34 November 2006 Working Paper DEPARTEMENT DE LA RECHERCHE Vocational Training in the Informal Sector Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey Research financed by GTZ (Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit) Richard Walther, ITG Consultant ([email protected]) Translation: Adam Ffoulkes Roberts Agence Française de Développement Direction de la Stratégie Département de la Recherche 5 rue Roland Barthes 75012 Paris - France www.afd.fr

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

AgenceFrançaisedeDéveloppement

34November 2006

AgenceFrançaisedeDéveloppement

WorkingPaper

DEPARTEMENT DE LA RECHERCHE

Vocational Training in the Informal SectorReport on the Ethiopia Field Survey

Research financed by GTZ(Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit)

Richard Walther, ITG Consultant([email protected])

Translation: Adam Ffoulkes Roberts

Agence Française de Développement

Direction de la Stratégie

Département de la Recherche

5 rue Roland Barthes

75012 Paris - France

www.afd.fr

Foreword

This report is an integral part of the survey and analysis work launched by the Research Department of the French

Development Agency (Agence Française de Développement, AFD) on training in the informal sector in five African countries

(South Africa, Benin, Cameroon, Morocco and Senegal). It was commissioned by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and

uses the same working assumptions as those applied to the other countries studied. It is also complementary to the report on

Ethiopia, which was produced on behalf of the German technical co-operation agency (GTZ) and also used the methodologi-

cal framework developed by the AFD.

The Angola field survey was carried out with extensive support from the French Embassy. However, the objectives could not

have been met without assistance from Emilio Ferreira and Fernando Madeira, experts with the firm HRD (Human Resources

Development) who helped the field survey mission to interpret the subtleties embedded in certain situations and accounts of

different experiences. Above all, they were able to convince certain people with little availability that they should provide the

survey team with information and analysis coming under their area of authority. The survey benefited from the expertise of

Anna Sofia Manzoni., who helped to identify the most legitimate Angolan representatives in the area studied and also provi-

ded her support in identifying documentary sources on the subject. The survey also benefited from the extremely useful help

of Abel Piqueras Candela, of the European Commission, who agreed to make a critical appraisal of the final report and nota-

bly checked that the sources quoted really do reflect the most recent changes in the country’s education and vocational trai-

ning policies.

Lastly, this report was also able to draw on extensive and very useful documentation, notably thanks to the representatives of

the European Commission Delegation, the UNDP, the DW, USAID and IDIA. They are very warmly thanked for their contribu-

tions.

� Working Paper N° 15 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Concept Note.

� Working Paper N° 16 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector – Report on the Morocco Field Survey.

� Working Paper N° 17 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector – Report on the Cameroon Field Survey.

� Working Paper N° 19 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector – Report on the Benin Field Survey.

� Working Paper N° 21 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector – Report on the Senegal Field Survey.

� Working Paper N° 30 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector – Report on the South Africa Field Survey.

� Working Paper N° 34 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector – Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey.

� Working Paper N° 35 : Vocational Training in the Informal Sector – Report on the Angola Field Survey.

The Ethiopian case study has been produced by the GTZ in partnership with the AFD as a part of efforts to align the action of

French and German development agencies.

Disclaimer

The analysis and conclusions of this document are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the official position of

the AFD or its partner institutions.

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 2

Table of contents

1. Introduction: Ethiopia, a country waking up to the reality of the informal sector 4

1.1. How the survey was carried out 4

1.2. The contribution of existing reports and studies 5

2. The country’s economic and social challenges 7

2.1. Growth is strong, but vulnerable to climatic and political conditions 7

2.2. Persistent poverty 8

2.3. Major educational needs 9

2.4. An essentially rural and informal labour force 11

2.4.1. A strong contrast between rural and urban activities 11

2.4.2. Difficulties in appraising the informal sector as a whole 12

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and social challenges 15

3.1. Current state of TVET 15

3.2. Towards a reform focusing on those concerned in the informal economy 16

3.2.1. The main thrust of the reform 17

3.2.2. The reform implementation process 18

3.2.3. The challenges of reform: moving from an institutional to a grassroots approach 22

4. Current training initiatives in the informal sector 23

4.1. The reality of traditional apprenticeship – a difficult issue 23

4.2. Public policies targeting the creation of micro activities 24

4.2.1. FEMSEDA entrepreneur training 24

4.2.2. The Dire Dawa REMSEDA’s integration and support role 25

4.2.3. The Addis Ababa weavers’ training project (ILO) 27

4.2.4. On-site training for MSEs in the building sector (GTZ) 29

4.3. The strategic role of women in the informal sector 30

4.3.1. The ILO survey and the profile of women entrepreneurs 30

4.3.2. Dire Dawa Women Entrepreneurs Association (DDWEA) 31

4.3.3. Dire Dawa Women’s Association (DDWA) 31

4.3.4. A training programme for empowering women 32

4.4. Varied experiences from the world of agriculture 32

4.4.1. The highly informal nature of employment in rural areas 33

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 3

4.4.2. Training farmers and agricultural development officials 33

4.4.3. Training the rural population in community skills training centres (CSTC) 33

4.4.4. The innovative activities of the Harar technical and agricultural training centre 35

4.4.5. NGO actions 37

5. Future developments and actions 39

5.1. TVET reform and the opportunities for the informal sector 39

5.1.1. Training institutions can ensure that training becomes an effective aspect of socialand economic development 39

5.1.2. The TVET system: skills assessment and certification for informal sector workers 41

5.2. The outreach of reform in the informal sector 42

5.2.1. The low impact of the training system on the informal sector 42

5.2.2. TVET reform and the lack of recognition of skills development processes in the informal economy 43

5.2.3. A paradigm shift with limited effects 43

5.3. The challenge of revitalising the informal sector 44

5.3.1. Looking closely at the real potential of traditional apprenticeship and self-learning methods 44

5.3.2. The need for a qualitative analysis of informal economy occupations 45

5.3.3. The need to go through with plans to recognise skills acquired in the informal sector 45

5.3.4. The need to strengthen sectoral, territorial and institutional dynamics 45

5.3.5. How to have informal sector workers take on responsibility for their own training and skills 46

In conclusion: the need to refocus the reform on grassroots initiatives 48

Appendix: recommendations and proposals for action 49

List of acronyms and abbreviations 51

References 52

Table of contents

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 4

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 5

The Ethiopian government is undertaking a complete

reform of its education and vocational training system and

wants the informal sector to be included in any changes.

This is an ambitious strategy, which will entail a complete

overhaul of the education and training system, focusing on

outcomes and responding to the economy’s needs, thus

contributing to the country’s development. It will also mean

integrating the different kinds of training systems (formal,

non-formal, informal) into an overall approach focusing on

skills that have previously acquired, through whichever

means. This shift from a unified system to a flexible and

modular one, and from a qualification-based paradigm to

one based on acquired vocational skills, offers a real oppor-

tunity for those working in the informal sector to obtain

recognised qualifications. The reform notably includes

plans for Centres of Competence whose purpose will be to

acknowledge not only skills acquired through experience

and work, but also those obtained through the various exist-

ing types of training.

