IN TODAY’S PRESS: $206 IN SAVINGS (exact amount may vary, depending on delivery area) THANKSGIVING WISHES BEGIN, B1 Bite-size updates on our Twitter feed at twitter.com/grpress INDEX Advice/Puzzles .........I4-5 Automotive Ads .......... D1 Business ........................F1 Deaths ......................... B6 Entertainment ..............E1 Jobs .............................. F5 Lottery.......................... A2 Opinions............... A20-21 Real Estate Ads........ H&G Region.......................... B1 Sports ........................... C1 Weather ..................... B10 1 2 3 4 5 Michigan voters are asked every 16 years to vote on a ballot proposition to convene a constitutional convention. The question will be on the November ballot. If voters say yes, according to legislation proposed by Secretary of State Terri Lynn Land, partisan primaries for 148 delegate seats, one from each House and Senate district, would be Feb. 22, 2011. Primary winners would square off May 3. The constitution says delegates would convene in Lansing no later than Oct. 4, but Land's bill would require them to meet at noon July 12. The next secretary of state would preside until delegates select a convention president. Delegates then deliberate the constitution. The proceedings would be covered by Michigan lobbying law, meaning only registered lobbyists could seek to influence the proceedings. Any changes must be agreed upon by a majority of the delegates. The proposed constitution or amendments must be submitted to voters not less than 90 days after the convention adjourns. Voters decide on a new constitution or amendments by a simple majority vote. BY PETER LUKE LANSING BUREAU L ANSING — The Michigan Constitution, 1963 version, was the product of seven months of deliberation at a convention called by voters persuaded that a half-century of seismic economic, social and political change had rendered obsolete the old one crafted in a long-gone agrarian era. If voters had doubts about the new one — it was ratified by a 7,424-vote margin of 1.6 million cast — they apparently forgot what they were. In 1978 and 1994, voters rejected the idea of another constitutional convention by a combined 2.7 million votes. Voters will be asked again on Nov. 2. Proposal 1 is the result of a constitutional requirement that automatically asks voters every 16 years whether to set in motion the process for overhauling Michigan’s organizing framework for state and local government. If voters again reject the idea, nothing happens and they will be asked to consider the question again in 2026. If they say “yes,” however, the process for assembling 148 delegates, one from each legislative district, for a “con-con” in Lansing would begin. Those delegates would be elected in partisan primaries on Feb. 22, 2011. The final two candidates would square off May 3. The convention would begin no later than Oct. 4, although legislation recommended by Secretary SEE CON-CON, A12 www.mlive.com $2.00 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2010 To our readers: The 10th and final installment in our monthly series on Michigan issues examines the question of rewriting the constitution, which voters will decide Nov. 2. We explain the process and explore its pros and cons. — Paul M. Keep, editor BACK TO SQUARE ONE? MICHIGAN VOTERS FACE A DECISION ABOUT THE STATE CONSTITUTION SO YOU WANT TO HOLD A CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE PRESS ILLUSTRATION/MILT KLINGENSMITH GREEN DAY: MICHIGAN STATE GIVES U-M FANS THE BLUES, C1 “I already voted yes absentee because the state has changed over the last decade or two. I want the process to be kept out of the hands of the politicians and put together with regular people smart enough to see the long-term needs of the state. They can take a look at things such as education and the need for more charter schools, a voucher system and taxes. If you want jobs, you have to send a signal you’re serious about recruiting.” — retired financial consultant Ray Vander Weele, 73, of Grand Rapids JOIN THE CONVERSATION: MLIVE.COM/MI10 WHAT READERS ARE SAYING ABOUT CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION MORE INSIDE Michigan’s constitution dates to 1963 — but it has been amended 31 times. A look at those changes (and 37 failed amendments) on page A12 Neither candidate for governor supports Proposal 1. Their campaigns explain why. A12 Looking back at the 1961-62 convention: George Romney established political credentials; women participated for the first time. A13 ©2010, The Grand Rapids Press 3881142-01

