Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354 Published online 7 July 2009 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/uog.6415 Adding a single CA 125 measurement to ultrasound imaging performed by an experienced examiner does not improve preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses L. VALENTIN*, D. JURKOVIC†, B. VAN CALSTER‡, A. TESTA§, C. VAN HOLSBEKE¶, T. BOURNE¶**, I. VERGOTE¶, S. VAN HUFFEL‡ and D. TIMMERMAN¶ *Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Malm ¨ o University Hospital, Lund University, Malm ¨ o, Sweden, †Early Pregnancy and Gynaecology Assessment Unit, King’s College Hospital and **Imperial College, Hammersmith Campus, London, UK, ‡Department of Electrical Engineering, ESAT-SISTA, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and ¶Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospitals KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium and §Istituto di Clinica Ostetrica e Ginecologica, Universit ` a Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy KEYWORDS: CA 125 antigen; ovarian neoplasms; ultrasonography ABSTRACT Objectives To determine whether CA 125 measurement is superior to ultrasound imaging performed by an experienced examiner for discriminating between benign and malignant adnexal lesions, and to determine whether adding CA 125 to ultrasound examination improves diagnostic performance. Methods This is a prospective multicenter study (Interna- tional Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) study) conducted in nine European ultrasound centers in university hospi- tals. Of 1149 patients with an adnexal mass examined in the IOTA study, 83 were excluded. Of the remaining 1066 patients, 809 had CA 125 results available and were included. The patients underwent preoperative serum CA 125 measurements and transvaginal ultrasound exam- ination by an experienced ultrasound examiner blinded to CA 125 values. The examiner classified each mass as certainly or probably benign, difficult to classify, or prob- ably or certainly malignant. The outcome measure was the sensitivity and specificity with regard to malignancy of CA 125, ultrasound imaging and their combined use, the ‘gold standard’ being the histological diagnosis of the adnexal mass removed surgically within 120 days after the ultrasound examination. Results There were 242 (30%) malignancies. For 534 tumors judged to be certainly benign or certainly malignant by the ultrasound examiner the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound examination and CA 125 (≥ 35 U/mL indicating malignancy) were 97% vs. 86% (95% CI of difference, 4.7–17.2) and 99% vs. 79% (95% CI of difference, 15.7 – 24.2); for 209 tumors judged probably benign or probably malignant, sensitivity and specificity were 81% vs. 57% (95% CI of difference, 12.3–36.0) and 91% vs. 74% (95% CI of difference, 8.5–25.7); for 66 tumors that were difficult to classify, sensitivity and specificity were 57% vs. 39% (95% CI of difference, −9.7 to 41.1) and 74% vs. 67% (95% CI of difference, −14.6 to 27.7). Diagnostic performance deteriorated when CA 125 was used as a second-stage test after ultrasound examination. Conclusions Specialist ultrasound examination is supe- rior to CA 125 for preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses, irrespective of the diagnostic confidence of the ultrasound examiner; adding CA 125 to ultrasound does not improve diagnostic per- formance. Our results indicate that greater investment in education and training in gynecological ultrasound imaging would be of value. Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. INTRODUCTION CA 125 is a glycoprotein, defined by the antibody OC 12, that may be raised in patients with ovarian malig- nancy. Values ≥ 30 U/mL or ≥ 35 U/mL are often taken to indicate malignancy, but some suggest a higher cut- off (for example ≥ 65 U/mL) to indicate malignancy in premenopausal women 1–6 . The risk of malignancy in an adnexal mass can also be estimated on the basis of the results of a transvaginal ultrasound examina- tion. Subjective evaluation of ultrasound findings (pattern Correspondence to: Prof. L. Valentin, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Malm ¨ o University Hospital, SE 20502 Malm ¨ o, Sweden (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted: 23 February 2009 Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ORIGINAL PAPER

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354Published online 7 July 2009 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/uog.6415

Adding a single CA 125 measurement to ultrasound imagingperformed by an experienced examiner does not improvepreoperative discrimination between benign and malignantadnexal masses

L. VALENTIN*, D. JURKOVIC†, B. VAN CALSTER‡, A. TESTA§, C. VAN HOLSBEKE¶,T. BOURNE¶**, I. VERGOTE¶, S. VAN HUFFEL‡ and D. TIMMERMAN¶*Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Malmo University Hospital, Lund University, Malmo, Sweden, †Early Pregnancy andGynaecology Assessment Unit, King’s College Hospital and **Imperial College, Hammersmith Campus, London, UK, ‡Department ofElectrical Engineering, ESAT-SISTA, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and ¶Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University HospitalsKU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium and §Istituto di Clinica Ostetrica e Ginecologica, Universita Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy

KEYWORDS: CA 125 antigen; ovarian neoplasms; ultrasonography

ABSTRACT

Objectives To determine whether CA 125 measurementis superior to ultrasound imaging performed by anexperienced examiner for discriminating between benignand malignant adnexal lesions, and to determine whetheradding CA 125 to ultrasound examination improvesdiagnostic performance.

Methods This is a prospective multicenter study (Interna-tional Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) study) conductedin nine European ultrasound centers in university hospi-tals. Of 1149 patients with an adnexal mass examinedin the IOTA study, 83 were excluded. Of the remaining1066 patients, 809 had CA 125 results available and wereincluded. The patients underwent preoperative serumCA 125 measurements and transvaginal ultrasound exam-ination by an experienced ultrasound examiner blindedto CA 125 values. The examiner classified each mass ascertainly or probably benign, difficult to classify, or prob-ably or certainly malignant. The outcome measure wasthe sensitivity and specificity with regard to malignancyof CA 125, ultrasound imaging and their combined use,the ‘gold standard’ being the histological diagnosis of theadnexal mass removed surgically within 120 days afterthe ultrasound examination.

Results There were 242 (30%) malignancies. For 534tumors judged to be certainly benign or certainlymalignant by the ultrasound examiner the sensitivityand specificity of ultrasound examination and CA 125(≥ 35 U/mL indicating malignancy) were 97% vs. 86%(95% CI of difference, 4.7–17.2) and 99% vs. 79%

(95% CI of difference, 15.7–24.2); for 209 tumors judgedprobably benign or probably malignant, sensitivity andspecificity were 81% vs. 57% (95% CI of difference,12.3–36.0) and 91% vs. 74% (95% CI of difference,8.5–25.7); for 66 tumors that were difficult to classify,sensitivity and specificity were 57% vs. 39% (95% CIof difference, −9.7 to 41.1) and 74% vs. 67% (95%CI of difference, −14.6 to 27.7). Diagnostic performancedeteriorated when CA 125 was used as a second-stage testafter ultrasound examination.

