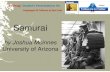

S AMURAI D IRECT 17 S AMURAI D IRECT The first ascent of the southeast face of Kamet in India. KAZUYA HIRAIDE AND KEI TANIGUCHI O ur plan to climb Kamet was not the result of any snap decision. We had faced many challenges before, and although confidence was born from these experiences, so too was fear and anxiety. At 7,756 meters, Kamet is the highest climbable mountain in the Garhwal region of India (since Nanda Devi is still off-limits). We’d collected many reports from other climbers and had studied photographs of the mountain, but we knew this research could not reveal Kamet’s true nature. Many climbers had been overwhelmed by the mountain, and it still had unexplored faces. Why? We could not know the answer until we had gone to have a look for ourselves, and no amount of knowledge would ease our anxiety until we had traversed the final ridge to the summit. Our partnership in the highest mountains began when we climbed a new route on the northwest side of Spantik (7,028 meters) in Pakistan in 2004. [Editor’s note: This line previously had been descended twice following climbs of other routes on Spantik.] After that climb, we decided to extend our trip and climb the north face of Laila Peak (6,096m), near the Gondogoro Gla- cier. Our desire for new challenges was honed by these experiences. The sharp peaks of ice and snow drew our eyes. The next year we climbed new lines on the east ridge of Muztagh Ata (7,546 meters) in China and the north face of Shivling (6,543 meters) in India, and on the latter both of us got severe frostbite. Kazuya lost four of his toes. Although we didn’t climb together for three years after the struggles on Shivling, each of us kept exploring. Kazuya climbed Broad Peak and Gasherbrum II. Kei climbed Manaslu and Everest. Those experiences made us smarter and more serious about our lives. A beautiful climb, we believe, must include coming back alive. Exploration of Kamet’s giant pyramid dates back to 1855, and it was first climbed in 1931 by a British expedition led by Frank Smythe, via the Purbi (East) Kamet Glacier, Meade’s Col, and the northeast ridge. It was then the highest mountain ever summited. Most ascents since have followed the same route, giving many climbers a good look at the 1,800-meter southeast face, which rises from the head of the Purbi Kamet Glacier. In 2005 the mountain was reopened to foreigners after having been off-limits for decades. Americans John Varco and Sue Nott hoped to try the southeast face in 2005, but poor weather kept them from even setting foot on the route—they hardly even saw it. We wanted to maximize our chances to reach the summit. We did not want anyone to say, “What is your big excuse? You could not climb because of the bad weather?” We didn’t have enough money to contract a company that provides weather forecasting in the Himalaya, so after establishing our base camp (4,700 meters) at the confluence of the Raikana and the Purbi Kamet glaciers on September 1, we called friends in Japan every few days by satellite phone to Acclimatizing at Camp 1 alongside the Purbi Kamet Glacier, with the southeast face of Kamet in the distance. The 1,800m line of Samurai Direct follows the obvious sinuous couloir in the center of the face. The normal route to Kamet’s 7,756m summit generally follows the right skyline. Kazuya Hiraide

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

SA M U R A I DI R E C T 17

SA M U R A I DI R E C TThe first ascent of the southeast face of Kamet in India.

KAZUYA HIRAIDE AND KEI TANIGUCHI

Our plan to climb Kamet was not the result of any snap decision. We had faced manychallenges before, and although confidence was born from these experiences, so too wasfear and anxiety. At 7,756 meters, Kamet is the highest climbable mountain in the

Garhwal region of India (since Nanda Devi is still off-limits). We’d collected many reports fromother climbers and had studied photographs of the mountain, but we knew this research couldnot reveal Kamet’s true nature. Many climbers had been overwhelmed by the mountain, and itstill had unexplored faces. Why? We could not know the answer until we had gone to have a lookfor ourselves, and no amount of knowledge would ease our anxiety until we had traversed thefinal ridge to the summit.

Our partnership in the highest mountains began when we climbed a new route on thenorthwest side of Spantik (7,028 meters) in Pakistan in 2004. [Editor’s note: This line previouslyhad been descended twice following climbs of other routes on Spantik.]After that climb, we decidedto extend our trip and climb the north face of Laila Peak (6,096m), near the Gondogoro Gla-cier. Our desire for new challenges was honed by these experiences. The sharp peaks of ice andsnow drew our eyes.

The next year we climbed new lines on the east ridge of Muztagh Ata (7,546 meters) inChina and the north face of Shivling (6,543 meters) in India, and on the latter both of us gotsevere frostbite. Kazuya lost four of his toes. Although we didn’t climb together for three yearsafter the struggles on Shivling, each of us kept exploring. Kazuya climbed Broad Peak andGasherbrum II. Kei climbed Manaslu and Everest. Those experiences made us smarter andmore serious about our lives. A beautiful climb, we believe, must include coming back alive.

