Volume XVIII • Number 2 • 2015 • For Artists and Cultural Workers • ISSN 0119-5948 Official Newsletter of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts Inscribed for Posterity

AGUNG No 2 (March-June) 2015_opt

Dec 14, 2015

AGUNG

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Volume XVIII • Number 2 • 2015 • For Artists and Cultural Workers • ISSN 0119-5948

Official Newsletter of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts

Inscribed for Posterity

Vol. XVIII, No. 2March-June 2015ISSN 0119-5948

The agung is a knobbed metal gong of the Philippines used in various communal rituals. Suspended in the air by rope or metal chains, the musical instrument is also employed by some indigenous groups as a means to announce community events, and as an indicator of the passage of time.

Agung is published bimonthly by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Cover shows the Old Tagalog baybayin documents of University of Santo Tomas Archives declared a National Cultural Treasure

This issue of Agung captures an auspicious and celebratory time in the arts and culture landscape of the country as there are several developments that we can be indeed grateful for.

First, our literatures are given their deserved spotlight, not only this year but in the years to come with the signing of Proclamation No. 968, which declares April as Buwan ng Panitikang Filipino or National Literature Month. With this gesture, the whole nation will bestow on our writers and their works that very much deserved salutation. Literature has been crucial in shaping our personal lives, our communities and the nation.

Not exactly literature, but a system of writing was declared National Cultural Treasure. The baybayin documents of the University of Santo Tomas and their recognition inspire us to take pride in our own culture, which is advanced enough to have its own systems of writing.

Concerning another National Cultural Treasure, the Metropolitan Theater of Manila has finally come under the wings of the NCCA. After many years of sporadic restoration and neglect, this heritage landmark will see a rebirth as a center for the arts as plans are underway for its rehabilitation and conservation.

On the other hand, a part of our intangible cultural heritage, specifically the Christian traditions, is vibrant and well. The Filipino is a very spiritual people, and it is no surprise that some groups, particularly, the lowland ones, had embraced Christianity. Not only that, the Filipino has imbued it with such character and color that the religion becomes effervescent and interesting. It is not enough that rituals are somber and serious; they must include dancing and songs, engaging the whole community. Devotion is not only private but public as well, as people gather and connect to each other in public ceremonies and celebrations. A celebration of a Philippine Christian milestone, Kaplag 450 not only traces the devotion to the Santo Nino and the start of Christianity in the Philippines. It is also a reflection of this devotion made alive with dancing and songs, resulting in the spectacular Sinulog Festival of Cebu as well as other feast day celebrations in honor of the Santo Niño.

Even in the most elegiac of Christian occasions like Lent, Filipinos still gather together and mount colorful commemorations that not only gather the community but draw people from other places to join as well, such as the case of the Lenten rituals and traditions of Paete, Laguna.

And in line with the Yugyugan event, we dance for ourselves, for the community, for heritage and for the spirit that unites us as a nation. We dance to connect, to heal and to inspire.

FELIPE M. DE LEON, JR.

FELIPE M. DE LEON, JR.chairman

ADELINA M. SUEMITHoic-executive director

MARLENE RUTH S. SANCHEZ, MNSAdeputy executive director

Rene Sanchez Napeñaseditor-in-chief

Roel Hoang Maniponmanaging editor

Mervin Concepcion Vergara art director

Marvin Alcarazphotographer

Leihdee Anne CabreraManny AraweAlinor MaquedaMay Corre TuazonRoezielle Joy IglesiaRandolf Claritopaio staff

About the cover

The National Commission for Culture and the Arts

As the government arm for culture and the arts, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) is the overall policy-making, coordinating,

and grants-giving agency for the preservation, development and

promotion of Philippine arts and culture; and executing agency for the policies it formulates; and an agency

tasked to administer the National Endowment Fund for Culture and

the Arts (NEFCA). The NCCA traces its roots to the Presidential Commission

for Culture and the Arts (PCCA), which was created when President Corazon Aquino signed Executive Order No. 118 on January 30, 1987, “mindful of the fact that there is a need for a

national body to articulate a national policy on culture, to conserve and promote national heritage, and to guarantee a climate of freedom, support and dissemination for all forms of artistic and cultural

expression.” On April 3, 1992, President Aquino

signed Republic Act No. 7356 creating the NCCA and establishing the NEFCA, a result of over two years of legislative

consultations among government and private sector representatives. The bill was sponsored by senators Edgardo J. Angara, Leticia Ramos-Shahani, Heherson T. Alvarez and

congressman Carlos Padilla.The NCCA Secretariat, headed by the

executive director and headquartered at the historic district of Intramuros,

provides administrative and technical support to the NCCA and other units, and delivers assistance to the culture and arts community and the public.

Emilie V. Tiongcoeditorial consultant

MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN2 | Agung March - May 2014

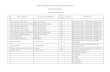

The National Archives of the Philippines (NAP) unveiled a marker for the two Old Tagalog baybayin documents of the Uni-versity of Santo Tomas (UST) Archives, declaring them a National Cultural Treasure (NCT), on November 13, 2014, at the Miguel de Benavides Library. This was the first time NAP has declared a Na-tional Cultural Treasure and the first for a paper document.

The unveiling was graced by NAP executive director Victori-no Mapa Manalo; National Artist for literature and Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino chairman Virgilio Almario; NCCA chairman Fe-lipe de Leon Jr.; UST rector Rev. Fr. Herminio V. Dagohoy, O.P.; and UST archivist Regalado Trota Jose.

Prior to the unveiling of the marker, the UST baybayin documents were first declared NCT at the Second Baybayin Conference, the An-cient and Tradition Scripts in the Philippines. Hosted by the National Museum of the Philippines (NM), the conference was held at the Ayala Theater, Museum of the Filipino People, on August 22, 2014, in con-junction with the nationwide celebration of Buwan ng Wika.

The First Baybayin Conference was held on December 13, 2013, and presented the discovery of Monreal Stones in Ticao Island, Mas-bate, to the public. For the second conference, the objectives were to present updates on the studies made on Monreal Stones and other artefacts with ancient scripts, to intensify awareness on the cultural importance of the baybayin; to raise awareness of the importance of cultural heritage and the need for its protection; to share knowl-edge; and to provide a forum for researchers and students on how to preserve and protect the Filipino cultural heritage. The conference was participated in by more than sixty representatives from NAP, UST, National Library, KWF, San Beda Ayala, Siliman University, University of the Philippines, Normal University of the Philippines, NCCA, Sanghabi Group, Philippine Daily Inquirer, and the Na-

UST Baybayin Documents Declared National Cultural TreasureInvaluable Imprints

tional Museum personnel from the Archaeology, Anthropology and Chemistry and Conservation Laboratory Divisions.

Distinguished anthropologists and researchers in the field of an-cient and traditional scripts in the Philippines presented their paper including Dr. Bonifacio F. Comandante, Jr of the Siliman University, who gave updates on the Monreal Stones, sulat baybayin of Mind-anao, and present use of baybayin; Dr. Teresita B. Obusan of Bahay Nakpil, who said that there is a need to conduct an extensive and intensive research on ancient and traditional scripts in the Philippines and the baybayin is a medium used by our ancestors in giving mean-ing to things, objects and events; Emmanuel S. Castro, who told the accomplishment of Sanghabi in 15 years of research, presentation and ritual performance; Adelina Villena, who discussed the case of the il-legal extraction of stalagmite in Guri Cave; Melissa May Cardenas, who combined the art of writing ambahan, poetry from of Hanunuo and Buhid, using baybayin; Leo Batoon, who presented the National Museum project on the conservation of Tagbanua/Pala’wan syllabic writing; and Dr. Ramon Guillermo, who attempted to qualify or even refute the notion that texts written in traditional Tagalong baybayin are necessarily difficult or even impossible to read, and made a re-newed assertion of a corollary hypothesis regarding the strong possibil-ity of a relationship between Bugis-Makasar and Philippine syllabaries.

The public declaration of UST baybayin documents served as the highlight of the conference, led by Michael C. Francisco. Jose presented a paper on their significance.

Baybayin is a general Filipino or Tagalog word for “script,” “writ-ing” or “syllabary,” and now refers to the Old Tagalog abugida. The Philippines has several baybayins, including the Palaw’an, Tagbanua, Hanunuo Mangyan and Buhid Mangyan.

The UST baybayin documents are two deeds of sale of land,

UST archivist Regalado Trota Jose guides NCCA chairman Felipe de Leon Jr., and KWF chairman Virgilio Almario in

viewing the baybayin documents. /Photo by Marvin Alcaraz

transacted in 1613 (labelled as Document A) and 1625 (labelled as Document B).

