-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

1/18

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765

Review article: The aetiology, investigation andmanagement of diarrhoea in the HIV-positive

patient

ARTICLE in ALIMENTARY PHARMACOLOGY & THERAPEUTICS · SEPTEMBER 2011

Impact Factor: 5.73 · DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04781.x · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS

29

READS

343

3 AUTHORS:

Nicholas A Feasey

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

30 PUBLICATIONS 341 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Priya Healey

Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University …

6 PUBLICATIONS 52 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Melita A Gordon

University of Liverpool

50 PUBLICATIONS 1,798 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Melita A Gordon

Retrieved on: 01 October 2015

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Melita_Gordon?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_7http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nicholas_Feasey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_4http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Priya_Healey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_4http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_1http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Melita_Gordon?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_7http://www.researchgate.net/institution/University_of_Liverpool?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_6http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Melita_Gordon?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_5http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Melita_Gordon?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_4http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Priya_Healey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_7http://www.researchgate.net/institution/Royal_Liverpool_and_Broadgreen_University_Hospitals_NHS_Trust?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_6http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Priya_Healey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_5http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Priya_Healey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_4http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nicholas_Feasey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_7http://www.researchgate.net/institution/Liverpool_School_of_Tropical_Medicine?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_6http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nicholas_Feasey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_5http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nicholas_Feasey?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_4http://www.researchgate.net/?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_1http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_3http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51509765_Review_article_The_aetiology_investigation_and_management_of_diarrhoea_in_the_HIV-positive_patient?enrichId=rgreq-f96cd786-fe15-4902-a49b-be284d9131ef&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzUxNTA5NzY1O0FTOjEwMjAzNDc0OTUyNjAyN0AxNDAxMzM4Mzg4Nzg5&el=1_x_2

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

2/18

Review article: the aetiology, investigation and management of

diarrhoea in the HIV-positive patient

N. A. Feasey*,, P. Healey & M. A. Gordon*

*Department of Gastroenterology,

University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK.

Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust

Major Overseas Programme, Blantyre,

Malawi.Department of Radiology, Royal Liv-

erpool University Hospital, Liverpool,

UK.

Correspondence to:Dr M. A. Gordon, University of Liver-

pool Gastroenterology Unit, Henry

Wellcome Laboratories, Nuffield Build-

ing, Crown Street, Liverpool L69 3GE,

UK.

E-mail: [email protected]

Publication data

Submitted 2 February 2011

First decision 23 March 2011

Resubmitted 28 June 2011

Accepted 30 June 2011

EV Pub Online 20 July 2011

This commissioned review article was

subject to full peer-review .

SUMMARY

Background

Diarrhoea is a common presentation throughout the course of HIV disease.

Aim

To review the literature relating to aetiology, investigation and management of

diarrhoea in the HIV-infected adult.

Methods

The PubMed database was searched using major subject headings ‘AIDS’ or ‘HIV’

and ‘diarrhoea’ or ‘intestinal parasite’. The search was limited to adults and to

studies with >10 patients.

Results

Diarrhoea affects 40–80% of HIV-infected adults untreated with antiretroviral ther-

apy (ART). First-line investigation is by stool microbiology. Reported yield varies

with geography and methodology. Molecular and immunological methods and spe-

cial stains have improved diagnostic yield. Endoscopy is diagnostic in 30–70% of

cases of pathogen-negative diarrhoea and evidence supports flexible sigmoidoscopy

as a first line screening procedure (80–95% sensitive for CMV colitis), followed by

colonoscopy and terminal ileoscopy. Radiology is useful to assess severity, distribu-

tion, complications and to diagnose HIV-related malignancies. Side effects and

compliance with ART are important considerations in assessment. There is a good

evidence base for many specific therapies, but optimal treatment of cryptosporidio-

sis is unclear and only limited data support symptomatic treatments.

Conclusions

The immunological response to HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy remains

incompletely understood. Antiretroviral therapy regimens need to be optimised to

suppress HIV while minimising side effects. Effective agents for management of

cryptosporidiosis are lacking. There is an urgent need for enhanced regional diag-nostic facilities in countries with a high prevalence of HIV. The ongoing roll-out

of antiretroviral therapy in low-resource settings will continue to change the aetiol-

ogy and management of this problem, necessitating ongoing surveillance and

study.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603

ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 587doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04781.x

Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

3/18

INTRODUCTION

Both acute and chronic diarrhoea have been recognised

as major complications of human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV) infection and the acquired immunodefi-

ciency syndrome (AIDS) since the early days of the pan-

demic, being described as ‘slim disease’ in Africa as a

result of the combination of watery diarrhoea and weight

loss that was characteristic.1 Definitions of chronic diar-

rhoea vary, but an accepted one is the abnormal passage

of three or more loose or liquid stools per day for more

than 4 weeks and ⁄ or a daily stool weight greater than

200 g ⁄ day.2 While acute bacterial gastroenteritis causes

blood stream invasion and death more frequently in

HIV-infected than in immune-competent patients,

chronic diarrhoea is also a massive problem for HIV

patients untreated with antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Case series from industrialised countries in the preanti-

retroviral (ARV) era (therefore involving untreated

patients) show that 40–80% of HIV-infected patients will

experience diarrhoea.3–5

Human immunodeficiency virus has an impact on

intestinal infection at all stages (by plasma CD4 count),

with additional aggregation of disease in individuals who

have increased susceptibility to diarrhoeal infection irre-

spective of CD4 count.6 While HIV associated diarrhoea

is most frequently caused by an opportunistic infection,

there are many non-infectious causes which should also

be considered. As the list of aetiological agents has

grown both with increased experience of HIV and as

powerful antiretroviral therapy (ART) has developed, sotoo has the array of investigations and therapeutics avail-

able to manage diarrhoea in HIV infection.

THE IMPACT OF HIV ON THE GASTROINTESTINAL

TRACT

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) causes pro-

gressive immunosuppression as a consequence of its tro-

pism for CD4+ T-lymphocytes which progressively

decline because of apoptosis. Following acute infection,

there is a sharp initial fall in the plasma CD4 count,

which is followed by recovery and then a progressivedeterioration in the plasma CD4 count. Monitoring this

deterioration in plasma CD4 count is the major surro-

gate marker of immune status and is often the principal

tool in guiding the timing of initiation of ART. Plasma

CD4 T-lymphocyte count is, however, an imperfect mea-

sure of immune status for a number of reasons; one of

these is that the majority of CD4+ T-cells do not reside

in plasma, but in mucosal surfaces, particularly the gut,

where they form a major target for HIV in early infec-

tion prior to the development of a CD8+ T-cell response.

Furthermore, the immunosuppression seen in HIV is

extremely complex and consequent on the effects of HIV

viraemia on multiple branches of the immune system.

The mucosal surface of the gut is a unique interface

through which water and nutrients are absorbed during

digestion, where multiple commensal bacteria thrive and

which forms a structural and immunological barrier

against infection. It is not surprising that HIV infection

causes profound changes in the GI mucosa and its func-

tions, given the concentration of cells susceptible to HIV

infection found there, nor that the GI tract is conse-

quently a major reservoir for HIV and also a focus of

viral reproduction from the earliest days of infection.7–9

AETIOLOGY OF DIARRHOEA

The aetiology of diarrhoea in HIV-infected patients is

multi-factorial. Although opportunistic infections are an

obvious cause to consider, there are also many non-infectious causes of diarrhoea in HIV. There is a lack of

high quality prospective studies of the aetiology of diar-

rhoea in countries with the highest prevalence of HIV

and some of the early studies, although of high quality,

were constrained by both the limits of understanding of

the range of opportunistic infections and the diagnostic

technology available early in the HIV epidemic. Table 1

summarises studies of the aetiology of diarrhoea in HIV

and Figure 1 schematically represents potential causes of

diarrhoea in HIV by disease stage.

