Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

The criminal process—The Singapore model

CHAN SEK KEONG*

PARTI

A. Introduction1

The subject of this lecture has troubled the criminal bar and thelaw teachers of the NUS Law Faculty. The criminal process is atthe heart of the criminal justice system. It is not only a subject ofgreat practical importance; it is also a reflection of our ideals andvalues as to the way in which we can accord justice to both theguilty and to the innocent.

As a result of a series of prosecutions during the last 5 years offoreigners for various offences committed in Singapore,2 ourcriminal justice system has become the focus of world attention.It has been praised and condemned at the same time for itsmerits as well as for its failings in unequal measure. For some, itis a model to follow, for others, a model to avoid. But it is amodel which I believe the Singapore public has confidence in;and which has maintained peace, security and good order in the

*

1

2

Attorney-General, Singapore (May 1992-). He writes to acknowledge hisgratitude to Toh Han Li, Deputy Public Prosecutor, for his assistance inpreparing this lecture.

This article is adapted from the 10th Singapore Law Review Lecturedelivered on 26 September 1996.

Flor Contemplation v PP [1994] 3 SLR 834; Michael Fay v PP [1994] 2SLR 154; Johannes van Damme v PP [1994] 1 SLR 246; The WilliamSafire articles; Rajan Pillai’s trial, The Spectator, 15 July 1995; PP v NickLeeson DAC 22050-60/95; AG v Christopher Lingle & 4 Ors [1995] 1SLR 696.

433

434 Singapore Law Review (1996)country. This does not make it better than others, and we shouldnot make such a claim. Each country must have a criminaljustice system which meets its own needs. If the electoratedeserves to have the politicians it elects, equally, a countrydeserves the criminal justice system it has.

Singapore is a relatively crime-free country, especially withregard to crimes of violence, including sexual offences, crimesagainst public and private probity (like corruption) and drugtrafficking. This state of affairs is usually attributed to thepolicies of the Government on crime control, as evidenced bythe laws enacted to suppress these offences and the so-called“drift-net” laws to control even minor forms of anti-socialconduct. Most Singaporeans, I believe, appreciate the safeenvironment they live in and support a criminal justice systemthat is responsible for it. But, of course, not all Singaporeans arepersuaded. Civil libertarians will say that crime control policiesmust not be implemented at the expense of weakening or evenlosing one’s civil liberties. Others even doubt that the strict lawscan achieve their social objectives.3

The Confucian doctrine that the rule of virtue is superior to therule of law is an idealistic view of human nature. It is not knownto have flourished in any society since written history began. Amodern civilised society can only exist and survive under law. InSingapore, even the great virtue of filial piety needs a safety netin legislation.4 But a sense of justice pervades every civilisedsociety, and justice requires that errant members should not bepunished for their transgressions except in accordance with law.Some civil libertarians even insist that no person should even besubjected to any risk of punishment without probable cause.

3

4

Michael Hor: “The Presumption of Innocence—A ConstitutionalDiscourse for Singapore” [1995] SJLS 365, 372 where he writes,“Whether such [statutory] presumptions actually aid the ‘war on drugs’ isquestionable...”

See the Maintenance of Parents Act (Chapter 167B).

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 435In the context of criminal justice under the common law, one

principle stands out. In Ong Ah Chuan,5 Lord Diplock states theprinciple in this way:

One of the fundamental principles of natural justice in the fieldof criminal law is that a person should not be punished for anoffence unless it has been established to the satisfaction of anindependent and unbiased tribunal that he committed it. Thisinvolves the tribunal’s being satisfied that all the physical andmental elements of the offence with which he is charged,conduct and state of mind as well where that is relevant, werepresent on the part of the accused. To describe thisfundamental rule as the “presumption of innocence” may,however, be misleading to those familiar only with Englishcriminal procedure. ... What fundamental rules of naturaljustice do require is that there should be material before thecourt that is logically probative of facts sufficient to constitutethe offence with which he is charged.

In the last few years, beginning with the tenure of the incumbentChief Justice, the criminal process in Singapore has begun a newphase of development of its basic principles through judicialreconsideration and refinement of case law principles and the re-interpretation of statutory provisions. This came about as a resultof the large number of capital cases that have come on for trialand on appeal in the last few years and also the practice of theChief Justice himself to hear all criminal appeals from theSubordinate Courts to the High Court. More appeals mean morenovel points of law, more arguments, more dicta and moredecisions. Another contributing factor is the greaterprosecutorial awareness of the need to refine and improve thecriminal process. This awareness has been translated intoappeals and referrals of points of law by the Attorney-General tothe Court of Appeal for determination. Here, I should explainwhy there have been more frequent interventions by theAttorney-General of this nature. Where the accused is convictedfor an offence tried in the High Court, the Public Prosecutorcannot appeal and therefore has no opportunity to seek to correct

5 [1981] 1 MLJ 64.

436 Singapore Law Review (1996)any pronouncements on a point of law which, although notaffecting the decision in the case, may have adverseconsequences for prosecutions in the Subordinate Courts. Morethan 90% of criminal prosecutions are processed in these courts.The last time a district judge decided not to follow a statement oflaw made by the High Court on the ground that it was made perincuriam, he was roundly chastised by another High Court Judgeon appeal.6 As state prosecutors, we have an obligation toexercise vigilance in ensuring that the criminal process is not,through default, made more difficult for us in the successfulprosecution of the guilty accused.

Currently, it is not unfair to say that the criminal bar is lessconcerned about the needs of an efficient and effective criminalprocess than about how such a process would affect itsprofessional role. It cavils at so-called “driftnet” laws, statutorypresumptions and the effects of some judicial decisions which,undoubtedly, reduce the armoury of procedural and otherdefences available in the defence of the accused. Under ouradversarial system of trials, defence counsel are not concernedwith the factual guilt of the accused. What is relevant is whetherthe prosecution is able prove its case beyond reasonable doubt.Every law or judicial decision that weakens this principle isviewed with concern, and even despair. There was a time whensome members of the criminal bar even believed, through thepower of anecdotal evidence spreading through the Bar room,that the Chief Justice had decided to enhance sentences onappeal in order to deter appeals, and not because he decided eachcase on its merits. The empirical data actually contradicted thisbelief and showed that most of the sentences were enhanced onappeals by the prosecution and the others were enhancedbecause they were manifestly inadequate.

However, for all their concerns, the criminal bar, as a whole,has not been able to express their views through well-argued orreasoned writings, as contrasted with the measured reactions ofsome law teachers as expressed in the academic journals. Thereappears to be a growing mood among the teachers of criminal

6 Goh Cheng Chuan v PP [1990] 3 MLJ 401 per Thean J (as he then was).

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 437law and procedure in the NUS Law School that our criminalprocess is now tilted against the accused, and that its underlyingcommon law traditions and values are being uprooted slowly butsurely in favour of a model which accepts a high risk of theinnocent accused being charged and convicted. If these concernshave substance, then we should correct this state of affairs assoon as possible. But I believe that the concerns of the criminalbar and of the law teachers are exaggerated. There is much in thecriminal process that protects the interests of the accused frombeing wrongfully convicted, especially if he is innocent.Protecting the innocent accused is a primary objective of thecriminal process and those who operate it, especially the judges.But, it has to be recognised that it is simply not practical to try toestablish a process that ensures that no innocent person will everbe convicted. In theory, such a process can be established but itwill only become a charter for murderers, rapists, robbers, andother criminals, etc to act with impunity.

B. The function of the criminal process

What is the criminal process? It is the aggregation of all theactivities “that operate to bring the substantive criminal law tobear (or to avoid bringing it to bear) on persons suspected ofhaving committed crimes.”7 It normally begins with thereporting of a crime to the police and ends with the finaldisposition of the case against the accused for the commission ofthat offence. This process covers the pre-trial investigation bythe police, the evaluation of the investigation papers by theprosecutor, the decision to proceed or not to proceed, the chargeto prefer, the arrest of the accused, his preliminary appearancesin court with or without counsel, his release on bail or furtherremand, the disclosure or discovery of prosecution evidence, theplea bargain, if any, the preliminary inquiry for offences to betried in the High Court, the trial of the accused and the post-trialprocesses of mitigation, sentencing and appeal if he is convicted.