Conclusions Specialist ultrasound examination is supe-rior to CA 125 for preoperative discrimination betweenbenign and malignant adnexal masses, irrespective of thediagnostic confidence of the ultrasound examiner; addingCA 125 to ultrasound does not improve diagnostic per-formance. Our results indicate that greater investmentin education and training in gynecological ultrasoundimaging would be of value. Copyright 2009 ISUOG.Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

INTRODUCTION

CA 125 is a glycoprotein, defined by the antibody OC12, that may be raised in patients with ovarian malig-nancy. Values ≥ 30 U/mL or ≥ 35 U/mL are often takento indicate malignancy, but some suggest a higher cut-off (for example ≥ 65 U/mL) to indicate malignancy inpremenopausal women1–6. The risk of malignancy inan adnexal mass can also be estimated on the basisof the results of a transvaginal ultrasound examina-tion. Subjective evaluation of ultrasound findings (pattern

Correspondence to: Prof. L. Valentin, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Malmo University Hospital, SE 20502 Malmo, Sweden(e-mail: [email protected])

Accepted: 23 February 2009

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ORIGINAL PAPER

346 Valentin et al.

recognition) by an experienced operator is highly accuratefor the prediction of malignancy7–10, and a correct spe-cific diagnosis can be made in many benign tumors, e.g.endometriomas or dermoid cysts7,10,11. Although ultra-sound imaging is an excellent method for classifyingadnexal masses, serum CA 125 is often measured as asecond-stage test to estimate the likelihood of malignancyin adnexal lesions detected by ultrasound examination.CA 125 may be used alone or incorporated in the riskof malignancy index (RMI)12. The RMI is calculatedas the product of the serum CA 125 level (U/mL), theultrasound scan result (expressed as a score of 0, 1 or3) and the menopausal status (1 if premenopausal and3 if postmenopausal); an RMI > 200 is often used toindicate malignancy12. We have questioned the valueof using CA 125 for estimating the risk of malig-nancy in adnexal tumors when the results of ultrasoundexaminations performed by experienced examiners areavailable13,14. However, when characterizing an adnexalmass, ultrasound examiners may have a variable degreeof confidence in their assessment9. It is possible thatadding information on CA 125 could be superior to pat-tern recognition – or improve diagnostic performance ifadded to pattern recognition – at least when the ultra-sound examiner is uncertain.

Our aim was to determine whether CA 125 measure-ment is superior to ultrasound imaging performed by anexperienced examiner for the preoperative discriminationbetween benign and malignant adnexal lesions, in partic-ular for masses thought difficult to characterize as benignor malignant on the basis of ultrasound findings, andto determine whether adding information on CA 125 toultrasound findings as a second-stage test improves diag-nostic performance. Because CA 125 is an important vari-able in the RMI we also wanted to compare the diagnosticperformance of pattern recognition with that of RMI.

METHODS

We used the prospectively collected information in theInternational Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) database.The IOTA study is a prospective multicenter studycomprising nine European ultrasound centers in uni-versity hospitals. It was approved by the local ethicscommittees and has been described in detail in a previ-ous publication15, which records the ultrasound centersinvolved, the number of patients, and the number ofbenign and malignant tumors that each center contributedto the study. The procedures followed were in accordancewith the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983.Informed consent was obtained from each participantin the study. The design of the IOTA study is brieflyoutlined below.

Consecutive patients referred to the participatingultrasound centers because of at least one adnexal masswere considered for inclusion in the study providedthat the clinical history and ultrasound findings did notsuggest that the mass was a functional cyst. The patientsconsidered for inclusion underwent gray-scale and color

Doppler ultrasonography by an experienced ultrasoundexaminer using high-quality ultrasound equipment, astandardized examination technique, and standardizedterms and definitions16. A transvaginal scan wasperformed in all cases. Transabdominal sonography wasadded to examine large masses that could not be seenin their entirety using a transvaginal probe. On the basisof subjective evaluation of gray-scale and color Dopplerfindings (pattern recognition), the ultrasound examinerclassified each mass as being certainly benign, probablybenign, difficult to classify as benign or malignant(complete uncertainty), probably malignant or certainlymalignant. Even when the examiner found the massdifficult to classify, he/she was obliged to state whetherthe mass was more likely to be benign or malignant.Whenever possible the examiner also suggested a specifichistological diagnosis (e.g. endometrioma, dermoid cystor hydrosalpinx). The ultrasound examiner had noknowledge of the patient’s serum CA 125 value whensuggesting a diagnosis. Only patients with a histologicaldiagnosis of the mass obtained by surgery within 120 daysafter the ultrasound examination were included.

In this analysis, a woman was considered to bepostmenopausal if she reported absence of menstruationfor at least 1 year after the age of 40 years providedthat the amenorrhea was not explained by pregnancy,medication or disease. Women aged ≥ 50 years whohad undergone a hysterectomy, for whom the time ofmenopause could not be determined, were also defined aspostmenopausal. Women with menstrual periods duringthe year before the examination and women younger than50 years who had undergone a hysterectomy withoutbilateral oophorectomy were defined as premenopausal.

The participating centers were encouraged to measurethe level of serum CA 125 in peripheral blood from allpatients, but the availability of CA 125 results was nota requirement for inclusion in the IOTA study. Second-generation immunoradiometric assay kits for CA 125(CA 125 II)17 from five companies were used (Cento-cor, Malvern, PA, USA; Cis-Bio, Gif-sur-Yvette, France;Abbott Axsym system, REF 3B41-22, Abbott Laborato-ries Diagnostic Division, Abbott Park, IL, USA; Immuno-l-analyser, Bayer Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY, USA; orVidas, bioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). All kits usedthe OC 125 antibody. CA 125 results are expressed inU/mL.

