French Beads in France and Northeastern North America during the Sixteenth Century Author(s): Laurier Turgeon Reviewed work(s): Source: Historical Archaeology, Vol. 35, No. 4 (2001), pp. 58-59, 61-82 Published by: Society for Historical Archaeology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616952 . Accessed: 31/12/2012 17:10 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. . Society for Historical Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Historical Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Turgeon FrenchBeads 2001

Nov 16, 2015

Turgeon FrenchBeads 2001

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

-

French Beads in France and Northeastern North America during the Sixteenth CenturyAuthor(s): Laurier TurgeonReviewed work(s):Source: Historical Archaeology, Vol. 35, No. 4 (2001), pp. 58-59, 61-82Published by: Society for Historical ArchaeologyStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616952 .Accessed: 31/12/2012 17:10

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Society for Historical Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toHistorical Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sochistarchhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/25616952?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

58

Laurier Turgeon

French Beads in France and Northeastern North America

During the Sixteenth Century ABSTRACT

Although it is generally recognized that the French played an

important role in the bead trade during the early contact period in Northeastern North America, there have been no serious

attempts to carry out archival research and to locate reference

collections of beads in France; consequently, surprisingly little is known about French beads. North American bead

researchers are still asking some very basic questions about

the provenience, chronology, and trade of French glass beads.

This study seeks to answer these questions by drawing on a combination of written sources and archaeological

collections?early French travel literature and collections of

beads from First Nations contact sites. Information from

these relatively well-known sources is supplemented with new

data gathered from post-mortem inventories of Parisian bead

makers and from notarized contracts containing descriptions of

beads purchased for the North American trade. The study also

draws on a unique collection of beads dating from the second

half of the 16th century, recently unearthed in the Jardins du

Caroussel, near the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Introduction

Beads have been the object of much scholarly investigation by archaeologists, ethnohistorians, and colonial historians of the eastern United States and Canada because of the prominent role they played in the early history of contact between Aboriginal peoples and Europeans in North America. Archaeologists have excavated, inventoried, and studied collections of beads from hundreds of contact sites in the Northeast. Elaborate classification systems of glass and shell beads have been developed, based on method of

manufacture, shape, size, and color (Kidd 1970; Ceci 1989). Since the assemblages of beads

change rather quickly over time, they have

been seriated and used for establishing chronolo

gies of sites as well as reconstituting trading networks (Kenyon and Kenyon 1983; Bradley 1983; Rumrill 1991; Moreau 1994; Fitzgerald,

Knight, and Bain 1995). Scholars have begun to use these findings to study the social and

cultural meanings beads had for Amerindians and how they were integrated into their thought worlds (Hamell 1983, 1992, 1996; Trigger 1985, 1991; Miller and Hamell 1986).

It is generally recognized that the French were

very active in the North American bead trade from the 16th century on. Many scholars of bead research have even suggested that the large majority of glass beads found on contact sites of the Northeast were traded by the French

(Kidd 1979; Bradley 1983; Kenyon and Kenyon 1983; Smith 1983). References and sometimes

descriptions of trade beads occur in the travel accounts of French explorers and missionaries such as those of Giovanni da Verrazzano, Jacques Cartier, Marc Lescarbot, Samuel de Champlain, Gabriel Sagard (1632, 1866), and Paul Le Jeune.

Early French colonial sites like St. Croix Island

(Bradley 1983), Quebec City (Clermont, Chapde laine, and Guimont 1992), Montreal (Desjardins and Duguay 1992), and Sainte-Marie-Among the-Huron (Kidd 1949) have provided invaluable collections of glass beads from which to refer ence those found on contact sites.

Yet surprisingly little is known about French

beads, given their important role in the early his

tory of North America. Unlike Dutch beads, for which entire assemblages have been unearthed and studied in Holland as well as North America

(Karklins 1974, 1983; Huey 1983; Kenyon and

Fitzgerald 1986; Baart 1988; Lenig 1996), there have been no serious attempts to carry out

archival research and to locate reference collec tions of beads in France. Furthermore, because French colonial sites were only established in the 17th century and most of the French travel literature is also from the 17th century, the 16th

century remains in a sort of limbo. Little is known about the trade of the French fishermen and the Basque whalers who began plying the

waters of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence in ever

greater numbers during the first half of the 16th

century (Turgeon 1998:590). There has also

been a tendency to concentrate on glass beads

and to not pay much attention to beads made of other materials such as enamel/faience (frit-core), shell, jet, bone, and coral. North American bead researchers are still asking some very basic

questions about the provenience, chronology,

Historical Archaeology, 2001, 35(4):58?82. Permission to reprint required.

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

a b c d e

e O f g h i j k I

m n o

P Q r

8 t U V W

$ o # x y z aa bb

cc afd ee Pflf

/?/) // if kk II

^SlP 5 t 15 t 23 i t < 50 mm

mm nn oo

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 61

TABLE 1

DESCRIPTIONS OF BEADS FROM THE JARDINS DU CARROUSEL COLLECTION

Fig. Color, Shape (Size) KiddCode n

Glass Beads a Turquoise round glass, "robins egg," one broken (6 mm dia., 5mm long) IIa40 5

b Apple green round glass (color altered) (5.2mm dia., 6.4 mm long) 11a 24* 1 c Bright blue round glass (5mm diameter, 7 mm long) Ila48 or Ila55 1

d Blue round glass, color altered (5.8mm dia., 5.9 mm long) Ila48, Ila50 or Ila55 4 e Translucent round w/white stripes, "Gooseberry" (7 mm dia., 7.5 mm long) lib 18 3

/ Translucent oval w/white stripes, "Gooseberry" (6 mm dia., 11 mm long) lib 19 4

g Blue oval glass w/two white stripes (7 mm in dia., 8 mm long) lib 67 or IIb73 1

h White oval glass (5.5mm diameter, 9 mm long) Hal5 2

i Bright navy round glass seed (3 mm diameter, 3 mm long) IIa55 4

j Bright navy circular glass seed (1.9 mm diameter, 1 mm long) IIa53 or IIa56 4

k Black circular glass seed (2.1 mm diameter, 1.5 mm long) IIa7 4 / Opaque white circular glass seed (3 mm diameter, 2.1 mm long) IIal2 1

m Bright blue tubular glass (2.5 mm diameter, 15 mm long) la 19 1 n Black tubular glass (4mm diameter, 47 mm long) Ia2 1 o Translucent green tubular glass (2.9 dia., 35 mm long) Ial2 1

p Ultramarine faceted glass (6 by 3 = 18 faces) (6 mm in dia., 8 mm long) IIIf2 1

q Dark blue and white seed beads fired on glass paste (7x7 mm) IIa51/IIal 3 1 r Black, blue & white seed beads fired on glass (broken) (10 mm dia., 24 mm long) 2

Frit-core (Enamel/Faience) Beads

s Blue oval frit-core or enamel/faience w/ white appliques (9.9 mm dia., 11.7 mm long) 1 t Whitish round frit-core or enamel/faience, glaze removed (7 mm dia., 7.3 mm long) 1

Shell Beads u White discoidal shell (8-10mm in diameter, 1-2 mm long, line hole 2 mm dia.) 5 v White discoidal (small) shell (4.5mm diameter, 2 mm long) 1 w White natural shell (marginella) (6mm diameter, 10 mm long) 1

Jet Beads x Black discoidal jet (12mm diameter, 5 mm long) 1

y Black discoidal jet (7mm diameter, 2 mm long) 1 z Black faceted jet, 7 by 3=21 faces (7x7 mm) 1 aa Black faceted jet (12 mm in diameter, 14 mm in long) 1 bb Black melon jet (8.5 mm diameter, 7 mm long) 2 cc Black melon jet (22 mm diameter, 17 mm long) 1 dd Black glandular jet ( 12 mm diameter, 14 mm in long) 1

Amber Beads ee Reddish orange round amber (8 mm diameter, 6 mm long, broken at end) 1

ff Reddish orange round amber (6.5 mm diameter, 5 mm long) 13

gg Reddish orange faceted amber (5 by 3=15 faces) (9 mm dia., 7 mm long) 1 hh Reddish orange faceted (gadrooned) amber (11.2 mm dia., 7.2 mm long) 1

Rock Crystal Beads ii Translucent faceted rock crystal (8.4 mm diameter, 12.1 mm long) 2

jj Translucent faceted rock crystal (9.8 diameter, 15.5 mm long) 1

Bone Beads

kk Red (dyed) round polished bone (7.3 mm diameter, 7 mm long) 30 // Beige round polished bone (4 mm diameter, 3.1 mm long) 1

Coral Beads

mm Reddish orange round coral (8 mm diameter, 6.9 mm long) nn Reddish orange round coral seed (3 mm diameter, 2.5 mm long) 1 oo Reddish orange tubular (broken) coral (3.5 diameter, 5.5 long) 1

* The color of bead b has been altered, thus it could be a turquoise round glass (IIa40).

