ART & DESIGN Why Richard Avedon’s Work Has Never Been More Relevant The photographer’s social conscience, revealed in a show at Pace/MacGill and a new edition of “Nothing Personal,” deepens his enduring legacy. By PHILIP GEFTER | NOV. 13, 2017 “William Casby, Born in Slavery, Algiers, Louisiana” (1963), one of many portraits in Richard Avedon’s “Nothing Personal,” a book he worked on with James Baldwin. Credit Richard Avedon

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

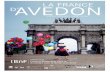

ART & DESIGN

Why Richard Avedon’s Work Has Never

Been More Relevant

The photographer’s social conscience, revealed in a show at Pace/MacGill and a new edition of

“Nothing Personal,” deepens his enduring legacy.

By PHILIP GEFTER | NOV. 13, 2017

“William Casby, Born in Slavery, Algiers, Louisiana” (1963), one of many portraits in Richard Avedon’s “Nothing

Personal,” a book he worked on with James Baldwin. Credit Richard Avedon

In 1964, Richard Avedon published “Nothing Personal,” a lavish coffee table book with gravure-printed portraits of individuals who do not fit into any single classification: Allen Ginsberg standing naked in a Buddhist pose opposite George Lincoln Rockwell, the founder of the American Nazi Party; the puffy-eyed Dorothy Parker, her bags containing a lifetime of tears, side by side with a sullen and deflated, if still-shimmering, Marilyn Monroe; a young and earnest Julian Bond among members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; and the grizzled William Casby, who had been born into slavery about 100 years earlier. “Nothing Personal” was published only months after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, in the period of profound cultural soul-searching following President Kennedy’s assassination. Despite Avedon’s glamorous reputation, it was his social conscience — revealed in the range of photographs in this book — that may be the surprise that deepens his enduring legacy. On Nov. 17, the first comprehensive presentation of material from “Nothing Personal” will be on view at Pace/MacGill Gallery in Chelsea, through Jan. 13; concurrently, Taschen is releasing a new edition of the book, with the original essay by James Baldwin — and a new one by Hilton Als. “It isn’t like a simple Disney melody,” Peter MacGill, the president of Pace/MacGill, said in a telephone interview about ‘‘Nothing Personal.’’ “Avedon and Baldwin cared deeply about America.” Mr. MacGill believes Avedon’s work has never been more relevant because “the ’60s were an explosive time, and we are in an explosive time today.” Avedon collaborated with Baldwin, his old high school friend, who wrote a cri de coeur of astonishing eloquence about the absence of common dignity in America, denouncing the false myths and damaging racial and ethnic hierarchies, and, ultimately, abjectly, pointing to the deep and abiding loneliness that underlies the glossy veneer of American optimism put forward by Hollywood and the media.

“Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Headed by Julian Bond, Atlanta, Georgia” (1963), from Richard Avedon’s book “Nothing Personal,” portraits from which are on display at Pace/MacGill Gallery starting Nov.

17. Credit Richard Avedon

Baldwin’s essay begins with a withering description of the television ads he is forced to endure while watching the news — ads that aim to sanitize, brighten, straighten, tame and tweak the skin, hair, teeth and bodies of viewers into an impossible standard of perfection that positions the enemy to be, well, nature itself. The portraits in “Nothing Personal” present a stark yet authentic counterpoint to the American image of eternal youth and anodyne good cheer. The book’s most resonant chords hover at a frequency detected in the balance of Avedon’s austere minimalism and Baldwin’s mournful jeremiad. Only one portrait in “Nothing Personal” bears a date: “Maj. Claude Eatherly, Pilot at Hiroshima, August 6, 1945.” It refers not to when the photograph was made but to when Major Eatherly flew weather reconnaissance over Hiroshima and then gave the O.K. to drop the first atomic bomb, code-named “Little Boy.” Avedon first contacted Eatherly to photograph him in early 1963. “For a long, long time I have felt a connection with you, as have my wife and many of my friends,” Avedon wrote to him in Galveston, Tex., “because what happened to you is almost like a metaphor of what many Americans feel has happened to them.” Avedon flew to Galveston to make his tightly cropped portrait of Eatherly, brow furrowed and hand cupped over his eye as if to scrutinize the distant horizon.

“Major Claude Eartherly, Pilot at Hiroshima, August 6, 1945” (1963), from Richard Avedon’s book “Nothing Personal,” which will be reissued in early December. Credit Richard Avedon

In a series of museum talks, Colin Westerbeck, the eminent photography historian, argued that Major Eatherly is the central portrait in “Nothing Personal,” perhaps even in Avedon’s entire career. He pointed out the absence of shadow and the blown-out background in Avedon’s portraiture that left “every wrinkle, stubble, wen and nervous tick” on his subjects faces strikingly visible. “When that bank of strobes went off in Avedon’s studio — pfoom! — subjects must have felt as if they’d been caught in an atomic bomb blast,” Mr. Westerbeck said. That “bomb blast” became the signature style with which Avedon went on to create many series of photographs, including “The Family,” 69 portraits of the most powerful and influential Americans in 1976, published in Rolling Stone for the country’s bicentennial. His 1985 book, “In the American West,” consists of portraits of anonymous workers, drifters, cowboys and random citizens made throughout the Western United States over five years, a contrast to the pantheon of accomplishment and celebrity that characterized most of Avedon’s portraiture.