1010-Mi10-Constitution

Mar 24, 2016

IN TODAY’S PRESS: $206 IN SAVINGS JOIN THE CONVERSATION: MLIVE.COM/MI10 www.mlive.com To our readers: The 10th and final installment in our monthly series on Michigan issues examines the question of rewriting the constitution, which voters will decide Nov. 2. We explain the process and explore its pros and cons. — Paul M. Keep, editor Bite-size updates on our Twitter feed at twitter.com/grpress Voters decide on a new constitution or amendments by a simple majority vote. BY PETER LUKE

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

IN TODAY’S PRESS: $206 IN SAVINGS(exact amount may vary, depending on delivery area)

THANKSGIVING WISHES BEGIN, B1

Bite-size updates on our Twitter feed at twitter.com/grpress

INDEXAdvice/Puzzles .........I4-5Automotive Ads ..........D1Business ........................F1Deaths ......................... B6

Entertainment ..............E1Jobs .............................. F5Lottery..........................A2Opinions ............... A20-21

Real Estate Ads ........ H&GRegion .......................... B1Sports ........................... C1Weather .....................B10

1 2

3

45

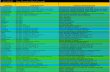

Michigan voters are asked every 16 years to vote on a ballot proposition to convene a constitutional convention. The question will be on the November ballot.

If voters say yes, according to legislation proposed by Secretary of State Terri Lynn Land, partisan primaries for 148 delegate seats, one from each House and Senate district, would be Feb. 22, 2011. Primary winners would square off May 3. The constitution says delegates would convene in Lansing no later than Oct. 4, but Land's bill would require them to meet at noon July 12. The next secretary of state would preside until delegates select a convention president.

Delegates then deliberate the constitution. The proceedings would be covered by Michigan lobbying law, meaning only registered lobbyists could seek to influence the proceedings. Any changes must be agreed upon by a majority of the delegates.

The proposed constitution or amendments must be submitted to voters not less than 90 days after the convention adjourns.

Voters decide on a new constitution or amendments by a simple majority vote.

BY PETER LUKE

LANSING BUREAU

LANSING — The Michigan Constitution, 1963 version, was

the product of seven months of deliberation at a convention called by voters persuaded that a half-century of seismic economic, social and political change had rendered obsolete the old one crafted in a long-gone agrarian era.

If voters had doubts about the new one — it was ratifi ed by a 7,424-vote margin of 1.6 million cast — they apparently forgot what they were. In 1978 and 1994, voters rejected the idea of another constitutional convention by a combined 2.7 million votes.

Voters will be asked again on Nov. 2.

Proposal 1 is the result of a constitutional requirement that automatically asks voters every 16 years whether to set in motion the process for overhauling Michigan’s organizing framework for state and local government.

If voters again reject the idea, nothing happens and they will be asked to consider the question again in 2026.

If they say “yes,” however, the process for assembling 148 delegates, one from each legislative district, for a “con-con” in Lansing would begin.

Those delegates would be elected in partisan primaries on Feb. 22, 2011. The fi nal two candidates would square off May 3. The convention would begin no later than Oct. 4, although legislation recommended by Secretary

SEE CON-CON, A12

www.mlive.com $2.00SUNDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2010

To our readers: The 10th and final installment in our monthly series on Michigan issues examines the question of rewriting the constitution, which voters will decide Nov. 2. We explain the process and explore its pros and cons. — Paul M. Keep, editor

BACK TO SQUARE ONE?MICHIGAN VOTERS FACE A DECISION ABOUT THE STATE CONSTITUTION

SO YOU WANT TO HOLD A CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE

PRESS ILLUSTRATION/MILT KLINGENSMITH

GREEN DAY: MICHIGAN STATE GIVES U-M FANS THE BLUES, C1

“I already voted yes absentee because the state has changed over the last decade or two. I want the process to be kept out of the hands of the politicians and put together with regular people smart enough to see the long-term needs of the state. They can take a look at things such as education and the need for more charter schools, a voucher system and taxes. If you want jobs, you have to send a signal you’re serious about recruiting.”

