Arancini: a Contested Symbol of Sicilian Identity Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Enzo Zaccardelli, BA Graduate Program in Anthropology The Ohio State University 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Jeffrey H. Cohen, Advisor Dr. Dana Renga Dr. Robert Cook

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Arancini: a Contested Symbol of Sicilian Identity

Master’s Thesis

Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for

the Degree Master of Arts,

in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University

By

Enzo Zaccardelli, BA

Graduate Program in Anthropology

The Ohio State University

2020

Thesis Committee:

Dr. Jeffrey H. Cohen, Advisor

Dr. Dana Renga

Dr. Robert Cook

Abstract

This paper looks at how opposing groups of pro-migrant and nationalist Sicilians contest

the meaning of arancini, a food emblematic of the island, and Sicilian identity in general after the

arrival of a migrant ship from North Africa in August of 2018. I analyze how the groups interpret

their history and what it means to be Sicilian differently and how that affects migrant reception

today.

ii

Dedication

Dedicated to Dr. Jeffrey H. Cohen who has mentored me and who has helped me every step

along the way, and, of course, my parents, who have always been there for me and continue to

support me.

iii

Vita

Personal Information

The Ohio State University 2018-present

Cleveland State University 2016-2018

Cuyahoga Community College 2014-2016

Fieldwork on Refugee and Migrant Integration in Calabria, Italy 2018-present

Ethnographer at The PAST Foundation 2018

Independent Study on Refugee Integration and Stress Coping Mechanisms 2016

Publications

Zaccardelli, Enzo. (2018). “Review of They Leave their Kidneys in the Fields: Illness, Injury,

and Illegality among US Farmworkers, by Sarah Bronwen Horton. Critique of

Anthropology.

Zaccardelli, Enzo. (2015). “If the Deceased Could Speak, Part II: The Cycle of Genocide,” Breakwall

6: 13-16.

Fields of Study

Major Field: Anthropology

iv

Table of Contents

Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….ii

Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….iii

Vita………………………………………………………………………………………iv

List of Illustrations………………………………………………………………………vi

List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………vii

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………...1

Data Sources…………………………………………………………………………….3

Setting …………………………………………………………………………………..5

But Why Arancini?: The Historical and Symbolic Meanings…………………………..10

Discussion………………………………………………………………………………17

Arancini in the Anthropological Imagination…………………………………………..24

Conclusion.……………………………………………………………………………..30

Appendix A. Arancini Recipe…………………………………………………………..32

Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………35

v

List of Illustrations

Illustration 1. Sicilian Iconography……………………………………………………….12

Illustration 2. Protestor’s sign reads “Catania Welcomes” ……………………………….14

vi

Introduction

In August 2018, the Italian government refused to allow 200 migrants stuck on board the

Diciotti to disembark in Catania, a Sicilian port city. Greeting the boat were pro-migrant and na-

tionalist Sicilians. The pro-migrant group carried arancini, a traditional Sicilian food and a sym-

bol of Sicilian hospitality. Nationalists contested the use of arancini to symbolically welcome 1

the refugees and show solidarity with migrants.

Migrant supporters presented arancini as the Sicilian way of welcoming foreigners, dis-

playing both hospitality and solidarity. In the process, arancini become “a symbol of sharing for

our city,” a “symbol of inclusivity, welcome and assistance” uniting both sides of the Mediter-

ranean (D’Ignotti 2019). Nationalist counter-protestors would portray arancini as a symbol of

Sicilian/Italian culture and cuisine but limited its value as a symbol of hospitality and welcome,

at least for outsiders. Instead, nationalists would use arancini to represent a uniquely Sicilian

identity, which must be safe-guarded from the Other, and a representation of the Italian State and

define the migrants as strangers by refusing to offer them arancini and by rejecting/acknowledg-

ing the origins.

The important role of arancini in the events surrounding the arrival of these African mi-

grants was a surprise given the food’s humble nature. Arancini are fried rice balls with various

fillings that originated in the Islamic era of Sicily, when North Africans controlled the island and

parts of the southern Italian peninsula. Arancini are a convenient, filling and nutritional food for

travelers and today, they are a treat for visitors to the Island. A symbol of Sicily and its history,

I use the spelling “Arancini” to refer to both plural and singular forms of the word and to avoid regional debates 1

over its spelling—people on opposite sides of the island argue over whether it should be spelled arancino [singular] and arancini [plural], or rather arancina [singular] and arancine [plural].

1

arancini are also symbols of mobility, liberty, and welcome. Emblematic of the island and

its people, these simple rice balls became a site for the debate and contest around culture, migra-

tion, and identity. In this paper, I focus on events surrounding the arrival of the Diciotti in August

2018 and demonstrate how arancini become central to debates between pro-migrant and national-

ist groups in Sicily. By looking at how symbols can be contested, we can better understand the

dynamics of group formation and identity, and how simultaneously increasing globalization, mi-

gration, and nationalism affect these. This case study also shows how within the larger debate

over Sicilian identity, there are smaller sub-debates between the two groups, which read their

shared history differently.

2

Data Sources

My research is rooted in the events of August 2018 in Catania, Sicily and what was de-

scribed as an ongoing crisis in migration as people fled unrest, violence, and discrimination in

their African homelands (Mainwaring 2019). The description of these acts and interviews of

those who participated come mostly from Italian newspapers and media outlets, some of which

have been translated into English for sources like the BBC. The interviews provide first-hand

evidence of what arancini means to Sicilians, and how pro-migrant supporters use arancini in

new, meaningful, and symbolic ways.

In addition to the news sources, ethnographic work in Sicily is crucial. In particular, I uti-

lize the research of Naor Ben-Yehoyada (2011, 2015, 2016, 2017). His ethnographic work pro-

vides insight into the historic migratory, economic, and social connections that link Sicily and

North Africa, and how these affect both of those areas today. These ethnographies offer invalu-

able, first-hand information and accounts as Sicilians describe arancini, themselves, their neigh-

bors and the African immigrants arriving to the island. Building upon anthropological research in

the region, I examine what Cohen and Sirkeci (2011) define as the “culture of migration,” or a

focus on the social patterns that surround mobility and settlement (also see Cohen 2004). Com-

bined, these approaches enable me to understand both micro- and macro-levels factors (from his-

tory to culture, identity to economics) that influence the symbolic meaning of arancini for migra-

tion supporters as well as nationalists.