The reference standard was the histology of thesurgically removed adnexal mass. Ultrasound imaging andCA 125 results were not concealed to the pathologistsmaking the histopathological diagnosis. Tumors wereclassified according to the criteria recommended by theInternational Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics18.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). In the statisticalanalyses, borderline tumors were classified as malignant.The diagnostic performance in terms of accuracy,

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

Preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses 347

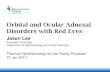

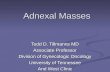

sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihoodratios with regard to malignancy of the followingfive diagnostic methods was determined: (1) subjectiveevaluation by the ultrasound examiner, i.e. patternrecognition; (2) serum CA 125; (3) a policy wherebyboth pattern recognition and CA 125 must suggest abenign diagnosis for a benign diagnosis to be made(Figure 1), a strategy that would increase sensitivity at theexpense of reduced specificity; (4) a policy whereby bothpattern recognition and CA 125 must suggest a malignantdiagnosis for a malignant diagnosis to made (Figure 2),a strategy that would increase specificity at the expenseof reduced sensitivity; and (5) RMI using the algorithmof Jacobs et al.12. The CIs for differences in sensitivityand specificity between pattern recognition and analysisof CA 125, and between pattern recognition and RMI,were calculated using a score interval method, i.e. method10 in Newcombe19. The CIs for likelihood ratios werecalculated using the Cox–Hinkley–Miettinen–Nurminenmethod20.

RESULTS

Recruitment of patients to the IOTA study started inJune 1999 and ended in June 2001. Of the 1149 patientswith an adnexal mass examined in the IOTA study, 83were excluded15. Of the remaining 1066 patients, 809(76%) had available CA 125 results and were includedin the present analysis. These 809 patients have alsobeen used in two other publications regarding the use-fulness of CA 125 when assessing adnexal tumors13,14.Table 1 shows demographic background data, histologi-cal diagnoses and results of subjective estimation of riskof malignancy by the ultrasound examiner both for the809 patients included and the 257 patients excluded fromthe present analysis because of missing CA 125 results.

First step Subjective assessment

Malignant Benign

Second step Serum CA 125

Malignant

< Cut-off

Benign

≥ Cut-off

Figure 1 Decision tree illustrating the use of serum CA 125 as asecond-stage test in cases where subjective assessment of ultrasoundfindings (pattern recognition) by an ultrasound examiner predicts abenign tumor. This strategy will increase sensitivity at the expenseof reduced specificity.

The patients excluded were younger, and more of themhad benign tumors, in particular endometriomas, but thediagnostic performance of the ultrasound examiner wassimilar in the patients included and those excluded (sen-sitivity 88% in patients included vs. 83% in the patientsexcluded; specificity 95% vs. 96%).

The histopathological diagnoses according to the diag-nostic confidence of the ultrasound examiner when usingpattern recognition are shown in Table 2. The ultrasoundexaminer classified 534 (66%) tumors as certainly benignor certainly malignant, 209 (26%) tumors as probablybenign or probably malignant and 66 (8%) tumors asimpossible to classify as benign or malignant (‘uncertain’).Endometriomas were more common among tumors thatthe ultrasound examiner was completely confident werebenign or malignant, whereas borderline tumors, rarebenign tumors, cystadenomas and fibromas were morecommon in the group of tumors that the ultrasound exam-iner was less confident or completely uncertain about.

Table 3 shows the diagnostic performance of patternrecognition and serum CA 125 depending on the confi-dence of the ultrasound examiner when CA 125 values≥ 35 U/mL were used to indicate malignancy. Patternrecognition was superior to CA 125 irrespective of theconfidence with which the ultrasound examiner suggestedwhether a tumor was benign or malignant. None of thetested cut-off values for CA 125 (30 U/mL, 35 U/mL,65 U/mL, 100 U/mL, 200 U/mL, 400 U/mL, 1000 U/mL)was superior to pattern recognition in any of the threeconfidence groups (certainly benign or certainly malig-nant, probably benign or probably malignant, completelyuncertain), and this was true of both premenopausaland postmenopausal patients (Tables S1 and S2 online).When the ultrasound examiner was uncertain whether thetumor was benign or malignant both pattern recognitionand CA 125 were poor diagnostic tests.

First step Subjective assessment

Malignant Benign

Second step Serum CA 125

≥ Cut-off

Malignant Benign

< Cut-off

Figure 2 Decision tree illustrating the use of serum CA 125 as asecond-stage test in cases where subjective assessment of ultrasoundfindings (pattern recognition) by an ultrasound examiner predicts amalignant tumor. This strategy will increase specificity at theexpense of reduced sensitivity.

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

348 Valentin et al.

Table 1 Demographic background data, histological diagnoses, estimation of risk of malignancy by experienced ultrasound examiners whoused pattern recognition, and rate of correct diagnoses with regard to malignancy when using pattern recognition in women included in andexcluded from this analysis

Included women

VariableExcluded women

(n = 257)All

(n = 809)Premenopausal

(n = 445)Postmenopausal

(n = 364)

Mean age (years) 41.9 ± 14.5 48.8 ± 15.6 37.4 ± 9.1 62.8 ± 9.4Postmenopausal 68 (26.5) 364 (45.0)Histological diagnosis

All benign tumors 233 (90.7) 567 (70.1) 359 (80.7) 208 (57.1)Endometrioma 84 (32.7) 128 (15.8) 123 (27.6) 5 (1.4)Dermoid/teratoma 44 (17.1) 83 (10.3) 68 (15.3) 15 (4.1)Simple cyst 15 (5.8) 84 (10.4) 39 (8.8) 45 (12.4)Functional cyst 13 (5.1) 15 (1.9) 12 (2.7) 3 (0.8)Hydrosalpinx 9 (3.5) 15 (1.9) 12 (2.7) 3 (0.8)Peritoneal pseudocyst 4 (1.6) 4 (0.5) 3 (0.7) 1 (0.3)Abscess 6 (2.3) 19 (2.3) 13 (2.9) 6 (1.6)Fibroma 8 (3.1) 29 (3.6) 9 (2.0) 20 (5.5)Cystadenoma 34 (13.2) 102 (12.6) 38 (8.5) 64 (17.6)Mucinous cystadenoma 14 (5.4) 80 (9.9) 40 (9.0) 40 (11.0)Rare benign tumor 2 (0.8) 8 (1.0) 2 (0.4) 6 (1.6)

All malignant tumors 24 (9.3) 242 (29.9) 86 (19.3) 156 (42.9)Primary invasive 17 (6.6) 127 (15.7) 32 (7.2) 95 (26.1)

Stage I 9 (3.5) 33 (4.1) 10 (2.2) 23 (6.3)Stage II 2 (0.8) 10 (1.2) 2 (0.4) 8 (2.2)Stage III 4 (1.6) 69 (8.5) 17 (3.8) 52 (14.3)Stage IV 2 (0.8) 15 (1.9) 3 (0.7) 12 (3.3)

