What Holds the Modern Company Together? The short answer is culture. But which type is right for your organization? T ±b< by Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones organizational world is awash with talk of corporate culture-and for good reason. Culture has become a powerful way to hold a company together against a tidal wave of pressures for disintegration, such as decentralization, de-layering, and downsi: ing. At the same time, traditional mechanisms for integration-hierar- chies and control systems, among other devices-are proving costly and ineffective. Culture, then, is what remains to bolster a company's identity as one organization. Witbout culture, a company lacks values, direction, and purpose. Does tbat matter? For the answer, just observe any company with a strong eulture-and then compare it to one without. But what is corporate culture? Perhaps more important, is there one right culture for every organization? And if the answer is no-which we Rob Goffee is a professor of organizational behavioral London Business School Gareth fanes, formerly senior vice president for human resources at Polygram International in London, is a professor of oiganizational development at Henley Management College in Oxfordshire, England. Goffee and fanes are the founding partners of Creative Management Associates, an organizational consulting firm in London. —— —

71029510 Goffee Jones 1996 What Holds the Modern Company Together

Nov 08, 2014

71029510 Goffee Jones 1996 What Holds the Modern Company Together

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

What Holdsthe Modern

Company Together?

The short answer is culture.But which type

is right for your organization?

T±b<

by Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones

organizational world is awash with talk of corporate culture-and for good reason.Culture has become a powerful way to hold a company together against a tidal wave ofpressures for disintegration, such as decentralization, de-layering, and downsi:ing. At the same time, traditional mechanisms for integration-hierar-chies and control systems, among other devices-are proving costlyand ineffective.

Culture, then, is what remains to bolster a company's identity as oneorganization. Witbout culture, a company lacks values, direction, andpurpose. Does tbat matter? For the answer, just observe any company witha strong eulture-and then compare it to one without.

But what is corporate culture? Perhaps more important, is there oneright culture for every organization? And if the answer is no-which we

Rob Goffee is a professor of organizational behavioral London Business SchoolGareth fanes, formerly senior vice president for human resources at PolygramInternational in London, is a professor of oiganizational development atHenley Management College in Oxfordshire, England. Goffee and fanes arethe founding partners of Creative Management Associates, an organizationalconsulting firm in London.

—— —

CORPORATE CULTURE

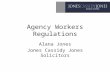

Two Dimensions, Four Cultures

high

Soc

iabi

lity

low

ilNetworked Communal

Fragmented Mercenary

low high

Solidarity

firmly believe-bow can a manager change an orga-nization's culture? Those three questions are thesubject of this article.

Culture, in a word, is community. It is an out-come of how people relate to one another. Commu-nities exist at work just as they do outside the com-mercial arena. Like families, villages, schools, andclubs, businesses rest on patterns of social interac-tion that sustain them over time or are their undo-ing. They are built on shared interests and mutualobligations and thrive on cooperation and friend-ships. It is because of the commonality of all com-munities that we believe a business's culture can bebetter understood when viewed through the samelens that has illuminated the study of human orga-nizations for nearly 150 years.

That is the lens of sociology, which divides com-munity into two types of distinct human relations:sociability and solidarity. Briefly, sociability is ameasure of sincere friendliness among members ofa community. Solidarity is a measure of a commu-nity's ability to pursue shared objectives quicklyand effectively, regardless of personal ties. Thesetwo categories may at first seem not to capture thewhole range of human behaviors, but they havestood the test of close scrutiny, in both academiaand the field.

What do sociability and solidarity have to dowith culture? The answer comes when you plot thedimensions against each other. The result is fourtypes of community: networked, mercenary, frag-mented, and communal. (See the matrix "Two Di-mensions, Four Cultures.") None of these culturesis "the best." In fact, each is appropriate for differ-ent business environments. In other words, man-

agers need not begin the hue and cry for one cul-tural type over another. Instead, they must knowhow to assess their own culture and whether it fitsthe competitive situation. Only then can they con-sider the delicate techniques for transforming it.

Sociability and Solidarityin Close Focus

Sociability, like the laughter that is its hallmark,often comes naturally. It is the measure of emotion-al, noninstrumental relations (those in whieh peo-ple do not see others as a means of satisfying theirown ends) among individuals who regard one an-other as friends. Friends tend to share certain ideas,attitudes, interests, and values and usually associ-ate on equal terms. In its pure form, sociability rep-resents a type of social interaction that is valued forits own sake. It is frequently sustained through con-tinuing face-to-face relations characterized by bighlevels of unarticulated reciprocity. Under these cir-cumstances, there are no prearranged "deals." Wehelp one another, we talk, we share, we laugh andcry together-with no strings attached.

In business communities, the benefits of high so-ciability are clear and numerous. First, most em-ployees agree that working in such an environmentis enjoyable, which helps morale and esprit decorps. Sociability also is often a boon to creativitybecause it fosters teamwork, sharing of informa-tion, and a spirit of openness to new ideas, andallows the freedom to express and accept out-of-the-box thinking. Sociability aiso creates an envi-ronment in which individuals are more likely to gobeyond the formal requirements of their jobs. Theywork harder than is technically necessary to helptheir colleagues-that is, their community-lookgood and succeed.

But there also are drawbacks to high levels of so-ciability. The prevalence of friendships may allowpoor performance to be tolerated. No one wants torebuke or fire a friend. It's more comfortable to ac-cept-and excuse-subpar performance in light ofan employee's personal problems. In addition, high-sociability environments are often characterized byan exaggerated concern for consensus. That is tosay, friends are often reluctant to disagree with orcriticize one another. In business settings, such atendency can easily lead to diminished debate overgoals, strategies, or simply how work gets done.The result: the best compromise gets applied toproblems, not the best solution.

In addition, high-sociability communities oftendevelop cliques and informal, behind-the-scenesnetworks that can circumvent or, worse, under-

134 PHOTO: JOANNE DUGAN/GRAPHISTOCK

What Is Your Organization's Culture?

To assess yuur urf>ani zation's level oi sociability,answer the following questions:

1.1'cuplc hcic try to make friends and to keep theirrelationships strong

2, People here get along very well

.V People in our group often socialize outside the office

4, People here really like one another

5. When people leave our group, we stay in touch

6, People here do favors for others hecause they like one another

7. People here often confide in une another aboutpersonal matters

To assess your organization's level of solidarity,answer the following questions:

1. Our group (organization, division, unit, team) understandsand shares the same business ohjectives

2. Work gets done effectively and productively

A. Our group takes strong action to address poor performance

4. Our collective will to win is high

5. When opportunities for competitive advantage arise,we move quickly to capitalize on them

6. We share the same strategic goals

7. We know who the competition is

luw medium high

mine due process in an organization. This is not tosay that high-sociability eompanies lack formal or-ganizational structures. Many of them are very hi-erarchical. But friendships and unofficial networksof friendships allow people to pull an end runaround the hierarchy. For example, if a manager insales hates the marketing department's new strate-gic plan, instead of explaining his or her oppositionat a staff meeting, the manager might talk it overdirectly (over drinks, after work) to an old friend,the company's senior vice president. Suddenly theplan might be canceled witbout the marketing de-partment's ever knowing why. In a best-case sce-nario, this kind of circumvention of systems lends aeompany a certain flexibility: maybe the marketingplan was lousy, and canceling it through official

routes might bave taken months. But in the worstcase, it can be destructive to loyalty, commitment,and morale. In other words, networks can functionwell if you are an insider-you know the right peo-ple, hear the right gossip. Those on the outside of-ten feel lost in the organization, mistreated by it, orsimply unable to affect processes or products in anyreal way.

