Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

A People's Agenda?Post - Tsunami Aid in Aceh

February 2006

Cover by Fahmi

We are grateful for the financial support of

Trocaire Kerkinactie ICCO

EYE ON ACEH

AIDWATCH

in consultation with

:Acknowledgements

The list of those to whom we are greatly indebted, and without whose generosity of time this report would not havebeen possible, is indeed long: a very special 'thank you' to the local government officials in Aceh who gave not onlyinformation and insight, but also their on- and off-the-record opinions.

We are also grateful to the staff of the donors for whom policies of transparency translate into practice: the WorldBank, both in Jakarta and Aceh; the staff of the Multi Donor Trust Fund; the ADB, and the delegation of the EuropeanCommission, all were most helpful. In addition, to the many local and international NGOs whose staff spent time toexplain projects, share data, and occasionally even give an 'insider's' overview of programmes - thank you.

Many thanks also to friends who gave advice during the long process of researching and writing this document, andthe reviewers whose candid and insightful comments were invaluable. We are also grateful to the patience andassistance of friends in both the Eye on Aceh offices, and to our network in Brussels. There is one friend who joinedthe team in the closing months of this project whose intellect and co-authorship has been invaluable: to WynneRussell, many thanks.

And finally, to the Acehnese people - the victims of the tsunami - whose lives were ripped apart that day on 26December 2004, and whose surreal existence forms the basis of this report: our gratitude, our admiration, and oursolidarity lies with these courageous people.

Eye on Aceh Research Team: Dhoni, Firman, Jenny, Muhib, Safril, Samsul, Sofia, and Zakaria.

:Executive Summary

This assessment gives voice to the responses of ordinary Acehnese - men and women - to some of the completedand ongoing rehabilitation and reconstruction programmes being conducted in post-tsunami Aceh. We werecurious to know how individuals and communities in Aceh had been affected by their experience of the relief,reconstruction and development assistance programmes that have been mounted in the province since thedisastrous events of 26 December 2004. In the course of our research, we asked Acehnese communities andindividuals: Were they satisfied with the way that such assistance programmes had been carried out in theircommunity? Were they consulted at the needs assessment, concept, or design stages of the programme? If so, towhat extent? What measures were taken to ensure that all community members - including women, whotraditionally have been marginalised in the Acehnese decision making process - were consulted? Were people keptabreast of developments as the project progressed through various stages of planning and implementation? Howrelevant and useful were the projects? Had there been a transfer of skills to local people during the planning orexecution of the project? What had been the impact of the aid on local communities or individuals? And how couldaid have been delivered more effectively?

Our research identified four main areas of concern. The first of these was consultation and communication withbeneficiaries. All too frequently, we heard that Acehnese beneficiaries feel excluded from the rehabilitation andreconstruction process, reduced to the status of passive observers while others lay the foundations for their future.People often spoke of the anxiety they felt in the face of unexplained delays, and of their frustration when easilyavoidable mistakes - design flaws in houses or boats, for instance - rendered assistance ineffective orinappropriate. Rather than a seamless transition from relief to rehabilitation and then to development (the LRRDprinciple), for many local people there was a disconnect between what was needed for recovery and rehabilitationand what was delivered. We found that many of the concerns raised might have been avoided had donors andimplementers placed more emphasis on consultations with communities, including women, as part of pre-planningneed-assessment exercises, project design, and project implementation; ensured that recipients were kept up todate on developments in projects; and capitalised on local expertise. In this context, we were troubled by thecurrent emphasis on "socialisation," which suggests a one-way flow of information after plans are in place, ratherthan on genuine and equal two-way communication.

The second area of concern related to the impact of projects on Aceh's social fabric. Reconstruction aid to Acehhas all too frequently come at a social cost. Unequal levels of assistance, whether within or between communitiesor regions, and the ability of some individuals to profit from the presence of international agencies while others bearthe brunt of inflation, are already fuelling social jealousy. Meanwhile, the potential for tension between thosedisplaced by the tsunami and the communities into which many have settled will only grow as more people migratefrom 'non-tsunami-affected' regions into 'tsunami-affected' ones in search of employment and assistance. As thedivide between winners and losers in the reconstruction aid stakes grows, and social capital is steadily eroded, thechances increase for social conflict. Indeed, despite increasing attention in the international developmentassistance community to the relationship between development assistance and conflict, many of the programmesexamined in this study appeared to lack a conflict-sensitive perspective. Meanwhile, the marginalization of womenin decision-making processes reinforces existing patterns of gender discrimination.

The third area of concern was the way in which donors and implementers handled the project cycle. In particular,we were surprised by the lack of donor and implementer monitoring of projects, which might have identified ongoingproblems, and of post-project evaluation, which might not only have identified issues of concern but might alsohave led to a crackdown on incompetent or corrupt partners. We also were alarmed to find that donors andimplementers frequently ignored the recommendations of internal and external evaluations of broader agencystrategies.

The final area of concern was that of sustainability. Donors and implementers often appeared more focused ontheir own short-term need for visible results than on the longer-term needs of the local population. We wereconcerned that in the rush to spend money, not only were donors and implementing agencies too busy to activelybuild the local capacity that will be vital if ambitious programmes are to be sustained after outside actors leave, butsome programmes' partnerships actually lowered capacity and morale in some local groups. We further identifiedan alarming level of ongoing environmental damage related to reconstruction efforts, in particular deforestationresulting from illegal logging, which not only threatens the province's biodiversity and potential for economicactivities such as ecotourism but has the potential to lead to yet more natural disasters such as the flooding andmudslides that killed around 20 people and displaced thousands more in 2005.

Taken together, these areas of concern appear to have contributed to a number of worrying outcomes. First, manybeneficiaries have been left feeling powerless and frustrated, adding stress to an already traumatised population.Second, persistence in inappropriate or ineffective programmes has led to substantial waste, both of money andmaterial and of good will. Third, disparities in reconstruction assistance between individuals, communities andregions runs the risk of creating new social divisions as well as of exacerbating existing ones. Finally, the study'sfindings raise serious questions about whether Aceh's social or physical environment will be able to stand up to theshort-and long-term effects of many aspects of the reconstruction effort.

1

In light of these findings, we offer 20 recommendations, grouped into five general categories:

Communication and consultation with local communitiesImprove community consultation at all stages of project implementation.Improve communication with communities.Increase community participation in project implementation.Increase women's participation in community consultation, communication, and implementation.Increase involvement of civil society organisations.Be sensitive to broader community priorities when initiating projects.

Building local capacityStrengthen cooperation and collaboration with local government.Take steps to prevent brain drain from the civil service.Work to increase the capacity of local NGOs using a needs based agenda.

Avoiding social conflictBe sensitive to potential conflicts between locals and outsiders.Reduce the aid gap between 'tsunami-affected' and 'non-tsunami-affected' areas.Defuse social jealousy emerging around the issue of different types of housing.Ensure cash-for-work schemes do not widen the poverty gap, or cause social jealousy.Prioritise efforts to address the policy gap vis- -vis ex-renters and the landless for rehousing.Avoid individualistic approaches that erode traditional communal forms.Integrate a conflict management perspective into all programmes.

Protecting the environmentTake tough steps to reduce the use of illegally logged timber and to ensure that other construction materials comefrom environmentally sound and legal sources.

Monitoring and evaluationRestructure the project and programme evaluation processes to include beneficiaries.Engage in more monitoring of local partners.Be responsive to changes in conditions and needs.