According to Academia, the UST international bulletin (Octo-ber 2014), “Document A documents the sale of tubigan (irrigated land) by Doña Catalina Baycan, a maginoo or principal of Tondo, to Don Andres Capiit of Dilao, a district in the vicinity of today’s Manila City Hall. Document B documents the sale of irrigable land in the area of Mayhaligue, most possibly the area around the De-partment of Health in Santa Cruz, Manila, by Doña Maria Silang, a maginoo of Tondo, to Doña Francisca Longgad, a maginoo of Dilao.

“Document A is dated February 15, 1613, while Document B is dated December 4, 1625. The second paper was previously dated to 1635, until further research showed that in Old Tagalog, according to Fr. Blancas and Tomas Pinpin, expressing a number from twenty onward to another number was achieved by counting the next high-er decade and affixing the lower number. For example, 42 would be written ‘micalimandalawa’ (two towards the fifth decade), and so forth. Thus, ‘micatlong lima’ was then correctly read as 25, not 35.

“Don Andres Capiit, who bought the land in Document A, married Doña Francisca Longgad, who bought the land in Docu-ment B. Capiit must have died between 1613 and 1625, at which time Francisca married Don Luis Castilla. In 1629 Luis Castilla sold

some land to UST, which occasioned some contestation. Castilla therefore showed as proof of ownership Documents A and B.

“When UST acquired this land, the proper documents passed on to form a hefty volume of 17th century papers in the UST Ar-chives. They were both summarized in Spanish in 1629, which pro-vided us with a baybayin Rosetta Stone,’ an invaluable tool to read-ing these documents.

“A pioneering study on baybayin in UST was made by Ig-nacio Villamor and Norberto Romualdez, both Thomasians, in 1918, which was revised in 1922. Villamor became the first Fili-pino president of the University of the Philippines (1915 to 1918), while Romualdez was eventually made chairman of the Philippine Commonwealth’s Committee on National Language. The study was deepened by the work of Fr. Alberto Santamaria, O.P., archivist of UST, who published his work in 1938 in the UST journal Unitas.

“The UST baybayin documents provide us with an insight on how much more prevalent was the use of baybayin. Previously, it was generally thought that baybayin was limited to writing love poems, accounting, and signing papers. The documents give us a glimpse of life and commerce in early 17th century Manila, at a time when UST was still a fledgling school. Significantly, they also demonstrate the involvement of women in business, selling and buying land in this instance.”

The UST baybayin documents are considered the “longest and most complete documents completely handwritten in baybayin,” part of a compilation of baybayin documents regarded as the “big-gest collection of extant ancient baybayin scripts in the world.” They are also the oldest known deeds of sale for land in the Philippines.

A National Cultural Treasure is described as “a unique object found locally, possessing outstanding historical, cultural, artistic and/or scien-tific value which is significant and important to this country and nation” (Republic Act 4846 as amended by Presidential Decree 374).

The documents are the fifth objects found in the UST campus to be declared NCTs. The four others include the UST Main Building, the Arch of the Centuries, the Central Seminary building, and UST’s open spaces. The UST is the only school in the country to have NCTs.

Due to their fragility, the documents are stored at the UST archives and are unavailable for public viewing. Replicas, however, may be viewed at the archives’ office on the fifth floor of the UST Miguel de Benavides Library. The baybayin documents were first shown in public during the tricentennary of the university in 1911. That same year, the documents were first published in Libertas, a daily newspaper published by the university.

Senator Loren Legarda renewed her call for the promotion of baybayin by using it in government logos, public signage and even in local product labels, during the fourth Baybayin Festival Rizal, which was organized by Taklobo Baybayin Inc., Baybayin Buhayin, the Department of Education (DepEd) and the province of Rizal, on November 22, 2014, at the Ynares Center, Antipolo City.

The event was attended by teachers and students from public and private elementary and high schools in the DepEd Division of Rizal and Antipolo. Legarda also shared that she has filed measures in the Senate that aim to promote and preserve baybayin.

Senate Bill No. 1899 mandates all government agencies, departments and offices to incorporate Baybayin in their official logos.

“All government agencies and offices must take the lead to further promote Filipino culture and traditions, strengthen Filipino identity, and instill the same in everyday life. The logos and seals of government agencies and offices should not only reflect the emblems of their functions and duties but also pride in Filipino heritage and traditions,” said Legarda.

Some of the government offices and agencies that have already incorporated baybayin in their official logos include the National Museum of the Philippines, Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, the National Library, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the National Archives of the Philippines, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), and the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP).

Meanwhile, Senate Bill No. 2440 aims to declare baybayin as the National Writing Script of the Philippines and mandates the NCCA to lead the promotion, protection, preservation and conservation of the baybayin.

The measure also mandates local food manufacturers to inscribe baybayin and their translation on containers or labels; local government units (LGUs) to use baybayin in their signage for street names, public facilities, among others; and newspaper and magazine publishers to include baybayin translation of their official name.

Moreover, reading materials about baybayin will be distributed to all public and private educational institutions and all government and private agencies and offices to instill awareness of the declaration of baybayin as the national writing system.

OTHER GOVERNMENT EFFORTS

The unveiling of the marker declaring the baybayin documents of UST as National Cultural Treasure was led by NCCA chairman Felipe de Leon Jr., National Archives of the Philippines executive director Victorino Mapa Manalo, UST rector Rev. Fr. Herminio V. Dagohoy and UST archivist Regalado Trota Jose. /Photo by Marvin Alcaraz

4 Agung • Number 2 • 2015

The new bronze statue of 19th-century Tagalog poet Francisco “Balagtas” Baltazar was unveiled in Orion, Bataan, made by sculptor Julie Lluch. /Photo by Roel Hoang Manipon

Intensifying the Light of LiteratureThe Commemoration of Balagtas and the Launch of National Literature Month

Manila Bay, from the vantage point of Roxas Boulevard and the districts of Ma-late and Ermita, is where the sun sets most beautifully in the sprawling metropolis. But in the town of Orion in Bataan, a province northwest of the Philippine capital and which hugs the northern portion of the bay, the sun disperses its first light. It lightly gilds the shore of Wawa, a coastal barangay of Orion, where the neighborhood children play among the ashen sand; the families and lovers watch the sun rise on the breakwater; and the fishermen cast their nets out in the sea.

On the early morning of March 30, 2015, the most beautiful monument to Francisco “Balagtas” Baltazar first saw golden light here, as it was unveiled in the presence of cultural and local government officials including National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) chairman Felipe de Leon, Jr.; National Artist for lit-erature and chairman of the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF) Virgilio Almario; Antonio Raymundo, Jr., mayor of Orion; and Albert S. Garcia, Bataan governor, stir-ring up the usually quiet neighbourhood and indicating the importance of the event.

The 19th century poet is widely consid-ered the greatest of poets in Filipino and one of the greatest writers in the Philip-pines, whose metrical romance or awit Flo-rante at Laura is included in the high school curriculum. While regarded a hero, he was perhaps the least commemorated and there was no decent monument of him.

The recently unveiled monument was “para tunay na mailuklok natin sa tumpak na

Text and photos by Roel Hoang Manipon

dambana ng karangalan ang ating bayaning manunulat” (to truly place our writer-hero in his right shrine of honor), according to Almario.

KWF commissioned Julie Lluch to do the monument. The prominent sculptor did the monuments of Apolinario Mabini for the 150th birth anniversary celebration, which is now in Tanauan, Batangas; Carlos P. Romulo along United Nations Avenue, Manila; Jose Abad-Santos and Cayetano Arellano on Padre Faura Street, Manila; and President Manuel L. Quezon in the province of Quezon. For Balagtas, she took inspira-tion, upon the suggestion of Almario, from the depiction of Balagtas by National Art-ist for visual arts Carlos “Botong” Francisco in his mural that was originally installed at the Manila City and now owned by the Na-tional Museum of the Philippines. The new bronze monument portrays the poet seated beside a table, a quill in one hand and look-ing at the sea, seemingly in deep thought.

Surrounding the monument, a park was under construction, including part of the bay still to be reclaimed. The Hardin ni Balagtas, or the Garden of Balagtas is en-visioned to serve as a “cultural park” with native plants and trees. When the reclama-tion and landscaping are finished, Almario wished it to be national park, a destination for tourists and literature lovers. A library is envisioned so that the park is “hindi lang hardin ng pagmamahalan kundi hardin din ng karunungan” (not only a garden of love but also a garden of knowledge) and those who will visit “‘di lang mamasyal, para rin mag-aral and magbasa.” (not only lounge

around but also to study and read) A big plan of the KWF and the municipal gov-ernment are finding the remains of Balagtas and their re-internment at the park. It is a popular belief in Orion that the Balagtas re-mains are buried at the Saint Michael the Arcangel Parish Church, near the altar.