However, the inclusion of informal sector workers among

the beneficiaries of the reform is not as easy as it sounds.

The various officials met during the survey will have to

acknowledge the reality of the informal sector and econo-

my. This will not come easily. During our interviews, for

example, it was difficult, if not impossible, to obtain precise

figures concerning the informal sector’s role in the labour

market or its contribution to national wealth. It was even

more difficult to gain any idea of the real situation concern-

ing production and service activities in the informal sector,

or to identify the traditional methods used for acquiring

knowledge and know-how. Differing opinions were

expressed and there was much debate as to the existence

or otherwise of traditional forms of apprenticeship. It was as

if the informal sector was viewed in terms of the role

assigned to it by the reform, rather than by taking account

of the actual situation and trends.

In this respect, Ethiopia is at a crossroads. Domestic work-

ers, women involved in income-generating activities, street

vendors, small-holders vulnerable to the vagaries of the

weather and all the micro-enterprises involved in production

and service activities will not see any lasting improvement

in their situation unless the reform acknowledges the reali-

ty of this situation and take steps to improve it. Moreover,

the reform will not succeed in achieving its aim of training

all those involved in economic production unless it takes

account of the sector as it exists, and, more importantly,

unless it involves and exploits the potential of existing

stakeholders, partners and trends.

The operational success of the current reform will undoubt-

edly enable Ethiopia’s informal sector to shift from a para-

digm of mere survival to one of growth and development.

However, this will only happen if the reform, which is

designed to facilitate the recognition and accreditation of

the sector’s human and vocational capital, first of all helps

to develop and enhance what already exists instead of pur-

suing its own training agenda.

1. Introduction: Ethiopia, a country waking up to the realityof the informal sector

1. Introduction: Ethiopia, a country waking up to the reality of the informal sector

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 6

The Ethiopia field survey differs from those carried out in

the other countries in that it is the result of a fruitful part-

nership between German and French development agen-

cies, namely the German Technical Co-operation Agency

(Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit - GTZ),

which provides technical assistance to the Ethiopian

authorities in the design and delivery of the reform of tech-

nical and vocational education and training (TVET), and the

French development agency (Agence Française de

Développement – AFD), which has overall responsibility for

the study on vocational training in the informal sector.

The Ethiopia survey reflects the desire of the German and

French agencies to align their thinking and efforts in the

education and training field. It was funded under the Ethio-

German TVET project, which started in 1999, and was

organised further to a joint agreement between the

Ethiopian education authorities and German technical

assistance providers. The various German development aid

agencies constitute the largest donor and support provider

in the current process of vocational training reform.1 The

survey was carried out between 5 and 16 September 2006.

It started in Addis Ababa, where meetings were held with

the various officials responsible at federal and regional lev-

els in the various ministries involved in vocational training.

Meetings took place with the major international organisa-

tions involved in this field, as well as with national employ-

ers’ and trade union federations. It was also possible to

meet some of the actors working closely with those eco-

nomically and professionally active in the informal sector.

After the interviews in the capital, the survey was complet-

ed by a field trip to the Dire Dawa region, where it was pos-

sible to interview project leaders working with micro-enter-

prises and production and service units, as well as some of

the workers who actually benefited from the training and

skills development activities. These meetings were particu-

larly useful in that they shed light on the real situation in the

informal economy and the way in which those working in it

are trying to raise themselves above subsistence level.

1.1. How the survey was carried out

1.2. The contribution of existing reports and studies

Unlike Morocco and Cameroon, Ethiopia has not undertak-

en any specific national surveys on the informal economy.

Neither has Addis Ababa been the subject of a specific sur-

vey such as those carried out for the major capital cities of

West Africa.2 However, the 2005 Labour Force Survey car-

ried out by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia3

provides some data which can be used to make an objec-

tive appraisal of the significance and role of those working

in the informal sector.

However, current data and forecast trends concerning the

economic, social and educational situation are widely avail-

able. The Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development

to End Poverty (PASDEP),4 published in October 2005, fol-

lows on from the Sustainable Development and Poverty

Reduction Program (SDPRP).5 It describes in detail the

progress made since 2000 and sets out the major policies

and means required to enable Ethiopia to achieve econom-

ic growth and reduce poverty. It also includes useful data for

this study, notably regarding what is happening in the edu-

cation and training area and how efforts to boost micro and

small enterprises (MSEs) can improve national economic

growth and reduce unemployment, and on the strategic

sectors and market niches which have job growth potential.

This plan thus combines economic strategy, a skills devel-

1 German technical assistance in the reform of TVET is being supported by most institutionsor organisations specialised in international development aid: the Centre for InternationalMigration (Center für Internationale Migration - CIM), the German Development Service(Deutscher Entwicklungsdienst - DED), Capacity Building International (InternationaleWeiterbildung und Entwicklung gGmbh - InWEnt) and Senior Expert Service (SES). TheGTZ, which is the technical cooperation agency, is responsible for coordinating all of thepartners involved. The German Development Bank KfW also provides financial support forsome parts of the reform programme.

2 STATECO, (2005), Méthodes statistiques et économiques pour le développement et latransition, No. 99.

3 Central Statistical Agency, (2006), The 2005 Labour Force Survey.

4 Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED), (2005), Ethiopia: Building onProgress: A Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP)(2005/6-2009/10).

5 The Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction Program (SDPRP) covered theyears 2000/01-2003/04.

1. Introduction: Ethiopia, a country waking up to the reality of the informal sector

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 7

6 Ministry of Education, (2005), Education Sector Development Program (ESDP-III),2005/2006-2010, Program Action Plan (PAP).

7 Ministry of Education (September 2006), National Technical and Vocational Education andTraining (TVET) Strategy.

8 Engineering Capacity Building Program (ECPB, July 2006), Non-Formal TVETImplementation Framework, Building Ethiopia.

opment strategy, and the inclusion of informal sector work-

ers in the vision of the country’s future.

The third phase of the Education Sector Development

Program (ESDP-III),6 which follows on from a programme

initially launched by the Ethiopian Government in 1997,

gives an overview of the education system and explains in

detail how training and education policies are contributing

to the overall strategy for boosting growth and reducing

poverty.

Information on the current TVET reform may be found in a

number of reports, the most important of which is the

National Technical and Vocational Education and Training

(TVET) Strategy.7 The latest version of this report was

being completed during our survey. The document sets out

and explains the reform’s key guidelines and the various

phases of its development. The reform’s implementation

framework, notably regarding the inclusion of non-formal

training in the future TVET system, is dealt with in a sepa-

rate document which has been produced by the Education

Ministry with German technical assistance.8

All of these documents, which are constantly being updat-

ed, clearly show that the inclusion of vocational training in

the country’s development strategy, and notably efforts to

recognise the informal sector’s role and skills needs, is at

the heart of the political agenda.

The only things missing from this comprehensive bibliogra-

phy are a very detailed analysis of the informal sector/econ-

omy, and an objective picture of its contribution to the coun-

try’s growth and poverty-reduction policy.

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 8

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

Ethiopia’s informal sector is part of an economy that

remains heavily dependent on the primary sector, although

a noticeable shift towards services and production activities

is under way. It has also been fully included in the policy to

combat poverty and reduce illiteracy and under-education

rates among the population.