Solidarity, by contrast, is based not so much inthe heart as in the mind, although it, too, can comenaturally to groups in business settings. Its rela-tionships are based on common tasks, mutual in-terests, or shared goals that will benefit all involvedparties. Labor unions are a classic example of high-solidarity communities. Likewise, the solidarity ofprofessionals - doctors and lawyers, for example-

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-Dccembei 1996 135

CORPORATE CULTURE

may be swiftly and ruthlessly mobilized if there isan outside competitive threat, such as proposedgovernment regulations that eould limit profitabil-ity. But, just as often, solidarity occurs between un-like individuals and groups and is not sustained bycontinuous social relations.

Consider the case of a Canadian clothing makerthat wanted to identify strategies to expand inter-nationally. Although its leaders were aware thatthe company's design, manufaeturing, and market-ing divisions had a long history of strained rela-

One of the great errors of therecent literature on corporateculture has been to assume thatorganizations are homogeneous.

tions, they assigned two managers from each toa strategy SWAT team. Despite very little socializ-ing and virtually no extraneous banter, the teamworked fast and well together - and for good reason:each manager's bonus was based on the team's per-formance. After the group's report was done-itsanalysis and recommendations were top-notch-the managers returned to their jobs, never to associ-ate again. In other words, solidarity can be demon-strated discontinuously, as the need arises. In con-trast to sociability, then, it can be expressed bothintermittently and contingently. It does not requiredaily display, nor does it necessarily rest upon a net-work of close friendships.

The organizational benefits of solidarity in abusiness community are many. Solidarity gener-ates a high degree of strategic focus, swift responseto competitive threats, and intolerance of poor per-formance. It also can result in a degree of ruthless-ness. If the organization's strategy is correct, thiskind of focused intent and action can be devastat-ingly effective. The ruthlessness, by the way, ean it-self reinforce solidarity: if everyone has to performto strict standards, an equality-of-suffering effectmay occur, building a sense of community inshared experience. Finally, when all employees areheld to the same high standards, they often developa strong sense of trust in the organization. Thiscompany treats everyone fairly and equally, thethinking goes; it is a meritocracy that cuts no spe-cial deals for favored or connected employees. Intime, this trust can translate into commitment andloyalty to the organization's goals and purpose.

But, Uke sociability, solidarity has its costs aswell. As we said above, strategic focus is good aslong as it zeroes in on the right strategy. But if thestrategy is not the right one, it is the equivalent ofcorporate suicide. Organizations can charge rightover the cliff with great efficiency if they do thewrong things well. In addition, cooperation occursin high-solidarity organizations only when the ad-vantage to the individual is clear. Before takingon assignments or deciding how hard to work onprojects, people ask, "What's in it for me?" If the

answer is not obvious or immediate,neither is the response. '

Finally, in high-solidarity organi-zations, roles (that is, job definitions)tend to be extremely clear. By con-trast, in cultures where people arevery friendly, roles and responsibili-ties tend to blur a bit. Someone insales migbt become deeply involvedin a new R&D project-a collabora-tion made possible by social ties.

This kind of overlap usually doesn't happen in bigh-solidarity environments. Indeed, sucb environ-ments are often characterized by turf battles, as in-dividuals police and protect the boundaries of theirroles. Someone in sales who tried to beeome in-volved in an R&D effort would be sent packing-and quickly.

Although our discussion separates sociabilityand solidarity, many observers of organizational lifeconfuse the two, and it is easy to see why. The con-cepts can, and often do, overlap. Social interactionat work may reflect the sociability of friends, thesolidarity of colleagues, both, or-sometimes-nei-ther. Equally, when colleagues socialize outsidework, their interaetion may represent an extensionof workplace solidarity or an expression of intimateor close friendship. Yet to identify a community'sculture correctly and to assess its appropriatenessfor the business environment, it is more than aca-demic to assess sociability and solidarity as distinctmeasures. Asking the right questions can help inthis process. (See the questionnaire "What Is YourOrganization's Culture?")

It is critical, before completing the form, to selectthe parameters of the group you will be evaluating;for instance, you might assess your entire companywith all its divisions and subgroups or a unit assmall as a team. Either is fine, as long as you do notchange horses in midstream. Our unit of analysishere is primarily the corporation, but we recognizetbat executives may use the framework to look in-side their own organizations, comparing units, divi-sions, or other groups with one another.

136 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW Novcmbcr-Dctcmbcr 1996

Such an exercise can indeed be instructive. Oneof the great errors of the recent literature on corpo-rate culture has heen to assume that organizationsare homogeneous. Just as one organization differsfrom another, so do units within them. For exam-ple, the R&D division of a pharmaceutical compa-ny might differ markedly from the manufacturingdivision in hoth solidarity and sociahility. In addi-tion, there are often hierarchical differences withina single company: senior managers may display anentirely different culture from middle managers,and different still from blue-collar workers.

Is this variation good news or bad news? The an-swer depends on the situation and requires manage-rial judgment. Radically different cultures inside aeompany may very well explain conflict and sug-gest that intervention is necessary. Similarly, onetype of culture throughout a corporation may be asignal that some forms need to be adjusted to ac-count for differing husiness environments.

The Networked Organization:High Sociability, Low Solidarity

It is perhaps the rituals of what we call net-worked organizations that are most noticeable tooutsiders. People frequently stop to talk in the hall-ways; they wander into one another's offices withno purpose hut to say hello; lunch is an event inwhicb groups often go out and dine together; and af-ter-hours socializing is not the exception but therule. Many of these organizations celehrate birth-days, field softball teams, and hold parties to honoran employee's long service or retirement. Theremay he nicknames, in-house jokes,or a common language drawn fromshared experiences. (At one net-worked company, for instance, em-ployees tease one another with thephrase "Don't pull a Richard," in ref-erence to an employee who once fellasleep during a meeting. Richardhimself uses the jest as well.) Em-ployees in networked organizationssometimes act like family, attendingone another's weddings, anniversary parties, andchildren's confirmations and har mitzvahs. Theymay even live in the same towns.

Inside the office, networked cultures are charac-terized not hy a lack of hierarchy hut hy a profusionof ways to get around it. Friends or cliques of friendsmake sure that decisions about issues are made he-fore meetings are held to discuss them. Peoplemove from one position to another without the"required" training. Employees are hired without

going through official channels in the human re-sources department-they know someone insidethe network. As we have said, this informality canlend flexibility to an organization and be a healthyway of cutting through the bureaucracy. But it alsomeans that the people in tbese cultures bave de-veloped two of tbe networked organization's keycompetencies: the ability to collect and selectivelydisseminate soft information, and the ahility toacquire sponsors or allies in the company who willspeak on their bebalf both formally and informally.

What are the other hallmarks of networked orga-nizations? Their low levels of solidarity mean thatmanagers often have trouble getting functions oroperating companies to cooperate. At one large Eu-ropean manufacturer, personal relations among se-nior executives of businesses in France, Italy, theUnited Kingdom, and Germany were extremelyfriendly. Several executives had known one anotherfor years; some even took vacations together. Butwhen the time came for corporate headquarters toparcel out resources, those same executives foughtacrimoniously. At one point, they individually sub-verted attempts by headquarters to introduce aEurope-wide marketing strategy designed to com-bat the entry of U.S. competition.

Finally, a networked organization is usually sopolitical that individuals and cliques spend muchof their time pursuing personal agendas. It becomesbard for colleagues to agree on priorities and formanagers to enforce them. It is not uncommon tobear frequent calls for strong leadersbip to over-come the divisions of suhcultures, cliques, or war-ring factions in networked organizations.