“Gusto naming itangi ng buong Filipi-nas ang ating manunulat,” (We wish that the whole Philippines will distinguish our writer) Almario said. “Kung mapapansin mo kasi, ang halos lahat ng deklaradong national heroes ng Filipinas ay puro mga patriots, mga martir, mga heneral, mga napatay para sa bayan. Ang gusto natin ngayon ay magkaroon din tayo ng isang modelo sa ating mga ka-bataan na isang bayani na kahahangaan da-hil sa kanyang malikhaing talino, hindi nag-pakamatay sa bayan, hindi naghirap sa kung anuman para sa bayan, ngunit inihandog ang kanyang talino, ang kanyang dakilang talino, para sa pagsulong ng kamulatan ng ating mga kababayan. At nais naming na si Balagtas ang maging modelo ng gayong uri ng bayani.” (Because you would notice, almost all of the declared national heroes of the Philip-pines were patriots, martyrs, generals, those killed for the country. What we want now is to also have a model for our youth, a hero admired because of his creative genius, not because he died or suffered for the country, but he offered his talent, his great talent, for the advancement of our countrymen’s consciousness. We wish Balagtas to be the model for that kind of hero.)

Almario said these to hundreds of young participants of the youth camp Kampo Balagtas, which immediately began at the

6 Agung • Number 2 • 2015

Intensifying the Light of LiteratureOrion Elementary School after the unveil-ing of the statue. These two events were held in commemoration of the 227th birth anni-versary of Balagtas or the Araw ni Balagtas (Balagtas Day), which falls on April 2. Since becoming KWF chairman, Almario made it a point to pay tribute to Balagtas in a sig-nificant way. Last year, he spearheaded com-memorative events in three places closely as-sociated to Balagtas, including Orion. The town, then called Udyong, is said to be close to Balagtas’s heart. Here, he wrote some of his masterpieces and died on February 20, 1862.

“Ito pa lamang ang ikalawang pagkakata-on ng paglalakbay ng KWF dito sa Bataan,” (This is just the second time KWF trav-eled to Bataan) he related. “Naisip namin ito noong nakaraang taon upang kilalanin ang pangyayari na kung tutuusin kahit ipi-nanganak sa Bulakan, kahit sa Pandacan si-nasabing sinulat niya ang kanyang Florante at Laura, ang mahigit na mahabang pana-hon sa buhay ni Balagtas ay dito naganap sa Udyong, sa Balanga at saka sa Udyong. Dito niya nakatagpo ang kanyang naging kabiyak na si Juana Tiambeng.” (We thought of this last year to give recognition to the fact that even though he was born in Bulacan, even though it is said that he wrote Florante at Laura in Pandacan, it was here in Udyong, in Balanga and Udyong, Balagtas lived a large part of his life. He met his wife Juana Tiambeng here.)

Almario expressed many big plans for the commemoration of Balagtas as well as in the efforts of promoting Philippine lit-erature in general. One is to make Araw ni Balagtas a national non-working holiday, and he hopes that by the third time they will celebrate Araw ni Balagtas it comes to frui-tion. A resolution has been sent to Malacan-an Palace. He was glad though that Bataan

had declared Araw ni Balagtas a provincial holiday.

He was much pleased that another dream was realized this year—the declara-tion of April as National Literature Month.

“Tinaon naming Abril dahil gusto naming magsimula ang pagdiriwang ng National Lit-erature Month sa Araw ni Balagtas. Simula sa araw na ito, ang pagdiriwang ng Araw ni Balagtas ay pambungad na ng National Literature Month,” (We timed it in April because we want to start the celebration of National Literature Month with Araw ni Balagtas. Beginning today, the celebration of Araw ni Balagtas is already the introduc-tion of National Literature Month) Almario explained.

Aside from Araw ni Balagtas, many liter-ature-related events fall under April such as the birth and death anniversaries of literary icons Emilio Jacinto, Paciano Rizal, Nick Joaquin, Edith Tiempo and Bienvenido Lumbera, and international literary cel-ebrations including International Children’s Book Day, International Day of the Book or World Book Day, and World Intellectual Property Rights Day. Also, during this sum-mer month, several writers’ workshops are being held.

The uses and roles of literature are multi-tudinous and multifarious. One universally accepted attribute of literature is its ability to provide elevating and edifying experienc-es which enlarge our horizons and enhance us as a people. In the Philippines, as in nu-merous countries in the world, literature also has a vital role in turning the course of history and shaping society. These liter-ary works are not necessarily revolutionary and patriotic, but also works even by sheer beauty and deepness of thought that came to define us as a people, as human.

According to poet and officer in charge

of the Sangay ng Edukasyon at Networking of KWF John Enrico Torralba: “Sa kasay-sayan, naging kasangkapan ang panitikan sa pagsulong at pagpapalaganap ng mga ad-hikain ng mga dakilang tao at karaniwang masa, lalo na ang dalumat ng pagkabansa. Mula noon hanggang kasalukuyan, ang pa-nitikan ang isa sa mga pangunahing sang-gunian ng pagkatao ng mga Filipino, ng pa-giging tao ng mga Filipino. Sumasalamin at naglalatag ang panitikan ng kung ano tayo at kung saan ang maaari nating kahantungan.” (In history, literature has been instrumen-tal in the flourishing and promulgation of the goals of great persons as well as of the ordinary masses, especially on the concept of nationhood. From the olden times until now, literature is one of the primary guides in shaping Filipino identity and humanity. Literature mirrors and illustrates what we are and where we are going.)

“Malawak at malayo na din ang naabot ng ating panitikan. May pagtanggap at pagkilala na sa iba’t ibang antas ang lipunan—mula sa mga internasyonal na larang hanggang sa mga karaniwang sulok ng mga tahanan, mula sa maseselang panlasa hanggang sa sim-pleng pagkalibang,” (Our literature has gone a long way. It has garnered reception and recognition in different levels of society—from the international field to the ordinary corners of the home, from critics with the most discerning tastes to the ones who just want diversion) he further explained. “Ang kapangyarihan at kabuluhang ito ng paniti-kan ng mga Filipino ang siyang dahilan, sa tingin ko, kung bakit may Buwan ng Paniti-kang Filipino. Dagdag pa, may sakit na pag-kalito at pagkalimot ang maraming Filipino kung kaya’t kailangang ipaalam at ipaalala sa kanila ang kapangyarihan at kabuluhang ito, na tayo ay may panitikan, na tayo ay Fili-pinong may maipagmamalaking panitikan.”

2015 • Number 2 • Agung 7

(The power and significance of Philippine literature are reasons, in my opinion, why there is a Philippine Literature Month. Ad-ditionally, many Filipinos are afflicted with confusion and forgetfulness, and there is need to remind them of literature’s power and significance, that we have a literature we can be proud of.)

Now, the whole nation can highlight the importance of literature every year. Presi-dent Benigno Aquino III signed Proclama-tion No. 968 on February 10, 2015, which declares the month of April as Buwan ng Panitikang Filipino or National Literature Month.

The proclamation states that “Philippine literature, written in different Philippine languages, is associated with the history and cultural legacy of the State, and must be promoted among Filipinos,” and that “national literature plays an important role in preserving and inspiring the literature of today and in introducing to future genera-tions the Filipino values that we have inher-ited from our ancestors.”

Right after the establishment of Na-tional Literature Month, the government agency on the national language and other

sa pamamagitan ng tuloy-tuloy na produksi-yon at promosyon.” (Another objective is to encourage Filipinos, the professionals, the non-professionals, students, teachers and others to take part in sustaining, popular-izing and disseminating Filipino creativity through continuous production and pro-motion.)

He concluded: “Ay lab panitikan. Sa ka-buuan, ang nais na maabot ng selebrasyon ay mas malalim na pagpapahalaga sa ating pa-nitikan, at higit sa lahat, ipakita na mahal natin ang ating panitikan.” (I love literature. Overall, the celebration hopes to foment a deeper appreciation for our literature and to show that we love our literature.)

The line-up of activities and events con-sisted of established regular endeavors as well as new ones. Even though the preparation for the celebration was rushed, KWF was able to draw a calendar of activities. Foremost were the monument unveiling and the Kampo Balagtas from March 30 to 31, which gath-ered around 500 Grade 8 students in the Central Luzon region and delegations from different indigenous groups of the country. With the theme “Si Balagtas at ang Kabata-an” (Balagtas and the youth), the camp gave

Philippine languages, with support from the NCCA, the government’s overall agency on arts and culture, rushed through its first-ever celebration.

First, KWF chose the theme “Alab Pani-tikan,” literally “fire of literature,” which is also a play on the phrase “I love panitikan.” The theme also encapsulated the goals of the celebration this year.