— retired financial consultant Ray Vander Weele,73, of Grand Rapids

JOIN THE CONVERSATION: MLIVE.COM/MI10

WHAT READERS ARE SAYING ABOUT CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION MORE INSIDE

Michigan’s constitution dates to 1963 — but it has �been amended 31 times. A look at those changes (and 37 failed amendments) on page A12

Neither candidate for governor supports�Proposal 1. Their campaigns explain why. A12

Looking back at the 1961-62 convention: George �Romney established political credentials; women participated for the first time. A13

©2010, The Grand Rapids Press

����� ��� ���� �� ����� ���� � �������

3881142-01

A12 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2010 THE GRAND RAPIDS PRESS

CONTINUED FROM A1

of State Terri Lynn Land would have the delegates assemble three months earlier.

There is no deadline, and the con-con could adjourn without making any changes at all. If a new constitu-tion were written, voters would be asked to ratify it no earlier than 90 days after delegates approved it.

Critics from across the partisan spectrum say a convention would paralyze the state for months, if not years, as a new governor and Legis-lature continue the struggle to keep the state’s fi nances in balance and re-spond to Michigan’s ongoing econom-ic trouble. Michigan’s 2010 candidates for governor, Republican Rick Snyder and Democrat Virg Bernero, oppose holding a constitutional convention.

Proponents say the Michigan Con-stitution has been rewritten every half-century or so dating back to 1850, and that the conditions warranting the last convention — a dysfunctional state government no longer able to effectively deliver services with the resources available — are holding Michigan back again.

No major campaignVoters shouldn’t expect to hear

those arguments played out in state-wide 30-second TV ads.

Opponents have a website,nomichiganconcon.com, but, as of their last campaign fi nance fi ling, had just $45,000 in the bank.

Proponents, including the group behind website yesonproposal1.com, don’t appear to have any money at all. But their argument was elevat-ed by Sen. Tom George, who made the necessity of a convention a key plank in his unsuccessful Republican campaign for governor. Gov. Jennifer Granholm supports a convention as well, although she is not leading a campaign for voter approval.

Tim Kelly, chairman of the Saginaw County Republican Party, has joined with George in pushing for a conven-tion. He argued that status quo forces in both parties are resistant to the scale of change that only a convention could deliver.

“Michigan is as broken as a state can be, and piecemeal legislation and tinkering around the edges isn’t going to get us to where we need to go,” he says. “We need big change rapidly.”

What kind of change?One of the drivers of a convention

is the fact that twice in the past three years, state budgets haven’t been com-pleted by the Oct. 1 start of the new fi scal year. And when completed, the budgets are soon back out of balance as expected revenues fail to fund the appropriated spending.

Former Grand Rapids Mayor John Logie said a convention could move the fi scal year back to July 1, dock legislative pay if the budget is late and allow lawmakers in a part-time Legislature to serve more time in of-fi ce, 14 years, than current term limits provide. Lawmakers and local offi -cials could be given more fl exibility in considering revenue options, among them a graduated income tax now constitutionally prohibited and a sales tax option for local governments.

Opponents, led by the Michigan Chamber of Commerce and other groups, say a convention simply isn’t needed. They say while Michigan is ailing, the cause of those ailments won’t be found in the constitution.

They also cite an estimated$45 million cost for a convention. Lo-gie said that would be over two years and could be made up in one year if a convention eliminated one chamber of the Legislature.

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Midland and the Michigan Education Association don’t agree on much, but both say Proposal 1 should be defeated.

“(Michigan’s) problems aren’t caused by the constitution, nor can they be fi xed by it,” said Jack McHugh, a legislative analyst for the Mackinac Center. “The desire to rearrange the institutional furniture is a cry of frus-tration, not a plausible means of fi xing the underlying problems. ”

The MEA’s Doug Pratt said a con-vention that “would tear up the docu-ment and start over is overkill. The basic structure of our constitution is fi ne.”

But it isn’t carved in stone.

Plenty of amendmentsIf voters and the state’s political

leadership have generally opposed calling another convention, they have not been shy about amending it, or trying to do so anyway.

Of the 68 amendments proposed since 1966, 31 were approved and 37 rejected. Forty-two were placed on the ballot through the required two-thirds vote of the Legislature, with half approved and half rejected by

voters. Of the 26 amendment propos-als placed on the ballot through citi-zen petition drive, 10 were approved and 16 rejected.

If there were a convention next year, delegates would have to decide how to tackle issues voters have already decided in the polling booth since the last convention was ratifi ed.