Networked organizations arecharacterized not by a lack of

hierarchy but by a profusion ofways to get around it.

In addition, because there is little commitmentto shared business objectives, employees in net-worked organizations often contest performancemeasures, procedures, rules, and systems. For in-stance, at one international consumer-productscompany witb wbich we have worked, the strategicplanning process, the structural relationship be-tween corporate headquarters and operating com-panies, and the accounting and budgetary controlsystems were beavily and continually criticized hy

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1996 137

Unilever: A Networked OrganizationThere is a frequently told story within Unilever, the

Anglo-Dutch consumer-goods group with worldwidesales of roughly $50 billion. Unilever executives, it issaid, recognize one another at airports, even whenthey've never met before. There's something about theway they look and act - something so subtle it's im-possible to pin down in words yet unmistakable tothose who have worked for the company for more thana few years.

Obviously, there's a bit of exaggeration in this com-pany legend, hut it underscores Unilever's tradition asa networked company - that is, one with a culturecharacterized by high levels of sociability. For years,the company has explicitly recruited compatible peo-ple - people with similar backgrounds, values, and in-terests. Unilever's managers believe that this corps oflike-minded individuals is tbe reason why its employ-ees work so well togetber despite tbeir national diver-sity, why tbey demonstrate such strong loyalty totheir colleagues, and why tbey embrace the company'svalues of cooperation and consensus.

Unilever takes otber steps to reinforce and increasetbe sociability in its ranks. At Four Acres, tbe compa-ny's international-management-training center out-side London, bundreds of executives a year partake inactivities rich in social rituals: multicourse dinners,group photographs, sports on the lawn, and, perhapsabove all, a bar that literally never closes. As formerchairman Floris Maljers remarks, "Tbis shared experi-ence creates an informal network of equals wbo knowone another well and usually continue to meet andexchange experiences."

In addition to the events at Four Acres, Unilever'ssociability is bolstered by annual conferences attend-ed by tbe company's top 500 managers. Tbe compa-ny's leaders use tbese meetings to communicate andreview strategy, but tbere is much more to them thanwork. (Tbe intense fraternizing that takes place atthese conferences has eamed them the nickname Oh!Be Joyfuls!) Maljers notes, "Over good food and drink,our most senior people meet, exchange views, and re-confirm old friendships."

Finally, Unilever moves its young managers fre-quently - across horders, products, and divisions. Tbiseffort is an attempt to start Unilever relationsbips ear-ly, as well as to increase know-how.

Yet these carefully nurtured patterns of sociahilityhave not always been matched hy bigh levels of com-panywide solidarity. Unilever bas found it hard overthe years to achieve cross-company coordination andagreement on objectives. It's not tbat executives fightover strategy as much as "talk it to death" in thesearch for consensus, says one senior vice president.

Does this networked culture fit Unilever's businessenvironment? In good part, yes. Unilever's managershail from dozens of countries. This diversity couldhave been an isolating factor, hindering the flow of in-formation and ideas. But because of the culture's bighlevels of sociability, there is widespread fellowshipand goodwill instead. Second, a key success factor inUnilever's business is proximity to local markets. Tbeorganization's low solidarity has kept units focused ontheir home bases with good results, And finally, untilrecently, Unilever has been a highly decentralized or-ganization. Simply put, tbere has been little need forstrategic agreement among units.

But Unilever's environment might very well hechanging witb tbe emergence of a single Europeanmarket, which would make coordination among busi-nesses and functions imperative. Indeed, many recentorganizational cbanges - tbe creation of Lever Europein the detergents business, for example - can he inter-preted as an attempt hy Unilever to create higher lev-els of cor^jorate solidarity, largely through a process ofcentralization.

In addition, Unilever faces some competitors, sucbas Procter & Gamble and L'Oreal, known for tbeir higblevels of solidarity around corporate goals. Tbis assetbas lent Unilever's competitors the ability to acceler-ate product development processes and exploit marketopportunities quickly. Unilever must match thosecompetencies or risk losing clout.

Finally, Unilever's relative lack of solidarity meansthat management can lose its sense of urgency - a

executives in country husinesses. Indeed, the criti-cism even took on an element of sport, increasingsociability among employees hut doing nothing forthe already diminished levels of solidarity.

Generally speaking, few organizations start theirlife cycle in the networked quadrant. By definition,sociability is huilt up over time. It follows, then,that many organizations migrate there from otherquadrants. And despite the political nature of thiskind of community, there are many examples of

successful networked corporations. These organi-zations have learned how to overcome the nega-tives of sociahility, such as cliques, gossip, and lowproductivity, and how to reap its henefits, such asincreased creativity and commitment. One methodof maximizing the henefits of a networked cultureis to move individuals regularly hetween functions,businesses, and countries in order to limit exces-sive local identification and help them develop awider strategic view of the organization. Later on.

138 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1996

competitive advantage in any business environment.Tbis challenge is well known to tbe company's lead-ers. As Maljers bimself notes, "Everybody may be sobusy with friends elsewhere - witb the interestingtraining program, the well-organized course, the nextmajor conference - tbat complacency sets in. Unfortu-nately, we have seen this happen in some of our units,especially tbe more successful ones. It may be neces-sary to shake up the system from time to time."

This comment underlines one of tbe higgest risks ofthe networked organization. Employees may be sobusy being friends that they lose sight of the reasontbey are at work in tbe first place.

Interestingly, Unilever's recently announced orga-nizational restructuring is designed in part to addresssome of the negative consequences of the networkedform. The company will be broken into 14 businessgroups, and, according to tbe plan, eacb will have aclear husiness rationale, stretcb targets, and transpar-ent accountability. In a booklet sent to all managers,the company described the changes as a means to "es-tablish a simple, effective organization dedicated tothe needs of the future. Tbis must provide great clarityof roies, responsibilities, and decision making.... Un-der the new structure, business groups will make an-nual contracts on which they must deliver come 'hellor high water.'"

Similarly, in an interview in the September issue ofUnilever magazine, company chairman Niall FitzGer-ald identified the values of the new organization inthese words: "Simplicity, clarity, and delegation of au-thority are intended to be tbe prime virtues of the neworganization. A disciplined approach |is essential] -those who have been given tbe task of delivering re-sults must focus on delivering."

In tbe terms of our model, this reorganization isclearly an effort to move toward the mercenary quad-rant: less politicking (as enjoyable as it migbt he) anda more rutbless focus on results. But can Unilever letgo of its ingrained sociahility and take on the behaviorsof a bigh-solidarity enterprise? The company's futureperformance will tell.

these individuals often hecome the primary man-agers of the networked organization's politicalprocesses, and they keep them healthy.

High levels of sociability usually go hand in handwith low solidarity hecause close friendships caninhibit the open expression of differences, the criti-cism of ideas, and forceful dissent. Constructiveconflict, however, is often a precondition for devel-oping and maintaining a shared sense of purpose-that is, solidarity. It would not be surprising, then.

to find that well-meaning management interven-tions to increase strategic focus often consolidateworkplace friendships hut do little for organization-al solidarity. That could account for at least some ofthe frustrations of those who complain, for exam-ple, that the outdoor team-huilding weekend wasgreat fun but not remotely connected to the dailywork of ensuring that the different parts of the husi-ness are integrated.