Borderline 3 (1.2) 52 (6.4) 27 (6.1) 25 (6.9)Metastatic 4 (1.6) 38 (4.7) 13 (2.9) 25 (6.9)Rare primary invasive 0 (0) 25 (3.1) 14 (3.1) 11 (3.0)

Risk estimation by ultrasound examinerCertainly benign 168 (65.4) 384 (47.5) 276 (62.0) 108 (29.7)Probably benign 41 (16.0) 140 (17.3) 75 (16.9) 65 (17.9)Unclassifiable 24 (9.3) 66 (8.2) 26 (5.8) 40 (11.0)Probably malignant 14 (5.4) 69 (8.5) 26 (5.8) 43 (11.8)Certainly malignant 10 (3.9) 150 (18.5) 42 (9.4) 108 (29.7)

Correctly classified with regard to malignancy 244 (94.9) 752 (93.0) 421 (94.6) 331 (90.9)by ultrasound examinerBenign masses† 224 (96.1) 538 (94.9) 351 (97.8) 187 (89.9)Malignant masses‡ 20 (83.3) 214 (88.4) 70 (81.4) 144 (92.3)

Women included in this study had CA 125 serum levels available. Values are mean ± SD or n (%). †Numbers in parentheses are percentagesof all benign masses. ‡Numbers in parentheses are percentages of all malignant masses. Reproduced from J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99:1706–1714. Published with permission from Oxford University Press.

Table 4 shows the diagnostic performance of patternrecognition and RMI depending on the confidence ofthe ultrasound examiner when RMI > 200 was used toindicate malignancy. Pattern recognition was superiorto RMI irrespective of the diagnostic confidence of theultrasound examiner, but when the ultrasound examinerwas uncertain about the character of the mass both patternrecognition and RMI were poor diagnostic methods.Similar results were obtained when RMI > 100 was usedto indicate malignancy.

The effects of using CA 125 as a second-stage test afterthe ultrasound examiner had suggested a diagnosis areshown in Tables 5 and 6. The outcome of a strategy inwhich both pattern recognition and CA 125 must suggesta benign diagnosis for a benign diagnosis to be made isshown in Table 5, and the outcome of a strategy in whichboth pattern recognition and CA 125 must suggest amalignancy for a malignant diagnosis to be made is shown

in Table 6. The strategy requiring pattern recognition andCA 125 to be concordant resulted in more tumors beingmisclassified and in diagnostic performance deteriorating.This was true of both premenopausal and postmenopausalpatients and irrespective of the diagnostic confidence ofthe ultrasound examiner (Tables S3–S8 online show theseresults in detail).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have shown that an ultrasoundexamination performed and interpreted by an experiencedoperator is superior to the analysis of serum CA 125irrespective of the diagnostic confidence of the ultrasoundexaminer when he/she suggests that a lesion is benign ormalignant, and that this is true in both premenopausaland postmenopausal patients. We were disappointed to

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

Preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses 349

Table 2 Histological diagnoses with regard to the diagnostic confidence of the ultrasound examiner when he/she suggested a diagnosis ofbenignity or malignancy

Diagnostic confidence of ultrasound examiner (n (%))

Histologicaldiagnosis

Certainly benignor certainly malignant

(n = 534)

Probably benignor probably malignant

(n = 209)Uncertain(n = 66)

Total (n (%))(n = 809)

All benign tumors 384 (71.9) 140 (67.0) 43 (65.2) 567Endometrioma 105 (19.7) 19 (9.1) 4 (6.1) 128Dermoid/teratoma 68 (12.7) 9 (4.3) 6 (9.1) 83Simple or functional cyst 70 (13.1) 23 (11.0) 6 (9.1) 99Extraovarian mass 13 (2.4) 6 (2.9) 0 (0) 19Abscess/PID 11 (2.1) 6 (2.9) 2 (3.0) 19Fibroma 11 (2.1) 13 (6.2) 5 (7.6) 29Cystadenoma 104 (19.5) 59 (28.2) 19 (28.8) 182Rare benign tumor 2 (0.4) 5 (2.4) 1 (1.5) 8

All malignant tumors 150 (28.1) 69 (33.0) 23 (34.8) 242Primary invasive 94 (17.6) 28 (13.4) 5 (7.6) 127

Stage I 19 (3.6) 12 (5.7) 2 (3.0) 33Serous 8 3 0 11Mucinous 2 3 0 5Endometrioid 5 3 0 8Other 4 3 2 9

Stage II–IV 75 (14.0) 16 (7.7) 3 (4.5) 94Serous 47 10 2 59Mucinous 3 1 0 4Endometrioid 12 1 0 13Other 13 4 1 18

Borderline 17 (3.2) 23 (11.0) 12 (18.2) 52Serous 9 9 6 24Mucinous 6 11 5 22Other 2 3 1 6

Rare primary invasive 14 (2.6) 9 (4.3) 2 (3.0) 25Metastatic 25 (4.7) 9 (4.3) 4 (6.1) 38

PID, pelvic inflammatory disease.

find that measurements of serum CA 125 were not helpfulin the characterization of tumors considered difficult toclassify by ultrasound imaging. This was the case howeverthe CA 125 values were used and whatever cut-off valuewas tested. Pattern recognition was also superior to RMI.However, all three methods performed poorly in the groupof ‘difficult tumors’. The particular mix of tumors in thisgroup may explain this. For example, borderline tumorswere clearly over-represented among the difficult tumors,and borderline tumors are often misclassified both bypattern recognition21 and by CA 12514. Because CA 125is an important variable in the RMI, RMI is also likely tomisclassify borderline tumors.

It is important to emphasize that our results arerepresentative of ultrasound examinations carried outand interpreted by very experienced examiners usinghigh-quality ultrasound equipment. Almost 80% of theexaminations in the study had been carried out byLevel III examiners defined using the terminology ofthe European Federation of Ultrasound in Medicineand Biology (EFSUMB), i.e. the examiners worked intertiary referral centers, had an academic record, and ahigh level of experience and expertise22. Some of themhad performed up to 16 000 gynecological ultrasoundexaminations by the start of the study. Moreover, they

had a special interest in the use of ultrasound imaging tocharacterize adnexal tumors. It cannot be excluded thatCA 125 would improve the diagnostic performance ifit were added to an ultrasound examination carried outand interpreted by a less experienced examiner, or thatCA 125 or RMI would be superior to such an ultrasoundexamination. On the other hand, even examiners withvery limited experience of only 200–300 gynecologicalultrasound examinations performed under supervisionwere able to correctly classify most adnexal tumors asbenign or malignant when presented with representativeultrasound images8.