2.1. Growth is strong, but vulnerable to climatic and political conditions

Since the Federal State was established in 1994, Ethiopia

has enjoyed a relatively sustained rate of growth, signifi-

cantly above that of Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole.

However, this rate suddenly fell from 8.8% to 2.7% in 2002,

and there was negative growth in 2003 (-3.7%). This was

due to the drought that afflicted the country in 2002/2003.

Economic growth then peaked at an unprecedented 13.1%

in 2004, mainly due to the quick recovery of agricultural pro-

duction. According to the OECD, the Ethiopian economy

should continue to show good results following the 2004

peak. Economic growth for 2004/2005 was 6.8% and a rate

of 5.8% has been forecast for 2005/2006.

Table 1. GDP growth: Ethiopia and Sub-Saharan Africa

1990 1995 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

CGDP (current prices, in billions of dollars), Ethiopia 8.61 5.78 6.53 6.51 6.06 6.65 8

GDP (current prices, in billions of dollars) Sub-Saharan Africa 298.38 317.52 326.24 324.87 337.21 439.29 ..

Annual GDP growth, Ethiopia (%) 2.6 6.1 6.0 8.8 2.7 -3.7 13.1

Annual GDP growth, Sub-Saharan Africa (%) L 3.8 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.9 4.8

GDP per capita (in constant 2000 dollars), Ethiopia 94.7 90.2 101.5 108.0 108.6 102.4 ..

Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, Ethiopia 170 110 110 110 100 90 110

Source: World Bank (2005), World Development Indicators.

The Ethiopian economy is heavily driven by the agricultural

sector, which represented 42.1% of GDP in 2004,9 employs

80% of the population (89% in 2001 according to World

Bank figures) and provides around 90% of export revenue.

The estimated increase in agricultural production is 6.6% in

2004/2005, and 7.4% in 2005/2006 and 2006/2007.

Agriculture receives support from public aid programmes

such as the national food security programme, and benefits

from the extension of public services to rural areas and the

protection of farmers’ rights. However, given the constraints

affecting agricultural markets (partially due to the lack of

roads), low levels of productivity (due to the limited use of

pesticides and fertilisers, irregular rainfall, poor soil fertility,

and environmental degradation)10 as well as chronic short-

ages of foodstuffs, the OECD estimates that approximately

5 million Ethiopians continue to depend on food aid.

Services represented 46.5% of GDP in 2004. This sector

grew by approximately 7% between 2004 and 2005, chiefly

9 OECD (2006), African Economic Outlook 2005/2006 – Country Studies: Ethiopia.

10 World Food Programme (2006), Draft County Programme - Ethiopia 10430.0 (2007-2011).

as a result of the growth in the health and education sec-

tors, as well as in transport and communications.

Industry, which represented 11.4% of GDP in 2004, showed

real growth of approximately 7% over the 2004/2005 peri-

od. This was mainly generated by a high level of household

and business demand for construction services, and the

development of the mining and quarrying industries.

Growth in service activities and a genuinely modern indus-

try appears to be constrained by the fact that Ethiopia has

a predominantly public sector economy and is finding it dif-

ficult to introduce effective privatisation policies.

The country has considerable unexploited resources

(hydroelectricity, minerals, tourism, etc.) There are a num-

ber of growth niches just waiting to be exploited. 2004 saw

the rapid emergence of a horticultural sector, which contin-

ued to show strong signs of growth in 2005.11

Ethiopia’s balance of trade has a structural deficit. Exports

are essentially generated by coffee (Ethiopia is the world’s

sixth largest producer), where the downward trend in prices

is likely to continue in view of the global surplus.

Conversely, the increase in import prices, in particular of oil

and steel, has worsened the country’s trade deficit, which

reached 20.4% of GDP in 2003/2004. Ethiopia relies on

multilateral and bilateral international funding to cover its

budget deficit and also to finance part of its investment pro-

gramme.

The present economic situation is however threatened by

recent political developments. The violence that broke out

as a result of the contested election results in May 2005,

and the ensuing brutal repression of the opposition, jeopar-

dised political stability and led to the freezing of part of the

international aid budget ($375 million in December 2005,

which is equivalent to 10% of the country’s revenue).12 The

growing risk of conflict with Eritrea should also be stressed;

there has been a constant increase in tension between the

two countries in recent years, despite the peace agreement

signed in December 2000.

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 9

Table 2. GDP in 2004, by sector

As a % of Ethiopia’s GDP

Agriculture 42.1

Manufacturing industries 4.6

Other industries 6.8

Trade, hotels and restaurants 8.6

Transport, storage and communications 7.0

Public services 14.7

Other services 16.2

Source: AfDB/OECD 2006.

2.2. Persistent poverty

Table 3. Growth of GDP per capita

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006(estimated) (anticipated)

GDP per capita, in dollars 120 109 115 137 153 170

GDP per capita in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) 723 727 691 769 823 858

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Apart from the 2002/2003 period when Ethiopia faced a

general economic slowdown, GDP per capita has been

gradually and consistently increasing over recent years.

However, in spite of this encouraging economic perform-

ance, Ethiopia remains one of the poorest countries in the

world. It was ranked 170th out of 177 countries in the

UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) in 2005.13

Despite the constant increase in Ethiopia’s HDI, a large

section of the population continues to live in poverty. In

2000, 77.8% of Ethiopians lived on less than $2 a day, and

23% were living under the absolute poverty level ($1 a day).

11 Mission économique d’Addis-Abeba (2006), Fiche pays Ethiopie, MINEFI-DGTPE.

12 OECD, op. cit.

13 UNDP, (2005), Human Development Report.

Studies carried out under the PASDEP show that average

growth of 4% over the coming years would not be enough

to reduce the level of absolute poverty. At this rate of

growth, more than 20 million Ethiopians will still be living in

poverty in 2015. An annual growth of at least 8% would be

needed to achieve the Millennium Goals to cut current

poverty levels by half.

Ethiopia is thus one of Africa’s chief recipients of World

Bank and EU development aid. In 2004, Ethiopia received

aid worth a total of $1.2 billion, which is approximately

equivalent to 16% of its GDP14.

Under the PASDEP’s current phase (2006-2011), it should

be possible to improve the current situation thanks to

increased productivity growth in agriculture, improved man-

agement of natural resources, food security and diversifica-

tion of the means of subsistence.15

Ethiopia also benefits from the Heavily Indebted Poor

Countries (HIPC) Initiative. It completed the process on 20

April 2004, thus opening the way for cancellation of multi-

lateral debt. This has permitted rescheduling which has

resulted in a reduction of nearly 80% of Ethiopia’s foreign

debt.16

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 10

2.3. Major educational needs

According to data from the National Population Office (2005),

Ethiopia has a population of 73 million. The country has had

an annual demographic growth rate of nearly 2.5% over the

last decade, which has now settled at 1.9% (World Bank,

2006). This means that Ethiopia has a young population

(45.4% of the population—in other words about 31.2 million

people—was aged under 14 in 2003), and that considerable

investment is thus needed in the education system.