As we have noted, each type of corporate culturehas its most appropriate time and place. We haveobserved that the networked organization func-tions well under the following business conditions:DWhen corporate strategies have a long timeframe. Sociahility maintains allegiance to the orga-nization when short-term calculations of interestdo not. Consider the case of a company expandinginto Vietnam. It might he years hefore such an ef-fort is profitable, and in the meantime the processof getting operations running may he difficult andfrustrating. In a networked culture, employees areoften willing to put up with risk and discomfort.They are loyal to their colieagues in an open-endedway. The enjoyment of friendship on a daily basis isits own reward.DWhen knowledge of the peculiarities of localmarkets is a critical success factor. The reason isthat networked organizations are low on solidarity:memhers of one unit don't willingly share ideas orinformation with members of another. This wouldcertainly he a strategic disadvantage if successcame from employees having a broad, big-pictureperspective. But when success is driven hy deep andintense familiarity with a unit's home turf, low sol-idarity is no hindrance.n When corporate success is an aggregate of localsuccess. Again, this is a function of low solidarity. Ifheadquarters can do well with low levels of inter-divisional communication, then the networkedculture is appropriate.

The Mercenary Organization:Low Sociability, High Solidarity

At the other end of the spectrum from the net-worked organization, the tnercenary community islow on hallway hobnobhing and high on data-ladenmemos. Indeed, almost all communication in amercenary organization is focused on husiness mat-ters. The reason: individual interests coincide withcorporate objectives, and those ohjectives are oftenlinked to a crystal clear perception of the "enemy"and the steps required to heat it. As a result, merce-nary organizations are characterized hy the ahilityto respond quickly and cohesively to a perceived

HARVARD BUS[NESS REVIEW November-December 1996 139

Mastiff Wear: A Mercenary OrganizationSeveral years ago, a senior manager at a company

we'll call Mastiff Wear, an international manufacturerof popular children's clothing, invited 15 of tbe com-pany's top executives to dinner at a fancy new restau-rant in London. The men and women had just satdown when the host announced a challenge to be com-pleted over dinner: devise a new advertising slogan.The best solution, tbe host said, would earn a bottle ofDom Perignon. For tbe next three hours, the gueststook to their task singlc-mindedly, even tearing up theelegant menus to use as working paper. The restau-rant's delicacies passed before them throughout thenight, and the executives ate, but few seemed to takenotice of where tbey were. What they were doing wasall that mattered.

Not long after, one of the authors of this article metwitb a similar group of executives at Mastiff Wear. "IfI join Mastiff next Monday," he asked them, "whatshould I know are the rules of success at tbis organiza-tion?" Rule one, he was told: Arrive on Sunday. Ruletwo: Call your family and tell them you won't behome until next weekend.

Botb of these stories illustrate a typical mercenaryculture in action: members work long hours and oftenvalue work over family life. (The executives in therestaurant worked even wben tbey could have beensocializing, and no one complained - or even noticed.)In addition, the stories illustrate this form's bigh de-gree of internal competition and strong focus on theachievement of tasks.

Mastiff also embodies several other characteristicsof high-solidarity cultures. There are strict standardsfor performance, and underachievers are dealt withruthlessly, As one executive remarks, "Once in awbile, one of us just disappears." Those who surviveare well rewarded - so well tbat many are able to retire

early. Indeed, a common strategy for a Mastiff execu-tive is to work hard, even at tbe cost of bis or her per-sonal life, accumulate wealth, and then leave. Rela-tionsbips with the organization exist primarily as ameans for employees to promote their own interests -career, personal, or otherwise.

In some ways, tbis mercenary culture bas been anapt fit for Mastiff in recent years. The company hashad considerable success in the clearly defined distri-bution channels in which it operates. Internally, afierce focus on efficiency has ensured that resourcesare used to the fullest. Little is wasted, and tbe com-pany does only what it can do best, creating centers ofcorporate excellence to spread its knowledge. Exter-nally, a strategy of targeting clearly defined sectors -primarily department stores and catalogs - and aclearly identified "enemy" has consistently en-abled Mastiff to establish dominant market positions.Most recently, this ability has been illustrated by tbecompany's dramatic entry into the European mar-ket - a move that has inflicted considerable damageon a major competitive player there.

But mercenary cultures bave tbeir sbortcomings.When you successfully occupy tbe number one posi-tion in many markets, as Mastiff has for many years,you may run out of enemies. As a result, you may losethe competitive edge that originally brought yourcompany a sense of urgency and the collective will towin. In addition. Mastiff, like many mercenary cul-tures, may have suffered from excessive strategicfocus. In this case, a characteristic concern with oper-ational efficiencies proved harely adequate when com-petitors were gaining market share from new-productdevelopment. Focusing on one or two issues is astrength, of course. The danger is that you can losesight of wbat's bappening on the horizon.

opportunity or threat in the marketplace. Prioritiesare decided swiftly-generally by senior manage-ment-and enforced throughout the organizationwith little dehate.

Mercenary organizations are also characterizedhy a clear separation of work and social life. (Inter-estingly, these cultures often consist of peoplewhose work takes priority over their private life.)Members of this kind of business communityrarely fraternize outside the office, and if they do, itis at functions organized around business, such as aparty to celebrate the defeat of a competitor or thesuccessful implementation of a strategic plan.

Because of the ahsenee of strong personal ties,mercenary organizations are generally intolerant of

poor performance. Those who are not contributingfully are fired or given explicit instructions on howto improve, with a firm deadline. There is a hard-heartedness to this aspect of mercenary cultures,and yet the high levels of commitment to a com-mon purpose mean it is accepted, and usually sup-ported, in the ranks. If someone has not performed,you rarely hear, for instance, "It was a shame wehadtolet John go-he was so nice." John, the think-ing would he, wasn't doing his part toward clearlystated, shared strategic ohjectives.

Finally, the low level of social ties means thatmercenary organizations are rarely bastions of loy-alty. Employees may very well respect and liketheir organizations,- after all, these institutions are

140 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1996

CORPORATE CULTURE

usually fair to those who work hard and meet stan-dards. But those feelings are not sentimental or tiedto affectionate relationships hetween individuals.People stay with high-solidarity companies for aslong as their personal needs are met, and tben theymove on.

Without a doubt, tbe advantages of a mercenaryorganization ean sound seductive in tbe perfor-manec-driven 1990s. What manager would notwant his or her company to have a heightened senseof competition and a strong will to win; In addi-tion, because of their focused activity, many merce-nary organizations are very productive. Moreover,unhindered hy friendships, employees are not re-luctant to compete, further enhancing performanceas standards get pushed ever higher.

But mercenary communities have disadvantagesas well. Employees wbo are busy chasing specifictargets are often disinclined to cooperate, share in-formation, or exchange new or creative ideas. To doso would be a distraction. Cooperation betweenunits with different goals is even less likely. Con-sider the example of Warner Brothers, the enter-tainment conglomerate. Tbe music and film divi-sions, each with its own strategic targets, havetrouble achieving synergy-for example, witbsound tracks. (Musicians recording on a Warnerrecord label, for instance, might be ealled on toscore a Warner movie.) Compare this situation withthat at Disney, a major competitor, which relent-lessly and profitably exploits synergies between itsmovie characters-from Snow White to Simba -and its merchandising divisions.