“Nag-aalab ang panitikang Filipino,” (Philippine literature is burning) Torralba said. “Isang layunin ng pagdiriwang ay ipaa-lala na may mahabang kasaysayan, kung kaya’t may malalim at malawak na lawas ng mga akda ang Filipinas; at ipakilala na patuloy na nabubuhay ang ating panitikan.” (One objective of the celebration is to re-mind people of the long history of Philip-pine literature—thus, it has a deep and wide body of works— and that it continues to be alive.)

“Pag-alabin ang panitikang Filipino,” (To kindle Philippine literature further) he con-tinued. “Isa pang layunin ay hikayatin ang mga Filipino, mga propesyonal , di-propesyo-nal, mag-aaral, guro, at iba pa na makibahagi sa pagpapanatili, pagpapalaganap, at pagpa-palawak ng pagkamalikhain ng mga Filipino

A new monument of Francisco “Balagtas” Baltazar was unveiled on March 30, 2015, in Orion, Bataan, led by NCCA chairman Felipe de Leon, Jr.; National Artist for literature and chairman of the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino Virgilio Almario; Antonio Raymundo, Jr., mayor of Orion; and Albert S. Garcia, Bataan governor, among others.

8 Agung • Number 2 • 2015

Francsico “Balagtas” Baltazar is widely considered as the Prince of Tagalog Poets because of his masterpiece, the metrical romance Florante at Laura. He is also considered to have changed the course of literature during the Spanish colonial period. He was admired by both Jose Rizal and Andres Bonifacio for the outstanding craftsmanship of Florante at Laura. Balagtas’ revolutionary political and social ideas were admired also by them as well as by poets of today.

It is very unfortunate that many of Balagtas’ awit and komedya were destroyed when his home in Bataan burned down, save for one saynete, La india elegante y el negrito amante. The manuscript of the komedya Orosman at Zafira was recently discovered, attesting to his immense talent as poet-playwright and showing his advanced political leanings.

Balagtas was born on April 2, 1788, in Panginay, Bigaa (now Balagtas), Bulacan, to Juan Balagtas and Juana Cruz. He was sent to relatives in Tondo, Manila, to serve as house help in exchange for education. He attended Colegio de San Jose and Colegio de San Juan de Letran. In Colegio de San Jose, he was listed as “Francisco Baltazar.” This is also the name used in the marriage document when he married Juana Tiambeng in July 22, 1842. There is no clear explanation on the change of surname.

In 1835, he fell in love with Maria Asuncion Rivera of a wealthy clan in Pandacan, but the affair did not prosper. “Kay Celia,” the introductory poem of Florante at Laura, was dedicated to her. In Pandacan, Balagtas was incarcerated, the reason of which is still unknown. He was freed on 1838, the year Florante at Laura is said to have been published. Balagtas moved to Udyong (now Orion) in Bataan, where he married Juana Tiambeng and raised eleven children. He was again imprisoned in 1856, following a complaint by a house help whose hair was cut off by Balagtas for unknown reason. The case impoverished the Balagtas family. He was imprisoned in Balanga, Bataan, and was transferred to Tondo, where he wrote many komedyas for Teatro de Tondo from 1857 to 1860. After the imprisonment, he went back Udyong, where he wrote many poems and komedyas until his death in February 20, 1862.

lessons on first aid and martial arts, among other things, and featured cultural presenta-tions and discussions on the importance of Balagtas’s life and legacy. During its open-ing, the winners of Talaang Ginto: Makata ng Taon and Gawad Dangal ni Balagtas were declared. Freelance writer Christian Ray Pilares was honored as Makata ng Taon in the poetry contest in Filipino for his poem “Pingkian,” while Michael Jude Cagumbay Tumamac placed second for “Pananaginip kay Tud Bulul” and Francisco Arias Monte-sena third for “Bahagdan, Walang Sukat ang Bayaning Kabataan.” Rogelio Mangahas, known as part of a triumvirate that ushered in the second movement in Modernism in poetry in Filipino, was given the lifetime achievement award.

Literary events for the rest of the month included Tertulya sa Tula: Isang Hapon ng mga Makata ng Taon every Monday at the KWF headquarters, where audiences had the opportunity to interact with the Makata ng Taon winners. Meanwhile, the Filipino poets’ group Linangan sa Imahen, Retorika, at Anyo (LIRA) conducted the Lakbay-Pa-nitik para kay Emilio Jacinto in Majayjay, Laguna, in celebration of the hero’s death anniversary. On the other hand, Gumil Fili-pinas (Gunglo dagiti Mannurat nga Ilokano iti Filipinas) or Ilokano Writers Association of the Philippines held its 47th national conference at the Cubao Expo in Quezon City with the theme “Ang Papel ng Gumilia-no sa Lipunang Ilokano.” (The role of a Gu-mil member in Ilocano society). LIRA also had a poetry reading program at the Con-spiracy Bar in Quezon City, while in Davao City, the Davao Writers’ Guild and Young Davao Writers held Kumbira! which includ-ed a poetry reading, an exhibit and a book sale. A poetry reading by the Katig Writers Network was mounted at University of the Philippines Tacloban in Leyte and at the Northwestern State University in Calbayog City, Samar. A Cebuano version of the play The Vagina Monologues by Eve Ensler, called V-Latanay, was staged at the University of the Philippines in Mindanao.

Some of the activities were educational such as “Tradisyon at Modernidad: Isang Simposyum” of the University of Santo Tomas’s Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies, and a translation seminar for teachers at the Western Mindanao State University in Zamboanga City. The Old Tagalog abugida or baybayin was the focus of a summit in Lingayen, Pangasinan, from April 9 to 11, participated in by teachers, scholars, researchers and students, tackling the issue of introducing the abugida into the school curriculum. On the other hand, the Ortograpiyang Pambansa, KWF Manwal sa

FRANCISCO “BALAGTAS” BALTAZAR

Masinop na Pagsulat, and Korespondensiya Opisyal was tackled at the Uswag Filipino!, an annual seminar-workshop on language and literature for teachers, at the Bulacan State University. The Klasrum Adarna ses-sion for teachers tackled “Pagtuturo ng Noli at Fili/Ibong Adarna” in Makati City while the “Folk on Badiw: Ibaloy Legacy to Poetry and Music” was held at the University of the Philippines in Baguio City with National Artist for music Ramon Santos as guest of honor. Also in Baguio City, the Kapisanan ng mga Superbisor at Guro sa Filipino (Ka-sugufil) mounted the Pambansang Kongreso sa Wikang Filipino.

The Pambansang Araw ng Gawad sa KWF Timpalak Uswag Darepdep , a contest of the KWF for 12 to 17-year-old aspiring writ-ers writing in different Philippine languages was opened. This year, language categories open for competition are Ilocano, Cebuano, Bicol and Mëranaw.

The month also abounded in writing workshops. Ateneo de Manila Univer-sity’s Ateneo Institute of Literary Arts and Practices held the High Fantasy and Young Adult Writing Workshop every Saturday of the month while the Bienvenido Santos Creative Writing Center of the De La Salle University held the Young Writers Work-shop for very young children with literary inclinations. The Manila Times College in Intramuros, Manila conducted a literary journalism workshop with veterans that included critic and playwright Dr. Isagani Cruz. From April 26 to 28, the Iyas Nation-al Writers Workshop of the University of St. La Salle-Bacolod was held in Bacolod City, Negros Occidental.

On April 23, the National Book Devel-opment Board spearheaded the celebration of the National Book and Copyright Day.

The Holy Week is not the only occa-sion that provides spirituality, reflection and meaningfulness during this season popu-larly known for excursions and beaches. With the newly declared Buwan ng Paniti-kang Filipino or National Literature Month, April in the Philippines will be a more en-riching and soulful time.

“Mas malalaki at bonggang uri ng mga gawain,” (Bigger and spectacular activities) promised Torralba on future celebrations. “Noong huling meeting sa NCCA, nakaiisip na ng ilang malalaking gawain para sa susu-nod na taong pagdiriwang. Nariyan ang mga pagkakaroon ng mga pambansang timpalak sa mga tradisyonal na anyo ng panitikan ng bansa gaya ng timpalak sa balagtasan, tigsik, ambahan, balitao, etc. Isa ding mungkahi ay ang pagkakaroon ng Gawad Alab Panitikan. Siyempre, ninanais na buong bansa o karami-han ng mga sektor, institusyon, o organ-

The Komisyón sa Wikàng Filipíno (KWF) or the National Language Commission, established by virtue of Republic Act. 7104, signed on August 14, 1991, is the government agency tasked in conducting researches, developing, propagating and promoting the Filipino language and other Philippine languages. An important goal is to develop the Filipino language for national development and unity and at the same time to preserve and propagate other indigenous and regional languages. It is the mission of the KWF to formulate, coordinate and implement research programs and projects to further the development and enrichment of Filipino as a medium of general communication as well as for intellectual pursuits. Visit www.kwf.gov.ph, or e-mail [email protected]. Call telephone number 736-2519 for more information.

