: [email protected]

Society for Environmental Exploration50-52 Rivington Street, London, EC2A 3QP. U.K.

Tel: +44 20 76 13 24 22Fax: +44 20 76 13 29 92

E-mail: [email protected]: www.frontier.ac.uk

Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources (IEBR)The Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources (IEBR) was founded by decision HDBT 65/CT of theCouncil of Ministers dated 5 March 1990. As part of the National Center for Natural Science andTechnology, IEBR’s objectives are to study the flora and fauna of Vietnam; to inventory and evaluateVietnam’s biological resources; to research typical ecosystems in Vietnam; to develop technology forenvironmentally-sustainable development; and to train scientists in ecology and biology. IEBR isFrontier's principal partner in Vietnam, jointly co-ordinating the Frontier-Vietnam Forest ResearchProgramme. In the field, IEBR scientists work in conjunction with Frontier, providing expertise tostrengthen the research programme.

The Society for Environmental Exploration (SEE)The Society is a non-profit making company limited by guarantee and was formed in 1989. The Society’sobjectives are to advance field research into environmental issues and implement practical projectscontributing to the conservation of natural resources. Projects organised by The Society are joint initiativesdeveloped in collaboration with national research agencies in co-operating countries.

Frontier-VietnamFrontier-Vietnam is a collaboration of the Society for Environmental Exploration (SEE), UK andVietnamese institutions, that has been undertaking joint research and education projects within the protected areas network of Vietnam since 1993. The majority of projects concentrate on biodiversity andconservation evaluation and are conducted through the Frontier-Vietnam Forest Research Programme. The scope of Frontier-Vienam project activities have expanded from biodiversity surveys and conservationevaluation to encompass sustainable cultivation of medicinal plants, certified training and environmentaleducation . Projects are developed in partnership with Government departments (most recently the Instituteof Ecology and Biological Resources and the Institute of Oceanography) and national research agencies.Partnerships are governed by memoranda of understanding and ratified by the National Centre for NaturalScience and Technology.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 iii

TABLE OF CONTENTSList of Figures vExecutive Summary viAcknowledgements viii1.0 Introduction 12.0 Project aims 33.0 Description of the Ba Be National Park

3.1 General description3.1.1 Location3.1.2 History and status3.1.3 Previous studies

3.2 Physical environment3.2.1 Climate3.2.2 Topography3.2.3 Geology

3.2.4 Hydrology and catchment protection

44491010111112

4.0 Vegetation survey4.1 Introduction4.2 Methods

4.2.1 Vegetation mapping4.2.2 Vegetation transects4.2.3 Botanical collection

4.3 Results4.3.1 Vegetation mapping4.3.2 Vegetation transects4.3.3 Species list

4.4 Description of forest transect sites4.4.1 Forest Transect4.4.2 Forest Transect4.4.3 Forest Transect4.4.4 Forest Transect4.4.5 Forest Transect

4.5 Discussion4.5.1 Forest types4.5.2 Rare species4.5.3 Threats to the forest flora

13131313141616161718181819202021212122

5.0 Insecrs (excluding lepidoptera)5.1 Introduction5.2 Methods

5.2.1 Sweep-netting5.2.2 Pitfall trapping

5.3 Results5.3.1 Sweep-netting5.3.2 Pitfall trapping

5.4 Discussion5.4.1 Insects of the herb layers5.4.2 Ground-dwelling insects

23232323242424252526

6.0 Butterflies6.1 Introduction6.2 Methods

6.2.1 Butterfly transects6.2.2 Opportunistic collection6.2.3 Butterfly trapping

6.3 Results6.3.1 Species-richness6.3.2 Butterfly communities in different habitats

6.4 Discussion

272727272828282829

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 iv

6.4.1 Species-richness6.4.2 Species of interest6.4.3 Butterfly communities in different habitats

293030

7.0 Birds7.1 Introduction7.2 Methods7.3 Results7.4 Discussion

7.4.1 Range extensions7.4.2 Altitude reductions7.4.3 Rare species

31313232333334

8.0 Mammals8.1 Introduction8.2 Methods

8.2.1 Mammal trapping8.2.2 Bat netting8.2.3 Observation

8.3 Results8.3.1 Mammal trapping8.3.2 Bat netting8.3.3 Observation

8.4 Discussion8.4.1 Small mammals8.4.2 Bats8.4.3 Larger mammals and primates

35353535363636373738383838

9.0 Socio-economics9.1 Introduction9.2 Methods9.3 Results

9.3.1 The people and place9.3.2 Economic activities9.3.3 Land tenure9.3.4 Use of, and dependence upon, the forest9.3.5 Forestry protection authorities (Kiem Lam)

9.4 Discussion

404040404344454647

10.0 Tourism10.1 Introduction10.2 Methods10.3 Results

10.3.1 Present facilities10.3.2 Plans for development10.3.3 Tourist profile10.3.4 Interaction of tourists with environment, culture, economy

10.4 Discussion

4848484849505153

11.0 Conclusions 5412.0 References 5713.0 Appendices

Appendix 1: PlantsAppendix 2: Vegetation transect dataAppendix 3: Forest transect diagramsAppendix 4: ButterfliesAppendix 5: BirdsAppendix 6: MammalsAppendix 7: Medicinal plants used in Ba BeAppendix 8: Specimens

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 v

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 Map showing geographic position of Ba Be National Park 5Figure 2 Ba Be National Park, showing boundaries 6Figure 3 Ba Be National Park 7Figure 4 Ba Be National Park, showing study sites 8Figure 5 Number of taxa in major biological groups identified in earlier surveys 9Figure 6 Climate data for Cho Ra 10Figure 7 Topography of Ba Be National Park 11Figure 8 Vegetation map of Ba Be National Park 15Figure 9 Summary data for vegetation plots 16Figure 10 Ground flora data for vegetation plots 17Figure 11 Ground flora species in ecological groups 17Figure 12 Summary of sweep-net data for five sites 24Figure 13 Summary of pitfall trap data for six sites 24Figure 14 Pitfall fauna in major invertebrate groups 25Figure 15 Distribution of butterfly species between families 28Figure 16 Summary statistics for butterfly transects 29Figure 17 Percentage of total number of butterfly individuals in each family 29Figure 18 Bird species outside their normal altitude range 33Figure 19 Results of small-mammal trapping 36Figure 20 Mark-release-recapture data for small mammals 37Figure 21 Population of Ba Be district 41Figure 22 Changing demography of Ba Be National Park 41Figure 23 Map showing villages, markets and subdistricts of the National Park 42Figure 24 Ethnic groups of Ba Be 43

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 vi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report describes a biodiversity survey of the Ba Be National Park, Cao Bangprovince, Vietnam, conducted as a part of the Society for Environmental Exploration(SEE) Vietnam Forest Research Programme in October-December 1996.

The Ba Be National Park is 7,611ha in area, and is centred on Ba Be lake, Vietnam’sonly significant mountain lake. Surrounding the lake, limestone hills support a mosaicof tropical forest vegetation types and cleared areas used by local people for grazinglivestock.

The SEE survey at Ba Be involved the study of forest ecosystems, and biodiversity ofplants, butterflies, birds and mammals. In addition, the socio-economic conditions ofthe resident human populations were investigated, and the growing tourist industry ofthe area studied.

Five forest plots were studied in detail, in various locations around the lake and at avariety of altitudes. Most of the sites showed some signs of human disturbance, and inplaces this was intense. The forests studied fell into two main types. Those on barelimestone slopes showed a low tree species diversity and were dominated by the treesStreblus tonkinensis and Burretiodendron hsienmu. The herb layer of these forests onlimestone contained few herbaceous species. In localities where deeper layers of soilhad built up, such as at the base of slopes and the top of ridges, the forest contained agreater diversity of trees, and a more developed field layer containing severalherbaceous species.

Of the plant species identified, nine are endangered within Vietnam (they are listed inthe Red Data Book for Vietnam Volume 2, Plants; RDB, 1995). The endangeredspecies are mainly valuable timber trees or herbs used in traditional medicine.

The butterfly fauna of two secondary forest areas and grassland beside the River Nangwere compared using transect methods. The highest diversity of butterflies wasrecorded in one of the transects located in woodland, although by far the greatestnumbers of butterflies were recorded in the open site. Overall, 167 butterfly specieswere collected at Ba Be.