Historical sources detail trade and migration over time and between the northern and

southern Mediterranean, as well as the origins of arancini. The histories of Sicily and arancini are

important to understand as they are being interpreted today and affect how Sicilians view them

3

selves and Others. In the appendices, I have included a recipe to show one type of arancini and

how contemporary arancini differs from those introduced in the past, which is important because

some Sicilians can point to the addition of pork as proof that arancini are strictly Sicilian, dis-

placing its Islamic, North African origins.

Finally, I rely on governmental records of the Italian State and Sicily to capture the

State’s position in the events of August 2018. Combined, these resources are crucial for under-

standing contemporary Sicilian identity. Building upon journalism, ethnography, history, migra-

tion studies and governmental records, I evaluate arancini as an active symbol and understand its

complex role in the construction and negotiation of Sicilian identity.

4

Setting

Arancini are a rich and complex symbol of Sicily and Sicilian culture. It is a food for

travelers and evokes a sense of liberty, exemplified in the case of Montalbano. Traditionally,

arancini are given to welcome the stranger or returning friend—another Sicilian. Tourists can

buy them, but that’s not hospitality, but rather a commercial venture. How arancini became such

a complex symbol is rooted in their history as well as contemporary events surrounding the ar-

rival of migrants to Catania. Sicily’s history is a story of historical connections throughout the

Mediterranean basin; and the island’s heritage is shaped by the people who arrived on its shores;

including the Greek, Carthaginians, Normans and Vandals, Byzantines, Arabs, Berbers, the

French, the Spaniards, Italians, and briefly in the 20th century, the Americans (Wright 2003).

Arancini are fried rice balls of varying sizes stuffed with a variety of ingredients. The

Arabs introduced many new ingredients and experimented with recipes. Arab chefs likely created

Arancini from a combination of the ingredients they brought as well as those ingredients brought

by earlier colonizers, and some scholars state that the various, diverse ingredients mirror the sto-

ry of Sicilian history itself (Wright 2003:380).

Arancini means “little oranges” in Italian, a fruit that the Arab Muslims who colonized

the island introduced. The term also derives from the Arabic word for oranges—naranj (Wright

2003:380). There are variations in spelling and ingredients spending on where in Sicily one re-

sides. Regardless of how it is shaped, spelled, or whether it includes cheese and/or meat or peas,

arancini are a symbol of Sicily and it is critical to both pro-migrant Sicilians and nationalists who

reject further immigration.

5

The two Sicilian groups interpret arancini and Sicilian culture differently, yet they are

reading the same histories. While pro-immigrant and nationalists debate the value of immigra-

tion, the agricultural and culinary contributions from the Arabs and Berbers to Sicilian foods and

cooking cannot be denied. Many of the foods that are fundamental to Sicilian cuisine—buck-

wheat, the grains used in pasta, various citrus fruits, couscous, dates and figs, sugar, rice, pista-

chio, saffron, spinach, and possibly ice cream and olives, among others—were introduced by

North African and Arab colonizers (Ruggeri 2018:401). Much of the foodstuffs were introduced

in the 10th century, and there are some recipes that have survived from the Islamic era of Sicily

and which first appeared in an 11th century cookbooks by Ibn Butlan, an Arab physician (Rug-

geri, 2018:402).

The arancini of today differ in many ways from those introduced by Arabs in the 10th

century. Originally sweet and filled with ricotta cheese, saffron and so forth, they are now filled

with tomatoes and can include pork (Ruggeri 2018:402). As the North African caliphate fell and

Sicily returned to control by other Christian, European powers, those nations’ cuisines were inte-

grated into the Sicilian palate, and the island reverted to Christianity, thereby allowing for pork—

an ingredient that would have been unfathomable in the Islamic era. The recipe for arancini al

burro, is included at the end of this paper.

Contemporary recipes, and especially those that use pork displace arancini’s Islamic ori-

gins. Nationalists can point to the recipes that include pork as proof that arancini is not connected

to Islamic north Africa. The arancini that they view as a localized symbol of their heritage is their

own and found only in Sicily. Pro-migrant groups are far more likely to point out

6

that there are numerous arancini recipes that do not include pork though, and the origins of

arancini do not change with the relatively recent addition of pork.

Migrations between the northern and southern Mediterranean is not new, nor is Sicily’s

relationship to the North African coast. Arancini originates from the ongoing history and interac-

tion of North African Arabs and Sicilians, through the late 1800s to the mid-1900s, and now

again with the contemporary movement of Africans and citizens of the Middle East into Italy. In

other words, migration in either direction is not new, nor is Sicily’s relationship with the North

African coast.

After Italian unification of the 1860s, virtually of the southern regions went into a period

of steep decline and were never able to match the economic and political power of the wealthier,

more industrialized North. While the scope and development of these differences in regions is

beyond the scope of this paper, what is important is the treatment and marginalization of south-

erners, particularly Sicilians, who responded, in part, by emigrating. Many emigrants went to the

Americas and North Africa, including an estimated 301,000 Italians who emigrated to Africa be-

tween 1876 to 1926 and settled primarily in Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia (Ratti

1931:449).

Sicilians have distrusted the Italian State’s government and have felt ignored and belit-

tled. Given Sicily’s marginalization, we might expect that Sicilians would feel sympathetic to-

wards other marginalized groups (Albahari 2008). In fact, the people of Lampedusa have voiced

their frustrations with the Italian government’s handling of migrants on the small island. Lampe-

dusa’s mayor stated, “Geographically we are much closer to Africa… for Italians we don’t exist!

They only notice us with the problem of the ‘illegals’. ‘Illegals’ so to speak, because they

7

are people like us… rights should be universal” (Giglioli 2016). Giglioli argues migrants' rights

are connected to natives’ rights on the islands because “they share the same experiences of mar-

ginalization" (2016).

The history of Arab Sicily extends well beyond the Islamic era of the island and precedes

the modern migration “crisis” as well. The pro-migrant camp acknowledges this history. Trade,

cultural exchanges, and history remain critical, and communities like Mazara del Vallo remain

closely linked to Africa’s Mediterranean coasts, and Tunisia in particular (Ben-Yehoyada 2011).

For more than a thousand years, trade, especially fishing and shipping-related trade, has connect-

ed the Island of Sicily to Tunisia and is evident in the presence of Arabic-based greetings and

foods (including arancini), among other aspects (Ben-Yehoyada 2011).

