Wage Rate Disparity in Antebellum America 1820-1860 The Market Economy’s Response to Industrialization Courtney A. Winther Austrian Student Scholars’ Conference Mises Institute November 3-4, 2006 Grove City College Pennsylvania

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Wage Rate Disparity in Antebellum America

1820-1860

The Market Economy’s Response to Industrialization

Courtney A. Winther

Austrian Student Scholars’ Conference

Mises Institute

November 3-4, 2006

Grove City College

Pennsylvania

1

The exchange of labor for commodities is a simple and natural phenomenon of an

unhampered market economy. Such a straight forward transaction has been a topic of

much scrutiny. The debate whether the division of labor exploits the worker continues to

be controversial yet there is little regard for the exploitation or the interests of the

capitalist. Of particular note is the switch in American emphasis toward manufacturing

and industrialization and, in turn, a focus away from rural agriculture. The period 1820-

1860 has been the attention of both economic and labor historians due to the apparent

disparity in wage rates between occupations as well as an apparent “lull” in the rise of

real wages. This observation made by many historians that “wages showed virtually no

growth from 1820-1860” (Vedder 2001, p. 81) is inconsistent with the patterns of data

available and basic economic theory of wage labor. A thorough understanding of both

the history of American industrialization and of the market economy indicates that the

unhampered economy is able to adapt to changing conditions in production without

exploiting workers in the process. To do so, this paper evaluates the relevant available

studies and data from this time and examines it in light of historical conditions and the

desires of the American worker. In conclusion, interpretations of changing economic

phenomenon are discussed.

Before the data is evaluated, it is important to understand why this era has been

scrutinized so heavily by labor historians in light of its relevance to America’s history.

First, the early nineteenth century provides us with the first era in Untied States history

without war. Prior to these years, America was either under the economic conditions

imposed by Britain, the drain and recovery of the Revolutionary War, or the War of 1812.

Thus, in some sense, this was the first time that the American economy could be

2

evaluated apart from “unnatural” economic restraints. In short, it was an experiment in

the workings of the unhampered labor market. Second, research during this era evaluates

the effect of the post-revolutionary depression and the rapid increases in economic wages

in the 1790s in light of the consequences that followed. In the years preceding 1790 there

was a general similarity of wage rates between occupations for comparable skills but this

disappears after 1790 (Adams 1968, p. 405). Third, there was a decline in wage rates in

1802-1803 and in 1807-1808 that reflect the period of the Peace of Amiens and the

Jeffersonian Embargo respectively that “substantially reduced United States income from

foreign trade and shipping” (Adams 1968, p. 405). In addition, the country did not fully

recover from the Panic of 1819 until the mid 1820’s. Other economic factors were

important including the panic of 1837, a secondary downturn in 1839, and the Panic of

1857 (Adams 1986, p 625). All of these aspects of American history relate either

immediately or consequentially to economic conditions and thus inconsistent wage trends

are often not consequences of industry differences but of historical or political factors.

With that said, economic theory continues to apply despite this and the situation is

reversed wherein economic conditions determine political and historical factors.

The other primary reason why this research is important is in the historical

geographic aspects. Not only does it allow historians to evaluate migration patterns and

the mobility of the labor market but it allows the evaluation of the “convergence of

geographically distinct labor markets” (Margo 1998, p. 51). As example, some have

argued that the South should have experienced a growing trend toward industrialization

much like what was seen in the North. Evaluating data provides the answer and shows

that there was “very little verification for a thesis of labor scarcity and high wages as

3

being the cause of technological change and urban-industrial development. (Earle and

Hoffman 1980, p. 1078)1

While many have researched the statistics available from this era, there are but a

few major studies that have been regarded as significant enough to remain the subject of

modern discussion. Perhaps the most famous was conducted by Jeffrey Williamson and

Peter Lindert (Lindert and Williamson 1980). This study uses several different records of

wages and standards of living from antebellum America with the conclusion that the

difference between non-agricultural wages “widened” between 1816 and 1856 (Linder

and Williamson 1982, p. 419). The result was that the gap between low or unskilled

labor and skilled artisans expanded creating wage disparity with no overall improvement

in the standard of living (Margo and Villaflor 1987, p. 883). Their conclusions are

primarily drawn from five wage series sources.2 Recent commentators have critiqued

their use of more obscure data while obtaining sometimes different conclusions and often

ignoring the more prominent and straightforward statistics compiled.