In view of this situation, the Ethiopian government adopted

an education and training policy, from 1994 onwards. With

UNESCO’s help, it drew up a ten-year Education Sector

Development Programme (ESDP). The country is currently

in the third phase of this programme (ESDP III), which runs

from 2005 to 2011. The main aim of the programme is to

achieve the Millennium Goals through improved access to

Table 4. Literacy rates, Ethiopia compared with Sub-Saharan Africa

Ethiopia Sub-Saharan Africa

Literacy rate (% of people aged 15 and over) (2000-2004) 49.9 62.5

Female literacy rate (% of women aged 15 and over) (2000-2004) 40.3 54.8

Male literacy rate (% of men aged 15 and over) (2000-2004) 60 70.9

Youth literacy rate (% of 15- to 24-year olds) (2001) 67.5 70.5

Literacy rate of young women (% of 15- to 24-year old young women) (2001) 60.2 65.7

Literacy rate of young men (% of 15- to 24-year old young men) (2001) 74.8 75.7

Source: UNESCO, Institute of Statistics.

education and better quality teaching.

There are considerable challenges to be met in terms of lit-

eracy. According to UNDP data, Ethiopia’s illiteracy rates

were among the highest in the world until the mid-1970s.

UNESCO data for 2000-200417 shows that adult literacy

rates remain 12.6 points lower than the average for Sub-

Saharan Africa, and that there is a gap of nearly 20 points

between male and female literacy rates. They also show

however that literacy among young people aged between

15 and 24 is clearly on the increase, and that the disparities

between Ethiopia and the other countries of Sub-Saharan

Africa, and between young men and young women in

Ethiopia, are gradually being reduced thanks to the efforts

14 Mission économique d’Addis-Abeba, Fiche pays Ethiopie, MINEFI-DGTPE.

15 World Food Programme (2006), op.cit.

16 Mission économique, op. cit.

17 UNESCO’s data are more encouraging than those in the PASDEP (Plan for Acceleratedand Sustained Development to End Poverty), which indicates that in 2004, 62% ofEthiopians were illiterate.

the country is making in order to develop its education sec-

tor. However, there are still significant disparities between

rural and urban areas, and these also need to be reduced.

UNESCO’s analysis of the net enrolment ratio18 shows that,

despite progress made in the area of literacy, education lev-

els in Ethiopia remain below those for Sub-Saharan Africa.

This net enrolment ratio is low for primary education com-

pared to other countries, remaining at under 50% of children

of school age. The repetition rate in primary education is rel-

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 11

Table 5. Progression and achievements in the education system (2004)

Ethiopia

Average number of years’ education ISCED20 1-6 years 6 (UIS estimate)

Repetition rate, primary education (%) 11

Survival rate into the grade for 10- to 11-year-olds (%) (2000-2004)21 62

Rate of transition from primary to secondary education (%) 85

Source: UNESCO, Institute of Statistics.

Table 6. Primary and secondary school net enrolment ratios (2004)

Ethiopia Sub-Saharan Africa

Net enrolment ratio, primary school (%) 46 65

Net enrolment ratio of girls, primary school (%) 44 63

Net enrolment ratio of boys, primary school (%) 49 67

Net enrolment ratio, secondary school (UIS estimate,22%) 25 24

Net enrolment ratio of girls, secondary school (UIS estimate, %) 19 21

Net enrolment ratio of boys, secondary school (UIS estimate, %) 31 26

Source: UNESCO, Institute of Statistics.

atively low (11%) and the survival rate is 62% of children.19

However, in secondary education the net enrolment ratio is

around 25% of the age range concerned. This puts Ethiopia

at the same level as the average for Sub-Saharan Africa.

One of the reasons for this situation is the relatively high

transition rate from primary to secondary education; this

was 85% in 2004.

The data provided by the PASDEP reinforce those provid-

ed by UNESCO.23 They show a gross enrolment ratio24 of

79.2% in 2004/05 (70.9% for girls and 87.3% for boys).

They also highlight extremely wide inter-regional dispari-

ties, with a rate of 125% for Addis Ababa compared with a

rate of 75 to 80% for the regions of Amhara and Dire Dawa,

and only 15 to 17% for the regions of Afar and Somalia.

Lastly, they show that between 1997 (the year the first

ESDP was launched) and the current phase of ESDP III,

the number of primary schools in Ethiopia rose from 10,394

to 16,078. This increase has however been coupled with a

rise in the teacher/pupil ratio. This stood at 57 in 1997 and

has risen to 69 in 2005 (compared to an average of 44 in

Sub-Saharan Africa), despite the aims of the successive

programmes to bring it down to 50.

Although Ethiopia spends an average of 4.6% of its GDP on

18 The net enrolment ratio is the percentage of enrolled children of the official age for the edu-cation level indicated to the total population of that age. Net enrolment ratios exceeding100% reflect discrepancies between these two data sets (UNDP, (2003), HumanDevelopment Report).

19 According to 2006 World Bank data, the survival rate is only 51%, which would consider-ably weaken the efficiency of the Ethiopian education system.

20 International Standard Classification of Education.

21 UNICEF.

22 UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

23 Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED) (2005), Ethiopia: Building onProgress: A Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP)(2005/6-2009/10).

24 The gross enrolment ratio is the percentage of total number of children enrolled in primaryeducation, irrespective of age, and the population of the age group of those officially eligi-ble for primary education in any given year. This indicator is widely used to assess theoverall level of participation in primary education and the capacity of the education systemto satisfy primary education needs (UNESCO).

education, a figure that puts the country in the higher brack-

et in terms of education spending across the region, con-

siderable efforts are still needed. However, the number of

teachers is appallingly low in relation to the number of chil-

dren of school age. According to the Ministry of Education,

the lack of teachers is the main factor hindering the

increase in primary education enrolment. This is why there

are plans, under ESDP III, to recruit 294,760 teachers with

a view to educating a maximum number of children and

reducing the teacher/pupil ratio to acceptable levels.

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 12

2.4. An essentially rural and informal labour force

The Labour Force Survey (LFS), carried out in 2005 by the

CSA,25 indicates a participation rate of the economically

active population (including all those over 10 years old) of

76.7% over the twelve months preceding the survey.

However, this figure varies widely according to gender and

areas of activity. For example, the participation rate is only

50.2% in urban areas, whereas it reaches 82% in rural

areas. The rate for men is 84.7% compared to 69% for

women. Similar differences can be seen as far as unem-

ployment is concerned.26 The rate of unemployment is

20.6% in cities, but only 2.6% in rural areas. There is bare-

ly any male unemployment in rural areas (0.9%), although

it is high in urban areas (13.7%). Female unemployment is

very high in urban areas (27.2%), but low in rural areas

(4.6%).