The 21st century has witnessed mass migration from North Africa, the Middle East, and

sub-Saharan Africa to Sicily, and more generally to Western Europe. In recent years, especially

following the Arab Spring in 2010, there has been a boom in migration occurring from North

Africa; while history can help explain why pro-migrant Sicilians felt a sense of solidarity with

the migrants seeking to disembark in Catania, the story is quite complicated and includes com-

peting voices—both pro-migrant and nationalist Sicilians. Despite belonging to the same imag-

ined community, the two groups of Sicilians hold oppositional viewpoints on what it means to be

Sicilian, what the nature of the immigrant is, and how best to respond to migration. The differ-

ence between pro-migrant and nationalist groups is especially perplexing considering the politi-

cal history of the current national government, which is led by a party that typically discriminates

against southern Italians and Sicilians and found its calling among Northern-separatists who

sought to split Italy to leave the South; some northern separatists’ newspapers

8

even called Sicilians and southern Italians “foreigners” and immigrants, demanding that they re-

turn home (Tambini 2012; Bullaro 2010; Dickie 1999; Garau 2014).

In fact, while the League (Lega) is weaker on the island than the mainland, it is picking

up support as its anti-migrant rhetoric appeals to supporters (Politico 2020; Albertazzi, Giovan-

nini, and Seddone 2018; Statista 2020; Richardson and Colombo 2013). Coming out of this com-

plex history and current political climate are arancini.

9

But Why Arancini?: Historic and Symbolic Meanings

Arancini are, and have been, a powerful and culturally significant symbol that is contest-

ed by pro-migrant and nationalist groups. Both groups agree arancini is important, but their ar-

guments are quite different. Pro-migrant supporters use arancini to welcome the Diciotti, while

nationalists focused on the challenges that migrants posed to the nation. In this section, I explore

the historical meaning of arancini for these two groups and illustrate how this important symbol

becomes emblematic of two very different positions.

Sicilians who support the government’s decision to prohibit the Diciotti from disembark-

ing have very different viewpoints on other issues but unite around the common goal of restrict-

ing immigration. As will be explained later, arancini also act as a symbol of unity within the two

groups of Sicilians.

Identity is one explanation for Sicilian nationalists rejecting immigration in support of the

Italian government. This explanation has several facets. First, globalization and the fear of being

“overrun” by outsiders may strengthen nation-states, empowering nationalism and, in this case,

drawing Sicilians closer to the rest of Italy by creating an imagined community. In other words,

Sicilians, who have traditionally kept their culture and heritage distinct from Italy and especially

the North, have begun to closer align themselves with other Italians to more clearly distinguish

themselves from the Non-European Other, a label which had previously been assigned to Sicil-

ians. Second, by aligning themselves more with the nation-state and excluding non-Europeans,

nationalist Sicilians are essentially gaining inclusion into the wider, more “privileged” Italian

community, elevating their socio-economic authority, at least temporarily. Food undoubtedly

plays a big role in Sicilian identity.

10

It is unsurprising then that food is a frequently used motif that reflects family life and

hospitality in many Sicilian and southern Italian literature. Arancini’s value is clear in the famed

Montalbano series, written by Andrea Camilleri, one of Italy’s most celebrated contemporary

writers. The story follows two brothers on the run from the law as they visit their mother who

prepares a feast of arancini. Together they celebrate their freedom and family as they consume

the arancini. A “symbol of liberty and home,” arancini are a comfort food for travelers—in the

case of Montalbano, the travelers are fugitives, but anyone can eat them, including migrants (Ri-

ley 2009). As with any symbol though, arancini are ambiguous and hold different meanings for

different people (Turner 1975:146). In Montalbano, arancini are prepared by the mother for her

fugitive sons and symbolize their newfound liberty and freedom. In a similar fashion, the pro-

migrant protestors welcomed the Diciotti with arancini, but the nationalists did not. The national-

ists likely viewed the migrants onboard the Diciotti as illegal criminals who might become a

burden and threaten local practices. They refused to offer the travelers arancini and by extension

any sort of hospitality, hoping to discourage their settlement in Catania.

Moreover, Arancini can be found at food stands and vendors on what feels like every

corner in Sicilian cities. Arancini are ubiquitous while walking the streets of Sicily, particularly

in tourist areas. It is common among the goods that fill storefronts that are characteristically “Si-

cilian” including Sicilian flags, “Moor head” statues and other monuments [see illustration 1].

11

Illustration 1: Sicilian Iconography; An example of cloths, pendants, etc. that are commonly sold on major Sicilian

streets. Various products are sold like this, though many are aimed at tourists and can distort Sicilian culture/identity.

The symbols indicate different important aspects emblematic of the island. Note arancini in the left corner.

The ubiquity of arancini remind us of its regionally-specific importance as a symbol of the is-

land. Yet, it is not enough to simply show that arancini is symbolic of the island. Arancini plays

12

numerous, sometimes contradictory roles in Sicilian life then because the different actors (like

the nationalist and pro-migrant groups) use it in varying ways.

What is important here is that there is a clash between the two Sicilians groups over the

meaning of arancini—they disagree over who can receive arancini and the purpose of giving the

food. One group sees arancini as connected to the historical heterogeneity of the island and its

international status. This group, defined as supporters of migrants and their rights, extended

arancini as a symbol of inclusion for outsiders. Nationalists on the other hand, keep the arancini

as a local symbol of what it is to be truly Sicilian. It does not include outsiders and limits the

recognition of the migrant as anything more than a dangerous stranger.

The protesters who supported the Diciotti migrants in August 2018 extended arancini as a

gesture of welcoming. In interviews with the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, organizers and

participants described arancini as “a symbol of sharing for our city” and “a symbol of inclusivi-

ty” as well as one of “welcome and assistance” (Ruta 2018). One protester stated more generally

that “food in Sicily has always been the way you welcome guests” (Ruta 2018). Some protestors

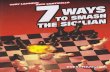

even brought signs depicting arancini that read “#Catania Welcomes” [see illustration 2; Rannard

2018], encouraging the debate to continue online—this is not just a one-time event but an ongo-

ing argument over the use and representation of arancini and Sicilian identity.

13

Illustration 2: Protestor’s sign reads “Catania Welcomes,” with an arancini depicted in the middle, and a hashtag to

encourage the debate to continue online. Courtesy of Rananrd 2018.