7 Herbert Packer, “Two Models of the Criminal Process” (1964) 113 Univof Pennsylvania Law Review 1.

438 Singapore Law Review (1996)The accused is regarded as the important actor in the entireprocess. The legal process as developed is still predicated on theaccused’s rights, eg, the right to a fair trial, the right, if he isinnocent, not to be convicted, amongst his other rights.Traditionally, the victim is regarded as the unfortunate cause ofthe accused’s temporary predicament.

What is the criminal process for? It is to process crimes withinan established legal system in accordance with procedures laiddown by the law so that the guilty can be punished for theircrimes. In Winston Brown,8 Steyn LJ (as he then was) said:

The objective of the criminal justice system is the control ofcrime, but in a civilised society that objective cannot bepursued in disregard of other rules.

The process requires a trial in accordance with the fundamentalrules of natural justice. It is arguable that in principle these rulesdo not require that the criminal process must favour the accused,in whatever degree. But, as developed, they require the court togive him every consideration so that if there is a reasonabledoubt about his guilt, he is to be acquitted. It is also arguablethat the rules do not prohibit the criminal process frompreferring crime control in the larger interest of the community,so long as they are not obviously unfair to the accused.9 Whatthat balance should be, between community needs and individualrights in the criminal process, is determined by the ideologicaland social goals of the government of the day. If anything hasbeen made clear in Singapore, it is that crime control has alwaysbeen and is a high priority on the Government’s action agenda.The efficient and effective maintenance of law and order inSingapore is considered absolutely essential to its social,economic and political well-being. The criminal process plays acentral role in the criminal justice system to facilitate theachievement of those goals.

8

9[1995] 1 Cr App R 191.

Lord Diplock in Haw Tua Tau [1981] 2 MLJ 49 at 50.

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review LectureC. Detention without trial

439

Indeed, the Government’s credo that the strict maintenance oflaw and order is so vital to the welfare of its citizens that it wasprepared to discard the established trial process and itsapplication of due process norms in two areas of criminalactivities and substituting in its place detention without trial.These are (1) unlawful activities of secret societies and othercriminals under the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act,and (2) drug addiction under the Misuse of Drugs Act. Detentionwithout trial is the most efficient and most effective form ofcrime control that can be devised. It is the weapon most fearedby secret societies. That is why Hong Kong triad societies do notoperate in Singapore. If the most desired standard of proof in thecriminal process is proof beyond any doubt, that standard isachieved under the Misuse of Drugs Act because no person isdetained unless a blood test shows the presence of a controlleddrug, thereby proving drug consumption beyond any doubt. If anacceptable norm of the criminal process is that there should be atrial or hearing before an independent and unbiased tribunalbefore a person’s liberty can be taken away, the post-detentionhearing provided for criminal detainees is a fair approximationof such a hearing, as the detainee is entitled to make his defenceto a review board, consisting of practising lawyers from theprivate sector, which then recommends on the evidence placedbefore the members whether the detainee should be released ordetained. It can also be argued that the detention without trial isnot obviously unjust or unfair to criminals who have the powerand means to intimidate witnesses from testifying against themin court. The other law is arguably not unjust to drug addictssince it is intended to treat and rehabilitate them so that they canbecome useful citizens. Civil libertarians cannot accept suchlaws, whatever their practical justifications, for the reason, interalia, that such laws are open to abuse. There is a large degree ofpublic acceptance of these laws in Singapore. However,confidence in the justice of such laws can only be maintained ifthe executive uses them, and is seen to do so, for the purposescontemplated by Parliament. The Attorney-General has a vital

440 Singapore Law Review (1996)function in the proper exercise of the particular power ofdetention under the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Actas he has to consent to it.

D. Is the Singapore model efficient?

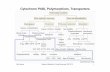

In order to have a better understanding and appreciation of therole of the criminal process in Singapore and to considerwhether its existing framework is efficient to achieve itsdesignated purpose, it is useful to measure it against two modelswhich have been postulated by an American academic, ProfessorHerbert Packer, in his article entitled “Two Models of theCriminal Process”.10 He refers to them as “The Due ProcessModel” and “The Crime Control Model”. What follows are verybrief descriptions of the models.

E. Crime control model

The value system of the crime control model is:

... based on the proposition that the repression of criminalconduct is by far the most important function to be performedby the criminal process. The failure of law enforcement tobring criminal conduct under tight control is viewed as leadingto the breakdown of public order, leading to law-abidingcitizens being victimised by law-breakers.

If this happens, the citizen’s security of person and property issharply diminished, and therefore, so is his liberty to function asa member of society. The criminal process is a positiveguarantor of social freedom. Crime control demands a high rateof conviction, and places a high degree of trust in the efficiencyof administrative procedures in discovering the facts of thecrime. The successful conclusion of the crime control model isnot conviction by the adjudicative act of the court but the plea ofguilty. Cases must be processed quickly and with finality. Theapplication of administrative expertise, primarily that of thepolice and the prosecutors, should result in an early

10 Supra, n 7.

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 441determination of probable guilt or innocence. The probablyinnocent are screened out. The probably guilty are passedquickly through the remaining stages of the process. Accordingto Packer, the key to the operation of the model is thepresumption of guilt. This is not the opposite of the presumptionof innocence which is the polestar of the due process model.Once a determination is made that there is enough evidence ofguilt, which may take place as early as the time of arrest, he is tobe treated as probably guilty.

If there is confidence in the reliability of informal,administrative fact-finding activities that take place in theearly stages of the criminal process, the remaining stages canbe relatively perfunctory.

The presumption of guilty is an expression of that confidence. Itis basically a prediction of outcome. It is descriptive and factual.In contrast, the presumption of innocence is normative and legal.It means that until the accused is found guilty by a court, he is tobe treated, for reasons which have nothing whatever to do withthe probable outcome of the case, as if his guilt is an openquestion. It is a direction to the courts to ignore the amount ofevidence amassed against the accused. The crime control modelresembles an assembly line in its disposition of cases. Its credois justice with efficiency.

F. Due process model

The due process model looks like an obstacle course. Its credo ispreventing any innocent accused person from being subject tothe process. Each of its successive stages is designed to presentformidable impediments to carrying the accused further along inthe criminal process.

Due process ... starts from the proposition that it is better to letten guilty men go free than to convict a single innocentdefendant.11

11 David Rose, “The Collapse of Criminal Justice” (1966).

Its ideology is not the opposite of the crime control model as italso recognises the desirability of repressing crime. Its ideologyis composed of a complex of ideas, but essentially it is to giveprimacy to the rights of the individual against those ofcommunity. It recognises the fact that people make mistakes.The police can and do abuse their powers and extractconfessions by various means. Witnesses can be biased. Packersays that the aim of the due process is at least as much to protectthe factually innocent as it is to protect the factually guilty. Civilliberties are emphasised and the protection of the integrity of thelegal system is accorded high priority. So, all evidence obtainedafter the initial wrongful arrest must be rejected, even if true.Any breach of procedural rules is an abuse of process whichterminates the prosecution. At the appeal stage, due processideology says convictions, even of factually guilty people, mustbe quashed if there turns out to have been what English lawterms a “material irregularity”. Proof of guilt must be beyondany doubt by the prosecution and all the essential elements of theoffence must be proved according to that standard. A convictioncan be reversed if the appellate court feels that it is not safe toconvict him.

In summary, under pure crime control the conviction ratewould be near to 100 per cent as all accused persons not weededout before trial are factually presumed to be guilty, until theyprove the contrary. Pure due process, on the other hand, requiresa system in which conviction demands proof beyond any doubtat all, rather than the less demanding test of proof beyondreasonable doubt.