Amendments approved or rejected over the past four decades involved core issues of state government, had direct impact on citizen pocketbooks and changed the social landscape.

In 1992, voters approved some of the strictest term limits in the nation for the Michigan Legislature. After six years in the House and eight in the Senate, offi ceholders are booted out. There is growing consensus among interest groups that term limits have decimated the Legislature’s capacity to govern. That consensus, say term-limit supporters, evaporates outside Lansing.

After years of growing frustration with inequities in K-12 funding and rising property tax bills, voters in 1994 approved Proposal A. The whole process consumed the Capitol for a period longer than the last constitu-tional convention. The end product traded most residential property taxes for school purposes for a 50 percent increase in the sales tax. It capped an-nual increases in property tax at infl a-tion and sought, with some success, to

equalize per-pupil spending. In 2004, voters were asked to take

on another hot-button issue when they defined marriage as between “one man and one woman.” Two years later, they banned the use of affi rma-tive action in university admissions and government hiring. And in 2008, they endorsed an amendment that overturned a statutory ban on embry-onic stem cell research.

Fiscal progressives at a convention would likely seek to change Michi-gan’s fl at rate income tax to a gradu-ated system that would apply different rates to different levels of income. Voters three times — in 1968, 1972 and 1976 — rejected that approach. The Headlee Amendment of 1978 limits state tax collections to 9.49 percent of total Michigan personal income. Since Michigan is collecting about 7 percent now, fi scal conservatives

might seek to put a new, lower cap in place.

Then there are constitutional is-sues voters have never been asked to address.

There could be demands for a death penalty, which Michigan banned in 1846. A possible fight over abor-tion might seek to constitutionally prohibit it, should Roe v. Wade be overturned.

Michigan’s constitution prescribes an annual start date for the Legisla-ture — the fi rst Wednesday in January — but not an end date. That’s left to the House and Senate, which typi-cally adjourn the week after Christ-mas. Most states have a part-time Legislature with part-time pay and a con-con could make that change here. Nebraska is the only state with a unicameral Legislature; Michigan could be the second.

Michigan’s last constitution de-clined to tackle the issue of how many local units of government the state should have. Since 1963, the number of units has actually grown, from 1,851 to 1,858. Nearly 60 percent of units have populations of less than 2,500.

In the realm of elections, a conven-tion could transfer authority to redraw legislative and congressional districts from the Legislature to a nonpartisan independent commission, as is done in Iowa.

Judges at every level are elected in nonpartisan primaries, except at the Michigan Supreme Court, where jus-tices are nominated at partisan con-ventions. Convention proponents like Logie said, given the millions spent on high court elections, justices should be appointed by the governor after being recommended .

In the area of education, a conven-tion battle could be fought on the issue of local control. Local school boards still manage labor contracts, school calendar and K-8 curriculum. But Proposal A transformed how K-12 schools are funded, with the bulk of revenue for education distributed from Lansing. There would be pres-sure to consolidate at least the busi-ness management of districts along county lines. Education advocates at a convention could push for consti-tutional language that says the state funding for schools also be uniform and adequate.

More political gridlock?Critics of a convention say the po-

litical ingredients that lead to dead-lock in the Capitol could produce the same result for a convention.

Special interest cash that funds much of Michigan politics would in-fl uence the outcome of delegate elec-tions, producing winners beholden to the groups that helped fi nance their selection. Many delegates could well be former legislators with long-stand-ing relationships with lobbyists who arguably have a lot more clout than they did a half-century ago.

“The same careerist political class who created the mess and benefi t from it will be (convention) delegates,” said the Mackinac Center’s McHugh.

Logie said the fact that dozens of interest groups representing business and labor oppose a constitutional con-vention provide a clear signal as to why one is needed: It’s the “vested interests trying to keep the same old system.”

Contact Peter Luke at 517-487-8888or e-mail him at

1966: Lowering the minimum voting age from 21 to 18. Put on the ballot by the Legislature, a proposed amendment to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 was the first attempt to amend the new constitution. It was defeated 64-36 percent.