2.4.1. A strong contrast between rural and

urban activities

Analysis of the economically active population by cate-

gories of employment highlights differences between sec-

tors, in particular agriculture/fishing and services, as well as

between the kinds of jobs held by those working in these

sectors. These include skilled workers, workers doing ele-

mentary jobs (mainly in manufacturing), craftworkers and

Table 7. Breakdown of the economically active population by categories of workers

Categories of workers Overall participation rate Participation rate in urban areas Participation rate in rural areas

Those working in services or trade 6.7 24.8 4.5

Qualified workers in agriculture and fishing 40.5 8.2 44.5

Elementary jobs27 42.8 24.6 45.1

Crafts and related activities 7.0 22.6 5.1

Technicians and similar

workers 1.0 5.5 0.4

Others 2.0 14.3 0.4

Source: National Labour Force Survey, 2005.

technicians.

The breakdown by categories of activity/types of jobs con-

firms the fact that Ethiopia’s economy is heavily dependent

on the rural and agricultural sector (which employs more

than 25 million people out of a total economically active

population of 35 million). It also indicates that non-agricul-

tural service and production activities are mainly concen-

trated in urban areas. From this we can infer that the grow-

ing urbanisation of Ethiopia, which currently has one of the

highest rural population rates in the whole of Africa (85% of

total population and 90% of the population living under the

poverty level currently live in rural areas)28 will have a sig-

nificant impact on the type of work done by the economi-

cally active population. Service, crafts and technical activi-

ties are also likely to grow.

25 Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (2006), The 2005 National Labour Force Survey.

26 According to the person in charge of the LFS, the concept of unemployment used inEthiopia is that of flexible unemployment. This defines the unemployed as those who areavailable for work whereas the strict definition used by the ILO is unemployed people avail-able for work and looking for work.

27 The survey defines elementary activities as those carried out by day labourers in agricul-ture, mining or building.

28 ECPB (2006), National Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)Strategy.

According to the survey, the distinction between skilled and

elementary activities does not appear to correspond to the

usual skills levels. It rather suggests that skilled workers in

agriculture and fishing have a fixed professional activity,

whereas workers classed in the elementary jobs category

are day labourers who change jobs depending on the work

available mainly in manufacturing. According to the survey

on the informal urban sector published in 2003,29 the term

“elementary job” refers to routine tasks that are usually of a

manual nature and require physical effort. Examples given

in the survey include street, market or door-to-door sales,

various kinds of washing and cleaning activities, cleaning

and maintenance in houses, hotels and offices, portering,

etc.

2.4.2. Difficulties in appraising the informal sec-

tor as a whole

The statistical data available (LFS 2005 and Informal Sector

Survey 2003) provide a detailed overview of Ethiopia’s

labour market, given that the two surveys furnish significant

data on the breakdown of the workforce and the respective

shares of types of activity according to a large number of cri-

teria. Amajor problem still remains, however, concerning the

identification of those working in the informal sector. The

concept used by the CSA only applies to urban areas, and it

is only possible to gain an overall view of the non-structured

economy by analogy, in other words by applying the

Agency’s indicators for urban areas to the rural sector.

A labour market dominated by domestic jobs and self-

employment

The Labour Force Survey gives a detailed analysis of

employment status in Ethiopia, indicating in particular that

the majority of the economically active population is either

unpaid family workers (50.3%) or self-employees/own

account workers (40.9%). Although the available data does

not enable any precise classification of these workers, there

is no doubt that most of the activities covered here are infor-

mal, in that they are above all based on occasional employ-

ment (according to the term “day labourer” used to define

elementary activities), family, personal or social links

(unpaid family workers) rather than jobs covered by a prop-

er employment agreement including guarantees.30 The

table on the breakdown of the economically active popula-

tion according to employment status shows that at most

8.8% have salaried employee status and thus the possibili-

ty of a formal employment contract.

On the basis of these data, it is impossible to say that all

jobs outside public administration and private enterprises

are in the informal economy, although there are strong

grounds for presuming this to be the case. The results of

the 2003 Informal Sector Survey31 make it easier to give an

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 13

Table 8. Breakdown of the economically active population according to type of employment

Employee status As a % of overall As a % of urban As a % of ruralparticipation/activity rate participation/activity rate participation/activity rate

Government employees 2.6 16.5 0.9

Self-employees/own account workers 40.9 40.3 41.0

Unpaid family workers 50.3 15.0 54.6

Private organisation 2.9 15.1 1.4

Others 3.3 13.1 3.5

Source: National Labour Force Survey, 2005.

accurate interpretation of the 2005 survey on the real situ-

ation in the overall labour market.

Those working in the informal sector do so by necessity,

are left to themselves, and are mainly self-taught

In its introduction to the Informal Sector Survey, the

Statistical Agency defines the informal sector as existing in

a specific context (urban areas only). It also uses multiple

criteria that are much wider than simply a business with no

29 Central Statistical Agency (2003), Report on Urban Informal Sector, Sample Survey.

30 See the definition of informal employment in R. Walther, (2006), La formation en secteurinformel, Note de problématique, AFD Working Paper No.15.

31 Central Statistical Agency (2003), Op.cit.

specific accounting system: the definition used in the sur-

veys identified in the other countries visited. The basic def-

inition used is that the informal sector refers to activities

which are carried out in the home or in a single-person

enterprise by the owner alone or by the owner and a very

small number of employees. The wider definition includes

the following criteria:

� the informal enterprise is not usually officially registered

and has a low level of organisation, productivity, and

profitability;

� it has limited access to the market, to credit agencies, to

formal training and to public services;

� it has very small or no fixed premises, and is usually

located in the family’s home;

� it is not recognised, supported or regulated by the pub-

lic authorities and does not comply with social protec-

tion regulations, employment legislation or health and

safety provisions.

Results of the 2003 survey on the informal sector are the

following:

� informal enterprises employ 50.6% of the urban eco-

nomically active population;

� out of the 799,352 people interviewed as part of the sur-

vey, 43.29% work in manufacturing and 37.78% in the

trade or hotel and catering sectors;

� 99.09% of enterprises have a single owner. Ownership

is based on a structured partnership in only 0.56% of

cases. Although the survey states that co-operatives

and associations are on the increase, these presently

represent only a very small percentage of informal

enterprises;

� the capital of informal enterprises is made up of 90%

personal or family capital. 0.12% have obtained a bank

loan, 0.74% have received funding from micro-credit

organisations, and 1.04% receive support/funding from

public authorities and/or NGOs;

� 63% of the value-added of the sector is generated by

trade and hotel and catering, and 25% by manufactur-

ing. Next by order of importance are personal services,

urban agriculture, and transport;

� people choose to work in the informal sector mainly

because they have no other alternative (41.73%) and/or

because little investment is required (36.73%). For only

4.54% is it a deliberate choice;

� workers in this sector acquire their skills through being

self-taught (67.86%), via their family (26.88%) or

through apprenticeship or on-the-job training (3.54%).

Only a very small percentage (0.09%) has received any

formal training.

An analysis of informal sector workers’ education levels and

the different methods of skills acquisition shows that only

46.95% are literate (compared with the national average of

49.9% for the same period), that 42.74% have completed

primary education (compared with 46% at national level)

and that only 13.01% of male workers have been through

secondary education, compared with 31% at national level.