G. The Singapore model—Present condition

If we could start all over again to construct a criminal processmodel, we would begin by identifying its ultimate goal. Aspresently advised, that goal would be a high rate of conviction ofthe factually guilty accused. This would require the adoption ofmany of the features of Packer’s crime control model if theSingapore model is to maintain that degree of efficiency toachieve that goal. However, no civilised government can be

442 Singapore Law Review (1996)

totally insensitive to potential miscarriages of justice in thecriminal process. Hence, the process must contain rules andprocedures which can prevent and correct such injustices.

Do we have such a model? What we have is a modelincorporating many features from both of Packer’s models. It isdifficult to say where there is a proper balancing of the twointerests, or where the scale is tilted. Is it efficient? The answeris probably yes, if the following measures are used: (a) thepercentage of cases which are disposed of through guilty pleas,(b) the insignificant number of cases where miscarriages ofjustice have been raised in public; and (c) the excellent state ofour social condition in terms of crime and punishment. However,it is only within recent memory that Singapore has been becomeand seen to be a relatively crime-free country. This might nothave been the case in the past.

H. English common law influence

In the recent past, the criminal process of has been undulyinfluenced by English common law principles applicable to acriminal trial in England, in particular jury trials. Our criminalprocess is derived from Indian statutes corresponding to 3current enactments, the Evidence Act, the Criminal ProcedureCode and the Penal Code. These Indian statutes consolidated theprinciples of evidence and procedure applicable in England,subject to certain some modifications which affected certainrights available to the accused at common law, eg the privilegeagainst self-incrimination, the principle of proof beyondreasonable doubt, etc. The criminal law and procedure ofEngland applied to Singapore by virtue of the Second Charter ofJustice 1826. Act No 74 of 9 Geo IV was enacted in 1828 toimprove the criminal procedure. In 1873 we jettisoned Englishcriminal law in favour of Indian criminal law when the PenalCode was introduced into the Straits Settlements. The firstEvidence Ordinance, based on Indian legislation, was enacted in1893. In 1900, a code of criminal procedure was enacted byOrdinance 21 of 1900 which did not come into force. It wasrepealed and re-enacted by Ordinance 10 of 1910 which did

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 443

come into force. The existing Code is a re-enactment of thisCode as amended from time to time.

The first important change came immediately after Singaporeachieved self-government in 1959. The new government did notbelieve in the efficiency or efficacy of juries in civil andcriminal trials. Nevertheless, it acted cautiously in retaining jurytrials for capital offences. By 1969, the government becameconvinced that juries in Singapore were unable or reluctant toadminister criminal justice according to law. Accordingly, thejury trial for capital cases was abolished and replaced with atwo-judge court. The second important change came in 1960when pre-trial voluntary confessions made by an accused toinspectors of police were made admissible.12 The so-calledJudges’ Rules in the form of Schedule E was also introduced togovern police questioning of accused persons. Prior thereto, onlyconfessions made before magistrates were admissible. The thirddevelopment consisted of a group of amendments enacted in1973 and 1976 which made admissible all statements made to orin the presence of any police officer of or above the rank ofsergeant (1973) and which also allowed the courts to makeadverse inferences against the accused if he (a) during pre-trialquestioning, failed to state his defence, and (b) during the trial,failed to testify under oath after his defence is called. It isprobable that this group of amendments became the mosteffective means of crime control in Singapore. The fourthsignificant development, surprisingly, came from the combined

The judicial definition of when a statement is voluntarily made is a wideone. In Mohd Ali Bin Burut & Ors v PP [1995] 2 AC 579, an appeal to thePrivy Council from Brunei, the accused persons had given confessions topolice officers. It was not in dispute that at the time the accused personsgave the confessions they were not manacled and hooded (the “specialprocedure”), but it was also not in dispute that a few days earlier they hadbeen manacled and hooded. The Board held that this amounted tooppression as nothing was done by the police during the recording of theconfessions to dispel the implied threat of further interrogation at whichsuch special procedure would be applied to them. The Board accordinglydeclared that the confessions were not voluntary and quashed theconvictions of the accused persons.

12

444 Singapore Law Review (1996)

effect of 3 Privy Council decisions, viz, Yuvaraj,13 Jayasena14

and culminating in Haw Tua Tau.15 These changes collectivelyhad a substantial effect in improving crime control in Singapore.There were other statutory amendments which lightened theprosecution’s burden in securing convictions, eg in 1976 whenany requirement that a trial judge had to warn himself beforeconvicting on the uncorroborated evidence of an accomplice wasabrogated. These amendments impacted on isolated cases which,unlike the 1976 amendments, impacted on all suspects andaccused persons. It is not possible to discuss here all thesedevelopments. A few are discussed below, starting with thePrivy Council decisions because there are lessons to be learnttherefrom.

I. The case of Yuvaraj

In Yuvaraj, the issue was the standard of proof required to rebutthe presumption in section 3 of the Prevention of Corruption Act1961 (Malaya) that a public officer who receives a gratificationis deemed to have received it corruptly “unless the contrary isproved”. The expressions “proved”,16 “disproved”17 and “notproved”18 have been statutorily defined since the EvidenceOrdinance was applied to Malaya. Under section 105, the burdenof proving the existence of circumstances bringing the case

[1970] AC 913.

[1970] AC 618.

[1981] 2 MLJ 49.Section 3(3) reads: “A fact is said to be ‘proved’ when, after consideringthe matters before it, the court either believes it to exist or considers itsexistence so probable that a prudent man ought, under the circumstancesof the particular case, to act upon the supposition that it exists.”

Section 3(4) reads: “A fact is said to be ‘disproved’ when, afterconsidering the matters before it, the court either believes that it does notexist or considers its non-existence so probable that a prudent man ought,under the circumstances of the particular case, to act upon the suppositionthat it does not exist.”Section 3(5) reads: “A fact is said to be ‘not proved’ when it is neitherproved nor disproved.”

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 445

13

14

15

16

17

18

within any special exception or proviso contained in any lawdefining the offence is on him who relies on thesecircumstances, and the court “shall presume the absence of suchcircumstances.” The Federal Court referred this question to thePrivy Council for consideration:

Whether in a prosecution under section 4(a) of the Preventionof Corruption Act, 1961, a presumption of corruption havingbeen raised under section 14 of the said Act the burden ofrebutting this presumption can be said to be discharged by adefence as being reasonable and probable or whether thatburden can only be rebutted by proof that the defence is onsuch fact (or facts) the existence of which is so probable that aprudent man would act on the supposition that it exists.(Section 3 Evidence Ordinance.)

The Privy Council did not think that there was any relevantdifference in practical effect between the tests stated by theFederal Court. The Malayan and Indian authorities on the issuewere conflicting and the English authorities were also not clear.In Wong Chooi,19 Azmi CJ said that the burden on the accusedwas only a slight one. Lord Diplock, delivering the PrivyCouncil’s advice, held that although the definition of “proved”did not specify the quantum of proof, common sense dictatedthat the degree of probability of the existence or non-existenceof any fact must depend on the nature of the proceedings. If thefinding of a fact results in a conviction, public policy demandsthat the degree of probability must be beyond reasonable doubt.If the finding of a fact results in an acquittal, there can be nogrounds in public policy for requiring that an exceptional degreeof certainty as excludes all reasonable doubt that the fact doesnot exist. In other words, the burden on the accused to rebut thepresumption is on the balance of probability. Prior to thisdecision, local case law was to the effect that the burden was nomore than an evidential burden.

[1967] 2 MLJ 180, 181.

446 Singapore Law Review (1996)

19

J. The case of Jayasena

In Jayasena, an appeal from Ceylon decided 3 months afterYuvaraj, the issue was whether, in a murder charge to which theright of self-defence was pleaded, the accused had to prove thedefence on a balance of probability or on the balance ofevidence. The appellant relied on English, Indian and Malayanauthorities which had held that the accused had only to dischargethe evidential burden, and not the persuasive burden. LordDevlin, delivering the opinion of the Privy Council, held that thestandard of proof was on a balance of probability and not on thebalance of evidence because of the compelling language ofsections 3 and 105 of the Evidence Ordinance. Lord Devlin heldthat the word “proved” in section 3 meant proof as defined andnothing less. Prior to this decision, the local courts hadinterpreted these sections to refer only to the evidential burden.