The second study that has recently become prominent was conducted by Robert

Margo (Margo 2000) and is a response to Williamson and Lindert. While Margo

examines and uses the same data, he also introduces two “new” sources of data that had

previously been overlooked in early nineteenth century labor history. The first comes

from the Reports of Persons and Articles Hired that exists as a compilation of payroll

1 This information is provided as part of Earle and Hoffman’s critique of H. J. Habakkuk’s argument for the

scarcity of American labor.

2 The methods of Williamson and Lindert’s study are examined in more detail in Scott D. Grosse’s On the

Alleged Antebellum Surge in Wage Differentials: A Critique of Williamson and Lindert. Five wage ratio

series are used in their study consisting of the Massachusetts carpenter/laborer series, earnings of public

school teachers, daily wages of laborers in Carroll Wright’s Massachusetts data, wage ratios from Philip

Coelho and James Shepherd, a ratio of earnings of artisans and laborers, Erie Canal payrolls, and wages of

civil engineers (Grosse 1982, p. 415-8).

4

records of civilian employees in the United States Army commissioned for either short or

long term employment. This report includes approximately 55,000 wage entries and has

the advantage of including all parts of the country in various occupations (Margo 1998, p.

52). While it is possible that United States Army wages may not be consistent with the

whole of the economy, Margo, as well as others, argues that these wages seem on par

with other data we have of laborers for the same year, occupation, and geographical

location (Margo 1987, p. 875, 877). One disadvantage to this data is the lack of

information in regions where there was an absence of United States Army forts. Further,

these forts did not always have need for civilian work in a consistent demand over a

number of years and thus data is not always continuous and does not account for years

when particular forts were not in operation. While the data is significant, it is not large

enough to account annual time series with much specificity (Margo 1998).

The second source of new data that Margo uses is the Census of Social Statistics

of 1850 and 1860. While it may seem that this research would only be helpful for the

years immediately before the War Between the States, the information that was gathered

in this Census included data from businesses on wage data from the early nineteenth

century. While extremely helpful, any firms that were no longer in existence when the

survey was conducted cannot be counted. Because non-pecuniary wages were often

given particularly in rural areas including board, mending, and other domestic services,

this survey distinguishes between wages with and without non-pecuniary benefits.

Margo also draws on the Weeks and Aldrich reports that were part of the 1880 census and

as part of the congressional inquiry into the effects of tariffs in the 1890s (Mitchell 1998,

p. 43). Based on existing as well as new data, Margo reaches a more optimistic

5

conclusion mostly contrary to Williamson and Lindert that real wages and the standard of

living, though varied throughout antebellum America, had an overall steady increase.

While Margo’s data appears to be credible and of greater quantity than that of former

studies, the difference stems primarily from the manner in which in which one interprets

it.

While many minor studies have been conducted, it is important to include the vast

amount of data collected and analyzed by Donald Adams. In particular, selections of his

research focus specifically on wage rates of this era but evaluate different geographical

regions in accordance with national economic trends. These include Philadelphia,

Maryland, Western Virginia, and the Brandywine region (Adams 1968, 1986, 1992, 1982

respectively). His research has been highly regarded by many labor historians and his

conclusions include that “American agricultural wages were comparable to those of

England and the wage differential between skilled and unskilled labor, though similar in

both countries was generally wider in the Untied States” (Earle & Hoffman 1980, p.