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 14

Table 9. Analysis of the level of education of informal sector workers by gender (in %)

Total workforce and share by gender Illiterate Intermittent Years Years Years Over 12 Totalschool 1-6 7-8 9-12 illiterate

Men 32.50 5.03 16.45 13.48 13.01 0.71 67.50

Women 67.41 1.57 35.28 7.46 6.98 0.13 32.59

Total 53.05 2.99 24.19 9.46 9.46 0. 37 46.95

Source: Survey of the urban informal sector, 2003.

These figures show that the informal sector employs the

least educated men, and especially women, and that work-

ers with a higher level of education are more likely to be

able to find alternative employment to the informal sector.

They also show that only a very tiny number of workers

have taken part in TVET. It can be said therefore that, in

2003, TVET had almost no effect on the skills existing in the

informal sector.

A dominant and fast-growing informal sector

If the “informal unit” term used for urban areas is applied to

rural areas, it can be said that all of the jobs recorded in

2005 under the headings of self-employment, own-account

workers and unpaid family workers do, by analogy, come

under the informal sector. The percentage of informal work-

ers out of the total economically active population is thus

91.2%. This places Ethiopia alongside Cameroon, Benin

and Senegal as countries with a huge informal-type econo-

my employing at least 90% of the economically active pop-

ulation. This analysis is confirmed by the non-formal TVET

implementation framework programme drawn up by

German development aid agencies in co-operation with all

the Ethiopian authorities and training providers concerned.

It clearly indicates that the vast majority of employment

opportunities lie in the informal sector.32 The programme

also underlines that the creation and consolidation of

employment in Ethiopia cannot come from major public or

private companies, or from public administration, but nec-

essarily relies on the development of MSEs, especially in

the informal sector, and the promotion of viable forms of

self-employment. The statistical study on the informal sec-

tor also indicates that the informal economy is growing

rather than declining. According to the study, the economic

recession, structural adjustment policies, increasing urban-

isation and high population growth have led to the unantic-

ipated and unprecedented growth of the informal sector in

a number of developing countries. This is all the more so as

modern enterprises and especially public companies have

had to make workers redundant or make large cuts in

salaries. This partly explains the importance of the informal

sector in Ethiopia.

2. The country’s economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 15

32 ECBP (Engineering Capacity Building Program) (2006), Non-formal TVET implementa-tion framework, Building Ethiopia.

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 16

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and socialchallenges

The TVET system is currently the focus of an in-depth strate-

gic rethinking and a reform intended to provide the Ethiopian

economy with the skills it needs in order to grow. This rethink-

ing and reform process is part and parcel of an overarching

policy entitled “Building Ethiopia”, which is being implement-

ed by the Ethiopian Government under the supervision of the

Ministry of Capacity Building and in partnership with the

Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Trade and Industry and

the private sector. The Engineering Capacity Building

Program (ECBP)33 is responsible for the policy’s overall

implementation. It is funded by the German Ministry of

Economic Co-operation and Development (BMZ), and oper-

ates with assistance from various German aid agencies

under the co-ordination of the largest such agency, the GTZ.

The purpose of the overall programme is to reform voca-

tional training and engineering courses. It is also designed

to introduce a national framework for qualifications and

standards, to develop the private sector and to encourage

it to contribute to the various types of action being taken.

The reform of the TVET system is a key component in the

programme. This reform, which is just getting under way, is

being implemented as part of the ECBP by the Ministry of

Education with technical assistance from German aid agen-

cies, in conjunction with local and regional authorities and

with the co-operation of all the economic and social part-

ners concerned.

3.1. Current state of TVET

According to the Ethiopian Ministry, technical and vocation-

al education and training comprises three main types of

training:

� formal training schemes run by accredited public or pri-

vate vocational training centres and leading to recog-

nised technician-level certification;

� “non-formal” training courses,34 which do not meet

recognised standards relating to content and the neces-

sary length of training in order to obtain certification.

They are delivered by public or private institutions such

as NGOs, community training centres, religious agen-

cies and private profit-making bodies. Non-formal train-

ing focuses primarily on helping people obtain employ-

ment. It is aimed at school leavers, school dropouts,

young and adult workers and groups excluded from the

labour market;

� informal training, which refers to the acquisition of

knowledge and skills in a non-structured environment. It

consists primarily of on-the-job training that is not cur-

rently recognised or validated and traditional appren-

ticeships in MSEs, particularly in the craft sector.

33 As the term ECBP is commonly used in Ethiopia, it seems logical for this report to refer tothe Ethiopian capacity building programme in this way.

34 The definition of non-formal training given in the reference documents is taken fromCEDEFOP’s 2003 Glossary on Transparency and Validation of Non-Formal and InformalTraining. It defines non-formal training as “learning which is embedded in planned activi-ties that are not explicitly designated as learning (in terms of objectives, time or support),but which contain an important learning element. Non-formal learning is intentional fromthe learner’s perspective.” The strategic and operational papers mentioned define the con-cept of informal training along the same lines as CEDEFOP (learning resulting from every-day activities related to work, family or leisure, which in most cases is unintentional fromthe learner’s perspective), while incorporating it into the overarching concept of non-formaltraining.

Training is also available in the agricultural sector, but the

Ministry of Education is not responsible for it.

The following table outlines the structure of the formal

TVET system organised by the Ministry of Education.

In order to increase the availability of training for young

excluded people and school dropouts, over ten years ago,

the Government decided to expand the formal TVET sys-

tem. Thus the number of non-agricultural education and

training institutions rose from 17 to 199 between 1996/1997

and 2004/2005, and the number of pupils from 3,000 to

106,300,35 31% of whom are trained in private establish-

ments. In addition, approximately 42,000 young people

were enrolled in agricultural courses in 2004/2005.

However, notwithstanding the efforts made to extend TVET

in recent years, it caters for just 3% of the relevant age

group.

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 17

Table 10. The Education and TVET system in Ethiopia

Source: Ethio-German TVET Programme (2003), The Ethiopian TVET Qualification System, Addis Ababa.

Age

19 Higher Education

Diploma Level

Certificate Level II

Certificate Level I

Junior LevelTVET

Basic LevelVocational

Upper SecondarySchool

General SecondaryEducation

Primary Education

18

17

16

15

14

13

12

11

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

4

Grade

Despite these investments, and although it is difficult to esti-

mate the number of Ethiopians with access to TVET,

demand still far exceeds supply and most of the population

does not have access to such training—particularly school

dropouts, the unemployed, company employees, the self-

employed and workers employed in MSEs. In addition, the

system has a number of obvious weaknesses. In recent

years, for instance, many employers have lamented the

poor quality of teaching, trainees’ lack of practical skills and

the unsuitability of training programmes. Moreover, it has

not been possible until now for people having acquired

vocational skills outside the formal TVET system (through

traditional apprenticeships, non-formal training, exercising

an occupation and so on) to obtain recognised certification,

resulting inter alia in a lack of labour market transparency.

35 According to ESDP (Education Sector Development Programme) III. The first ESDP pro-gramme (ESDP I) was launched in 1997 as an integral part of the Civil Service ReformProgramme (CSRP). In fact, the purpose of the ESDP is to help the Ethiopian Governmentharness the full range of national and international resources in order to enhance the qual-ity and efficiency of the education system as a whole, and to report on the efforts made inthis area.