K. Local reaction to statutory changes

Thus, it would appear that the draftsman of the Indian PenalCode and the Indian Evidence Act had effected revolutionarychanges to the burden of proof in the trial process with respect tocodified common law offences without the local judges realisingit. Why was the established principle of proof beyond reasonabledoubt modified for the Indian criminal justice system? It maywell be that this particular due process norm which is the goldenthread of English criminal law was found unsuitable to a societythat was not as developed as England then was, or that perhapsunlawful killings were rampant in India, as they probably were,and so had to be controlled by shifting the legal burden ofproving justification on any accused who had killed somebody.Whatever the reasons, these provisions were also found suitablefor application to the Straits Settlements.

However, the local courts did not understand these provisionsas having modified the common law. This state of affairs wouldhave continued but for the perceptive realism of the Court ofCriminal Appeal of Ceylon in Chandrasekera,20 which decision

See R v Chandrasekera (1942) 44 NLR 97.

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 447

20

the Privy Council in Jayasena found irreproachable. In Yuvaraj,the law on the point was corrected only when a wrongly-framedquestion of law was referred to the Privy Council. Thus,Singapore had for more than 100 years a modified principle ofproof which reduced the opportunities for killers literally to getaway with murder, and also in the laws creating other offences,but it was understood and applied by the courts as if it were thepure principle of proof beyond reasonable doubt. If this analysisis correct, and if you take Haw Tua Tau21 into account as well,then the record of the local judiciary in relation to crime controlwas not inspiring at all. It could be said that the guilty accusedand their counsel had the best of times, whilst the prosecutors,representing the public interest, had the worst of times. The pastmay be the past, but we should ask ourselves how this couldhave come about. I would like to suggest the combined effect oftwo probable causes.

L. Structure of English law

The first has to do with the structure of English law. The basiclaw of England, as of Singapore, is English common law.English legislation, like Singapore legislation, is drafted by thedraftsman and enacted by Parliament on the foundation of thecommon law. In consequence, legislation is invariablyinterpreted by the judges as glosses on the common law becauselegislation is only necessary when the common law is deficient.For this reason, an established canon of construction is thatstatutes are not intended to repeal or modify the common law,unless it is expressed as such or a necessary implication can beread from it. One of the most fundamental principles in thecriminal law is the principle of proof beyond reasonable doubt,which is always the burden of the prosecution to discharge. Thisis the legal or persuasive burden, which cannot be shifted to the

In Haw Tua Tau, supra, n 15, the Privy Council held that the prosecutionhad only to prove a prima facie case at the conclusion of its case in orderthat the defence be called. Prior to that, the local courts required theprosecution to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt before the defencecould be called.

448 Singapore Law Review (1996)

21

accused. The accused need only to show a reasonable doubt thathe is guilty. This is the evidential burden which the accused hasto discharge. It is not to prove or disprove anything but to raise areasonable doubt. It is a high standard of proof which isdescribed by Suffian J in Mat22 as follows:

The correct law for Magistrates to apply is as follows. If youaccept the explanation given by or on behalf of the accused,you must of course acquit. But this does not entitle you toconvict if you do not believe that explanation, for he is stillentitled to an acquittal if it raises in your mind a reasonabledoubt as to his guilt, as the onus of proving guilt liesthroughout on the prosecution. If upon the whole evidence youare left in a real state of doubt, the prosecution has failed tosatisfy the onus of proof which lies upon it.23

The second cause has to do with legal education and professionalexperience. The local courts did not pay much attention to thedefinition of “proved”, probably, on account of the common lawmindset of the judges, all of whom were English trained. Thiscan be seen from the many decisions on the law of principles ofproof which did not even refer to the Evidence Act. They couldnot imagine that Sir James Stephens could have modified theprinciple of proof so radically as to shift the persuasive burdento the accused to prove anything in any offence. The influence ofthe judges’ common law mindset cannot be exaggerated.Generations of judges and lawyers in Singapore and Malaya

(1963) MLJ 263.

Contrast this with Denning J’s statement in Miller v Minister of Pensions[1974] 2 All ER 372 where he commented on what the standard “beyondreasonable doubt” meant at 373:

It need not reach certainty, but it must carry a high degree ofprobability. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt does not mean proofbeyond a shadow of a doubt. The law would fail to protect thecommunity if it admitted fanciful possibilities to deflect the course ofjustice. If the evidence is so strong against a man as to leave only aremote possibility in his favour which can be dismissed with thesentence “of course it is possible, but not in the least probable,” thecase is proved beyond reasonable doubt, but nothing short of that willsuffice. [Emphasis added.]

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 449

22

23

have imbibed the traditions, ethos and values of the Englishjudiciary and of the English Bar. Law was not taught locallyuntil 1957. Even then, criminal law and procedure, as a lawsubject, was taught by lawyers from the same tradition. It istherefore not surprising that the Evidence Act and the CriminalProcedure Code were viewed as nothing more than codificationsof common law principles. The influence of English due processthinking persists until today, in the judiciary, in the criminal barand in the NUS Law School. This phenomenon was not confinedto Singapore and Malaysia. G Peiris wrote in 198024 as follows:

So pervasive was the influence of an equivalent objection [thatonly the evidential burden should be assumed by an accused inregard to defences as lawful excuse and lawful authority],deeply rooted in traditions of the English common law, that, inthe formative stage development of the case law injurisdictions governed by the codes of evidence founded onthe Indian Evidence Act, the courts of some South Asianjurisdictions showed themselves inclined to whittle down theclear effect of definitions contained in mandatory statutoryprovisions in order to make the codified system accord withthe values and attitudes of the English common law, and, inparticular, with the refusal of that system to impose on theaccused the legal burden in respect of any defence other thaninsanity. The reasoning of these courts involved, necessarily,strained and tortuous construction of the language used in theapplicable codes of evidence. The interpretation of codesbased on the Indian Evidence Act in substantial conformitywith the postulates of the English common law derivesimplicit support from some recent observations of PrivyCouncil, the setting of the Malaysian law of evidence (in PP vYuvaraj).

The attitude of the Sri Lankan courts, which have consistentlydeclined to import into the law of Sri Lanka principles ofEnglish law incompatible with:

“The Burden of Proof and Standards of Proof in Criminal Proceedings: AComparative Study of English and a Codified Asian System” (1980) 22Mal LR 66, 105-106.

24

450 Singapore Law Review (1996)

the clear, definite and unequivocal language employed in a SriLankan enactment, presents a striking contrast. In keepingwith the premise that, in their natural role of moulding andinterpreting the law, the Sri Lankan courts must makeallowance for the complete dimension of statute law in forcein the jurisdiction without distorting it as a means of statutoryprovisions within the conceptual framework of law, the courtsof Sri Lanka, have evolved a body of largely self-containedevidentiary law which, for the most part, is cohesive and virile.

M. The abolition of the jury trial

The abolition of jury trial should have had a profound effect onthe rules of procedure and evidence relevant to trial process, asmost of the exclusionary rules of evidence were formulated forsuch trials. The accused had to be protected from the frailties ofjurors in evaluating evidence. They could not be trusted toevaluate evidence objectively and they could not determine whatweight should be given to prejudicial evidence. Hence probativeevidence was excluded from their purview if the judge thoughtthat its value was outweighed by its prejudicial effect. Thisconcern is much less important in bench trials conducted byjudges who have spent their entire professional careers in courtand who have been conditioned to evaluate facts and argumentsobjectively. Moreover, unlike jurors, judges have to give reasonsfor their findings of fact. Egregious errors in fact evaluations andfindings are generally detectable and can be corrected on appeal.