1968: When the Michigan Legislature adopted a flat rate income tax authorized by the new constitution the preceding year, lawmakers put on the 1968 ballot an amendment to reverse the constitution’s ban on a graduated income tax rate. Those with lower incomes would pay lower rates, and those with higher incomes would pay higher rates. It was rejected 77-23 percent.

1970: The first amendment placed on the ballot through petition drive banned the use of public tax dollars for direct aid to parochial and other non-public schools or their students. It was approved 57-43 percent.

1970: A second attempt to lower the voting age from 21 to 18 went down, 61-39 percent. The U.S. Supreme Court required the change in 1971.

1972: The Michigan Lottery is born. Voters authorized the Legislature to create a lottery and sell lottery tickets by a 73-27 percent margin.

1972: In the same May special election, voters rejected, 51-49 percent, a measure that would have allowed lawmakers to be appointed to another post while still in their elected office.

1972: The first of what would be several attempts to cut property taxes funding schools and local governments was rejected 58-42 percent.

1972: A second attempt, this one through petition drive, to allow for a graduated income tax was rejected 69-31 percent.

1974: An amendment exempting groceries and precription drugs from the sales tax was approved 56-44 percent.

1976: Voters rejected, 57-43 percent, an amendment that would have limited state tax collections to 8.3 percent of total Michigan personal income.

1976: The third and final attempt to authorize a graduated income tax went down, 72-28 percent.

1978: In their first chance to call for a new constitutional convention in 16 years , voters took a pass, 77-23 percent. Vote total — 2,112,549 nay, 640,286 yea.

1978: After the drinking age was lowered to 18 by the Legislature in 1971, voters approved, 57-43 percent, an amendment prohibiting alcoholic beverages from being sold to, or possessed by, persons under the age of 21.

1978: Voters approved, 52-48 percent, the Headlee Amendment, which capped the growth of property taxes and the collection of state taxes at 9.49 percent of Michigan personal income.

1978: Voters rejected, 74-26 percent, the first of two attempts to overturn the 1970 vote on aid to private schools through the creation of a voucher system.

1980: Two years after voters raised the drinking age to 21, lawmakers put an alternative on the ballot to lower it to 19. Voters, 64-36 percent, didn’t say “cheers!”

1980: Voters had the choice of two property tax cut plans: one put on the ballot by petition, the other by the Legislature. They said “no” to both.

1980: Asked to fix an omission in the state constitution that provides no means of replacing a lieutenant governor who resigns or dies in office, voters said don’t bother, 58-42 percent.

1982: Determining that ballots are long enough as it is, voters opposed, 63-37 percent, making seats on the Michigan Public Service Commission elected positions.

1984: Voters established, 65-35 percent, the Natural Resource Trust Fund, which collects oil and natural gas royalties for the purchase of public open space and recreational lands.

1988: By 80-20 percent, voters put victims rights in the constitution, including the right to timely court disposition and to make a statement at sentencing.

1992: Term limits for governor, secretary of state, attorney general (eight years total) and the Legislature (six years total House and eight years total Senate) were approved by voters, 59-41 percent.

1994: Voters approved Proposal A, 61-39 percent, which eliminated all but 6 mills of property tax for school operations, raised the sales tax from 4 percent to6 percent and capped annual property tax increases to inflation.

1994: Asked for the second time whether to call a constitutional convention, voters again pointed thumbs down, 72-28 percent. Vote total — 2,008,070 nea, 777,779 yea.

1996: To be elected or appointed, judges in Michigan have to be practicing lawyers for at least five years, voters agreed 82-18 percent.

2000: For the second time, voters rejected, 69-31 percent, a measure that would have provided taxpayer-funded vouchers for private school education.

2000: A measure advanced by local governments to require a two-thirds vote of the Legislature on any measure impacting cities, counties and townships was rejected by voters, 67-33 percent.

2004: Voters adopted, 59-41 percent, a state constitutional barrier against gay marriage, civil unions and domestic partner benefits.

2004: Voters agreed, 58-42 percent, with the three Detroit casino owners, which funded the petition drive, that any additional commercial (non-Native American) casinos in Michigan must have voter approval.

2006: As a response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that the University of Michigan could consider race as a factor in its law school admissions, voters, 58-42 percent, barred any use of affirmative action in university admissions or governmental hiring or contracting.