The signs that protesters wielded were symbolic and part of a symbolic performance (Turner

1975). The depiction of arancini on a sign served to, by its nature, symbolically welcome mi-

grants, to celebrate tolerance and to set a tone. Yet, no food changed hands and migrants were not

allowed to disembark. Arancini are signifiers, not gifts, since no material exchange occurred;

they represent a political and ideological position in relation to migration; and the position is not

set—rather it depends upon the group and the group’s stance on migration as well as their sense

of Sicily through time and in its current role as a port of entry for Africans and Middle Easterners

(Hoskins 2015:860).

14

Since no arancini were allowed on board the Dicotti, the display of solidarity and hospi-

tality by supporters became a purely symbolic act. No material exchange occurred. As another

protestor noted, “[Arancini] is also a symbol of unity between the two sides of the sea,” an inter-

esting claim that at least an acknowledged, shared history between Sicily and North Africa

(D’Ignoti 20019). Nevertheless, for the nationalists arancini were not a shared symbol of wel-

come. Nationalists certainly did not portray arancini as a symbol for unifying the northern and

southern Mediterranean. For this group, arancini is a symbol of Sicily and of what it means to be

Sicilian; it was not a welcome. While food is important in welcoming the guest, there is a clear

discrepancy in the symbolic importance of arancini between the two groups and a difference in

who is worthy of receiving arancini—or hospitality in general, per Derrida (D’Ignoti 2019; Der-

rida 2000).

The history of Sicily and its foods make this a more political, divisive issue that is debat-

ed around the interpretations of material culture and eating. Supporters offered arancini to travel-

ers in need as a part of their Sicilian culture. They acknowledged their historical solidarity

through a symbolic culinary exchange. Furthermore, arancini are a material representation of Si-

cilian hospitality that originates at home and extends to the community, nation, and beyond.

The nationalists, on the other hand, do not care to be reminded of the Arab origins of Si-

cilian foods. Even if history is important, arancini has undoubtedly changed a great deal since its

introduction in the 10th century. Sicilians and the nationalists protesting the arrival of the Dicotti

have made arancini their own and formed an even stronger sense of its value by adding

15

pork to the recipe, creating a division between Catholic (or non-Muslim) Sicilians and

Muslims from the southern and eastern Mediterranean.

The nationalists reassert their identity as Catholic Sicilians through local dietary customs

that contradict Islamic dietary laws. If a foreigner rejects the consumption of such an important

food, like a variation of arancini that uses pork, that foreigner is placed into the category of the

Other and can even be a threat due to this perceived non-conforming tendency (Comaroff and

Comaroff 1993). The very essence of what it means to be Sicilian-Christian is also contested

over food and migration, as explained below with the example of a Sicilian priest giving a ser-

mon onboard a migrant ship.

16

Discussion

I have shown how pro-migrant Sicilians interpret history and build upon that history to

welcome migrants to the Island and use arancini as a symbol of Sicilian hospitality, inclusion,

and mobility. The pro-migrant group transformed a local symbol of hospitality and mobility to a

welcoming symbol of hospitality and mobility because they recognize the island’s heterogenous,

international nature and, potentially, correlate the arancini with its North African origins. The

nationalists, as stated, oppose such migration and extension of their community to those outside

its borders. Perhaps the two groups differ in who is worthy of receiving this act of hospitality

(i.e. only other Sicilians, or also migrants from Africa and the Middle East) and, thus, who can be

included in their community, both symbolically and physically.

According to French intellectual Jaques Derrida, not all “arrivals are received as guests”;

there is a difference between a guest and a parasite, and it ultimately comes down to how the

hosts view the Outsider; the difference correlates with the two distinct camps of Sicilians. For

pro-migrant groups, they view the Outsider as a guest, someone deserving of hospitality (Derrida

2000:55). On the other hand, the nationalists view the migrants as parasites, or bad/unwanted

guests not deserving of the “benefit of the right to hospitality [or] asylum, [and] without this

right a new arrival can only be introduced…in the host’s home as a parasite, a guest who is

wrong, legitimate, clandestine, liable to expulsion or arrest” (Derrida 2000:55). This relates to

the hypothetical mentioned above with the hypothetical situation of nationalists and Montalbano.

A common argument by nationalists is that since the nation the migrants are arriving from is not

a full-out war zone, they are just opportunistic parasites feeding off of host countries, and don’t

need asylum; and even when they are indeed from active warzones, some people from the host

17

nation will claim that they are militaristic or should fight for their nation instead of migrating.

Thus, regardless of their reason for migrating, they’re not seen as deserving of guest status; there

is no such thing as a “good migrant” for these people. A lot of the perceived danger and rejection

of these migrants are due to differences in race, ethnicity, and religion.

Indeed, “In Western Europe, refugees are no longer perceived as honored guests deserv-

ing of consideration: They fall into the category of parasite; they have overstayed their welcome

and must be ushered out,” grouping all the Others together in a category inherently distinct from

Sicilians (Gorman 2005:52). This is true in many nations, such as the UK (Gorman 2005:52).

Interestingly, in France, Arabs and Africans who immigrated from their former French

colonies—those who were previously forced hosts to French colonists—to France do not receive

hospitality nor are they granted the same sort of permanency that French colonists did in their

countries: “A Right to visit was not a right to stay” (Gorman 2005:54). This is relevant for the

Diciotti off the coast of Catania. These migrants were coming from the former Italian colony of

Eritrea yet were denied access to the very colonial power that forced Eritreans in their homeland

to open their doors permanently. Nationalist and pro-migrant groups likely perceive this colonial

history differently.

Both nationalist and pro-migrant Sicilians belong to the same community, and identity

plays a primary role in the different ways arancini are represented. The offering of arancini is a

public, symbolic act of hospitality. Tom Selwyn’s and Derrida’s work on hospitality can been

applied to study identity and inclusion if arancini are indeed portrayed as symbols of inclusion,

as claimed in this paper. According to Selwyn, an act of hospitality, such as the offering of

arancini, represents social structures and “provide[s] the symbolic means to enable people to join

18

or leave social groups” (2001). This means that, as the Sicilians perform this act of hospitality at

the local level, they are symbolically inviting the migrants off the coast of Catania into their

Mediterraneanized community, protesting a centralized government that would otherwise restrict

inter-Mediterranean networks via migration (Ben-Yehoyada 2011). Thus, if the migrant were to

accept arancini, he or she would symbolically join this community.