The bird fauna of Ba Be was studied by observation. Overall, 189 species of bird wererecorded. Thirteen of these species were observed well below their normal knownaltitude ranges. Two species recorded are endangered within Vietnam, and eight‘near-threatened’ internationally.

Mammals were studied by observation, small-mammal trapping, and bat-netting.Overall a list of 22 mammal species was produced. Three of the species recorded(slow loris, Francois’ leaf monkey and Owston’s palm civet) are vulnerable toextinction internationally.

Socio-economic surveys were carried out by interview with the ethnic minorityinhabitants of the area. Most of the local people belong to the Tay minority, and are

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 vii

heavily reliant on agriculture as a source of income. Hunting is common in the forest,and local people fish the lake using explosives. Both of these activities are banned inthe National Park but still continue; dynamite fishing in particular is widespread andobvious.

Ba Be National Park is developing as a tourist destination, both for domestic andoverseas tourists. Visitors to the Park were interviewed to assess their impact on thelocal ecology and economy and to gather their views on the Park. The tourist industrycurrently has little effect on the lifestyles of local inhabitants, and the ecologicaleffects of tourism have been slight, when compared with the impact that hunting,timber removal and agriculture have on the forest areas.

Ba Be is a landscape of national importance within Vietnam, and its forests supportpopulations of certain endangered species. Its designation as a National Park hasreduced, but not eliminated, the major problems common to most Vietnameseprotected areas; hunting, fishing, timber exploitation and clearance for agriculture.However, the natural beauty of the area and its relative accessibility from Hanoi hasencouraged tourism at Ba Be. If the development of the tourism industry is managedeffectively and sustainably, involving local people, then the National Park has thepotential to generate income and reduce some of these problems.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environmental Research Report 10 viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis report is the culmination of the advice, co-operation, hard work and expertise of manypeople. In particular acknowledgements are due to the following:

IEBRBotanist Dr. Nguyen Kim DaoMammalogist Dr. Pham Duc TienBotanist Dr. Ha Van TueSocio-economist Lai Phu HoangOrnithologist Dr. Truong Van LaParasitologist Nguyen Anh TungParasitologist Pham Ngoc Doanh

SOCIETY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EXPLORATIONManaging Director: Ms. Eibleis FanningDevelopment Programme Manager: Ms. Elizabeth HumphreysResearch Programme Manager: Ms. Leigh StubblefieldOperations Manager: Ms. Amy Banyard-Smith

HANOI UNIVERSITYEntomologist Pham Dinh Sac

FRONTIER-VIETNAMProject Co-ordinator: Mr. M. HillResearch Co-ordinators: Mr. D. Hallam and Mr. J. BradleyAssistant Research Co-ordinators: Ms. Maysie HarrisonResearch Assistants: Mr. Russell Adams, Ms. Paula Carvalho, Ms. Nicola

Field, Mr. Kevin Gleave, Mr. Colin Godfrey, Mr.James Hopper, Mr. Richard Hourston, Ms. EllieKinross, Mr. Matthew Kneller, Mr. David Lee, Mr.James Miln, Ms. Robyn Mitz, Mr. Stuart Poole, Mr.Andre Raine, Ms. Jenny Twaddell and Ms. StephanieWates.

RUSSIA- VIETNAM TROPICAL CENTREEntomologist Dr Alexander Monastyrskii

Editorial comment Ms. L. Stubblefield, SEE.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 1

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Vietnam stretches from 23oN in the North to 8o30’N in the South, supporting a widerange of habitats and biodiversity. The natural vegetation was once dominated bytropical forests, but these have undergone a rapid decline in the present century. In1943, approximately 44% of the country's land area was forest. By 1983, this haddeclined to 24% (MacKinnon, 1990). The area covered by good-quality natural forestsis only around 10% of the land area, and, of this, only around 1% could be describedas pristine (Collins et al.,1991).

The natural forest vegetation of lowland Vietnam is dominated by two main types(WWF & IUCN, 1995); tropical wet evergreen (and semi-evergreen) forest, andtropical moist deciduous forest (monsoon forests). Wet evergreen forest is found inareas with a regular, high rainfall (>1500mm per annum), and is largely restricted inVietnam to the South and Central regions (WWF & IUCN, 1995). Monsoon forestsexperience a distinct dry season and are dominated by deciduous tree species(Whitmore, 1984). They dominate inland and Northern Vietnam, an area classified byUdvardy (1975) as 'Thailandian Monsoon Forest'.

A third major forest formation, forest over limestone, is important in areas oflimestone geology and supports a range of endemic herbs (WWF & IUCN, 1995).

At higher altitudes (700m and above) lowland forest gives way to montane forestformations, which differ from lowland forests in their distinctive physical structureand floral composition (Whitmore, 1984; Collins et al., 1991).

In addition to these terrestrial forest types, coastal areas of Vietnam support mangroveand (in the South) Melaleuca forests, and there are small areas of fresh-water swampforest in low-lying areas of southern Vietnam (Government of SRV, 1994).

Forests support the greatest part of Vietnam's biodiversity, which includes a highproportion of endemic plant species (Thai Van Trung, 1970) and birds (ICBP, 1992).Two Red Data Books have been prepared for Vietnam; Volume 1, Animals (RDB,1992), lists 366 species under threat, and 350 plant species are included in Volume 2(RDB, 1996). Several endangered species, including the Kouprey (Bos sauveli), JavanRhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), Tiger (Panthera tigris), Asian Elephant (Elephasmaximus) and Saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) are facing imminent extinction.

Forest degradation and the loss of biodiversity have been caused by a number offactors. Two major wars since 1946, and more local border disputes, contributed to aloss of forest cover and increased levels of poaching. Between 1961 and 1971, 2.6million ha of terrestrial forest in South Vietnam was subject to aerial herbicidebombardment at least once (Mai Dinh Yen & Cao Van Sung, 1995). Strategicallysituated lowland forests were cleared by American troops using 'Rome ploughs'(MacKinnon, 1990). Direct war damage was less extensive in the North of thecountry, although indirect forest loss, for example clearance to increase agricultural

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 2

production, occurred throughout Vietnam (MacKinnon, 1990). Overall, around 14%of the Vietnam's forest cover was lost between 1943 and 1975 (MacKinnon, 1990).

Since reunification in 1975, forest loss has continued. It has been promoted by severalfactors, most notably the pressure on land caused by the country's large and rapidlyincreasing population. In 1994, the population of Vietnam was approximately 72.5million (General Statistical Office, SRV., 1995), with a growth rate of 2.1% per year.About 80% of the population live in rural areas (Government of SRV, 1994), wherepopulation growth may encourage clearance of forest land for agriculture, as well asincreasing the exploitation of forest products.

The decline in the quantity and quality of Vietnam's native forests was addressed bythe publication in 1990 of the Tropical Forestry Action Plan for Vietnam(MacKinnon, 1990), which pointed out the lack of adequate management plans orinventories for many of the protected areas in Vietnam. Since this time, the protectedareas system has been revised and extended. There are now 87 protected areas inVietnam, covering 976,000ha (Cao Van Sung, 1995); this figure includes NationalParks, Nature Reserves and Protected Forests. In some of these areas, biodiversityinventories have been carried out (by Vietnam's Forest Inventory and PlanningInstitute, FIPI, and foreign NGOs including Worldwide Fund for Nature, Flora andFauna International, and Birdlife). Despite this, the BDAP of 1994 was still able toidentify several reserve areas which lack basic biodiversity surveys and managementplans (Government of SRV, 1994).

The Society for Environmental Exploration's Vietnam Forest Research Project wasestablished in 1993, in collaboration with the Ministry of Forestry. Working togetherwith the Institute for Ecology and Biological Resources, Hanoi, and the University ofHanoi, it has conducted research in several protected areas and plans to develop along-term research base in one important reserve.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 3

2.0 PROJECT AIMS

The overall aims of the survey work carried out by the SEE Vietnam Forest ResearchProgramme include;

• To conduct baseline biodiversity surveys in protected areas in the North ofVietnam;

• To investigate the socio-economic conditions of the human inhabitants of theseprotected areas, in order to evaluate the benefits derived from forest reserves, andthreats posed by human exploitation;

• To provide information on the biological values and threats to forest reserves, toassist in the development and execution of management plans in those areas.