THE KOMISYÓN SA WIKÀNG FILIPÍNO

ORION, BATAANisasyong may direkta o di-direktang may kinalaman sa panitikan ay magiging ba-hagi ng mga susunod pang pagdiriwang. Sa madaling salita, asahang paganda nang paganda at palaki nang palaki ang mga pagdiriwang sa hinaharap. Ano pa ba ang maaasahan natin sa mga taong puro paglikha ang nasa isip at puso?” (In the last meeting at the NCCA, several big events were suggested for the sub-sequent celebrations. One is a national contest on traditional literary forms such as the balagtasan, tigsik, ambahan, balitao, etc. Another suggestion is hav-ing an Alab Panitikan Award. Of course, it is hoped that the whole country or most of the sectors, institutions or orga-nizations directly or indirectly connect-ed with literature will take part in the coming celebrations. In other words, expect that the future celebrations will be bigger and more beautiful. What can we expect from people whose hearts and minds are into creating?”)

As the sun shines bright that season, so will the immortal words come alive and become dazzling, illuminating the path for and make luminous the na-tion’s soul.

Orion in Bataan, 132 kilometers from Manila, was formerly called Udyong. Records show that the municipality was founded by a Dominican priest on April 30, 1667, but this cannot be ascertained.

There is a folklore on how the town got its name. Udyong is said to be derived from lu-ad and uryong, meaning “muddy.” Some Spanish soldiers, another story goes, passed by the town and asked for the name of the place, pointing to the ground. The locals, not understanding their query and seeing a worm on the ground, said “Uod ‘yon.” Udyong later became Orion, a mispronunciation.

The most important heritage structure of the town is the Parish Church of Saint Michael the Archangel. The present structure was built by Father Jose Campomanes, O.P. after an earthquake in 1852 destroyed a previous structure. Its façade is described as of barn-style Baroque, featuring side pillars capped by urn-like finials, pilasters that divide the façade into five segments and cornices that divide the expanse of the wall into two levels. The pediment is semi-arched and ends into two small volutes before tapering down to the sides. A concrete porte cochere has been added later into the structure. There is a four-level belfry.

Orion is proud of producing Don Cayetano Arellano, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, who was born here on March 2, 1847.

The Saint Michael the Archangel Church (top), Manila Bay from the shore of Wawa (above) and the town proper of Orion (below)

10 Agung • Number 2 • 2015

VIRGILIO S. ALMARIO (born March 9, 1944), also known for his penname Rio Alma, is a poet, literary historian and critic as well as a professor, translator, editor, lexicographer and cultural administrator. He revived and

reinvented traditional Filipino poetic forms, even as he champi-oned modernist po-etics. His first book of poetry, Makinasyon at Ilang Tula, was pub-lished in 1967, and it was followed by many more, including Peregrinasyon, the tril-ogy Doktrinang Anak-

pawis, Mga Retrato at Rekwerdo and Muli, Sa Kandungan ng Lupa. His poetry was col-lected in two volumes, Una Kong Milenyum. In these works, his poetic voice soared from the lyrical to the satirical to the epic, from the dramatic to the incantatory, in his often se-vere examination of the self, and the society. He has also redefined how Filipino poetry is viewed and paved the way for the discussion of the same in his books of criticisms and an-thologies. He founded the Galian sa Arte at Tula and the Linangan sa Imahen, Retorika at Anyo, which nurtured and mentored many writers. He has also long been involved with children’s literature. He has been a constant presence as well in national writing work-shops and galvanizes member writers as chairman emeritus of the Unyon ng mga Manunulat sa Pilipinas. He headed the NCCA as executive director from 1998 to 2001, and is currently KWF chairman. He was declared National Artist in 2003.

FRANCISCO ARCELLANA (September 6, 1916-August 1, 2002), fictionist, poet, es-sayist, critic, journalist and teacher, was one

of the most impor-tant progenitors of the modern Filipino short story in English. He pioneered the development of the short story as a lyrical prose-poetic form. Ar-cellana kept alive the experimental tradi-tion in fiction and was

Our Writers, Our National Artists

most daring in exploring new literary forms to express the sensibility of the Filipino peo-ple. His books include Selected Stories (1962), Poetry and Politics: The State of Original Writ-ing in English in the Philippines Today (1977) and The Francisco Arcellana Sampler (1990). He was declared National Artist in 1990.

CIRILO F. BAUTISTA (born July 9, 1941) is a poet, fictionist and essayist. Throughout his career that spans more than four decades, he has established a reputation for fine and profound artistry. His books, lectures, poetry

readings and creative writing workshops continue to influence his peers and genera-tions of young writers. In De La Salle Universi-ty, he was instrumen-tal in the formation of the Bienvenido Santos Creative Writing Cen-ter. He was also the moving spirit behind

the founding of the Philippine Literary Arts Council in 1981, the Iligan National Writers Workshop in 1993, and the Baguio Writers Group. Bautista continues to contribute to the development of Philippine literature: as a writer, through his significant body of works; as a teacher, through his discovery and en-couragement of young writers in workshops and lectures; and as a critic, through his essays that provide insights into the craft of writing and correctives to misconceptions about art. His major works include the poetry Summer Suns (1963), Words and Battlefields (1998), The Trilogy of Saint Lazarus (2001) and Galaw ng Asoge (2003). He was declared National Artist in 2014.

LAZARO FRANCISCO (February 22, 1898–June 17, 1980) developed the so-cial realist tradition in Philippine fiction. His eleven novels, now ac-knowledged classics of Philippine literature, embody the author’s commitment to na-tionalism. Francisco gained prominence as

a writer not only for his social conscience but also for his “masterful handling of the Tagalog language” and “supple prose style.” With his literary output in Tagalog, he con-tributed to the enrichment of the Filipino language and literature for which he is a staunch advocate. He put up an arm to his advocacy of Tagalog as a national language by establishing the Kapatiran ng mga Al-agad ng Wikang Pilipino (Kawika) in 1958. He is widely considered the “Master of the Tagalog Novel” and his novels include Ama, Bayang Nagpatiwakal, Maganda Pa Ang Daigdig and Daluyong. He was declared National Artist in 2009.

N. V. M. GONZALES (September 8, 1915–November 28, 1999), whose N.V.M. stands for Nestor Vicente Ma-dali, was a fictionist, essayist, poet and teacher known for appropriating the English language to express, reflect and shape Philip-pine culture and Philippine sensibility. He became University of the Philippines’ International Writer-in-Residence and a member of the Board of Advisers of the UP Creative Writing Center. In 1987, U.P. conferred on him the Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa, its highest academic recognition. Major works include The Winds of April, Seven Hills Away, Children of the Ash-Covered Loam and Other Stories, The Bamboo Dancers, Look Stranger, on this Island Now, Mindoro and Beyond: Twenty -One Stories, The Bread of Salt and Other Stories, Work on the Mountain, The Novel of Justice: Selected Essays 1968-1994, and A Grammar of Dreams and Other Stories. He was declared National Artist in 1997.

WILFRIDO MA. GUERRERO (Janu-ary 22, 1911 - April 28, 1995) was a teacher and theater artist whose 35 years of devot-ed professorship had produced the most sterling luminaries in Philippine perform-ing arts today. In 1947, he was appointed as UP Dramatic Club director and served for 16 years. As founder and artistic direc-

2015 • Number 2 • Agung 11

tor of the UP Mobile Theater, he pioneered the concept of the-ater campus tour and delivered no less than 2,500 performances in a span of 19 commit-ted years of service. By bringing theatre to countryside, Guerrero made it possible for

students and audiences in general to experi-ence the basic grammar of staging and act-ing in familiar and friendly ways through his plays that humorously reflect the behavior of the Filipino. His plays include Half an Hour in a Convent, Wanted: A Chaperon, Forever, Con-demned, Perhaps, In Unity, Deep in My Heart, Three Rats, Our Strange Ways, The Forsaken House, and Frustrations. He was declared Na-tional Artist in 1997.

NICK JOAQUIN (May 4, 1917-April 29, 2004) is regarded by many as the most distin-guished Filipino writer in English, writing so variedly and so well about so many aspects of the Filipino. Joaquin has also enriched the English language with critics coining “Joaquinesque” to describe his baroque S p a n i s h - f l a v o r e d English or his reinven-tions of English based on Filipinisms. Aside from his handling of language, Bienvenido Lumbera writes that Nick Joaquin’s signifi-cance in Philippine literature involves his ex-ploration of the Philippine colonial past un-der Spain and his probing into the psychol-ogy of social changes as seen by the young, exemplified in stories such as “Doña Jeroni-ma,” “Candido’s Apocalypse” and “The Order of Melchizedek.” He has written plays, novels, poetry, short stories and essays including reportage and journalism. As a journalist, he used the nome de guerre Quijano de Manila. Among his works are The Woman Who Had Two Navels, A Portrait of the Artist as Filipino, Manila, My Manila: A History for the Young, The Ballad of the Five Battles, Rizal in Saga, Alma-nac for Manileños, and Cave and Shadows. He was declared National Artist in 1976.