1058). While there are other studies that have been used historically, they are less

relevant or else have been included in the evaluation of other studies.3

The fundamental problem that is faced by the evidence of wage rates is the

limited quantity of data that allows it to be interpreted in many different ways. In order

to develop a complete picture for the economic inquirer, Donald Adams states that the

relevant information would include immigration, occupational distribution, employment

3 Of other studies conducted, of particular interest is Stanley Lebergott’s Manpower in Economic Growth

(Lebergott 1964) that provides a more chronological look at wage data in detail from 1800. The other

major study that is still referenced is the Paul David and Peter Solar report that relies heavily on the

mathematical aspects behind changes in wage rates during the nineteenth century. An aspect of this study

is used in this paper (David 1967).

6

statistics, cost of living, and the level or retail prices and wages (Adams 1968, p. 404).

Unfortunately, not all this data is available to the economic historian and because there

are so few sources that provide even a portion of this information, much as to be derived

through “capita income growth from movements in underlying components” (Margo

1998, p. 51). In addition, where account books and payroll records provide information

they often have a “lack of coverage of certain geographic regions, where surviving books

are scarce, and [have] the difficulty of valuing payment in kind” (Mitchell 1998, p. 43).

Thus, it is difficult to define the type of work being done in order to compare to other

regions or decades. Second to the general lack of data, is the lack of data accumulated at

the given time. Most research was conducted in retrospect and thus both the accuracy of

the information as well as the sample size and geographical locations are causes for

concern.

When evidence from this era is scrutinized, it is often found to be varied in its

results with no consistent pattern. Because of this, it is important that evidence is

evaluated in terms of historical events. The primary and most obvious historical factor is

the general rise in industrialization and the shift away from rural sustainability to urban

manufacturing. In general, this movement away from agriculture coincides with a growth

in per capita income (David 1967). H. J. Habakkuk, who has completed significant

studies on this era, believes that this increase in manufacturing is due to a shortage of

labor in a country that “contained a modest population and abundant land” thus

“entrepreneurs adopted new technologies to increase the productivity of labor.”

Believing that American labor was limited, he concluded that it was, therefore, high

priced (Earle and Hoffman 1980, p. 1055). A much more probable explanation of

7

industrialization, however, was that a move toward learning “how the shortage of skilled

labor could be overcome by the combination of machines and unskilled labor” thus to

“convert cheap unskilled labor into cheap skilled labor” (Earle and Hoffman 1980, p.

1055). This is found most obviously in the agricultural sector. Because approximately

sixty percent of the American populace was employed in the rural market, (Adams 1986,

p. 635), changes in agriculture production, whether they were an increase in productivity

or higher incentives to work in the urban market, had significant influence on the

economy as a whole.

Second, immigration played a vital role in wage data. Consistent with traditional

economic thought, higher wage rates usually existed when immigration was at a low.

When evaluating the existing data in light of immigration trends, Robert Margo finds that

“it is not surprising that real wages, especially of the unskilled stagnated during the

1850’s” (Margo 1998, p. 53) because of the “shock” of mass immigration. This had a

strong impact on the differential between urban and rural wage markets. Because

immigrants were looking to build savings and investment, most placed a stronger

emphasis on year-round employment that could be found in cities. Agricultural labor was

often less than twelve months a year and the living atmosphere required more self-

sustainability including the building of a home, growing of food, and other knowledge of

the land. The result of this was that it “had the effect of depressing the cost of urban

labor,” but despite this depressed cost, “it did not reduce it to the level where rural

employment became viable or attractive” (Earle and Hoffman 1980, p. 1064). Thus

while the countryside lost its attractiveness to newcomers so it was at the same time

losing its appeal to native born Americans.