INFECTIONS

Different claims have been made about the relative

importance of bacteria, viruses and protozoan parasites

in the aetiology of infectious diarrhoea complicating HIV

in different studies. A number of factors have affected

the results of these studies, including the stage of HIV

infection, the range of diagnostic tests available at the

time of the study and the geographical location of the

study. It is important to note that opportunistic infec-

tions may still be found in patients who are taking anti-

retroviral therapy, partly because of poor adherence.10

Bacterial infection

Human immunodeficiency virus infected patients are at

risk of acute diarrhoea from the same bacterial agents of

enterocolitis as those who are HIV negative. They

are, however, at greater risk of prolonged infection

and of invasive disease, particularly from nontyphoid

Salmonellae11 and from Campylobacter jejuni.12, 13

Recurrent invasive nontyphoid Salmonella (NTS) disease

N. A. Feasey et al.

588 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

4/18

T a b l e

1 | S u m m a r y o f s t u d i e s o

f a e t i o l o g y o f d i a r r h o e a i n H I V - i n f e c t

e d a d u l t s

S t u d y

S u b j e c t

L o c a t i o n

C o h o r t s i z e

T e c h n i q u e

M a j o r fi n d i n g s

S a k s i r i s a m p a n t e t a l . 1 3 1

I n t e s t i n a l p a r a s i t e s

T h a i l a n d

9 0 s t o o l s a m p l e s

M

i c r o s c o p y & P C R

4 6 % p o s i t i v e f o r

p a r a s i t e s , o f w h i c h : 3 0 %

C r . h o m

i n i s , 4 %

C r .

m e l e a g

r i d i s , 6 %

E .

b i e n e u s i 2 %

B . h o m i n i s ,

1 %

C .

c a y e t e n s i s , 1 %

I .

b e l l i

G o n c a l v e s e t a l . 1 3 2

C a u s e s o f d i a r r h o e a

c a s e c o n t r o l s t u d y

B r a z i l

4 0 p a t i e n t s w i t h

d i a r r h o e a , 6 0

w i t h o u t

M

i c r o s c o p y , c u l t u r e

E I A & P C R

C a l i c i v i r u s , C . p a r v u m

& G .

l a m b l i a s i g n i fi c a n t l y

a s s o c i a t e d w i t h d i a r r h o e a

D i l l i n g h a m

e t a l . 1 3 3

M o r t a l i t y : H I V

a s s o c i a t e d

d i a r r h o e a

H a i t i

2 8 8 p a t i e n t s

S t o o l m i c r o s c o p y

3 3 % h a

d a n e n t e r i c p a t h o g e n

i d e n t i fi e d : C r y p t o s p o r i d i u m

s p p . ,

G i a r d i a

s p p . , I . b e l l i , C . c a y e t a n e n -

s i s , a n d

E . h i s t o l y t i c a .

C h a c i n - B o n i l l a e t a l . 1 3 4

M i c r o s p o r i d i o s i s

V e n e z u e l a

1 0 3 p a t i e n t s

S t o o l m i c r o s c o p y

M i c r o s

p o r i d i a l i n f e c t i o n s

w e r e d e t e c t e d i n 1 4 %

a n d 3 8 %

h a d o t h e r

p a r a s i t i c p a t h o g e n s .

C h a c i n - B o n i l l a e t a l . 1 3 5

C y c l o s p o r a

c a y e t a n e n s i s

V e n e z u e l a

7 1 p a t i e n t s

S t o o l m i c r o s c o p y

C y c l o s p

o r a o o c y s t s w e r e

f o u n d

i n 1 0 %

B l a n s h a r d e t a l . 1 3 6

C h r o n i c d i a r r h o e a

U K

1 5 5 p a t i e n t s

E x a m i n a t i o n o f s t o o l s ,

d u o d e n a l , j e j u n a l

a n d r e c t a l b i o p s y

s p e c i m e n s a n d

d u o d e n a l a s p i r a t e

f o r b a c t e r i a l ,

p r o t o z o a l a n d v i r a l

p a t h o g e n s

8 3 % h a d 1 p a t h o g e n : s t o o l

a n a l y s

i s i d e n t i fi e d t h e

m o s t p a t h o g e n s ( 4 7 % ) .

R e c t a l b i o p s y n e c e s s a r y

f o r t h e d i a g n o s i s o f C M V

a n d a d e n o v i r u s . D u o d e n a l

b i o p s y

w a s a s h e l p f u l a s

j e j u n a l b i o p s y a n d

d e t e c t

e d s o m e t r e a t a b l e

p a t h o g e n s m i s s e d b y o t h e r

m e t h o

d s . E l e c t r o n

m i c r o s c o p y , i m p r e s s i o n

s m e a r

s a n d d u o d e n a l

a s p i r a t e y i e l d e d l i t t l e e x t r a

i n f o r m

a t i o n .

B l a n s h a r d a n d G a z z a r d

1 3 7

P a t h o g e n n e g a t i v e

d i a r r h o e a

U K

3 9 p a t i e n t s

F o l l o w - u p o f a b o v e

c o h o r t

2 s m a l l b o w e l n e o p l a s m , 3

C M V

Review: diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603 589ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

5/18

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

6/18

has been considered an AIDS defining illness since

1985,14, 15 and advanced HIV-disease is associated with a

198–304-fold increased risk of invasive and multisite Sal-

monella infections.16 Diarrhoea may be a less prominentfeature of Salmonella infection in the setting of HIV.11

Campylobacter jejuni is another organism commonly

associated with diarrhoea in immunocompetent individu-

als which is an important cause of invasive disease and

morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected individuals. The

average incidence of Campylobacter among patients with

AIDS has been found to be 39 times higher than in non-

infected people,13 furthermore HIV-infected individuals

are much more likely to have debilitating disease requir-

ing prolonged courses of antimicrobials and in one series

the mortality of invasive disease was 33%.12

Otherspecies of this genus have also been implicated in diar-

rhoea in HIV. Other bacterial pathogens recognised to

cause diarrhoea more frequently in HIV-infected patients

include Escherichia coli, Shigella sp and Clostridium diffi-

cile. One study of trends in the aetiology of diarrhoea

proposed that C. difficile is the most common cause of

diarrhoea in HIV-infected adults in the US.17

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), caused by sero-

vars L1–L3 of Chlamydia trachomatis, is endemic in

Africa and the Carribean, and was rare in industrialised

countries prior to 2003. It is currently re-emerging as a

sexually transmitted infection among men who have sex

with men (MSM), and HIV is a risk factor for suscepti-bility. WhilE genital LGV causes painful groin lymphade-

nopathy, gut mucosal infection can cause an ulcerative

rectocolitis, and adenopathy of the deep nodes which

drain the rectum may go unnoticed until they coalesce

to form a bubo, which may rupture and fistulate. The

clinical picture and histology may both mimic Crohn’s

disease and clinicians must be alert to the potential for

misdiagnosis and mistreatment in this setting. It is likely

that depletion of mucosal CD4 cells plays a critical role

is susceptibility to LGV in HIV.18, 19

Mycobacterial infection

The likelihood of developing extra-pulmonary and dis-

seminated infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis

and nontuberculous mycobacteria increases as HIV-asso-

ciated immunosuppression progresses. Gastrointestinal

infection with numerous species of Mycobacteria may

occur in HIV. Both Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non-

tuberculous mycobacterial infection may present with

diarrhoea.20, 21 While diarrhoea is a relatively uncom-

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1 000

10 000

100 000

1 000 000

Time since infection

10 years0–6 weeks

V i r a l l o a d ( c o p i e s / m L )

C D 4

c o un t

HIVsero-

conversion

Bacterial infectionTuberculosis

Isospora belli

Cyclospora cayatanensisStrongyloides

GI malignancies

ART side effects

CD4 count after commencing ARTCauses of diarrhoea related to ART

CD4 count without ART

Cryptosporidiamicrospor id ia MAC, CMV

Diarrhoea related to HIV se roconversion

Causes of diarrhoea as HIV disease progresses

Viral load without ART

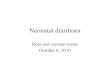

Figure 1 | Scheme showing causes of diarrhoea at different stages of HIV disease: following HIV seroconversion, CD4

count recovers to a set point, then falls gradually over 5–0 years. The coloured boxes schematically indicate causes of

diarrhoea at different stages of HIV infection based on CD4+ T-lymphocyte count (blue line). The black dotted line

indicates the impact of starting ART on CD4 count and the overlap between different categories after starting ART

highlights the potential diagnostic difficulty at that time.