Tbe mercenary organization works effectivelyunder the following business conditions:LJ When change is fast and rampant. Tbis type ofsituation calls for a rapid, focused re-sponse, whicb a mereenary organiza-tion is able to mount.DWben economies of scale areacbieved, or competitive advantageis gained, through creating corporatecenters of excellence that can im-pose processes and procedures on op-erating companies or divisions. Forexample, the Ziirieh-based diversi-fied corporation ABB Asea BrownBoveri builds worldwide centers of excellence forproduct groups. Its Finnish subsidiary Strombergbas become the world leader in electric drives sinceits acquisition in 1986, and it now sets the standardfor the ABB empire.( 1 When corporate goals are clear and measurable,and there is therefore little need for input from tberanks or for consensus building.

n Wben the nature of the competition is clear. Mer-cenary organizations thrive when the enemy-andthe best way to defeat it-are obvious. The merce-nary organization is most appropriate wben one en-emy can be distinguisbed from many. Komatsu, forexample, made Marv-C-translated as "EncircleCaterpillar"-its war cry back in 1965 and focusedall its strategic efforts during tbe 1970s and early1980s on doing just that, aided effectively hy ahigh-solidarity culture. By contrast, IBM zigzaggedstrategieally for years, unable to identify its compe-tition until tbe game was nearly up. Its culturaltype during that time is not known to us, but weean guess with confidence that it wasn't mercenary.

The Fragmented Organization:Low Sociability, Low Solidarity

Few managers would volunteer to work for or,perhaps harder still, run a fragmented organization.But like strife-ridden countries, unfriendly neigb-borboods, and disharmonious families, sucb com-munities are a fact of life. Wbat are their primarycharacteristics in a business setting?

Perhaps most notahly, employees of fragmentedorganizations display a low consciousness of orga-nizational membership. They often believe thatthey work for themselves or they identify witb oc-cupational groups-usually professional. Asked at aparty wbat he does for a living, for instance, a doc-tor at a major teaching bospital tbat happens tobave this kind of eulture might reply, "I'm a sur-geon," leaving out the name of the institutionwbere be is employed. Likewise, organizationsthat have tbis kind of culture rarely field softhallteams-who would want to wear tbe company's

In mercenary organizations,you rarely hear, for instance,''It was a shame we had to let

John go - he was so nice."

name on a T-shirt? -and employees engage in noneof tbe extracurricular rites and rituals that charac-terize high-sociability cultures, considering them awaste of time.

This lack of affective interrelatedness extends tobebavior on the job. People work witb tbeir doorsshut or, in many cases, at home, going to the officeonly to eolleet mail or make long-distance calls.

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1996 141

CORPORATE CULTURE

They are often secretive about their projects andprogress with coworkers, offering information onlywhen asked point-blank. In extreme cases, mem-bers of fragmented organizations have such low lev-els of sociability that they attempt to sabotage thework of their "colleagues" through gossip, rumor,or overt criticism delivered to higher-ups in the or-ganization.

This culture also has low levels of solidarity: itsmembers rarely agree about organizational objec-tives, critical success factors, and performancestandards. It's no surprise, then, that high levels ofdissent about strategic goals often make these orga-nizations difficult to manage top-down. Leaders of-ten feel isolated and routinely report feeling as ifthere is no action they can take to effect change.Their calls fall on deaf ears.

Low sociability also means that individuals maygive of themselves on a personal level only aftercareful calculation of what they might get in re-turn. Retirement parties, for example, are often

sparsely attended. Indeed, any social behavior thatis discretionary is unlikely to take place.

We realize it must sound as if fragmented organi-zations are wretched places to work - or at least ap-peal only to the hermits or Scrooges of the businessworld. But situations do exist that invite, or evenbenefit from, such a culture, and further, this kindof environment is attractive to individuals who pre-fer to work alone or to keep their work and personallives entirely separate.

In our research, we have seen fragmented organi-zations operate successfully in several forms. First,the culture functions well in manufacturing con-cerns that rely heavily on the outsourcing of piece-work. Second, the culture can succeed in profes-sional organizations, such as consulting and lawfirms, in which highly trained individuals haveidiosyncratic work styles. Third, fragmented cul-tures often accompany organizations that havebecome virtual: employees work either at home oron the road, reporting in to a central base mainly by

University Business School: A Fragmented OrganizationDespite how unpleasant it sounds to work where

both sociability and solidarity are lacking, there areindeed environments that invite such cultures and dono harm whatsoever to the organization, its people, orits products in the process. Still, there is the stigma ofan "unfriendly" organization to contend with, whichis the reason this case study uses a disguised name forits subject.

University Business School is typical of its breed: itoffers an M.B.A. program and several shorter execu-tive programs. Its other products are books, reports,and scholarly articles. The school achieves all thissmoothly, with remarkably low levels of social inter-action of any kind among members of the community.

Take sociability. At UBS, professors work mainlyon their own, researching their specialty, preparingclasses, writing articles, and assessing students' papers.Often this work is done at home or in the office, be-hind closed doors displaying Do Not Disturb signs.Many professors have demanding second jobs as con-sultants to industry. Therefore, when social contactdoes occur, it is with clients, students, or researchsponsors rather than with colleagues. In fact, facultymembers may actively avoid sociability on campusin order to maximize discretionary time for privateconsulting work and research for publication.

As for solidarity, UBS professors see themselvesforemost as part of an international group of scholars,feeling no particular affinity for the institution thatemploys them. Their occupational group, they be-

lieve, sets the standards and controls outputs, such asjournal articles. In addition, it shapes employment op-portunities and determines career progress. There isno point, the professors' thinking goes, concerningthemselves with the goals and strategies of an institu-tion that does not have direct bearing on their day-to-day work or future pursuits.

As we have said, however, none of this diminishedsociability or solidarity compromises the competitiveposition of UBS, a highly renowned institution. Thereason is that many professors do indeed do their bestwork alone or with scholars from other institutionswho share similar interests. Moreover, M.B.A. andother academic programs don't necessarily need inputfrom groups of staff memhers; most professors knowwhat to teach and are disinclined in any case to takethe advice of others. Indeed, the only reason for meet-ings in this environment is to decide on academic ap-pointments and promotions. This activity involvesconsideration of scholarship, which requires neithersociability nor solidarity. Finally, UBS need not worrythat its employees are losing focus or urgency abouttheir work - one of the biggest risks of low-solidarityorganizations. On the contrary. UBS attracts a self-selecting group of highly autonomous, sometimesegocentric individuals who are motivated, not alienat-ed, by the freedoms of the fragmented organization.

In short, the success of UBS underscores our point:there is no generic ideal when it comes to corporatecommunity. If the culture fits, wear it.

142 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December

eleetronic means. Of course, fragmented organiza-tions sometimes refleet dysfunctional eommuni-ties in whieh ties of sociability or solidarity havebeen torn asunder by organizational politics, down-sizing, or otber forms of disruption. In tbese cases,tbe old ties of friendship and loyaltyare replaced hy an overriding eon-cern for individual survival, unleash-ing a war of all against all.

The last unhealthy scenario aside,however, a fragmented culture is ap-propriate under tbe following busi-ness conditions:n When there is little interdepen-dence in tbe work itself. This migbt occur, for ex-ample, in a company in which pieces of furniture orclothing are subcontracted to individuals who workout of their homes and then assembled at anothersite. A second example might be a firm composed oftax lawyers, each working for different clients.D When significant innovation is produced primar-ily hy individuals rather than by teams. (This, itshould be noted, is beeoming increasingly rare inhusiness, as cross-disciplinary teams demonstratethe power of imJike minds working together.)n When standards are achieved hy input eontrols,not process controls. In these organizations, timehas proven that management's foeus should be onrecruiting the right people; once tbey have beenhired and trained, their work requires little supervi-sion. They are tbeir own hest judges, their ownbarshest taskmasters.G When tbere are few learning opportunities be-tween individuals or when professional pride pre-vents the transfer of knowledge. In an internationaloil-trading company we have worked with, for ex-ample, employees who traded Nigerian oil nevershared market information with employees tradingSaudi crude. For one thing, they weren't given anyincentive to take tbe time to do so; for another,each group of traders took pride in knowing morethan the other. To give away information was togive away the prestige of being at tbe top of tbefield-a market insider.