F. SIONIL JOSE (born December 3, 1924) is well-known as a novelist, the most published outside the country. His writings since the late 1960s, when taken collectively, can best be de-scribed as epic. Its sheer volume puts him on the forefront of Philippine writing in English. But ultimately, it is the consistent espousal of the aspirations of the Filipino—for national sovereignty and social justice—that guaran-

tees the value of his oeuvre. In the five-novel masterpiece, the Rosales saga, con-sisting of The Pretend-ers, Tree, My Brother, My Executioner, Mass, and Po-on, is a sweeping work that captures Philippine history while simulta-

neously narrating the lives of generations of the Samsons whose personal lives intertwine with the social struggles of the nation. He was declared National Artist in 2001.

AMADO V. HERNANDEZ (September 13, 1903–March 24, 1970) was a poet, play-wright and novelist, who practiced “com-mitted art.” In his view, the function of the writer is to act as the conscience of society and to affirm the greatness of the human spirit in the face of inequity and oppression. Hernan-dez’s contribution to the development of Tagalog prose is considerable. He stripped Tagalog of its ornate character and wrote in prose closer to the colloquial than the “official” style permitted. His novel Mga Ibong Manda-ragit, first written while in prison, is the first Filipino socio-political novel that exposes the ills of the society as evident in the agrarian problems of the 1950s. Other works include Bayang Malaya, Isang Dipang Langit, Luha ng Buwaya, Amado V. Hernandez: Tudla at Tudling: Katipunan ng mga Nalathalang Tula 1921-1970, Langaw sa Isang Basong Gatas at Iba Pang Kuwento ni Amado V. Hernandez, and Magkabilang Mukha ng Isang Bagol at Iba Pang Akda ni Amado V. Hernandez. He was declared National Artist in 1973.

BIENVENIDO LUMBERA (born April 11, 1932), poet, professor, librettist and schol-ar, introduced to Tagalog literature what is now known as Bagay poetry, a landmark aes-thetic tendency that has helped to change the vernacular poetic tradition. His works include Likhang Dila, Likhang Diwa (poetry in Filipino and Eng-lish, 1993); Balaybay: Mga Tulang Lunot at Manibalang (2002); Sa Sariling Bayan: Apat na Dulang may Musika (2004); and Agunyas sa Hacienda Luisita, Pakikiramay

(2004). He wrote the libretto for The Tales of the Manuvu and Rama Hari, pioneering the creative fusion of fine arts and popular imag-ination. As a scholar, his major books include Tagalog Poetry, 1570-1898: Tradition and Influ-ences in its Development; Philippine Literature: A History and Anthology; and Revaluation: Essays on Philippine Literature, Writing the Na-tion/Pag-akda ng Bansa. He was declared Na-tional Artist in 2006.

SEVERINO MONTANO (1915-Decem-ber 12, 1980) was a playwright, director, actor and theater organizer. He is the forerunner in institutionalizing “legitimate theater” in the Philippines. Taking up courses and gradu-ate degrees abroad, he honed and shared his expertise with his countrymen. As dean of instruction of the Philippine Normal College, Montano organized the Arena Theater to bring dra-ma to the masses. He trained and directed the new generations of dramatists including Rolando S. Tinio, Em-manuel Borlaza, Joonee Gamboa, and Behn Cervantes. He established a graduate pro-gram at the Philippine Normal College for the training of playwrights, directors, tech-nicians, actors and designers. He also estab-lished the Arena Theater Playwriting Contest that led to the discovery of Wilfrido Nolledo, Jesus T. Peralta and Estrella Alfon. He was de-clared National Artist in 2001.

CARLOS P. ROMULO (January 14, 1898–December 15, 1985) is well known for a career that spanned about 50 years in public service as educator, soldier, university president, jour-nalist and diplomat. It is commonly regard-ed that he is the first Asian president of the United Nations Gen-eral Assembly, then Philippine ambassador to Washington, D.C., and later minister of foreign affairs. He was a reporter at the age of sixteen, a newspa-per editor by the age of 20, and a publisher at 32. He was the only Asian to win the United States’ prestigious Pulitzer Prize in journalism for a series of articles predicting the outbreak of World War II. Romulo wrote and published 18 books, including The United (novel), I Walked with Heroes (autobiography), I Saw the Fall of the Philippines, Mother America, and I See the Philip-pines Rise (war-time memoirs). He was declared National Artist in 1982.

12 Agung • Number 2 • 2015

ALEJANDRO R. ROCES (July 13, 1924-May 23, 2011) was a short story writer and essayist, considered as the country’s best writer of comic short stories. He is known for his widely anthologized “My Brother’s Pecu-liar Chicken.” In his innumerable newspaper columns, he had always focused on the ne-

glected aspects of the Filipino cultural heri-tage. His works have been published in various international magazines and has received national and international awards. Roces brought to public attention the aesthetics of the country’s fiestas. He

was instrumental in popularizing several local fiestas, notably, the Moriones and the Ati-atihan. He personally led the campaign to change the country’s Independence Day from July 4 to June 12; caused the change of language from English to Filipino in the country’s stamps, currency and passports; and recovered Jose Rizal’s manuscripts when they were stolen from the National Archives. He was declared National Artist in 2003.

EDITH L. TIEMPO (April 22, 1919- Au-gust 21, 2011) was a poet, fictionist, teacher and literary critic, one of the finest Filipino writ-ers in English whose works are characterized by a remarkable fusion of style and substance, of craftsmanship and insight. Her poems are intricate verbal transfigurations of significant experiences. As fic-tionist, Tiempo is as morally profound. Her language has been described as “descrip-tive but unburdened by scrupulous detail-ing.” She is an influen-tial figure in Philippine literature in English. Together with her late husband, Edilberto K. Tiempo, she founded and directed the Sil-liman National Writers Workshop in Duma-guete City, which has produced some of the country’s best writers. Her works include the novel A Blade of Fern (1978), The Native Coast (1979), and The Alien Corn (1992); the poetry collections The Tracks of Babylon and Other Po-ems (1966), and The Charmer’s Box and Other Poems (1993); and the short story collection Abide, Joshua, and Other Stories (1964). She was declared National Artist in 1999.

ROLANDO S. TINIO (March 5, 1937-July 7, 1997) was a playwright, thespian, poet, teacher, critic and translator, with a ca-reer marked by prolific artistic productions.

Tinio’s chief distinction is as a stage director whose original insights into the scripts he handled brought forth productions notable for their visual impact and intellectual co-gency. Subsequently, after staging produc-tions for the Ateneo Experimental Theater (its organizer and ad-ministrator as well), he took on Teatro Pilipino. It was to Teatro Pilipino which he left a consider-able amount of work reviving traditional Filipino drama by re-staging old theater forms like the sar-swela and opening a treasure house of contemporary Western drama. It was the excellence and beauty of his practice that claimed for theater a place among the arts in the Philippines in the 1960s. Aside from his collections of poetry (Sitsit sa Kuliglig, Dunung-Dunungan, Kristal na Uniberso, A Trick of Mirrors) among his works were the screenplays Now and Forever, Gamitin Mo Ako, Bayad Puri and Milagros; sarswelas Ang Mestisa, Ako, Ang Kiri, Ana Maria; and Lar-awan, the musical. He was declared Nation-al Artist in 1997.

JOSE GARCIA VILLA (August 5, 1908-February 7, 1997) is considered as one of the finest contemporary poets regardless of race or language. He introduced the re-versed consonance rime scheme, including the comma poems that made full use of the punctuation mark in an innovative, poetic way. The first of his poems, “Have Come, Am Here,” received critical recognition when it appeared in New York in 1942. He used Doveglion (dove, eagle, lion) as pen-name, the very char-acters he attributed to himself, and the same ones explored by e.e. cummings in the poem he wrote for Villa (“Doveglion, Adventures in Value”). Villa’s works have been collected in Footnote to Youth, Many Voices, Poems by Doveglion, Poems 55, Poems in Praise of Love: The Best Love Poems of Jose Garcia Villa as Chosen By Himself, Selected Stories, The Portable Villa, The Essential Villa, Mir-i-nisa, Storymasters 3: Selected Stories from Footnote to Youth, 55 Poems: Selected and Translated into Tagalog by Hilario S. Francia. He was declared Na-tional Artist in 1973.

Reference: NCCA Web site (www.ncca.gov.ph)

Manlilikha ng Bayan Ginaw Bilog was a Hanunoo Mangyan poet who vigorously promoted the elegant poetic art of the surat Mangyan and the ambahan. He kept scores of ambahan poetry recorded for posterity.