The aims of each survey period carried out include;

• To map the extent of major vegetation types within the study area, and carry outdetailed vegetation sampling on forest plots (40x40m) and transects (60x10m);

• To make a quantitative comparison of butterfly diversity in different habitats, andmake a collection of all species;

• To collect specimens of small terrestrial mammals (rodents and insectivores) andbats for identification, in order to compile as complete as possible a species list ofthese groups for the site;

• To record birds and large mammals present, through extensive observation of thehabitats represented at the site;

• To collect data on the lifestyles of local people, by interview and questionnaire,

with particular emphasis on their utilisation of forests, and to interview localgovernment and forestry protection officials, in order to determine their views onthe future development of the reserve;

• To collect data on the tourist industry in the National Park.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 4

3.0 DESCRIPTION OF BA BE NATIONAL PARK

3.1 General description

3.1.1 Location

Ba Be National Park is located in Nam Mau commune, Cao Bang Province, northernVietnam, co-ordinates 22o24'N by 105o37'E (see Figure 1). It is 254km from Hanoi,and 18km South-West of the town of Cho Ra. In the centre of the National Park is BaBe lake, the only significant mountain lake in Vietnam (Scott, 1989).

The total area of the National Park is 7,611ha, of which 3,226ha make up a strictlyprotected zone, and 4,083ha the "tourist subzone" (Cao Van Sung, 1995); the lakesurface accounts for 301ha of the park's area (see Figure 2).

The Park falls within biogeographical subunit 6a (South China) of the biogeographicalclassification of the IndoMalayan realm developed by MacKinnon and MacKinnon(1986).

3.1.2 History and status

Ba Be was recognised as a 'cultural - historical and environmental reserve', to protectits landscape and historical relics, in 1977. In 1992, it was established as a NationalPark (Cao Van Sung, 1995). A management plan for the National Park was producedin 1991 (Government of SRV, 1994).

Vietnam's Tropical Forest Action Plan (MacKinnon, 1990) proposed that the NationalPark be extended from its current 7,611ha to around 44,000ha. The BiodiversityAction Plan for Vietnam (Government of SRV, 1994) has proposed that themanagement of the Ba Be National Park and the Na Hang Nature Reserve, 30kmaway in Tuyen Quang province, be integrated. Under this plan, which has yet to beimplemented, the reserves would be extended and 'forest corridors' between the twoareas protected. The National Park will now be extended in 1997 to a total of49,000ha, taking in land to the South of the existing protected area (see Figure 2).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 5

Figure 1. Map showing the geographic position of Ba Be National Park.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 6

Figure 2. Map showing the boundaries of Ba Be National Park.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 7

Figure 3. Ba Be National Park.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 8

Figure 4. Ba Be National Park, showing study sites.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 9

3.1.3 Previous studies of the National Park

Previous studies of the biodiversity of the Ba Be National Park have included a surveyby Vietnamese scientists in 1990 (FIPI, unpublished), which formed the basis for theNational Park management plan. A later study by the Society for EnvironmentalExploration (Kemp et al., 1994) involved surveys of vegetation, birds, mammals andbutterflies (which were not collected in the course of the earlier FIPI study). Numbersof species identified for the National Park are listed in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Number of species identified in previous biodiversity surveys of Ba Be

FIPI (1991) Kemp et al. (1994)Plants - 411Mammals (including bats) 38 (2) 31 (11)Birds 111 111Reptiles 18 -Amphibians 6 -Fish 49 -Butterflies - 52

The mammal list obtained in the 1994 Frontier study (Kemp et al., 1994) includedspecies only identified by interview with local people, and some of the mammalslisted may no longer exist in the Park. For example, the highly threatened Tonkinsnub-nosed monkey (Pygathrix avunculus) was recorded. Although Ba Be is part ofthe historic range of this species, it seems highly unlikely that any survive there today(Cox, 1994), and the species was not recorded in the present survey.

In 1989, Ba Be National Park was visited as part of a survey of threatened primates inNorthern Vietnam (Ratajszczak, 1990), in which the population of Francois' leafmonkey Trachypithecus francoisi francoisi was studied.

3.2 Physical environment

3.2.1 Climate

Ba Be National Park has a mild tropical climate, dominated by the summer monsoon.Winters are cool and relatively dry, summers hot and wet. The majority of annualrainfall occurs between the months of June and September (Kemp et al., 1994), whenthe rainfall increases to 7-12 times the monthly average (SCEMMA, 1992).

Mean climatic data collected at the Cho Ra meteorological station (2.2km from BaBe), over the period 1961-1985 are shown in Figure 6.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 10

Figure 6. Average annual meteorological statistics for Cho Ra (from SCEMMA,1992).

Average air temperature 22oCMax. air temperature 39oCMin. air temperature 0.6oCAverage annual rainfall 1378mmAverage humidity 83%

3.2.2 Topography

Ba Be lake is 170m above sea level, and is surrounded by limestone peaks whichslope steeply, reaching 893m asl (Scott, 1989). Further from the lake, there are higherpeaks including Pia Booc (1,520m, 4.5km from the lake), Hoa Son (1,517m, 11.5kmfrom the lake), and Pu Sam Sao (1,175m, 11km from the lake) (SCEMMA, 1992).The topography and geological features of Ba Be National Park are shown in Figure3.

The majority of the land area of the National Park is made up of steep limestoneslopes and cliffs, and the only flat land occurs beside the River Nang and in someplaces beside the lake. All of this land has been converted to agricultural uses.

The lake contains numerous small islands, with a combined surface area of 1.4ha.(SCEMMA, 1992).

3.2.3 Geology

The underlying geology of the National Park area is limestone, which has beeninfluenced by denudation and karstic processes. A number of caves have formed, thelargest being the Puong Grotto, 300m long and 30-60m high (Cao Van Sung, 1995).

Karst basins (dry depressions surrounded by peaks and ridges) have also been formedin the limestone.

Throughout the reserve, limestone is exposed as cliffs or karst. Due to the steeptopography, soil accumulation is patchy, with pockets of soil occurring between rockoutcrops. Where soils have built up, they are alkaline and clay-rich (Kemp et al.,1994).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 11

Figure 7. Topography of Ba Be National Park and extension zone.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 12

3.2.4 Hydrology and catchment protection

The lake is 7.5km long, and 200m-800m wide (mean width 500m) (Cao Van Sung,1995). At its deepest point, it is 29m deep (Kemp et al., 1994). The lake is fed by theTho Leo River, which enters the lake at its southern end. Two other small rivers (NamBan Tao and Bo Lu River) flow into the lake from the West.

Water drains from the lake into the Nang River to the North. During the rainy season,water flow into the lake can cause lake levels to rise as much as 2.8m (Kemp et al.,1994), but water never flows from the Nang River into the lake, even at times ofheavy rain (SCEMMA, 1992).

The lake plays an important role in the regulation of flooding on the Nang River as,when the Nang is flooded the flow from the lake into the Nang ceases and lake levelsrise. The lake can retain up to 8.4 million m3 in this way (SCEMMA, 1992).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 13

4.0 VEGETATION SURVEY

4.1 Introduction

Vietnam's flora is composed of at least 8,000 vascular plant species, 10% of which areendemic (IUCN, 1986). The geographical position of the country, together with thewide range of environmental conditions allow a variety of floral elements to survivehere. In the evergreen rain forests of the South, the family Dipterocarpaceae aredominant, along with other elements of the Malesian (southern) flora (Nguyen NghiaThin, 1995). In the Hoang Lien Son mountain range of the North, there is a mixture ofsubtropical and temperate species characteristic of the flora of southern China and theHimalayas (Nguyen Nghia Thin & Harder, 1996). Areas of particularly high botanicalbiodiversity in Vietnam were mapped by Schmid (1993). The forests of Vietnam haveparticular significance for the conservation of biodiversity of both plants and animals.