In previous publications using the same patients asin this study we have shown that adding informationon CA 125 to clinical and ultrasound information doesnot improve the diagnostic performance of mathematicalmodels constructed to calculate the risk of malignancyin adnexal masses13, and that ultrasound examinationperformed by an experienced examiner is superior tothe analysis of serum CA 125 for distinguishing benignfrom malignant adnexal masses in each of 15 specifichistological subgroups of adnexal tumors14. However,we want to emphasize that we have examined onlythe diagnostic performance of a single measurement of

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

350 Valentin et al.

Tab

le3

Dia

gnos

tic

perf

orm

ance

ofpa

tter

nre

cogn

itio

nan

dse

rum

CA

125

depe

ndin

gon

the

confi

denc

eof

the

ultr

asou

ndex

amin

er

Pat

tern

reco

gnit

ion

CA

125

Dif

fere

nce

inD

iffe

renc

ein

Con

fiden

ceof

ultr

asou

ndex

amin

erA

ccur

acy

(%(n

))Se

nsit

ivit

y(%

(n))

Spec

ifici

ty(%

(n))

LR

+(9

5%C

I)L

R−

(95%

CI)

Acc

urac

y(%

(n))

Sens

itiv

ity

(%(n

))Sp

ecifi

city

(%(n

))L

R+

(95%

CI)

LR

−(9

5%C

I)se

nsit

ivit

y(9

5%C

I)sp

ecifi

city

(95%

CI)

Cer

tain

lybe

nign

orce

rtai

nly

9897

9974

.20.

034

8186

794.

080.

1810

.719

.8m

alig

nant

(n=

534)

(524

/534

)(1

45/1

50)

(379

/384

)(3

2.1

to>

100)

(0.0

2–0

.08)

(432

/534

)(1

29/1

50)

(303

/384

)(3

.3–5

.0)

(0.1

2–0

.26)

(4.7

–17.

2)(1

5.7

–24.

2)Pr

obab

lybe

nign

orpr

obab

ly88

8191

8.7

0.20

868

5774

2.14

0.59

24.6

17.1

mal

igna

nt(n

=20

9)(1

83/2

09)

(56/

69)

(127

/140

)(5

.2–1

4.9)

(0.1

3–0

.33)

(142

/209

)(3

9/69

)(1

03/1

40)

(1.5

–3.0

)(0

.43

–0.7

7)(1

2.3

–36.

0)(8

.5–2

5.7)

Com

plet

ely

unce

rtai

n68

5774

2.2

0.58

458

3967

1.20

0.90

17.4

7.0

(dif

ficul

ttu

mor

)(n

=66

)(4

5/66

)(1

3/23

)(3

2/43

)(1

.2–4

.1)

(0.3

4–0

.91)

(38/

66)

(9/2

3)(2

9/43

)(0

.6–2

.3)

(0.5

8–1

.30)

(−9.

7to

41.1

)(−

14.6

to27

.7)

CA

125

valu

es≥3

5U

/mL

indi

cate

dm

alig

nanc

y.L

R+,

posi

tive

likel

ihoo

dra

tio;

LR

−,ne

gati

velik

elih

ood

rati

o.

Tab

le4

Dia

gnos

tic

perf

orm

ance

ofpa

tter

nre

cogn

itio

nan

dri

skof

mal

igna

ncy

inde

x(R

MI)

depe

ndin

gon

the

confi

denc

eof

the

ultr

asou

ndex

amin

er

Pat

tern

reco

gnit

ion

RM

ID

iffe

renc

ein

Dif

fere

nce

inC

onfid

ence

oful

tras

ound

exam

iner

Acc

urac

y(%

(n))

Sens

itiv

ity

(%(n

))Sp

ecifi

city

(%(n

))L

R+

(95%

CI)

LR

−(9

5%C

I)A

ccur

acy

(%(n

))Se

nsit

ivit

y(%

(n))

Spec

ifici

ty(%

(n))

LR

+(9

5%C

I)L

R−

(95%

CI)

sens

itiv

ity

(95%

CI)

spec

ifici

ty(9

5%C

I)

Cer

tain

lybe

nign

orce

rtai

nly

9897

9974

.20.

034

9283

9517

.80.

175

13.3

3.4

mal

igna

nt(n

=53

4)(5

24/5

34)

(145

/150

)(3

79/3

84)

(32.

1to

>10

0)(0

.02

–0.0

8)(4

91/5

34)

(125

/150

)(3

66/3

84)

(11.

4–2

8.1)

(0.1

2–0

.25)

(7.6

–19.

9)(1

.2–6

.0)

Prob

ably

beni

gnor

prob

ably

8881

918.

740.

208

7652

874.

060.

549

29.0

3.6

mal

igna

nt(n

=20

9)(1

83/2

09)

(56/

69)

(127

/140

)(5

.2–1

4.9)

(0.1

3–0

.33)

(158

/209

)(3

6/69

)(1

22/1

40)

(2.5

–6.6

)(0

.42

–0.6

9)(1

5.4

–41.

2)(−

3.4

to10

.7)

Com

plet

ely

unce

rtai

n68

5774

2.21

0.58

458

2674

1.02

0.99

330

.40.

0(d

iffic

ult

tum

or)

(n=

66)

(45/

66)

(13/

23)

(32/

43)

(1.2

–4.1

)(0

.34

–0.9

1)(3

8/66

)(6

/23)

(32/

43)

(0.4

–2.3

)(0

.7–1

.3)

(2.4

–52.

6)(−

20.9

to20

.9)

RM

I>

200

indi

cate

dm

alig

nanc

y.L

R+,

posi

tive

likel

ihoo

dra

tio;

LR

−,ne

gati

velik

elih

ood

rati

o.