8

Third, poor relief and early forms of welfare made its debut during this time and

influenced the labor market and labor wages. The main impact of this was felt in the

1850’s when welfare “exploded.” As more workers became dependent on a consistent

year-round wage they also became accustomed to more consistent spending. When wage

prices fell, workers of lower wages became vulnerable. When the costs of basic

necessities rose relative to wages, a “substantial increase in the demand for public

assistance” arose and the “increase in relief was less than the increase in the demand for

relief” (Margo 1998, p. 54). Artificial stimulation of market conditions clearly impacts

and distorts wage data for certain periods especially when relief for the poor varied

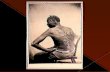

throughout the 1850’s. Finally, another distortion of wage data was slavery. While most

of industrialization occurred in the North, the South experienced the impact of

industrialization as it transcends markets. Slave labor, though it was low skilled labor,

had the impact of displacing low skilled non-slaves from certain markets and inevitably

effected wage data in the South and likely in northern regions as well.4 With perspectives

on the studies that have been done and some of the historical factors that surround this

era, the actual data can be presented and evaluated according to this changing shift in

American industry.

I

When Williamson and Lindert presented their findings, they concluded that

income inequality rose from 1820-1860 such that there was a larger and more significant

gap between the agricultural or factory worker (low or unskilled) and artisans (skilled).

4 Economic historians also point out that the California gold rush had a significant impact on the population

in given markets. This population shift may be another reason why wage data does not appear to rise

steadily.

9

As an explanation for this they said that the structure of pay changed in such a way that

“the price of capital goods fell” thus increasing the purchasing power of capital. Because

capital and skills were complementary factors, “the demand for skilled labor increased

relative to the demand for unskilled labor” (Margo and Villaflor 1987, p. 883). Thus they

suspect that the result was a large differential between the skilled and unskilled wages.

This is the basis of their argument for income inequality. Reviewers, however, have

found that these two scholars have apparently “selectively chose from among the

available published data so as to present a picture widely at variance with the majority of

previously published wage series” (Grosse 1982, p. 413). Scott Grosse goes on to say

that there appears to be a link to Jeffry Zahler’s study that has peculiar conclusions such

as skilled workers earning more than artisans including carpenters, millers, and smiths

(Grosse 1982, p. 414). It is difficult to determine whether it was from this data that they

deduced the income inequality gaps.

Perhaps more important that the pure data is the motive for the action that caused

the shift. There are several reasons why people moved from sustainable agricultural

production to industrialization. First, there was a greater difference in the labor options

available between urban and rural environments. Markets in rural areas had few

employment options but were also separated from a competitive market with other non-

agricultural production. Since there was no emergence of new agricultural land or

produce, wage rates remained about the same. While prices and wages in urban areas did

have some arbitrage effect, this influence was slow due to primarily distance between the

markets and the limited number of people engaged in both markets. The city

10

environment, by contrast, gave workers greater wage opportunities particularly during the

antebellum era.

When Donald Adams conducted his study on wage rates in Philadelphia, he

concluded that “a wider variety of jobs were available and a large number of employment

opportunities presented themselves to the worker in 1830 than in 1790” (Adams 1968, p.

417). In contrast to the city, he notes that for the economy as a whole “the alternatives

open to agricultural workers were limited” (Adams 1986, p. 637). While opportunities

were limited for those in agricultural arenas, this did not limit many from moving to the

more ample market. There were enough opportunities that made this change aid in the

shift of the American market into factory industrialization. In short, there was enough

attraction of alternative employment in cities such that when “urban employment

presented itself, workers responded” (Adams 1986, p. 638). Besides the broad category of

more options, specific factors motivated laborers to move to urban environments. These

included, among others, the rising wages or at least higher wages compared to rural

agriculture, better working conditions, higher standard of living, and greater job security.

Long term job security proved to be an important point for workers’ desire to seek

urban wages. Agricultural labor had perks that often included non-pecuniary wages such

as housing and board as well as domestic services including washing, mending, and

provision and preparation of food. The primary disadvantage was the relatively low

wages. This was often because wages included goods or services in kind as well as a

lower monetary yearly income. Generally, those who worked in agriculture could only

expect work for one-third to one-half of the year. The percentage was higher in the South

that could usually provide agricultural labor between eight and twelve months out of the

11

year (Earle and Hoffman, 1980, p. 1056). The North had less crop variance with which

to provide the security of year round employment. Even if wages were sufficient to the

desires of the worker on a monthly basis, there were between two and four months of

unemployment. Agricultural workers were hired usually by the month or by the day.