The physical and biological characteristics of forest in any site are influenced by localclimate, geology, altitude and topography (Whitmore, 1984), as well as biotic, humanand historical factors. The nature of the forest in turn influences the fauna, an effectthat is most visible where animals have a particular foodplant or niche requirementwithout which they cannot survive (host-plant specificity is shown, for example, bythe Lepidoptera; Holloway, 1984). The absence or loss of one species is likely to havehigher order effects, influencing species higher in food chains (Turner, 1996). Inreality, one protected area is likely to contain a patchwork of forest types influencedby the environmental gradients in operation in the area, and the patchiness of humanexploitation.

The aims of the vegetation work carried out during the survey were to describe thedominant vegetation types of the survey area, and produce a species list for plants ofthe protected area.

4.2 Methods

4.2.1 Vegetation mapping

The distribution of major vegetation types (primary and secondary forest, scrub,grassland and arable land) in the study area was mapped by observation from severalhigh viewpoints.

4.2.2 Vegetation Transects

4.2.2.1 Site selection

Vegetation transect studies were carried out at five sites. Sites were selected torepresent the altitudinal range found in the National Park, and were spread around thelake (see Figure 4), in order to include the main forest types in the area. At each of thesites FT1-FT5, data were gathered on the trees and ground flora.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 14

4.2.2.2 Forest trees

At each site, a 40m x 40m plot was marked using barrier tape. Within this plot, everytree (woody plants > 4.5m in height) was identified to species level, and the Diameterat Breast Height (DBH, 1.3m above ground level) recorded.

In addition, a 60m x 10m transect was laid out at each of the five sites, to gather datafor the construction of forest profile diagrams. For each tree in the transect, trunk co-ordinates, DBH, canopy extent, and tree heights were recorded, and the tree identifiedto species level. Every tree was also sketched in the field.

4.2.2.3 Ground flora

Ground flora was studied in 20 2m x 2m quadrats placed diagonally through the 40mx 40m plot (covering 5% of the ground area of the plot).

Within each quadrat, all tree seedlings and shrubs (woody plants < 4.5m in height),herbs, lianas and palms were identified. For each of these species, the number ofindividuals and percentage cover of the quadrat were recorded. In addition, the totalpercentage cover (and percentage bare ground) of the ground layers was recorded.

From this data, diversity was calculating using Fisher's α. This measure of diversitytakes account both the number of species (here, Recognisible Taxonomic Units orRTUs were used, as many of the taxa such as tree seedlings could not be identified tospecies level) and individuals in a sample (Fisher et al, 1943). Fisher's α is relativelyfree of bias when describing samples of differing size (see Magurran, 1988).

4.2.3 Botanical collection

Botanical specimens were collected throughout the study area in a variety of differenthabitats. Identification in the field was achieved using Vietnam Forest Trees (FIPI,1996) and Cayco Viet Nam (Pham Hoang Ho, 1993). For species which could not beidentified in the field, herbarium specimens were collected for later identification.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 15

Figure 8. Vegetation types of Ba Be National Park.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 16

4.3 Results

4.3.1 Vegetation mapping

A vegetation map for the study area is shown in Figure 8.

The vegetation of Ba Be National Park and its surrounding buffer zones is largelymade up of forest, although there are extensive areas of clearance for cultivation andgrazing within the reserve. The majority of the forest is secondary in nature, havingbeen extensively utilised by local populations in the past (and at present in someareas).

4.3.2 Vegetation transects

4.3.2.1 Sites chosen

The five sites chosen can be classified as described by Whitmore (1984);

• FT1 Lowland forest over limestone, 710m above sea level.• FT2 Lowland forest over limestone, 175m asl.• FT3 Lowland tropical moist forest, 300m asl.• FT4 Lowland tropical moist forest, 750m asl.• FT5 Lowland forest over limestone, 475m asl.

4.3.2.2 Forest trees

A summary of the data on forest trees from the plots FT1-FT5 is shown in Figure 9.For each of the sites, the basal area of wood was calculated for each tree species in theplot, in order that the relative importance of each plant family represented could beascertained. These data are shown in Appendix 2.

Figure 9. Summary of tree data for forest sites

Site Altitude(m asl)

Number offamiliesper plot

Number ofindividualsper plot

Number ofstems per plot

Numberof stemsper ha.

Total BasalArea of wood(m2ha-1)

FT1 710 5 104 106 663 40.44FT2 175 10 90 95 594 24.99FT3 300 17 143 163 1019 23.64FT4 750 24 184 184 1150 47.99FT5 475 9 118 118 737 32.19

Transect diagrams for the forest sites studied are shown in Appendix 3.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 17

4.3.2.3 Ground flora and tree seedling survey

Figure 10 shows a summary of the data for the sites, and Figure11 shows the totalnumbers of plants in each ecological class in each location.

Figure 10. Summary of the ground flora data for five forest sites.

Site Mean cover(% of quadrat)

Mean number ofspecies per quadrat

Mean number ofspecies m-2

Fisher's αdiversity index

FT1 56.60 4.15 1.04 3.560FT2 36.90 5.65 1.41 7.466FT3 52.55 10.30 2.57 13.015FT4 53.00 10.25 2.56 17.211FT5 33.80 4.00 1.00 2.107

Figure 11. Numbers of plants in each ecological group identified, for five forest sites.

NI = Number of individual plants NS = Number of speciesHERBS CLIMBERS PALMS SHRUBS TREES

Site NI NS NI NS NI NS NI NS NI NSFT1 6 4 24 10 0 0 18 5 6948 8FT2 2 2 12 7 0 0 8 4 1782 28FT3 59 8 55 12 0 0 5 2 621 32FT4 109 3 14 6 51 2 30 8 448 44FT5 6 2 10 3 0 0 4 2 2564 8

4.3.3 Species list

The list of plant species found in this survey is shown in Appendix 1. A total of 551species, belonging to 136 plant families, were identified during the study period. Thiscompares to a total of 411 species, from 106 families, identified by Le Mong Chan inthe Ba Be National Park in 1994 (Kemp et al, 1994). Together, the lists from the tworecent surveys of the park's vegetation comprise 603 plant species in 137 families.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 18

4.4 Description of forest transect sites

4.4.1 Forest Transect 1

FT1 was located on the western side of the lake, close to the Hmong village of NamGiai at an altitude of 710m asl. The forest studied grew on a steep (around 30o),North-East facing limestone slope covered with a scree of limestone boulders. Theproximity of the village meant that this area was easily exploited for wood and timber.As a result of human and physical disturbance on the site, the diversity of woody taxawas extremely low, and highly valued timber species such as Markhamia spp. (familyBignoniaceae) and Chukrasia tabularis (Meliaceae) were rare.

The forest showed three distinct layers, the upper canopy (to 45m), mid-canopy (5-20m) and shrub and sapling layer (below 4.5m). The upper canopy was incomplete(perhaps as a result of logging, or due to natural disturbance on the steep slope), andwas dominated by the tree Burretiodendron hsienmu (Tiliaceae). The lower canopywas almost completely composed of Streblus (Teonongia) tonkinensis (Moraceae), atree which has been found in single-species stands in previously clear-felled areas offorest at the nearby Na Hang Nature Reserve (Hill & Hallam, 1997).

Perhaps due to the dense shade caused by the mid-canopy of Streblus tonkinensis, theshrub and ground layers of vegetation contained very few species adapted topermanent existence on the forest floor; only four herb and five shrub species, and nopalms, were found. Tree seedlings were the dominant forms in this layer, particularlyStreblus and Burretiodendron.

4.4.2 Forest Transect 2

FT2` was only a little above the level of Ba Be lakes, at around 175m asl., close to the'Fairy Pool', on a North-West facing slope. Although at a lower elevation than FT1,the forest showed superficial similarities to that at the previous site. It was located ona steep slope of limestone boulders (the mean slope over the 60m transect studied was36o), and was again dominated by the two species Streblus tonkinensis andBurretiodendron hsienmu. S. tonkinensis made up 82% of the individual trees in theplot, and 29% of the basal area of wood, whereas B. hsienmu were 3% of theindividuals but 33% of the total basal area of wood.