The Communal Organization:High Sociability, High Solidarity

A communal eulture can evolve at any stage of acompany's life cycle, but when we are asked to il-lustrate this form, we often cite the characteristicsof a typical small, fast-growing, entrepreneurialstart-up. The founders and early employees of sucbcompanies are close friends, working endless hoursin tight quarters. This kinship usually flows into

close ties outside tbe office. In tbe early days ofApple Computer, for instance, employees lived to-gether, commuted together, and spent weekendstogether, too. At the same time, tbe sense of solidar-ity at a typical start-up is sky bigh. A tiny company

People in fragmentedorganizations often work with

their doors shut or at home.

has one or at most two products and just as fewgoals (tbe first usually being survival). Becausefounders and early employees often have equity inthe start-up, success has clear, collective benefits.In communal organizations, everything feels in syne.

But, as we have said, start-ups don't own this cul-ture. Indeed, communal cultures can be found inmature companies in which employees haveworked together for decades to develop both friend-ships and mutually beneficial objectives.

Regardless of their stage of development, eom-munal organizations sbare certain traits. First, tbeiremployees possess a high, sometimes exaggerated,consciousness of organizational identity and mem-bership. Individuals may even link their sense ofself with the corporate identity. Some employees atNike, it is said, have tbe company's trademark sym-bol tattooed ahove their ankles. Similarly, in tbeearly days of Apple Computer, employees readilyidentified themselves as "Apple people."

Organizational life in communal companies ispunetuated by social events that take on a strongritual significance. The London office of the inter-national advertising agency J. Walter Thompson,for instance, throws parties for its staff at exciting,even glamorous, locations; recent events were heldat the Hurlingham Club and the Natural HistoryMuseum in London. The company also offers itsemployees a master class on creativity tbat featuresa speeeh by a celebrity. Dave Stewart, former gui-tarist of the rock band the Eurythmies, even playeda set during his presentation. And finally, Thomp-son bolds an annual gala awards ceremony for thecompany's best creative teams. Winners go to lunchin Paris. Other communal companies celebrate en-tranee into tbeir organizations and promotionswitb similar fanfare.

The high solidarity of communal cultures is of-ten demonstrated through an equitable sharing ofrisks and rewards among employees. Communalorganizations, after all, place an extremely bigb

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1996 143

British-Borneo Petroleum Syndicate: A Communol OrganiSynergy is a term that gets bandied about quite a bit,

as in "Wouldn't it be terrific if our divisions, operatingcompanies, or functional areas had more synergy?Then they could learn from one anotber and sbare newideas - even exchange market or technological infor-mation." Tbis bope, while admirable in theory, oftenremains just tbat in practice-a hope.

Not so at British-Borneo Petroleum Syndicate,where a communal culture - combining bigb sociabil-ity and high solidarity-dovetails effectively with thecompany's strategic need for cooperation and inter-change among functions and locations. Indeed, tbesynergy among groups at British-Borneo is perbaps itsgreatest competitive advantage. The London-basedcompany, which has grown more than tenfold in the1990s to reach a market capitalization of $550 millionin 1996, explores for and produces oil and gas in theNorth Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. Success in thiskind of endeavor arises from speed of movement, riskmanagement, and the innovative use of technology-which in this context can come only out of cross-func-tional teams. Success is also linked to well-orcbes-trated, complex interfaces with other players in themarket and with governments. And finally, successcomes from employees committing to strategies thatare rather long-term. The exploration phase for mostventures will take several years, and production-hence casb flow - often lags a few years beyond that.

British-Borneo's higb levels of sociability can beseen in the honest and relaxed way employees inter-

act. They talk about tbeir feelings openly and oftenbelp one anotber out - without making deals. In addi-tion, they are a team that plays together out of the of-fice-at picnics, parties, and ball games. This convivi-ality is, in some part, management's doing. Managershave systematically tried to recruit compatible peoplewith similar interests and backgrounds. And theyhave improved on tbis foundation witb regular team-building events such as Outward Bound courses for allnew bires, frequent social events, and active supportof company softball, track, and sailing teams. Every-one in tbe company is invited to participate, fromboard members to clerks.

British-Borneo's sociability, bowever, has not comeat tbe expense of solidarity. The company's employeesdisplay a strong sense of urgency and will to win. Theyare clearly committed to a common purpose. Indeed,in the United Kingdom, the company's strategy isknown and understood by people of every rank, in-cluding secretaries and other support personnel. Thewidespread knowledge and acceptance of British-Borneo's objectives have come about through carefuleffort. The company devotes considerable time andenergy to bammering out - tbrougb workshops andbrainstorming sessions - a collective vision that isowned by the staff.

Interestingly, despite tbe company's high levels ofsociability, British-Borneo employees are not reluc-tant to speak tbeir mind. (Ordinarily, friendships pre-clude tough criticism or disagreement.) Staff members

value on fairness and justice, which comes intosharp focus particularly in hard times. For example,during the 1970 recession, rather than lay peopleoff, Hewlett-Packard introduced a 10% cut in payand hours across every rank. It should be noted thatthe company's management did not become demo-nized or despised in the process. In fact, what hap-pened at Hewlett-Packard is another characteristicof communal companies: their leaders eommandwidespread respect, deference, and even affection.Although they invite dissent, and even succeed inreceiving it, their authority is rarely challenged.

Solidarity also shows itself clearly v hen it comesto company goals and values. The mission state-ment is often given front-and-center display in acommunal company's offices, and it evokes enthu-siasm rather than cynicism.

Finally, in communal organizations, employeesare very clear about the competition. They knowwhich companies threaten theirs-what they dowell, how they are weak-and bow they can he

overcome. And not only is the external competi-tion seen clearly, its defeat is also perceived to he amatter of competing values. The competition hasas much to do with an organization's purpose-thereason it exists-as it has with winning marketshare or increasing operating margins.

Given all these characteristics, it is perhaps notsurprising that many managers see the communalorganization as the ideal. Solidarity alone may besymptomatic of excessive instrumentaiism. Em-ployees may withdraw their cooperation the mo-ment they become unable to identify shared advan-tage. In some cases, particularly where there arewell-established performance-related reward sys-tems, this attitude may be reflected in an exagger-ated concern with those activities that producemeasurable outcomes. By contrast, organizationsthat are characterized primarily by sociability maylose tbeir sense of purpose.

However, where both sociability and solidarityare high, a company gets the best of both worlds - or

144 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1996

zationarc encouraged to strip things down to reality whenthey communicate about the cotiipany's business.This frankness creates an atmosphere of challenge andJcbnte, which is one of the hallmarks of a high-solidar-ity L-nvironmcnt.

Finally, British-Borneo is a classic high-solidarityenvironment in its adherence to strict performancestandards. The culture docs nut tolerate underachicve-nient. Outstanding results arc generously rewarded,hut it is not unusual for someone who docs not mea-sure up to he asked to leave, sooner rather than later.

We've mentioned some of the sources of British-Borneo's culture, but it is critical to note that perhapstbc most important source is CEO Alan Gaynor,whose charismatic leadership sets an example.Gaynor participates in the company's many socialfunctions, for example, and is open about bis feelings.At the same time, he is intolerant of subpar perfor-mance and is relentlessly focused on strategic goals.