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

62 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 35(4)

and trade of French glass beads. Were beads manufactured in France? How do the French

assemblages compare with the assemblages found on colonial and Amerindian sites? Was the North American trade selective? When did it

develop? Answers to these questions will be sought by

focusing on a combination of archaeological and archival sources from the second half of the 16th century. The two sets of sources proved to be complementary?the archaeological record

supplied an interesting sample of beads while the archival documents furnished invaluable data on manufacturing techniques and trading networks. A collection of beads was located from the second half of the 16th century recently recovered from the Jardins du Carrousel in Paris. The site was excavated as part of a

salvage archaeology project at the Louvre, one

of the official palaces of the French monarchy in the 16th century and now the French national

museum, when it was being renovated and

expanded in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Since other collections of beads could not be

located, a search was undertaken in the notarial records of Paris and some of the port cities involved in the early Canadian trade: Rouen, La

Rochelle, and Bordeaux. The Parisian notarial records provided post-mortem inventories of bead

makers. These inventories were drawn up by

notaries after a person's death, at the request of the inheritors, and they contain detailed lists of the deceased person's material possessions: land,

buildings, furniture, tools, merchandise, clothing, and other personal belongings, including bills and accounts in the case of artisans, merchants, or shopkeepers. The post-mortem inventories of bead makers provide lists of beads (often with an indication of material, color, shape, and size),

descriptions of the tools used in the manufactur

ing process, and sometimes copies of unpaid bills giving names and places of residence of

clients. Records of purchases of beads and other

trade goods by ship's captains and outfitters were found in the notarized contracts of the

port cities. It appeared more promising to study reference

collections in France and undertake archival

research on bead makers and traders than to

attempt to refine bead chronologies from the

analysis of elemental differences in beads. In recent years, there has been a tendency to carry

out elaborate trace element analysis of beads and to explain differences by chronological phenomenon. Although helpful, this method has limitations. Recent studies have shown that other factors must be taken into account, such as differences in regional European manu

facturing recipes (Fitzgerald, Knight, and Bain

1995:133-134). Elemental composition of beads could vary, from one production center to

another, and sometimes even within the same

production center, depending on the provenience of raw materials and on the glass manufacturer's uses of vitrifying and fluxing agents (Trivellato 2001). For example, the elemental composition of the sodium carbonate, used as a fluxing agent, changed depending on whether it was

made from potassium (saltpeter) or the ashes of various plants and trees?sea-weed imported from either Syria, Egypt, or Spain; musk ivy or

ferns usually of a regional provenience; or again local trees such as oak, beech, or pine (Agricola 1912:585; Trivellato 2001).

The Jardins du Carrousel Collection

The beads from the Jardins du Carrousel were recovered from ditches used to dispose of human waste. Located just west of the

Louvre, the ditches appear to have been dug to extract the sand needed in the construction of the Tuileries Palace during the second half of the 16th century, when it became part of the Louvre complex (Van Ossel 1991:356). The construction of the Tuileries Palace was begun in 1564 during the reign of Catherine de Medici.

The project was abandoned in 1572 after the death of the main architect, Philibert Delorme, and taken up again and completed by Henri IV

(1589-1610). Varying in depth from 2 to 4 m

(6V2 to 13 ft.) and covering an area of some

50 to 70 m (160 to 230 ft.), the ditches were

progressively back filled with garbage collected

seemingly from the Louvre and the surrounding

neighborhoods of this central part of Paris. The

waste was occasionally covered with limestone and plaster, probably in an attempt to control the smell of the decomposing organic materials.

During the excavations, survey trenches were

dug in three different areas in order to better understand the structure and contents of the

ditches. Water screening with 0.5 and 2.5 mm

(0.2 and 1.0 in.) mesh screens was undertaken

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 63

in two of the trenches; it is in these areas that most of the beads and other small artifacts were

found (Van Ossel 1991:351-352). The large majority of identifiable materials

was bone (90%-95% of the collection): sheep, beef, and pig bones especially, with some rabbit, hare, and wild boar, and even a few human

bones. The remaining artifact assemblage was

comprised of ceramics, glassware, coins, pins, needles, draper's seals, and beads. Most of the ceramics and glass fragments were Parisian

types datable to the second half of the 16th

century. The variety and the quality of the ceramic and glass vessels suggests users from an upper social milieu. The stratigraphy could not be determined because the deposit had been

continuously stirred, mixed, and leveled. The

artifact chronology points towards a deposition spread out over time. The 213 coins recovered

helped narrow down the chronology?some coins had the year of manufacture stamped on them, which ranged from 1581 to 1599; those bearing only effigies were given approximate dates run

ning from 1572 to 1603. From this information, Paul Van Ossel has hypothesized 1590 to 1605 as the period of formation of the deposit (Van Ossel 1991:354). The collection is presently preserved at the Direction regionale des affaires culturelles de Vile de France, Service regionale d'archeologie, in Saint Denis, a northern suburb of Paris.

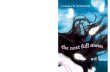

A total of 110 beads representing 41 different varieties were recovered from the site (Table 1, Figure 1). One of the striking features of the collection is the wide variety of materials, shapes, and sizes of the beads. They are made of eight different materials: glass predominates (44%), followed by jet (14%), shell (10%), amber (10%), coral (7%), frit-core (5%), bone

(5%), and rock crystal (5%). The beads come in an equally large number of shapes: round

(spherical), faceted, discoidal, oval (ovoid), tubular, circular (torus or doughnut), melon, and glandular, in that order. Sizes vary from the large black jet beads, measuring 22 x 17

mm, to the very small bright blue and black circular glass seed beads, 2 x 1-1.5 mm. On the other hand, the color spectrum of the beads is restricted to black, blue, turquoise, green,

white, and red. Furthermore, almost all of the beads are monochrome; only three glass beads and one frit-core bead are polychrome.

Although the collection is comprised of an

interesting assortment of beads, it is small and does have limitations. Given the size of the

sample, there are an exceptionally large number of bead varieties. Most of the beads (65%) exist as single examples; rarely are there more than four examples of the same variety. This is not

due to negligence, nor to a selective procedure implemented at the time of the excavation. The archaeologists who worked on the project have assured me that all of the beads recovered were inventoried; none was discarded (Fabienne Ravoire, pers. comm.). Only two varieties were

recovered in fairly large numbers: the round amber beads (13 examples) and the round red bone beads (30 examples), probably the remains of necklaces or rosaries. Generally, the same

bead varieties were not associated with one

another; they were recovered in different trenches and ditches. For example, only two of the seven

shell beads were found together. The diversity of the assemblage and scattered distribution of the beads, as is the case with the other artifacts, indicates that they came from numerous places and were deposited at different times. It appears, then, that the sample is fairly representative of the varieties of beads worn by Parisians at the time. Some beads still had wire or thread attached to them, suggesting they were used as ornamentation on clothing, which helps to

explain why so many beads were found as single examples. If one can rely on the ceramics and coins as chronological and social markers, there is every reason to believe that these types of beads would have been worn by well-to-do Parisians during the last quarter of the 16th

century.