2008: By 53-47 percent, voters put in place constitutional protections for embryonic stem cell research.

SOME CHANGES TAKE PLACE AT THE BALLOT BOX

HOW WE GOT HEREA REVIEW OF AMENDMENTS THAT PASSED AND FAILED

Voters have twice rejected calling a new constitutional convention, but they amended the document 31 times, and rejected 37 other attempts.

PRESS PHOTO

Through the years: An editorial cartoon that appeared in the Press and other papers suggests voting rights were not up for discussion at the 1962 constitutional convention. Ballot initiatives to reduce the age failed in 1966 and 1970, before a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1971 set the national voting age at 18.

— Compiled by Peter Luke

CON-CONQUESTION IS ONNOV. 2 BALLOT

FOR EXAMPLE

RICK SNYDER, REPUBLICAN

Bill Nowling, campaign spokesman:“Rick thinks the democratic process would be hijacked from the people by special interests trying to influence the process.It would also delay doing things we need to get done by at least 18 months, and Michigan just can’t afford to wait that long. ”

VIRG BERNERO, DEMOCRAT

Cullen Schwartz, campaign spokeman:“Virg is opposed to throwing out the state’s constitution and focusing state leaders’ attention on writing a new one. The focus should remain exclusively on getting Michigan’s economy back on track and getting people back to work.”

How governor candidates stand on Proposal 1

CONNECT Opposed:�

nomichiganconcon.com

In favor�yesonproposal1.com

THE GRAND RAPIDS PRESS SUNDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2010 A13

THE GRAND RAPIDS PRESS

George Romney was labeled the one to watch as Michigan’s last con-stitutional convention took shape in October 1961. The words proved prophetic.

The Oakland County Republican and president of American Motors Corp. was widely rumored to have political ambitions. A high-profi le role in writing a new constitution couldn’t hurt.

“Romney, at 54, is one of the few delegates who look like a governor, a U.S. Senator or President of the Unit-ed States,” wrote William Kulsea, who headed the Lansing bureau then for The Grand Rapids Press and other Booth newspapers.

Romney was a leading candidate for the con-con presidency, a job that went to Stephen S. Nisbet of Fremont. Accounts of the balloting process sug-gested Romney was cagey in his run for the top convention job.

“Romney talked, fuzzily to some and semantically to others, about the GOP caucus choosing a ‘preferred’ candidate who could be formally cho-sen by the entire convention of 144 men and women, and not by the 99 GOP delegates alone.”

His promise — to assure a biparti-san approach to rewriting the state’s governing document — was not enough to win the presidency.

In the end, Romney became a convention vice president, serving alongside another Republican, Ed-ward Hutchinson, of Fennville, and Democrat Tom Downs of Detroit.

“This ‘troika’ is to be driven by Nis-bet, the president, but all eyes are on Romney and Hutchinson,” wrote Kulsea.

Kulsea observed that some cheered Romney while others jeered him but “all have some respect for him” and that he “gave off sparks” as a delegate.

Those sparks indeed translated to political cachet.

Buoyed with the name recognition and political acumen he gained during the convention, Romney went on to win the governor’s race in November, 1962. He was elected twice more (the 1963 constitution changed governor’s terms from two years to four begin-ning with the 1966 election) and ran for president in 1968.

He was a leading contender for the GOP nomination, but a gaffe — he backed off his earlier support for the Vietnam War and said he was “brainwashed” by military offi cials — doomed his campaign.

President Richard Nixon later ap-pointed him secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

While many of the 1961-62 con-con issues would be resurrected in a 2011 convention, much has changed in politics.

As late as April 1962, Romney was only “a rumored candidate for gover-nor.” Candidates to be the state’s top executive in 2010 were raising funds in 2008, and some were fi rmly in by early 2009.

Romney’s son, Mitt, a former gov-ernor of Massachussetts, was a GOP candidate for president in 2008 and is gearing up for another run in 2012.