Data indicate that workers employed by the month generally had lower wages relative to

those hired by the day (Margo and Villaflor 1987, pp. 878-9). Historians have accepted

this difference as being due to higher demand given at certain times that required

additional day laborers. There also seems to be reason to believe that monthly laborers

were willing to accept a lower daily wage in exchange for stronger job security (Adams

1986, p. 632). The fluctuations in demand for labor due to the seasonal nature of

agriculture created periods of time in that employment was extremely scarce and other

times in the same year when the situation was reversed and labor was scarce. Even as

industrialization flourished, merchants and non-farm laborers would still engage in

agricultural employment during harvest time. Such a practice is evidenced by Frederick

Law Olmstead who said that “in harvest time, most the rural mechanics closed their

shops and hired out to the farmers at a dollar a day” (Earle and Hoffman 1980, p. 1060)

indicating that during certain times of the year, artisans often found it more valuable

monetarily or otherwise to work in the fields. For most agricultural environments

though, the few months when agricultural work was not available were “glutted with

underemployed laborers and few buyers” (Earle 1980, p. 1062).

All this goes to illustrate that for many workers there was a desire to make a better

life for themselves in the city. Economic and labor historians have created formulas to

estimate the wage that a capitalist of industrialization or employer would have to offer in

12

order to meet the demands of the profitability of his business. In general, an agricultural

worker would have to know that he would benefit from relocating to the city. This

enticement was usually in the form of a wage that was higher than his existing wage in

addition to his estimated cost of replacement of goods in kind as well as a general

compensation for urban living. As rural living was still preferred, wages had to be

adequate enough to be of higher value than the estimated subjective value of country

living.5 From a conceptual perspective, because rural wages were already low and

inconsistent, “these workers could be induced into urban employment easily and

inexpensively.” Thus, we see a rapid shift to industrialization in the North while the

South, because of more sustainable agriculture and a longer work year, found that the

“costs of attracting rural labor to city jobs also increased substantially” (Earle and

Hoffman, 1980, p. 1056) because of higher agricultural incomes. The question is

whether this easy inducement of labor particularly in the North is a sign of exploitation of

workers merely because they created an extensive source of cheap labor or because of

desire on the part of the workers.

Despite a general preference for an agrarian lifestyle, given an equal monetary

wage, people moved to the cities and engaged in manufacturing. Thus, when labor

historians evaluate whether industrial workers received a fair wage they often look at the

poor conditions of city living and conclude that workers were exploited by capitalists

who offered enough of a wage to entice them but not what was due them and so took

advantage of unskilled cheap labor. Several points can be made here. First, is merely the

fact that workers did move in this direction thus indicating a general willingness to give

5 Information on the wage differential equations between urban and rural employment can be found in the

mathematical equations combined with historical data of Earle and Hoffman 1980.

13

up one opportunity for another. Had this been a matter of coercion, the evaluation of this

would be through completely different means. As labor was free and voluntary, it

becomes a matter of the acting out of individual preferences in the market.

Second, the unemployment rate was low during the early nineteenth century. This

indicates that jobs were adequate to meet the needs of workers. If non-industrialized jobs

had been few and the only choice was for low-wage labor in factories, one possibly could

argue that workers were “exploited” but even then it would not be by capitalists but by

the limited opportunities of the market – namely the lack of new enterprise and

entrepreneurship. As it was, unemployment was only between one and three percent

(Adams 1968, p. 416). As Ludwig von Mises states, “unemployment in the unhampered

market is always voluntary” (Mises 1996, p. 599) indicating that those who labored and

those who did not, valued that choice above their other options. Thus most were satisfied

with labor opportunities and wages.