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

Preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses 351

Table 5 Diagnostic performance when using CA 125 as a second-stage test after ultrasound examination (requiring the results of bothpattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate a benign diagnosis for a benign diagnosis to be made)

Population Strategy (cut-off*)Accuracy

(%)Sensitivity

(%)Specificity

(%) LR+ LR−

All (n = 809) Subj 93.0 88.4 94.9 17.31 0.12Subj −/CA 125 (30) 75.3 92.6 67.9 2.88 0.11Subj −/CA 125 (35) 78.6 91.7 73.0 3.40 0.11Subj −/CA 125 (65) 86.8 90.9 85.0 6.06 0.11Subj −/CA 125 (100) 89.7 89.7 89.8 8.77 0.12Subj −/CA 125 (200) 91.7 89.3 92.8 12.35 0.12Subj −/CA 125 (400) 92.6 88.4 94.4 15.68 0.12Subj −/CA 125 (1000) 92.8 88.4 94.7 16.72 0.12

Premenopause (n = 445) Subj 94.6 81.4 97.8 36.50 0.19Subj −/CA 125 (30) 69.9 89.5 65.2 2.57 0.16Subj −/CA 125 (35) 73.7 87.2 70.5 2.95 0.18Subj −/CA 125 (65) 85.6 86.0 85.5 5.94 0.16Subj −/CA 125 (100) 90.3 83.7 91.9 10.36 0.18Subj −/CA 125 (200) 93.0 82.6 95.5 18.51 0.18Subj −/CA 125 (400) 94.6 81.4 97.8 36.50 0.19Subj −/CA 125 (1000) 94.6 81.4 97.8 36.50 0.19

Postmenopause (n = 364) Subj 90.9 92.3 89.9 9.14 0.09Subj −/CA 125 (30) 81.9 94.2 72.6 3.44 0.08Subj −/CA 125 (35) 84.6 94.2 77.4 4.17 0.07Subj −/CA 125 (65) 88.2 93.6 84.1 5.90 0.08Subj −/CA 125 (100) 89.0 92.9 86.1 6.67 0.08Subj −/CA 125 (200) 90.1 92.9 88.0 7.73 0.08Subj −/CA 125 (400) 90.1 92.3 88.5 8.00 0.09Subj −/CA 125 (1000) 90.7 92.3 89.4 8.72 0.09

LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; Subj, subjective evaluation of ultrasound findings; Subj −/CA 125, requiringthe results of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate a benign diagnosis for a benign diagnosis to be made. *CA 125 cut-off inU/mL to indicate malignancy.

CA 125. It is possible that serial measurements of CA 125would have better diagnostic performance than a singlemeasurement. Some might argue that borderline tumorsshould be included in the group of benign tumors whencomparing the ability of pattern recognition and CA 125to discriminate between benign and malignant tumors,because some oncologists regard borderline tumors asdisease with a good prognosis. However, even whenincluding the borderline tumors in the benign group,pattern recognition was superior to CA 125. Using aCA 125 cut-off value of 30 U/mL the sensitivity of CA 125and pattern recognition was 96% (182/190) vs. 85%(161/190) and the specificity 90% (558/619) vs. 70%(433/619), and pattern recognition remained superior toCA 125 even when using higher CA 125 cut-off values toindicate malignancy.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. Table 1reveals a bias whereby serum CA 125 is more likely to havebeen measured in women with lesions that were suspectedof being malignant by the ultrasound examiner. We donot believe that this invalidates our conclusions, becausein all likelihood serum CA 125 would have performedmore poorly in the patients excluded than in the patientsincluded, given the large proportion of endometriomasin the group excluded. An experienced ultrasound exam-iner almost always classifies endometriomas correctly,whereas CA 125 tends to misclassify endometriomasas malignancies14. We cannot rule out, of course, thatCA 125 in addition to ultrasound pattern recognition in

patients without endometriomas may be helpful. Anotherlimitation of our study is that five CA 125 kits were usedto assess the level of serum CA 125. However, this reflectsclinical reality, and there is some evidence that the varia-tion in CA 125 resulting from use of different kits is notlarge23,24.

The preoperative assessment of adnexal tumors remainsa challenge. Advances in surgery have provided newtreatment options for women with ovarian tumors, butthese new methods are useful only if the preoperativediagnosis is correct. Rupture of a Stage 1 ovariancancer during an operation may worsen the prognosis25,and incorrect preoperative classification of a tumoras benign may increase the risk of this happening.Currently, ultrasound examination by an experiencedoperator using pattern recognition seems to be thebest method for discriminating between benign andmalignant adnexal tumors before surgery9,10,14. Theability to discriminate between benign and malignantmasses using pattern recognition increases with theexperience of the ultrasound examiner8. We believe thattime and money could be saved both for patients andhealth services if there was consensus that patients withadnexal masses should undergo Level II or Level IIIultrasound imaging before deciding on management, thatis before referring the patient to a gynecological oncologycenter, and that greater investment in education andtraining in gynecological ultrasound examination wouldbe of value. This is also supported by the results of

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

352 Valentin et al.

Table 6 Diagnostic performance when using CA 125 as a second-stage test after ultrasound examination (requiring the results of bothpattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate malignancy for a malignant diagnosis to be made)

Population Strategy (cut-off*)Accuracy

(%)Sensitivity

(%)Specificity

(%) LR+ LR−

All Subj 93.0 88.4 94.9 17.31 0.12(n = 809) Subj +/CA 125 (30) 90.1 71.5 98.1 36.85 0.29

Subj +/CA 125 (35) 90.0 69.8 98.6 49.5 0.31Subj +/CA 125 (65) 87.9 61.6 99.1 69.97 0.39Subj +/CA 125 (100) 86.3 55.8 99.3 78.58 0.45Subj +/CA 125 (200) 83.2 44.6 99.6 127.5 0.56Subj +/CA 125 (400) 79.7 32.6 99.8 181.3 0.67Subj +/CA 125 (1000) 75.2 17.4 99.8 96.4 0.83

Premenopause Subj 94.6 81.4 97.8 36.50 0.19(n = 445) Subj +/CA 125 (30) 91.2 58.1 99.2 69.21 0.42

Subj +/CA 125 (35) 91.2 57.0 99.4 102 0.43Subj +/CA 125 (65) 89.2 45.3 99.7 162.0 0.55Subj +/CA 125 (100) 88.1 39.5 99.7 141.2 0.61Subj +/CA 125 (200) 86.1 27.9 100.0 Inf 0.72Subj +/CA 125 (400) 84.0 17.4 100.0 Inf 0.83Subj +/CA 125 (1000) 82.7 10.5 100.0 Inf 0.90

Postmenopause Subj 90.9 92.3 89.9 9.14 0.09(n = 364) Subj +/CA 125 (30) 88.7 78.8 96.2 20.48 0.22