For Derrida, hospitality is always limited and conditional (2000). The case of the Diciotti

exemplifies how quickly hospitality can change and how it is debated; potentially dividing popu-

lations around their ideological positions. Hospitality doesn’t simply mean welcome; and even

pro-immigrant Sicilians appeared uncomfortable with the arrival of the Diciotti and its passen-

gers. Furthermore, the government did show a degree of hospitality when it allowed some peo-

ple off the ship. Nevertheless, the few who did exit the Diciotti were minors and the motive was

less one of welcome and one presumably made to avoid legal challenges and a moral backlash by

the public. Picking minors skirted larger issues and minimized the threat posed to the national-

ists. Who should receive hospitality and what that hospitality might mean was left to be dealt

with later. Aranchini were offered but the status of the passengers as guest or a parasite, or what

might be a good or a bad migrant, was left for another day.

Arancini also function to support social networking. Building upon Selwyn’s arguments

in An Anthropology of Hospitality, the act of offering arancini by pro-migrant Sicilians is meant

to establish or maintain relationships (2001). Nationalists are not interested in building or keep-

ing such relationships. To Selwyn (and Derrida 2000), hospitality “turns strangers into familiars,

enemies into friends, friends into better friends, outsiders into insiders, non-kin into

kin” (2001:19). This act of hospitality establishes new relationships with the migrants departing

19

from North Africa. At a more symbolic level though, arancini maintain the long-standing rela-

tionship with the southern Mediterranean described throughout this paper. These relationships

are built or maintained by exchanging goods or services, both material and symbolic, between

the host and guest—the Sicilian local and the foreign migrant (Selwyn 2001; Smith 2012). Inter-

estingly, the offering of arancini to greet migrants is theoretically both a material and symbolic

exchange. I use the word “theoretically” as it is not clear if the protesters expected to be able to

hand migrants arancini (see above).

Arancini can be viewed through a materialist perspective as a food that fulfills nutritional

requirements, and which is convenient for travelers due to its shape and composition. Yet, it is

also a symbol of Sicily and its history, a symbol of mobility, liberty, and finally, a symbol of wel-

coming that, when given, reaffirms its original role as a symbol of Sicily because Sicilian culture

necessitates hospitality—particularly through food.

Just as commensality forms or maintains bonds as people eat together, Selywn argues that

hospitality—which he says is critical to forming or maintaining relationships—is the very way

by which societies “change, grow, renew, and reproduce themselves” (Selwyn 2001:18-37;

Crowther 2013:149). Crowther adds that food is the ultimate expression of hospitality, and a pub-

lic demonstration of identity and being (also see Turner 1974).

Selwyn argues that “the opposite of giving hospitality” is deciding to “ignore the other’s

existence” (2001:18-37). However, the problem with this, or at least how it is phrased, in the Si-

cilian example is that the nationalists who did not offer arancini and who opposed inclusion did

not just simply ignore the migrants’ existence. By supporting the government’s decision to pro-

hibit migrants from disembarking, the Sicilian nationalists actively acknowledged the Other’s

20

existence while rejecting any opportunity for membership in the community. Similarly, there is

an assumption that hospitality “is neither voluntary nor altruistic, but both necessary and com-

pulsory” (Selwyn 2001:19-37). In this framework then, the act of offering arancini to migrants

was not out of goodwill and choice, but out of necessity and as a way to recreate social engage-

ment; and while this connection should occur regardless of how a protestors felt towards migra-

tion and the migrant, the reality is complicated as nationalists actively reject migration, thus

showing that there is free will in hospitality since the two groups behaved in completely opposite

ways.

Some scholars believe that food and acts of commensality are the ultimate expression of

hospitality, reproducing society in the process (Selwyn 2001; Crowther 2013:149). Food may be

the most effective way in which people connect through culture and establish identity. Turning

this traditionally local act of hospitality (greeting traveling guests with arancini) into an act of

solidarity with those migrating from across the Sea symbolically extends the community to in-

clude the Mediterranean, uniting the Sea and its inhabitants via the sharing and celebration of

arancini. In this sense, arancini become a part of the system that defines local habitus in Sicily—

a strategically shared symbol that creates and recreates obligation, commitments and attitudes

through time and across cultural landscapes (Bourdieu 1995).

Beyond the local expression of identity, arancini are transnational. They extend the com-

munity beyond Catania, beyond Sicily, and reach the Southern shores of the Mediterranean and

nations of North and West Africa. While the nationalists largely react to increasing globalization

by emphasizing the local and rejecting the global, the two are not inherently opposed to one an-

other; one does not have to replace the other.

21

Mintz and Du Bois demonstrate that the global does not necessarily have to replace the

local (2002). Rather, the global can reinforce the local and potentially create a framework for a

hybrid order of the two to emerge (Mintz and Du Bois 2002). Through the sharing of arancini,

the local comes to signify the global; and for pro-immigrant Sicilians, sharing of arancini became

a public display of traditional concepts of hospitality. Yet the nationalists pushed arancini not as a

global symbol, rather emphasizing its local value. The exchange between the two groups created

a dialectical process wherein the symbol (arancini) is transformed and used in the construction of

identity. The importance of arancini in this process is clear given the almost obligatory traditional

hospitality that is critical to Sicily and Sicilian identity. Tierney and Ohnuki-Tierney as well as

Krishnendu Ray point out that we must pay attention to the local as well as the global to under-

stand how local traditions, meanings, and food create identity and belonging on the global stage

and through migration (Tierney and Ohnuki-Tierney 2012; Ray 2004). Food is a critical tool to

“understand individual cultures and societies, especially in the context of global and historical

flows and connections” (Tierney and Ohnuki-Tierney 2012:117; and see Wolf 1982; Comaroff

and Comaroff 1993). Therefore, it is through food that the global and local are in a dialogue; and

it is through arancini that the pro-migrant Sicilians engage in debate with the nationalists. The

pro-migrant protestors all brought arancini, not just any food; this is one example within a larger

food theory framework in anthropology where foods become powerful in the symbolic sense. For

Mintz, sugar becomes very symbolic because it was fundamental to (and representative of) trade,

slavery, and industrialization (Mintz 2002). Similarly, arancini are fundamental in the debate on

Sicilian identity and migrant reception.

22

On a smaller scale, locals engage in dialogue through arancini with the State as well

(Wolf 1982). The pro-migrant and nationalist groups are both focused on the State, not the mi-

grants, because it is ultimately the national government’s decision whether the migrants can dis-

embark or not. While certain foods can be considered iconic of a given place, this case study il-

lustrates that there is much greater complexity than simple representation of a place, as the food

is employed by groups with differing agendas in varying ways (Wolf 1982).