The strategic thrust of the reform was defined as part of the

implementation of the PASDEP and in the context of the var-

ious national and sector-specific economic development

plans. The public authorities responsible for overseeing it

with technical assistance from German aid agencies have

the task of training a skilled, motivated and competent work

force. The aim is to develop the private sector and introduce

education and training schemes geared to demand and tai-

lored to the economic and social needs of the labour market,

particularly with a view to creating self-employment opportu-

nities. The current reform thus directly focuses on upgrading

the skills of those employed in the informal economy.

3.2.1. The main thrust of the reform

The main thrust of the reform may be described as follows:

� broadly, it seeks to change the vocational training para-

digm by moving from a supply-driven approach to one

driven by demand and, more importantly, by the accred-

itation of existing skills, irrespective of how they have

been acquired;

� by turning the system around, it will improve access to

training among people who are usually excluded (young

people and adults who have dropped out of school,

have a low level of education or are illiterate, entrepre-

neurs and workers in the formal and informal economy

who need to upgrade their skills and obtain recognised

qualifications, farmers and agricultural workers, unem-

ployed people seeking skills in order to enter the labour

market, and so on);

� it is designed to gear training to MSEs, to encourage

training centres to concentrate on the informal econo-

my’s skills needs, to introduce incentives aimed at

encouraging business start-ups at local level and in par-

ticular linking the acquisition of skills to access to micro-

credit so as to create self-employment opportunities,

and, lastly, to enable the various training institutions to

develop training courses tailored to the needs of their

target groups.

At a more structural level, the current reform is intended to

ensure that non-formal training becomes an integral part

of the training system. This means that the new system

must explicitly define the objectives and content of such

training and specify operational procedures, and that all

the relevant partners must be involved in the planning,

management and assessment phases when it comes to

developing non-formal training provision. It also means

that the existing distinction between formal training lead-

ing to specific qualifications and non-formal training lead-

ing to unvalidated, unrecognised competencies and skills

must be abandoned. To this end, the reform proposes that

the entire training system be based on occupational stan-

dards as well as a single format for accrediting all different

types of courses. It also proposes that training be

assessed and certified on the basis of outcomes, that is,

the competencies actually acquired as a result of formal or

informal training and validated using a uniform certifica-

tion method and system.

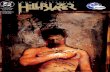

Figure 1 shows how the reform makes the transition from

supply-driven training to demand-led training, notably tak-

ing account of labour market needs. These needs are

reflected in, and organised into occupational standards

serving as a basis for the design of training curricula and

various modes of formal, non-formal, workplace, on-the-job

training and self-learning. If the system is to be successful,

a quality-management approach should be adopted during

the labour market analysis to ensure this is used effective-

ly to draw up occupational standards, and to incorporate

various forms of training into a service geared to the skills

development needs of individuals and businesses. `

According to the strategic and operational reference docu-

ments, delivery of the reform clearly calls for an overhaul of

all existing training schemes so as to tailor them to the com-

petencies and skills needed by the market, particularly in

the micro- and small enterprise sector. These schemes also

require institutional changes in line with the objectives to be

achieved. In particular, all private and public, economic and

social, and national and local partners must be involved

both in developing new training content and modes of train-

ing and in managing the overall training, assessment and

certification system.

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 18

3.2. Towards a reform focusing on those concerned in the informal economy

Figure 1. Outcome-based organisation of TVET system

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 19

3.2.2. The reform implementation process

Various strategic papers published since 2002 have gradu-

ally refined the reform process to be implemented, and out-

lined the main thrust of an operational scenario now being

developed. Various initial tangible outcomes were identified

during the field survey.

The decision to adopt a uniform approach to the reform

Various ministries are currently involved in Ethiopia’s TVET

sector on account of the institutions they are in charge of:

the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Agriculture, the

Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Trade and Industry and

the Ministry of Labour. The paper setting out the “National

Technical and Vocational Education and Training

Strategy”,36 the latest version of which has recently been

completed (in September 2006), has the distinctive feature

of covering all forms of technical and vocational training,

apart from higher education, irrespective of which particular

ministry they come under. The application of this across-

the-board strategy to all forms of training is innovative in

that it unites all the partners around a common vision of

what needs to be done in order for Ethiopia to ensure a

more competent and skilled work force, thereby improving

its chances of development and economic growth. Previous

field surveys carried out as part of the study on “Vocational

Training in the Informal Sector”, particularly the one on

Benin, showed that without such a common vision none of

the reforms instituted had any chance of being completed

within a reasonable timeframe. The field survey demon-

strated that such a common vision exists in Ethiopia as

regards the broad thrust of reform, but not necessarily in

relation to the specific means of delivery.

The issue of consultative or deliberative management of

the reform process

The strategy paper calls for a wide range of stakeholders at

all levels to be involved in implementing the different com-

ponents and phases of the reform process.

Source: Ministry of Education diagram, Draft Revised Strategy, 2006.

36 ECBP (2006), op.cit.

Labour Markett

regulated byTVET authorities

(withparticipation ofstakeholders)

OccupationalStandards

Support to curriculumdevelopment: curriculumguides, model curricula, etc

OccupationalTesting/

Certification

QualityManagement

TVETDelivery

Helping Hand

Formal TVETdelivered by publicand non-publicproviders, enterpris-es,as cooperativetraining, etc.

Long and short termnon-formal TVETprogrammesdelivered by publicand non-publicproviders, inenterprises, etc.

Informal TVET, i.e.on the job-training,self-learning,traditionalapprenticeship andall other modes ofTVET

The public authorities have opted for the greatest possible

representation of stakeholders. The partners normally

involved in consultation forums in other countries (min-

istries, employers, trade unions and sector bodies) are

included, but so are representatives of teachers, parents,

local authorities, the beneficiaries and leading national

communication agencies. As a result, some of the organi-

sations met with during the survey, particularly employers’

organisations and trade unions, feel that their voices cannot

be heard properly. The key consultation forums identified in

the strategic paper are the national and regional commit-

tees responsible for helping the authorities introduce the

reform according to the main guidelines set. A number of

those met mentioned the current debate over the proper

nature of these committees: will they continue to serve as

mere forums for expression and information sharing, or will

they, as many seem to hope, be given genuine decision-

making authority? It appears that employers, who have

trouble finding the time and motivation to take part in these

committees, will play an active role in them only if their func-

tion is deliberative rather than purely consultative.

The crucial need for a uniform approach to reorganising

demand, supply and certification

The fact that the reform focuses on outcomes (i.e. the com-

petencies acquired and certified) has led to a complete

overhaul of the training system by means of a process

divided into interlinked phases in terms of both methodolo-

gy and timeframe. This process may be described as fol-

lows:

� analysis of the labour market and business demands

culminates in the setting of occupational benchmarks

standardised at national level;

� these benchmarks, which identify the competencies to

be developed, serve as standards for the development

of training curricula and quality management of the var-

ious training mechanisms (formal, non-formal and infor-

mal) introduced;

� both training outcomes and competencies acquired on

the job are assessed and certified in relation to the stan-

dardised occupational benchmarks;

� assessment and certification give access to recognised

national qualifications, which are identical regardless of

how they are gained (through training or the validation

of competencies acquired on the job).37

The reform project sets out procedures for implementing

each of these phases. For instance, the task of analysing

demand is described as being the joint responsibility of

training centres and employers. The federal authorities are

responsible for setting occupational benchmarks, although

employers and trade unions must also be consulted and

actively involved, and contributions must be sought from

experts who are knowledgeable about the world of work.