But if you read the reported judgments of the courts in the last30 years, you would have the impression that save for theabsence of the jury, nothing else in the criminal process haschanged. That is largely true. There seems to be little or noawareness that bench trials should not be subject to exclusionaryrules devised for jury trials. Surprisingly, there is also littleacademic writing locally on this subject. The state prosecutorswould also appear to have failed to take the necessary initiativesto argue for modification. The criminal bar cannot be faulted for

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 451

keeping silent. In 1981 Lord Dip lock adverted to the change inOng Ah Chuan25 when he said:

Supra, n 5 at 71.

[1995] 2 SLR 349, 363.

(1934) 38 CWN 659.

25

26

27

452 Singapore Law Review (1996)

Observance of the rule [that the prosecution must prove itscase beyond a reasonable doubt] does not call for theperpetuation in Singapore of technical rules of evidence andpermitted modes of proof of facts precisely as they stood at thedate of the commencement of the Constitution. These arelargely a legacy of the role played by juries in theadministration of criminal justice in England as it developedover the centuries. Some of them may be inappropriate to theconduct of criminal trials in Singapore ...

This passage was not addressed to bench trials in particular, andthat perhaps explains why it has been all but forgotten. However,the passage is even more appropriate in the context of benchtrials than in the context of determining what the fundamentalrules of natural justice are. But change can now be seen, albeittentatively, and in small steps. In Lee Yuan Kwang,26 in dealingwith the issue as to whether a miscarriage of justice had occurredwhere the trial judge had read the impugned statement of one ofthe accused before the voir dire had been completed, the ChiefJustice said:

Nayeb Shana (Shahana)27 was cited by counsel to support thecontention that the trial judge had to decide on the question ofvoluntariness before proceeding with the impeachmentproceedings. It must be noted that Nayeb Shana’s case wasmade in the context of jury trials. The judge, whose soleprovince was to decided questions of law, would have had aduty to exclude inadmissible evidence from the considerationof the jury. It is less compelling to adhere to such rigiddelineations in the present day context where jury trials havelong since been abolished. The trial judge has the duty todecide on both the law and the facts. He is also expected to beable to exclude inadmissible or prejudicial evidence fromconsideration. In the prevailing climate of criminal practice of

procedure, it may have been procedurally improper for thetrial judge to have looked at the statements in their entirety inthe course of the voir dire. Nevertheless, such proceduresrequiring that the trial judge be shielded from statements, orportions of statements, the voluntariness of which may bedisputed, are relics from jury trials of days of yore. They holdno real significance in present-day trials where judges areequally competent to decide on disputes of fact as well as thelaw. Ultimately, the main question is whether, having heardthe evidence, the trial judge had properly directed himself infinding that the statements had been voluntarily made. In thepresent case, the record and the grounds of decision indicatedthat he was always mindful of the importance of the issue ofvoluntariness of the statements. There was also no indicationfrom our perusal of the record that the trial judge had allowedhimself to be unduly prejudiced by the contents of thestatements. We are satisfied that there was no materialirregularity in the conduct of the impeachment proceedingswhich would occasion a failure of justice.

[1977] 1 MLJ 171.28

Now that the reality of a bench trial has been recognised, weshould see more developments in this area either throughjudicial modification of jury related principles or legislation inareas where judges fear or refuse to tread. But a clear judicialtrend has yet to be established. I will cite a few examples of thecontinuing influence of jury principles in bench trials.

N. The trial within a trial

In a jury trial, where the accused objects to any evidence whichthe prosecution wishes to adduce against him, usually aconfession, a trial within a trial is held to determine itsadmissibility. However, until it is admitted in evidence, the juryis not allowed to know what the accused has said, as it could beprejudicial to the accused. Admissibility, being a question oflaw, is decided by the judge in the absence of the jury. Hence,the rule that evidence adduced in a trial within a trial is notrelevant to the trial on the main issue as to whether the accusedis guilty. In Lim Seng Chuan,28 the Singapore Court of Criminal

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 453

It seems to us that fairness to the accused, which is afundamental principle of the administration of justice, requiresthat a trial within a trial ought to be considered a separate orcollateral proceeding. In the course of a trial within a trial,evidence may be given which would be inadmissible evidenceon a charge against the accused but may be relevant to theissue to be decided at the trial within a trial. In such a situationit would be grossly unfair to the accused if the true principle isthat evidence called at the trial within a trial is before the courtfor all purposes.

The reasoning set out in this passage should not apply in a benchtrial where the judge has heard all the evidence. In that case, theevidence that was rejected by the court, although not relevant toadmissibility, was highly relevant to the main issue. The abovepassage does not explain the unfairness of admitting it. The truereason is found in the next passage, which reads:

Appeal upheld this rule and reversed the conviction for murderof the accused which apparently was based solely on theevidence of a prosecution witness who had testified in a voir direon a matter which was not relevant to the admissibility of theconfession in question. The Court said:

Conversely, in the course of a trial within a trial evidence maybe given which may be relevant and admissible evidence onthe charge against the accused but would not be relevant onthe issue to be decided at the trial within a trial. In such asituation the accused or his counsel might well decline tochallenge such evidence in the justifiable belief that it couldnot adversely affect the accused on the issue to be decided atthe trial within a trial.

But, of course, if the true principle were otherwise, defencecounsel would have no excuse for not cross-examining thewitness. Treating the two trials as separate would certainly makefor a tidier trial overall, but tidiness in this respect has nothing todo with the fairness of the criminal process, and in any case thesame result can be achieved by better management of the issuesat the trial.

Numerous sub-principles have been laid down by the courts todetermine the admissibility of such evidence, depending on

454 Singapore Law Review (1996)

whether the statement is ruled admissible or otherwise: seeWong Kam-Ming.29 The complexities of the law in this area canbe seen in Goh Joon Tong.30 in that case, two voir dires wereheld in respect of the statements of A and his co-accused B. Thetrial judge postponed his determination on the admissibility ofA’s statement until he had concluded the voir dire on B’sstatement, which A gave evidence. The trial judge then took intoaccount A’s credibility in B’s voir dire and admitted A’sstatement. The Court of Appeal held (a) that postponing such adecision to the conclusion of a voir dire should not be done, if adecision could be reached, but it was not an immutable rule thatthe ruling be made immediately at that point of time; and (b)that, applying Lim Seng Chuan, one voir dire should be insulatedfrom another voir dire, and therefore evidence adduced in onewas not admissible in the other. The Court went on to hold thatthe error of the trial judge had not prejudiced A as there wasother evidence that his statement was voluntary.

One cannot help but sympathise with the trial judge. He citedauthorities which stated that a court is not to close its eyes toevidence relating to the voluntariness of a statement after it hasbeen admitted in evidence. He made the following statementwith which the Court of Appeal disagreed:

[1980] AC 247.

[1995] 3 SLR 305.[1982] Crim LR 682.

29

3031

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 455

The next question is whether such evidence should berestricted to evidence supporting inadmissibility, and notevidence to the contrary. That should not be so. Justice mustbe administered equally for the defence as for the prosecution;it is not good enough to doff one blinker and wear the other.All evidence relevant to the issue, whether in favour ofadmission or exclusion, should be considered.

The purpose of a trial within a trial should be reconsidered.Where the judge is the trier of law and of fact, treating a voirdire as a separate trial serves no purpose. In England, theDivisional Court (Lord Lane and Woolf JJ) decided in F (AnInfant) v Chief Constable of Kent31 that incidental matters

should be decided as separate issues and not as trials withintrials; and consequently there was no need for evidence to berepeated after the issue of admissibility had been determined. Inreality, a judge does not need to read an impugned statement toknow it is adverse to the accused.32 As regards the evidenceadduced at the voir dire itself, there are practical difficulties inexcluding the evidence, if it is relevant to the main issue. Firstly,the judge has heard the evidence. Secondly, what the accusedsays in the trial within a trial may be most relevant to the issueof his credibility or even guilt in the main trial. He may giveconflicting testimony on the same issue. Indeed, he may evenhave lied to render his confession inadmissible. Thirdly, itrequires the prosecution to cross-examine the accused again onthe same issues if they are relevant. We need to establish a set ofcoherent principles which conform to the realities of a benchtrial which the Chief Justice has recognised. It would increasethe efficiency of the criminal process if evidence adduced at thetrial of a collateral issue a trial is admissible in the trial of themain issue.