Third, laborers found a greater standard of living with this shift to

industrialization. This happened in two ways. First, those in industrialized occupations

found higher wages and standards of living. Donald Adams finds strong support that

“rising wages and earnings contributed to an increase in the industrial workers’ material

well-being” and finds that “manufacturing wages were, on average, 14 percent greater

than farm wages” (Adams 1982, 906, 910). Second, this higher standard of living was

extended to those who were somehow, directly or indirectly, connected to manufacturing

and thus “changes in the very structure of the labor force helped spread this improvement

to workers as a whole” (Adams, 1982, p. 906). A particular example of this spread in

well-being was found in the Brandywine region. In a report evaluating the particular data

14

of the area, Adams concludes that “the picture that emerges from our data is hardly one

of increasing exploitation or dire poverty. Indeed, it appears that workers in the

Brandywine region shared generously in processes of economic growth and development

in the antebellum years” (Adams, 1982, p. 915). Thus, from the standpoint of individual

workers, it is difficult to find reasons why workers themselves would choose to be

exploited by this labor shift. While some have argued that spatial and geographic factors

limited the ability of the market to arbitrage the difference, Margo concludes from wage

census data that the shifts and changes in income are “consistent with a process of spatial

arbitrage” (Margo 1998, p. 54). It appears that most, if not all, industries were influenced

by increased wages through industrialization.

Though the exploitation of women and children in the factory and sweat-shop

environment has often been expounded upon by labor historians, it is worth mentioning

that women voluntarily sought industrial employment as well. While it appears to be a

legitimate point that women had less choice between working in the urban or rural market

as they were often bound by the locations of a husband or family, women sought this new

wave of employment even when domestic labor was available. Generally, the wage

difference between these two industries (factory and domestic) was nil as wage rates

were comparable or equal. Thus those in the city were attracted to this industry possibly

because there were “opportunities presented by overtime earnings, the availability of

piecework, or…the social stigma attached to domestic service in America” (Adams 1982,

p. 912).

15

Finally, even if one were to assume that exploitation could exist on the market, or

that wages were less than fair in industrial markets, it must be made clear that this could

not have lasted long. Earle and Hoffman explain this point well:

In the long run, it should be noted that exploitation diminished. It did so

precisely because, as new firms entered the market to take advantage of

low-cost labor, they eventually created a competitive year-round labor

market with numerous firms competing for idled rural labor. Or,

expressed differently, the level of exploitation dwindled as urban labor

markets themselves became perfectly competitive (Earle and Hoffman

1980, p. 1063).

Thus once again, the process of arbitrage occurs as capitalists make use of a low cost

labor market and thus create competition between low cost industrial labor markets.

However, this process is continuous and well never be “perfectly competitive” though we

find the balance of wages as the industry headed toward and strove toward an

equilibrium.

II.

Perhaps of more concern to labor historians is the apparent disagreement between

the wage increase of unskilled or low skilled workers to that of artisans and specialized

craftsmen. Certain data gathered by Williamson and Lindert as well as that gathered by

Jeffry Zahler (Zahler 1972) indicate that the wage rates of artisans remained low during

this industrialization and that this interest in the mechanization of processes hurt and

exploited workers who deserved higher wages. From an economic standpoint, if this

were true, than artisans were not able to meet the changing demands of consumers or did

not anticipate the consumers’ acceptance of mechanized production. Blaming capitalists

for ingenuity and entrepreneurship would have only delayed or hindered the growing

demands of the market economy. In actuality, however, data does not seem to confirm

16

that artisans were hindered in wages. There are two (possibly contrary) positions that are

taken on this matter by this school of thought. The first states that the level of wage

inequality increased during this era indicating that either unskilled workers obtained

lower wages or that skilled laborers obtained higher wages or both. The second position

states that while unskilled labor wages increased, the wages of artisans remained about

the same or increased only insignificantly. As illustrated above the former seems

unlikely as low skilled wages did increase and higher standards of living were achieved

during this era. The question is then a matter of whether skilled labor extremely

exceeded the increase rate of low skilled labor or whether it stalled. Neither seems likely.