Subj +/CA 125 (35) 88.5 76.9 97.1 26.7 0.24Subj +/CA 125 (65) 86.3 70.5 98.1 36.72 0.30Subj +/CA 125 (100) 84.1 64.7 98.6 44.96 0.36Subj +/CA 125 (200) 79.7 53.8 99.0 56.09 0.47Subj +/CA 125 (400) 74.5 41.0 99.5 85.48 0.59Subj +/CA 125 (1000) 65.9 21.2 99.5 44.06 0.79

Inf, infinity; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio; Subj, subjective evaluation of ultrasound findings;Subj +/CA 125, requiring the results of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate malignancy for a malignant diagnosis to be made.*CA 125 cut-off in U/mL to indicate malignancy.

a randomized controlled trial showing that improvedquality of ultrasonography had a measurable effect on themanagement of patients with suspected ovarian cancerin a tertiary gynecology cancer center, and resulted ina significant decrease in the number of major stagingprocedures and a shorter inpatient hospital stay26. TheEFSUMB has published guidelines on how much trainingand education in gynecological ultrasound imaging isneeded to obtain competence at different levels22, but theamount of training and experience needed to become goodat pattern recognition is likely to vary between individuals.

Unfortunately, even when performed by an experiencedexaminer, pattern recognition is not a good diagnosticmethod for ‘difficult tumors’, i.e. when the examineris uncertain about whether the mass is benign ormalignant, nor do logistic regression models to calculatethe risk of malignancy seem to help in these21. Suchdifficult masses comprise 7–10% of tumors currentlyconsidered appropriate to remove surgically21. From aclinical viewpoint some might be happy to include thesemasses in the ‘probably malignant’ group. However,it is possible that other diagnostic methods added toconventional gray-scale and Doppler ultrasound imagingas second-stage tests would be helpful in assessingthese difficult tumors; examples are evaluation of thevascular tree of tumors using three-dimensional powerDoppler ultrasound examination27, or semiquantificationof tumor perfusion using ultrasound contrast. Qualitativeevaluation of contrast-enhanced ultrasound examination

does not seem to improve diagnostic performance intumors with papillary projections28, which constitute asubgroup of difficult ovarian tumors21.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the research council ofthe Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium (GOA-AMBioRICS, CoE EF/05/006 Optimization in Engi-neering OPTEC); the Belgian Federal Science Pol-icy Office IUAP P6/04 (DYSCO, ‘Dynamical systems,control and optimization’, 2007-2011); the EU: BIOPAT-TERN (FP6-2002-IST 508803); ETUMOUR (FP6-2002-LIFESCIHEALTH 503094); Healthagents (IST–2004–27214); the Swedish Medical Research Council (grantsnumbers K2001-72X-11605-06A, K2002-72X-11605-07B, K2004-73X-11605-09A and K2006-73X-11605-11-3); funds administered by Malmo University Hospital;Allmanna Sjukhusets i Malmo Stiftelse for bekampandeav cancer (the Malmo General Hospital Foundationfor fighting against cancer); and ALF-medel (a Swedishgovernmental grant).

APPENDIX

IOTA Steering CommitteeDirk Timmerman, Lil Valentin, Tom Bourne, Antonia C.Testa, Sabine Van Huffel, Ignace Vergote

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

Preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant adnexal masses 353

IOTA principal investigators (alphabetical order)Jean-Pierre Bernard, Maurepas, FranceEnrico Ferrazzi, Milan, ItalyDavor Jurkovic, London, UKAndrea Lissoni, Monza, ItalyUlrike Metzger, Paris, FranceDario Paladini, Naples, ItalyAntonia Testa, Rome, ItalyDirk Timmerman, Leuven, BelgiumLil Valentin, Malmo, Sweden

Other IOTA contributorsFabrice Lecuru, Paris, FranceFrancesco Leone, Milan, ItalyBen Van Calster, Leuven, BelgiumCaroline Van Holsbeke, Leuven, BelgiumSabine Van Huffel, Leuven, BelgiumDominique Van Schoubroeck, Leuven, BelgiumGerardo Zanetta (deceased), Monza, Italy

REFERENCES

1. Jacobs IJ, Skates S, Davies AP, Woolas RP, JeyerajahA, Weidemann P, Sibley K, Oram DH. Risk of diagnosis ofovarian cancer after raised serum CA 125 concentration: aprospective cohort study. BMJ 1996; 313: 1355–1358.

2. Paramasivam S, Tripcony L, Crandon A, Quinn M,Hammond I, Marsden D, Proietto A, Davy M, Carter J, Nick-lin J, Perrin L, Obermair A. Prognostic importance of preop-erative CA-125 in International Federation of Gynaecologyand Obstetrics stage I epithelial ovarian cancer: an Australianmulticenter study. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 5938–5942.

3. Bast RC Jr, Klug TL, St John E, Jenison E, Niloff JM,Lazarus H, Berkowitz RS, Leavitt T, Griffiths CT, Parker L,Zurawski VR Jr, Knapp RC. A radioimmunoassay using a mon-oclonal antibody to monitor the course of epithelial ovariancancer. N Engl J Med 1983; 309: 883–887.

4. Bon GG, Kenemans P, Verstraeten R, van Kamp GJ, Hilgers J.Serum tumor marker immunoassays in gynecologic oncology:establishment of reference values. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;174: 107–114.

5. Gadducci A, Baicchi U, Marrai R, Ferdeghini M, Bianchi R,Facchini V. Preoperative evaluation of D-dimer and CA 125levels in differentiating benign from malignant ovarian masses.Gynecol Oncol 1996; 60: 197–202.

6. Predanic M, Vlahos N, Pennisi JA, Moukhtar M, Aleem FA.Color and pulsed Doppler sonography, gray-scale imaging, andserum CA 125 in the assessment of adnexal disease. ObstetGynecol 1996; 88: 283–288.

7. Valentin L. Use of morphology to characterize and managecommon adnexal masses. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol2004; 18: 71–89.

8. Timmerman D, Schwarzler P, Collins WP, Claerhout F,Coenen M, Amant F, Vergote I, Bourne TH. Subjective assess-ment of adnexal masses with the use of ultrasonography: ananalysis of interobserver variability and experience. UltrasoundObstet Gynecol 1999; 13: 11–16.

9. Valentin L. Prospective cross-validation of Doppler ultrasoundexamination and gray-scale ultrasound imaging for discrimina-tion of benign and malignant pelvic masses. Ultrasound ObstetGynecol 1999; 14: 273–283.