The woody plant diversity at FT2 was, however, slightly higher than that at FT1; 10plant families were represented. The upper canopy included Diospyros sp.(Ebenaceae) in addition to B. hsienmu. The lower canopy included, in addition to S.tonkinensis, Streblus macrophyllus (Moraceae), Albizia kalkora (Fabaceae),Deutzianthus tonkinensis (Euphorbiaceae), and Ailanthus triphysa (Simaroubaceae).

The shrub- and ground flora layers (below 4.5m) were again dominated by seedlingsof the canopy trees Streblus tonkinensis and Burretiodendron hsienmu. In addition,Streblus macrophyllus was common. A larger range of tree seedlings was present in

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 19

the ground flora than at FT1, reflecting the greater diversity of forest trees at this site.The only herbs represented were a fern and Laportea sp. (Urticaceae). Climbersincluded Stephania rotunda (Menispermaceae), Entada phaseoloides (Fabaceae), andPothos sp. (Araceae).

4.4.3 Forest Transect 3

FT3 was situated in the buffer zone of Ba Be National Park, to the North of the lakeand on a hillside near the Tay village of Ban Cam. The elevation of the site was 300masl and the site was South-facing. The gradient of this site was again steep (30o), but,unlike the earlier locations FT1 and FT2, a more complete soil layer existed at thissite. Exposed limestone boulders were present, but they did not form a continous screeslope as at FT1 and FT2.

The diversity of woody species present was much higher here than in the othertransects studied. Seventeen plant families were represented in the tree flora.

In contrast to the earlier sites, the trees of the upper canopy layer were relativelysmall, with few reaching over 20m in height. However, as at the earlier sites,Burretiodendron hsienmu (Tiliaceae) was again the dominant species of the uppercanopy (since the trees present were smaller, this species only made up 16% of thetotal basal area of wood at FT3). Other species present in the emergent layer includedAdenanthera pavonina (Fabaceae), Stereospermum sp. (Bignoniaceae), Diospyros sp.(Ebenaceae), and Amoora gigantea (Meliaceae).

The lower canopy (10-20m) differed greatly from that at FT1 and FT2. Streblustonkinensis, dominant in the two earlier plots, was rare. However, the Moraceae wasagain the main plant family, represented by Streblus macrophyllus and Ficus spp. inaddition to S. tonkinensis.

The species diversity in the ground layers was relatively high. Tree seedlings werepresent in small numbers, although a wide range of species were represented,reflecting the diversity of the canopy layers. The most abundant tree seedlings werethe Moraceae (Streblus macrophyllus, S. tonkinensis, and Broussonetia papyrifera),and Rutaceae (Evodia meliaefolia and Clausena lansium). The Ebenaceae (Diospyrosspp.) and Tiliaceae (Burretiodendron hsienmu) were also relatively abundant.Climbing plants included Entada phaseoloides (Fabaceae), Zehneria maysorensis(Cucurbitaceae), Fissistigma thorelli (Annonaceae), and Dioscorea sp.(Dioscoreaceae). Common herbs included the ferns Pteris aff. ensiformis andAdiantum spp. (2 species), and, in more open areas, Mosla sp. (Lamiaceae).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 20

4.4.4 Forest Transect 4

FT4 was situated approximately 500m from the main path from the lakeside to NamGiai village, at 750m asl. In parts of the transect, a relatively deep layer of soil hadbuilt up.

Probably because of the soil conditions in this location, FT4 showed a well-developedupper canopy of very tall trees (30-40m). Among the more important familiesrepresented in this layer were Fabaceae (Ormosia sp.), Magnoliaceae, Lauraceae(Litsea cubeba) and Tiliaceae (Burretiodendron hsienmu), although no single specieswas dominant. The middle canopy was also highly diverse, and Streblus tonkinensisvirtually absent. Important families in this layer included the Myrsinaceae (Ardiseasp.), and Rubiaceae (Wendlandia spp. and Randia sp.). This plot showed the greatestnumber of woody plant families, and the highest basal area of wood per hectare (dueto the presence of many large trees).

The ground flora at FT4 was diverse, with a large number of tree species present asseedlings and saplings. Two species of palm (Arecaceae) were present, one of them(Calamus sp.) being particularly abundant. The commonest herb species wasOphiopogon reptans (Convallariaceae).

4.4.5 Forest Transect 5

FT5 was located on the rocky slope of a limestone basin, above Ba Be village (Southof the lake), at an altitude of 475m. The floor of the basin had recently beenselectively logged, with most of the large trees being removed. The forest on thesurrounding slopes was less disturbed.

The transect included around 10m of the basin floor, which was dominated by youngtrees of the family Ulmaceae, and 50m of limestone slope, where Streblus tonkinensiswas the most abundant tree. Burretiodendron hsienmu was an important element inthe upper canopy.

The ground flora of this site was sparse and made up of few species, showing thelowest diversity of any of the sites. As at FT1 and FT2, the ground layer wasdominated by regenerating seedlings of the dominant tree species.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 21

4.5 Discussion

4.5.1 Forest types

The forests studied can be classified into two main types;

• Streblus/Burretiodendron forest on limestone slopes (FT1, FT2, FT5);• Mixed lowland rainforest on deeper soils (FT3, FT4).

The former type occurs over a greater area in the National Park than the latter.

Streblus/Burretiodendron forest is generally characterised by a low species diversity,and, particularly, little ground flora. The ground flora is heavily dominated byregenerating seedlings of the dominant tree species, and there are few permanentmembers of the ground flora (forest herbs). This forest type occurs on steep, rockylimestone slopes, where natural disturbance is common, or in areas which have beendisturbed by logging.

Where deeper soils have accumulated, a more mixed forest is favoured with a greaterdiversity of forest trees. Although the Moraceae may still be an important plant familyin these forests, the family is represented by a greater range of taxa including Streblusspp., Ficus spp., and Broussonetia papyrifera. These forests are characterised by adiverse ground flora, including forest herbs and (sometimes) palms.

4.5.2 Rare species

Ten of the species found at Ba Be are listed in the Red Data Book of Vietnam (RDB,1994), which describes species threatened with extinction nationally (see Appendix1). Two of these (the fern Cibotium barometz and Acanthopanax gracilistylis,Araliaceae) are classified as 'Insufficiently Known'; that is, there is insufficient dataon their distribution to draw conclusions on their status. Of the remaining sevenspecies, five are classed as 'Rare', and two are placed in the higher threat category'Vulnerable'.

Two major threats to individual plant species are the over-exploitation of high-valuetimber species, and the collection of plants for use in traditional medicine. Speciesexploited for timber include Markhamia stipulata (Bignoniaceae) and Chukrasiatabularis (Meliaceae) (FIPI, 1996). Those that are gathered for use in traditionalmedicines include Stephania brachyandra (Menispermaceae) and Smilax glabra(Smilacaceae) (RDB, 1994). Others are threatened by forest loss, in combination withcollection as ornamental plants (in the case of, for example, Cycas balansae; NguyenKim Dao, pers. comm.).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 22

4.5.3 Threats to the forest flora of Ba Be National Park

Much of the forest in the park is secondary in nature, and has been heavily exploitedby man in the past. There are few areas which display the characteristics of primaryforest. Unfortunately, logging appears to be continuing even within the National Park;the remains of small logging camps were found throughout the forest, and felling wasobserved near the village of Nam Giai. The area has a relatively high humanpopulation and, although the best forest areas are some distance from settlements, thelake at the centre of the park allows access to remote forests.

Timber extraction occurs on a relatively small scale, but clearance and degradation ofpreviously forested areas for agricultural purposes is extensive. Although the forestsbordering the lake appear to be intact, behind a forested strip of shoreline there areextensive clearings for the cultivation of maize and rice. Even where families havebeen resettled in villages some distance from their land (for example, below Nam Giaivillage), they return to cultivate rice and other crops.

On the western side of the lake, agriculture has had a particularly disruptive influenceon forest cover; much of the flatter land has been cleared for arable cultivation,steeper slopes are clothed with poor secondary forest and bamboo thickets, wherecattle are free to graze, ensuring further degradation of this natural and semi-naturalvegetation.