That Gaynor is a major driver of British-Borneo'scommunal culture, however, is emblematic of one ofthis form's challenges. While a cotnmunal culture isusually difficult to attain and sustain, a strong leadercan tnaiiagc both to powerfully effective ends. Butsbould tbe leader ever leave, the community he or shecreated can easily collapse. Because of its fragility, acommunal culture is also difficult to export. That isthe challenge Gaynor faces today, in fact, as British-Borneo's embryonic operations in Houston, Texas, gothrough a dramatic expansion.

does it? The answer is that the eommunal culturemay be an inappropriate and unattainable ideal inmany business contexts. Our research suggests thatit seems to v ork best in religious, political, andcivic organizations. It is much harder to find com-mercial enterprises in this quadrant. The reason isthat many businesses that achieve the communalform find it difficult to sustain. There are a numberof possible explanations. First, high levels of socia-hility and solidarity are often formed around partic-ular founders or leaders whose departure mayweaken either or both forms of social relationship.Second, the high-sociahility half of the communalculture is often antithetical to what goes on insidean organization during periods of growth, diver-sification, or internationalization. These massiveand complex change efforts require focus, urgency,and performance-the stuff of solidarity in its un-diluted form.

More profoundly, though, there may he a built-intension between relationships of sociability and

solidarity that makes the communal business en-terprise an inherently unstable form. The sinceregeniality of sociability doesn't usually coexist-itcan't-with solidarity's dispassionate, sometimesruthless focus on achievement of goals. When thetwo do coexist, as we have said, it is often in reli-gious or volunteer groups. Perhaps one reason isthat people tend to join these groups after they'vebecome familiar with, and agree with, their objec-tives. (A church's policies, procedures, beliefs, andgoals, for itistance, are made well known to pro-spective members before they join. Once insidethe organization, members find little "strategic"dissension to get in the way of friendship.) By con-trast, when people consider employment at a busi-ness enterprise, they may not know what the orga-nization's beliefs and values are - or they may knowthem and disagree with them but join the organiza-tion anyway for financial or career reasons. Overtime, their objections may manifest themselves inlow-solidarity behaviors.

In their attempts to mimic the virtues of commu-nal organizations, many senior managers havefailed to think through whether high levels of bothsociability and solidarity are, in fact, what theyneed. Again, from our research, it is clear that thedesirable mix varies according to the context. Inwhat situations, then, does a communal culturefunction well?D When innovation requires elaborate and exten-sive teamwork across functions and perhaps loca-tions. Increasingly, high-impact innovation cannotbe aehieved hy isolated specialists. Rather, as theknowledge base of organizations deepens and diver-sifies, many talents need to combine (and combust)for truly creative change. For example, at the phar-maceutical company Glaxo Wellcome, researchprojects are undertaken by teams from different dis-ciplines-such as geneties, chemistry, and toxicol-ogy-and in different locations. Without such team-work, drug development would be much slowerand competitive advantage would he lost.D When there are real synergies among organiza-tional subunits and real opportunities for learning.We emphasize the word real because synergy andlearning are often held up as organizational goalswithout hard scrutiny. Both are good-in theory. Inpractice, opportunities for synergy and learningamong one company's divisions may not actuallyexist or be worth the effort. However, when they doexist, a communal culture unquestionably helps.• When strategies are more long-term than short-term. That is to say, when corporate goals won't bereached in the foreseeable future, tnanagcrial mech-anisms aie needed to keep commitment and focus

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW Novi.mbet-Dctcmbcr 1996 145

CORPORATE CULTURE

high. The communal culture provides high socia-bility to holster relationships (and the commitmentthat accompanies them) and high solidarity to sus-tain focus. Indeed, we have seen communal cul-tures help enormously as organizations have goneglobal-a long and often tortuous process during

There may be a built-in tensionbetween sociability andsolidarity that makes communalcultures inherently unstable.

which strategies have a tendency to be open endedand emergent, as opposed to the sum of measurablemilestones.n When the husiness environment is dynamic andcomplex. Although many organizations claim to bein such an environment, it is perhaps most pro-nounced in sectors like information technology,telecommunications, and Pharmaceuticals. Inthese industries, organizations interface with theirenvironment through multiple connections involv-ing technology, customers, the government, com-petition, and research institutes. A communal cul-ture is appropriate in this kind of environmentbecause its dynamics aid in the synthesis of infor-mation from all these sources.

Changing the CultureThere is clearly an implied argument here that

organizations should strive for a form of communi-ty suited to their environment. Reality is never soneat. In fact, managers continually face the chal-lenge of adjusting their corporate community to achanging environment. Our research suggests thatover the last decade, a numher of large, well-estah-lished companies with strong traditions of loyaltyand collegiality have been forced, mostly throughcompetitive threat, to move from the networked tothe mercenary form. To describe the process astricky does not do it justice. It is perhaps one of themost complex and risk-laden changes a managercan face.

Consider the example of chairman and presidentJan D. Timmer of the Dutch electronics companyPhilips. Once a monumentally successful compa-ny. Philips lost its competitive edge in the mid-1980s and even came close to collapse. Timmerfand many observers) attributed much of the com-

pany's troubles to its corporate culture. Sociabilitywas so extreme that highly politicized cliques ruledand healthy information flow stopped, particularlybetween R&D and marketing. (During this period,many of Philips's new products flopped; critics saidthe reason was that they provided technology that

consumers didn't particularly want.}Meanwhile, authority was routinelychallenged, as were company goalsand strategies. Management's lack ofcontrol allowed many employees torelax on the job. They had little con-cern with performance standardsand no sense of competitive threat.In short. Philips demonstrated manyof the negative consequences of anetworked organization. However,

given the industry's primary success factors-inno-vation, market focus, and fast product rollout-Philips needed a mereenary or communal cultureto stay even, not to mention get ahead.

Timmer attempted just such a transformation,first hy trying to lower managers' comfort level. Heimplemented measurable, ambitious performancetargets and held individuals accountable to them.In the process, many long-serving executives leftthe company or were sidelined. Timmer also con-ducted frequent management conferences, atwhich the company's objectives, procedures, andvalues were clearly communicated. He demandedcommitment to these goals, and those employeeswho did not conform were let go. In this way, soli-darity was increased, and Philips's performance be-gan to show it. '

As performance began to improve markedly,Timmer made efforts to restore some of the compa-ny's sociability, which had been lost during theturnaround - thus moving the company from mer-cenary toward communal. Meetings began to focuson the company's values and on gaining consensus.In short, Timmer was trying to reestablish loyaltyto Philips and connections among its memhers.Timmer was scheduled to retire in October, and itremains to be seen in what direction his successor,Cor Boonstra, will take the company.

Boonstra's challenge is formidable. Once organi-zations try to reduce well-established ties of socia-bility, they can inadvertently unleash a process thatis difficult to control. Unpicking emotional rela-tionships may make solidarity difficult, too. Theresult: organizations can devolve toward an inap-propriate fragmented form. From there, recoverycan be difficult

This precise phenomenon, in fact, can he seen inthe uncomfortable transition now oeeurring in the

146 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-Dec ember 1996

British Broadcasting Corporation. Its director gen-eral, John Birt, has tried to focus the organization-long known for its quality programming and publicservice-on efficiency and productivity. In theprocess, strict performance standards have beenset, and colleagues have had to vie against one an-other for scarcer resources. As sociability has di-minished, talented individuals who once sawthemselves as part of a communal culture haverailed against what they consider target-orientedchanges. Some have decided to stay and stubbornlydefend their own interests; others have chosen toleave. With its communal culture heading towarda fragmented one, the BBC faces no alternative hutto reinvent itself.