23

Arancini in the anthropological imagination:

This paper focuses on how two opposing parties use food to relay messages about identi-

ty and culture. Both groups of Sicilians may agree that arancini are the ideal food for traveling

and offering hospitality. While these two sides might agree that arancini are symbolic of Sicilian

culture and history, they contest the ways in which arancini are used—and who can receive them

—as well as the deeper meanings behind the food. To protestors in support of migrant arrivals,

arancini are the traditional Sicilian welcome to foreign travelers and a display of hospitality and

solidarity; they are symbolically extending their community to these migrants. As for the

counter-protesting nationalists in support of the State, they portray arancini as a symbol of Sicil-

ian/Italian culture and cuisine that stands alone. They have nationalized traditional foods and

made them strictly Sicilian. For this camp, arancini do not welcome, rather they limit and isolate

the migrant and criminalize migration.

The events of August 2018 are significant in that Sicilians gave a new meaning to a food

emblematic of Sicily and Sicilian identity, offering a fascinating insight into identity and transna-

tionalism in the context of contemporary globalized migration. Since the protestors could not ac-

tually hand migrants the arancini, the act became purely symbolic, but significant nonetheless. I

thus analyze how the pro-migrant protestors and the government-supporting nationalists contest

the meaning of arancini, and, ultimately, Sicilian culture itself.

There are many ways to address the offering of arancini as a symbolic exchange. It is a

symbolic exchange that informs us much about public displays, culture, identity, and transna-

tionalism. Food, though symbolic, is a very basic and important element of material culture and

nutrition.

24

What we cook and eat can be associated with one’s political stance. In this case, it is what

we cook and give that is highly associated with one’s political stance. In this situation, the very

essence of giving arancini or not giving arancini is inherently tied to where one stands on the

topics of immigration and asylum. Sicilians cook the material form of arancini that, over time,

came to represent the island’s culture and heritage.

People form group identity by consuming the same things in the same general fashion;

food indicates social groups and identity (Tierney and Ohnuki-Tierney 2012). Nationalists want

to keep arancini as a symbol that is exclusively Sicilian and limited to Sicilians. Arancini are

symbols of hospitality, but the way and to whom the host gives the arancini relates to how a giv-

en individual views his or herself, the potential receiver, as well as the group’s identity. For ex-

ample, the protestors see it as their obligation as Sicilians to help those in need. By gathering in a

public space and communally offering arancini and representing the act as a vital aspect of Sicil-

ian culture, the pro-migrant group is asserting its position over the nationalists.

We can apply Mary Douglass’ work on food and religious values of the pure and impure

and adapt it to fit the Sicilian example. The focus is not food itself, but on how people depict

themselves and distinguish themselves from others through food. This is helpful because it illus-

trates how two groups shape their identities through their opposition to each other; it shows how

ideas of what is positive and what is negative correlate with group ideologies and identities. In

Douglass’ words, a “polluting person is always in the wrong” and creates a danger for society,

while one’s own group is in the right (1966:12). Both groups in question use arancini to create a

sense of identity and belonging, and the two groups are in opposition.

Pro-migrant Sicilians use arancini to include outsiders and view the nationalists as

25

wrong. The nationalists reject outsiders and believe that the pro-migrant camp is in error. The

two groups read the past differently and use that history as they create their contemporary views

of Sicilian identity. Both sides create structures around what arancini is [see table 1].

Table 1: Pollution versus Purity Quadrants; Mary Douglass’ concept of purity versus pollution applied to migrant

reception

Nationalist Perspective

+ —

Immigrants/refugees

++

Nationalist groupX axis=Culture— —

Pro-migrant group

— +

Immigrants/refugees

Y Axis=Economy

Pro-migrant perspective

+ —

Immigrants/refugees

++

Pro-migrant groupX axis=Culture— —

Nationalists

— +

Immigrants/refugees

Y Axis=Economy

26

These quadrants illustrate how the two Sicilian groups model their positions vis-à-vis the other. It

also captures how migrants are caught between these two parties, despite being a focal part for

the contention of arancini’s symbolic meaning. Pro-Migrant Sicilians use the symbolism of the

arancini to make themselves special and distinct from the nationalists, and the nationalists do the

same. By placing themselves in a distinct category from each other, both groups are signaling to

each other, to migrants, to and the world at large their views on identity and their opposition to

the each other’s worldviews, fighting for the right to lay claim to Sicilian identity. Despite both

groups technically collectively sharing this symbolism and culture, both lay claim to the true

right to represent of Sicilian identity, with the pro-migrant group using food to do so.

Food is the collective property of the group just as symbols themselves are collective,

shared property (Geertz 1973). According to Geertz, symbols and meaning are public, and it is

systems of meanings that produce culture. Geertz argued that that symbols are the “medium thru

which man imposes a structure” and arancini are just such symbols for the Sicilians (1973).

Arancini are a unifying symbol for the pro-migrant group and stand in contrast to the na-

tionalists and the coalition government. Thus, this food and how it is used creates group identity

within the broader Sicilian and Italian communities. For Geertz, culture is not confined to peo-

ple’s brains; it is not private, nor are symbols. Culture is manifested or expressed by observable,

public symbols, which are the “vehicles of culture” (Ortner 1983:129). Because symbols repre-

sent a culture’s worldview and values, the goal of Geertz’ symbolic anthropology is to study the

way symbols “shape” views of the world (Ortner 1983:129). It is necessary to go

27

beyond the actual act being observed (offering of arancini to the migrant) to understand deeper

social systems and the views of the two Sicilian groups (Geertz 1973).

Turner’s more functional symbolic approach offers a useful way to model the use of

arancini in Sicily He emphasizes the ambiguous and dynamic nature of symbols; and we can ap-

ply this to the role of arancini in Catania, where two groups from the same community contest

the meaning and significance of a shared symbol (Turner 1975:145-159; Hoskins 2015:860-1).

Arancini as a symbol is important for both groups of Sicilians, as it is agreed upon to

symbolize Sicilian identity, but in different ways. Also, the ways this symbol is employed to rep-

resent Sicilian identity is contested. However, where Geertz is interested in symbols as “vehicles

of culture,” Turner is interested in how symbols are used to transform society and “trigger social

action” (Hoskins 2015:860). Turner states that rituals and cultural “performances,” such as the

hospitable, public act of offering arancini to the migrants, are not just expressions of the culture,

but are themselves agents of change (quoted in Hoskins 2015:861).