••••••

•••

•••••••

•

•••

ィ

AcronymsI. Introduction

The assessment- Methodology

II. Aceh and the tsunamiA devastating earthquake and tsunamiHumanitarian response: the emergency phaseShifting from relief to reconstruction

- Bureaucratic delays: the dilemma of on-budget mechanisms- Reconstruction efforts assisted by new peace agreement

III. A people's reconstruction agenda?The reconstruction process

- Difficult problems, difficult choicesConsultation and communication

- Consultation during pre-project needs assessments- Consultation during project design- Social accountability to beneficiaries- All-inclusive consultation and communication- Disconnects between priorities

Social impact- Inequalities and the potential for conflict in post-tsunami Aceh

Civil society and local government- Building capacity- Under-valuing local government, overstretching NGOs- Local or Indonesian NGOs- Brain drain from the civil service

Corruption, collusion and nepotism (KKN)

The environmental cost of reconstructing Aceh- Deforestation- Laundering illegal timber in North Aceh

Donor and implementer 'best practice’- Coordination between donors

- Monitoring and evaluation- Reacting to evaluations and changing conditions

IV. Conclusion

V. Recommendations

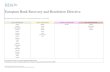

Appendix 1 - Donors at GlanceMulti Donor Trust FundAsian Development BankGovernment of AustraliaEuropean CommissionWorld Bank

Notes

Case Study UNICEF children centres

Case Study ACTED'S 'aid' boats

Case Study Going it alone is risky: the case of the Queensland government

Case Study TGH aid boats - still afloat

Case Study The MDTF's shelter programme

Case Study AIPRD support for sub - district and village government

:Table of Contents

1

33

56677

9999

10121315181919232424252526262728282931323233343536

37

39

424243444546

47

A PEOPLE'S AGENDA? POST-TSUNAMI RECONSTRUCTION AID IN ACEH

1

:Acronyms

ACTED

ADBAIPRD

AIROALGAP

AMM

ASEANATFAusAID

BAPPENAS

BRR

BRRD

CARDI

CBOCCSC

CDACDDCFWCGICHFCoHACRSCWSHP

DECDIPA

DPR-RI

DPRD I

DPRD II

ECECHO

ESPNAD

ETESP

EUFAOFFIGAAGAM

GDPGTZ

ARF

BAKORNAS PBP

BPK

BPN

IAIN

Agency for Cooperation and TechnicalDevelopmentAsian Development BankAustralia - Indonesia Partnership forReconstruction and DevelopmentAustin International Rescue OperationAceh Local Governance ActionProgrammeAceh Monitoring MissionAceh Recovery ForumAssociation of South East Asian NationsAsian Tsunami FundAustralian Agency for InternationalDevelopmentNational Coordinating Agency for IDPand Disaster Management

National Development Planning AgencySupreme Audit Institution

National Land Agency

Reconstruction and RehabilitationAgency

Village Reconstruction andRehabilitation Agency

Consortium for Assistance andRecovery towards Development inIndonesiaCommunity-Based OrganisationCommunity-Construction SupportCentresCommunity-Driven AdjudicationCommunity-Driven DevelopmentCash-for-workConsultative Group for IndonesiaCommunity Habitat FinanceThe Cessation of Hostilities AgreementCatholic Relief ServicesCommunity Water Services and HealthProjectDisaster Emergency CommitteeBudget Implementation Lists

People's Representative Council _ theRepublic of Indonesia

Local parliament at provincial level

Local parliament at district level

European CommissionEuropean Commission HumanitarianOfficeEmployment Service for the People ofNanggroe Aceh Darussalam ProvinceEarthquake and Tsunami EmergencySupport ProjectEuropean UnionFood and Agriculture OrganizationFauna and Flora InternationalGerman Agro ActionFree Aceh Movement

Gross Domestic ProductGerman Technical Cooperation AgencyState Islamic Institute

(BadanKoordinasi Nasional untuk PenangananBencana dan Pengungsi)

(Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan)

(Badan Pertanahan Nasional)

(Badan Rehabilitasi danRekonstruksi)

(BadanRehabilitasi dan Rekonstruksi Desa)

(Daftar Isian Proyek Anggaran)

(DewanPerwakilan Rakyat _ Republik Indonesia)

(Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah I)

(Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah II)

(Gerakan Aceh Merdeka)

(Instilute Agama Islam Negeri)

ICASERD

ICMC

IDPIFRC

ILOINGO

IOMIRCJFPRJRSKDPKKN

KKTGA

KPK

KPKN

LBHLRRD

MDTF (ANS)

MoUMSEMSFNADNGONRCOBIPAPAN

PEFPPK

PT

RALAS

RpRSUZA

SAK

SATKORLAK PBP

SATLAK PBP

SKSHH

TGHTNI

UKUNUNDP

Indonesian Center for Agro-Socio-Economic Research and DevelopmentInternational Catholic MigrationCommissionInternally Displaced PersonInternational Federation of Red Crossand Red Crescent SocietiesInternational Labor OrganizationInternational Non-GovernmentalOrganisationInternational Organization for MigrationInternational Rescue CommitteeJapan Fund for Poverty ReductionJesuit Refugee ServiceKecematan Development ProjectCorruption, collusion and nepotism

Task Force for Gender Transformationin Aceh

Corruption Eradication Committee

Office of Treasury and State Treasury

Legal Aid FoundationLinking Relief, Rehabilitation andDevelopmentMulti Donor Trust Fund(for Aceh and North Sumatra)Memorandum of UnderstandingMicro and Small EnterpriseMedecins sans FrontieresNanggroe Aceh DarussalamNon-Governmental OrganisationNorwegian Refugee Council

Defender for Farmers and FishermenFoundation

Poverty and Environment FundProgramme Pengembangan Kecametan

Limited Corporation

Reconstruction of Aceh LandAdministration SystemIndonesian RupiahZainal Abidin General Hospital

Corruption Eradication Unit

Coordinating and ImplementationAgency for IDPs and DisasterManagement

Implementation Agency for IDPs andDisaster Management

Legal Certificate of Forest Product

Triangle Generation HumanitaireIndonesian Armed Forces

United KingdomUnited NationsUnited Nations Development Programme

(Korupsi, Kolusi dan Nepotisme)

(Kelompok Kerja TransformasiGender Aceh)

(Kornisi Anti Korupsi)

(Kantor Perbendaharaan dan KasNegara)

Obor Berkat Indonesia

(Yayasan Pembela Petanidan Nelayan)

(Kecamatan Development Project)

(Perseroan Terbatas)

(Rumah Sakit Umum Zainal Abidin)

(Satuan Anti Korupsi)

(Satuan KoordinasiPelaksana untuk Penanganan Bencanadan Pengunusi)

(SatuanPelaksana untuk Penanganan bencanadan Pengungsi)

(Surat Ketetangan Sahnya Hasil Hutan)

(Tentara Nasional Indonesia)

A PEOPLE'S AGENDA? POST-TSUNAMI RECONSTRUCTION AID IN ACEH

2

UNFPAUNICEFUN-OCHA

UNSYIAH

UPPUKUSUUPA

WALHI

WB

United Nations Population FundUnited Nations Children's FundUnited Nations Office for theCoordination of Humanitarian AffairsSyiah Kuala University

Urban Poverty ProgrammeUnited KingdomUnited StatesIndonesian Agrarian Laws

Indonesia's Friends of the Earth

World Bank

(Universitas Syiah Kuala)

(Undang-Undang Pokok Agraria)

(Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia)

AdatBahasa IndonesiaBarakBupatiCamatDesaDinas

DusunGeuchikGotong Royong

Kabupaten

Kecamatan

MadrasahMeunasahPanglongPolsekPoskoProvinsi

TambakWalikotaWarung kopiYayasan

Customary lawThe language of IndonesiaTemporary shelterDistrict headSub-district headVillageLocal government department of lineministriesSub-villageVillage chiefCommunity joint works for communitypurposesGovernment administration at districtlevelGovernment administration at sub-district levelIslamic educational institutionCommunity/village hallShop where people buy processed woodSub-district police officeTemporary Coordination CentreGovernment administration at provinciallevelShrimp/fish pondsMunicipal headCoffee stallsFoundation

:Glossary of Terms

The assessment

This assessment gives voice to the responses ofordinary Acehnese - men and women - to some of thecompleted and ongoing rehabilitation and reconstructionprogrammes being conducted in post-tsunami Aceh.We were curious to know how individuals andcommunities in Aceh had been affected by theirexperience of the relief, reconstruction anddevelopment assistance programmes that have beenmounted in the province since the disastrous events of26 December 2004. In this respect, we were interestednot just in the degree to which various programmes hadmet quantitative targets, but to what extent ordinaryAcehnese felt that reconstruction programmes hadbeen sensitive to, and in fact met, what they identifiedas their needs. In this context, we were interested bothin how donors and implementers had includedcommunities in project conceptualisation, design andexecution and in how they monitored the success oftheir projects. This study does not purport to be anoverview of the entire relief, rehabilitation orreconstruction process in Aceh. Rather, using a seriesof case studies from the activities of five major donors,mainly from the rehabilitation and reconstruction phase,we identify common trends that were also visible inmany other projects and aspects of broaderreconstruction efforts.