A common cultural aspect among cultur-al communities nationwide is the oral tradition characterized by poetic verses which are either sung or chanted. However, what distinguishes the rich Mangyan literary tradition from others is the ambahan, a poetic literary form com-posed of seven-syllable lines used to convey messages through metaphors and images. The ambahan is sung and its messages range from courtship, giving advice to the young, asking for a place to stay, saying goodbye to a dear friend and so on. Such an oral tradition is com-monplace among indigenous cultural groups but the ambahan has remained in existence today chiefly because it is etched on bamboo tubes using ancient Southeast Asian, pre-colo-nial script called surat Mangyan.

Ginaw Bilog from Kalaya, Bait, Mansalay, Oriental Mindoro, grew up in such a cultural en-vironment. Already steeped in the wisdom that the ambahan is a key to the understanding of the Mangyan soul, Ginaw took it upon himself to continually keep scores of ambahan poetry recorded, not only on bamboo tubes but on old notebooks passed on to him by friends.

Most treasured of his collection are those inherited from his father and grandfa-ther, sources of inspiration and guidance for his creative endeavors. Through the dedica-tion of Ginaw, the ambahan poetry and oth-er traditional art forms from our indigenous peoples will continue to live.

Ginaw Bilog was conferred the Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan in 1993. He passed away in 2003.

GINAW BILOG

2015 • Number 2 • Agung 13

The audience, especially the young wom-en, were cheering almost wildly while watch-ing a handsome young man from Finland named Signmark singing, using his body—his hands and fingers, his facial expressions, his thumping feet, his gyrating hips. It was be-cause he is deaf but is most eager to share his musical talent during the opening program of the Association of Southeast Asian Na-tions (ASEAN) Literary Festival on March 19, 2015, at the Teater Kecil, Taman Ismail Mar-zuki, in Central Jarkarta, Indonesia.

Fifty-nine writers, publishers and lit-erary critics from all over the world par-ticipated at festival held from March 15 to 22, 2015, with the theme, “Questions of Conscience.” Founding festival director Ab-dul Khalik said the main objective of this festival, now on its second year, is “to cre-ate a platform where writers and scholars from the member countries of the Associa-tion of Southeast Asian Nations can get to know each other and exchange ideas on how they can contribute to the solution of the problems of society” and to “help build the ASEAN community.”

Questions and Conscience at the ASEAN Literary Festival 2015

By John Iremil E. Teodoro

Indonesian Foreign Affairs Minister Retno Marsudi graced the opening night and wished everyone to “spread understand-ing through literature.” The general lecture that evening was delivered by Ma Thida, a Burmese surgeon, writer and human rights activist. In 1993, she was sentenced to 20 years in prison for supporting the pro-democracy movement in the then military controlled Myanmar. Her lecture was en-titled “How Literature Helps Building Free-dom and Democracy in ASEAN” in which she underscored the role of literature in the Asean community.

“Literature also helps readers to do self-analysis of their beliefs and perspectives on everyday life. Reading about different cul-tures and societies through the writer’s per-spective is indeed generating the capacity of readers on tolerance and respect on other viewpoints,” she said.

The Philippine delegation was com-posed of National Artist for literature Vir-gilio Almario, Bicol poet Kristian Sendon Cordero, and myself, a Kinaray-a writer. The National Commission for Culture and the

Arts gave us travel grants and the Philippine Embassy in Indonesia along with the festival organizers took good care of us. The fourth Filipino delegate and member of the steering board of the festival was Jamil Maidan Flores, a journalist whose byline is familiar in the Philippines in the 1980s and 1970s but for several years now is based in Jakarta, writing speeches for Indonesia’s foreign ministers. He is also a respected columnist in the Jakarta Globe, a daily English-language paper.

The literary festival features many work-shops, performances and discussions, all free and open to the public. In the panel discus-sion “Locality in Asean Literature,” Singa-porean novelist Josephine Chia said, “I don’t think a writer can write in a vacuum. You have to write from a society.” Australian writer Mi-chelle Aung Thin agreed with her and said, “Stories come from a place, from a certain time.” Indonesian literary critic Manneke Budiman problematized the term “locality.” He would like to think of “locality as intersec-tions,” and there should be “engagements to create a locality” among writers and readers. He was also quick to add that he doesn’t like

The panel discussion, “Literatures in Digital Era”, with the author (third from left)

14 Agung • Number 2 • 2015

the term “ASEAN literature” because this is homogenizing and that “lo-calities” should always be on the plural form.

It is also in this panel that U Kang, a Myanmarese writer who had so far authored 96 books, mentioned that the two novels of Jose Rizal are being read in their country. Of course, in the Burmese translation. At the festival, I also learned that Rizal’s works and life are being read in translations in Indonesia and Vietnam. In fact, one of the Indonesian delegates, a playwright and actor, is named Jose Rizal Manua. It was a shame we were not able to meet him.

The panel discussion, where I read a paper, was entitled “Litera-tures in Digital Era.” Saut Situmorang, a cult literary figure in Indo-nesia today, talked about the Web site of e-books he founded called Multi-media Literature Foundation, especially about how the main-stream and “elitist” newspapers in Jakarta branded their publications as “crap literature.” But he was happy to share that today their Web site has already many followers and their publications have many subscribers thus becoming “mainstream.” Saut laughed and danced a little when I told him that in Kinaray-a his name is “dance.”

Japanese book coordinator and bookshop owner Shintaro Un-chinuma noted that since 1997 book sale in Japan has declined. He also said that 10 percent of the sales are e-books. Because of this trend, he averred that bookstores are not only a place now to buy books but also a happy space where writers, readers and artists would meet. His bookstore in Tokyo, called B&B, is a place where people can drink beer and enjoy literary events such as poetry readings everyday.

For my part, I presented statistics on the Internet users in the Philippines. In 2014, 39.4 million or 39 percent of Filipinos use the Internet but there is a study saying that majority of these users only use social media such as Facebook and Twitter and has little to do with reading e-books. The Philippine population today is 106.4 million and those who have access to electricity is 83.3 percent. That is roughly 18 million Filipinos living in the dark literally. So, can we even talk about the aesthetics of e-publishing when many of our marginalized and poor Southeast Asian sisters and brothers do not have access to Internet for the simple reason that they don’t even have electricity in their homes?

Cordero spoke in the panel discussion entitled “Radicalism and Moderation in Literature.” He shared to an international audience the history of literatures in the Philippines which have “always been revolutionary, if not critical.” Being a Bicolano, he also highlighted the language issue and added that our literature “is peopled with ethno-linguistic groups who have kept their literary traditions alive and relevant among its own people even up to these days despite the relentless pursuits of the colonizers. It is a living culture that refuses fossilization. Philippine literary writing has a pantheon of writers and intellectuals who through years of colonization after coloniza-tion have questioned and raised arms against the status quo or the prevailing order of their time.”

Almario, in the panel discussion “Consumerism vs. Literary Works,” said this: “Imagination is available to both the rich and the poor, the capitalist and the slave, the Westerner and the ASEAN, and can be freely used in any circumstance by anybody who works for it. Imagination is present in solitary tower and in the marketplace. The writer chooses what to make of it. Or rather, the motive does not de-termine the work. Imagination makes even a commercialized prod-uct greater than any work by a serious but unimaginative writer.”

The happy intersections between conscience and imagination will quicken us to create diverse and beautiful literatures that will make us—writers and readers—more human. This is what I learned from the ASEAN Literary Festival 2015.

Commemorative Stamp for the Birth Centenary of National Artist Severino Montano

The NCCA and the Philippine Postal Corporation (PhilPost) launched a commemorative stamp for the 100th birth anniversary of National Artist for theatre Severino Montano at the Leandro Locsin Auditorium of the NCCA, Intramuros, Manila, on March 12, 2015.

Assistant Postmaster General Luis Carlos along with Felipe M. de Leon, Jr., NCCA chairman, presented the commemorative stamps to Pedro Montano Ruenduen, Jr., nephew of Dr. Montano, who represented the family of the late National Artist.

“Severino Montano executed a large-scale feat for the small people of society and the afterglow of his works continues to light the path of the new generation of artists, poets, and playwrights,” noted De Leon.

Montano was a celebrated thespian and playwright during the 1950s. His works include Sabina, But Not My Sons Any Longer, Ga-briela Silang, Parting at Calamba, Speak, My Gentle Children, Lonely is My Garden, My Morning Star and The Love of Leonor Rivera, con-sidered the longest-running play, staged in more than a thousand times under the auspices of the Arena Theatre.

Montano, a Master of Fine Arts graduate of Yale University, is credited for professionalizing the theater industry in the Philippines with Arena Theater, which he funded with his own money and es-tablished while dean at the Philippine Normal College.