While Geertz saw symbols as part of a cultural system, Turner viewed them as vectors of

change in social, physical, economic, and political realms. In this case, the symbolic gesture of

offering arancini indeed triggered further social action. Less than two weeks following the

protests, there were more than 315,000 tweets about the Diciotti’s passengers being prohibited

from disembarking in Catania, according to the BBC (Rannard 2018). These tweets ranged from

those using the hashtag “Catania Welcomes” (#CataniaAccoglie)—referencing the aforemen-

tioned sign seen in protests that depicted arancini—and “National Disgrace,” to those in support

of Matteo Salvini’s [Northern] League (Rannard 2018). The latter tended to show support and

solidarity with Salvini, using phrases like “No Way [can/should we accept more

28

migrants]” (Rannard 2018). The acts of August 2018 thus triggered a social movement—

or perhaps two social movements—polarizing both sides of the debate. The subsequent events

that took place on social media as well as in the physical, political climate prove symbols’ trans-

formative abilities, but that does not mean that the existing symbolic importance of arancini—the

existing cultural system—did not allow for these protests and contention of arancini to happen.

Both groups attempted to reinforce Sicilian identity. Nationalists by keeping arancini for

themselves and rejecting its international origins as well as the migrants that were arriving. They

believe they were preserving Sicilian culture from outside forces that would destroy the island.

Pro-migrant Sicilians believe that offering arancini, and food in general, reinforced the Sicilian

obligation of hospitality, to help those in need and/or to travelers. It can be argued then that the

very essence of Sicilian culture is being contested.

Symbols are “manipulable” and multi-functional as well (Turner 1975:146). They are

malleable in that both sides present and use and adapt arancini to fit their own ideologies and

agendas. This is not new: symbols regularly have multiple functions and reference a diversity of

possibilities. Nevertheless, the function and meaning of public symbols (and in this case, aranci-

ni) are not homogenous and symbols themselves are not passive. Individuals and their communi-

ties share and contest interpretations, and they have agency to create and contest meaning (Bour-

dieu 1995).

29

Conclusion:

The events that took place in August 2018 in the port of Catania, Sicily sparked a contro-

versial debate in Sicily, Italy, and the greater Mediterranean. About a week after the protests, an

agreement was reached. The Catholic church offered to take most of the remaining migrants on-

board, with Ireland and Albania taking about twenty each (Chung 2018). This incident caused a

huge uproar in the world of politics and in the courts. Political debate ensued regarding migration

policies, and legal battles erupted when Sicilian politicians sued de facto leader of Italy Matteo

Salvini over his refusal to let those stranded at sea to embark; Salvini used the investigation to

bolster his nationalists’ support (Chung 2018). Further polarization occurred as a result. These

legal battles continue, and migrants have also tried to sue the government for this incident.

By wielding Sicily’s emblematic arancini to greet migrants, in opposition to counter-

protesting nationalists, pro-migrant Sicilians transformed a local symbol of hospitality and mo-

bility into a transnational one. By doing so, they symbolically extended membership of their

community to those beyond the borders of the EU. Whether or not they intended this protest

against migration policy to be purely symbolic, as protesters wielded signs that depicted the food

as a literal symbol of welcome, it became a purely symbolic act since no material exchange

could occur. The nationalists rejected the inclusion of more migrants, supporting closed borders

and rejecting arancini’s use as an expression of Sicilian solidarity and openness to outsiders. Na-

tionalists would use arancini as a symbol of Sicily and Sicilian heritage—which must be safe-

guarded and kept sacred and clean—and would argue that the power of arancini’s symbolism

should not be applied externally to invite outsiders in, but rather be used as a symbol of the

30

island’s unique heritage and community that should be used internally among Sicilians and for

Sicilians. By not offering arancini to migrants, they are thereby acknowledging them as

strangers/outsiders and are not welcome. These nationalists are rejecting migrants at a symbolic

level, whereas the government is doing it at the legal level, reflecting the same beliefs and val-

ues. The discrepancy between the two groups relates to the fact that the two groups read history

differently and view themselves, Sicilian identity in general, and the Other in opposing fashion.

31

Appendix A. Recipe for Arancini

Arancini al burro

Cook Time: 50 mins

INGREDIENTS

For the rice:

2½ cups risotto rice (short or medium grain, like Arborio or Carnaroli)

3 tablespoons butter

½ teaspoon saffron , diluted in 2 tablespoons of hot water

6 cups vegetable broth (or water)

Salt

Pepper

For the stuffing:

Bechamel sauce (see recipe below)

3 oz. ham , diced

3 oz. cheese (mozzarella, scamorza or provolone), diced or shredded

For the Bechamel sauce

2 cups milk

5 tablespoons butter

½ cup flour

A pinch of nutmeg

Salt

For the coating:

1 cup flour

1 cup water

32

1½ cup breadcrumbs

For frying

Vegetable oil

INSTRUCTIONS:

For Rice:

In a pot over medium heat, toast the rice with the butter for 2 minutes while stirring.

Start adding one ladle of broth and the saffron, and stir.

Continue cooking the rice over medium heat for at least 20 minutes, while stirring and adding

one ladle of broth at a time, until the rice is fully cooked.

Let rice cool to room temperature.

Season with salt and pepper and mix well.

Bechamel Sauce

In a saucepan, melt the butter over medium-high heat until foaming.

Stir in the flour to form a paste.

Lower the heat to medium, and cook, stirring constantly for 2 to 3 minutes.

Whisk in the milk until smooth, and add a pinch of nutmeg.

Bring to a simmer, and continue to cook, stirring, until the bechamel sauce is thick enough to

coat the back of a spoon, about 5 minutes.

Season with salt and pepper.

For Arancini:

Mix the bechamel sauce with the ham and cheese.

Put a generous spoonful of rice in one hand and flatten it against the palm in order to obtain a

hole in the center.

Fill the hole with a tablespoon of filling.

Cover everything with a little rice and form the shape of a small orange (or a cone if you prefer).

Then prepare a liquid batter by mixing the flour and water. Season with salt.

Dip the rice balls first into the batter and then into the breadcrumbs.

33

Heat a large volume of oil in a pot at medium-high heat.

Deep fry the rice balls, a few at a time.

Remove the rice balls when they are golden brown and place them on a plate lined with paper

towel.