— Compiled by Jeff Cranson

BY MONICA SCOTT

THE GRAND RAPIDS PRESS

GRAND RAPIDS — Only six years before Philip Morris suggested to the world that smoking their new ciga-rettes, Virginia Slims, would mark a woman as arrived and liberated, Mich-igan for the fi rst time allowed them a hand in drafting a constitution.

Eleven women were among the 144 elected delegates at Michigan’s 1961-62 constitutional convention. Because women in Michigan did not gain full suffrage rights until 1919, women were not allowed to participate in previous constitutional conventions.

Among the fi rst female delegates to the convention that resulted in the 1963 constitution were Grand Rapids natives, Republicans Ella Koeze and Dorothy Judd. The Michigan delegates were broken into 13 committees. Judd served on the committee on public information and Koeze, the commit-tee on legislative powers.

“There were more opportunities for women to break through entrenched power structures in conventions than in Legislatures,” said John Dinan, a political science professor at Wake Forest University. “State electorates proceeded on this with different lev-els of progressiveness, with some se-lecting women and minority delegates earlier than others.”

Along with the 11 women, 13 black delegates participated in that 1961-62 convention for the fi rst time, said Su-san Fino, a political science professor at Wayne State University.

Their involvement led to the equal protection provision of the Declara-tion of Rights and the creation of the Civil Rights Commission, she said.

“The delegates were very con-cerned about the rights of African-Americans,” Fino said. “Equal rights for women did not fare so well. Ad-ditionally, a provision against gender discrimination failed.”

Still, Dinan said, particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s, when

conventions were held in great num-bers around the country, the process often was more inclusive of women.

The state’s women made their presence felt in a number of areas to address what they called an “unman-ageable constitution,” especially those related to education and welfare .

“The conventions opened up op-portunities for a whole range of other voices on issues,” said Robert Wil-liams, associate director of the Cen-ter for State Constitutional Studies at Rutgers University.

“A lot of women in those days had gained a good deal of experience in the League of Women Voters,” Wil-liams said. “Voters and business wom-en clubs. They were sophisticated and well-educated.”

Running for delegate, Williams said, often doesn’t require the same type of party backing as a regular election. He said the idea of having a one-time impact on the structure of the laws ap-pealed to a lot of women of the era.

E-mail: [email protected]

BY MONICA SCOTT

THE GRAND RAPIDS PRESS

G RAND RAPIDS — Consti-tutional conventions are rare. Voters in eight states have already rejected ref-erendums this decade

and state constitution scholars aren’t predicting Michigan will be the exception.

“It’s a very negative time for government,” said Robert Wil-liams, associate director of the Center for State Constitutional Studies at Rutgers University. “People are afraid of losing out to the politicians and other vested in-terests, and that’s why very few ref-erendums get approved anymore.”

Fourteen states require manda-tory convention referendums in intervals of nine, 10, 16 (Michigan) or 20 years. Voters in Illinois, Con-necticut and Hawaii were the last to reject the idea, in 2008. Sixty-seven percent of Illinois voters op-posed a convention.

As in Michigan, voters in Iowa, Montana and Maryland will weigh reopening their state’s fundamental laws this November.

“Of the four states voting this time, I’ve seen the most support in Iowa,” said John Dinan, a political science professor at Wake Forest University in North Carolina.

In Iowa, the issue of marriage has dominated the conversation. The convention is supported by high-profi le Republicans and the Iowa Catholic Conference, who see it at as a chance to ban same-sex marriage. The Iowa Supreme Court legalized gay marriage last year.

But there is no particular hot topic driving Michigan’s referendum, and it’s still mainly a topic for political insiders, professors and lawyers.

“Some states have utilized lim-ited constitutional conventions in which legislators propose to voters looking at only certain matters, so you don’t get the hot-button stuff that can derail the whole project,” Williams said.

Beyond the fear factor of becom-ing worse off with a convention,

said Susan Fino, a political science professor at Wayne State University, the measure is ripe for “no” votes by default because it remains obscure to the general public.

“Political insiders, the attentive public, may be talking about a con-vention, but not the average voter,” said Fino. “I would place a hefty bet on it tanking unless turnout is low. If only those people with an ax to grind show up and turnout is below 40 percent, a convention may have a chance.”

Long oddsDinan said public indifference

was a factor in the previous eight referendums; so was pushback from political parties and groups that control the Legislature.