Review: diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603 591ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

7/18

mon symptom of tuberculosis, it is more commonly a

feature of disseminated infection with members of the

Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). Disseminated

MAC infection occurs in advanced HIV and is frequently

associated with diarrhoea, which was reported to be

symptom in 17% of cases in one series.22

Parasitic infection

Numerous parasitic infections are known to cause diar-

rhoea in association with HIV. These include parasites

previously described to have pathogenic potential in HIV

negative patients (Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica,

Blastocystis hominis, Strongyloides stercoralis and other

soil transmitted helminths) and a number of parasites

either newly discovered or not previously thought to

have significant pathogenic potential, including Isospora

belli, Cryptosporidium parvum, Cyclospora cayetanensis,

and microsporidia particularly Enterocytozoon bienneusi

and Encephalocytozoon intestinalis. These organisms havesubsequently been identified as pathogens in otherwise

healthy people. The first three are intestinal spore form-

ing protozoa which cause intracellular infection and

which can lead to severe intestinal injury and prolonged

diarrhoea in advanced HIV,23 while microsporidia have

recently been reclassified as fungi. While some studies

have linked parasitic infection with progressive immuno-

suppression,24 others have questioned this association

and suggested that diarrhoeal infections aggregate in

HIV-infected individuals irrespective of CD4 count.6

Certainly risk factors for exposure to parasitic infection,particularly socio-economic status and access to safe

water and adequate sanitary facilities need to be consid-

ered when assessing an HIV-infected patient with

diarrhoea.

Viral infection

A number of viruses have been implicated in the aetiol-

ogy of diarrhoea in HIV-infected patients and the list

has grown and changed as advances have been made in

diagnostic virology. One of the first viral OIs to be listed

as an AIDS defining illness was Cytomegalovirus(CMV).25 CMV affects multiple organs in end stage HIV

and in the GIT can cause colitis. The hallmark is diar-

rhoea which may be bloody and accompanied by weight

loss, fever and abdominal pain. In early and pre-ART

cases series, CMV was a cause of approximately 15% of

HIV associated diarrhoea.26 The risk of CMV disease in

HIV is at its greatest as the CD4 count falls below

50 · 109 ⁄ L, consequently CMV related disease has rap-

idly declined with the roll out of ART.27 As with proto-

zoal OIs, the list of viral infections associated with

diarrhoea has grown substantially and now includes

astrovirus, picobirnavirus, caliciviruses (both norovius

and sapovirus) and adenoviruses.28 While these viruses

have been found significantly more frequently in the fae-

ces of patients with both HIV and diarrhoea than in that

of patients with HIV alone, causality has yet to be pro-

ven for all of them, particularly picobirnavirus.28 Diar-

rhoea is also a well documented feature of HIV

seroconversion illness itself.29, 30 This is important to

recognise as a combined antibody ⁄ antigen HIV test may

be negative during a seroconversion illness and if this

diagnosis is suspected, the HIV test should be repeated

12 weeks after the initial test.

Fungi

Candida species are frequently isolated from the stool of

HIV-infected patients31 and have been implicated in

antibiotic associated diarrhoea;32 however, their role inthe aetiology of diarrhoea remains unclear and further

studies are needed into the role of yeasts in HIV-associ-

ated diarrhoea. Systemic dimorphic fungal infection can

affect the gastrointestinal tract causing diarrhoea, for

example disseminated infection with Histoplasmosis.33

PATHOGEN-NEGATIVE DIARRHOEA

The concept of ‘pathogen-negative diarrhoea’ has evolved

as the understanding of the breadth of OIs which cause

diarrhoea has evolved. One study of patients classified as

having pathogen-negative diarrhoea on entry to thestudy observed that in the majority of the more severe

cases, an infectious cause was ultimately identified,34 fur-

thermore this study preceded the first reports of intesti-

nal microsporidiosis as a cause of diarrhoea in HIV.35

The hunt for novel infectious causes of enteropathy in

HIV-infected patients continues.

The role of HIV itself

Despite this, it is clear that there are changes in the bowel

attributable to HIV disease itself, which have important

functional significance. Massive and progressive depletionof gastrointestinal effector memory CD4+ T lymphocytes

is seen early in the course of HIV disease, and the simian

model disease SIV.36 The suggested mechanisms are direct

infection of cells and bystander cell death. One of the most

important consequences of this loss of gut mucosal CD4

cells is a failure to maintain the epithelial barrier function

of the gut mucosa.37 This mucosal damage enables micro-

bial products to translocate across the bowel. LPS levels in

both HIV and SIV have been found to be elevated and are

N. A. Feasey et al.

592 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

8/18

temporarily reduced following neomycin treatment.38

Translocated microbial products such as LPS, peptidogly-

can and viral genomes may cause chronic gastrointestinal

and systemic immune activation through stimulation of

the innate immune system via Toll-like receptors. The

resultant activated T-cells in turn are a further target for

HIV, thus driving a vicious circle in the immunopathogen-

esis of HIV disease.39, 40 The impact of HIV infection of

the gut mucosa may therefore extend to influence overall

progression of the disease systemically. These changes,

however, also have significant functional consequences for

the gut itself and also may be linked to the longstanding

observations that there is a jejunal enteropathy termed

‘HIV enteropathy’, associated with mild villous atrophy

and crypt hyperplasia.41–43 Increased permeability and

decreased absorption for sugars, vitamin B12 and bile have

been described, even in the absence of detectable opportu-

nistic infections, associated with chronic diarrhoea and

malnutrition in HIV.44–48 A third subset of T-lymphocyteshas recently been discovered and characterised, which act

through IL-17 to coordinate gut mucosal protection

against infection. The loss of the TH17 subset of CD4 cells

from the gut mucosa is thought to be particularly impor-

tant during HIV49 and in addition to the consequences for

HIV disease progression described above, the loss of IL-

17-producing T cells has been shown to permit invasion

and dissemination of nontyphoidal Salmonella from the

gut in an SIV model.50

Another suggested mechanism for HIV-related diar-

rhoea has been rapid intestinal transit due to damage tothe autonomic nervous system; HIV is known to be neu-

rotropic and a generalised autonomic neuropathy in

advanced HIV is well described.51 Increased transit time,

however, does not correlate well with symptomatic diar-

rhoea.45 HIV-associated inflammatory bowel disease,

which has been defined as ‘a non-infectious colitis refrac-

tory to standard treatment for inflammatory bowel dis-

ease’ is characterised by colitis52 or caecitis (typhlitis)53

and may also cause pathogen-negative diarrhoea.