10. Valentin L, Hagen B, Tingulstad S, Eik-Nes S. Comparisonof ‘pattern recognition’ and logistic regression models fordiscrimination between benign and malignant pelvic masses: aprospective cross validation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001;18: 357–365.

11. Valentin L. Pattern recognition of pelvic masses by gray-scaleultrasound imaging: the contribution of Doppler ultrasound.Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1999; 14: 338–347.

12. Jacobs I, Oram D, Fairbanks J, Turner J, Frost C, GrudzinskasJG. A risk of malignancy index incorporating CA 125,ultrasound and menopausal status for the accurate preoperativediagnosis of ovarian cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1990; 97:922–929.

13. Timmerman D, Van Calster B, Jurkovic D, Valentin L, Testa A,Bernard J, Van Holsbeke C, Van Huffel S, Vergote I, Bourne T.Inclusion of CA-125 does not improve mathematical modelsdeveloped to distinguish between benign and malignant adnexaltumors. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 4194–4200.

14. Van Calster B, Timmerman D, Bourne T, Testa A, VanHolsbeke C, Domali E, Jurkovic D, Neven P, Van Huffel S,Valentin L. Discrimination between benign and malignantadnexal masses by specialist ultrasound examination versusserum CA-125. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99: 1706–1714.

15. Timmerman D, Testa AC, Bourne T, Ferrazzi E, Ameye L,Konstantinovic ML, Van Calster B, Collins WP, Vergote I, VanHuffel S, Valentin L. Logistic regression model to distinguishbetween the benign and malignant adnexal mass before surgery:a multicenter study by the International Ovarian TumorAnalysis Group. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 8794–8801.

16. Timmerman D, Valentin L, Bourne TH, Collins WP,Verrelst H, Vergote I. Terms, definitions and measurementsto describe the sonographic features of adnexal tumors: aconsensus opinion from the International Ovarian Tumor Anal-ysis (IOTA) Group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000; 16:500–505.

17. Kenemans P, van Kamp GJ, Oehr P, Verstraeten RA. Heterol-ogous double-determinant immunoradiometric assay CA 125II: reliable second-generation immunoassay for determining CA125 in serum. Clin Chem 1993; 39: 2509–2513.

18. Heintz AP, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Beller U, Benedet JL,Creasman WT, Ngan HY, Pecorelli S. Carcinoma of the ovary.Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003; 83: 135–166.

19. Newcombe RG. Improved confidence intervals for the differencebetween binomial proportions based on paired data. Stat Med1998; 17: 2635–2650.

20. Miettinen OS, Nurminen M. Comparative analysis of two rates.Stat Med 1985; 4: 213–226.

21. Valentin L, Ameye L, Jurkovic D, Metzger U, Lecuru F, VanHuffel S, Timmerman D. Which extrauterine pelvic masses aredifficult to correctly classify as benign or malignant on thebasis of ultrasound findings and is there a way of makinga correct diagnosis? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006; 27:438–444.

22. European Federation of Societies in Ultrasound in Medicineand Biology (EFSUMB). Minimum training recommendationsfor the practice of medical ultrasound. Ultrashall Med 2005;26: 79–105.

23. Bonfrer J, Baan A, Jansen E, Lentfer D, Kenemans P. Technicalevaluation of three second generation CA 125 assays. Eur J ClinChem Clin Biochem 1994; 32: 201–207.

24. Davelaar E, van Kamp G, Verstraeten R, Kenemans P. Compar-ison of seven immunoassays for the quantification of CA 125antigen in serum. Clin Chem 1998; 44: 1417–1422.

25. Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, Bertelsen K, Einhorn N,Sevelda P, Gore ME, Kaern J, Verrelst H, Sjovall K, Timmer-man D, Vandewalle J, Van Gramberen M, Trope CG. Prognos-tic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture instage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet 2001; 357:176–182.

26. Yazbek J, Raju SK, Ben-Nagi J, Holland TK, Hillaby K,Jurkovic D. Effect of quality of gynaecological ultrasonog-raphy on management of patients with suspected ovariancancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2008; 9:124–131.

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

354 Valentin et al.

27. Sladkevicius P, Jokubkiene L, Valentin L. Contribution ofthe morphological assessment of the vessel tree by three-dimensional ultrasound to a correct diagnosis of malignancyin adnexal masses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 30:874–882.

28. Testa AC, Timmerman D, Exacoustos C, Fruscella E, VanHolsbeke C, Bokor D, Arduini D, Scambia G, Ferrandina G.The role of CnTI-SonoVue in the diagnosis of ovarian masseswith papillary projections: a preliminary study. UltrasoundObstet Gynecol 2007; 29: 512–516.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION ON THE INTERNET

The following supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Diagnostic performance of pattern recognition and serum CA 125 depending on the confidence of theultrasound examiner in premenopausal patients

Table S2 Diagnostic performance of pattern recognition and serum CA 125 depending on the confidence of theultrasound examiner in postmenopausal patients

Table S3 Diagnostic performance when CA 125 is used as a second-stage test after ultrasound, i.e. requiring theresults of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate a benign diagnosis for a benign diagnosis to be made,in tumors considered to be certainly benign or certainly malignant by the ultrasound examiner

Table S4 Diagnostic performance when CA 125 is used as a second-stage test after ultrasound, i.e. requiring theresults of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate a benign diagnosis for a benign diagnosis to be made,in tumors considered to be probably benign or probably malignant by the ultrasound examiner

Table S5 Diagnostic performance when CA 125 is used as a second-stage test after ultrasound, i.e. requiring theresults of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate a benign diagnosis for a benign diagnosis to be made,in tumors where the ultrasound examiner was completely uncertain whether the tumor was benign or malignant

Table S6 Diagnostic performance when CA 125 is used as a second-stage test after ultrasound, i.e. requiring theresults of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate malignancy for a malignant diagnosis to be made, intumors considered certainly benign or certainly malignant by the ultrasound examiner

Table S7 Diagnostic performance when CA 125 is used as a second-stage test after ultrasound, i.e. requiring theresults of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate malignancy for a malignant diagnosis to be made, intumors considered probably benign or probably malignant by the ultrasound examiner

Table S8 Diagnostic performance when CA 125 is used as a second-stage test after ultrasound, i.e. requiring theresults of both pattern recognition and CA 125 to indicate malignancy for a malignant diagnosis to be made, intumors where the ultrasound examiner was completely uncertain whether the tumor was benign or malignant

Copyright 2009 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009; 34: 345–354.

Related Documents