There is a strong correlation between the Jar dins du Carrousel collection and the assemblages from early contact sites in Northeastern North America. Most of the glass beads from the collection (83%) are also found on First Nations sites dating from the second half of the 16th

century or the first part of the 17th century. It was not always easy to identify the beads because the intense biological and chemical

activity of the deposit altered the surface colors of some of them. Fortunately, a few of the beads had been broken and the true color could be identified by examining the broken fragments (Figure lc). The color of those which had not been broken and showed signs of alteration

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

64 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 35(4)

was determined by scratching and/or wetting a small portion of the surface of the bead. The

turquoise round (Figure la), the apple green round (Figure lb), the bright blue round (Figure Ic), the translucent white-striped round and oval ("gooseberry") (Figures le, f), the blue

white-striped oval (Figure Ig), and the white oval (Figure Ih) beads are very characteristic of the earliest beads found in Northeastern North

America, a period Ian and Thomas Kenyon have termed "glass bead period I" (roughly 1580-1600, according to Kenyon and Kenyon 1983:66). The small to very small round or

circular seed beads are less characteristic, but

they do occur during the early period, primarily on coastal sites, at times in fairly large num

bers?the round and circular bright navy beads

(Figure li, j) are present in Massachusetts, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and New York (Bradley 1983:32; Wray 1983:42; Wray et al. 1991:318;

Auger, Fitzgerald, and Turgeon 1992:62, 1993:64; Whitehead 1993:111, 164; Moreau 1994:36; Diamond 1996:103; Fitzgerald et al. 1997:48-49); the black circular ones (Figure 1A:) as well as the white circular ones (Figure 11) are also present on sites in the same states and provinces, except for Nova Scotia. The lower frequency of these

very small seed beads in early assemblages may be partially related to their size. Unless a fine meshed screen is used, they can easily be overlooked during excavations, especially the blue and black ones, which are often the same

color as the soil. The bright blue tubular beads

(Figure Im) appear quite frequently on glass bead period II sites (1600-1625/30); the black and translucent green tubular beads (Figure In,

o) appear occasionally on glass bead period III sites (1625/30-1650). Their presence in

the Jardins du Carrousel collection, however, is an indication that they could be found on

16th century sites. The frit-core blue oval bead

displaying various patterns of raised white appli

qued lines and dots (Figure Is) is a unique bead

variety (Figure It is a frit-core enamel/faience bead which has lost its glaze) and a good time marker because it is only found on a few early sites: the Micmac Northport and Hopps sites

(Whitehead 1993:44, 66, 165), the Montagnais Chicoutimi site (Moreau 1994:36), the Huron

Kleinburg site (Kenyon and Kenyon 1983:60), the Neutral Carton site (Kenyon and Kenyon 1983:60), and the Seneca Adams and Culbert

son sites (Wray et al. 1987:115, 211). While the total sample size of glass beads is small, the comparatively high frequencies of certain varieties (Table 1, IIa40-14%; IIa48/50-12%; IIbl8/19-16%; IIa55/56-19%) seems to corre

spond roughly with their popularity on American Indian sites. The strong correlation in the

frequency of occurrence on the Jardins du Car rousel site and Northeastern North American sites

suggests that Paris was an important supplier of beads for trade to this part of the world.

There are, however, some important differences between the collection in France and those in Northeastern North America. The only other varieties of beads to appear in any substantial

quantities on sites of First Nations people, are

discoidal and marginella shell beads (Figure lw, v, w). Numerous in the Jardins du Carrousel

collection, faceted beads are almost non-existent in the Northeastern North American collections from the 16th and early 17th centuries. Only a few faceted rock crystal beads (Figures Hi,

jj) have been found in the collections from an

unidentified site in the Mingan Islands in Quebec and from the Mohawk Bauder site in New York

(Rumrill 1991:21-22). The two rock crystal faceted beads from Quebec were excavated by Rene Levesque on the Mingan Islands in 1968.

The site is not identified, but they are cataloged under numbers (MA 2034, MA 3878) and are

preserved at the Centre museographique of Laval University, Quebec City. Only four fac eted rock crystal beads have been found on

the Mohawk Bauder site dated to about 1640. Donald Rumrill believed these to be of Spanish origin because the only other known specimens at the time were from sites in Florida, dated to the second half of the 16th century (Smith 1983:148, 155). Their presence in Paris and on the Mingan Islands in Quebec suggests they could just as easily be of French origin.

Amerindians seem to have preferred the

smooth polished round, oval, and tubular beads to the sharp-edged faceted varieties, at least

during this early period of contact. There also

appears to be a preference for the harder glass, shell, and frit-core beads while the softer and

more fragile jet, amber, bone, and coral beads

(Figures Ix-oo) rarely show up on contact sites.

Only a few jet, coral, and bone beads have been

found in mid-17th century contexts. As far as

is known, no amber beads have been identified

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 65

north of Florida. The colonial St. John's col lection from Chesapeake Bay is the only one

in North America where beads are made up of a variety of materials. Aside from a large number of glass beads similar to those found in Paris, including the ultramarine faceted bead

(Figure \p) not located elsewhere, it contains a combination of black faceted and melon jet beads, round amber beads, as well as round bone beads (Miller et al. 1983:132-137).

On the other hand, several characteristic bead varieties from early Native American assemblages are absent from the Jardins du Carrousel collec tion: the black-striped red round (lib 1, accord

ing to the Kidd classification), the black-striped and cored red round (IVbl), the red-in-white

striped light aqua oval (IIbb23), the multiple layered chevron "star" (Illml), the white-in-blue

striped red round (Ilbbl), the striped tubular

(IIIb3) and the round "eyed" (Ilg, IVg). The

strong presence of these polychrome beads, more difficult and expensive to manufacture, on contact sites, suggests that the consumption of beads was driven, to a certain extent, by Amerindian interest. It is also an indication that Native traders had other sources of supply. These polychrome beads may have been pur chased from Basque fishermen who acquired them in La Rochelle, Bordeaux, and the ports of northern Spain; or from Norman traders supplied at Rouen, a major center of glass manufacture in France; or other European centers of produc tion. They may also have been acquired from

Spanish, Dutch, or English traders along the Atlantic seaboard.

Post-Mortem Inventories of Parisian Bead Makers

To provide more context for the Jardins du Carrousel collection, a survey was undertaken of the notarial archives of Paris in an attempt to locate post-mortem inventories of bead makers. Since there are several thousand Parisian notarial

registers for the second half of the 16th century, it would have been too time consuming to go through them all. To make the research manage able, secondary sources and published inventories of the Parisian notarial records were used to find the names of bead makers and references to some of their post-mortem inventories. Many useful references were found in the magisterial

work of Rene de Lespinasse, Les metiers et

corporations de la ville de Paris (XlVe-XVIIIe siecle) (1886-1897). It quickly became apparent that the bead makers' shops were clustered just north of Les Halles, the central marketplace in Paris. A systematic search was carried out in the records of the notaries residing in this

area; most of the post-mortem inventories were located in the records of four notaries: Filesac

(St. Martin Street), Chazeretz (St. Denis Street), Peron, and La Frongne ( both on Aux Ours

Street). A total of 37 bead makers and 31 post-mortem

inventories were identified for the period 1562 to 1610. Only 26 of the inventories were use

able; five were incomplete, inaccessible, or

gave descriptions of the paternosterers' personal belongings rather than their beads and tools. It is not always easy to read and understand the notarized inventories of this period. The

script leaves much to be desired, because it is

very irregular and sloppy. The records which remained with the notary were copies of the

originals, usually written quickly by young clerks using abbreviations to reduce the costs of

reproduction. The original document was given to the owner and the notary kept a copy as a

warranty against loss or theft. Furthermore, many of the terms used to designate the beads and the tools are no longer employed today. Unfortunately, there are no early treatises on beads that provide descriptions of the manufac

turing techniques, tools, or terminology used

during the 16th and 17th centuries. The most

complete treatise on glass bead making is that of a 19th-century Venetian glassmaker, Dominique Bussolin, titled "The Celebrated Glassworks of Venice and Murano," originally published in Italian and translated into French in 1847