HIV-associated malignancyHuman immunodeficiency virus-associated gastrointesti-

nal malignancies may also present with pathogen-negative

diarrhoea.4 Non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma and Kaposi

sarcoma are both AIDS-defining and are considered non-

infectious, although their pathogenesis is ultimately related

to oncogenic herpes viruses such as EBV and HHV8.

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are 60–200-fold

increased among HIV-infected patients, commonly EBV-

related, and the categories most likely to affect the GI tract

are Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphomas54, 55 and diffuse

large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL), which frequently pres-

ent with extra-nodal involvement including of the GI tract,

reflected by a predominance of gastrointestinal symptoms

including diarrhoea.56 Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL)

is known to be HIV-related and an extracavitary, solid var-

iant has recently been described which commonly affects

the gastrointestinal tract and is HHV8-associated, with fre-

quent EBV co-infection.57

Hodgkin lymphoma is also 10-fold over-represented in

HIV, although it is not AIDS-defining and its incidence

in HIV has a nonlinear relationship with CD4 count and

disease stage.58 Cases present with advanced disease, ex-

tranodal disease and ‘B’ symptoms, but not typically with

diarrhoea or luminal GI disease.57 The importance of the

GI-related non-AIDS defining malignancies Hodgkin

Lymphoma and anal carcinoma is increasing with the

advent of HAART as patients are living longer.

Kaposi sarcoma, caused by HHV8, is AIDS-defining and is a multifocal disease which very frequently involves

the GI sub-mucosa. While GI involvement is often

asymptomatic, Kaposi’s may present with diarrhoea,59, 60

GI bleeding (since it is a very vascular tumour), perfora-

tion, intussusception or obstruction.

Pancreatic disease

Human immunodeficiency virus infection may have mul-

tiple effects impairing exocrine pancreatic action, which

in turn may contribute to chronic diarrhoea through

impaired fat absorption. Factors associated with pancre-atic disease include OIs, viral hepatits, HIV itself and

ART,61 although the principal culprit, didanosine, is

rarely used now. One study found measurement of faecal

elastase to assess pancreatic exocrine insufficiency to

enable treatment with oral pancreatic enzyme therapy to

be useful in the management of chronic diarrhoea.62

Antiretroviral therapy as a cause of diarrhoea

In 1987, Zidovudine (AZT) became the first pharmaco-

logical agent with proven efficacy against HIV.63 In the

late 1990s, combination ART became the standard of care to combat the rapid emergence of drug-resistance

and it has been so successful that patients diagnosed

early in the course of HIV infection can expect a near

normal lifespan.64 Multiple classes of ARVs are now

available; however, these agents are not without side

effect and diarrhoea is a common consequence of ART

which may be severe enough to lead to discontinuation

of ARVs.65 While diarrhoea has been associated with all

three main classes of ARVs; nucleoside reverse transcrip-

Review: diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603 593ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

9/18

tase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcrip-

tase inhibitors (NNRTIs) and protease inhibitors (PIs),

perhaps the most problematic agents are the PIs, particu-

larly ritonavir,66 which is used to boost levels of other

PIs.67 The dosage of ritonavir and dosing schedules of

PIs is a subject of major interest.68

INVESTIGATION

An algorithmic approach to investigation and manage-

ment of chronic diarrhoea in HIV is shown in Figure 2.

To guide management, an accurate history concerning

the patient’s HIV, their treatment history and their pro-

fessional and recreational exposure to pathogens and their

travel history should be sought. All of the pathogens listed

are transmitted by the faecal-oral route and are all poten-

tially sexually transmitted. This information is equally

important for clinicians and medical scientists consider-

ing which tests to perform. Additional features of the his-

tory and examination may help distinguish between small

or large-bowel diarrhoea, and the possibility of complica-

tions. Although molecular diagnostics are predicted to

enhance the sensitivity of investigations in the future, the

majority of first-line clinical diagnostic tests routinely

available are still based on microscopy and culture.

Microbiological investigation

Upon making a diagnosis of HIV, the most basic investi-

gations necessary are a plasma CD4 count and HIV viral

load (see Figure 2). The CD4 count will help to assess

the degree of immunosuppression and thus clarify the

spectrum of OIs to which the patient susceptible. The

viral load is the most useful parameter of response to

ARVs and in early treatment failure will increase before

the CD4 count starts to decline.

Initial clinical assessment including:

Severity

Drug history

CD4 count and HIV Viral Load

Stool examination:

3 samples over 10 different days

Microscopy for ova, cysts & parasites

(ZN stain, trichrome stain)

Bacterial culture

C. difficile screen

Specific virology and protozoal PCR

Supportive management

Antimotility agents, adsorbents, cholestyramine,

octreotide, etc

Start or optimise ARVs to:control VL, minimise drug side effect

Review all other drugs, withdraw suspect drugs

Flexible sigmoidoscopy:

Biopsies for histology, standard and mycobacterial

culture and CMV PCR

Pathogen negative diarrhoea?

Colonoscopy with terminal ileoscopy

(or consider gastroscopy)Cross sectional imaging (malignancy, disease extent,

complications, tissue biopsy)

consider : double contrast upper GI barium study

consider : complete TB diagnostic work-up

Specific treatment for:

Additional infectious agents identified

HIV-associated malignancies

Mycobacterial disease

Empirical or specific treatment for:

Infectious agents

Figure 2 | Algorithm showing the management approach to the HIV patient with diarrhoea.

N. A. Feasey et al.

594 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

10/18

Investigation of faeces

Microbiological investigation of faeces should be the first

investigation of diarrhoea. Different specimens provide

different challenges to a diagnostic microbiology labora-

tory; faecal culture is made challenging by the difficulty

of ensuring that the pathogen or pathogens among a

diverse array of bacteria is identified. A faecal sample

should be collected and submitted soon as possible after

the onset of symptoms. While a 1–2 g specimen is suffi-

cient for routine culture, more is required for the array

of tests which may be necessary in the context of HIV

and diarrhoea. Specimens of faeces should be transported

to the laboratory and processed as soon as possible,

because a number of important pathogens such as Shi-

gella species may not survive the pH changes that occur

in faeces specimens which are not promptly delivered to

the laboratory, even if refrigerated.69 Three samples over

no more than a 10 day period are recommended for

detection of parasites, although more may be necessary,especially if Giardia is suspected. No more than one

specimen per day should be submitted as shedding of

ova and cysts tends to be intermittent.70

Once received by a diagnostic laboratory, specimen

processing depends on the clinical context, but should

include culture on a media which favours selection of

Salmonella sp and Shigella sp and a second which selects

for Campylobacter sp. Consideration should be given to

testing for Clostridium difficile toxins A and B. Recovery

of mycobacteria from stool is uncommon therefore

mycobacterial stool culture is not recommended.69

Stool should be examined using direct microscopy for

the ova and cysts of protozoal parasites; however, a screen

for Cryptosporidia, Cyclospora, Isospora and microsporidia

requires a specific request as these organisms require spe-

cific stains. A modified acid fast stain is used to look for

the oocysts of cryptosporidia, isospora and cyclospora,

although the sensitivity is unknown and operator depen-

dant. Examining multiple specimens increases sensitiv-

ity.23 Diagnosis of microsporidia is also challenging, in

part because their size (1–2 lm) makes them difficult to

differentiate from faecal debris by light microscopy.71

Improved methods include microscopy following staining

with modified trichrome stain72 with or without a chemo-

fluorescence brightener such as calcoflour white; however,

the gold standard test remains transmission electron

microscopy (TEM) on small bowel biopsy specimens.

Other methods include antigen and antibody based detec-

tion methods and nucleic acid amplification techniques.71

Nucleic acid amplification tests are increasingly used

in the diagnosis of sexually acquired infection. Since

2005 several such tests have become available for the

diagnosis of LGV from anal swabs. The clinician must

consider the diagnosis of LGV to make the diagnosis.