Exploration of Kamet’s giant pyramid dates back to 1855, and it was first climbed in 1931by a British expedition led by Frank Smythe, via the Purbi (East) Kamet Glacier, Meade’s Col,and the northeast ridge. It was then the highest mountain ever summited. Most ascents sincehave followed the same route, giving many climbers a good look at the 1,800-meter southeastface, which rises from the head of the Purbi Kamet Glacier. In 2005 the mountain was reopenedto foreigners after having been off-limits for decades. Americans John Varco and Sue Notthoped to try the southeast face in 2005, but poor weather kept them from even setting foot onthe route—they hardly even saw it.

We wanted to maximize our chances to reach the summit. We did not want anyone to say,“What is your big excuse? You could not climb because of the bad weather?” We didn’t haveenough money to contract a company that provides weather forecasting in the Himalaya, soafter establishing our base camp (4,700 meters) at the confluence of the Raikana and the PurbiKamet glaciers on September 1, we called friends in Japan every few days by satellite phone to

Acclimatizing at Camp 1 alongside the Purbi Kamet Glacier, with the southeast face of Kamet in the distance. The1,800m line of Samurai Direct follows the obvious sinuous couloir in the center of the face. The normal route toKamet’s 7,756m summit generally follows the right skyline. Kazuya Hiraide

SA M U R A I DI R E C TTH E AM E R I C A N AL P I N E JO U R NA L, 2009 1918

check the forecast for Joshimath, the closest town. But we soon learned that the forecast forJoshimath had little to do with what was happening on Kamet. When the forecast said Joshi-math would have rain, Kamet would have blue sky.

Instead, we watched the clouds over Kamet, and soon we discovered a common denom-inator for good weather: the wind direction. When the winds blew from the southwest, Kamethad mild weather; a strong south wind would clear the sky over the peak. When the windreversed, the weather always deteriorated and heavy rain or snow began. These were big lessonsfor us.

We acclimatized in two stages. From September 4 to 7, we made a round-trip to the footof the face at 5,750 meters, with two camps on the Purbi Kamet Glacier, and we found that theavalanche danger did not appear too serious in the main couloir on the wall. After two rest daysin base camp, we climbed the normal route to 7,200 meters, above Meade’s Col, to acclimatizeand explore the descent route. We camped at 6,600 meters for two nights to study the face,focusing on three main concerns: the three obvious cruxes on the route, the possibility of ava-lanche danger from the serac at the top, and the places where we would bivy. We left a cache offood and fuel at 6,600 meters for our descent and returned to base camp on the 16th.

For the next week, as heavy snow fell, we discussed the food and equipment that wewould carry on the wall. We decided to bring a foam mat cut in two and a 600-gram, three-quarter-length sleeping bag that we would share. A small Gore-Tex tent. Two 50-meter, 7.5mmropes. And a small rack, mostly ice screws.

Kazuya Hiraide (left) and Kei Taniguchi leaving base camp for acclimatization on the normal route. The two climbedto 7,200m and left a food and fuel cache at 6,600m. Kei Taniguchi Collection

Hiraide leads steep ice on the first crux section of the southeast face, at ca 6,700m. Each afternoon, spindrift wouldpour down the face as the sun warmed the upper wall. Kei Taniguchi

We knew that lighter weightwould be one key to success, but wealso wanted to make sure we hadenough food. We had not forgottenthe lesson from Shivling, and now,with more experience under ourbelts, we focused on the balance ofnutrition and calorie intake per day.Our motto was “sleep well and eatwell, and the next day we can climbwithout fatigue.” We packed food forfive days plus some emergency food.In the end, it took us six days to climbthe wall instead of our planned fourdays. But because of the extra food,we were not nervous about the delay.

During our preparation, weargued endlessly about what tobring—it was a long process. Howev-er, that process made us more confi-dent in our gear, and the result wasnearly perfect.

The bad weather at base camplasted more than a week. When wehad almost given up hope, the windchanged and good weather came back.We started toward the wall on Sep-tember 26 in soft, deep snow. Therewas one meter of new snow at Camp 1and 1.5 meters of snow at Camp 2. Ittook twice as long to reach the wall asit had before. We had to dig out ourhalf-destroyed tent at Camp 2, but itwas still usable. We establishedadvanced base camp at 5,900 meters,at the foot of the face, on September28. The line was obvious, following a

sinuous couloir directly to the top: perfect and beautiful. We no longer had any doubts.In the morning the sky was bright and clear. The climbing was not very difficult, and we

only belayed toward the end of the day. At 6,600 meters, below the obvious first crux section,we spent an hour and a half chopping into the ice to make a small shelf. On this wall, we wouldnever find a comfortable place for two people to sleep, but we are small and we only had a sin-gle half sleeping bag, so small ledges were enough. First we lay down both facing to the right,and after two hours we turned over and faced the opposite direction. That night was freezing,under millions of stars.