Ba Be is unusual among Vietnamese protected areas in that its buffer zones includeland which is still under forest cover. For example, FT3 was carried out in the bufferzone to the North of the park. In many Vietnamese protected areas, land designated asbuffer zones has been completely denuded and has little or no biological value(Government of SRV, 1994). It is possible that the buffer zones at Ba Be could beused to promote sustainable forest use, alleviating pressure on the forests in the mainbody of the National Park.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 23

5.0 INSECTS (excluding Lepidoptera)

5.1 Introduction

The insects form the most diverse group of living organisms, and the centre of theirbiodiversity is in tropical forests (Stork, 1988). Insects dominate the food webs oftropical forests, and are important pollinators of forest plants (Greenwood, 1987).However, despite (or, perhaps, because of) this diversity, forest insects are little-studied, with the exception of the Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), which areconsidered in a separate chapter of this report. The huge diversity of tropical forestinsects makes detailed taxonomic work difficult, and it is often necessary to work onmorphospecies or Recognisible Taxonomic Units (RTUs). Unfortunately, the use ofRTUs limits the ecological information can be derived from invertebrate assemblagedata (Biological Survey of Canada, 1994).

5.2 Methods

Two methods were used to quantitatively sample insects, sweep netting and pitfalltrapping. Both are commonly used collection techniques, discussed by Southwood(1978), Biological Survey of Canada (1994), and other authors.

5.2.1 Sweep-netting

Sweep-netting was carried out in all the Forest Transect sites (FT1-FT5), between21st-24th November 1996. In each case, 500 sweeps were made through thevegetation of the field and shrub layers of the forest plot. Invertebrates were collectedfrom the net using a pooter and preserved in 70% ethanol. Later, they were sorted intoRecognisible Taxonomic Units (RTUs) or morphospecies.

5.2.2 Pitfall Trapping

Pitfall trapping was carried out at one site on the floodplain near camp (see Figure 4),and all the Forest Transect sites FT1-FT5. In each locality, pitfall traps were laid outin an array of four traps, with metal vanes running between them. A dilute (10%)formalin solution was used as the preservative (salt solution is recommended by theBiological Survey of Canada, 1994; but this does not always prevent the decay ofinvertebrate specimens in tropical conditions, requiring frequent checking of thetraps). Trapping was carried out for six nights in each location.

At the end of each trapping period, invertebrate specimens were placed in 70%ethanol for preservation, and sorted to RTUs as for the sweep-net assemblages.

Two measures were calculated in order to describe the insect assemblages caught;Fisher's α diversity index (Fisher et al., 1943), and the dominance measure d (Bergerand Parker, 1970), the proportion of the total number of individuals in a sample whichbelong to the most abundant species. Methods follow Magurran (1988).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 24

5.3 Results

5.3.1 Sweep-netting

Members of three arachnid orders, nine insect orders, and two other invertebrategroups (Mollusa and Isopoda) were captured in the sweep-net samples. A summary ofthe sweep-net data is given in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Summary of sweep-net data for five forest sites.

Site No. RTUs No. of Individuals α d

FT1 43 121 23.83 0.488FT2 41 78 34.96 0.115FT3 46 95 35.13 0.189FT4 56 106 48.09 0.075FT5 47 96 36.39 0.073

Sweep-net samples were small, with few individuals taken. Perhaps as a result of this,values for Fisher's α diversity index were relatively large. Values for the Berger-Parker index of dominance varied greatly, but, as is generally the case, those sampleswhich showed the highest degree of dominance by one species (particularly FT1) alsohad the lowest α diversity.

5.3.2 Pitfall trapping

Members of four arachnid orders, thirteen insect orders, and five other invertebrategroups (Isopoda, Diplopoda, Chilopoda, Oligochaetes, Mollusca) were taken in pitfallsamples. Figure 13 shows a summary of the data from pitfall trapping at the six sites.

Figure 13. Summary of pitfall data for one floodplain, and five forest sites.

Site No. RTUs No. of Individuals α d

Floodplain 80 485 55.24 0.329FT1 88 655 27.36 0.357FT2 88 368 36.64 0.215FT3 95 493 35.01 0.215FT4 109 649 37.49 0.236FT5 75 274 34.06 0.157

Pitfall trap assemblages at most sites were relatively large, although not reaching 1000individuals, which Magurran (1988), recommends as a level beyond which α isunaffected by a change in sample size. Values for the indices calculated are morereliable for the pitfall than the sweep-net data. These reveal a higher level of diversityon the floodplain site (open grassland and scrub) than at any of the forest areas.However, there appear to be no consistent differences in levels of diversity betweenprimary and secondary forest sites. Most sites show a fairly high level of dominance

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 25

by a single taxa; this is particularly striking in the case of the floodplain site, as thisalso has a high α diversity.

The composition of the assemblage collected in pitfall traps varied greatly betweensites. Figure 14 shows the proportion of the total number of individuals in eachassemblage which each major invertebrate group contributed.

Figure 14. Percentage of the total number of individuals at each site in majorinvertebrate groups.

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

FT5

FT4

FT3

FT2

FT1

site1 others

Aranae

Collembola

Thysanura

Diptera

Orthoptera

Hemiptera

Hymenoptera

Coleoptera

5.4 Discussion

5.4.1 Insects of the herb layers

Diversity values (as measured by α) of samples taken by sweep-net were highest inthe primary forest locations. Although it is often suggested that forests should show agreater diversity of invertebrate fauna than open sites (Janzen, 1973), previous sweep-net studies (for example, Janzen, 1973; Hill & Kemp, 1996) have often shown thatdisturbed forests have a greater diversity than do primary forests. The deep shade ofprimary forest areas tends to restrict the development of ground vegetation, thestratum sampled by sweeping. At Ba Be National Park in 1994 (Kemp et al., 1994),the highest values of α were recorded in secondary bamboo forest.

The 'primary' forest sites sampled in the current survey were not entirely undisturbed,and had a more developed ground vegetation than the more disturbed sites (seeChapter 4). Plant and insect diversity tends to be positively correlated (Spitzer et al.,1987), and sites with a more diverse ground vegetation would be expected to have agreater diversity of insect life. However, all of the samples were small; much largerinsect assemblages need to be sampled before such conclusions could be made.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 26

5.4.1 Ground-dwelling insects

The terrestrial invertebrates sampled by pitfall trapping might be expected to be lessstrongly influenced by the plant diversity of the study site than those invertebratesamples taken by sweep-netting, where the vegetation is directly sampled. Therefore,although the flora of the grassland site was dominated by a few herbaceous species(mostly Poaceae), it showed the highest diversity of ground insects, as sampled bypitfall trapping.

One factor influencing the apparent diversity at the open floodplain site could be thepattern of insect movement over open ground. Highly mobile terrestrial invertebrates(such as the ground beetles, Carabidae) tend to move more rapidly over bare groundthan in sheltered situations (Greenslade, 1964); therefore, they are more likely to beintercepted in pitfall traps. It is likely that the shade and shelter offered by forest(secondary or primary) influences invertebrate movement to a great extent, so thatvalues of diversity indices from the open site and forested sites cannot be directlycompared.

The fauna of the open site was dominated by the Collembola (springtails); theOrthoptera (grasshoppers and crickets) also made up a significant part of theassemblage at this site. Spitzer et al. (1993), working on butterflies, found that thespecies of ruderal, open habitats tended to have a greater range (and, therefore, weremore common) than the species characteristic of forests, and it is probable that themost abundant invertebrate species at the open floodplain site are widely distributedand common. In the forest sites, Collembola made up a smaller proportion of thefauna sampled. Orthoptera were always a minor component of these assemblages. Incontrast, the Coleoptera (beetles) and Hymenoptera (particularly the ants) were amajor part of these samples. The Aranae (spiders) never made up a large part of theassemblage, in terms of the number of individuals present; however, this group washighly diverse in all the samples, represented by few individuals of many taxa.