There is no doubt that international assistance was vitalto the relief effort in Aceh, providing food, water, shelterand medical care for hundreds of thousands of tsunamivictims. In moving from relief to rehabilitation, and finallyto the reconstruction and development phases, theinternational community, and in particular the fivedonors on whose projects this study primarily draws,have made enormous contributions. This report doesnot seek to denigrate this very positive and necessarywork. Rather, it seeks to make a constructivecontribution towards identifying ways in which pastmistakes might be avoided in the future and ongoingprojects might be improved.

Most projects had some things go right and some thingsgo wrong. In presenting a few detailed stories that arescattered throughout the report, the intention is not toissue individual praise or indictments, but to providefully contextualised examples of themes that emergedin many projects. These case studies are presented toshow how the positive or negative dynamics from oneaction or issue can spill over to the larger projectenvironment, affecting mechanisms and creating resultsthat may linger in the community long after the donor isgone. Ideally, these lasting impacts would be positive,but in many cases they tend to be more negative.

Between March and December 2005 we visited over ahundred communities and looked at almost 50 projectsacross five major areas - emergency aid, health,housing, livelihoods, and infrastructure - funded by fivemajor donors. We conducted individual and focus groupinterviews, meetings, and briefings, as well as directobservation; we also conducted random questionnaire-style interviews in communities. To hear the other sideof the story, we also collected print information from andtalked to donors and implementers.

2

Methodology

I. Introduction The research was carried out by a team of sixAcehnese researchers, one Indonesian researcher inJakarta, and researchers in Australia and in Brussels. Intotal, we collected information from over 120 Indonesianand international government and non-governmentorganisations, intergovernmental organisations, andinternational financial institutions; in the process, wespoke to about 1,000 individuals.

The donors from whose programmes the bulk of thecase studies and examples are drawn are the AsianDevelopment Bank (ADB), the World Bank, Australiangovernment assistance, primarily through the newAustralia-Indonesia Partnership for Reconstruction andDevelopment (AIPRD), the European Commission (EC),and the Multi Donor Trust Fund for Aceh and NorthSumatra (MDTFANS, hereafter MDTF). Some of thesedonors, such as the ADB and World Bank, work closelywith the Indonesian government and channel themajority of their funding on-budget via the IndonesianMinistry of Finance. This has led to delays in disbursingfunds; in fact most of the ADB's programmes plannedfor the first year have been delayed until 2006. Bothdonors have expanded existing programmes, andestablished new ones to assist in reconstruction efforts.The ADB and World Bank are involved in the medium tolong-term reconstruction and rehabilitation process,contributing not only money, but much-needed technicalassistance to Indonesian government departments andmechanisms. In contrast, the AIPRD usuallyimplements programmes via managing contractors,using these companies to disburse funds directly to theproject in the field. Their rationale for this approach isthat it partly allows for quicker implementation ofprogrammes. Similarly, the European Community'sHumanitarian Aid department (ECHO) responds toemergency situations via a system of long-standingpartner organisations. Its funds can be disbursed swiftlyand off-budget; although primarily emergency focused,ECHO can continue to fund secondary emergencies forseveral years in one disaster zone. Meanwhile, theEuropean Commission has put its reconstruction faith inthe MDTF, committing all its longer-term rehabilitationand reconstruction assistance to the Trust Fund tomanage. As the single largest donor to the Trust Fund,the EC is the co-chair and is able to have substantialpolicy input into both on and off-budget grants from thefund. The MDTF itself was established by theIndonesian government and the World Bank; its 15members have contributed more than $530 million. TheFund was initially established to support large-scale on-budget programmes using Indonesian governmentmechanisms, but more recently has turned to somedirect (off-budget) funding to partner organisations.Together, these donors represent a variety ofmechanisms for channelling assistance; even thoughnot all are among the largest donors to the Acehnesereconstruction effort, their programme variety in termsof substance and mechanisms make them of interest.

The initial problems faced by the research team werethose relating to identifying who in a particular agencyor donor was responsible for specific programmes, andwho had the information that was required for ourresearch. We were conscious of the drain on alreadyoverstretched human resources of many donors andimplementers, and were careful to consider time andother constraints. For the most part, staff from theprimary donors were extremely accommodating with

3

3

their time and forthcoming with Information. The MDTFand the World Bank operated an almost 'open door'policy with our team; the ADB and EuropeanCommission delegations were also very helpful. Theexception was the AIPRD and its parent agencyAusAID; despite several attempts by phone, e-mail,and even personal visits to the offices in Aceh, requeststo meet senior members of staff were refused. We weretold on several occasions that a dedicated member ofstaff in Canberra, Australia was the only person with theauthority to provide information on the reconstructionprocess; this person, however, was uncontactable byphone or e-mail. For this reason, the analysis ofAustralian programmes is almost wholly informed by ouron-the-ground research, with minimal input from

4

members of the Australian government's publicrelations staff in Jakarta and some junior staff in Aceh.Meanwhile, we met with varying degrees of helpfulnessfrom implementers, ranging from a high level oftransparency to a refusal to speak with us; many werereluctant to speak about project specifics such asbudgets and such basic information as the exactlocation of a project and who implementing partnerswere. There was particular sensitivity when theimplementing partner was a local non-governmentalorganisation (NGO) or community-based organisation.The research team was often left with the impressionthat site visits and in-depth discussions with staffmembers were most unwelcome.

Before the tsunami, Aceh was, in the Indonesiancontext, a relatively wealthy province in terms ofresources availability. Most people lived in their ownhomes and had access to land. Economic activity wasfocused largely around traditional farming and fishing,as well as forestry with 47% of Aceh's workforceengaged in these sectors. Many others were smalltraders or civil servants or worked in the service sector.Nevertheless, this is not to say there was no poverty inAceh: violent conflict in the province had all butdestroyed Aceh's economy. Government data showsthat in September 2004, 53.3% of families in Aceh wereliving below the poverty line.

At the time when the tsunami swept ashore, a bloodywar of independence had been raging in the provincefor almost 30 years, leading to an estimated 15,000deaths. Many thousands more were tortured orimprisoned, or simply disappeared. The social andeconomic fabric of Aceh's society was considerablyweakened, leav ing many communi t ies wi thimpoverished social services and economies that hadlong ceased to function. After years of escalatingviolence, a peace process began in 2000 that producedweak agreements aimed at stemming the violence;unfortunately, none were long-lived. Finally, inDecember 2002, the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement(CoHA) was signed between the Indonesiangovernment and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM).Many were hopeful that the CoHA could in fact bringpeace to the troubled province, but several monthslater, amid escalating violence in the field and anincreasingly hardline stance from some members of theIndonesian government and the armed forces (TNI),further peace negotiations were cancelled and waragainst the separatists was declared. The CoHAcollapsed on 18 May 2003, and martial law wasimposed in Aceh one day later. The GAM peacenegotiators were arrested, charged with treason andimprisoned. Several weeks later, Aceh was effectivelyclosed to the outside world, and local media was tightlycontrolled as the Indonesian military embarked on asearch-and-destroy mission to "crush" GAM and itssupporters. Finally, after a violent and bloody year ofmartial law in which 2,000 people (largely civilians) werekilled, the security situation was downgraded to a stateof civil emergency. But the estimated 40,000 militaryand police that had been stationed in the provinceduring martial law to fight GAM remained, and were infact instrumental in saving lives in the hours and daysafter the earthquake and tsunami of December 2004.