In conceiving “Nothing Personal,” Avedon might have had in mind a dialogue with “The Americans,” by Robert Frank, published five years earlier — an artist’s book that struck a sober note about the story America told itself versus the realities of daily life for its citizens. At the time, “The Americans” was little known outside of New York art circles, but the book had a profound influence on photographers — including Avedon — and on the direction of photography itself. While Mr. Frank had traveled across the country to capture happened-upon moments in ordinary life, Avedon’s idiom was the portrait, with which he was equally intent on telling a deeper truth about America. Implicit in Avedon’s version was the persistent threat to our existence, something the Cuban missile crisis had brought that much closer two years before “Nothing Personal” was published. At the time, Avedon considered the portraits in the book to be “some of my very best work.”

“Allen Ginsberg, Poet” (1963), by Richard Avedon. Credit Richard Avedon

Yet, to his surprise and chagrin, the public reaction was swift and hostile. Writing in The New York Review of Books, Robert Brustein lashed out at the book’s extravagant “snow-white covers with sterling silver titles” before excoriating the effort in his critique. (It predated by six years Tom Wolfe’s incendiary 1970 essay, “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” in New York magazine — a savage takedown of New York’s intellectual circle of “limousine liberals” as conspicuous hypocrites.) “‘Nothing Personal’ pretends to be a ruthless indictment of contemporary America,” Brustein wrote, “but the people likely to buy this extravagant volume are the subscribers to fashion magazines, while the moralistic authors of the work are themselves pretty fashionable, affluent, and chic.” Truman Capote came to Avedon’s defense in a letter to the editors published the following month: “Would he rather it was printed on paper-toweling?” Capote asked. “Brustein accuses Avedon of distorting reality. But can one say what is reality in art? — ‘An artist,’ to repeat Picasso, ‘paints not what he sees, but what he thinks about what he sees.’ This applies to photography — provided the photographer is an artist, and Avedon is.” The year before “Nothing Personal” was published, Avedon had traveled to the South to photograph leaders of the civil rights movement, among them Martin Luther King Jr., as well as those who staunchly opposed it, such as Gov. George Wallace, of Alabama. When he returned to New York, he opened his studio to photographers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (S.N.C.C.) to train them to shoot rallies and sit-ins in a photojournalistic style that the mainstream press would publish. He convinced Marty Forscher, the owner of Professional Camera Repair Service, to donate 75 cameras and a supply of film to the S.N.C.C. for three years. In 1965, Visual Arts Gallery, where Avedon was a board member, mounted a show of S.N.C.C. photographers’ work.

“Joe Louis, Fighter” (1963), by Richard Avedon. Credit Richard Avedon

At DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, Avedon, who was Jewish, and Baldwin, who was African-American, were editors of “The Magpie,” the school’s literary magazine. They conceived a project with text and photographs called “Harlem Doorways” that never fully got off the ground. In later years, Avedon recounted the time as students when Baldwin came to visit him at home on East 86th Street, and the doorman made him use the service elevator. Avedon’s mother was furious and summoned the doorman upstairs to apologize to young Baldwin for the insult. Can Avedon’s illustrious image coexist with evidence of his social conscience? It is found throughout his work and in the causes he championed, both publicly and privately. In 1955, he photographed Marian Anderson, who was performing in Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera,” the first African-American soloist to sing on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera. In the portrait, her mouth is rounded into an oval so expressive that you can almost hear her voice — an unusual feat of visual onomatopoeia. The portrait ran in Harper’s Bazaar and Avedon considered its publication his own small stand against racial discrimination.

In 1959, when Avedon first photographed China Machado, a Chinese-born, Portuguese-American fashion model — encouraged by Diana Vreeland, the fashion editor of Bazaar — the magazine’s publisher said: “Listen, we can’t publish these pictures. The girl is not white.” Avedon was so angry that he threatened to leave Bazaar. The pictures were published.

Richard Avedon photographing S.N.C.C. demonstrators in 1963. Credit The Richard Avedon Foundation

As the guest editor of the April 1965 issue of Bazaar, Avedon included his own pictures of Donyale Luna, the first African-American model to appear in the magazine, and endured the wrath of William Randolph Hearst, the publisher, when advertisers pulled out of the magazine. “For reasons of racial prejudice and the economics of the fashion business,” Avedon said, he never photographed her for editorial use again. In 1967, hired by McCann Erikson, the advertising agency, to work on a Coca-Cola campaign, he chose an African-American high school teacher as its focus. While only tiny dents in racism’s hardy shell, for Avedon, a first-generation immigrant who endured anti-Semitism throughout his childhood in New York City, each editorial milestone felt like a groundbreaking moral victory. Avedon had numerous museum exhibitions during his lifetime, yet the art world was slow to accept him. Because he had become the world’s foremost fashion photographer early in his career, his name carried the taint of commerce and critics too often dismissed these portraits as “stylized.” Stylization was never what he was after.

Instead, he gave all his subjects equal stature, shooting each one with strobe lighting against a white background — specimens of the species that could annihilate itself at any moment. Avedon instinctively understood the threat to our existence posed by “Little Boy” at Hiroshima; his stone-cold, corpselike representation of individuals in the second half of the 20th century remains the existential register of his portraiture. “Strangely,” he wrote in his letter to Eatherly, “just as your experience, although in a way too horrible to be borne, made you see that we are all part of one another, the fact of you does the same for us.” - Philip Gefter is writing a biography of Richard Avedon.

http://nyti.ms/2AGyeQy

Related Documents