Virology

Diagnosis of the viral infections which cause diarrhoea is

complex and species specific. While TEM (performed on

tissue) and viral culture enable the identification of new

viruses and viruses not expected in a given clinical con-

text (i.e. non-enteric adenoviruses causing diarrhoea in

HIV positive patients), the skills required for these tech-

niques are rarely used outside of reference laboratories.

Increasingly, viral infections are diagnosed using

enzyme-immunoassay (EIA), latex agglutination kits or

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed on stool,

blood or tissue. In the context of CMV, assays for CMV

DNA or antigen in blood are superior to culture for doc-

umenting viraemia73 and few UK laboratories use CMV

culture. Further prospective studies are required to deter-mine whether PCR of blood or tissue is the most sensi-

tive assay for diagnosing intestinal CMV,74 however

histology gives the best indication of disease severity.

The rapid reduction in the cost of whole genome

sequencing may make mass sequencing a viable diagnos-

tic option in the near future. This approach will also

enable the discovery of novel viruses.

Other microbiology

In addition to stool samples, blood should be taken for

culture from febrile or septic patients and considerationshould be given to mycobacterial blood culture. If TB is

suspected, alternative microbiological specimens should

be sought including mucosal biopsy, lymph node tissue

or ascites for histology and culture, combined with

radiological evidence of TB, including a chest X-Ray in

all patients (http://www.nice.org.uk/CG033NICEguide-

line). The role of rapid PCR-based diagnostic tests for

TB is likely to expand. Blood for specific serology, anti-

gen testing or PCR may be useful; however, patients with

advanced HIV may lose the ability to mount an antibody

response to the point where serology is negative.

Endoscopy

There has been much debate about the usefulness or

necessity for pan-endoscopy to investigate stool-

negative diarrhoea in HIV. Not all studies are directly

comparable, since sensitivity clearly depends not only

on the extent of examination, but on the associated

microbiological methods used for both stool and

biopsy material, which have improved over time. Geo-

Review: diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603 595ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

11/18

graphical location, disease stage, the underlying risk

factor for HIV and the advent of HAART may also

be confounders in these studies. Endoscopy yields an

additional diagnosis in 30–70% of stool-negative cases,

depending on methods and the completeness of study.

Unsurprisingly, diagnostic yield is highest when there

are worse symptoms, and at lower CD4 count. The

commonest additional or new diagnoses uncovered by

endoscopy are CMV colitis, microsporidiosis and giar-

dia infection. There is a general consensus that 85–

90% of cases of CMV colitis will be detected using

flexible sigmoidoscopy and biopsy alone4, 34, 75–77 and

flexible sigmoidoscopy is generally considered a neces-

sary and adequate first-line assessment in stool-negative

diarrhoea. There are, however, a smaller number of

studies suggesting that proximally distributed CMV

colitis or other colonic diagnoses may be missed and

full colonoscopy (preferably with terminal ileoscopy) is

warranted if severe or functionally debilitating symp-toms persist.26, 78 Although some studies have sug-

gested that biopsy of the small bowel, either at

duodenoscopy or terminal ileoscopy, is necessary to

reliably diagnose microsporidiosis,76 improved microbi-

ological stool methods such as PCR or trichrome stain

mean that the necessity for small bowel biopsy is now

reduced. The high pick-up rate for microsporidiosis in

the terminal ileum, combined with the detection of

proximally distributed CMV colitis, means that colo-

noscopy with terminal ileoscopy is a logical second-line

investigation and may obviate the need for upper GIendoscopy. The decreasing utility of upper GI endos-

copy to diagnose pathogens in HIV is confirmed in

other recent studies.79

Radiology

Radiology of opportunistic infections and inflammatory

disease. Interpretation of diagnostic imaging of the

HIV-infected patient presenting with diarrhoea can be

challenging as the appearances are usually nonspecific.80

The most common findings in infectious diarrhoea are

of oedematous and ulcerated mucosa. The distributionand type of ulcers and the extent of disease when corre-

lated with the degree of immunosupression can aid in

narrowing the wide differential diagnosis of the various

infectious pathogens, but endoscopic samples need to be

obtained for histopathological or microbiological investi-

gation to make a definitive diagnosis.81, 82

Literature on the appearances of the bowel in patients

with diarrhoea and HIV is sparse. Imaging of mucosal

detail, such as the pattern and distribution of ulcers and

oedema, is best seen in barium studies. Mucosal detail is

not apparent on CT or MRI and the appearances of the

bowel are not pathogen specific. CT or MRI scanning is

undertaken in patients with more severe disease to assess

disease distribution, potential complications, for staging

tumours and to aid intervention. If these modalities are

unavailable, ultrasound may demonstrate small and large

bowel thickening.83

While a tissue or microbiological diagnosis must be

sought, imaging can suggest certain diagnoses. Tubercu-

losis commonly affects the ileocaecal region resulting in

mural thickening of the terminal ileum and caecum. Skip

areas in the small bowel may mimic Crohn’s disease with

luminal narrowing and proximal dilatation, but the pres-

ence of skip lesions with ileocaecal involvement is

strongly suggestive of TB. Necrotic mesenteric lymphade-

nopathy can be seen on CT and is also suggestive of TB

infection.84 Advanced disease results in the classic

appearance of a conical small caecum. Colonic involve-ment results in segmental ulcers, strictures and polypoid

hypertrophic lesions.

Mycobacterium avium affects the jejunum with thick-

ening of the folds, but there is no ulcer as MAI is not

associated with tissue destruction. Normal appearances

are seen in 25% of infected patients undergoing CT.85

Cytomegalovirus infection most commonly affects the

colon and radiological appearances vary depending on

the severity. Bowel wall thickening, ulcers and irregular

folds are seen on barium studies and CT. With increas-

ing severity of disease, large ulcers, nodular defects andpseudo-membranes may develop. Tumour like lesions

may develop which may be indistinguishable from neo-

plasia.86 Thrombosis secondary to vasculitis with subse-

quent ischaemia may result in penetrating ulcers and

subsequent perforation.87 Histoplasmosis also affects the

colon, particularly the ascending colon. The thickening

of the bowel and pericolonic inflammatory change can

mimic carcinoma.88

Human immunodeficiency virus-related typhlitis (cae-

citis) is localised inflammation of the caecum with sym-

metric wall thickening, pneumatosis and pericolonicinflammation. This can extend to involve the terminal

ileum and ascending colon.89 Diagnosis takes account of

and is based on the entire clinical picture, rather than by

imaging alone. CT imaging is particularly useful to

exclude a perforation or abscess and to guide

intervention.90

Radiology of neoplastic lesions. The lesions of Kaposi

sarcoma are submucosal in location and can affect any

N. A. Feasey et al.

596 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

12/18

part of the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly the

duodenum. Barium studies in the early stages may be

negative as the lesions are submucosal and diagnosis

may be more readily achieved endoscopically. When

advanced, both barium studies and CT may demonstrate

larger flat or polypoid submucosal masses with or with-

out ulcers and associated fold thickening. Enhancing

lymph nodes are seen commonly in patients with dis-

seminated disease which may aid diagnosis. Otherwise,

the lesions may mimic other neoplastic lesions such as

carcinoma, metastases or lymphoma or infections.91

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-

Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) in HIV has been found to

affect extra-nodal sites in 86% of abdominal CT scans,

the commonest being the GI tract.92 Primary B-cell lym-

phoma in HIV patients often affects the distal small

bowel. Thickening of the distal ileum, mass like lesions,

ulcers and aneurysmal dilatation may be seen on CT with

extension of tumour into the adjacent mesentery andlymph nodes. Barium studies are nonspecific demonstrat-