Differences between the faunas of varying forest types do not appear to follow apredictable pattern, but the limited ecological information which can be conveyedusing RTUs may in part be responsible for this finding. A far larger number ofsamples from different forest types would be necessary before any underlying trendscould be observed, especially since the results of such studies are complicated by themobility of invertebrate species.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 27

6.0 BUTTERFLIES (Lepidoptera, Papilionoidea)

6.1 Introduction

Butterflies are often considered important indicators of overall biodiversity(Government of SRV, 1994). In biodiversity surveys of less well-studied tropicalenvironments (such as Vietnam's forests), work on most insect groups is hampered bythe sheer diversity of insect life, and the lack of reference works for theiridentification (Spitzer et al., 1993). However, there are a number of identificationworks for the butterflies of South-East Asia (for example, Corbet & Pendlebury,1956; Pinratana, 1977-88; Lekagul et al., 1977). While butterfly diversity can be high,it is usually possible to make a representative collection in a survey area over a periodof weeks, although some species are short-lived and seasonal as adults, and a fullcollection will probably regular collection over at least one year (A. Monastyrskii,pers. comm.).

Because the Lepidoptera of Vietnam have received little scientific attention in thepast, all data gathered on butterfly distribution and ecology is valuable. Several newspecies have recently been described from specimens collected by SEE in NorthVietnam (Devyatkin, 1996).

6.2 Methods

Three methods were used in order to establish a species list for Ba Be, and investigatehabitat preferences and change in butterfly populations over the study period:

1) Butterfly transects2) Opportunistic collection3) Butterfly trapping

6.2.1 Butterfly transects

Transect methods, adapted from those developed in the UK by Pollard (1975, 1977),were used to investigate characteristics of the butterfly communities in differenthabitats, and changes over time. Three transects were established, each one kilometerlong. Each of the transects was walked once a week, at 1000hrs. On each occasion,one observer recorded all the butterflies entering a 10m x 10m x 10m area whilewalking at a slow, constant pace along the 1km transect path. Unknown or newspecies were collected by hand net, for later identification.

6.2.2 Opportunistic collection

Butterflies were collected throughout the study area, in as wide a variety of habitats aspossible, throughout the study period.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 28

6.2.3 Butterfly trapping

Butterfly traps, as described by Austin & Riley (1995) were set up near the basecamp, in trees close to the Ba Be lake. Ripe banana was used as bait. The traps werechecked regularly and unwanted insects released.

6.3 Results

6.3.1 Species-richness

Overall, a total of 167 species of butterfly were collected at Ba Be (see Appendix 4).Eleven butterfly families were represented in the collection. Figure 15 shows thedistribution of butterfly species between families.

Figure 15. Pie chart showing distribution of butterfly species between families

Papilionidae

Pieridae

Danaiidae

Amathusiidae

Satyridae

RiodinidaeNymphalidae

Libytheidae

Lycaenidae

Hesperiidae

Acraeidae

6.3.2 Butterfly communities in different habitats

The three butterfly transects carried out were in the following habitats and locations;

1) Butterfly Transect 1. Open grassland, beside River Nang. 175m asl.2) Butterfly Transect 2. Secondary forest (dominated by Streblus tonkinensis) onlimestone outcrop beside the R. Nang. 180m asl.3) Butterfly Transect 3. Less disturbed secondary forest, near Nam Giai village(remote from the river or lakeside). Dominated by Streblus tonkinensis. 750m asl.

Each transect was carried out seven times over the survey period.

Species present in each transect site are marked with an asterisk in Appendix 4.

Summary statistics for each transect are shown in Figure 16.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 29

Figure 16. Summary statistics for butterfly transects.

Total no.Individuals

No. Species α d

BT1 1135 62 14.076 0.242BT2 870 72 18.630 0.286BT3 125 41 21.264 0.080

The composition of the butterfly community at each site varied greatly. Figure 17shows the proportion of the total numbers of individuals at each site, in the mainbutterfly families. The families Lycaenidae and Hesperiidae are excluded, as these arethe most difficult to recognise on sight (Spitzer et al., 1993), and were probablyunder-recorded.

Figure 17. Proportion of the total number of individuals in each family (excludingLycaenidae and Hesperiidae).

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

BT3

BT2

BT1Papilionidae

Pieridae

Danaiidae

Amathusiidae

Satyridae

Riodinidae

Nymphalidae

6.4 Discussion

6.4.1 Species-richness

The butterfly fauna of Ba Be is extremely species-rich in comparison to other forestreserves in northern Vietnam; at Na Hang Nature Reserve, Tuyen Quang province, atotal of 142 species were recorded in the course of six months survey work (Hill &Hallam, 1997); at Tam Dao National Park, 117 species (excluding Hesperiidae andLycaenidae) were taken by Spitzer et al. (1993), over two months. This species-richness may be explained by the diversity of habitats at Ba Be, which range fromrelatively undisturbed forest to anthropogenic habitats around the lake itself.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 30

6.4.2 Species of interest

Several of the species collected are endemic or rarely collected in North Vietnam.Mandarina regalis (Satyridae), is endemic to North Indochina and the easternHimalayas. At Tam Dao National Park it is confined to undisturbed montane forest(Leps & Spitzer, 1990).The satyrids Zipoetis unipupillata and Ypthima similis were recorded for the first timein Vietnam in Na Hang Nature Reserve in 1996 (Hill & Hallam, 1997).

6.4.3 Butterfly communities in different habitats

Butterfly diversity (as measured by Fisher's α) was highest in the forest site, FT3. Inprevious studies (Spitzer et al., 1993; Hill & Hallam, 1997), open and ruderal habitatsdisplay a greater diversity of butterfly species than forest sites. However, at Ba Be thediversity index α was low for BT1 (grassland), because the butterfly community atthis site was heavily dominated by a few very abundant species.

The greatest number of species was observed at BT2, probably because this transecthad elements of both the open-ground fauna of BT1 (the adjacent river acted as aflypath for open-ground species, and occasional breaks in the canopy allowedherbaceous plants to flourish, providing a nectar source), in addition to the forestfauna. As at BT1, the dominance of a small number of species meant that the diversitycalculated was relatively low. This result contrasts with the findings of Spitzer et al.(1993) at Tam Dao National Park, where forest communities of butterflies were morelikely than ruderal communities to be dominated by a single abundant species. Thisresult may be influenced by the period of study; many forest species appear to bestrongly seasonal in occurrence, with adults flying in the summer wet season (Spitzeret al., 1993).

The butterfly community of the open site (BT1) was dominated by the familiesPieridae (especially Appias spp. and Eurema spp.) and Nymphalidae (especiallyJunonia spp.)(see Figure 16).

At the forest site BT2, the Amathusiidae, a family of large forest butterflies, wasrepresented by five species (although no amathusiids were present at BT3).At BT3, the Satyridae formed an important part of the fauna (especially Melanitisphedima and Mycalesis spp.), although no individual species was dominant as intransects BT1 and BT2.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 31

7.0 BIRDS

7.1 Introduction

Vietnam has a diverse avian fauna, including a high proportion of endemic taxa. Themost recent and extensive catalogue of the birds, Checklist of the birds of Vietnam(Vo Quy & Nguyen Cu, 1995) includes 828 species, and there are certainly speciespresent in Vietnam which are not included in this list. Three 'Endemic Bird Areas', ofparticular importance to the conservation of endemic bird species, have beenidentified (ICBP, 1992); all are in central and southern Vietnam. However, the HoangLien Son mountain range (in northern Vietnam) supports an important range ofendemic subspecies.

Although the birds of Vietnam have been studied since the early part of this century(Delacour & Jabouille, 1931), and are amongst the most well-documented elements ofthe fauna, knowledge of bird distribution and ecology are incomplete, and new taxaare still being described (Eames et al., 1994).

The SEE-Vietnam programme aims to increase this knowledge of the bird fauna byproducing inventories of species (with a measure of relative abundance) for each sitestudied, providing information on seasonal variation and habitat preferences of birds.

The specific objectives of this survey were:

• To create an inventory of all bird species identified;• To ascertain relative abundances of each bird species present;• To determine seasonal differences between this and the previous survey at Ba Be National Park (due to the appearance of winter migrants);• To collect additional information on bird ecology and habitats.

7.2 Methods

The bird survey was conducted throughout the study period, at all times of day (withan emphasis on time periods soon after dawn and before dusk) and in all weatherconditions.

Observers used binoculars, and recorded field notes were using a portable taperecorder or notebooks. Data were recorded on date, time, habitat and numericalabundance, as well as any other interesting characteristics (i.e. winter and juvenileplumages, and behaviour).