SA M U R A I DI R E C TTH E AM E R I C A N AL P I N E JO U R NA L, 2009 2120

The first steep crux hadrotten ice and loose rock coveredby dry snow. In the afternoon,spindrift avalanches poureddown the face, blinding us andmaking for freezing belays. Theeffort of climbing did not stopour bodies from shaking withcold. At 6,750 meters, we founda small snow ridge where wechopped out a tent site that wasa little better than the last one.During the night, our tent waspelted with small avalanchesand stones.

Our reconnaissance had usworried about the next crux, butthe truth was way beyond ourexpectations. Loose rock androtten ice were everywhere. Afterchopping away 30 centimeters ofbad ice, we’d find black iceunderneath. It was difficult tofind the way, and at nearly 7,000meters it was hard to breathe.Negative thoughts passedthrough our minds: Why do weclimb? What is the meaning ofso much sacrifice? At the end ofthe day, we were only halfway upthe steep wall. We made a tension traverse to a small snowfield under an overhang and set up abivy at 7,000 meters, cutting ice as usual. By the time we crawled into the refuge of our little tentit was past midnight.

The next day was short. Two more pitches saw us to the end of the second crux passage,and then two and a half pitches of steep snow brought us to the base of the third crux. It lookedbigger than we had expected. Exhausted from the previous night’s brief sleep, we didn’t havethe time or energy to start up this wall, so we cut a ledge and set up the tent at 3 p.m. We knewwe were moving slowly on the face, but we were confident in the weather. We could not stopshivering, though, and at night we massaged each other’s feet. Kazuya was very worried abouthis toes and asked for an injection of Lovenox to improve his blood flow.

“Where should I inject it?”“Anywhere!”He didn’t want to lose more toes.On the fifth morning of the climb, we traversed to the base of the third steep wall. The

first pitch was mixed, followed by three and a half pitches of hard alpine ice. Finally we entered

Hiraide begins the second crux, a six-pitch wall at ca 7,000m thatrequired parts of two days to climb. Kei Taniguchi

Taniguchi heads toward vertical ice in the first crux section of theroute. Sun-warmed, rotten ice made for delicate and time-con-suming climbing. Kazuya Hiraide

Hiraide traversing to the base of the third crux passage on the southeastface, another steep mixed section at ca 7,200m. Kei Taniguchi

SA M U R A I DI R E C T 23

That snow couloir seemed endless, however, and we moved so slowly. We could see thesummit ridge, but it never seemed to get any closer.

“I’m dying, I’m dying,” Kei muttered, and Kazuya responded, “Don’t worry, you’re notdying.”

Then he asked, “Do you want to go down?”“No, no,” she said. “Let’s go up.”We bivied in a crevasse just 150 meters below the summit. We could see the top, but we

did not have the energy to continue. There wasn’t much food left, but we didn’t have anyappetite anyway.

On the morning of October 5, the seventh day of the climb—10 days out from basecamp—the eastern horizon was flooded with gorgeous orange light as the sun rose from behindthe right flank of Mt. Kailash. We traversed over the ridge above our bivy onto the upper north-east face, and by 10 a.m., after an hour of snow climbing, we were on top. The weather was clear,and we enjoyed a majestic 360-degree view, with the curve of the Earth visible at the horizon—a view entirely different from what we’d been able to see during the climb. We reveled in ournew perspective.

SUMMARY:

AREA: Central Garhwal, India

ASCENT: Alpine-style first ascent of the southeast face of Kamet (7,756m), by the routeSamurai Direct (1,800m, WI5+ M5+), Kazuya Hiraide and Kei Taniguchi. Leaving basecamp on September 26, the two Japanese walked three days up the Purbi Kamet Glacierto advanced base camp at 5,900m, and then climbed the face with six bivouacs, summit-ing October 5, 2008. They descended the northeast face (the 1931 first-ascent route) to afood and fuel cache they had left at 6,600m, and the next day they continued down toCamp 2 on the glacier. They reached base camp before dawn on October 8, nearly 13 daysafter leaving, after walking through the night.

A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Kazuya Hiraide, 29, works in the ICI Sports shop inTokyo. Kei Taniguchi, 36, also lives in Tokyo, whereshe works as a facilitator for corporate team-building.

Translated by Yoko Omuro, with assistance fromLeif Faber.

Taniguchi and Hiraide at Kamet’s summit. Their luckwith the weather ended during the descent, and ittook them nearly three full days to reach base camp.Kazuya Hiraide

TH E AM E R I C A N AL P I N E JO U R NA L, 200922

the Banana Couloir, the snow gully leading to the top, at about 7,250 meters. The scenery fromthis elevation was stupendous—words cannot express it—but even though the world was beau-tiful our bodies felt ugly. We could barely speak, but we encouraged ourselves by saying, “Thesummit is tomorrow!”

Taniguchi climbing the Banana Couloir at ca 7,250m, above the Purbi Kamet Glacier, at the end of the fifth dayon the route. Only 500m of snow climbing remained, but the exhausted climbers needed two more bivouacs toreach the summit. Kazuya Hiraide

Related Documents