Montano’s pioneering of the Arena Theatre has been one of the many changes in the Filipino arts scene in the 50s. It has brought theatre arts as a form of entertainment and celebration of Filipino drama to the far flung barrios of the Philippines. Arena Theatre ca-tered to grassroots audience, bringing theatre closer to the hearts of the Filipino masses of his generation.

Before he died in 1980, he was mentor to theater luminaries such as Rolando S. Tinio, Emmanuel Borlaza, Joonee Gamboa, and Behn Cervantes. He was declared as National Artist for theatre in 2001.

The Montano stamp is classified as a “commemorative” kind of issue with a denomination of P10.00 and about 65,000 pieces were printed by Amstar Company, Inc. The stamp measures 40 by 30 millimteres and was laid out by PhilPost in-house artist, Victorino Serevo and Ryan Arengo of the NCCA Secretariat. The stamps are available at the Post Shop, Philately and Museum Division, Main Central Post Office, Door 203, Liwasang Bonifacio Manila. For in-quiries, call 527-0108.

2015 • Number 2 • Agung 15

A New Chapter for a Heritage StructureNCCA Acquires Metropolitan Theater in Manila

Designed by Juan Arellano, the Manila Metropolitan Theater stands as one of the finest example of Art Deco architecture and a recognizable landmark in the Lawton area. /Photo by Oliver Rosales

16 Agung • Number 2 • 2015

A New Chapter for a Heritage StructureNCCA Acquires Metropolitan Theater in Manila By Roel Hoang Manipon

The Manila Metropolitan Theater (Met) is now owned by the NCCA. The national government’s agency

in charge of arts and culture acquired the prominent heritage landmark in Manila for the sum of P270 million from the owner, the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS). The Deed of Absolute Sale (DAS) was signed and the original titles were for-mally transferred on June 10, 2015, at the national social insurance agency’s main of-fice in Pasay City, led by NCCA chairman Felipe M. de Leon Jr. and GSIS president and general manager Robert G. Vergara.

This marked a new chapter for the the-atre, a National Cultural Treasure. Accord-ing to De Leon, “this is a very touching, historic occasion and milestone because the Met is one of the best, most creative prod-ucts of Filipino artistic excellence.”

On the other hand, Vergara said: “GSIS is privileged to turn over this extraordinary asset to the NCCA. In more ways than one, we see this as an agreement handing the Met back to its rightful owners, the Filipino people.”

The NCCA credits the national gov-ernment and President Benigno Aquino III for this development. The Department of Budget and Management (DBM) ear-lier released the amount of P270 million from the National Endowment Fund for Culture and the Arts (NEFCA) for the ac-quisition of the Met. This was announced by DBM Secretary Florencio Abad in late May of this year.

“The Met was once a testament to the richness of Philippine culture and artistry, but decades of neglect brought this beauti-ful landmark into serious disrepair,” he stat-ed. “The Aquino administration, through the NCCA, has taken the first step to re-storing the MET to its former glory. It will take some time, but we are confident that the NCCA has the capacity to take on such a formidable task.”

“We cannot claim to pursue national

2015 • Number 2 • Agung 17

development if we fail at preserving our cul-ture and heritage,” he added.

According to the NCCA, the purchase of the Met is an important initial step to-wards the fullest conservation of the prop-erty by the NCCA in coordination with the concerned cultural agencies, commensurate with its status as a National Cultural Trea-sure and National Historical Landmark.

Additionally, the NCCA Board of Commissioners expresses that there is need for the Met, described as “a great architec-tural landmark of the artistic and cultural creativity of the Filipino people,” to be re-stored according to the highest standards of heritage conservation: “This will indeed be an iconic building of Filipino heritage that affirms the vision of the NCCA that Filipino culture is a wellspring of global and national well being. Restoring the Met is befitting a national treasure that eventu-ally would be an NCCA office for onserva-tion and a center for arts and culture for use by the nearby students and the general public.”

Glory and HistoryIn the district of Ermita, among fly-

overs, bridges, the fumes of traffic, parks and other buildings, the Metropolitan Theater presently stands out with its mot-ley of colors. The facade has a curving top crowned with pinnacles, colored glass win-dow and iron grills depicting stylized birds-of-paradise.

The Met was inaugurated on Decem-ber 10, 1931, designed by prominent ar-chitect Juan Arellano (April 25, 1888-De-cember 5, 1960). Having studied in the United States as one of the first pensionados in architecture, Arellano was influenced by the neoclassical and eclectic styles, which are evident in his major works such as the Legislative Building, built in 1926 and now housing the National Museum of the Phil-ippines (NM), and the Manila Central Post Office Building, also built in1926, with its impressive portico with Ionic columns. He also designed the Central United Methodist Church (1932) and the Negros Occidental Provincial Capitol (1936) in Bacolod City.

To many people, Arellano is known for the Met. Veering away from styles he was known for, the Met is in the Art Deco style. He was sent to the United States to study under Thomas W. Lamb, American theatre design expert, of Shreve and Lamb. In de-signing the theatre, it is said that Arellano was inspired by the phrase, “On the wings

of song.” The Met also exem-plifies his belief in incorporat-ing native art forms and motifs in designs.

The idea for building a theater in Manila was devel-oped in 1924. A theatre existed in the area before, the Teatro del Príncipe Alfonso XII, built in 1862 at the Plaza Arroceros but burnt down in 1876. With approval from the Philippine Legislature, 8,239.58 square meters of the Mehan Garden were allotted for the new the-ater and construction started in 1930.

With a program of mu-sic, drama and film, the Met opened the following year and was immediately hailed as an architectural achievement, both mod-ern and romantic. Local motifs were used, particularly images from Philippine flora. A frieze of mango fruits and leaves, for ex-ample, adorned the ceiling. Local flora and fauna as well were depicted in the stained-glass central window of the facade which served as signage and a way to bring in natural light to the lobby. The walls were curving and sported patches of colors re-sembling batik patterns. Inside, there were lamps of capiz shells and pillars in the shape of banana leaves. Colorful walls, bas reliefs and sculptures were interspersed inside the theater.

Other prominent artists contributed to the grandeur of the Met. At the main lobby were sculptures of Adam and Eve by Italian sculptor Francesco Riccardo Monti, who lived in Manila from 1930 up to his death in 1958. At the balcony overlooking the entrance were National Artist Fernando Amorsolo’s murals The Dance and History of Music as well as Monti’s other statues. Sculptor Isabelo Tampingco made the carv-ings of local flora in the interiors. Arellano’s brother, Arcadio, painted images of local flora in the main auditorium.

With the auditorium’s original capac-ity of 1,670, the Met hosted performances of zarzuelas, operas, concerts and foreign classics up to the Japanese occupation. The works of National Artists Antonio Bue-naventura and Nicanor Abelardo have also been performed at the Met.

In World War II, during the Battle for the Liberation of Manila in 1945, the Met suffered damages, and thus began its dete-

rioration and neglect. With the US Rehabilitation Act of 1946, the Met was repaired, but it was not able to bring back its glory days. The build-ing was eventually used by dif-ferent agencies and sometimes misused.

There were several efforts in restoration and rehabilita-tion. In the 1970s, then First Lady Imelda R. Marcos led an effort to restore the Met. The National Historical Institute, presently the National Histori-cal Commission of the Philip-pines (NHCP), declared it a National Historical Landmark in 1973. A restoration was conducted under the super-vision of Arellano’s nephew,

Otilio Arellano, and the Met was inaugu-rated on February 4, 1978. Kabataang Ba-rangay staged a show tracing the roots of the Filipino people through poetry, song and dance called Isang Munting Alamat. Up un-til the 1990s, performances were staged at the Met including the musical adaptations of Jose Rizal’s novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo by Ryan Cayabyab and Na-tional Artist Bienvenido Lumbrera in 1995. But it was eventually closed in 1996 after prolonged disuse.

Already falling into neglect and dis-repair, the Met saw another effort in res-toration. In 2004, then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo released P100 million from NEFCA for it, and the NCCA, led by executive director Cecile Guidote-Alvarez the city of Manila and the GSIS signed a tri-partite agreement to rehabilitate the theater.

The project also received support from the non-government and private sector, par-ticularly from the entertainment industry led by showbiz veteran German Moreno.

In 2007, the newly-formed Manila Historical and Heritage Commission came in to manage and supervise the restoration. This effort led to a “soft opening” on April 29, 2010, with the performance of a senaku-lo, a performance from Pilita Corrales and an excerpt from the original zarzuela Baler sa Puso Ko by Isagani Cruz.

The National Museum declared the Met a National Cultural Treasure on the same year on June 23.

Rock band Wolfgang was able to hold a concert in 2011.

However, it was closed down again

18 Agung • Number 2 • 2015