How, then, does an organization change its cul-ture from one type to another without wreaking toomuch damage? How does a manager tweak levels ofsociability or solidarity?

Clearly, the tools required to manipulate each di-mension are different. And using them involves un-derstanding why a culture has taken its currentform in the first place-why, that is, a culture pos-sesses its present levels of sociability and solidarity.Neighborhoods, book clubs, and Fortune 100 com-panies can all be friendly for myriad reasons-theexample set by a leader, the personalities of certainmembers, the physical setting of the organizationor its history, or simply the amount of cash in thebank. Likewise, solidarity can arise for many rea-sons. Our purpose here has been not to analyze whyorganizations have different levels of sociabilityand solidarity but to examine what happens totheir culture when they do, and what that meansfor managers who seek satisfied employees andstrong performance. However, before attempting tochange levels of sociability or soli-darity, a manager needs to think a hitlike a doctor taking on a new patient.The patient's past and current condi-tions are not only relevant but alsoeritieally important to assessing thehest future treatment.

Our research shows that to in-crease sociability, managers can takethe following steps:

Promote the sharing of ideas, in-terests, and emotions by recruiting compatible peo-ple-people who naturally seem likely to becomefriends. Before hiring a candidate, for instance, amanager might arrange for him or her to have lunchwith several current employees in order to get asense of the chemistry among them. This kind ofactivity need not be covert. Trying to find employ-ees who share interests and attitudes can even be

stated as an explicit goal. In itself, such an an-nouncement may signal that management seeks toincrease sociability.

Increase social interaction among employees byarranging casual gatherings inside and outside tbeoffice, sucb as parties, excursions-even book clubs.These events might be awkward at first, as em-ployees question their purpose or simply feel oddassociating outside a business setting. One wayaround this prohlem is to schedule such gatheringsduring work hours so that attendance is essentiallymandatory. It is also critical to make these inter-actions enjoyable so that they create their own posi-tive, self-reinforcing dynamic. The hard news formanagers is that sometimes this orchestrated so-cializing requires spending money, which can bedifficult to rationalize to the finance department.However, if the business environment demandshigher levels of sociability, managers can considerthe expenditure a good investment in long-termprofitability.

Reduce formality between employees. Managerscan encourage informal dress codes, arrange officesdifferently, or designate spaces where employeescan mingle on equal terms, such as the lunchroomor gym.

Limit hierarchical differences. There are severalmeans to this end. For one, the organization chartcan be redesigned to eliminate layers and ranks. Al-so, hierarchy has a hard time coexisting with sharedfacilities and open office layouts. Some companieshave narrowed hierarchical differences hy ensuringthat all employees, regardless of rank, receive thesame package of benefits, park in the same lot (withno assigned spaces), and get bonuses based on thesame formula.

How does an organizationchange its culture from one

type to another withoutwreaking too much damage?

Act like a friend yourself, and set tbe example forgeniality and kindness by caring for tbose in trou-ble. At one communal company we know of, man-agement gave a three-month paid leave of absenceto an employee whose young son was ill, and thenallowed her to work on a flexible schedule until hewas completely well. Sociability is increased whenthis caring extends beyond crisis situations-for

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November Dtccmhcr 147

CORPORATE CULTURE

instance, when management welcomes the familiesof its employees into the fold by inviting them tocompany picnics or outings. Indeed, many high-sociahility companies hold Christmas parties forthe children of employees or give each family a spe-cial holiday present.

To huild solidarity, managers can take the follow-ing steps:

Develop awareness of competitors through brief-ings, newsletters, videos, memos, or E-mail. For ex-ample, as Timmer worked to move Philips towardthe mercenary form, he exhorted his managers totake a new, hard look at the company's Japanesecompetitors. Breaking a longtime organizationaltaboo, he praised Japanese quality highly and com-pared Japanese products favorably with those hiscompany made.

Create a sense of urgency. Managers can promotea sense of urgency in their people hy developing avisionary statement or slogan for the organizationand communicating it relentlessly. In the late1980s, for example, Gerard van Schaik, then chair-man of the board of Heineken, took his companyglobal with the internal war cry Paint the WorldGreen. The message was clear, focused, and actionoriented. It worked. Today Heineken is the most in-ternational heer company in the world.

Stimulate tbe will to win. Managers can hire andpromote individuals with drive or ambition, sethigh standards for performance, and celebrate suc-cess in high-profile ways. Mary Kay, the Texas-based cosmetics company, is famous for giving itstop saleswomen pink Cadillacs. In most other orga-nizations, a large check or public recognition-orboth-does the same job. Similarly, an incentivesystem that rewards corporate performance (ratherthan or in addition to unit and personal perfor-mance) underscores the importance of the compa-ny's overall achievement.

Encourage commitment to sbared corporategoals. To do so, managers can move people betweenfunctions, businesses, and countries to reducestrong subcultures and create a sense of one compa-ny. Disney, for example, identifies highfliers-can-didates that show promise-and then moves themthrough five divisions in five years. These individu-als then carry the organization's larger strategic

picture and purpose with them throughout theirlater positions at Disney, pollinating each divisionin the process.

Building the Right CommunitySo far, we have stressed three primary points.

First, knowing how your organization measures upon the dimensions of sociability and solidarity is animportant managerial competence. Second, know-ing whether the company's culture fits the husinessenvironment is critical to competitive advantage.And third, there is no golden quadrant that guaran-tees success. We must stress, however, that ourmodel for analyzing culture and its fit with thebusiness context is a dynamic one. Business envi-ronments do not stay the same. Similarly, organiza-tions have life cycles. Successful organizationsneed a sense not just of where they are but of wherethey are heading. This demands a subtle apprecia-tion of human relations and an awareness that ma-nipulating sociability on the one hand and solidar-ity on the other involves very different challenges.

Finally, we have claimed that patterns of organi-zational life are often conditioned hy factors out-side the organization, such as the competition, theindustry structure, and the pace of technologicalchange. But a company's culture is also governed bychoices. Senior executives cannot avoid or denythis fact. Managers can increase the amount of so-ciability in their staffs by employing many of thedevices listed ahove; similarly, they can manipulatelevels of solidarity through the decisions theymake. In short, these choices have the ability to af-fect what kinds of experiences memhers of an orga-nization enjoy-and don't-on a day-to-day basis.Executives are therefore left with the job of manag-ing the tension between creating a culture that pro-duces a winning organization and creating one thatmakes people happy and allows the authentic ex-pression of individual values. This challenge is pro-found and personal, and its potential for impact onperformance is enormous. Culture can hold hackthe pressures for corporate disintegration if man-agers understand what culture means-and what itmeans to change it. 9Reprint 96605 To order reprints, see the last page of this issue.

148 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November December 1996

Harvard Business Review Notice of Use Restrictions, May 2009

Harvard Business Review and Harvard Business Publishing Newsletter content on EBSCOhost is licensed for

the private individual use of authorized EBSCOhost users. It is not intended for use as assigned course material

in academic institutions nor as corporate learning or training materials in businesses. Academic licensees may

not use this content in electronic reserves, electronic course packs, persistent linking from syllabi or by any

other means of incorporating the content into course resources. Business licensees may not host this content on

learning management systems or use persistent linking or other means to incorporate the content into learning

management systems. Harvard Business Publishing will be pleased to grant permission to make this content

available through such means. For rates and permission, contact [email protected].

Related Documents