N. Evidence of disposition and similar fact

In a jury trial relevant evidence may be withdrawn from the juryif the judge considers that its prejudicial effect outweighs itsprobative value. There are a number of situations where thisprinciple is applicable. This principle should have little or norelevance in bench trials as the judge can simply give whateverweight is appropriate to the evidence. There is no need for ajudge to go through the formal process of declaring the evidenceinadmissible. But our courts continue to deal with such evidencein this fashion. For example, in Tan Chee Kieng,33 the trialjudge allowed the prosecution to go into the record of theaccused’s admission of previous drug transactions unconnected

See however the unique case of PP v Zeng Guoyuan, MAC 2699/96 wherethe unrepresented accused, an acupuncturist, inexplicably challenged thevoluntariness of his statements to the police even though they were notadverse to him.

[1994] 2 SLR 834.

32

33

456 Singapore Law Review (1996)

with the offence in the trial. He made it clear in his judgmentthat he had not taken the said admission into account in decidingwhether or not the charge had been proved. He could simplyhave stated that evidence of the previous transactions hadinsufficient probative value to corroborate the other evidence.The Court of Appeal spoke in terms of admissibility when itsaid:

[1989] 2 HKLR 97.

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 457

... the evidence of general disposition occasioned no injustice.It should be remembered that, unlike a trial with a jury, ajudge trying a case without a jury is unlikely to be influencedby prejudicial evidence which for one reason or another hadbeen admitted, especially when, as here, the judge cautionedhimself against himself being influenced by it.

In Siu Yuk-Shing,34 the accused was charged with being amember of the 14K triad society. Evidence was led that a triadaltar and other related triad articles were found in the accused’spremises. It was suggested to the prosecution witnesses thatthese were commonplace items and not indicative of triadactivities. In rebuttal, the prosecution was allowed to adduceevidence to prove that the accused had been convicted of being amember of the 14K triad society. He was convicted. The HongKong Court of Appeal held that evidence of the previousconviction was not admissible. On appeal, the Privy Councilaccepted that evidence of propensity was not generallyadmissible, but held that evidence which is logically probative ofthe offence charged is not rendered inadmissible merely becauseit discloses the commission of another offence. There, theknowledge of the accused as to the purpose of the articles wasrelevant. The Privy Council said:

It is not without significance that this was a trial by judgealone. If the judge had been sitting with a jury he would havehad to weigh carefully the probative value of such a previousconviction against the prejudice to the accused that wouldlikely to arise in the minds of the jury. The risk of suchprejudice overbearing the probative value of evidence is ofinfinitely less significance when a case is tried by a judge

34

alone. The judge must of course guard against any such resultbut his whole background and training have fitted him to doso. In a trial by a judge alone the exercise of excluding theevidence on grounds of prejudice becomes somewhat unrealwhen it is remembered that the judge must be informed of thenature of the evidence in order to rule upon whether or not it isadmissible. If the judge having ruled it inadmissible is to betrusted to put the evidence out of his mind he can surely betrusted to give it only its probative, rather than its prejudicial,weight if he rules that is admissible. The trial judge in thepresent case showed an entirely correct approach to this aspectof the case when he said:

[1996] 2 SLR 422.[1894] AC 57.[1975] AC 421.

[1994] 1 SLR 135 where the Court of Appeal held that by virtue of section30 of the Evidence Act, the confession of a co-accused implicating anaccused in the commission of the offence is, in joint trial for the sameoffence, admissible against the accused as substantive evidence, and not

The evidence of previous conviction will haveprejudicial effect but as I am sitting as both judge offact and of law I can see it will be minimal comparedwith its possible effect on a jury.

Recently, in Tan Meng Jee,35 the Court of Appeal had toconsider the principles applicable to the admission of similarfact evidence. The Court, having examined the leadingauthorities beginning with Makin36 and up to Boardman,37

including local decisions, rejected the categorisation approach ofMakin and approved the balancing test laid down in Boardman.A simpler approach would be for the court to deal with suchevidence on the basis of its reliability alone, ie, the weight to begiven to it, instead of reasoning along the traditional basis ofadmissibiliry and weight.

P. Confession of co-accused and the hearsay rule

The Court of Appeal’s decision in Chin Seow Noi38 continues tocause much concern to the criminal bar and to academic lawyers,

35363738

458 Singapore Law Review (1996)

notwithstanding the Court’s confidence in the professionalism oftrial judges in evaluating the probative value of the confession ofa co-accused implicating the accused. The decision was a bolddeparture from established authorities in admitting a special kindof hearsay evidence which, the Court declared, could besufficiently cogent, by itself, to convict the accused in anappropriate case. But to date, judicial caution has not permittedsuch a confession to be so used in a capital case. The reliabilityof such a confession must of course depend on its nature and thecircumstances in which it was made. If the co-accused hasvoluntarily confessed to a capital offence for which he has notbeen given immunity from prosecution, there should be noreason to doubt his statement implicating the accused, unlessthere is reason to believe that the statement was not true. Thereliability of such a confession can be also gauged by theconduct of the accused. Any risk of injustice can be reduced byrequiring the co-accused to make his defence first. If he testifies,he is subject to cross-examination by the accused. If he does not,there would be no reason why the accused should not testify, ifhe is innocent. No doubt his right to remain silent is affected, butno innocent accused should want to exercise this right in thecircumstances.

Any judge who is conscious and therefore concerned that ChinSeow Noi may easily result in a miscarriage of justice becausehis evaluation of the reliability of the confession of the co-accused may be faulty will no doubt decline to call for thedefence or to convict even if the accused keeps silent. But theway is open to him to require the presence of some othercorroborative evidence to support the co-accused’s confessionimplicating the accused. Such corroborative evidence need notbe of a degree that, in itself, is sufficient to convict the accused.That would be applying the previous law. But if the two, incombination and if unrebutted, would warrant the conviction of

merely as a piece of evidence to be taken into consideration with all theother evidence. The Court declined to follow a long line of authoritiesbased on the Privy Council decision in Bhuboni Sahu v Emperor AIR1949 PC 257.

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 459

the accused, then the defence may legitimately be called. Thecase of Ramachandran39 is relevant to this discussion.Ramachandran (“R”) and Krishnan (“K”) were convicted ofmurder committed with a common intention. The evidenceproved against R was as follows: R’s shoe imprint was found atthe scene of crime; four imitation precious stones which werepart of the 30 stones missing from the scene of crime wererecovered from him; the confession of K, the co-accused was asfollows:

I [Krishnan] admitted that Ramachandran and I committed themurder. I am the one who knocked the door. Both of us wentin, Ramachandran kicked the deceased and held both hishands. I then stabbed the deceased.

The Court of Appeal allowed the appeal of R on the ground thathe was convicted solely on the basis of K’s confession. This casewas decided just before Chin Seow Noi. The shoe imprint of Rand his possession of the stolen articles, when considered in thelight of K’s confession, were logically probative of hisengagement in an enterprise in which the victim was murdered.Chin Seow Noi would not have caused any injustice in this typeof case.

It is probably in the subject of hearsay evidence that thebiggest scope exists for the refinement of jury related principles.In Kearley,40 the police arrested the accused and found drugs inhis house but not in such quantities as to raise the irresistibleinference that the accused was a dealer. While the police weresearching the accused’s house, 11 telephone calls were made tothe accused’s home and answered by the police wherein thecallers were asking to be supplied with drugs. A majority of theHouse of Lords held that these 11 telephone calls wereinadmissible as hearsay and that the policeman who answeredthese calls were not allowed to give evidence of them. LordBrowne-Wilkinson dissented and took the view that the evidenceof the phone calls were firstly relevant, and secondly that the

39

40[1993] 2 SLR 671.