When Grosse evaluated this data, though he presented none of his own, he found

Williamson and Lindert’s conclusion to be irretrievable from their given data. The data

that the latter relied on appeared to be from Zahler’s study that does not provide a

complete picture.6 Margo and Villaflor, evaluating this data as well as additional

information, conclude that there is “no evidence of a widening of the antebellum pay

structure in any part of the country, and therefore no evidence that income inequality

increased before the Civil war” (Margo and Villaflor 1987, p. 892). Further, it appears

that wages for all skill levels increased at a steady and rather consistent rate. Thus

Margo, in a critique of Williamson and Lindert emphasizes that “the rates of [long-run]

growth are mostly positive but (in the case of common labor and artisans) are generally

lower than rates observed during the 20th century” and thus seems reasonable. He goes

on to mention “that the growth rates for artisans do not exceed growth rates for common

labor. This is inconsistent with previous claims that a ‘surge’ in the skilled-wage

6 The debate between Williamson and Lindert and Grosse can be found in The Journal of Economic History

volume 42. Adams also contributes to this discussion in his own article.

17

premium occurred before the Civil War” (Margo 1998, p. 53) giving specific critique to

the claims of Williamson and Lindert.

It is important that one does not confuse the wage and price variance of the

antebellum era with the overall economic performance of the market. As noted above,

there were various factors that make this wage data appear inconsistent and may give rise

to odd conclusions. Stanley Lebergott in his important study Manpower in Economic

Growth makes the essential observation that “in a dynamic economy relatively short-term

changes in production and demand forces can readily overlay any longer tendency toward

equalization of factor returns” (Aldrich 1971, p. 418). Whether this equalization is

possible is another discussion but does make the point that short term changes in a

society can appear to distort the big picture data that we derive to determine the economic

success of an era in history.7 Because the states experienced a slow wage growth from

approximately 1820-1839, a significant wage growth in the 1840, and then a stagnation in

the 1850s (Margo 1998, p. 53), with a major business cycle from 1835-1845 (Aldrich

1971, p. 413-5) data evaluated without light of these historic and economic events in

terms of the boom and bust cycle can be misinterpreted to indicate that workers gained

more or less by labor and wage prices. Another thing to keep in mind is that the

difference between unskilled and skilled labor relative to each other changes with times

of general economic prosperity or decline. In general, unskilled labor will gain on skilled

labor during eras of prosperity while this trend is reversed in times of distress (Adams

1968, p. 412).

7 Vedder in his book review of Margo states that data can often be deceptive of the state of an economy and

questions whether current economic data in America might lead one in the future to believe that economic

conditions were not optimal and that certain industries might have exploited workers.

18

Based on this data, there are obviously different perspectives based on

interpretations. Perhaps the best way to categorize them is in terms labeled by Margo as

the optimist and pessimist. The former holds that labor markets have difficulty coping

with changes and thus wages lagged behind when prices rose, thus creating declines in

real wages. The latter position holds that market-like processes are able to respond to

changing economic ideas and thus changes to economic progress. The method in which

this data is interpreted is dependent upon the perspective of the user. Looking through

the research and analysis presented by various interests in economic and labor history, it

seems clear that markets were able to adjust as workers responded to changing desires.

The historian might look back and compare the work conditions of the nineteenth century

to today’s version of industrialization and conclude that work is better today than in

antebellum times. Yet for the workers formerly engaged in manufacturing, they

compared it with their previous way of life on the farm and concluded that their life and

their work was better than it was in former times. From both the perspective of the

interest of the worker and the analysis of economic theory, the myth that workers were

exploited and that wages did not improve must be dismissed. The simple concept of the

labor market continues to exist today but the process of exchange must not become

complicated by the belief that others know what is best for the individual.