ing polypoid mass lesions, ulcers and infiltrative change

or nodularity. Intussusception and bowel obstruction may

occur and the appearances may be indistinguishable from

carcinoma.93 The patterns and distribution of intestinal

findings on CT imaging of small bowel NHL are not dis-

tinguishable from those seen in HIV-uninfected cases.94

Other investigations

A diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) com-

plex can be inferred from a localised immune reaction tointradermal injection of Mycobacterial purified protein

derivative (PPD, the tuberculin test). More sophisticated

ex-vivo tests based on detection of interferon gamma

release in response to two antigens specific to MTB (and

which are not found in the BCG vaccine) have recently

been introduced. Interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs)

may be more sensitive than intradermal PPD in HIV-

infected adults.95 More work needs to be carried out to

define the role of IGRAs in the diagnosis of extrapulmo-

nary TB in HIV-infected adults and no studies have

focused on the use of IGRAs in intestinal tuberculosis.Despite this, a positive tuberculin-test or IGRA may be of

value in supporting a diagnosis of MTB,96 while a negative

result should be interpreted with caution.

MANAGEMENT AND OUTCOMES

Treatment of infectious diarrhoea by aetiology

The first steps in managing diarrhoea in the context of

HIV are the same as those taken in managing any acute

diarrhoea; to evaluate which pathogens the patient is at

risk of by taking a careful history and to assess and man-

age dehydration, although known HIV infection should

lower the threshold for using antimicrobial therapy.

There is increasing, but geographically heterogeneous

resistance to multiple antimicrobials among enteric

pathogens, making recommendation of an empirical

antimicrobial unrealistic, instead expert local advice

should be sought or local guidelines consulted in the

management of the critically ill patient. Ultimately, iden-

tification of specific organisms by culture will enable

antimicrobial susceptibility testing to be performed.

Lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis caused by

Chlamydia trachomatis requires a prolonged course of

therapy. Either doxycycline or a macrolide is recom-

mended, although there are no clinical trials to guide the

use of macrolides. There is also interest in fluoroquinol-

ones, although again, trial data are lacking.

Mycobacterial infection

Gastrointestinal infection with M. tuberculosis is treated

in the same fashion as pulmonary tuberculosis, initially

using a four drug regimen involving rifampicin, isonia-

zid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol dosed according to

patient weight for 2 months followed by a further

4 months of rifampicin and isoniazid.97 Following cul-

ture of M. tuberculosis, sensitivity testing should be per-

formed to refine the antituberculous regimen if

resistance is detected. Treatment of MAI consists of a

macrolide, rifamycin and ethambutol given three timesweekly for noncavitary disease and daily with or without

an aminoglycoside for cavitary disease.98 Antimycobacte-

rial therapy for MAI should not be stopped until

immune reconstitution with ART has occurred.99

Protozoal and fungal infections

Despite a drive to diagnose HIV earlier and the introduc-

tion of ART, protozoal infections continue to cause diar-

rhoeal disease in HIV-infected patients and they frequently

present a therapeutic challenge. The drugs of choice for

Giardiasis are metronidazole (2 g ⁄ day for 3 days) or tini-dazole (2 g once), with a cure rate of 73–100%.100 Nitazox-

anide is an alternative with an 81% success rate. 101 There

are inadequate and conflicting trials of specific therapy

for cryptosporidiosis with both nitazoxanide and

paroromycin. A recent Cochrane meta-analysis of seven

trials including 130 adults with HIV concluded that

although nitaxozanide reduces the load of parasites and

may be useful in immunocompetent individuals, the effect

was not significant for HIV-infected patients. Despite this,

Review: diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603 597ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

13/18

the use of nitaxozanide should be considered in very sick

HIV-infected patients with Cryptosporidiosis.102 Trials of

paroromycin have included even fewer HIV-infected

patients and the same meta-analysis found no statistically

significant effect. Further trials are unquestionably war-

ranted; however, the mainstay of treatment is effective

immune reconstitution with ART.103–105

The treatment of Isoporiasis and Cyclospora is more

straightforward. Both pathogens are susceptible to co-

trimoxazole, which may resolve symptoms in up to

100% of patients.106 In the case of intolerance or allergy

to sulphonamides, ciprofloxacin may be used, although it

is less effective, resolving only 87% cases.106

The main specific therapy for microsporidiosis is alben-

dazole. While Encephalitozoon intestinalis responds well to

albendazole 400 mg b.d. for 3 weeks, which caused clinical

resolution and parasite clearance in 4 ⁄ 4 patients in one

study,107 Enterocytozoon bieneusi does not. Albendazole

should still be tried, but supportive therapy with fluids andearly initiation of ART are crucial. As with cryptosporidio-

sis, immune reconstitution can lead to complete clearance

of microsporidia.103

Anti-viral therapy

Specific anti-viral therapy is available for CMV colitis

using IV ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir. Alternatively

foscarnet and cidofovir have been approved, but there

are no clinical trials to support a specific therapy for

CMV colitis. Immune reconstitution is an essential com-

ponent of treating CMV disease.

Prophylactic therapy

Cotrimoxazole remains a useful prophylactic agent in

HIV-infected patients. While in the developed world, it is

primarily used to prophylax against PCP and toxoplasma

encephalitis in the profoundly immunosuppressed (plasma

CD4 count less than 200 · 109 ⁄ L), it will also prevent isos-

pora diarrhoea.108 Cotrimoxazole is used much earlier in

the course of HIV in developing countries (plasma CD4

count less than 500 · 109 ⁄ L). This is in part due to its

prophylactic role against malaria, but it also prevents diar-rhoea.109

Secondary prophylaxis is recommended by the CDC

for the prevention of recurrent nontyphoid Salmonella

sepsis, but not for other enteric bacterial pathogens.108

Antiretroviral therapy

The treatment of HIV was revolutionised initially by the

introduction of Zidovudine ⁄ AZT and subsequently by

combination ART. Now multiple classes of ARVs are

available and what was once a terminal illness should

now be regarded as a chronic, treatable medical disorder.

Current regimens for ARV naive patients are well toler-

ated with low pill burdens. In the early days of HIV

therapy, the consensus was that treatment was unneces-

sary until the CD4 count fell to around 200 · 109 ⁄ L.

This decision was based on the perceived risk of OIs at

CD4 counts of 200–400 · 109 ⁄ L or less, the severe side

effects of early regimens and the cost of ART. Current

guidelines recommend that ART should start before the

CD4 count falls below 350 · 109 ⁄ L,110 with many experts

advocating even earlier treatment,111 although this

remains controversial.

Antiretroviral therapy rapidly reduces plasma HIV

viral load enabling the CD4+ T-lymphocyte population

to reconstitute and there is good evidence that this

reduces chronic diarrhoea in HIV-infected individuals,

often very rapidly.112 Sampling of gut tissue reveals a

rapid fall in viral load,112 which suggest that the virushas a central role in HIV-associated diarrhoea. There is

robust evidence of both a general reduction in gastroin-

testinal OIs113 with the introduction of ART and of

improvement in the outcome from infection with specific

OIs. Infections caused by pathogens which have no spe-

cific treatment may resolve following the introduction of

ART including cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis,103

while the treatment of other OIs for which specific ther-

apy is available (i.e. CMV colitis) is enhanced by the

introduction of ART.27 Lastly, recurrence of invasive bac-

terial infections such as Salmonellosis has been shown tocease following introduction of ART.114

Despite the clinical improvement that is frequently

seen, the picture at a GI cellular level is more complex.