Identification was carried out using the field guides Guide to the Birds of Thailand(Lekagul & Round 1991), Birds of S.E. Asia (King et al. 1975), and Birds of HongKong and South China (Viney et al. 1994). Bird species positively identified werelisted in accordance with An annotated checklist of the birds of the Oriental region(Inskipp et al., 1996).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 32

7.3 Results

Approximately 600 hours were spent in bird observation, in addition to observationswhilst in the field carrying out other research.

Although an effort was made to carry out survey work in all habitats represented inthe reserve, observation effort was inevitably concentrated in the area to the North ofthe lake and in waterside habitats, which were the most frequently visited.

The number of different species sighted was 189. The complete list is shown inAppendix 5, which also gives data on typical habitat, frequency of occurence, andnotes of interest for each species.

In 1994, a list of 111 species was produced for Ba Be National Park (Kemp et al.,1994). The earlier list includes 25 species not recorded in the current study (Appendix5c), increasing the list for Ba Be to 214 species. Some of the interesting records arediscussed below.

7.4 Discussion

The total list of 214 bird species for Ba Be is comparable to other highly diverse sitesin Vietnam, such as Sa Pa, Lao Cai province (where 208 species have been identified;Kemp et al., 1995), and the Na Hang Nature Reserve, Tuyen Quang province. In thelatter reserve, approximately 30km from Ba Be, 221 species were observed in twosurvey periods (Hill & Hallam, 1997). However, the bird fauna at Ba Be and Na Hangdiffers, because a range of aquatic habitats unrepresented at Na Hang are important atBa Be. While only three kingfishers were observed at Na Hang, seven were present atBa Be. Na Hang had only one member of the family Charadriidae (Plovers), Ba Besix.

It is possible that one of the species recorded in the earlier survey at Ba Be (Kemp etal., 1995), the Limestone Wren Babbler (Napothera crispifrons), was erroneouslyidentified. While it was not seen during the 1996 study, the similar large N Vietnam-NE Laos race (King et al., 1975) of the Streaked Wren Babbler (Napotherabrevicaudata) was seen. The latter species was also recorded at Na Hang NatureReserve in 1996 (Hill & Kemp, 1996; Hill & Hallam, 1997). The Limestone WrenBabbler has been recorded at Cuc Phuong National Park, North Annam (Robson etal., 1989), and its range in Vietnam is given as 'N Annam and W Tonkin' by King etal. (1975). The two species are easily confused and generally differentiated by theircalls (J. Eames, pers. comm.).

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 33

7.4.1 Range extensions

Three of the species identified at Ba Be were outside their known ranges in Vietnam,as described in Checklist of the Birds of Vietnam (Vo Quy & Nguyen Cu, 1995).However, although not previously recorded in North-East Vietnam, all are knownform the adjacent North-West region.

7.4.2 Altitude reductions

Thirteen of the species recorded were outside the typical altitude ranges given in Birdsof South-East Asia (King et al., 1975). These are shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18. Bird species observed outside their usual altitude range.

English name Scientific name Altitudes given inKing et al., 1975

Altitude inBa Be

Maroon Oriole Oriolus traillii 610-2,133m 350mShort-billed Minivet Pericrocotus brevirostris 914-2,133m 750mSmall Niltava Niltava macgrigoriae > 914m # 620mFujian Niltava Niltava davidi > 914m 180mWhite-tailed Flycatcher Cyornis concreta > 914m 700mWhite-tailed Robin Myiomela leucura 1,067-2,133m 750mPallas' Leaf Warbler Phylloscopus proregulus > 1,524m 180mGrey-cheeked Warbler Seicercus poliogenys > 1,220m 750mPygmy Wren Babbler Pnoepyga pusilla > 1,067m 180mGolden Babbler Stachyris chrysea > 914m 750mSilver-eared Mesia Leiothrix argentauris > 914m 175mStriated Yuhina Yuhina castaniceps 610-1,830m 180mStreaked Spiderhunter Arachnothera magna > 914m 750m

# = sometimes lower in winter.

Several of the species were significantly below their expected altitude ranges. Fivespecies; Small Niltava, Fujian Niltava, White-tailed Flycatcher, Silver-eared Mesia,and Streaked Spiderhunter have been recorded previously at low altitudes at Na HangNature Reserve, North Vietnam (Hill & Kemp, 1996; Hill & Hallam, 1997), wheresurveys were carried out in the late winter and summer (rainy season). The repeateddiscovery of these species outside their expected altitude range suggests that theymight be normally resident at low altitudes in Vietnam.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 34

7.4.3 Rare species

Two of the bird species recorded (the Crested Kingfisher and Long-tailed Broadbill)are listed as threatened species in the Vietnam Red Data Book (RDB, 1992). A totalof eight other species (see Appendix 5) are regarded as 'Near-Threatened' on aninternational scale; that is, they are close to the threatened categories used by IUCN toclassify species in danger of extinction (Collar et al., 1994). Neither the CrestedKingfisher nor the Long-tailed Broadbill is regarded as near-threatened or threatenedat the world level.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 35

8.0 MAMMALS

8.1 Introduction

The mammals are one of the better-known faunal groups of Vietnam. A total of 223species were listed in a checklist and atlas of Vietnamese mammals published in 1994(Dang Huy Huynh et al., 1994), although the distribution data given is incomplete andoften outdated; several of the species listed (including Tapirus indicus, Dicerorrhinussumatrensis, and Cervus eldi) have probably already become extinct in Vietnam(Government of SRV, 1994). The distribution and status of small terrestrial mammalsand bats are particularly poorly known.

The aim of the mammal survey work carried out by SEE is to produce an inventory ofspecies for each site visited, to supplement data on forest reserves that is ofteninaccurate and outdated.

8.2 Methods

Three methods were used in the mammal survey;

• Mammal trapping (for small mammals, especially Muridae);• Bat-netting at cave roosts and at feeding grounds;• General observation of large mammals, their tracks and signs.

Detailed methodologies are given below.

8.2.1 Mammal trapping

Mammal trapping was carried out in a variety of vegetation types throughout theNational Park.

At each site, a trapline of 10 Vietnamese live traps was set out for four nights. Thetraps were spaced at intervals of 7-10m and baited with ripe fruit. Trap-lines werechecked every day, and for all trapped animals, the following details were noted;species, sex, age, weight, and measurements (Head/body, Tail, Hindfoot and Ear).Specimens were marked by toe-clipping and released. Some specimens were killed asreference material for later taxonomic confirmation.

8.2.2 Bat netting

Bat netting was carried out at cave roosting sites, and feeding grounds within theforest and on open ground beside water bodies. In each location, up to five mist netswere used, placed within caves or spanning aerial pathways used by bats. The netswere checked regularly throughout the period of netting, and bats removed.Measurements were taken of forearm, fingers, ear, thumb, foot and body lengths. Onespecimen of each species caught was killed using ether, and preserved for reference.

Ba Be National Park 1997

Frontier-Vietnam Environment Research Report 10 36

Bats were identified using Mammals of Thailand (Lekagul & McNeeley, 1971) andMammals of the IndoMalayan region (Corbet & Hill, 1992).

8.2.3 Mammal observation

Mammal observation was carried out throughout the period of study, usually inconjunction with bird observation. Methods used were similar to those for the birdsurvey, with observation conducted while moving quietly through the forest or from astationary hide. In addition, mammal tracks and signs, and remains (bones) wereidentified where possible. Mammals were identified using Mammals of Thailand(Lekagul & McNeeley, 1971), Preliminary identification manual for the mammals ofSouth Vietnam (Van Peenen, 1969), and Mammals of the Indomalayan Region (Corbet& Hill, 1992).

8.3 Results

8.3.1 Mammal trapping

Mammal trapping was carried out at seven sites within the park; four of the fivevegetation transects (except FT3), and, in addition, two sites to the North of the campnear FT3, and another close to FT2, all in secondary forest (see map, Figure 4). Attwo sites (both of the sites to the North of the camp), the trapping process wasrepeated after 20 and 30 days, in order to study the movement of the mammals byrecapture.

In total, 547 trap/nights were carried out. During this time, 72 specimens of sixspecies (three rodents, three insectivores) were collected (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Results of small-mammal trapping