He said Rhode Island was the last state to hold a convention, in 1986 — two years after voting for it. He said it is the only state whose con-stitution requires a commission be established to review the issue and

advise the electorate.Dinan said such commissions,

which state governments can ap-point but rarely do, help ease fears about opening up the document by studying issues such as cost.

“Besides a preparatory commis-sion, one of the most important things in getting conventions passed is having the support of the governor or governor candidates,” Dinan said. “The support of a trusted statewide group can also help.”

Outside of the referendum, law-makers can make amendments and residents in 18 states, includ-ing Michigan, have the ability to put amendments on the ballot via signatures.

“Supporters are probably on the strongest ground when they argue the problems can’t be done piece-meal with amendments, but rather are rooted in the constitutional structure,” Dinan said.

E-mail: [email protected]

20*

16*20

10*20

20

20

10

1020

20*

920

20

This November, Michigan voters will be asked whether they want to call for a constitutional convention that would allow them to revise the state’s constitution.

*Besides Michigan,

voters in Iowa,

Maryland and Montana

have referendums

this year.

SOURCE: The Book of States 2010

Automatic referendum states

Voters in 14 states are automatically asked this question every nine, 10, 16 or 20 years, depending on their constitution.

WHAT OTHER STATES INDICATE ABOUT CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS

DON’T BET ON ITLAST STATE TO CONVENE WAS RHODE ISLAND — IN 1986

AP FILE PHOTO

Political career is born: George Romney gives his wife, Lenore, and son Mitt, 14, a hug at a Detroit news conference Feb. 10, 1962, after he announced he would seek the Republican nomination for governor of Michigan.

State’s last convention produced

a governorDelegate George Romney

had presidential ambitions; today so does his son

Convention firsts in 1961-62:Women, black delegates included

Yes, that’s a rolling pin:This cartoon accompanied an article in the Nov. 11, 1961, edition of The Grand Rapids Press that stated, “To read the present Constitution of Michigan, you wouldn’t know women exist, except as charity cases.”

PRESS PHOTO

JENNICE RICHARDSON: “I think we should reopen the constitution and make adjustments in various areas, such as education funding and judicial sentencing,” said Jennice Richardson, 44, of Grand Rapids, a hairstylist. “They (lawmakers) have not been doing the right things.”

THOM BELL: “I am open to the idea of recrafting the constitution, but I’m concerned the partisan divide will prevent any good constitutional

restructioning from happening,” said filmmaker Thom Bell, 55, of Grand Rapids, citing education and taxes as areas of need. “There are a lot of areas of how the state conducts its business of governance that need improvement and what’s making it difficult is the foundation.”

JOIN THE CONVERSATION:MLIVE.COM/MI10

WHAT READERS ARE SAYING

COMING MONDAYBuild your own constitution with our �step-by-step guideDoes the constitution really need to �be rewritten? Analysis by Peter LukeQ&A with leading opponents and �supporters of the constitutional convention

COMING TUESDAYDoes the proposal stand a chance �at the Nov. 2 election? We’ll have exclusive poll results.

Join a live chat 11:30 a.m. Tuesday with John Logie, left, former mayor of Grand Rapids and a leading constitutional convention proponent, and Rich Studley, president and CEO of the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, a leading opponent of the measure: mlive.com/mi10

ABOUT THIS SERIES

Michigan 10.0 was the name we gave The Press’ 10-part series that started Jan. 30. It was a play on words relating to software upgrades, but it also was meant to underscore that 2010 will be critical to creating a better version of our state. Every month since then, we explored key questions facing Michigan:

JANUARYHow do we get Michigan working?

FEBRUARYTime to pay the toll for roads?

MARCHShould we sell natural resources?

APRILTax changes could eliminateour deficit, but at what cost?

MAYIs it time to take some

communities off the map?

JUNECan our cities be cool?

JULYDo tax lures bring new jobs?

AUGUSTDo we need 550 school districts?

SEPTEMBERIs it time to consider becoming a

right-to-work state?

OCTOBERDo we need a new state constitution?

MISS AN INSTALLMENT?GO TO MLIVE.COM/MI10

Related Documents