Curriculum development is assigned to experts within train-

ing centres, whose sole obligation is to produce modular

courses leading to the outcomes identified by the corre-

sponding benchmarks.38 Assessment and certification, car-

ried out on an independent basis at the Centres of

Competence still to be set up, undoubtedly form the cen-

trepiece of the entire reform. By assessing competencies

rather than the knowledge acquired during training courses,

the system as a whole can focus on the new target groups:

as well as graduates of formal and non-formal training

schemes, these include apprentices, workers trained on the

job and, by extension, those employed in the informal sec-

tor, many of whom have no educational qualifications other

than proven occupational know-how.

The field survey was able to verify that the reform imple-

mentation scenario was not merely hypothetical, but had

actually begun to take shape, particularly in the construc-

tion sector, which is regarded as a priority. Some bench-

marks for occupations in areas such as structural work, fin-

ishing work and interior fittings have been finalised.39While

the curricula for these benchmarks are not yet finished, they

are at least in the process of being completed. The experts

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 20

37 The “Engineering Capacity Building Program, National Training Qualification Framework”paper gives a very clear picture of the overall qualification framework on which the currentreform is based. As well as outlining the process of moving from labour-market analysis tocertification by means of occupational benchmarks and assessment of the competenciesacquired, it explains the different qualification levels: basic level, junior level, intermediatelevels I and II (leading to certificates) and intermediate level (leading to a diploma). Itshows that the qualification framework does not go beyond the recognition of technician-level diplomas, to use the terminology employed by the European Union.

38 Although training centres are responsible for curriculum development, they receive initialassistance from the Ministry of Education. It sends them “model curricula” developed at thecentral level, which they can adopt and/or adapt according to their own situation andneeds.

39 According to the PASDEP, more than 50 occupational benchmarks had been set by theend of 2005.

responsible for testing and certifying them have received

methodological training. All that remains is to set up the

Centres of Competence at Entoto College in Addis Ababa.

The centre’s development plan has been finalised, and

methodologically speaking everything is in place. The cen-

tre is not yet operational however, and some of the people

we talked to expressed their impatience in this respect. In

total, five or six Centres of Competence are to be set up

throughout the country.

The difficulty of developing dual-type training and/or

apprenticeships

The TVET system currently includes a form of training

known as “apprenticeship”. It involves young people in

grades 10+1, 10+2 and 10+3, that is, young people taking

formal technical and vocational courses. It operates as fol-

lows:

� young people spend 70% of the school year, or 9

months, being trained at the centre;

� for the remaining 30% of the year, they are placed in

firms. The firms are usually identified and selected by

the training centre or college within its immediate eco-

nomic environment. They are generally small or medi-

um-sized enterprises forming part of the local economic

fabric.

In educational terms, work placements count for 22% of the

overall assessment for the year. A number of those we

spoke to told us that such placements are simply a form of

work experience. According to the head of the Education

Office in Addis Ababa, there are institutions that train busi-

ness executives to become genuine apprenticeship mas-

ters and thus to supervise young people on internships.

Some of those institutions (including the college we visited

in Dire Dawa) have stopped offering this type of training.

The field survey found that this type of apprenticeship

raised a number of problems in practice. Firstly, this is an

inappropriate description in that it refers to the experience

of working in a firm rather than a form of training alternating

between theory and practice: in this sense, the word “intern-

ship” would be far more appropriate than “apprenticeship”.

Secondly, no reference is made to any kind of contractual

relationship between employer and trainee, and the young

person continues to be regarded as a school pupil through-

out his or her time in the firm. Moreover, colleges have real

difficulty placing young people in firms and/or finding intern-

ships matching the technological and vocational content

covered by the school syllabus.

The reform of the TVET system includes the design and

implementation of co-operative training courses.40 In prac-

tice, the initial aim is to introduce a pilot dual training

scheme in partnership with major Ethiopian public and pri-

vate enterprises. The enterprises participating in the project

will select the young trainees according to the skills they

need. However, the plan is also for these enterprises to

take partial responsibility for training young people who

may be hired by enterprises not involved in the pilot phase

or who start their own businesses. The TVET centres par-

ticipating in the scheme will have to bring both their teach-

ing quality and technological investment into line with the

needs of enterprises.

The project currently being launched provides for the subse-

quent extension of the pilot scheme to MSEs and, in particu-

lar, production and service units in the informal sector and co-

operatives and training centres in rural areas. The document

says that this second phase is particularly important because

of the predominance of MSEs in the Ethiopian economy, the

current reform’s key requirement to open the TVET system to

a wide range of target groups, and the Government’s goal of

significantly increasing the number of people trained in the

vocational education and training system.

It is unlikely that successful co-operative training in large,

modern enterprises can be extended to the informal sector

as it stands. At present, the reform plan does not provide for

a significant investment in training for adult workers in

MSEs, let alone in training for the heads of such enterpris-

es to become “apprenticeship masters”, albeit only for

those young people under their responsibility within the tra-

ditional apprenticeship system. A comparison with the other

countries surveyed shows that such investment is the only

way to motivate professionals to take on young trainees

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 21

40 ECBP (August 2006), Co-operative Training and Enterprise Training.

and involve them in an effective learning process. Training

young people without giving adults already in work (many of

whom are under-educated) the means to upgrade their own

skills and thus to develop their careers engenders—as

craftworkers in Benin put it—a sense of fear among adults

vis-à-vis the growing influence of young people with greater

skills, which can but be detrimental to the smooth develop-

ment of on-the-job training.

3. Vocational training reform geared to the economic and social challenges

© AFD Working paper No 34 � Vocational Training in the Informal Sector - Report on the Ethiopia Field Survey 22

Figure 2. The phases of the reforms process

Source: Richard Walther.

3.2.3. The challenges of reform: moving from an

institutional to a grassroots approach

All the strategic and operational papers setting out and

organising the different phases and key points in the reform

process promise that the system will be opened up to those

currently excluded from it, and that efforts will be made to

involve its future beneficiaries. While target groups in the

informal sector are seen for their true worth, with an accu-

rate assessment of their situation, they are regarded as

potential individual beneficiaries rather than possible asso-

ciations set up to deal with economic, occupational or

industrial processes.

The various field surveys show that the institutional mind-

set of vocational training practitioners when it comes to

approaching people working in the informal sector is unlike-

ly to motivate the latter unless representative associations

are involved, be these territorial, vocational or sectoral or

simply NGOs. The field survey in Ethiopia was unable to

identify any highly structured organisations of informal

workers. However, steps are already being taken to form

groupings of stakeholders (which are mandatory in some

cases, particularly as a prerequisite for obtaining micro-

credit), networks of businesswomen, local, regional and

national agencies for MSEs, sectoral associations linked to

chambers of commerce and so on. A 2003 Ministry of Trade