(Karklins 1990). Although it provides a fairly detailed explanation of the two major glass bead manufacturing techniques, the drawn and the lamp-wound, it does not give a thorough description of the different types of beads and tools used for their manufacture, and the trea tise is restricted to glass bead production. Dider ot's mid-18th-century encyclopedia provides names and illustrations of tools, but none of the beads themselves (Diderot and D'Alembert

17751-1765). It contains two entries: one for

"paternosterer" which describes the manufacture of organic beads (bone, wood, jet, etc.) with a

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

66 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 35(4)

turning wheel, and another for enameling describ

ing briefly the production of "enamel" jewelry. There is no entry for glass bead making. Like

wise, the voluminous treatise on metallurgy by the 16th-century German metallurgist, Giorgio Agricola, who claims to have spent two years in Venice and Murano, dedicates only eight pages to glass making, and none to glass beads

(Agricola 1912:584-592). Antonio Neri's (1662) very popular, The Art of Glass, published in Italian in 1612 and later translated into English, German, and French, reveals the "secrets" of Venetian glass making and glass dyeing, but has

precious little on bead manufacture. To complete the information provided by these works, 16th and 17th-century French dictionaries and on the inventories themselves were relied upon,

which sometimes gave clues about manufacturing procedures and bead terminology. Since the notaries were probably not very familiar with the specialized vocabulary, they sometimes went to the trouble of defining certain terms.

Although the sample is not very large and the information contained in the inventories sketchy, it does give a general idea of the occurrences of materials, shapes, sizes, and colors. The bead materials listed in the inventories and their

proportions are very similar to those found in the Jardins du Carrousel collection (Table 2). As in the archaeological collection, glass, enamel, and

jet are the primary materials, followed by shell, amber, coral, cornelian, chalcedony, rock crystal, wood, horn, bone, copper, and ivory. The only difference is that there is a larger variety of materials in the inventories and a larger propor tion of glass, enamel, and jet beads. Glass and enamel represent more than half (51.5%) of the beads listed in the inventories, a figure slightly higher than that of the Jardins du Carrousel collection (44%). In keeping with the practice followed in the inventories, glass and enamel are

separated even though enamel is really a form of glass. According to Bussolin's 19th-century treatise, the term enamel ("email") is used to

designate high-quality glass beads, also known under the Italian word conteries (the brilliance is enhanced by the addition of lead oxide),

whereas the word glass ("verre") is used for

ordinary and cheaper types of beads, sometimes called rocailles (Karklins 1990:69-70). A care

ful examination of the post-mortem inventories indicates that during the 16th and early 17th

centuries the word enamel meant, quite on the

contrary, a lower grade of opaque or colored

glass.

There were in fact four categories of glass beads designated by the Parisian notaries of this

period: crystalline, glass, enamel, and "turquin" (undoubtedly the round turquoise beads, IIa40 in the Kidd classification). For example, the

inventory of Jehanne Gourlin in 1573 lists all four types: crystalline of several colors in the form of tubes or rods ("canon de plusieurs couleurs de cristallin"), glass beads ("perles de

verre"), enamel in the form of beads and tubes or rods ("grains d'email et canons d'email"), and turquins ("turquyns" are in a category of their own, perhaps because of the very particular chemical makeup of these beads) (Archives Nationales, Minutier Central des

Notaires [ANMCN] 1573:IX-154, 20 October). The rather high price of crystalline beads indi cates they were made of high quality translucent

glass and were manufactured of the same mate rial that was used to make crystal drinking glasses. Not surprisingly, the same word is used to designate beads and glasses?for example, the

inventory of glass-maker Jean Delamare lists 60

glasses of "cristallin" (ANMCN 1574:IX-155, 26

January). Crystalline beads were manufactured with quartzite pebbles containing high quantities of silica (up to 98%). These pebbles were heated and ground into a fine white powder, and then mixed with fluxing agents?especially sodium carbonate (that made from the ashes

TABLE 1

MATERIALS OF BEADS FROM PARISIAN POST MORTEM INVENTORIES 1562-1610

Glass 28.5%

Enamel 23.0%

Jet 16.3%

Shell 6.6%

Amber 4.8%

Coral 4.8%

Rock Crystal 4.4%

Cornelian 2.4%

Chalcedony 1.2%

Wood 1.2%

Bone 0.8%

Horn 0.8%

Copper 0.4%

Ivory 0.4%

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 67

of Syrian or Egyptian sea-weed was considered the best), as well as some calcium, potassium, and magnesium. The mixture was placed in a

reverberatory furnace and heated at approximately 800?C for a few hours. The now liquid masse was poured into crucibles and heated at 1,200?C in the main furnace for one to two days. At this stage, manganese or metal oxides could be added to color the glass or enhance transparency. The molten glass was then ready to be blown or

drawn into rods or tubes (Trivellato 2001). The less expensive glass and enamel beads

would have been manufactured with cruder

vitrifying and fluxing agents, and they would have been fused for a shorter period of time,

given that raw materials and fuel generally represented three-quarters of the production costs of finished crystal and glass objects (Trivellato 2001). The prices of glass and enamel beads were similar and they appear to have the same status. In the post-mortem inventory of Gabriel Bellanger, the notary priced some of the

glass and enamel beads together, clearly indicat

ing that their values were similar (ANMCN 1585:XLV-160, 1 October). Regarded as very

poor quality, the oval frit-core glazed blue beads with white appliqued lines and dots, so charac teristic of this early period, are described in the inventories as being made of enamel ("olives a cottes mouchetees aussi d'email") (ANMCN 1603:1-41, 3 May). It is legitimate to think that the frit-core enamel/faience beads would have been included in the enamel category since they were fired and had an enamel type glaze. In the case of the characteristic blue oval bead, the raised white appliqued lines and dots appear to have been applied to the glaze. Fine white

glass thread was likely fired onto the bead with an oil lamp to produce the motif. These frit core beads are not mentioned in the Bussolin treatise probably because they were no longer being manufactured in the 19th century. There are other examples of mid-19th-century terminol

ogy not applying to the 16th century?certain terms, such as conteries and rocailles, are never

mentioned in the 16th-century notarial records. Beads were worked into all sizes and shapes:

oval, round, circular, discoidal, tubular, melon, and faceted. As in the Jardins du Carrousel

collection, round and oval appear to be the

preferred shapes; faceted beads are also preva lent. Tubular beads are less frequent; however,

they are present early?the inventory of Jacques Leroy, drawn up in December 1562, contains

large numbers of them (ANMCN 1562:LIX

25, 28 December). Parisian bead makers used

specialized terms to designate the shapes of the

beads: olive ("olive") for oval, flute ("flute") or canon ("canon") for tubular, cut ("taille en

miroir," "taille a facette" or "taille en plein") for faceted, blackberry ("mure") for the corn

bead (Wild according to the Kidd classifica

tion, Figure Iq, r), and glandular ("facon de

gland") for the acorn shaped beads (Figure \dd). "Strawberry" beads ("a la fraise") may have been the melon shaped ones because the word

strawberry was used in 16th-century France to

designate the fashionable high collared ruffs

shaped like a melon (Figure Ibb). The nota

ries very seldom designate medium size beads

("moyennes"); but large beads are often described as big ("grosses"), and small to very small beads

by terms like grain ("grains"), small ("petites"),

tiny ("menues"), or seed ("semances"). Here

also, the color spectrum is restricted to basic colors: black, white, red, turquoise, blue, violet, and green, in that order; yellow is the only other color mentioned and it occurs only once. The

presence of polychrome beads is suggested by the expression "tubes of several colors"

("canon de plusieurs couleurs"); however, it does not occur frequently, which leads to the conclusion that the majority of beads inventoried are monochrome.

Some beads are described as imitations of Italian models and others as being imported from Venice or Milan. Jeanne Gourlin had in her shop some 43,000 "turquins of the manner of Venice," indicating they were made in the Venetian style. The word "turquin" is defined in dictionaries of the time as a "Turkish [hue] between blue and azure" or "Venetian blue"

(Cotgrave 1950; Desainliens 1970). In the post mortem inventories, they are almost always designated as blue. Some beads were imported from Italy because the same inventory also lists 100,000 "false glass pearls from Venice"

(ANMCN 1573:IX-154, 20 October). Likewise, the shop of Judith Rousselin, wife of the deceased Pierre Rousselin, had in it 17 pounds and 2 ounces of marguerites ("margueritaires") from Milan (ANMCN 1584:XCI-130, 22 March). In Bussolin's 19th-century treatise, marguerites

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

68 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 35(4)

(daisies) designated small Italian embroidery beads of enamel and colored glass. In the French dictionaries of the late medieval period and the 16th century the definition is more

restricted?the marguerite is described simply as a fine white and round pearl (Huguet 1961;

Godefroy 1982). These references to imported beads in the inventories are exceptional. The vast majority of the beads were made by the bead makers themselves because the inventories often refer to equipment and tools used in the

manufacturing process: marble or clay furnaces

("fourneau de marbre" or "fourneau de terre") to fuse glass; iron pestles and morters ("mortiers et pilons de fer") to crush materials for making the frit; slabs of marble or stone ("planche de marbre blanc" or "pierre de Lyon") with

gathering irons ("mollets") for retrieving and

marvering the glass; pincers ("tenailles") for

drawing molten glass into canes or rods; iron molds ("rouelles de fer") for molding glass or

enamel cakes; lamps ("lampes") and bellows

("soufflets") for making lamp-wound beads; copper pans ("ecuelles de cuivre") to tumble

beads; tin screens ("sasets de fer blanc") for

sorting beads; scissors and tongs ("paires de

ciseaux") to cut and manipulate them; knives

("couteaux") and chisels ("ciseaux") to cut

organic beads; turning wheels ("rouet") to turn and polish beads; wooden oak molds for shaping turned beads ("moulures de bois de chene avec

leur rouet"); and files ("limes") to facet them. The Parisian bead-makers were part of a

recognized guild (Lespinasse 1897 [2]:96-97) and were still designated as paternosterers ("patenostriers")?a loan word from Italian

meaning rosary bead makers?because beads had been used in late-medieval Italy almost

exclusively for making rosaries. By the second half of the 16th century, paternosterers were

manufacturing beads and related products for a

large variety of uses: beads for rosaries, but

also for rings, bracelets, necklaces, belts, dresses, and hats. They manufactured glass earrings, buttons, and cupids, even glass tooth-picks. Although most simply designated themselves as paternosterer, some hinted at a more special

ized type of activity by using terms such as

paternosterer of jet or paternosterer of enamel. An examination of the equipment and tools listed in the inventories indicates the Parisian bead makers were involved in the manufacture

of at least four different categories of beads:

organic turned beads, drawn glass beads, mold

pressed glass or enamel beads and lamp-wound glass beads. Half a dozen were specialized in the production of turned beads made of organic

materials. Their workshops appear to be small and equipped with simple tools for cutting, turning, and polishing beads: a workbench, knives, chisels, files, grindstones, a turning wheel ("rouet" and sometimes the word "moulin" is used), iron drills ("forets"), and threaders

("enfileurs"). Hugues Marchonaye had nothing more than a workbench, a turning wheel, a mold, several files, and a "grindstone from Tripoli for polishing jet" (ANMCN 1579:XX-135, 19

May). Most of these paternosterers concentrated on one type of material?for example, Hugues Marchonaye, Denis Hende, and Gregoire Saulsaye worked jet whereas Jehan Pieron favored shell. His inventory listed more than 500 shell beads, 12 whole shells, three grinding wheels equipped

with belts, and 37 oak molds of different lengths to hold the beads (ANMCN 1581:XX-128, 7

January). Only Jehan Dulaye and Crespin Hebert were equipped to turn out beads of several types of materials: jet, coral, shell, and amber.

The majority of the bead makers manufactured drawn glass and enamel beads, which demanded more equipment and labor than the organic beads. Although the production of drawn beads remained a cottage industry, with the workshops generally located in the homes of the bead

makers, it required at least one furnace to melt the frit and a fair amount of space to draw the

molten glass into tubes or canes. With an iron blow pipe, the glass maker would blow a pocket of air into the mob of molten glass, and two

helpers would quickly grasp the fusing glass with gathering irons and pull it by running in

opposite directions, forming a perfectly uniform tube with a hollow cylinder in the middle cre

ated by the air pocket. Once hardened, the

tubes were cut into the desired lengths and the

ends rounded off with a grinding instrument to make tubular beads. To make oval or round

beads, the tubular pieces of glass were mixed with sand and charcoal in copper or iron pans, heated in the furnace, and stirred continually with an iron rod. The longer the beads were

stirred, the rounder they got. The beads were

then set aside to cool, screened to separate them

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 69

from the sand and charcoal, polished in bags of sand and bran, and threaded on strings according to size and quality (Kidd 1979; Smith and Good 1982; Sprague 1985; Opper and Opper 1991). Several of the bead makers of our sample appear to have been fusing glass and drawing it into tubes in their workshops. The shop of the deceased Pierre Rogerel contained 684 pounds of sodium carbonate ("soude"), commonly used as a

fluxing agent, and 290 pounds of coloring agents ("preregot autrement dit couleur") (ANMCN 1573.XCI-124, 11 March). Mold-pressed beads were formed of glass or

enamel/faience in a mold (Sprague 1985:95-97). The glass variety were made by pressing plastic glass into molds, often in a pliers-like device, of the desire size and shape. When cooled they were removed and the mold seam might be

ground and polished. The enamel/faience type were made of wet paste of quartz fit with an

alkaline flux in metal or wooden molds. The holes were made by wires which was removed after the bead was dry. They were then fixed in a furnace and given a salt glaze. Parisian bead makers often combined the production of drawn and mold-pressed beads because the two

processes used many of the same tools. The 1584 inventory of Georges Ferre, which

lists enamel beads, had all of the equipment and tools necessary to draw or mold glass beads: two furnaces (a large and a smaller one), cru

cibles, three workbenches, two chairs, a marver

ing stone from Lyons with its gathering iron, seven pincers, boards to set the tubes on the

ground during the cooling process, perforated iron plates, an iron pestle and morter, nine dozen iron molds ("rouelles de fer"), two threaders, files, boards, and small wooden boxes ("layettes") for storing beads (ANMCN 1584:XCI-130, 6

April). Ferre may have employed as many as a dozen workers. Benoit Vincent's workshop was even bigger?his inventory lists three furnaces, four workbenches, molds, many iron plates, two

pairs of scales, and a turning wheel ("rouet"). He was specialized in the production of enamel and glass beads because the 50 square and round

boxes, made of white spruce, as specified in the inventory, contained primarily these types of beads. His inventory also mentions 80 lb. (36 kg) weight of enamel tubes of different colors and 40 lb. (18 kg) weight of white enamel in tubes as well as in cakes (ANMCN 1603:1-41, 3

May). Both Giorgio Agricola and Antonio Neri indicate that the larger workshops were equipped

with three furnaces: the first for turning frit

into molten glass, the second for re-melting the glass cakes to manufacture glass products, and the third for slowly cooling the glass objects to prevent them from breaking (Agricola 1912:586-589; Neri 1662:239-249). The smaller

workshops would have two or only one furnace, in which all three operations would have to be carried out. Some paternosterers seem to have been purchasing glass and enamel tubes from

glass factories rather than manufacturing them themselves. Jehanne Gourlin's inventory lists some 1,112 lb. (504 kg) weight of crystalline and enamel canes in cases and only one small

furnace, suggesting her operation was specialized in transforming the canes into tubular or rounded beads (ANMCN 1573:IX-154, 20 October).

The manufacture of lamp-wound beads was much less common. These were made with solid glass canes of various sizes heated with a

lamp and a bellows used to direct and increase the temperature of the flame. The heated glass cane would wind itself around the iron wire as it melted and form a rounded bead. The bead could be further shaped by the movement of the worker's fingers or the use of small molds

according to Bussolin (Karklins 1990:74). Only two inventories listed lamps and bellows. Symon Grue's 1584 inventory mentions a workbench, a bellows ("soufflet"), a lamp ("lampe"), and iron

wire, but also a furnace, three morters and three

pestles, iron boards, chisels, pincers, and other tools usually employed in the manufacture of drawn beads (ANMCN 1584:IX-111, 23 Octo

ber). The inventory suggests a hybrid opera tion combining the production of drawn and

lamp-wound beads. Anthoine Grandsire's oper ation seems to have been more specialized; his workshop contained only a bellows "for bead makers" ("de paternostrier") and a work bench with "several lamps" ("plusieurs lampes") (ANMCN 1630:XLII-77, 22 March). Interest

ingly, two display panels of beads are listed as exhibited in his "boutique" which contained enamel as well as "faience" (frit-core) beads. Since these are the first inventories to mention bellows and lamps, they suggest that it is around this time that lamp-wound glass beads began to be manufactured in Paris. According to Bus

solin, the technique for making these types of

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

70 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 35(4)

beads was invented in Venice in 1528 (Karklins 1990:75); it is not surprising that it took some time before they were introduced into France, given the secrecy surrounding the manufacture of glass beads in Venice.

The numbers of bead makers seem to increase

during the second half of the century as they become progressively more involved in the

clothing industry. Boniface Marquis, an active member of the guild, gave paternosterer as his

profession in 1562 (ANMCN 1562:IX-25, 28

December), but was designated as haberdasher

("mercier") in his post-mortem inventory of 1581 (ANMCN 1581:IX-162, 14 February). Several of the inventories of the last quarter of the century listed sewing goods along with beads: thread, needles, thimbles, scissors, ribbon, lace, and cloth (ANMCN 1578:111-437, 13 July; 1580:111-191, 10 January; 1578:XCI-130, 22

March; 1603:1-41, 3 May; 1610:X-13, 21 June). In some cases, gloves, belts, and purses are

described as being embroidered with beads, which is an indication that clients were leaving these accessories in shops to have beads sewn

onto them (ANMCN 1569:111-436, 2 May; 1570:111-322, 30 May; 1572:LIX-27, 19 Febru

ary). The use of beads to decorate garments became widespread during the 16th century with the development of the Renaissance fashion of

embellishing clothing with precious stones and beads (Boucher 1996:191-203); it is this new

and growing market that probably explains the

upsurge in the number of bead makers rather than simply the manufacture of rosaries. Beads embellished hats, gloves, boots, belts, shirts, and

coats, and ever more frequently bed canopies, cushions, altar cloths, and chasubles (De Farce

1890:37; Rocher 1982; Wolters 1996:36-39). Costume books attest to the increased associa tion of beads and precious stones with costume

during the second half of the 16th century

(Bruyn 1581; Vecello 1590; Glen 1602). Amer indian traders likely saw them on the bodies and the clothing of ship captains or even ordinary sailors. Mariners often wore shell necklaces or bracelets as proof of their travel to distant lands and also perhaps as a way of identifying themselves with the sea. It was a well-known custom among seamen to wear a spiral brass

earring to protect oneself against bad eyesight (Witthoft 1966:205).

France became a major center for the manu facture and trade of beads during the 16th

century. Members of the court and wealthy merchants encouraged Italian glass bead makers to practice their trade in France. Glass factories

were established in Lyons, Nevers, Paris, Rouen, Nantes, and Bordeaux. By the end of the cen

tury, they were present in most of the major French cities (Barrelet 1953:62-65, 91-95). These glass factories produced colored glass in the form of rods and canes on a large scale and sold them to paternosterers who worked them into beads of different forms and sizes. France

exported large quantities of beads to England and North America (Kidd 1979:29); they were

purchased by merchants for the North American trade at La Rochelle (Archives Departementales des Charentes-Maritimes 1565:3E 2149, 20 June), at Bordeaux (Archives Departementales de la Gironde [ADG] 1587:3E 5428, 5 February) and,

primarily, at Paris (ANMCN 1599:3 November). Merchants in the provincial cities were often sup

plied by Parisian bead makers or haberdashers. Charles Chelot, one of the most prominent bead merchants (mercer/haberdasher) in Paris, provided beads to Guillaume Delamarre of Rouen, Samuel

Georges of La Rochelle, and Pierre Bore of

Bordeaux, all merchants actively involved in the early trade to Canada (ANMCN 1610:X-13, 21 June).

The presence of shell beads in the post-mor tem inventories as well as at the Jardins du Carrousel collection is an important find because it has been assumed by most North American bead researchers that shell beads were exclusively of Aboriginal origin (Beauchamp 1901; Ceci

1989; Sempowski 1989; Hamell 1996). Several Parisian bead makers specialized in the manu

facture of shell beads, commonly called porcelain ("porcelaine") in French, a term derived from the Italian porcellana which designates the cowry shell (Hamell 1992:464; Greimas 1992). When the word porcelain is used in the inventories, there is no question that the notaries are refer

ring to shell beads and not frit-core or faience

beads; whole shells or scraps of unused shell

("coquilles") are mentioned, but none of the tools needed to manufacture glass and frit-core beads are listed (ANMCN 1570:111-321, 30 May; 158LXX-128, 7 January; 159LXXIII-135, 13

June). When the terms enamel and porcelain are

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 71

sometimes used together in the same inventories; the notaries are clearly referring to different beads because the latter are always more expen sive than the former, or than most other beads for that matter. Furthermore, the word porcelain is used to designate shell beads in all of the

early French travel literature of North America

(Vachon 1970:260; Karklins 1992:13) as well as

in the royal charters (Lettres patentes) of the Parisian bead makers (Lespinasse 1892[2]:109; Franklin 1895 [16]:156). Some of these shell beads were making their way to North America. Charles Chelot, who had strong ties to many of the merchants outfitting ships to Canada, sold large quantities of shell beads in 1599 to Pierre Chauvin, a well-known Canadian fur trader (ANMCN 1599:XCIX-65, 3 November). Lescarbot also specifies, in his travel account, that the Indians "make great use of Matachiaz,

[the Micmac word is employed here to designate marine shell beads] which we bring to them from France" (Lescarbot 1612:732). Since shell beads were already ornamental and valued

objects for most First Nations groups of the

Northeast, it is not surprising that they would have been attracted early on by this familiar

and, at the same time, exotic object of European origin. Shell beads remained an important French trade item throughout the colonial period. The King's stores in Quebec City always kept large quantities of shell beads on hand and they

were much more expensive than glass beads.

According to Nathalie Hamel, one shell bead was worth 1,224 glass beads during the period 1720-1760 (Hamel 1995:13-14). Likewise, shell beads always far outnumber glass beads in the inventories of trade goods from the trading posts of the Chesapeake during the 17th century (Miller, Pogue, and Smolek 1983:127-130).

It should be possible to visually distinguish the Native manufactured shell beads from the

European ones. The latter would have been manufactured with iron drills and should have more regular forms and shapes. Unfortunately, it appears that chemical trace element analysis

will not be very helpful in identifying the geo graphical origins of the shell because, accord

ing to Cheryl Claassen and Samuella Sigmann (1993:336, 345), most beads are not large enough to provide reliable data.

To better understand the cultural transfer of shell beads from France to America, it will be

important to have more information on the dif ferent types of French shell-beaded objects and the ways in which they were used in France. There is a substantial body of information on Native American uses of shell bead, but surpris ingly little on their usages in Europe. French

practices may have inspired Amerindian adapta tions and innovations. Although such a research

agenda is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning that the inventory of Jehan

Pieron, who specialized in the manufacture of shell beads, lists a belt made of white shell beads ("corps de ceinture de porcelaine blanche") (ANMCN 1581:XX-128, 7 January). The use of the word "corps" (body) in French suggests the beads were braided into the belt. This may have been the precursor of the North American

wampum belt. Beaded belts appear to have been fashionable at the time, several have been encountered in the inventories: a belt garnished with enamel grains ("grains d'email en garniture de ceinture," ANMCN 1573.IX-154, 20 Octo

ber); a small belt of white and black enamel

garnished with small paternoster beads ("petite ceinture d'email noir et blanc garnie de petits patenostres," ANMCN 1584:XCI-130, 6 April); and a belt of enameled gold stones containing 121 round pearls ("une ceinture de pierres d'or emaillees contenant 121 perles rondes," ANMCN

1631:VI-210, 16 June). Shell beads were also used to decorate purses. Jehan Dulaye's inventory lists five purses embroidered with

white shell ("cinq escarcelles faites de coquilles blanches brodees," ANMCN 1570:111-321, 30

May).

A Chronology for French Trade Beads in Northeastern North America

The evidence of trade of French marine shell is an invitation to open up North American bead research to other types of beads, and to all

European trade goods for that matter, in order to gain a better understanding of the chronology of contacts and their impact on First Nations

groups. Although glass beads were a major trade item, they appear rather late on North American contact sites, long after shell and

copper beads for example, and their use as a time marker has led us to assume that trade before glass bead period I (ca. 1580-1600) was quantitatively insignificant and, therefore,

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

72 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 35(4)

unimportant. There has been a tendency to concentrate on the larger collections of glass beads and to forget the isolated shell beads, the rolled copper beads, and the few scraps of iron found on earlier sites. These first small and

apparently trivial objects may have had a more

significant impact on Native groups than has been assumed until now. Our attention is now turned to this earlier period and hypothesize that the European presence was felt very early in the 16th century and that French trade goods increasingly circulated in Northeastern North

America from the time of the Verrazzano and Cartier voyages in the 1520s and 1530s.

In the Northeast, marine shell beads are the first exotic objects to appear on Native sites of the interior. They are all but absent from the

archaeological record during the late prehistoric era (A.D. 1000 to 1500), a period of profound localism showing little if any archaeological evidence of trade or contact between groups (Bradley 1987:25). Most of the beads found on these sites are made with local materials: freshwater shell, animal bone, deer phalanges, and mammal teeth (Wray 1987:147; Ceci

1989:68; Lennox and Fitzgerald 1990:423; Rams den 1990:370-371). The late prehistoric sites where a few discoidal and/or tubular marine shell beads have been excavated are, in fact, so

late, they could be considered to date from the early historic period: one bead on the Seneca Alhart site (1440-1510) (Hamell 1977), another on the Mohawk Elwood site (1475-1500) (Kuhn and Funk 1994:78-79), three on the Huron Kirche site (ca. 1495-1550) (Pendergast 1989:98), nine on the Saint Lawrence Iroquoian

Mandeville site (ca. 1500) (Chapdelaine 1989:102,

Figure 7.15) and a dozen on the Onondaga Barnes site (ca. 1500) (Bradley 1987:42). Fur

thermore, the dates indicated for these sites are those given by the authors at the time of the study. In recent years, dates of sites in

western New York have been advanced in time? for example, Alhart to 1500-1550, Elwood to

1500-1535, and Barnes to 1540-1560 (Lenig, pers. comm.). Since marine shell has been assumed until now to be of Native American

origin and the presence or absence of European trade goods has been the primary criterion for

dividing the prehistoric from the historic periods (Hamell 1992:458), there has been a tendency to push the dates of sites containing marine

shell beads back into the prehistoric period. If the introduction of marine shell were a contact related phenomenon, then these sites could just as easily be placed in the early historic period.

The Iroquoians may have acquired shell beads from Europeans or, while waiting for them, from coastal Algonquian groups who began manufacturing beads at about the time of these first contacts (Ceci 1989:72; Fenton 1998:226). From the information provided by the Jardins du Carrousel collection, it appears legitimate to hypothesize that the discoidal and marginella shell beads were of European origin and the tubular shell beads (proto-wampum) were of

North American provenience. Native groups encountered Europeans during the very first decades of the 16th century when English, French, and Portuguese fishing vessels began establishing shore stations to dry cod (as early as 1501) and when explorers such as Gaspar Corte Real (1501) and Thomas Aubert (1509) not only encountered Indians along the coasts, but also brought some back to Europe to be sold as slaves or exhibited as curiosities (Quinn 1977:123-131). These voyages were followed

by those of Verrazzano (1524), Gomes (1525), and Cartier (1534-1542). Verrazzano exchanged gifts, including "azure crystals" (bright blue

glass beads) (Winship 1905:15-16), with several Native groups of New England, and Gomes traded European goods for sables and other valuable furs with the First Nations of Cape Breton Island (Quinn 1979[1]:274). During his first voyage in 1534, Cartier presented the Micmacs he encountered in Chaleur Bay with

hatchets, knives, beads ("patenostres"), and other

wares; a few days later, he gave the group of

Iroquoians at Gaspe "knives, glass beads, combs, and other trinkets" (Bideaux 1986:112, 114). During his second voyage in 1535-1536, Cartier

again distributed large amounts of French goods in the form of gifts: he gave the women of Stadacona (present-day Quebec City) knives and glass beads, and the chief two swords and two large brass wash basins; on the way to

Hochelaga (present-day Montreal), he distributed knives and beads; at Hochelaga, he provided the men with hatchets and knives, the women

with beads and other "small trinkets," and the children with rings and tin agnus Dei (Bideaux 1986:139, 143, 149, 150, 155). Upon returning to Stadacona the same year, he gave the men

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 73

knives "and other wares," and a tin ring to each of the women. Throughout the long winter spent there, Cartier exchanged knives, awls, beads, and other "trinkets" for foodstuffs (Bideaux 1986:159.

162). These represent fairly large quantities of beads and other goods, thus some should appear in the archaeological record. Narratives of the European presence certainly

circulated quickly and widely, and Indian groups must have traveled to the coasts to see these

strange creatures. The St. Lawrence Iroquoians encountered by Cartier on the Gaspe Peninsula in 1534 had likely come with this intention; indeed, the absence of Iroquoian material culture in the archaeological record of the area points towards a recent and sporadic occupation rather than a long-lasting seasonal migratory movement

(Tremblay 1998:116). The small amounts of marine shell beads that appear on sites of the interior may very well be the first tangible signs of migratory movements to the eastern seaboard to establish contacts with Europeans. Although groups from the interior may have also been

acquiring European shell beads through trade with coastal groups, one should not exclude the

possibility of seasonal expeditions because it was undoubtedly important for Amerindians to see and to have direct contacts with Europeans. As Cheryl Claassen and Samuella Sigmann (1993:334) have pointed out, there has been a tendency in the archaeological literature to

presume rather than demonstrate that trade is the

transport mechanism responsible for the presence of exotic materials on sites. The movement of

objects always entails the movement of peoples, at least to a certain extent.

European copper beads occur on Algonquian and Iroquoian sites during the second quarter of the 16th century, slightly before glass beads. Small pieces of copper cut from kettles, often rolled into tubular beads, and some rare iron

objects (awls and celts), sometimes found in association with marine shell discoidal beads, may be considered a horizon style artifactual

assemblage for this period. As James Bradley has pointed out, the first European objects on

Algonquian early contact period sites in New

England are small brass/copper beads as well as small pieces of sheet brass or copper (Bradley 1983:30). These same materials turn up on

Iroquoian sites of the interior. Copper beads and a few iron awls and celts are found on

Huron sites from the early to mid-16th century (Ramsden 1990:373). The first object, indisput ably of European origin, to appear in Neutral

archaeological assemblages is a rolled brass bead recovered from the MacPherson site dated to the middle of the century (Lennox and Fitzgerald 1990:429). Further to the south, on the Onon

daga sites, scrap pieces of copper were located on sites from the 1525-1550 period: one piece at Temperance House and two at Atwell (Bradley 1987:69). The Seneca Richmond Hills site, dated 1540-1560, contained a tubular copper bead, a copper ring, a tiny scrap of sheet copper, and iron nail (Wray et al. 1987:240; Kuhn and Funk 1991:80). The Mohawk Garoga site

(1525-1545) also had a small but compelling assemblage of copper objects: two tubular

beads, an unidentified ornament, and a piece of scrap (Snow 1995:154-158). Most of the shell bead assemblages that appear on sites from this period are dominated by the same types of shell beads found in the Jardins du Carrousel

collection?centrally perforated small discoidal beads and an occasional marginella bead (Lenig, pers. comm.).

This characteristic artifactual assemblage, found on numerous sites spread over a large part of the Northeast, very likely corresponds to the

development of trade with French fishermen and

Basque whalers on the Atlantic seaboard in the 1530s and 1540s. The number of French cod

fishing ships outfitted to Newfoundland rose in earnest during this period. In the Bordeaux notarial archives, for example, the vessels outfit ted for the cod-fishery increased from 1 or 2

per-year in the 1530s to more than 20 per-year in the 1540s (Bernard 1968:805-826). These

high levels are corroborated by those of two other large French ports actively involved in the Newfoundland cod fishery?La Rochelle and Rouen. These three ports alone were outfitting more than 150 ships a year towards the end of the 1550s (Turgeon 1998:590-591). As the number of vessels increased, they spread out into the Strait of Belle Isle and the Gulf of the Saint

Lawrence, and set up shore stations on land to

dry cod. In the late 1530s, French and Spanish Basques began fishing and hunting whales in the Strait of Belle Isle; there may have been as many as 15 to 20 large whaling ships and

1,000 European men on the Labrador coast by mid-century. These vessels would have had on

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

74 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 35(4)

board copper kettles for cooking meals for crew

members; additionally, each whaling ship would have carried as many as three or four large copper cauldrons used in the rendering of whale blubber into train oil. Fishermen and whalers had in their possession all sorts of iron tools and objects?axes for making ship repairs and

building shore stations, knives for gutting fish and cutting whale blubber, and large amounts of nails for constructing wooden docks, platforms, and shelters.

Coastal Algonquians and even Iroquoians from the interior traded with Europeans at these seasonal shore stations. At least two of the

groups Cartier met during his first voyage to the St. Lawrence region in 1534, appeared familiar with European trade?the Micmacs of the Bay of Chaleur who made signs to him to come to

shore and held skins on sticks, and the Montag nais group he encountered on the North Shore of the St. Lawrence "who came freely aboard his ships as if they had been Frenchmen" (Cook 1993:20, 31). St. Lawrence Iroquoians from the

Quebec City area were definitely trading with the Basques in the Strait of Belle Isle in the 1530s and 1540s. In the depositions taken from

Basque fishers by the Spanish Crown in 1542 to inquire about the Cartier voyages to Canada, a ship's captain from Bayonne, Robert Lefant, testified that he had been cod-fishing five years earlier, that is in 1537, in a port called "Brest"

(Riviere St. Paul), where the Indians traded "marten skins and other kinds of skins" for "all kinds of ironware." He added that the "Indians understand any language, French, Eng lish, and Gascon, and their own tongue" (Biggar 1930:453-454). In order for the First Nations to have acquired even a minimal knowledge of

European languages by 1537, trade relations must have been established some time earlier.

Another witness, Clemente de Odelica, from

Fuenterrabia, who had set sail in a vessel from

St. Jean de Luz in 1542," said that "many sav

ages came to his ship in Grand Bay [Strait of

Belle Isle], and they ate and drank together and were very friendly, and the savages gave them

deer and wolf skins (possibly sea wolves, i.e.

seals) in exchange for axes and knives and other

trifles." Although dressed in skins, Odelica

warned that these were men of skill and that

further up the river the inhabitants were much

the same, "for they gave them to understand that

one of their number was the leader in Canada"

(undoubtedly St. Lawrence Iroquoians). Armed with bows and arrows and pinewood shields, and

having many boats (undoubtedly canoes), they claimed to have killed more than 35 of Cartier's men (Biggar 1930:462-463). The presence of St. Lawrence Iroquoians in this area at that time is also supported by the archaeological record; the rim sherd of a St. Lawrence Iroquoian pot was found inside a collapsed shelter at Red

Bay, Labrador, dating to about mid-century (Chapdelaine and Kennedy 1990:41-43).

The Basque appear to have pursued their trade with the First Nations in this area, at least intermittently?the 1557 will of a Basque fisherman from Orio mentions cueros de ante

(probably caribou hides) from the "New Found Lands" (Barkham 1980:54). European fishers and whalers may have been venturing up the St. Lawrence themselves in search of furs, for in

1610 an elderly seaman refers to ships going to

Tadoussac for the last 60 years, which suggests Europeans had been in the area since 1550

(Biggar 1922-1936[2]:117). In 1545 the French

navigator Jean Alfonse noted in his sea rutter that large quantities of fur were available on

the Acadian peninsula and the coast of Maine,

suggesting trade was already taking place there

(Biggar 1901:31). Fishers were expected to

bring back all types of marketable merchandise from the New World, not just fish, train oil, and whale blubber, as indicated in the hundreds of

charter-parties and supply contracts examined from Bordeaux. The following formula appears in the contracts around mid-century to describe the return cargoes: "fish, oil, grease, merchan

dise, and other things . . . from the New Found

Land." Sometimes the stipulation that "the master and crew shall neither conceal nor traffic in anything . . . from the suppliers" was added,

suggesting that fishermen were illegally portaging hides and pelts in their trunks. Some North American pelts were reaching Paris during this

period; in 1545, beaver pelts are referred to for

the first time in the post-mortem inventories of

Parisian furriers (Allaire 1995:82). In the late 1550s, out of this portage trade,

carried out seemingly on a small scale, grows a more sustained commercial activity organized by merchants supplying vessels with items selected for the fur trade. Notarial records reveal more

than a dozen outfittings for the trade on "the

This content downloaded on Mon, 31 Dec 2012 17:10:42 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

-

Turgeon?FRENCH BEADS IN FRANCE AND NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICA 75

coast of Florida" between 1558 and 1574. Since the La Rochelle and Rouen notarial records have not been well preserved for this period, the actual numbers of ships outfitted for "Florida" must have been much higher. Most of the ves

sels were Norman, from the ports of Rouen, Le

Havre, and Honfleur. The few outfitted at La Rochelle and Bordeaux were partly sponsored by Norman merchants or captained by men

of Norman origin, such as L'Aigle de La

Rochelle, a new 100 ton vessel bound in 1565 for "Florida to fish for cod and trade goods" (Archives Departementales des Charentes-Mari times 1565:3E 2149, 21 May, 22 June).

The "coast of Florida" would seem, at first

glance, to indicate the Northeast coast of the Florida peninsula, where the French attempted to establish a colony from 1562 to 1565 (de Pratter et al. 1996:39^8). Yet a careful reading of the records shows that the Florida trade is always

mentioned in conjunction with cod-fishing, which cannot be practiced south of Cape-Cod. In fact, for the Spaniards, "Florida" encompassed a vast

territory stretching over North America from the Florida peninsula and New Spain (Mexico) all the way to Cape Breton Island. Contemporary French maps likewise refer to the "coast of Florida" when designating the whole North American Atlantic seaboard?those of Le Testu

(1556), Levasseur (1601), and Vaulx (1613), for instance (Beguin and Beguin 1984:27-28, 33;

Mollat du Jourdin and La Ronciere 1984:233, 244-249, charts 49, 50, 67, 71). The map of

Jacques de Vaulx, who had been part of a French expedition to map the coasts of North America between 1585 and 1587, appears to be more precise; it indicates the shores of present day Maine, in and around the mouth of the Penobscot River, as being the coast of Florida

(Litalien 1993:134). In the minds of the Norman