[1992] AC 228.

460 Singapore Law Review (1996)

The Australian courts have rejected Kearley. In Abrahamson,41

the South Australian Supreme Court held that evidence oftelephone calls making inquiries to purchase drugs areadmissible and relevant as tending to prove the existence of abusiness or activity of selling drugs, although it cannot be usedto prove the truth of any statements made by the callers. In thecontext of drug offences in Singapore, we are not troubled byKearley because the legislature has considered it more effectiveto deal with this kind of evidential problem by using rebuttablepresumptions of trafficking, but the specific problems arisingfrom the rules against all hearsay evidence remain in other areasof the law.

A non-jury trial does not demand that all the exclusionary rulesapplicable in a jury trial should be jettisoned. Judges are alsohuman beings and subject to the frailties of other human beings.But, they are less likely to be influenced by prejudicial evidenceand are able to consciously guard against it. What we need is tosubject every exclusionary rule to a critical analysis as to itspossible effects in a non-jury trial. For example, many accusedpersons who have been acquitted of sexual offences wouldcertainly have been convicted if their previous criminal records(antecedents) had been introduced in evidence. As a result, manyfactually guilty accused persons have been able to avoidpunishment because their antecedents were not made known tothe courts. This may be an area of law where the academics can

[1994] 63 SASR 139.

phone calls were not hearsay since they were used not to provethe truth of what was said but rather only to explain the caller’spurpose in making the calls. His Lordship noted at p 287 that:

... there may well be a good case for the legislature to reviewthe hearsay rule in criminal law. In cases such as the present ithampers effective prosecution by excluding evidence whichyour Lordships all agree is highly probative, and since itcomes from the unprompted actions of the callers, is verycreditworthy. ... A reform of the operation of the hearsay rulein criminal cases is long overdue.

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 461

41

devote their time and intellectual efforts in developing acoherent set of fair procedural and evidential rules appropriate tobench trials.

The time is ripe for us to take a fresh look at the criminalprocess in the light of what is appropriate to our circumstances.There is a case for arguing that the fundamental tenet of thecriminal justice system of Singapore should simply be that thefactually guilty accused should suffer punishment according tolaw and that therefore the criminal process should primarily bedirected to this end. The innocent accused will also have to besafeguarded, but the continuing use of exclusionary rules ofevidence is not necessarily the only or the best means to achievethis goal. What is perhaps more important is the integrity of thepeople who operate the system, ie, the investigative and theprosecutorial agencies, and the ultimate supervisor of thecriminal process, the judiciary. In other words, it is people whomake a system fair and just, and not the reverse.

PART II

A. A Fair Trial

In 1964, AL Goodhart wrote:

This idea of a fair trial has been the greatest contribution madeto civilisation by our Anglo-American polity.42

In our legal system, this idea is manifested in a form ofadversarial trial conducted before an independent and unbiasedtribunal according to procedural and evidential rules primarilydesigned to ensure as far as possible than an innocent accusedwill not be convicted. In Winston Brown, Steyn LJ (as he thenwas) said:

That everybody who comes before our courts is entitled to afair trial is axiomatic.43

“Fair Trial and Contempt of Court” (1964) 1 NYLJ 1.

[1995] 1 Crim App R 191, 198.

42

43

462 Singapore Law Review (1996)

Arad

In Haw Tua Tau,44 counsel for the appellant argued that theconcept of fair trial included the following features:

It is fundamental that a person charged with a criminal offenceshall have a fair trial. It is settled that that is best secured byadherence to certain basic rights and privileges which include(1) that a defendant shall be presumed innocent until provenguilty according to law; (2) that the burden of proving his guiltshall throughout be on the prosecution; (3) that the defendantshall be under no obligation to give evidence; and (4) that theevidence adduced must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Outside the trial itself, the criminal process has incorporatedmany procedural and evidential rules to ensure that onlyuntainted, direct and probative evidence obtained independentlyof the accused’s co-operation is admissible in evidence. Thus,section 121 of the Code allows a suspect or accused to refuse toanswer any question put to him by the police if it mayincriminate him, and hearsay evidence, however reliable, is notadmissible. The mere deprivation of any relevant evidence to theaccused by the prosecution may be treated as having denied theaccused a fair trial and the prosecution may be stayed.

In Haw Tua Tau, Lord Diplock also explained the scope ofsection 180 of the Code in terms of unfairness to the accused:

For reasons that are inherent in the adversarial character ofcriminal trials under the common law system, it does not placeupon the court a positive obligation to make up its mind at thatstage of the proceedings whether the evidence adduced by theprosecution has by then satisfied it beyond reasonable doubtthat the accused is guilty. Indeed it would run counter to theconcept of what is a fair trial under that system to require thecourt to do so.45

[1982] AC 136, 141

In State v Van den Berg [1995] 2 LRC 619, O’Linn J, in the context ofNamibia, said at page 631:

A perception exists in some circles that the fundamental right to a fairtrial focuses exclusively on the rights and privileges of accusedpersons. These rights, however, must be interpreted and given effect toin the context of the rights and interests of the law-abiding persons in

44

45

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 463

Arad

Arad

Arad

In contrast, it is rather unusual to find a judicial statement thatthe prosecution is also entitled to a fair trial, even though theelements of fairness to the prosecution may be difficult toidentify. In R v Derby Crown Court, Ex Parte Brooks, Sir RogerOmrod said:

The ultimate objective of this discretionary power (to stop aprosecution for abuse of process of the court) is to ensure thatthere should be a fair trial according to law, which involvesfairness to both the defendant and the prosecution.46

[Emphasis added.]

If, as Lord Diplock says, the making of premature findings offact against an accused is unfair to the accused, the making ofpremature findings of fact against the prosecution must equallybe unfair to the prosecution. Any rule or practice which permitsthe court to do this is equally unfair. The trial is accepted as acivilised means of determining the guilt or otherwise of theaccused. Premature findings of facts leading to an acquittal willshut out the prosecution’s case unjustifiably.47

In any prosecution, the integrity of the criminal process itself ison trial as much as the accused is on trial. Prosecutors do notprosecute any person for any offence unless there is sufficientevidence to show that he has committed that offence.Accordingly, assuming the integrity of the process, a trialprocedure which allows the judge to acquit summarily an

society and particularly the persons who are victims of crime, many ofwhom may be unable to protect themselves or their interests becausethey are dead or otherwise incapacitated in the course of crimescommitted against them.

(1984) 80 CR APP R 164, 168-169.

Lord Parker’s Practice Note [1962] 1 All ER 448 supports the idea of afair trial for the prosecution. The Note reads:

Those of us who sit in the Divisional Court have the distinctimpression that justices today are being persuaded all too often touphold a submission of no case. In the result, this court has had onmany occasions to send the case back to the justices for the hearing tobe continued with inevitable delay and increased expenditure.

46

47

464 Singapore Law Review (1996)

Arad

Arad

accused person, especially on a serious charge, on a prematureevaluation of the evidence, is not in the public interest.

B. Haw Tua Tau—The continuing debate

It is in the context of a fair trial to the prosecution that one canappreciate the divergence between Singapore law and Malaysianlaw on the test which a court should apply in deciding whether acase is made out against the accused at the intermediate stage ofthe trial, ie, at the end of the prosecution’s case. Haw Tua Tauhas decided that the prima facie test is applicable. The courts inSingapore and in Brunei have accepted Haw Tua Tau. TheMalaysian courts initially accepted Haw Tua Tau, but changeddirection in Khoo Hi Chiang48 when the Supreme Court decidedthat the defence should not be called unless, at the end of itscase, the prosecution had proved its case beyond a reasonabledoubt. This test is referred to as the maximum evaluation test incontrast to the prima facie test which is called the minimumevaluation test. The Court of Appeal declined to follow Khoo HiChiang, but in Arulpragasan49 the Federal Court (by a majorityof 4:3) held in favour of the maximum evaluation test.