At 8 am on 26 December 2004, an earthquakemeasuring 9.0 on the Richter scale occurred in theIndian Ocean. Its epicenter was just 150 kilometresfrom Indonesia's most northwestern province of Aceh.Less than an hour later, a tsunami reached the shoresof Aceh and the North Sumatran island of Nias, itswaters reaching as far inland as seven kilometres insome places. Similar waves also struck over a dozenother countries in Southeast Asia, South Asia and EastAfrica.

The damage inflicted by the tsunami that hit Acehshocked even the most experienced disaster specialist.

4

5

A devastating earthquake and tsunami

5

Seemingly sturdy structures were razed; ships wereripped from their moorings and came to rest on top ofbuildings; thousands of dead bodies lay scattered. Inthe area worst affected, the administrative district ofAceh Jaya, 85% of buildings were damaged, while theprovince's capital of Banda Aceh sustained 75%damage. Thirteen of Aceh's twenty-one administrativedistricts were affected by the tsunami, six of themseverely. The coastline was redrawn, with land both lostto and gained from the sea. The damage toinfrastructure was massive: communications werewiped out, fuel depots destroyed, drinking watersupplies contaminated, bridges and ports unusable.Hospitals and clinics were washed away, collapsed, orwere so badly damaged that they became inoperable.

In the immediate aftermath of the tsunami, the militaryand teams of volunteers raced to bury the tens ofthousands of bodies that littered the streets, weretrapped in the debris and cars, or were even found intrees and on top of buildings. Across Aceh, 130,736people were killed and 37,066 people left missing; morethan 100,000 bodies are now buried in mass graves.Among these were thousands of individuals whoseskills would have been vital to the emergency reliefeffort: health personnel, police and military, and localgovernment officials and civil servants.

Meanwhile, with around 123,000 houses destroyed,some 514,150 people fled to refugee camps, with anestimated similar number moving in with relatives orfriends or building makeshift huts. Some of the moreremote camps lacked food and many were short ofpotable water and sanitation facilities. In the first fewdays, the shortage of clean drinking water, medicalassistance, medicines, and lack of sanitation created apotential public health emergency.

As the waters receded, it became evident that hundredsof thousands of livelihoods had been destroyed.Thousands of fishing boats were damaged and lost,along with half of the existing fishing industryinfrastructure. Meanwhile, 25,840 out of 36,614hectares of brackish water shrimp/fish ponds (tambak)were damaged. In addition, fields and plantationsdisappeared under water, or became so silted up withmud and salt that they were rendered useless. In theagriculture sector, 57,758 hectares of irrigated land, and29,948 hectares of non-irrigated agricultural land weredamaged and in need of minor or extensive repair.Irrigation networks in these districts were alsodamaged. Thousands of head of livestock were lost. Intotal, more than 240,000 families traditionally involved inthe agriculture sector lost their livelihoods, and riceproduction in 2005 decreased by 397,504 tons from theprevious year.

The province had also suffered terrible damage toinstitutions critical to its long-term reconstruction. Theprovincial government and many local leveladministrations were devastated, suffering substantialloss of personnel, expertise and infrastructure: inFebruary 2005, it was announced that 2,992 out of atotal of 77,530 registered civil servants in Aceh werekilled, with a further 2,274 still missing. District, sub-district and village level governance was alsoweakened; many current (sub-district heads) and

(village heads) have been appointed post-tsunami. The damage to the health and education

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

camatkepala desa

II. Aceh and the tsunami

sectors was substantial. More than 500 health workersdied or are missing, 8 hospitals were damaged, and 114health centres. In education, over 380 schools weredestroyed, and 954 damaged, and more than 2,000teachers are dead or missing. The Department ofReligious Affairs also reported that 209 of its(religious schools) and 155 (traditionalIslamic boarding schools) were damaged. The StateIslamic Institute (IAIN), one of the biggest and mostprestigious universities in Aceh, sustained substantialdamage; the Directorate General of Higher Educationreported that as many as 200 university lecturers acrossthe province were killed. The local media infrastructurewas also ravaged. Aceh's daily newspaper,

, was unable to cover the biggest story in itshistory: located only 500 metres from the coast,

office and printing presses were destroyed,and almost half of its staff killed. Banda Aceh also lost16 radio stations, while in Meulaboh on the west coast,all four local radio stations were either completely orpartially destroyed.

By the evening of 26 December, Indonesian PresidentSusilo Bambang Yudhoyono declared a nationaldisaster and ordered line departments and ministries tomobilise available resources for the emergencyresponse and recovery processes. For the emergencyrelief and rescue efforts, Vice President Jusuf Kalla wasappointed to lead an existing government emergencymechanism, the National Coordinating Board forDisaster Management and IDPs (BAKORNAS PBP). Inthe days immediately following the disaster,BAKORNAS PBP was mainly tasked with providingimmediate assistance to tsunami survivors in the formof search and rescue, food, shelter, and medical help,as well as with burying the dead. In these tasks, theywere joined by the forces both of GAM (which declareda unilateral ceasefire on 26 December and joined inrelief efforts) and of the TNI (which, to a far greaterextent than GAM, had itself suffered significant lossesof life and equipment). Some 15,000 of the 40,000 TNItroops in Aceh were detailed to the humanitarian reliefoperation, and an additional 12,000 troops were sent toAceh on 14 January 2005 to hasten the burial of bodiesand clearing of debris. These efforts were quicklyjoined by thousands of volunteers from the provincialgovernment, the centra l government, re l ieforganisations, and communities from elsewhere inIndonesia.

During the first days after the disaster, Aceh remainedclosed to outsiders, as it had been during both martiallaw and the subsequent civil emergency. It soonbecame evident, however, that the scope of the disastermade outside assistance imperative. On the afternoonof 28 December 2004, the Indonesian governmentformally requested the help of the UN and others for therelief effort. In particular, Kalla invited the UnitedNations Office for the Coordination of HumanitarianAffairs (UN-OCHA) to coordinate the international reliefeffort and international aid workers. Many relieforganisations had already dispatched emergencymedical and rescue teams to stand by in neighbouringareas waiting for permission to enter Aceh. When theprovince was opened on the evening of 28 December,international NGOs and foreign government relief teamsstreamed in. Meanwhile, foreign militaries arrived in

madrasahpesantren

SerambiIndonesia

Serambi's

Humanitarian response: the emergency phase

13

14

6

Aceh with helicopters, transport aircrafts and ships tofacilitate the movement of logistics and key personnel tothe areas that were cut off. A TNI press release on 17January noted that 4,478 foreign troops were already inAceh. Any immediate or real threat to the lives ofsurvivors was minimised by international teams playinga key role in providing health services, temporaryaccommodation, and clean water for survivors.

It soon became evident that massive international fund-ing would be necessary across the tsunami-affectedregions not only for the emergency relief effort, but alsofor longer term reconstruction efforts. Many donorsrapidly rose to the occasion. Within only a few hours ofnews of the tsunami, the EC, through its humanitariandepartment ECHO released €3 million ($3.6 million) inimmediate assistance for the region, with a further €20million committed later that week. The UNDP alsoreleased funds ($500,000) on the same day,and by 27 December, Australia had already dedicatedA$10 ($7.5) million to tsunami-affected regions; manyothers scrambled to respond quickly. A few days afterthe tsunami, the international community had alreadypledged half a billion dollars for support to the affectedcountries in the region. That figure jumped to more than$800 million by the end of December 2004, when theUnited States increased its pledge from $35 million to$350 million. On 6 January 2005, the UN SecretaryGeneral launched a Flash Appeal for the affectedregion. At a meeting in Geneva on 11 January, donorspledged 77% of the $977 million requested forimmediate relief ($371 million of which was forIndonesia). By 6 April 2005, a midterm review of theFlash Appeal adjusted the amount needed across thetsunami affected region upward to $1.087 billion. Theallocation for Indonesia alone had increased to $396million. A further review of the Appeal is planned for theperiod January-June 2006; it is likely that the total willrise again.

Meanwhile, the outpouring of private charitabledonations worldwide was unprecedented; eventuallyreaching $2.5 billion. In Britain alone, the publicpledged 20 million ($35.35 million) in less than 48hours after the UK Disasters Emergency Committee(DEC), an umbrella group for a dozen British charities,launched its Tsunami Earthquake Appeal on 28December 2004. American private donations fortsunami affected countries were estimated at around$1.3 billion; Australian private donations to NGOstotalled A$375.3 million ($281.1 million). Manyorganisations indeed ended up closing their appeals; forinstance, the DEC closed its appeal - the biggest-everfundraising campaign in UK history - on 26 February2005, after raising more than 300 million ($528.8million). The Red Cross organisations also stoppedtaking donations, as did many others.

In this context of generous giving, both the Indonesiangovernment and the international community movedrapidly to determine the country's needs. Indonesianline ministries, in particular the National DevelopmentPlanning Agency (BAPPENAS) was tasked withdocumenting the loss and damage of assets and theanticipated costs of reactivating local government andsocial services. Hundreds of (temporarycoordination centres) sprang up throughout Aceh, and

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

£

£

Shifting from relief to reconstruction

poskos

7

acted not only as distribution points but data collectioncentres. The estimated total damage and loss for Acehand affected areas of North Sumatra was totalled at$4.5 billion - 97% of Aceh's pre-tsunami annual grossdomestic product (GDP). After a subsequentearthquake on 28 March 2005, the damage and lossfigure increased to $4.8 billion. The total estimatedneeds for long-term recovery and rebuilding ofIndonesia's tsunami-affected regions were $5.0-$5.5billion.

In response, donor pledges were generous. Accordingto the United Nations Special Tsunami Envoy, as ofDecember 2005 the total funds pledged by theinternational community for Indonesia's long-termrecovery came to $6.1 billion. Of the funds pledged,approximately $3.6 billion is from multilateral andbilateral donors and international financial institutions,with another $2.5 billion from NGOs, the InternationalFederation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies(IFRC), and others.

In June 2005, the Indonesian Parliament approved anincrease in the National Budget allocation for Aceh fromRp 10.7 trillion ($1.15 billion) to Rp 13.3 trillion ($1.4billion) to contribute to the rehabilitation and recon-struction process. Of the $1.4 billion total, Rp 8.8trillion ($948 million) comes from funds released bynternational creditors' debt moratorium and the resche-duling of foreign loans; Rp 3.9 trillion ($420 million) inthe form of grants from foreign governments, and Rp 0.6trillion ($420,000) from re-allocation of project loans.

While there thus is no shortage of funds for post-tsunami needs, the money has not been flowing toprojects as quickly as expected. Some donors, such asthe AIPRD, lacked capacity to implement programmesquickly after the disaster and came under muchcriticism at home for slow disbursal of funds, whileothers, such as the ADB and World Bank, chose tochannel funds on-budget. Indonesian governmentfinancial mechanisms, newly reformed to promotesound financial management, were unable to cope withthe sudden influx of such large amounts of money.Extensive bureaucratic requirements, including a newlydevised programme planning and expendituredocument have caused long delays, with grantdisbursement approval often stuck in the Ministry ofFinance. Under the coordination of the line ministries,new working units put in place to submit draft activityand budget plans also caused delays; according to anofficial from the ADB: "Staff were slow to understandthe new mechanism, which was in fact itself poorlydeveloped." It is not unusual to hear officials of somelarge on-budget donors complain about the lack ofcapacity within these government ministries to deal withtheir own mechanisms. As one senior diplomatremarked: "Indonesia is an incredibly over-bureaucraticcountry. But if we try to interfere in that bureaucracy, thewheels will turn even more slowly." There is alsofrustration within the BRR. An Indonesian officialconcurs with the generally held view: "The excessivebureaucracy is making processes laborious and veryslow. We really need the finance department to show asense of emergency in this very unusual situation."

The excessive and inefficient bureaucracy has had

22

23

24

25

i

26

27

28

29

30

Bureaucratic delays: the dilemma of on-budgetmechanisms

significant impact on the rolling out of many projects,for instance those of the ADB. In April 2005, the ADBadopted a $290 million grant agreement with theIndonesian government to fund 12 sectors andimplemented by the various line ministries. However,grants did not even begin to reach the localdepartments in Aceh until late November 2005. TheADB said its programmes had been frustrated by thedelays caused by the complicated bureaucracy in theMinistry of Finance, and that the ADB had been inconstant correspondence with Jakarta in an effort torelease blockages. The head of the Department ofAgriculture in Aceh was also frustrated after waiting sixmonths for the ADB money, and afraid ofmismanagement and waste if the programme had to beimplemented too quickly. "The Department of Agicultureis scheduled to receive Rp 72 billion ($7,754 million) tobe spent on repair and development of the agriculturesector between September and December 2005," hesaid. "But this is already November, and the money hasnot yet arrived, how can we spend it? I want thegovernment to extend the programme implementationperiod until April." When the grant eventually reachedthe department in late November, an extension untilApril 2006 had been granted.

Similar frustrations have also been experienced by theMDTF, which has also channelled significant amountsof funds via on-budget mechanisms for variousprogrammes. One programme whose start was delayedwas the MDTF's "Reconstruction of Aceh's LandAdministration System" (RALAS) programme. Ir. RazaliYahya, head of Aceh's branch of the National LandAgency (BPN), was not happy. "This process of landownership should have begun much sooner", he said."But the problem is that the MDTF insisted the moneybe channelled on-budget, via the Ministry of Finance,and we had to then submit a complicated budget andplanning proposal. We effectively received the moneyear ly October , and began the programmeimmediately." A representative of the MDTFresponded: "I am not saying the government's processis bad, but it is definitely slow. However, this is agovernment mechanism, and we cannot interfere inthat. But what we can do is to tell them that theirbureaucracy is very, very slow."

The terrible devastation caused by the tsunami had onepositive effect: GAM and the Indonesian governmentreturned to the negotiating table for further talks on howto reach a peaceful solution to the long and violentconflict. Several rounds of peace talks took place in thepost-tsunami environment, which not only carried addedurgency but was also more politically congenial tocompromise than that of previous negotiations. Finally aMemorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on15 August 2005 that was wide-ranging and aimed atsustainable peace and continued dialogue. Theagreement leaves many issues for further negotiationand compromise and cannot be seen as a fullguarantee of peace, but it does contain a greatermeasure of political good will than previousagreements. GAM has fulfilled its commitment todecommissioning a pre-agreed number of weapons(which it says are all its weapons); in return, theIndonesian military has withdrawn significant numbers

31

32

33

34

Reconstruction efforts assisted by new peaceagreement

8

of its troops.

Many political, social, and economic issues arenevertheless sure to arise as the MoU unrolls in theshort and medium term. And potential spoilers exist onboth sides within GAM and the Indonesian securityforces and their proxy militia armies. The unarmed AcehMonitoring Mission (AMM), made up of representativesfrom the EU, five ASEAN countries, Switzerland andNorway, is tasked with supporting both sides in theirattempts to adhere to the spirit and letter of theagreement, to monitor implementation, and to rule ondisputed cases; but its task is vast and the road aheadis potentially troubled. The implementation of the MoUhas certainly calmed what was a volatile post-tsunamisecurity environment, making it much easier for donorsto travel around the province, and paving the way for aless troubled implementation of programmes. The

A variety of Indonesian government arms have been tasked with Aceh-related responsibilities. The NationalCoordinating Board for Disaster Management and IDPs (BAKORNAS PBP) was tasked to coordinate theemergency relief and rescue operations, as well as recovery in the emergency phase. In oversight of theemergency relief effort on a day-to-day basis, a provincial extension of BAKORNAS PBP, the ProvincialCoordinating Board for Disaster Management and IDPs (SATKORLAK PBP) took control. At the districtlevel, these boards are known as Implementation Units for Disaster Management (SATLAK PBP).Meanwhile, the National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) has been charged with coordinatingthe work plan and funding for longer term rehabilitation and reconstruction. BAPPENAS was charged withpreparing a blueprint or master plan for rehabilitation and reconstruction of Aceh and Nias island, finallysubmitted on 15 April. The Department of Finance, together with BAPPENAS, is responsible forcoordinating the funding and controlling the finances for rehabilitation and reconstruction.

Meanwhile, there was an immediate need for an oversight body that would coordinate overall rehabilitationand reconstruction Aceh. The Bureau of Reconstruction and Rehabilitation (BRR) was established bypresidential decree on 29 April 2005 to ensure a coordinated approach to planning, fundraising andimplementation. The bureau's initial operational expenses were covered by $12 million from the IndonesianMinistry of Finance; the bureau also relied on assistance to start from the Australian government, andcontinues to receive funds and technical support from many donors. The MDTF has committed $ 14.7 millionto the BRR, and is providing technical assistance for human resource management, quality assurance andlegal services, project management and other assistance. There is also significant information technologyassistance, and an emphasis on monitoring to ensure a corruption-free process. The UNDP has also beencharged with recruiting technical assistance, although the process has been subject to some delays due tobureaucratic bottlenecks within the UNDP. Furthermore, because the issue of foreign technical assistancehad not been adequately socialised among local BRR employees, many feared that foreign assistancecoming in would result in changes to systems that people had already worked hard to put in place. Theseproblematic issues have now been worked out, but caused unnecessary delays earlier on.

35

36

The Indonesian Agencies Working on AcehBox

quantity and quality of the reconstruction programmewill potentially have a profound impact on thesustainability of the new peace. Some donors haverecognised the need for cross-mandate activities thatwill include ex-GAM soldiers and conflict-affectedcommunities. For example, the World Bank hasconducted GAM reintegration needs assessments,aimed at providing information to help understand thedevelopment needs of former combatants and theircommunities, and to consider current reintegrationprogramming and potential obstacles. In essence, thesequalitative assessments are aimed at identifying whatdevelopment programmes might be included that willhelp to strengthen the peace process. The EuropeanCommission is also providing support to assist inmeasures to reintegrate former GAM combatants intocivil society and democratic political life, and areconsidering assistance to wider conflict areas.

9

III. A people's reconstruction agenda?

The reconstruction process

Difficult problems, difficult choicesAid donors and implementers have faced manyconstraints in their reconstruction and developmentoperations. Donors and implementers, their effortscomplicated by high staff turnover in Aceh and theirown internal bureaucracies as well as that of theIndonesian government, have had to grapple with amyriad of complexities related to rebuilding in sucha damaged environment with shortages of availablematerials, as well as with the logistical and financialproblems of moving and purchasing materials in asituation where roads, bridges and ports have allbeen damaged and where prices have been risingdramat ica l ly . The fact that the Indones iangovernment lacked a coordinating agency fortsunami aid until April 2005 meant that in manyc a s e s p r o j e c t s w e r e l a r g e l y d e t e r m i n e duni lateral ly, and in a very ad-hoc manner.Uncertainty over an Indonesian prohibition (nowlargely ignored) on building within 2 kilometres ofthe coast as a safety measure only added to theconfusion. And other issues have presentedthemselves as well:

The tension between building back fast and buildingback well. There is an obvious tension between theneed and desire for quick results and the need forinterventions to be done in a correct and sustainableway, which inevitably requires a longer planning period.In the enormous outpouring of public, corporate andgovernment sympathy that drove the tremendousfinancial response, there was an immediate andpressing sense of obligation on the part of the donorsand implementers, to show that results could be fast,visible and wide-ranging. Hence, tremendous pressurearose to disburse large amounts of resources veryquickly.

The tension between simple reconstruction andbuilding back better. The state of pre-tsunamiinfrastructure in Aceh was poor, due to years of under-investment by the government and a lack of privateinvestment due largely to Aceh's volatile securityenvironment. The reconstruction efforts present aunique opportunity for the improvement of sewage anddrainage systems, roads, schools, clinics and otherpublic infrastructure, as well as for the establishment ofnew facilities such as libraries, pre-school facilities, oremployment centres. But such improvements, whichrequire careful planning, take time.

The problems of working in an infamously corruptenvironment. Both donors and the Indonesiangovernment have taken steps to combat corruptionwithin the relief effort, but the issue has consumed timeand resources that might otherwise have been availableelsewhere.

The problems inherent in working with a traumatised,dispersed population with a low skills base, few or noresources, and severely damaged social structures,most of whom had no previous exposure to aidagencies, and the working practices of the UN, bilateraldonors, INGOs and others.

•

•

•

•

In this difficult environment, most donors have madestrong on-paper commitments to high standards ofpractice, including a commitment to gender sensitivity,env i ronmenta l protect ion, consul ta t ion wi thbeneficiaries, and the implementation of anti-corruptionmechanisms. For an overview of the programmes of thefive donors on whose projects this study draws, seeAppendix 1, page 43

The 50 or so programmes that this study surveyedvaried widely in their scope, their objectives and theirimpact on local communities. Virtually all projects hadaspects that had gone well; most had also faceddifficulties in at least a few areas. In looking at theimpact of programmes, we tried to think not only abouttheir current impact, but also about their probableimpact in the months and years to come. In this context,a few consistent areas of concern emerged.

Pre-project needs assessments are vital to thesuccessful identification and design of rehabilitation andreconstruct ion act iv i t ies. They help donorsconceptualise and prioritise projects, as well as to layout provisional budgets. For the most part, however, wefound that donors and implementers rarely consultedwith communities (or indeed each other) during the pre-project assessment process. Such consultation mighthave helped ward off future problems, includingineffective or inappropriate projects or waste.

For example, better community consultation might haveled to less wastage of small grants. Many donors areimplementing small grants schemes in areas where nopre-tsunami economic profile has been conducted. Insome of these areas, however, many of the businessesdestroyed were medium-sized businesses, whoseowners neither want nor need micro-credit. In BandaAceh, for example, many of the communities now leftdestitute by the tsunami were in fact quite wealthy byAcehnese standards, and would like to restart thebusinesses they lost at the level at which they werepreviously operating. These people need access tolarger credit facilities than are currently available fromdonors. Moreover, the small grants on offer - whichusually do not exceed $250 per person - are inadequateto begin a business in Aceh's high inflation economy.As a consequence, small grants given out by donorssuch as Mercy Corps, Oxfam, IOM, CHF, IRD, WorldVision and many others are sometimes used to repayexisting loans, buy second-hand motorbikes, repairdamaged housing, or other "non-business" activities.Aminah and her friend are not untypical: the smallbusiness grant of Rp1.5 million ($162) received fromIRD was spent on new hand phones. "What do theyexpect us to do with that small amount of money?Actually, we don't want to begin a small business butthey offered the money, so we took it. Our husbandsneed a loan to restart their previous business. Thatwould be more useful, but is not available," she said.(See "Grants versus Microcredit," page 21). Efforts topull together groups into cooperative or communalbusinesses, or even to open small kiosks or begin homeindustries, are encountering similar issues of localappropriateness.

Consultation and communication

Consultation during pre-project needs assessments

37

38

1

Donors have struggled to figure out how to deal with Indonesia's endemic corruption. The government does nothave a good reputation for public finance management. This is one of the main reasons many of the donors tothe Multi Donor Trust Fund give for channelling funds this way. The EC decided to channel its longer term aidthough the MDTF: "The World Bank, as a trustee of the Fund, has the capacity to ensure transparency andaccountability. We needed to be sure there is no leakage from our aid, and we are confident that the Fund'smechanisms can do that." The ADB's on budget mechanism also requires that they pay special notice to theissue of leakage. Therefore, the ADB has made it a core component of its work to be involved in several of theanti corruption mechanisms relating to the reconstruction process in Aceh. The ADB is working with the existingCorruption Eradication Committee (KPK), a government mechanism that has recently undergone reforms as partof the effort to rid the country of the endemic corruption for which it is infamous, and has also placed consultantswithin the BRR to assist with policies and processes for best practice "not only for our own grants, but to ensureall donors are protected against possible loss of funds. In this effort, we collaborate with others such as theauditing firm Ernst and Young."

Meanwhile, the chief of the BRR, Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, is himself keen to ensure the agency is "free fromKKN (corruption, collusion and nepotism)." As part of these efforts, the BRR established an Anti-Corruption Unit(SAK) as a joint initiative with Indonesia's KPK; its main operating components are corruption prevention,investigation, education and the enhancement of integrity. The establishment of SAK was encouraged and issupported by foreign donors. A BAPPENAS official explained: "Basically, the donors pushed SAK on the BRR.They have given so much money to Indonesia for Aceh's reconstruction, and they will continue to give overseveral years. It's important for them to be sure government officials are not siphoning off some of those dollarsfor themselves." SAK has actively sought out cases of existing and potential corruption; between its inception inmid-September 2005 and mid November 2005, it received 120 reports, 20% of which were related to the issue ofpotential corruption, 18% were related to the issue of corruption in tender process, and 16% related to the workethic of BRR staff.

39

40

41

42

43

Donor and Indonesian anti-corruption mechanismsBox

underway. Of those waiting for houses, around67,000 live in tents, and between 60,000 to 70,000in barracks. The remaining live in makeshift huts,or with relatives and friends. The process ofproviding housing in Aceh is inevitably slow due tothe complexities of the task. Land ownership mustbe confirmed before building can take place; someland remains under water; there are greatdifficulties in transporting building materials; ashortage of legally-sourced wood; water andsan i ta t ion fac i l i t ies take t ime to p lan andimplement, and clean water has to be trucked in tosome areas. All of these factors conspire to stymiethe efforts of agencies involved in the housingsector. The magnitude of such logistics problemsand the often vocal impatience of Acehneset rapped in tents or unsat is fac tory bar rackaccommodation serve to compound what oneforeign NGO worker calls "the misery of working onhousing in Aceh." In such an environment, greateragency coordination and collaboration (instead ofthe usual competition), and consultation with localpeople, would go at least some of the way towardalleviating these problems. As it stands, manyimplementers view adding on a potentially lengthyconsultation process as a recipe for disaster, onlycomplicating matters and lengthening delays. Ourresearch suggests, however, that the frustration ofthose waiting for housing could be substantiallyreduced by employing a more interactive method ofhousing design. The frustration and anger thatmany local people feel in the face of delays is oftengreatly compounded when they see houses beingbuilt that are unsuitable to their family's needs. Forexample a housing project for civil servantssponsored by the Queensland government ofAustralia has resulted in houses that the occupantsdo not wish to inhabit (see "Going it Alone is Risky,"page 27 ). Some communities, however, such asthose working with the Catholic Relief Services(CRS) in Meulaboh have been given toolkits,materials and the necessary technical assistance

44

45

10

By contrast, the World Bank's Kecamatan (Rural)Development Programme (KDP) and the Urban PovertyProgramme (UPP), two community-driven developmentschemes, whilst not without problems, have given somemeasure of input for the local population into the needsassessment process. These schemes, which makeblock grants available to local communities for publicinfrastructure, are implemented through a system ofsub-district and village facilitators, in coordination withtechnical experts, consultants and province andprogramme coordinators. The job of facilitators is tocoordinate participatory planning meetings and toensure broad consultation on the priorities of the villagein preparation for submitting the proposal on theinfrastructure projects for which the block grant isrequested. Several hundred new facilitators have beenrecruited and trained to support the programme's post-tsunami expansion. During the emergency period, some25% of the local block grants funds were madeavailable to meet urgent and immediate needs ofcommunities.

Once needs assessments have been conducted,consultation with beneficiaries over project designcan also help ensure appropriate and sustainableoutcomes. This study found, however, that all toocommon failure to consult with beneficiaries oftenled to potentially highly successful projects goingbadly awry, leading to wasted funds and leavingbeneficiaries frustrated and demoralised, whiledonors who do consult often have more congenialrelations with local communities, and better projectoutcomes.

Two areas extending across many donors andimplementers that suffered badly from lack ofcoordination were those of housing and fishingboats. Twelve months after the tsunami, withalmost 500,000 people still displaced, only 16,200houses had been completed, with another 13,200

Consultation during project design

Although most donors and implementers consulted national and local government officials at least to somedegree during the needs assessment phase, few mechanisms exist for consultation of civil society groups. Theactivities of civil society groups - non-governmental organisations, civic action groups - were severely disruptedduring the conflict in Aceh, very few NGO councils or other mechanisms exist that could bring togetherrepresentatives of Acehnese NGOs. Some of those formed in the wake of the tsunami, such as the AcehRecovery Forum, have also experienced a loss of local confidence as they move farther out into the politicalarena. Some local NGOs, for example the Aceh Legal Aid Foundation (LBH-Aceh), have attempted to engagewith international donors, for instance through the production of ad hoc recommendations; regular informaldiscussions between implementing international NGOs and some local NGOs also occur. A regular participant atthese meetings said that the impact on policy or implementation is minimal: "It seems that these internationaldonors have their own agenda; they will not change that whatever we say."

The MDTF, alone among donors, has two civil society representatives on its Steering Committee. In interviewsfor this report, however, neither of the Acehnese representatives, Naimah Hassan nor Humam Hamid, seemedto understand why they had been appointed to this body nor by whom these appointments were made. BothHassan and Hamid said they make no claim to representing civil society on the Steering Committee, as theywere not elected by the Acehnese people. Hamid stated: "When the person from the World Bank asked me toparticipate in the Steering Committee, I told them I thought it would be a conflict of interests because I am on thesupervisory board of BRR. But they said that is no problem." Hamid intimated that there were minimaldiscussions before and after his appointment and that he has (by November) been to only two meetings. "I wastold by the MDTF I was the civil society representative but they never explained why I was appointed, and whatmy rights and responsibilities are." The Trust Fund secretariat is aware that the system is imperfect. "We areaware that the civil society representatives "are not wholly representative, but we had no alternative at thetime," said the Trust Fund manager. Moreover, he continued: "To embark on a process of democraticallyelecting civil society representatives would be long and arduous. But it is better to have some level ofrepresentation than none." The seventh meeting of the Steering Committee took place in December, with still nosign of any moves to make the civil society representation more representative.

At the same time, very few people within Aceh know of the existence of Acehnese representatives on theSteering Committee. Several months after its establishment, leaders of some of the larger civil society networksin Aceh were surveyed to assess the level of input to the Trust Fund's process. Of ten interviewed, only twowere aware of any civil society representation. A representative of the Aceh Institute commented: "I know bothNaimah and Humam in their private capacity, but I had no idea they were sitting on the Steering Committee ofthe MDTF f they are representing civil society, [they should] coordinate with other civil society actors."Moreover, Chair of the influential Ulama Consultative Council (MPU), was not even aware of the existence of theMDTF. Both representatives on the Steering Committee admit that few Acehnese are aware of or understandtheir roles, positions or activities in the Trust Fund. Hamid explains: "If the Trust Fund wants us to socialiseideas and gather opinions here in Aceh, then they should give us financial resources to do so. But they do not."By November, the MDTF had adopted a policy to socialise its activities to the communities in Aceh in preparationfor the unrolling of its programmes, such as housing, and others that will directly involve the communities on aday-to-day basis. Yet more clearly must be done for the MDTF or the Acehnese community to reap benefits fromthe presence of these 'civil society representatives' on the Steering Committee.

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

. I

A voice for civil society?Box

fishermen themselves. Indeed, if one travels thecoastal area of Aceh, many 'aid boats' can be seenunused. The engines or other parts have usuallybeen taken to use in other boats or to sell.Frustrated at the lack of positive response to theirlobby ing e f fo r ts w i th in te rna t iona l donors ,Panglima Laot said "the most important thing formany agencies is to be able to say they have givenboats; whether or not the boats are then used is oflittle concern to some donors." The fishingassociation has further recommended that donorsand agencies stop distributing boats under sevenmetres, as well as to consider environmentallyfriendly nets and other equipment.

For example, ECHO gave the Agency for TechnicalCooperation and Development (ACTED) nearly $1million for the much-needed construction and purchaseof seagoing boats and equipment for fishingcommunities in Nagan Raya and Aceh Barat districts.The first ten boats were handed over to fishermen inNagan Raya in June 2005. However, five months later,none of the boats had ever been used for fishing - noteven in the river.

55

56

11

to rebuild their homes, while those assisted byMuslim Aid in Kampong Jawa, Banda Aceh, areable to adapt a basic design to suit their own needs,even negotiating the size of the house dependingon the number of people in the family. In suchcircumstances, community shelter meetings aremuch less heated affairs.

Meanwhile, the need for boats to replace thethousands lost in the tsunami was real and urgent.Many donors or implementers, however, did notconsult with the local fishermen about the type andsize of boat needed. According to Aceh's traditionalfishing association, Panglima Laot, almost half ofthe thousands of boats donated after the tsunamiare ei ther ent i re ly inappropr iate for Aceh'streacherous waters or are too small (under 7metres) to be used outside coastal waters andrivers, with implications for over fishing of coastalzones (see page 30). In some places, people weregiven boats of a poor standard, and some receivedno fishing equipment or funds to cover initialoperational costs; in other cases beneficiariescomplained that the nets given with the boats werethe wrong type, and had to be replaced by the

54

When the earthquake and tsunami struck Aceh, the World Bank's KDP programme was already beingimplemented in 87 of Aceh's 220 rural sub-districts; with additional $68 million funding post-tsunami from theMDTF, it has expanded to all rural areas in Aceh. The KDP's urban counterpart, the Urban Poverty Programme(UPP), already a common feature elsewhere in Indonesia, also was introduced after the tsunami into Aceh'surban areas with a grant of $18 million from the MDTF.

Both the KDP and the UPP are promoted as "community-driven development" (CDD) programmes - the formerbeing one of the largest CDD projects, according to the World Bank, in East Asia. The KDP/UPP processes aimto facilitate community-driven development using its network of 1,450 facilitators to initiate village forums todiscuss local infrastructure needs and provide channels by which that information then makes its way to the sub-district and district levels. A KDP trainer explains the ethics he tries to instil in the network's sub-district facilitatortrainees: "I tell the new recruits that as a KDP facilitator, their job is to hold discussions on the initiatives andpriorities of the local villagers. I tell them 'Be careful there is no outside influence in this discussion. You must besure these priorities really are those of the village as a whole. Actually, their job is very simple: always representthe wishes of the people, always negotiate on the community's behalf, and always be open and honest withthem." The Chief of the BRR is very much in favour of such programmes: "The mechanisms used by the [WorldBank's] rural and urban community recovery projects are strong community-driven platforms. [They] can and willbe used by other NGOs and organisations; this is in line with the BRR's principle of using a bottom-up approach.This will greatly enhance an effective reconstruction and rehabilitation process of Aceh and Nias, led by thecommunities themselves."

This study, however, found reason to be concerned about the use of the KDP and UPP mechanisms to informcommunities of project plans that have been formulated by others with very little or no community discussion,rather than to collect information from the villagers about their community's own priorities and to assist them inconceptualizing and designing their own projects. KDP personnel are trained to facilitate discussion amongvillages and to communicate their priorities upwards, not act as messengers from donors to the communities.Increasingly, however, the KDP mechanism is being employed as an implementing mechanism, and as achannel of communication from the top down. For example, in relation to the construction of village offices andvillage halls in the sub-district of Baitussalam, Aceh Besar, the AIPRD has been sending messagesdown the KDP system about timing and other related issues. Local KDP facilitators explained: "Our role here isreally only to pass messages to the people when the Australian representatives tell us to do that. And to be surethat the money that comes to the KDP bank account is spent as it should be, that's all." This places KDPfacilitators in an awkward position with the local communities, as they are reluctant to reveal the truth aboutdelays and other problems relating to the AIPRD-funded village office programme. "We don't want to talk to thevillagers in case there is a further delay, or the programme is not implemented in all villages. To be honest, we[KDP facilitators] don't really know how to tell the people," said one facilitator. "The Australians say they will giveus training later this month, perhaps after that we can socialise the idea of village offices in Baitussalam." Theuse of the KDP and UPP as mouthpieces for donors and implementers, rather than for communities, willeventually lead to the community feeling distanced from the KDP/UPP mechanism, and will erode the integrity ofthe whole KDP/ UPP network.

59

60

61

62

63

(meunasah)

Protecting the KDP/UPP processBox

12

"We don't want to use these boats," a local fishermansaid. "They are not the usual boats we use around here.It would be dangerous to take them outside the river.ACTED never consulted with us about the boats. If theyhad asked us for input, we would have been very, veryhappy to help. They didn't, and now the boats are sittingin the water - they cannot go anywhere."

Fishermen in Aceh Besar working with a French NGOTGH have a quite different experience: discussionswith the TGH staff, local boat makers as well as an'open invitation' to visit the boat shed to check on thequality and progress of the boats being made for themhas led to a sense of ownership in the process, andgood relations between the donor (TGH) and localcommunities. (See"TGH aid boats - still afloat," page31).

By contrast, staff at the emergency department of theZainoel Abidin General Hospital (RSUZA) in BandaAceh, which is being rehabilitated under a partnershipagreement between the AIPRD, Indonesia and

57

"We don't really want the boat from ACTED,but we will take it. It's an 'aid' boat - that's all."

Abdul Manaf, Nagan Raya, 13 December 2005

Germany, reported a highly successful consultativeprocess, both during the needs assessment processand in project design. The process of reconstructing thehospital's emergency facilities was a collaborative effortbe tween sen io r hosp i ta l s ta f f and AIPRDrepresentatives. "I've very happy with the newdepartment," said the head of the hospital "Wedesigned the layout ourselves, and the new equipmentis exactly what we requested." Staff will be trained inthe use of the more advanced equipment before thenew department becomes fully operational early thisyear.

One of the most common areas of concern amongbeneficiaries was lack of information, explanation andongoing consideration. Many beneficiaries seem tohave only a vague idea about what was involved inprojects; until and unless the communities actually sawthe progress of the project in its physical form, therewas often a very low understanding of what exactly theproject would deliver, and little awareness of aprogramme's timeline The lack of information madepeople feel helpless, and often made them questionwhether absent donors and implementers were sincerein their commitments to return to the village at all,

58

Social accountability to beneficiaries

Inadequate communication can leave communitiesconvinced that implementers have abandonedthem. This problem has been particularly acute inrelation to housing. Many communities have waitedfor NGOs such as CARE in Simeulu, Oxfam inBlang Oi, or Samaritan Purse in Aceh Jaya, andother agencies such as the ADB in Lambada Lhok,to return to fulfil earlier commitments to buildhouses. Not wanting to renege on agreementsmade, the communities have turned down offers ofhousing by other donors. In September, the iin Aceh Jaya said that of the 12 MoUs signed withimplementers, most remained unfulfilled. Hisfrustration was evident: "We just called SamaritanPurse and told them if they don't fulfil what theypromised, they will no longer have an MoU. I willcancel it. The same for the others who do notrespect our desperate needs or the agreement theymade with us." he said. "The Turkish governmenthas delivered the houses it said it would, the others- not yet."

Bupat

64

Feeling abandonedBox

For example, in the AIPRD's project to construct villageoffices and in the sub-district of Baitussalam,lack of information flow described above was taking itstoll. When researchers interviewed the head of onevillage in October, he had been waiting for his AIPRD-funded village office for several months, and was underthe impression that construction would begin inNovember. A follow-up visit in early January 2006 foundhim losing patience: "I don't have any more news sinceyou were last here. Nobody has been to tell us thelatest update on our village office, and you can see foryourself it has not even begun. No Australians or theirrepresentatives ever came to meet us here." The lackof information flow has created a climate of virtualindifference in some villages in Baitussalam; some nolonger believe their own village will receive an office aspart of this programme - and many, it seems, no longercare: "if they build us an office, ok. If they don't, whatshould we do? We have become professionals at thewaiting game - but it's a boring job, and with no pay."

By contrast, the UNICEF child centre programmeimplemented with the help of Muhammadiyah on thewest coast of Aceh is an example of where the two-wayflow of information has led to the implementation of asuccessful programme. The programme was interactivein the planning stage, and retains a rolling mechanismof evaluation and discussion involving the parents of thechildren at the centres, the village elders and centrestaff. At a two-week staff training course before thecentres opened, negotiation, communication, and

meunasah

65

66