The completeness of gastrointestinal reconstitution is

controversial with some studies showing good CD4 T-

cell repletion, while others have suggested that it is both

poor and much slower than the improvement in plasma

CD4 count40 and that in the long term, patients with

poor GI CD4 reconstitution have ongoing immune acti-

vation. One possible explanation for this is the

observation that some GI CD4 cells have been observedto produce HIV years after initiation of ART.115, 116 A

second possibility is that fibrotic damage to GI lymphoid

tissue prior to initiation of ART may be such that the

ability to replace CD4 T-cells in the GIT is permanently

impaired40 and early initiation of ART certainly fosters a

more complete CD4 reconstitution in the GIT.115, 116

Although gut mucosal CD4 depletion does not com-

pletely reconstitute following antiretroviral therapy, pos-

sibly because of the deposition of collagen in GALT,117

N. A. Feasey et al.

598 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

14/18

many of the functional consequences, including perme-

ability defects, are measurably reversed.118

Symptomatic treatment of chronic diarrhoea

Chronic diarrhoea in Western populations is now

increasingly rare due to the introduction of ART early in

the course of HIV infection. Despite exhaustive investiga-

tion of diarrhoea and initiation of ART, diarrhoea may

persist or even result from HIV therapy and empirical

treatment may be required. Antimotility agents (lopera-

mide, diphenoxylate and codeine) and adsorbents (bis-

muth subsalicylate, kaolin ⁄ pectin and attapulgite) have

anecdotally been found to be useful. Antimotility agents

increase gut transit time, giving more time for fluid reab-

sorption and while narcotic analgesics should be avoided

because of their addictive nature, loperamide and di-

phenoxylate may be useful, although studies are lacking.

A recent Cochrane review highlighted the lack of evi-

dence for these agents and the need for further stud-ies.119 Cholestyramine may be beneficial if diarrhoea is

caused by malabsorption of bile salts.120 Other measures

studied include zinc or other micronutrient supplementa-

tion, mesalazine (mesalamine) and curcumin. Rando-

mised controlled trials of zinc supplementation121 and

mesalazine122 in adults revealed no benefit, while a small

study of the turmeric extract curcumin revealed a benefit

in five of six patients.123 A Cochrane review has con-

cluded that micronutrient supplementation offers no

reduction in morbidity (including diarrhoea) or mortality

among HIV-infected adults.124 One more recent study of broader micronutrient supplementation did not result in

significant reduction in diarrhoea, although there was a

very modest reduction in severe infectious diarrhoea.125

Supplementation with vitamin A and zinc, however, has

failed to significantly reduce gut permeability or markers

of microbial translocation.126 Although octreotide has

been used for symptomatic control of diarrhoea in HIV

enteropathy, the results of trials are inconsistent.127–129

In the case of HIV-related colitis, thalidomide has been

used with success in individual patients,52 but randomised

controlled trials are lacking. Typhlitis or caecitis has beensuccessfully managed with bowel rest, IV fluids and broad

spectrum antibiotics.130 Discussion of chemotherapy for

mitotic lesions is beyond the scope of this review, but the

expert opinion of an oncologist should be sought in

the case of discovery of an HIV-related malignancy as the

cause of diarrhoea and it should be remembered that tight

control of HIV viraemia forms an essential part of the

treatment of these cancers.

CONCLUSIONS

Human immunodeficiency virus infection impacts upon

the gastrointestinal tract in a variety of ways and there is

an incomplete understanding of the mechanisms by which

it does this. The aetiology of diarrhoea in HIV infection is

diverse and includes the direct effects of the virus upon the

GIT, infection with both obligate and opportunistic ente-

ropathogens, malignant and other ‘non-infectious’ causes

and as a consequence of anti-viral therapy. In addition,

HIV-infected patients are still susceptible to unrelated but

common causes of diarrhoea including irritable bowel dis-

ease and drug side effects. A multidisciplinary approach to

diagnosis and management is therefore best practice and

in the best interests of the patient.

Faecal microbiology remains the principal and first-

line investigation for diarrhoea in HIV-infected patients.

Tests typically available routinely include microscopy,

culture and enzyme immunoassays. In recent years, the

cost of genome sequencing technology has plummeted

and its increasing availability is revolutionising microbi-

ology. Failure to detect pathogens by currently available

diagnostic microbiology may lead to a need for complex

radiology or the judicious use of endoscopy and tissue

biopsy.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is generally acknowledged to

be an appropriate first-line investigation in stool-negative

cases, and full colonoscopy with visualisation and biopsy

of the terminal ileum, rather than gastroduodenoscopy is

generally a reasonable second-line endoscopic investiga-

tion. Radiological findings are often nonspecific but use-ful to detect disease severity, distribution and

complications, and some HIV-related malignancies.

While current research suggests that people diagnosed

with HIV infection today might expect to live a normal

life if adherent to their therapy, ARVs may themselves

cause diarrhoea and further research is needed to opti-

mise drug dosage, particularly with protease inhibitors. A

good evidence-base for symptomatic management of

HIV-related diarrhoea is also lacking. The greatest bur-

den of HIV infection falls on Sub-Saharan African coun-

tries where there are limited diagnostic facilities.National and regional prevalence studies of enteropatho-

gens are needed, both to inform regional and national

treatment strategies and to highlight the true burden of

disease attributable to neglected or newly discovered

pathogens. The intestinal parasites also number among

the neglected tropical diseases and new therapies for

these pathogens are urgently needed for both HIV-

infected and uninfected patients.

Review: diarrhoea in HIV-positive patients

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603 599ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

15/18

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of personal interests: None. Declaration of

funding interests: No financial support was received for

the preparation of this manuscript. Dr Feasey is supported

by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship.

REFERENCES1. Serwadda D, Mugerwa RD, Sew-

ankambo NK, et al. Slim disease: a new disease in Uganda and its associationwith HTLV-III infection. Lancet 1985;2: 849–52.

2. Thomas PD, Forbes A, Green J, et al.Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea, 2nd edition. Gut 2003; 52(Suppl. 5): v1–15.

3. Antony MA, Brandt LJ, Klein RS, Bern-stein LH. Infectious diarrhea in patientswith AIDS. Dig Dis Sci 1988; 33: 1141–6.

4. Connolly GM, Shanson D, HawkinsDA, Webster JN, Gazzard BG. Non-

cryptosporidial diarrhoea in humanimmunodeficiency virus (HIV) infectedpatients. Gut 1989; 30: 195–200.

5. Colebunders R, Lusakumuni K, NelsonAM, et al. Persistent diarrhoea in ZairianAIDS patients: an endoscopic and histo-logical study. Gut 1988; 29: 1687–91.

6. Kelly P, Todd J, Sianongo S, et al. Sus-ceptibility to intestinal infection anddiarrhoea in Zambian adults in relationto HIV status and CD4 count. BMC Gastroenterol 2009; 9: 7.

7. Kotler DP. Characterization of intestinaldisease associated with human immu-nodeficiency virus infection and

response to antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 1999; 179(Suppl. 3): S454–6.

8. Ullrich R, Zeitz M, Riecken EO. Entericimmunologic abnormalities in humanimmunodeficiency virus infection. Se-min Liver Dis 1992; 12: 167–74.

9. Clayton F, Snow G, Reka S, Kotler DP.Selective depletion of rectal lamina pro-pria rather than lymphoid aggregateCD4 lymphocytes in HIV infection.Clin Exp Immunol 1997; 107: 288–92.

10. Monkemuller KE, Lazenby AJ, Lee DH,Loudon R, Wilcox CM. Occurrence of gastrointestinal opportunistic disordersin AIDS despite the use of highly active

antiretroviral therapy. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50: 230–4.