Serve the rice balls warm or at room temperature

34

Bibliography

Albahari, Maurizio. (2009). Between Mediterranean Centrality and European Periphery: Migration and Heritage in Southern Italy. International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies 1(2): 141-162.

Albahari, Maurizio. (2006). Death and the Moral State: Making Borders and Sovereignty at the Southern Edges of Europe. Working Paper 136, The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California at San Diego.

Albertazzi, Daniele, Arianna Giovanni, and Antonella Seddone. (2018). ‘No Regionalism Please, We Are Leghisti !’ The Transformation of the Italian Lega Nord Under the Leadership of Matteo Salvini. Regional & Federal Studies 28.5: 645-671.

Benayoun, Mike. (No date). Italy: Arancini al Burro. 196Flavors.com.

Ben-Yehoyada, Naor (2011) 'The Moral Perils of Mediterraneanism: Second-Generation Immigrants Practicing Personhood between Sicily and Tunisia.’ Journal of Modern Italian Studies 16.3:386-403.

Ben-Yehoyada, Naor. (2015). ‘Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men’: The Moral and Political Scales of Migration in the Central Mediterranean. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 22.1:183-202.

Ben-Yehoyada, Naor et al. (2016). L’economia della Pesca di Mazara del Vallo in Prospettiva Storica. Strumenti Res. 8.1.

Ben-Yehoyada, Naor. (2017). The Mediterranean Incarnate: Region Formation between Sicily and Tunisia since World War II. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1995). Physical Space, Social Space and Habitus. Institutt for sosiologi og samfunnsgeografi. Universitetet i Oslo.

Bullaro, Grace Russo. From Terrone to Extracomunitario: New Manifestations of Racism in Contemporary Italian Cinema. Kibworth, UK: Troubadour Publishing.

Chung, Amy. (2018). “50 Migrants from the Diciotti Ship ‘Disappear’ in Italy.” Euronews.

Cohen, Jeffrey H. and Ibrahim Sirkeci (2011). Cultures of Migration: The Global Nature of Contemporary Migration. Austin: University of Texas Press.

35

Comaroff, Jean and John L. Comaroff. (2008). Occult Economies and the Violence of Abstraction: Notes from the South African Post-Colony. Journal of the American Ethnological Society 26.2:279-303.

Counihan, Carole. (2000). The Anthropology of Food and Meaning. New York: Routledge.

Crowther, Gillian (2013), Eating Culture: An Anthropological Guide to Food, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Derrida, Jacques. (2000). Of Hospitality. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Dickie, John. (1999). Darkest Italy: The Nation and Stereotypes of the Mezzogiorno (1860-1900). Houndmills: Macmilla.

D’Ignoti, Stefania. (2019). The Gendered Fight Behind Sicily’s Most Iconic Snack. BBC Travel.

Dore, Margherita. (2019). “Food and Translation in Montalbano.” In Food Across Cultures: 23-42. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Douglass, Mary. (1966). Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Abingdon: Routledge.

Garau, Eva. (2015). Politics of National Identity in Italy: Immigration and ‘Italnità.’ Abingdon: Routledge.

Giglioli, Ilaria. (2017) Producing Sicily as Europe. Migration, Colonialism and the Making of the Mediterranean Border between Sicily and Tunisia. Geopolitics. 22(2): 407-428.

Giglioli, Ilaria. (2017), From 'A Frontier Land' to 'A Piece of North Africa in Italy': The Changing Politics of 'Tunisianness' in Mazara del Vallo, Sicily. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 41: 749-766.

Geertz, Clifford. (1973). The Interpretation of Culture. New York: Basic Books.

Hoskins, Janet. (2015). Symbolism in Anthropology. In International Encyclopedia of the Social& Behavioral Sciences. Oxford: Elsevier.

Mainwaring, Ċetta. (2019) At Europe's Edge: Migration and Crisis in the Mediterranean. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

36

Mintz, Sidney and M. DuBois (2002). The Anthropology of Food and Eating. Annual Review of Anthropology 31:1, 99-119.

Paynter, Eleanor (2019). Italy’s Shutdown of Huge Migrant Center Feeds Racist Campaign to Close Borders. The Globe Post.

O’Gorman, Kevin D. (2006). “Jacques Derrida’s Philosophy of Hospitality.” The Hospitality Review:50-7.

Ortner, Sherry B. (1984). Theory in Anthropology Since the Sixties. Comparative Studies in Society and History. 26:126-166.

POLITICO Research. (2020). Poll of Polls: Italy—National Parliament Voting Intention. https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/italy/.

Rannard, Georgina (2018). Diciotti: Rice Ball Protest in Italian Boat Row. BBC News.

Ratti, Anna Maria. (1931). Italian Migration Movements, 1876 to 1926. In International Migrations, Volume II: Interpretations. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ray, Krishnendu. (2004). The Migrants Table: Meals and Memories in Bengali-American Households. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Richardson, John E. and Monica Colombo. (2013). Continuity and Change in Anti-Immigrant Discourse in Italy: An Analysis of the Visual Propaganda of the Lega Nord. Journal of Language and Politics 12.2: 180-202.

Riley, Gillian. (2007). The Oxford Companion to Italian Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ruggeri, Francesco. (2018). Sicilian Visitors Volume 2 - Culture. Lulu. 401-3.

Ruta, Giorgio. (2018). Diciotti, la Protesta degli Arancini per i Migranti Bloccati al Porto di Catania. La Repubblica.

Selwyn, Tom. (2001). “An Anthropology of Hospitality”. In Search of Hospitality. Oxford: Reed Elsevier.

Smith, Valene. (2012). Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Statista Research Department. (2020). Number of Immigrants who Arrived by Sea in Italy from 2014 to 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/623514/migrant-arrivals-to-italy.

37

Tambini, Damian. (2012). Nationalism in Italian Politics: The Stories of the Northern League, 1980-2000. Abingdon: Routledge.

Tierney, Kenji and Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney. (2012). “Anthropology of Food.” In The Oxford Handbook of Food History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Turner, Victor. (1974). Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Turner, Victor. (1975). Symbolic Studies. Annual Review of Anthropology 1975.4: 145-161.

Wolf, Eric. (1982). Europe and the People Without History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wright, Clifford. (2003). The Little Foods of the Mediterranean: 500 Fabulous Recipes for Antipasti, Tapas, Hors D'Oeuvre, Meze, and More. Boston: Harvard Common Press.

38

Related Documents