19

References

Adams, Donald R. Jr. 1968. “Wage Rates in the Early National Period: Philadelphia,

1785-1830.” The Journal of Economic History 28, no. 3 (September): 404-26.

________. 1982. “The Standard of Living During American Industrialization: Evidence

from the Brandywine Region, 1800-1860” The Journal of Economic History 42, no. 4

(December): 903-17.

________. 1986. “Prices and wages in Maryland, 1750-1850.” The Journal of Economic

History 46, no. 3 (September): 625-45.

________. 1992. “Prices and Wages in Antebellum America: The West Virginia

Experience.” The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 1 (March): 206-16.

Aldrich, Mark. 1971. “Earnings of American Civil Engineers 1820-1859.” The Journal of

Economic History 31, no. 2 (June): 407-19.

David, Paul A. 1967. “The Growth of Real Product in the United States Before 1840:

New Evidence, Controlled Conjectures.” The Journal of Economic History 27, no. 2

(June): 151-97.

Dulles, Foster Rhea. 1955. Labor in America: A History. New York: Thomas Y.

Crowell.

Earle, Carville and Ronald Hoffman. 1980. “The Foundation of the Modern Economy:

Agriculture and the Costs of Labor in the United States and England, 1800-60.”

American Historical Review 85, no. 5 (December): 1055-94.

Foner, Philip S. 1947. History of the Labor Movement in the United States v. 1. New

York: International Publishers.

Grosse, Scott D. 1982. “On the Alleged Antebellum Surge in Wage Differentials: A

Critique of Williamson and Lindert.” The Journal of Economic History 42, no. 2:

413-8.

Lapides, Kenneth. 1998. Marx’s Wage Theory in Historical Perspective. Westport,

Connecticut: Praeger.

Lebergott, Stanley. 1964. Manpower in Economic Growth; The American Record since

1800. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lindert, Peter H. and Jeffrey G. Williamson. 1982. “Antebellum Wage Widening Once

Again.” The Journal of Economic History 42, no. 2 (June): 419-22.

20

Margo, Robert A. and Georgia C. Villaflor. 1987. “The Growth of Wages in Antebellum

America: New Evidence.” The Journal of Economic History 47, no. 4 (December):

873-95.

Margo, Robert A. 1998. “Wages and Labor Markets before the Civil War.” The American

Economic Review 88, no. 2 (May): 51-6.

________. 2000. Wages & Labor Markets in the United States, 1820-1860. Chicago:

University of Chicago.

________. 2006. “Wages and Wage Inequality” in Historical Statistics of the United

States: Millennial Edition. Vol. 2: Work and Welfare. New York: Cambridge.

P. 40-6, 254-6.

Mises, Ludwig von. 1962. Planning for Freedom. South Holland, Illinois: Libertarian

Press.

________. 1996. Human Action. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Mitchell, B. R. 1998. International Historical Statistics: The Americans 1750-1993. 4th

ed. London: Macmillan Reference.

Rosenberg, Nathan. 1967. “Anglo-American Wage Difference in the 1820’s.” The

Journal of Economic History 27, no. 2 (June): 221-9.

Vedder, Richard. 2001. Review of Wages and Labor Markets in the United States, 1820-

1860. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 4, no. 1 (Spring): 81-3.

Williamson, Jeffrey G. and Peter H. Lindert. 1980. American Inequality: A

Macroeconomic History. New York: Academic Press.

Zahler, Jeffry F. 1972. “Further Evidence on American Wage Differentials, 1800-1830.”

Explorations in Economic History 10, no. 1 (Fall/Autumn): 109-17.

Related Documents

![ANTEBELLUM AMERICA Sectionalism & Reform. “Before the [Civil] War” 1820 - 1860 Missouri CompromiseCivil War ANTEBELLUM.](https://static.cupdf.com/doc/110x72/56649cfe5503460f949cf155/antebellum-america-sectionalism-reform-before-the-civil-war-1820.jpg)