11. Gordon MA, Banda HT, Gondwe M,et al. Non-typhoidal salmonella bactera-emia among HIV-infected Malawianadults: high mortality and frequentrecrudescence. AIDS 2002; 16: 1633–41.

12. Tee W, Mijch A. Campylobacter jejunibacteremia in human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected patients: comparison of clinicalfeatures and review. Clin Infect Dis1998; 26: 91–6.

13. Sorvillo FJ, Lieb LE, Waterman SH.Incidence of campylobacteriosis among patients with AIDS in Los AngelesCounty. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1991; 4: 598–602.

14. Nadelman RB, Mathur-Wagh U,Yancovitz SR, Mildvan D. Salmonellabacteremia associated with the acquiredimmunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Arch Intern Med 1985; 145: 1968–71.15. Smith PD, Macher AM, Bookman MA,

et al. Salmonella typhimurium enteritisand bacteremia in the acquired immu-nodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med

1985; 102: 207–9.16. Gruenewald R, Blum S, Chan J. Rela-

tionship between human immunodefi-ciency virus infection and salmonellosisin 20- to 59-year-old residents of New York City. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 18:358–63.

17. Sanchez TH, Brooks JT, Sullivan PS,et al. Bacterial diarrhea in personswith HIV infection, United States,1992–2002. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41:1621–7.

18. de la Monte SM, Hutchins GM. Follicu-lar proctocolitis and neuromatoushyperplasia with lymphogranuloma ven-

ereum. Hum Pathol 1985; 16 : 1025–32.19. van Nieuwkoop C, Gooskens J, Smit

VT, et al. Lymphogranuloma venereumproctocolitis: mucosal T cell immunity of the rectum associated with chlamyd-ial clearance and clinical recovery. Gut 2007; 56: 1476–7.

20. Burgers WA, Riou C, Mlotshwa M,et al. Association of HIV-specific andtotal CD8 + T memory phenotypes insubtype C HIV-1 infection with viralset point. J Immunol 2009; 182: 4751–61.

21. Horsburgh CR Jr. Mycobacterium avi-um complex infection in the acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 1332–8.

22. Wallace JM, Hannah JB. Mycobacteriumavium complex infection in patientswith the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. A clinicopathologic study.Chest 1988; 93: 926–32.

23. Goodgame RW. Understanding intesti-nal spore-forming protozoa: cryptospo-ridia, microsporidia, isospora, andcyclospora. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124:429–41.

24. Stark D, Barratt JL, van Hal S, MarriottD, Harkness J, Ellis JT. Clinical signifi-cance of enteric protozoa in the immu-nosuppressed human population. Clin

Microbiol Rev 2009; 22: 634–50.25. Gertler SL, Pressman J, Price P, Brozin-

sky S, Miyai K. Gastrointestinal cyto-megalovirus infection in a homosexualman with severe acquired immunodefi-ciency syndrome. Gastroenterology 1983;85: 1403–6.

26. Dieterich DT, Rahmin M. Cytomegalo- virus colitis in AIDS: presentation in 44patients and a review of the literature. J

Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1991;4(Suppl. 1): S29–35.

27. Salzberger B, Hartmann P, Hanses F,et al. Incidence and prognosis of CMVdisease in HIV-infected patients beforeand after introduction of combinationantiretroviral therapy. Infection 2005;33: 345–9.

28. Grohmann GS, Glass RI, Pereira HG,et al. Enteric viruses and diarrhea inHIV-infected patients. Enteric Opportu-nistic Infections Working Group. N Engl

J Med 1993; 329: 14–20.29. Veugelers PJ, Kaldor JM, Strathdee SA,

et al. Incidence and prognostic signifi-

cance of symptomatic primary humanimmunodeficiency virus type 1 infectionin homosexual men. J Infect Dis 1997;176: 112–7.

30. Schroder U, Waller V, Kaliebe T, AgathosM, Breit R. Acute primary stage of HIVinfection with documented seroconver-sion. Hautarzt 1994; 45: 29–33.

31. Uppal B, Kashyap B, Bhalla P. Entericpathogens in HIV ⁄ AIDS from a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Community Med 2009; 34: 237–42.

32. Vaishnavi C, Kaur S, Prakash S. Specia-tion of fecal Candida isolates in antibi-otic-associated diarrhea in non-HIV

patients. Jpn J Infect Dis 2008; 61:1–4.

33. Casotti JA, Motta TQ, Ferreira CU Jr,Cerutti C Jr. Disseminated histoplasmo-sis in HIV positive patients in EspiritoSanto state, Brazil: a clinical-laboratory study of 12 cases (1999–2001). Braz J Infect Dis 2006; 10: 327–30.

34. Connolly GM, Forbes A, Gazzard BG.Investigation of seemingly pathogen-negative diarrhoea in patients infectedwith HIV1. Gut 1990; 31: 886–9.

N. A. Feasey et al.

600 Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 587–603ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

-

8/20/2019 APT Final Published Hiv Diarrhoea Revision

16/18

35. Orenstein JM, Chiang J, Steinberg W,Smith PD, Rotterdam H, Kotler DP.Intestinal microsporidiosis as a cause of diarrhea in human immunodeficiency

virus-infected patients: a report of 20cases. Hum Pathol 1990; 21: 475–81.

36. Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV,et al. Gastrointestinal tract as a majorsite of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral

replication in SIV infection. Science1998; 280: 427–31.

37. Sankaran S, George MD, Reay E, et al.Rapid onset of intestinal epithelial bar-rier dysfunction in primary humanimmunodeficiency virus infection isdriven by an imbalance betweenimmune response and mucosal repairand regeneration. J Virol 2008; 82:538–45.

38. Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW,et al. Microbial translocation is a causeof systemic immune activation inchronic HIV infection. Nat Med 2006;12: 1365–71.

39. Gordon SN, Cervasi B, Odorizzi P,et al. Disruption of intestinal CD4+ Tcell homeostasis is a key marker of sys-temic CD4+ T cell activation in HIV-infected individuals. J Immunol 2010;185: 5169–79.

40. Brenchley JM, Douek DC. HIV infec-tion and the gastrointestinal immunesystem. Mucosal Immunol 2008; 1:23–30.

41. Batman PA, Miller AR, Forster SM,Harris JR, Pinching AJ, Griffin GE.Jejunal enteropathy associated withhuman immunodeficiency virus infec-tion: quantitative histology. J Clin

Pathol 1989; 42: 275–81.42. Kotler DP, Gaetz HP, Lange M, Klein

EB, Holt PR. Enteropathy associatedwith the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1984; 101:421–8.

43. Cello JP, Day LW. Idiopathic AIDSenteropathy and treatment of gastroin-testinal opportunistic pathogens. Gastro-enterology 2009; 136: 1952–65.

44. Bjarnason I, Sharpstone DR, Francis N,et al. Intestinal inflammation, ilealstructure and function in HIV. AIDS1996; 10: 1385–91.

45. Sharpstone D, Neild P, Crane R, et al.

Small intestinal transit, absorption, andpermeability in patients with AIDS withand without diarrhoea. Gut 1999; 45:70–6.

46. Keating J, Bjarnason I, SomasundaramS, et al. Intestinal absorptive capacity,intestinal permeability and jejunal his-tology in HIV and their relation todiarrhoea. Gut 1995; 37: 623–9.

47. Kapembwa MS, Fleming SC, Sew-ankambo N, et al. Altered small-intesti-nal permeability associated withdiarrhoea in human-immunodeficiency-

virus-infected Caucasian and Africansubjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991; 81: 327–34.

48. Knox TA, Spiegelman D, Skinner SC,Gorbach S. Diarrhea and abnormalitiesof gastrointestinal function in a cohortof men and women with HIV infection.

Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: