8th May 2020

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

8th May 2020

IT was a time of celebration, it was a time to sighwith relief that five long years of war had finallycome to end. On the 8th May, 1945, after his radio

broadcast, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchillspoke to the jubilant crowds at Whitehall, “God blessyou all! This is your victory! It is the victory of thecause of freedom in every land. In all our long historywe have never seen a greater day than this. Everyone,man or woman, had done their best. Everyone hastried. Neither the long years, nor the dangers, nor thefierce attacks of the enemy, have in any way weakenedthe independent resolve of the British nation . . .” And so Britain and her Empire celebrated. Althoughthere were no official plans for a celebration,nonetheless VE-Day was a time of rejoicing by themasses of people who had gathered outsideBuckingham Palace and along the Mall to voice theirappreciation to their king and his family who hadstood firm and endured with the rest of his subjectsanxiety, and desperation. Those who could, tried toforget how it had been for nearly six years. Those whocould, mourned their family or friends who were dead,wounded, missing or were in POW camps. But this daywas a time for hope and thanksgiving and to rememberthose that had fought for a better Britain and a betterworld.In our own Province of Surrey, Freemasons and theirfamilies too faced daunting times. Many younger menin Lodges either volunteered or were conscripted intothe forces. Those older men also “did their bit” bybecoming Air Raid Wardens, Auxiliary Firemen, SpecialConstables, or worked in the Civil Defenceorganisations. Others already in the fire service

or police carried out their duties admirably. ManySurrey Lodges arranged funds to help victims of airraids, or helped to buy Spitfire aeroplanes and otherarmaments.These storyboards tell of some of the stories of menand women who served our country. They were not allheroes, many were just ordinary people who put theircountry before themselves and were united for thecommon good. Values that are so entwined inFreemasonry. Whatever their contribution, we owe adebt of gratitude to them. We hope you can appreciateall that was done by them so that we can now enjoy ourlives in a peaceful democracy.As a mark of respect for those who fell in the GreatWar, Second World War, and other theatres of war, weare supporting and donating to the CommonwealthWar Graves Commission so that they may be able tocontinue the good work they do in tending the gravesand memorials to those who made the supremesacrifice.We owe a huge debt of gratitude to the author anddriving force behind the production of these displayboards – W.Bro. Peter Cartwright. He has spent manymany hours researching and compiling the fascinatinginformation contained here. These boards are a fittingtestimony to the courage and dedication of the peopleof this country, especially those who were Freemasonsin Surrey and south London. In addition, I must alsothank W.Bro. Nick Gras, who has led this project andensured as many people as possible across Surrey havethe opportunity of enjoying this display.

Ian ChandlerProvincial Grand Master

75 years ago theyrejoiced

WORLD WAR TWOSURREY FREEMASONS

The Indomitable spiritof Britain’s greatest generation

1 SURREY FREEMASONS

To them, our eternal thanks for giving us thefreedom to live our lives in a peaceful democracy.

This photographshows exhausted

AFS firemen in theforeground resting

after a night ofcarnage, whilst their

colleagues erect aunion flag, typifyingthe spirit of defiance

by our greatestgeneration.

WORLD WAR II produced a generation of people who some call ‘Our GreatestGeneration’. They lived admidst a time of great uncertainty. They were children

of the Great Depression, some who had lost fathers in the Great War of 1914-1918.Their families found even everyday living was a challenge. Yet they overcame hugeadversity, and went on to establish our modern world.

Can you imagine how difficult it could have been if their resolve had weakenedwith Britain facing invasion once our army had withdrawn from the beaches ofDunkirk? That indomitable spirit which eventually transformed their darkest hourinto their finest, became a defining moment in world history.

The early years of the war was a time when the whole population of the country,regardless of class or advantage, came together in a sense of shared purpose to opposethe extreme menace facing them. It would prove to be the biggest test of their lives.

SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

2 SURREY FREEMASONS

Surrey Freemasonsplayed their part in the Forces,Civil Defence and Home Guard

THE MASONIC PROVINCE OF SURREY is proud to have amongst them Freemasonsand their wives of the generation that served in the armed forces during World War

II, or who ‘did their bit’ on important war work. The members of Masonic Lodges didwhatever they could to ease the burden of serving soldiers, sailors or airmen. Funds wereset up to buy aircraft, armaments, and provide assistance to those whose homes had been

destroyed or damaged.Many of their members served in the forces in Europe, Africa and Asia. Some were Prisoners of War,

others suffered at the hands of the Japanese in Burma. Those at home volunteered and became membersof the Home Guard manning ack-ack guns,officiating at air-raid shelters, acting as Wardens,Firewatchers, helping in many Civil Defenceduties, becoming members of the SpecialConstabulary, or manning the pumps as AuxiliaryFiremen during the Blitz.

During the war many Masons who wereserving in the Civil Defence or Home Guardstarted new Lodges to replicate the camaraderiethey were experiencing. Many of these Lodgessurvive today and their current members are still,but in a different way, serving their localcommunities.

Just as important to the defence of ourhomeland were people living in the towns andcountryside, particularly women who worked inthe factories making armaments and essentialsupplies or those who volunteered for the LandArmy assisting our farmers to produce food.Young women whose invaluable service in theRAF, some working at Bletchley Park helping toeavesdrop on the enemy or tracking hostileaircraft on plotter boards at RAF stations.

Many people whether in the forces, working inthe factories, or caring for their families, facedgreat hardships. The war was to prove a valuabletest of their character.

Children – ‘The Forgotten Generation’ – theevacuees, young children and others a little older,who were sent away from London and theindustrialised cities and towns to escape thebombings. Some of their tales are quiteharrowing – of nights without their parents instrange unfamiliar places. They too showedcourage and determination.

We cannot cover all their stories on thesestoryboards, but we are at least acknowledging thepart they all played in giving our nation victoryover our enemies.

These storyboardshighlight some

of those people – ofheroism, of suffering, and

finally of joy.

SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to THE COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

DON PIRT, 95 years old, is a member of the CherchefelleLodge that meets at the Nutfield Masonic Centre, Redhill.

During the early part of the war years when Don was only 15years of age, he worked as a telegraph boy, a job he didn’t enjoy ashe often had to deliver bad news by telegram. When he reached 16years of age, he joined the Dorking Home Guard where he was theyoungest member with the oldest being 75 years of age. He says theBBC TV production of Dad’s Army brought home many memories.

On his 18th birthday in 1944, he received his ‘call-up papers’reporting to a barracks in Canterbury where he underwent physicaltraining before being posted to Suffolk where he learnt how to usea bren gun. It was back to Canterbury for the last part of his trainingincluding doing a 40 mile-and-back route march.

He was eventually posted overseas to Belgium to join the BlackWatch Regiment. He remembers Christmas morning when transportarrived to take them to the Ardennes to link up with the Americanswho had been fighting the Germans as they pushed through theArdennes Forest in what was known as the ‘Battle of the Bulge’.

Sometime later, he was given a 3-day pass to Brussels after restingin Mook, Holland. On returning the allies opened up with heavyartillery and he was ordered to march behind tanks into theReichwold Forest. They stayed in the forest for a few days duringwhich time they captured some German prisoners before moving toHassel, a large railway junction. It was there that a large number ofGerman prisoners were captured. His unit was ordered to prepare tocross the River Rhine. Moving further they met up with a mine-clearing unit. Don stepped on a mine, but luckily the mine wasprimed for heavy vehicles so it did not explode.

His unit moved into a farm only fora L/Cpl to spot an enemy patrol. Theyneeded to contact ‘B’ company, so Donran through an orchard to deliver themessage. But, in his words: “All hellbroke loose” when a German put a gunto his head as he was attempting toget through barbed wire.

He was taken away for interrogation during which time a Germanofficer wearing a monocle threatened him several times. Heeventually joined other prisoners including a British Warrant Officerand two American airmen who had both been shot down.

They eventually arrived at a place where there were hundreds ofBritish paras stretching down a narrow road for about a mile guardedby German soldiers [probably from the failed Pegasus Operation atArnhem Bridge]. After a short while they were loaded into cattletrucks for the journey to Fallingbostel Stalag IIb PoW camp.

On arrival they were given identification numbers and taken tohuts which were already full. There was supposed to be 50 to a hut,but when they arrived there were 250 to a hut. There was no cutleryor crockery and he had to find a tin on the rubbish dump which hecleaned off the rust with sand. They slept in their clothes and bootsotherwise they would have been stolen. Over the next few days therewere plenty of questions from those who had been there a few years.Reveille was at 6am and then they were counted. Breakfast at 6.30amwhere he got his tin filled with Erzatz coffee which we thought hadbeen made of acorns. It was a pretty horrible place as the toilets werecompletely unhealthy and some chaps got dysentry.

Luckily, Don and the camp were liberated by British GeneralMontgomery’s advancing army, and after a week Don was flownhome. He landed at Northolt aerodrome and was taken to a placenear High Wycombe where he had a shave and deloused. He said heremembers how lovely it was to have a shower and be given a newuniform. A little later he was given a pass for a 3-month leave.

Don’s war was not over yet though, as he was later posted toGermany and became a Military Policeman in the army ofoccupation. He stayed there for some time as the allies had dividedBerlin into sectors – British, American, French and Russian. It washis job to help keep the peace between the citizens of Berlin and theoccupying forces.

Don finally became a ‘civvie’ after he returned to the UK in 1946.

“ The first time you go into action youdon’t know what to expect, but after

that you are scared and shocked to seethe damage and bodies that are leftbehind. You soon forget about the

carnage and only think of looking out topreserve yourself and your mates ”

3 SURREY FREEMASONS

The wartime story of Don Pirt

Don meets theCountess of Wessex

Forced to eat grass!HARRY WINTER, Manor of Bensham Lodge No.7114.Now aged 98. Harry still attends Masonic meetings inSurrey.

During World War 2, Bro. Harry was a Flight RadioOperator Sergeant in the Royal Air Force – BomberCommand. He flew mostly inHalifax Bombers and wouldsometimes act as a relief pilotwhen aircraft needed to be flownover friendly territory.

His Halifax of Lion Squadronwas daubed on the fuselage withthe name of a well-known singer.His plane was shot down ona mission over Hamelin (German:Hamein) a town near the RiverWeser in Lower Saxony, Germanyin October 1943.

The pilot of the aircraft and two other crew memberswere killed by enemy fire, but Harry only sustained a fleshwound. Both the gunners of the aircraft was also killed, onetaking a shot to his head. “That memory is indeliblyengraved on my mind as I can still picture the traumaticscene”, said Harry. Luckily, he managed to parachute outof the burning aircraft and broke a femur on landing.

Harry’s luck continued when he was picked up by aGerman medical orderly who had saved Harry from beingshot by an armed German private. A Sergeant intervenedand Harry was taken prisoner.

The broken femur was repaired by the insertion of aplate which they then removed when the bone had healed.He said that the medical treatment he was given wassuperb and he couldn’t speak highly enough of the surgeon(who spoke fluent English).

On his recovery, he was moved to a PoW camp inPoland. This proved to be far less comfortable than thehospital. There was a general shortage of rations.

As the Russians advanced from the east in 1945, theGermans made the PoWs march to the perimeters of Berlinin what is known as the ‘Long March’ or more accuratelythe ‘Death March’. Hundreds of Allied PoWs died from thelack of food and drink. He remembers stopping near a farmwhen a sympathetic woman offered some food only forthere to be a mad rush which caused severe injury to thewoman. The Russians liberated the Allied PoWs but couldnot repatriate them immediately as they were being usedas a bargaining chip to secure the release of Russianprisoners in other sectors. Harry saw an opportunity toleave the misery and walked, crossing the River Elbe andinto the custody of the Americans.

FACT: The Long March, or so-calledDeath March started with 1,500prisoners, but only 800 survived. Therewas nothing to eat except grass at theside of the road, and it was very coldwith temperatures at -35 degrees.

Right British PoWs

SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to THE COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

From Private to Major –the story of Harold Pettinger

4 SURREY FREEMASONS

HAROLD PETTINGER MC, formerly of Bushey Park Lodge No.2381(Middlesex). This abridged account sent in by his son, W.Bro. Andrew

Pettinger of Woking Park Lodge No.6264 (Surrey).In September 1940, Harold Pettinger was instructed to report to the barracks

in Canterbury, home of the ‘Buffs’ (Royal West Kent Regiment) where he becamePrivate Pettinger. After medical examinations, inoculations and the issue of auniform, basic training followed including drill, rife range firing, bayonet practiceand route marches.

After arriving at Canterbury, Harold was sent to the War Office SelectionBoard which consisted of an interview and a written examination, and a little laterhe was advised that he had been selected for Officer training.

On completing his Officer training, Harold was Commissioned to the York andLancaster Regiment in Pontefract, Yorkshire. He was now a 2nd Lieutenant andgained the services of a Batman. A Commanding Officer ‘volunteered’ him forservices overseas and along with six other officers, he was posted to Egypt. Onarrival at Port Suez which had seen heavy bombing the regiment disembarkedfor the infantry base at Ismalia, close to the Suez Canal.

It was here that Harold was taken ill with tonsillitis and evacuated to Palestinespending a week recovering. His regiment had moved to Tobruk to relieveAustralian troops. He managed to get aboard a convoy ship that could only sailwhen there was no moon so that he and troops could land in the darkness butGerman Stukas were a constant menace as they sank one of the escort shipswhich meant he was delayed.

He was appointed ‘Officer commanding troops’ aboard aRoyal Navy destroyer which managed to reach Tobruk.Eventually he reported to the Battalion Adjutant and wasposted to a defensive concrete barrier known as ‘DalbySquare’. An artillery barrage had started, and assisted by theRoyal Tank Regt. they went ‘over the top’ and advancedtowards the German/Italian lines. They started to take heavycasualties, but luckily Harold and his troops kept behind atank until he saw an anti-tank gun emplacement near to theirobjective. He ordered four of his men to follow him wherethey shot two gunners. They managed to fight their waythrough to the trenches and captured thirty Italian prisoners.

Harold’s Corporal said “You are wounded Sir” as there wasblood on his back. He had sustained a shrapnel wound, and on inspection a bullethole was found in his respirator – luckily the bullet had missed his body. The unitheld ‘Dalby Square’ until they were told to withdraw back to occupy positionsastride the El Adem road. Later Harold’s Brigade were posted back to Egypt wherehe learned that he had been awarded an immediate Military Cross for the defenceof ‘Dalby Square’.

The Military Cross

Brother HaroldPettinger served inEgypt, Palestine,India and Burma.

Awarded theMilitary Cross.

Promoted toLieutenant, Captainand finally to Major.

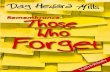

The full wartime story ofMajor Harold Pettinger,and many others can befound in the publication

wwaarr ssttoorriieesspublished by

W.Bro. Peter Cartwright,a Surrey Freemason,and is on sale nearby

at £10 per copy.All proceeds from this

book will be donated tothe Commonwealth

War Graves Commission.

Tobruk

Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

5 SURREY FREEMASONS

Jim never told his family until years after,that he had been awarded the Military Medal

JIM PAINE, M.M.Old England Lodge No.1790,Surrey.

It was many years after theending of the Second World Warwhen Jim Paine’s story was told.

It was when Jim and some of hisfamily went to Normandy, France tosee where he had landed in his tankat Gold Beach on D-Day on 6th June1944, that his secret was exposed. Hehad been entitled to a medal from theFrench Government for being at thelandings that helped liberate France.

To receive this medal, he had to register at a nearby centrerequiring him to give his rank, army number and other detailsincluding his award of the Military Medal. It was then that hisfamily finally found out about this military award that he had keptsecret for so long.

Jim had been conscripted into the army in October, 1939 andwith many other young men left Paddington Station on a train toPlymouth. It was here that they were trained in the discipline ofthe British army. He remembers the Regimental Sergeant Majorbooming: “You may break your mother’s heart, but you’re notgoing to break mine”, but before too long, Jim had been promotedto Lance Corporal and was in charge of a Bren Gun carrier. He wasposted to Scotland to undergo specialist training and at times didother duties including helping to rebuild war-damaged buildings

in London, training Home Guard personnel, andteaching soldiers to drive.

Jim’s love was mechanised armour, and hebecame a Squadron Sergeant in many different typesof tanks: the Crusader, the Churchill and theSherman.

When the British and Americans had broken out fromNormandy, Jim’s unit followed the army which liberated Paris.They drove onwards passing the ports of Calais and Boulognewhich were later captured, and into Belgium and Holland. TheGermans gallianty tried to push the allies back, known as the“Battle of the Bulge” in the Ardennes, but were unsuccessful.

During this time a German shell passed through his tank andthe tank became alight. He quickly took hold of the machine gunand fired it at the German forces allowing two of his crew toescape. The other two crew had been killed. Jim suffered an injuryto his back and was nursed secretly by a Dutch couple who heremained friends with for many years. It was month’s later that heheard the news that he had been awarded the Military Medal andlater promoted to Squadron Sergeant Major.

Jim had not wanted to tell his family about the award becauseJim just didn’t want to make a big fuss. He thought more of hismates than of a medal, but if it hadn’t been for a family member,his story would never have been told.Jim’s full story appears in War Stories available nearby.

“Their youth they gave,so others may enjoy theirs”.

Operation Market Garden KEN BARTON. St. John’s Lodge.Ken was born in 1923. He left school aged 16 to become

articled to a company in Wigan, Lancs. The war brought hisapprenticeship to an end as he volunteered to join the Armyin 1940, aged 17.

He was in the thick of the war being forward on the frontline where he became a ‘spotter’. He landed at Gold Beach onD-Day, 6th June and went on to serve in Belgium andeventually was part of ‘Operation Market Garden’ in the northof Holland.

Towards the end of the hostilities he was severelywounded by shrapnel which he carried in his body until theday he died in 2015.

FACTOperation Market Garden was a failed operation by the allies tocapture the bridges over the river Rhine, one at Arnhem, Holland,thereby enabling a bridgehead for the allies to extend into Germany.The operation was undertaken by the First Allied Airborne Army.Although the operation failed, it did liberate the towns of Nijmeganand Eindhoven.

SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

6 SURREY FREEMASONS

FACTThe largest sea-borne invasion in history saw the allies launch anattack on the beaches of Normandy, France. The Americans landedon beaches codenamed, Omaha and Utah while the British andCanadians assaulted the beaches codenamed Gold, Juno andSword. The Americans at first struggled to establish a footholdwhile the British and Canadians gradually moved inland. Theoperation was by no means easy as the German defences weretough to crack. However, by 12th July major gains had beensecured and the armies moved further into northern France.

FACTThe Dunkirk evacuation, code-named Operation Dynamo, is also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk. TheBritish Expeditionary Force along with the French and Belgian army were surrounded by the German armyin northern France between 26th May and 4th June, 1940.

Facing a potential disaster of evacuating hundreds of thousands of troops constantly menaced byGerman aircraft, Prime Minister Winston Churchill called for the British Navy to mobilise many civiliansmall craft in the south coast ports. These small boats proved an immense help as they were able to getinto shallow water and pick up the troops to either transport them to the larger ships or ferried themacross the channel to English ports with some craft bravely making return trips.

Over a period of 8 days, 338,226 British, French and Belgian troops had been evacuated from the beach.

D-Day, 6th June 1944JAMES HUMPHRIES. Egyptian Lodge No.27.A resident of Shannon Court, Royal MasonicBenevolent Home, Surrey.

Jim received the Legion d’Honneur from theFrench Government for his service in theNormandy Campaign. Jim joined the RoyalArmy Medical Corp Reserve and was called upto the regular army in September 1939.

As preparations for the invasion ofNormandy were made, Jim became a medicalorderly in Field Surgical Unit 37 and landed inNormandy on D-Day as part of the 2nd wave atLion-sur-Mer. His unit advanced throughFrance, Belgium and Holland. The unit attendedwounded French, British, as well as Germans and civilians.

DOUGLAS WINTER. A Surrey Freemason.Douglas recalls as a 20 year old dashing up the beaches in

Normandy on D-Day. He later served in Burma and Java.

DERRICK EDWARDS. Malden Lodge No.2875, Surrey.Derrick served in Palestine after being posted to France the

day after D-Day serving in the Welsh Guards Armoured (TankDivision). He was finally demobbed in 1946.

JOHN NICHOLS. A resident of James Terry Court, the RoyalMasonic Benevolent Home inSouth Croydon.

John’s son Andrew, a SurreyFreemason of The Lodge of ResolveNo.7177, supplied this account ofhis father’s experience duringD-Day.

John Nichols was born inMay 1925 in Greenwich. Hejoined the Royal Navy two weeksbefore his 17th birthday andserved on HMS Argonaut on D-Day as a gunner and helpeddestroy German on-shore gunbatteries. As a driver of a landingcraft he delivered troops andsupplies from ship-to-shore.

He remembers being told of the invasion plan with just fourhours to go and arriving in France to see, “all hell break loose”.He said: “I looked at the troops as they were going in andthought: how many of them are going to come back?”

John lost 65% of his hearing from the noise of explosionsduring the battle. He reflected: “I’ve come out of it with just halfof my hearing gone, but those poor devils, they lost their lives. Ithink of them all the time.”

The government of France awarded John the Chevalier de laLegion d’Honneur for his service in helping to liberate France onthe 6th June, 1944.

Top picture left column:Troops landing on a Normandy beachon D-Day.Bottom: Pleasure boat helping totransport troops away from the beachof Dunkirk.This column: The Legion d’Honneur,Chevalier Medal.Bottom: John Nichols.

The miracle that wasDunkirk

SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

ROY MILLER. StoneleighCoronation Lodge No.5699.Roy served with the RoyalNavy in South-East Asia from

1944. He said that VJ-Day [Victory over Japan]was always very emotional.

“It was an arduous campaign and it should beremembered for ever more,” he said.

Roy was a gunner on the aircraft carrier HMSIndomitable, helping to see off a number ofKamikaze attacks by Japanese planes.

“Kamikaze aircraft, we were warned aboutthem. We were told we had to shoot them downor we’d lose the ship. We were attacked three orfour times but we managed to fight them off,I believe we shot them down.”

He spent three years fighting during the warand was onboard with one of the warships whichtook the surrender of the Japanese in Hong Kong.

KEITH BELL. Surrey Lodge No.9167, Surrey.Keith was a young sailor in the Royal Navy’s Arctic Convoy runs. Keith remembers his ship covered in

2 ft. of ice ploughing through icy storms to deliver needed arms and equipment to the Russians. He is aholder of the Arctic Star.

DENNIS SEIGNOT. Fernhamme Lodge No.9149, Surrey.Dennis received the Arctic Star and Ushakov Medal for the hazardous trips to help the Russians.

RAY FULLER. Bisley Lodge No.2317, Surrey.Ray served aboard HMS Illustrious, an aircraft carrier in the Far East from 1943 to 1945. Arctic Star Ushakov Medal

The war at sea . . .

Kamikaze attack on HMS Indomitable

FACTOne of the worst jobs in the Royal Navy or Merchant Navy was to be onboard aship during the Arctic Convoy runs. These were ships destined for sea ports loadedwith badly-needed armaments and supplies for our Russian allies.

Very often the journeys took place in dangerous seas especially during thewinter months when ice over 2 ft thick covered the decks.

Around 1,400 merchant ships left British ports under the Soviet Union’s Lend-Lease programme. Eighty-five merchant vessels and sixteen Royal Navy warshipswere lost. Over 3,000 sailors lost their lives.

And in the airE. HOOKINGS. H. A. Mann Lodge No.7493, Surrey.

Bro. Hookings joined the RAF in 1940 at the age of 20. Hebecame a Bomber Pilot in 1944 and was shot down and capturedand spent the rest of the war in Stalagluft 4 PoW. camp.

TONY BRANDRETH. Tiffinians Lodge No.3530, Surrey.Tony was stationed in the RAF in France and was

Commissioned as a Flight Lieutenant. He returned to civilianlife in 1946.

LEN MAJOR. Waddon Lodge No.4162, Surrey.Len served in the RAF from 1942 to 1945.

JOHN WADIA. Former resident of a Masonic RMBI Home.John was born in Bournemouth in 1920 and left school when he turned 15 years old. In 1942, he joined the RAF as a Flight Engineer

for 578 Squadron. He primarily flew in a Halifax Bomber aeroplane which was nicknamed ‘Leeping Lena’. His role was to sit behind thepilot and keep all four engines running during the flight. His Squadron flew thirty-eight operations during the war.

He then moved to 77 Squadron and towards the end of the war was flying back and forth across the Atlantic ferrying American VIPpassengers and cargo. The most important was US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt who flew with him on a number of occasions. “Hewas a very down-to-earth and quite a nice person”, said John.

7 SURREY FREEMASONS

A Halifax Bomber

SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

The ‘forgotten generation’Children who stayed at home during the war saw normal family life disrupted. Forsome children, those who were evacuated, it was, just a great adventure – somethingthey had to do because all the grown-ups said they had to do it. They weren’t allfrightened or fearful – in fact for many of them it was a bit of a holiday. But forsome it was a traumatic and horrible experience, especially when being lined up ina strange school hall and ‘chosen’ like they were a piece of second-hand baggage.Here are a few stories of people who are now in their mid-to-late eighties andnineties, but can still recall the impact it had on their young lives.

KEN COOK. A Surrey Freemason. Ken was just 6 years old in 1939, and recalls the Blitz and the heavy bombings. He says thatbefore his family received the Morrison shelter, he slept in acupboard under the stairs. One night he dashed out of bed andran into his mum’s room and hid under the bedclothes. Therewas an almighty explosion. The next morning he went into hisroom to find a huge lump of masonry had landed on his pillow.Croydon, he said, was badly hit by V1 flying bombs. Onemorning at school a very solemn headmaster read out thenames of children who had been killed the night before inWindmill Road, Croydon. “Later the advanced V2 rocketbrought morale to a very low”, he said.

“You will hear people from London talk about the six months ‘phoney war’,where nothing happened, but on the South Coast it was a different matter,being less than 50 miles from the German-occupied airfields in France.

The German fighters would regularly strafe along our coastline and bombthe railway works. The only defence at that time was a group of soldiers withrifles firing from the Ice Cream Parlour” – An Evacuee.

MRS MAUREEN BLAKEY. The wife of W.Bro. George Blakey, Seaford Lodge No.2907.She was one of the first schoolchildren over the age of five to be evacuated with their schools. The

under fives were evacuated with a parent and advised by the government to go as far away fromLondon as they could manage, hopefully with family relations, or they would be found somewhere tostay by order of the government.

Normally, the countryside is a safe haven, but even moving to an idyllic country village posed athreat to the insecurity of young minds.

Some children had never seen a cow or horse or even chickens running freely. Everything to themwas strange and these children’s lives changed dramatically and were never to be the same again.

The evacuation, codenamed “Pied Piper” was not restricted to London and many other towns andports also sent their children to safety. In all, some 3,500,000 young children were evacuated.

CHARLES NELSON DENCH. Paxton Lodge No.1686.Born in 1931, Charles aged 8, remembers on 3rd September, 1939 children and teachers from the

Woodland Road School, Upper Norwood being put on a train at Gipsy Hill Station, to be evacuated.He says:

“We were given, a gas mask, an apple, and orange, some sweets and a tin of Corned Beef. We alsohad a card with our name on it, tied around our necks. As the train departed, we waved to our parents,perhaps never to be seen again, and in time arrived at Lancing Station in Sussex”.

WILLIAM STERN. Thurlow Park Lodge No.5476, Surrey.As an evacuee, Bill Stern in the early part of the war joined the 1st

Wokingham Scout Troop. Since then, Bill has been a member of thescout movement for over 70 years.

The Scouts did atremendous amount ofvoluntary work duringthe war years. Theyacted as stretcherbearers, helped in firstaid, helped to repairbuildings and did manyother useful jobs forthe community.

ERIC ALLEN. Old Palace LodgeNo.7173, Surrey.

Eric who was born inPortsmouth, was 6 years old in1941 when Portsmouth was hitby its first blitz. Some 170 werekilled, over 400 suffered majorinjuries and many streets weretotally demolished on January10th. There were over 300raiders dropping incendiariesand high explosive bombs.Eric’s house was flattened, andhe was trapped overnight andhad to wait to be rescued. Hewas billeted along with othersin a school hall. “The Germans”,he said, “were trying to destroyour naval fleet in Portsmouthdockyard”.

At this stage of the warpetrol was rationed and onlyavailable with coupons. Thesewere for important usage,available through the war office.Somehow my Uncle managed toobtain the use of a lorry andmoved what was left in the wayof furniture and our belongings.

SURREY FREEMASONS

Children who stayed at home during the war saw normal family life disrupted. Forsome children, those who were evacuated, it was, just a great adventure – somethingthey had to do because all the grown-ups said they had to do it. They weren’t allfrightened or fearful – in fact for many of them it was a bit of a holiday. But forsome it was a traumatic and horrible experience, especially when being lined upin a strange school hall and ‘chosen’ like they were a piece of second-hand baggage.Here are a few stories of people who are now in their mid-to-late eighties and

nineties, but can still recall the impact it had on their young lives.

SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

“In Defence of the People” – Menof Kingston and Surbiton formedMasonic Lodges during the war toreplicate the camaraderie theywere experiencing whilst serving inthe Civil Defence as Wardens,Firefighters, Special Policemen ormembers of the Home Guard.

A new Masonic Lodge was formed in July 1941 witha Lodge motto of Pro Civium Salute (In Defence ofthe People).

One of the great changes that the War broughtwas the growth of communal interest anddependence; many who had previously beenstrangers to each other found themselves in closeassociation and with a common interest. This wasparticularly so in the the Air Raid PrecautionaryService. During the evening period, wardenspatrolled the blacked-out streets, or on duty in thenarrow confines of the Warden Posts, formed closefriendships.

Men, some of whom were Freemasons belongingto Lodges in the area, served at the Air Raid Warden’s Postknown as K.16 which stood on what is now the garden ofthe junction of Ellerton and Ditton Roads, Surbiton.During period of quietness they began talking about howthey could continue the camaraderie they had establishedoutside their duties as Wardens. Those men who were notMasons began to realise that Freemasonry was a force forgood and joined with their Mason colleagues in establishing a new Masonic Lodge. They had originallyvolunteered in the Civil Defence for the purpose of alleviating suffering and bringing relief andprotection to their fellow men, echoing the principles so firmly entwined in Freemasonry.

The first name of the Lodge suggested was Surbiton Civil Defence Lodge, but was laterchanged to Elmbridge Lodge being thename of the local telephone exchange.The Elmbridge Lodge came into beingfounded on their service to the defenceof the people, and today, 79 years later,Elmbridge Lodge is still serving the localcommunity.

In the photo on the left is Bro. SimonJakeman (centred), a local Firefighter anda member of Elmbridge Lodge whoreceived the British Empire Medal.

SURREY FREEMASONS SURREY FREEMASONS supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

1 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

SSuurrrreeyy FFrreeeemmaassoonnss aannddA E R O P L A N E SThere’s a proud history in Surrey when it comes to aeroplanesas not only did we have the very first international airport inCroydon, but two of our Lodges had within their ranksoutstanding aeronautical and design engineers. The most iconic of all aeroplanes is the Supermarine Spitfire, madefamous with its sister fighter, the Hawker Hurricane being the aircraft that our airmenused to fight so galliantly in defeating the German Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain.

A Founder member of the Lodge of Harmony and Progress, W.Bro. George Nicholas was instrumental inhelping to further the record-breaking Supermarine Spitfire. The credit for designing the aircraft rightlybelongs to R. J. Mitchell, CBE, FRAeS (1895-1937) (pictured right), but George played an important partin the aircraft’s development. It was in 1931 when George started to work in the design office of VickersArmstrong (Supermarine) Company, in fact his letter of appointment from R. J. Mitchell is now in theMuseum of Aviation in Southampton. The aircraft had won the Schneider Trophy races in 1927, 1929,and 1931 and it was George’s job as a Stressman to test for pressure on the wings. During hisemployment George studied at University and gained a professional qualification for the Institute ofAeronautical Engineers. Whilst at home in Southampton, George and his wife Edith suffered bombdamage during the intensive Blitz on the Supermarine Design Office in September 1940. He saidthat a bomb had dropped onto the office but thankfully it didn’t explode and rolled along the officefloor finishing up in the mud of the River Itchen below, but his home feared much worse.When the Supermarine office closed in 1957, George moved to the Vickers Armstrong’sBrooklands Works at Weybridge, Surrey, and in 1958 his family moved to West Byfleet. Georgecontinued with his Freemasonry, following in the footsteps of his father, and grandfather.George’s son Eric, is a Freemason in the same Lodge, continuing the family tradition.

THE KINGSTON AERO LODGEIn 1918 a Masonic Lodge was formed from men who were working at the Sopwith Aviation Company. Pioneer aircraftdeveloper and manufacturer, Tommy Sopwith and his partner Fred Silgrist, who was regarded as a brilliant aeronautical

engineer, tested and built many types of aeroplane. The most famousof these was the Sopwith Camel which flew in the Great War of1914–1918. Working from an old disused skating rink in Kingston-upon-Thames, Tommy and Fred went on to employ many thousandsof people in their Canbury Road Works in Ham.Fred Silgrist became a member of the Kingston Aero Lodge whosemembers mainly worked in the aircraft industry around Kingston-

upon-Thames. Although Tommy never became a member, he would oftenjoin in the Lodge’s social functions such as Ladies’ Nights and was particularly

genereous in donating sums of money to theRoyal Naval Air Service Comfort Fund, a charity to

which the Lodge was a contributor. The Lodge alsoattracted engineers from around Surrey like Harold Birdsall Bullingham, theinventor of the Zendik Cyclecar.The Ham factory (of 38 acres) was sold to Leyland Motors and the newly-formedH. G. Hawker Engineering Company which was a forerunner of the Hawker SiddeleyCompany, the developer and manufacturer of yet another WW2 fighter aircraft, theHawker Hurricane.The greatest claim to fame in the Lodge though, must be Bro. Arthur WhittenBrown (later Sir) (1886–1948). He and pilot John Alcock were the first to fly acrossthe Atlantic from St. John’s, Newfoundland to Clifden Connemara, Ireland whichtook place on 14th June, 1919.During World War II, Sir Arthur Whitten Brown served in the Home Guard as aLieutenant-Colonel before resigning his commission in July 1941, to rejoin theR.A.F. to train navigators.

Sir Arthur Whitten Brown

Hawker Hurricane

Supermarine Spitfire

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

2 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

SSuurrrreeyy FFrreeeemmaassoonnss aannddF I R E E N G I N E S

WORLD WAR TWO

1940sFIREMEN

2020 FIRE ENGINE

Through late 1939 and into 1940, men ofqualifying age were called-up to join thearmed services. Some though were alreadyserving in the National Fire Service. Onesuch man who was a Freemason from aLodge that met at the Camberwell MasonicHall, south-east London, was BrotherAlbert Sams.At the age of 24, Albertfollowed his Uncle Fred’sadvice, who was in the sameMasonic Lodge, to join theNational Fire Service. So inMay 1940, Albert became atrainee Fireman at the RoyalArsenal, Woolwich.His training barely startedwhen he was thrown intothe front line of firefighting.The German Luftwaffe hadstarted bombing the LondonDocks and Albert, night afternight, helped his colleaguesextinguish fires and dealingwith buildings that were ina state of collapse. Thedangers he faced were verysevere, not only from theterrible heat from the firesthey were fighting, butfrom unexploded bombsand fractured gas mains.Many a good fireman lost hislife or was badly injured. Thecamaraderie in the fire servicewas beyond praise as eachfireman would do their utmostto help a colleague in times ofdistress, not unlike theprinciples we enjoy in Masonry.Albert’s Lodge donated sumsof money to the WoolwichFire Station to assist the wives offireman who had been badly injured orhad died. Thankfully, Albert althoughsuffering from smoke inhalation whichaffected him for periods during his life,came through the war without seriousinjury. In December 1945, he receiveda letter (above) from the RoyalArsenal Woolwich thanking him forhis valuable service.In 1951, Albert became theWorshipful Master of his Masonic Lodge.

Recently Freemasons have donated £2.5 million topurchase two brand new fire engines.This engine’s ladder platform reaches an incredible64m, making it the tallest in Europe. In addition tothe two units, Freemasons have funded six fastresponse outlander vehicles and four bariatricstretchers.

CONTINUING FROM THE LIFE-SAVING WORK IN 1940 TOLIFE-SAVING IN 2020

SURREY FREEMASONS

3 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

Quite a momentous day for thisSurrey Freemason

From the diary of W.Bro. H. Earle,Bookham Lodge, Leatherhead.Sunday, 15th September, 1940.“I was spending the day with myfamily at a famous beautyspot overlooking the weald of Surreyand Kent. I’d taken some well-earned rest from my duties asSecretary of my Masonic Lodgepreparing for our next meeting, andin the civil defence where my dutiesinvolved spotting enemy aircraft.My wife had packed a picnic and mytwo boys had brought the cricketbat, ball and stumps, and we were alllooking forward to an enjoyable day.The whole panorama of thebeautiful Surrey countryside is

before one, and it was here that we were about topartake of our lunch. But very shortly the enemybombers were heard high up above in close-packedformation.Anti-aircraft batteries opened fire immediately, andthe sky seemed full of fighter aircraft going up inpursuit. My family and I seated ourselves with ourbacks to a large beech tree, as I thought this affordedthe best protection under the circumstances. In afew seconds a large German bomber hurled out ofthe sky like a falling leaf. The pilot managed toregain some control when near the earth and itseemed as if a safe landing might have beenpossible, but he made a sudden dive, hitting theground, and the machine immediately burst into aninferno of flame and smoke. It was a terrible scene,taking place just down below us in the valley inbroad daylight, This, by the way, was the only timemy youngest son showed any sign of distress. Ourfighters were zooming in all directions and we couldhear the rattle of machine-gun fire above us.A big black German bomber planed right acrossour vision about 300 ft from the earth, and withengines off, obviously trying to land, when to ouramazement there was a burst of machine-gun fire ashe scraped over the roof of a farmhouse very near toa golf course. It was astonishing to us that theoccupants of the machine in such a perilous positioncould still machine-gun a farmhouse as they passedover the roof and pancaked into a field half a milefurther along apparently undamaged. We were toldby someone who was near the field that the machinewas a Dornier. While this was going on anti-aircraftbatteries were sending up shells at a terrific rate.Shells were bursting in a wood behind us, and we felt

that at any moment some splinters might descend upon us. Aftera very short interval we saw a formation of Spitfires bring downtwo more bombers on the distant hills.It was then that my wife pointed out to me one of our fightersthat was obviously in difficulties. He was spiralling towards earthand his destruction seemed imminent when, much to our reliefand amazement, he realised that he was going to hit the ground.At the top of a vertical climb the parachute opened and the pilotfell our of the machine and landed safely. As he dropped, hismachine fell to the ground like a stone.Then a group of German bombers, hotly pursued by our fighters,were seen making their way, as best they could, to the coast.I looked at my watch; the action had lasted thirty-five minutes.Our tense nerves relaxed. It was then we began to realise theperilous position we had been in. What we had witnessed wasthe Battle of Britain. We had seen with admiration the wonderfulfighting quality of our fighter pilots. The Surrey countryside waspeaceful once again, and the only evidence of the battle was thesmoking ruins of the German bombers in the fields below us.After that we tucked into our lunch and played a game of cricket,with my eldest son bowling me out for a duck. Just after sixo’clock we arrived home, to find that a bomb had dropped sixdoors away from our house, shattering many of our windows andsending roof tiles flying in all directions. All-in-all, quite amomentous day”.

The Surrey countryside with a superimposed photograph of thevapour trails of aircraft during the Battle of Britain.

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

4 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

Tobruk

Mason’s wife tells of hertime in the WAAF ‘plotting’The story of Helen Mills, the wife of W.Bro. Geoffrey Mills of Old Wokians Lodge andNoel Money Lodge, Surrey.

“I was born in Walton-on-Thames, Surrey where I went toschool and then to Wimbledon High School.In my home town of Weybridge, I was a member of theWomen’s Junior Air Corp and was given lectures and drillby a former Sergeant-Major who served in the First WorldWar. The Corp was the forerunner of the Air TransportAuxiliary whose members, although not allowed to docombat flying, ferried Lancaster, Spitfire and Mosquitoaircraft from the factories to the R.A.F. airfields.

I joined up in 1942 in Kingsway,London as a volunteer in theWomen’s Auxiliary Air Force(WAAF) and was sent toBridgenorth for kitting-up.After three weeks training ata rather damp Morecambe onthe Lancashire coast inAugust, I was posted toHornchurch, a FighterCommand Airfield in Essex.As a volunteer, I choseClerk (Special Duties)whose qualifications were

to be mentally alert and accurate. More important than high

educational qualifications were intelligence, calmness andquickness of uptake.When the station closed in 1943, I was posted to No.11Group Uxbridge as a ‘Plotter’ down a bunker. Plottingentailed putting arrows and indicators on an OperationsTable which was a large map, in this instance of the south-east of England, the English Channel and the coasts ofFrance, Belgium and Holland. Other Groups, 10, 12 and 13covered the rest of the country. Information from Radar‘blips’ all around the cost were sent to Bentley Priory,Stanmore, headquarters of Fighter Command where theywere translated into ‘plots’, i.e. arrows.In the Battle of Britain, plotters used wooden-typecroupier sticks and pushed plastic arrows; a difficult task. Iused magnetic sticks which placed the arrows until it wasplaced and then it retracted when the lever on the handlewas released and the plot placed. The informationregarding a raid was relayed on the tote board above themap. Timing of the plots was done at five minute intervals,measured by three colours, red, yellow and blue, so that asthe aircraft were moving, the colour of the plot wouldindicate the timing. There were only ever two colours on atany one time, so that, as the next five minutes came, thecoloured arrows of fifteen minutes previously wereremoved. There were four watches covering a 24 hourperiod, and the Operations Room was continually mannedwith only one plotter at the table at any one time. I spentan hour on plotting, but if there was a blitz on the plots,

i.e. that’s if the plots were coming through fast,concentration started to go. It was better to ask to berelieved and let someone else take over than make amistake. In bad weather when there was no flying, so Icould take a rest and enjoy a cup of tea. No smoking wasallowed in the room, even for Winston Churchill. TheNo.11 Bunker was 60 ft. down underground with 76concrete steps to climb and descend – there was no lift.After a night’s duty, it seemed a mountainous climb.The activities and movement of aircraft coming or leavingan airfield such as Hornchurch had to be passed to theOperations Room and be recorded in notebooks usually byan Officer. In the early days the plight of the aircrews weretannoyed to the Operations Room, but as it was thought tobe too harrowing, this was discontinued. When the V1sstarted to invade our skies they were plotted and manywere blown apart in the air, but unfortunately V2s beingrockets were far too fast to be plotted.Accommodation for the WAAFs was in an old airman’smarried quarters with usually eight to a house. We had anold Baxi boiler which provided heat and we could make ourown tea and toast. Our beds where basic metal with a horsehair mattress.On the 5th June, 1944 (the day before D-Day) I went onduty in the evening when Squadrons were starting theirsortes for the big day. The Operations Room was markedout for the ‘Operation Overlord’ landings. All Allied forceswho had camped in the acres around Uxbridge Stationbegan to disappear over the channel to face the enemy atthe ‘Second Front”.Helen after being transferred to R.A.F. Records atGloucester, was demobbed in 1946. She later trained as ateacher, got married and had children.

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

This painting entitled A View of Box Hill, Surreyby George Lambert painted in 1733 is ondisplay at the Tate Gallery, London. It typifiesa part of Surrey regarded as an area ofoutstanding natural beauty.Two hundred and seven years later though in1940 it was to become a vital defence against apossible German invasion. The peaceful andtranquil setting was to house ack-ack guns,searchlights, concrete pill boxes, and tank traps.Throughout history the area around Box Hill, inthe valley of the River Mole known as the MoleGap Escarpment has been identified as apossible route for an invading army from thesouth coast on its way to London. If AdolfHitler’s army had successfully raided ourshores, the front line would have been drawnalong the North Downs Escarpment. This laststop gap, called the General Headquarters LineB, ran along the North Downs from Farnhamvia Guildford to Dorking, before following theriver to Horley. It would have had the Britisharmy stubbonly defending the route to London.If London had fallen the rest of the countrywould have surely followed.Even in Victorian times the strategic positionof Box Hill was recognised. A fort can still beseen on the summit. Box Hill was mostprobably used by the Romans and later in thereign of Queen Elizabeth I as a beaconsignalling post. No doubt London would havebeen warned of the Spanish Armada by a chainof beacons from the south coast to Londonwith Box Hill being one.Because of its elevation (735 ft./224 m) it isideal for the placing of radio masts whichadorn its summit, although out of view in theclump of trees. In 1940, it would have beenideal for the spotting of enemy aircraftapproaching from the coast from airfields inFrance and the placement of anti-aircraft guns.

The Masons of Box Hill Lodgemanned the ack-ack guns andsearchlightsFreemasons from Lodges in the Dorking and Reigate area, formedthe Box Hill Lodge in 1943. Some were also members of the localHome Guard Battalion and Civil Defence organisations.The photo here, shows the Lodge members proudly posing for aFounders photographin 1943 with Box Hillin the distance.The bottom photoshows men of a SurreyHome Guard Battalion.Notice that some arewearing ribbons fromservice in the GreatWar of 1914–1918.

Superimposed picture showingGerman aircraft over Box Hill.

Bottom: Searchlight trails

5 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

Dig for BritainThe Provincial Grand Master of Surrey Freemasons,Ian Chandler likes nothing better than to go diggingaround his allotment when he has finished with hisduties of leading Surrey’s Freemasons. His allotmentin Caterham which he regularly tends andcultivates, gives him a regular supply of potatoes,green vegetables and fruit.If he’d been living during WW2, he most certainly would have been producing food to helpwith the shortages caused by the war. “Digging for Britain” was the headline on posters produced by the Ministry of Food to encourage people to plant fruitand vegetables in their back gardens and in their allotments.

Early on in WW2, Britain faced a growing crisis. TheGerman navy had been using surface raiders like thepocket battleship, Admiral Graf Spee and U-Boats to attackshipping in the Atlantic and the Indian Oceans. Hundredsof thousands of tons of ships had been sunk and manymerchant sailors lost their lives.The British Admiralty which commanded the largest navalforces in the world was deeply worried on how to preventthe attacks. Air cover for ships was only useful if they werewithin flying distance of the mainland.When the German army marched into France, sea ports onthe English Channel, and the Bay of Biscay facing theAtlantic Ocean became available for the building ofsubmarine bases. With the implementation of these, theU-Boats could reach further out into the Atlantic and enterthe Mediterranean to pluck off merchant ships coming from the Suez Canal. The Admiralty devise the “Convoy Strategy”by which British naval vessels escorted the merchantmen, but U-Boat attacks continued at an alarming rate.Meanwhile, food and commodity shortages were having a deep effect on civilian life. If we could notstop the daily loss of shipping, the prospect of Britain starving was a real threat. The Ministry ofFood sought to educate people on how to save food including waste scraps which could be fed

to farm animals. Poster after poster appeared on publicbuildings, in cinemas, and everywhere else where theycould be hung. They advised on the best ways to cookfood, how to use available ingredients better, and how toavoid waste.Leaflets were issued advising on the best way to grow food inback gardens or on allotments (see left).Farms and small holdings had a serious shortage ofworkers as traditional male farm workers had beenconscripted into the forces. The Women’s Land Armydid a stirring job in helping to keep up the supplyof food.As the war progressed so did theamount of British peopleestablishing allotments and by thetime victory came in 1945 there were1,300,000 allotments in the U.K.Allotments are as popular today, as they

were in wartime, just ask RW.Bro. Ian Chandler on thebenefits of having an allotment.

Dodge the doodlebugs whilst gathering the beans

WORLD WAR TWO

6 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

SURREY FREEMASONS

As a young lad of 7, living in Ewell when war broke out in September 1939, my firstthought was will I still be able to receive my favourite comics. Every week I used towait for the newsagent’s delivery boy to pop through the letterbox a copy of TheHotspur. I used to love reading the Hotspur mainly because my uncle playeda few times for Tottenham Hotspur the north London football club although thecomic had nothing to do with football, but it was in fact full of exciting stories withsome good illustrations. A lot of the stories were about schoolboys who had becomesoldiers in the First World War who’d won medals by doing brave deeds. Sometimesthere were some crime mysteries where schoolboys solved the crime and caught thecriminals, but above all it was just a damn good read. It was the only thing that kept mequiet, said my mum.One Thursday in March, 1941 I was annoyed that my comic hadn’t been delivered. Ipaced up and down and kept looking out of the window for the boy on his bicyclewho normally had a large canvas bag hung around his neck with the words SundayDespatch printed on the front, but there was no sign of him. Later my mum went tothe shops to get some groceries and on her return she said that the newsagent’sshop had received a direct hit from a ‘doodlebug’ and that the newsagent Mr. Johnsand his wife, had been killed. Very sad, poor old Mr. Johns, he always gave me asweet when I came into the shop with my dad.I never really thought about who wrote the stories in my comics or where it wasprinted. All I knew was that 2d was taken out of my pocket money to pay for it.Dad insisted that I should learn about the value of money, and that it didn’tgrow on trees. He made me do a ledger of how I spent my pocket money. Funnilyenough it put me in good stead in later life when I trained to be an accountant, and then later when Ibecame the Treasurer of my Masonic Lodge which met in Camberley. But in 1942, I began to question about thecomic’s production. In our regular daily newspaper The Sketch, it reported on the loss of British shipping by enemy shipsand submarines. I sort of cottoned-on when my mum said that much of our paper before the war had been imported fromoverseas from Canada, the U.S.A. and Sweden, and that it was now a valuable commodity when you consider just howmany British seamen risked their lives daily to bring it to our ports. It made me think how lucky I was to be reading mycomic, and I prayed to God to ask Him to protect our sailors.Many years later, and much older, I researched into the popularity of comics during the war years. Did you know that theowners of The Hotspur, D. C. Thomson & Co. sold 350,000 copies of the comic and a million copies together with sister itspublications Red Circle School, The Gem and The Magnet? Altogether comics and similar publications sold over three million

copies per week in the U.K. Comics were big business in those days, unlike today wherechildren are mostly interested in computer games.In 1943, there were so many more stories about the war than earlier in 1939. You can seefrom the illustration of The Hotspur (above) or the Adventure (left) both from 1943, thatboys could imagine what war was like by looking at the front cover of the comics. Thewriters of these comics did tend to glorify the stories they portrayed, understandably Isuppose, because how could they tell the truth about British soldiers, sailors andairmen dying, of us losing battles at sea, in the desert of north Africa, or being treatedinhumanly by the Japanese army in the jungles of Burma? No, it would not have soldthe comics – who wants to read about doom and gloom? However, what it did portrayto youngsters like myself was that going to war and wearing a uniform was anhonourable thing to do, but comics did glorify the war.There was a great deal of propaganda during the war years and in particular inGermany. Dr Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda Minister, was a master of it. Hismanipulation of the German press and radio persuaded German citizens that HerrHitler and his Nazi party were the saviours of Germany. He installed William Joyce,or commonly known by the British public as Lord Haw Haw, a British traitor, tobroadcast daily to the British public that Britain and her Empire were losing the war in an effort to undermine the British people’s morale.

Both sides used propaganda, and it played an important part in bolstering or destroying morale. Thankfully, truth always wins, but the comics did play their part in keeping up morale in the

young – to instill in us a sense of pride, a love of our country, a will to win through, and to defeat tyranny.

I was annoyed when ournewsagent in Ewell didn’t deliver my comic!Surrey Freemason tells his story

7 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

Many Masonic Lodges during the Second World War,allowed members to wear their uniforms if they could notwear their usual regalia at meetings. One Lodge – CovehamLodge which usually met at the Parish Rooms, Cobham hadto move to the New Bull Hotel, Leatherhead at the start ofthe war as their building was to be used for civic functionsand as a rest centre for men in the Civil Defenceorganisations.The Lodge Secretary never knew precisely who was goingto attend the Lodge meetings. Some of the members whowere on active service did their best to attend if they werelocal, but some others had no chance of attendingmeetings if they have been posted abroad. The Lodge had amixture of men serving in the forces, and some older menwere serving in the Home Guard or Civil Defenceorganisations. Uniforms of one sort or another dominatedthe Lodge room.One Worshipful Brother, Ian Pearce was a Colour Sergeantin the Parachute Regiment. Bro. Pearce missed severalmeetings as he was involved in the parachute landings nearPegasus Bridge (portrayed in the film A Bridge Too Far). Hewas also involved in the Normandy landings being in thesecond wave. Other members were onboard ships, serving

in the Royal Engineers, they had a gunnery technician inthe Pathfinder Corp, a corporal in the Army Catering Corp,a private in the Royal Signals Corp, a lance-corporalserving in the R.A.F., and even a clerk working behind adesk at the war office. Uniforms varied from army khaki,the blue and white of the senior service, or the blue of theR.A.F. Not forgetting the uniforms of some older men whohad joined the Civil Defence units as Wardens or in theCivil Defence Rescue. Ironically, one member who was anAir-Raid Warden at a Civil Defence Post in Dorking, wasactually the Lodge’s Junior Warden. For those unfamiliarwith Masonic Lodge Officers, the Worshipful Master of aLodge is senior to the Senior Warden and Junior Warden.Another member, W.Bro. Brian Powell who had beentraining pilots as an instructor was seconded to fly LordBeaverbrook as his personal pilot. On a number ofoccasions W.Bro. Powell flew with Winston Churchill.

It was a sad time when Bro. Philip Chase lost his wife andtwo children in a local air-raid, but members rallied roundto support him in his grief. Such was the comradeship withall the members. Whenever or wherever possible, Lodgemembers would help a Brother in times of distress –principles that are so entwined in Freemasonry.

WORLD WAR TWOMen from Cobham and Leatherheadunited in the defence of the nation

8 SURREY FREEMASONS

Supporting and donating to theCOMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

SURREY FREEMASONS

WOKING FREEMASON DESCRIBESCONDITIONS ABOARD LONDONLANDMARK HMS BELFAST ONTHE CONVOY RUNS TO RUSSIA

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

BRO. HARRY FOXTON, a resident of Woking and a member of a Lodgemeeting in Farnham joined the Royal Navy in 1942 and describes whatlife was like aboard a convoy ship.“Tough, bloody tough! I didn’t realise what life was like on board a shipuntil I stepped onto the gangplank of my first ship docked in Portsmouth,HMS Belfast – a Light Cruiser.At first it seemed okay. Most of the blokes were like me, a bit apprehensiveof what to expect. We all knew from school about the glories of the RoyalNavy – Nelson and Trafalgar and that sort of stuff, and the floggings aboardwooden warships. But this was different. This ship was all metal, a rathersickly grey colour going rusty in places, but a fine ship at that. She’d beenrecently repaired and underwent a refit after she struck a mine in 1939.After a time we got used to the routine and the Officers weren’t that bad.Sometimes they’d come down and share a joke, but it was the PettyOfficers who were the scourge. You had to be on your toes when they wereabout. One of them came from Woking, so it made things a little easierwhen he and I were on duty together as he knew my cousin, but all thesame he could dish it out when he wanted to.After a month cruising – no don’t get it wrong, this cruising was much,much different to what I experienced on my 60th birthday cruising aroundthe Caribbean in 1984. This cruising was bloody hard work, no stewards tobring you cocktails by the pool, no club sandwiches whilst placing a chip atthe roulette wheel. This cruising was up the north west coast of Britain andaround the Arctic Sea, south of Iceland, and consisted of practice for battle.If we fired our guns once, we fired them a hundred times and we had to begood at it too. My poor old ears really went through it.We sailed from Scapa Flow into the Atlantic and for a few days it seemedquite peaceful. But, the weather had started to turn and the ship started aheavy roll. I’d never thought it could be so bad, at one time the ship was100 ft above the waves and in an instant we were 100 ft below. Evenexperienced sailors who had been aboard the ship for some time feltqueezy. Hammocks just swayed from side to side – if it had been on afairground it would have been fun. We never stopped thinking about U-

Boats. Just suppose a torpedo hit us, what would we do? How would we get off the ship? I was told that if you went intothe sea in the North Atlantic, you’d never get out of it alive as it was freezing cold. Many a good sailor perished in icy seas.Still, there was a job to do and after a time we all felt good about each other’s company. I made lots of friends, a couple ofthem were Masons like myself. We talked about our Lodges and the ritual. Sometime later we returned to Portsmouth andluckily we were given a few days leave. On return we sailed into the North Sea and joined a convoy of ships near theOrkneys heading for the Russian ports of Arkhangelsk (Archangel) or Murmansk. The Russians, so we were told, badlyneeded arms and equipment to continue the fight with the Germans. Churchill and Roosevelt had agreed to send inBritish and American ships to escort the merchantmen in a Lend-Lease Agreement.On the first run, it wasn’t too bad although we did encounter some German aircraft and one merchantship was sunk and afrigate was severly damaged. On the next run, it was completely different. The Germans had got wind of us approachingthe west coast of Norway and sent in bombers, submarines and anything else they could throw at us – we lost quite a fewships. It was now extremely cold – freezing, and the deck was covered in ice over 2 ft thick. Too much ice on a ship canaffect its bouyancy, so me and my mates regularly bashed and chipped away at the ice – it took me 4 hours to thaw outafterwards. I’d never shook so much in all my life with the cold. I never complain too much now if the weather in Britaingets cold, as it’s much bearable than winter in the Arctic Sea. Eventually, we arrived at the Russian port. Were they happyto see us? Well, I didn’t realise Vodka had so many flavours. The trip back in December 1943 was eventful. We’d heard thatthe German ship Scharnhorst was lurking around our neck of the woods. Action Stations was given to man the guns, andsure enough the German ship appeared on the horizon. Thankfully, other Royal Navy ships were present including thebattleship, HMS Duke of York and an action took place off the Norwegian North Cape in which the German ship was sunk.”Fact: Around 1,400 merchant ships left British ports under the Soviet Union’s Lend-Lease programme, escorted byships of the Royal Navy, the Royal Canadian Navy, and the US Navy. Eighty-five merchant vessels and sixteen RoyalNavy warships were lost. Over 3,000 sailors and mariners lost their lives.

Ice on HMS Belfast

The north Atlantic convoy routes

9 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

During WW2, the Police were responsible for sounding the sirens(before and after a raid), evacuating areas close to unexplodedbombs, controlling traffic away from incident sites as well as“maintaining law & order”. Shameless to say that occasionallylooting was an issue following bombing raids.The pre-war ranks were added to by a Police Reserve (usually retiredofficers), the Special Constabulary who were given a period of approvedtraining and a Police War Reserve. There was also a Women's AuxiliaryPolice Corps and the Police Auxiliary Messenger Service (the latterintended to keep lines of communication open).Many policemen whether in the regular service or in the ‘Specials’, carriedout many courageous acts endangering their own lives in the process.One such ‘Special’ was Sergeant W.Bro. Hugo de Lacy, a Freemason fromSt. Leonard’s Streatham Lodge.

On the night of 14th October, 1940 at 8.25pm, Bro. de Lacy whowas stationed at Streatham Police station, received a call fromScotland Yard to attend at Balham underground station,where a bomb had exploded on the tube station. The

station was nearly 3 miles away, but within a short timeofficers from the police station had arrived to see thecarnage of a direct hit on the station. The bomb hadexploded some 32 ft. down between a passage from the upand down lines, and a massive amount of debris had falleninto the tunnel. The rescue was obstructed by a No.88 buson the surface that had plunged into the crater caused bythe bomb. Every effort by firemen, police and the civildefence to locate and rescue people proved difficult anddangerous. Gas mains had been fractured along withsewage pipes and water had poured down into theunderground tunnels below.Bro. de Lacy and fellow officers attempted to push awaythe rubble to affect an escape route for survivors to climbthrough. The smell of gas started to overcome therescuers and several officers felt dizzy and unable tocontinue. The whole site could have seen even morecasualties had the gas been ignited by a spark.The station had been designated a civilian air raid shelter.Thousands of local residents had descended down into the tube toescape the Blitz. All along the Northern Line from the Elephant & Castleto Colliers Wood, people attempted to make a bed and were cheering

themselves by singing popular songswhen disaster struck. Sixty-six peopleincluding staff working in the tunnelsand platforms were killed as a result ofthe bomb mostly from drowning astons of water had filled the tunnels.Hugo de Lacy, exhausted after manyhours of digging in dangerousconditions retired to the make-shift teastall to refresh himself with a hot cupof tea. He then proceeded back to thesite to carry on digging for survivors foranother 5 hours before he was finallyrelieved. He had done his duty and hadfaced injury or death. Many months after, he received a letter of commendation from theChief Constable which he proudly hung framed in his home in Streatham. Memories ofthe disaster he would recall for many years after with sadness at the great loss of life.

Brave ‘Specials’ andMet. Policemen

10 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

The public found the tube safe except at 8.02pm on the14th October, 1940.

A deep crater caused by the Luftwaffe’s bomb at Balham

Heather Laughland (neé Robertson). Heather’s husband, Ian Laughland was aSurrey Freemason for over 60 years.

Heather, joined the Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens) shortlyafter the beginning of World War Two. She always enjoyed doingcrossword puzzles especially the ones with cryptic clues and wasrecruited to work at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, the secrethome of the World War Two codebreakers. After extensivesecurity checks and aptitude tests she was assigned to work asa Bombe Operator, part of a team which changed the cylinders(known as Bombes) on the machine designed by Alan Turingknown as Colossus. This was most probably the very firstelectronic and mechanical computer and was used to workout the sequence of numbers to break the German Enigmacode.

Heather never reallyspoke about her postingto her family untilaround 1990, and eventhen not much information was forthcoming,but on a nostalgic visit to Bletchley Parkmany years later, she happened to overheara man say that the hut that he had beenworking in was his office. Heather remarkedthat she had been working in the hut nextdoor, but neither of them knew each otheras they were not allowed to talk abouttheir work.

Nearly 10,000 people worked at the park and its surrounding area.Around 75 per cent were women, and of those six out of ten were uniformedpersonnel from the Women’s Services.

Mrs Heather LaughlandWomen’s Royal Naval Service

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

The Women’s Royal NavalService (WRNS; popularlyand officially known as theWrens) was the women’sbranch of the British RoyalNavy. First formed in1917 for the First WorldWar, it was disbanded in1919, then revived in1939 at the beginning ofthe Second World War,remaining active untilintegrated into the RoyalNavy in 1993. WRNsincluded cooks, clerks,wireless telegraphists,radar plotters, weaponsanalysts, range assessors,electricians and airmechanics.

German Enigma machine

A WW2 Wren

Wren Bombe OperatorsHeather’s certificate

Left: The Colossus computerBelow: Wrens on parade at Bletchley Park

Alan Turing

11 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

When war broke out, men joined up or were conscripted into the armedservices. Some already in the Police force and the National Fire Service choseto stay, but others readily became soldiers, sailors or airmen and many losttheir lives or sustained injuries during the war years. There were many menfrom local Freemasons’ Lodges who joined the forces or became ‘Specials’.

Those in the Surrey Constabulary were responsible fora whole range of tasks. It was the police who were normallythe first of the uniform services at the scene of bombings,crashed aircraft with all those dangers, capturing downedairmen, rescuing trapped people in buildings. Added tothis is the work and violence brought about by the largenumbers of soldiers in the county, many Canadians, manybored and frustrated and wanting to go home.

Never let anyone undermine the quality of the men ofthe Surrey Constabulary and other forces during thosedangerous times. They were committed, brave menundertaking their often-lonely duty and were key to thesafety of the Home Front. Here are just a very few of theincidents that they had to attend in 1940. There are manymore reports through to 1945, but as space is limited,here are just a few:1940, June 30th. First bomb fell on Surrey. From 30th June–31stDecember 1940, 5,668 high explosive bombs were dropped on theSurrey Constabulary area. 15th August. Over Redhill following araid, two Hurricane pilots from two Squadrons chased aMesserschmitt bringing it down when it exploded on Redhillairfield killing one of the crew the other being taken prisoner.Police Report from PC52, E. Beeney “I was on enquiries at Nutfieldwhen an air battle took place in a north-westerly direction. About7pm I observed an aircraft apparently out of control come down inspirals from a height of approximately five thousand feet in thedirection of Redhill Aerodrome. In the same section of sky aparachute was descending.” A PC went to the scene where he foundthe body of a German in the burnt out wreckage. The other crewmember that baled out landed at Merstham where he was capturedby Canadian soldiers the first prisoner of the war taken by theCanadians. PC Robert McBrien Surrey Constabulary awarded a BEMwhen at great personal risk he rescued a woman trapped under theruins of a house demolished by an enemy bomb at Horsley. SpecialConstable William Flower Symonds Reigate Borough Police:Symonds was approaching 50 years of age and was told that he wasfar too old to re-enlist in the Army on active service, instead hejoined the Reigate Police as a Special Constable, and served in that

capacity throughout the war. PC Burbidge served inthe Guildford Borough Police throughout the war as auniform beat officer and station officer in NorthStreet. He recalls that there were a great number ofCanadian troops billeted nearby and they caused agreat deal of trouble in Guildford as this was theirnearest town for recreation. Fights were common andpolice often ended up with their backs to the wall withtruncheons drawn. October 27th. A 1,000 lb bomb fellon 16 Emlyn Road, Earlswood, Reigate demolishing 5 houses and damaging 110. Sixpeople were killed and 24 had to be rescued. October 29th. Dorking: A bomb hitthe corner of Fraser Garden’s housing estate destroying two houses killing twosisters aged 12 and 20 when their home collapsed. Their parents and two brotherssurvive. A next- door neighbour is also killed. Box Hill had several large baskets ofincendiaries giving what many considered to be a firework display!Information obtained from: The History of the Surrey Constabulary. With thanks to: Robert Bartlett.

“The calm and authoritative way ofthe good-natured Bobby did more todispel panic than any amount of official propaganda”

WORLD WAR TWO

SURREY FREEMASONS

In January 1851, the Surrey Constabularybegan policing the county with a total of 70officers, the youngest of whom was 14 yearsold. Originally Guildford, Reigate andGodalming had separate borough policeforces. The Reigate and Guildford forces weremerged into Surrey’s in 1943.

The Special Constabulary is a force of trainedvolunteers who work with and support theirlocal police. ‘Specials’, as special constables areknown, come from all walks of life – they wereteachers, taxi drivers, accountants andsecretaries, or any number of other careers –and they all volunteered to do a minimum offour hours a week to their local police force,forming a vital link between the regular(full-time) police and the local community.

12 SURREY FREEMASONS Supporting and donating to the COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION

Dealing with an unexploded parachute bomb