As the law in Singapore is settled, it may be thought pointlessto discuss the subject further. However, there is some merit indoing so, if only because the Malaysian approach is seen bymany as giving greater protection, and therefore fairer to theaccused. The Malaysian approach is not bereft of judicial andacademic support, for somewhat different reasons. Academicopinion in Singapore appears to supports it,50 which prima faciemay reinforce its soundness in law. However, it is my thesis thatthe Singapore approach is not only correct in law (ie, as a matterof statutory interpretation) but also upholds the principle that an

[1994] 1 MLJ 265.

SC Cr A No 05-237-92.

See Tan Yock Lin, Criminal Procedure (1996 Ed) where the authorcomments at p 705 that “the reasons for [Khoo Hi Chiang] rejecting HawTua Tau’s case are sound” and also Michael Hor, “The Privilege AgainstSelf-Incrimination and Fairness to the Accused” [1993] SJLS 35.

48

49

50

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 465

innocent person accused of an offence (“innocent accused”)should not be subject to a higher risk of conviction than a guiltyaccused. It is consistent with the idea of a fair trial for theaccused as well as for the prosecution and it rests on a strongerfoundation than what is apparent in Lord Diplock’s reasoning inHaw Tua Tau. What follows is an outline of a conceptual and astatutory analysis in support of the prima facie test.

In Haw Tua Tau, Lord Diplock referred to the analogy of a jurytrial to show the separate functions of law finding and factfinding in an adversarial trial conducted before a judge who isvested with both functions. He said:

466 Singapore Law Review (1996)

... the same principle [as in a jury trial] applies to criminaltrials where the combined roles of decider of law and deciderof fact are vested in a single judge (or in two judges tryingcapital cases). At the conclusion of the prosecution’s case whathas to be decided remains a question of law only. As deciderof law, the judge must consider whether there is someevidence (not inherently incredible) which, if he were toaccept it as accurate, would establish each essential element inthe alleged offence. If such evidence as respects any of thoseessential elements is lacking, then, and then only, is hejustified in finding “that no case against the accused has beenmade out which if unrebutted would warrant his conviction,”within the meaning of section 188(1). Where he has not sofound, he must call upon the accused to enter upon hisdefence, and as decider of fact must keep an open mind as tothe accuracy of any of the prosecution’s witnesses until thedefence has tendered such evidence, if any, by the accused orother witnesses as it may want to call and counsel on bothsides have addressed to the judge such arguments andcomments on the evidence as they may wish to advance.

The Singapore courts and the Malaysian courts disagree on theinterpretation of the corresponding provisions, and in particular,the effect of the words “if unrebutted would warrant aconviction”. Haw Tua Tau says that these words mean that if thedefence fails to adduce any rebuttable evidence, it could lead tohis conviction. Khoo Hi Chiang and Arulpragasan say that thesewords demand a conviction. However, the disagreement oninterpretation can be disregarded for the purpose of the present

Arad

Arad

that it is highly “artificial” for the judge in a bench trial, tosuspend judgment on the evidence (where he cannot believeit), to call for the defence on the assumption that theevidence is true; and then not to believe it if the accusedkeeps silent (where the judge decides that it is unsafe toconvict);

that Haw Tua Tau forbids the judge in a bench trial at theintermediate stage of the trial to determine whether theprosecution witnesses are telling the truth; this is contrary tothe law as stated in Archbold;51

that the maximum evaluation test is not unfair to theaccused, but the prima facie test is unfair to the accusedbecause it allows the prosecution to repair any deficienciesin its case and to subject the accused to self-incriminationthrough cross-examination; the greater the burden on theprosecution to establish a case, the greater the protectionoffered to the accused;

Archbold’s Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice (1993 Ed) at 4-307.The relevant passage in Archbold’s reads:

In their summary jurisdiction magistrates are judges both of facts andlaw. It is therefore submitted that even where at the close of theprosecution case, or later, there is some evidence which, if accepted,would entitle a reasonable tribunal to convict, they nevertheless havethe same right as a jury to acquit if they do not accept the evidence,whether because it is conflicting, or has been contradicted or for anyother reason. It is submitted that the practice note reported in [1962] 1ALL E.R. 448 must be read in this light. In any event, there appears tobe no authority as to the issue of practice directions in criminal mattersrelating to questions of law as opposed to practice.

17 Sing LR 10th Singapore Law Review Lecture 467discussion, even though it is this that is the ostensible reason forthe divergence. What is relevant is which result is moreacceptable to the criminal process. In Arulpragasan, thefollowing points have been made in relation to bench trials ascontrasted with jury trials:

(a)

(b)

(c)

51

It is arguable that any incongruity in a judge having to performmental gymnastics in applying the prima facie test to a casewhich results in an acquittal if the accused keeps silent appliesequally in a case where the maximum evaluation test is appliedand the judge, after hearing the defence, backtracks and decidesthat the case has not been proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Sothis is not a valid argument in favour of one or other of the twotests. Indeed, it is arguable that the prima facie test is simpler toapply because it merely requires the judge to suspend hisjudgment on the evidence (which judges often do with respect toother factual issues) whereas the maximum evaluation test mayrequire the judge to make two opposite judgments at differenttimes on the same facts.

The second point misunderstands the judgment of LordDiplock in Haw Tua Tau. He did not decide that the judge mustnot perform any evaluation exercise in all cases. At page 150, hesaid:

Section 214(i) reads: “When the case for the prosecution is concluded theCourt, if it considers that there is no evidence that the accused committedthe offence, shall direct the jury to return a verdict of not guilty.”

Section 190 reads: “When the case for the prosecution is concluded theCourt, if it finds that no case against the accused had been made out whichif unrebutted would warrant his conviction shall record an order ofacquittal, or, if it does not so find, shall call on the accused to enter on hisdefence.”

52

53

For reasons that are inherent in the adversarial character ofcriminal trials under the common law system, it does not placeupon the a positive obligation to make up its mind at that stageof the proceedings whether the evidence adduced by theprosecution has by then already satisfied it beyond reasonabledoubt that the accused is guilty ... [Emphasis added.]

Similarly at page 155, Lord Diplock also said:

(d) that jury trials in Malaysia are regulated under a provision,viz, section 214(i)52 of the Code (M) which is differentlyworded from section 19053 applicable to bench trials,indicating that legislature has provided different tests forjury trials and summary trials.

468 Singapore Law Review (1996)

Lord Diplock was not unfamiliar with bench trials. Summarytrials before magistrates have existed for a long time in England.But, he insisted that the judge in a bench trial must consciouslyseparate his dual functions because the issue whether the defenceshould be called is a question of law, and to answer a question oflaw, you must assume the facts so long as there is some evidenceon which those facts can be justified.54 In Yeo Tse Soon,55 theCourt of Appeal of Brunei accepted that the principle that issuesof fact should not be decided (even provisionally) until thewhole of the evidence in the case has been heard is fundamentalto the adversarial procedure. The Court suggested that seriousconsequences would follow if the principle is abandoned, evenin a bench trial.

The principle that the judge should not perform his dualfunctions at the same time at the intermediate stage of the trialmakes good practical sense. The question of usurping thefunction of the jury does not arise, that being logicallyimpossible in a bench trial. The crucial question is whether it isfair for him to make a finding of fact at that stage. The answer isgenerally “No”, because it would have to be based on, inter alia,his impressions on the credibility of the witnesses. A judge maynot find the prosecution’s witnesses convincing at that stage ofthe process, but that does not mean that the witnesses are nottelling the truth. What the judge believes as not credible mayturn out to be true, in the light of other evidence. This accordswith human experienced.56 The point is not that he should find on

Lord Diplock did not refer to the standard of proof in his judgment,because it was not necessary to. But it can be conceded that if the judgehad to find the facts at that intermediate stage, the standard of proof wouldnecessarily have been beyond a reasonable doubt.

[1994] 2 LRC 610.As was said by Hamlet (Hamlet Act 1, Scene 5, 166-7):

54

5556