NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H OCCASIONAL PAPER TITLE : The Evolution of Sovie t Perspectives on African Politic s AUTHOR : S . Neil MacFarlan e DATE : March 15, 199 2 In accordance with Amendment #6 to Grant #1006-555009, this Occasiona l Paper by a present or former Council Trustee or contract Awardee has bee n volunteered to the Council by the author for distribution to the Government .

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH

OCCASIONALPAPER

TITLE:

The Evolution of Sovie tPerspectives on African Politic s

AUTHOR: S . Neil MacFarlan e

DATE :

March 15, 1992

In accordance with Amendment #6 to Grant #1006-555009, this OccasionalPaper by a present or former Council Trustee or contract Awardee has bee nvolunteered to the Council by the author for distribution to the Government .

NCSEER NOTE

This paper consists of Chapter I from Soviet Policy in Africa : from the Old to the New Thinking; George Breslaue rEd. : Published by the Center for Slavic and East European Studies; University of California, Berkeley, for th eBerkeley-Stanford Program in Soviet Studies . Forthcoming Spring, 1992.

SUMMARY 1

This paper describes the transition in the Soviet view of Africa from a forward ,

ideological, aggressively confronfational and optimistic stance in the early 1970's to th e

opposite in the 1980's . In that sense the paper is already dated, and has been overtaken b y

events, in particular by the bitter lessons learned by the Soviet society from the traumas o f

the last few years . The paper's lasting value, however, may lie in its analytic conclusion tha t

the change of view was the product of learning from reality and experience, rather than

a tactic, and therefore might last into a period when Russia may recoup some measure of it s

earlier influence in Africa .

The table of Contents on the following page shows the topics covered by the author ,

and the text reveals the breadth as well as idiosyncracies of Soviet perspectives and thei r

evolution, reversal even, over the period . For the reader it is a brief immersion into an alie n

symbolism and dynamic, familiar to specialists, and unlikely to be quite eradicated for year s

to come. The author's central point (paragraph 1 above) is well captured in his Conclusion s

(Pp. 47 to 49) .

This paper supplements the author's Final Report to the Council, "The Evolution o f

Soviet Perspectives on Third World Security," distributed February 19, 1992 .

1 Prepared by NCSEER staff.

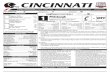

Table of Content s

I . Introduction 1

II . Activism in Theory, 1970's 8a . The Vanguard Party 8b . The Sources of Civil Conflict 1 1c . Liberation in Southern Africa 1 2d . Economic Development 1 4e . Inter-African Conflict 1 6f . Structures of Conflict Limitation 1 6g. The Foreign Policies of African States 1 7h. The Role of External Actors 2 1

III . Modifications 27a. The Vanguard Party & Socialist Orientation 2 8b . The Sources of Civil Conflict 3 1c . The Liberation Struggle in South Africa 32d . Economic Development 34e.

Inter-African Relations 3 8f .

External Actors 39

IV.

Conclusions 47

THE EVOLUTION OF SOVIET PERSPECTIVES ON AFRICAN POLITICS '

S . Neil MacFarlane

I. Introduction

The Soviet-Cuban intervention in the Angolan war in 1974-76 marked the beginnin g

of a period of considerable activism in Soviet policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. The principal

characteristics of this period were :

1. A growing willingness to employ force (indirectly) to enhance the Sovietposition in the region (e .g ., the Angolan and Ethiopian interventions) .

2. A substantial increase in the quantity of arms transferred to the region an din the role of this instrument in policy implementation .

3. A focus on "states of socialist orientation," involving the conclusion o ftreaties of friendship with Angola, Mozambique, and Ethiopia ; theestablishment of institutionalized ties between leading parties in these countrie sand the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) ; and the acceptance bythe USSR and its allies of a substantial role in security assistance .

4. Enthusiastic rhetorical and significant material support for liberatio nmovements in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), South Africa, and Namibia .

More than ten years have passed since this resurgence of Soviet activism in Africa .

During this period the Soviets have been consistently confronted with the difficulty of

stabilizing vanguard party regimes, not to mention the even greater difficulty of furtherin g

their transition to socialism . Friendly regimes in Ethiopia, Angola, and Mozambique ar e

faced with powerful insurgencies . While these insurgent movements benefit fro m

considerable external support, they also have profound internal roots . Popular support fo r

them -- or, more modestly, public apathy or hostility toward the governments -- stems fro m

ethnic and regional disaffection, economic hardship, and governmental mismanagement .

After a decade of "non-capitalist development," the economies of Soviet clients are a

shambles. The only real development proceeding in sub-Saharan Africa is occurring in state s

of capitalist orientation generally hostile toward the USSR (e .g .,, the Ivory Coast an d

Kenya) .

2

In the meantime, in defiance of optimistic predictions about the weakening of th e

position of imperialism in Africa, and most noticeably since the Shaba incidents of 1977 an d

1978, the Western powers -- particularly, France and the United States -- have demonstrate d

that they are unwilling to withdraw from active participation in the politics and militar y

affairs of the region . Their involvement has occasioned serious difficulties for friends of th e

USSR (viz . French and American actions against Libya and American assistance to UNITA

in Angola) . In economic affairs, the twelve years since the Angolan liberation hav e

demonstrated that African states -- including the states of socialist orientation -- have littl e

choice but to participate in the Western- and Japanese-dominated world economy on term s

dictated by the principal capitalist industrial powers . In short, the Soviets have becom e

rather thoroughly acquainted with the vicissitudes of attempting to stabilize their politica l

position and to implant their political and economic model in the African environment .

The fundamental question of this volume is what, if anything, the Soviets hav e

learned from this experience . The assessment of learning must take into account bot h

theoretical development and policy change . Change in theory is of little relevance in gaugin g

the adaptation of a state's perspective on a specific problem unless the practice of that stat e

reflects the change . Likewise, it is difficult to interpret the historical significance of change

in practice without reference to the intellectual context in which it occurs . Attention to th e

evolution of theory gives us at least a partial view of that context .

This chapter addresses the evolution of published Soviet perspectives on Africa n

politics and international relations since 1975 . It asks whether there exists evidence in thi s

literature of the disillusionment, pessimism, and growing caution that one might expect t o

emerge from the last twelve years of experience with radical clients in the sub-Sahara n

region . The discussion is divided into four sections : Soviet comment on the internal politic s

and policies of African states ; discussion of the struggle for liberation in southern Africa ;

analysis of the process of economic development in Africa ; and comment on the internationa l

relations of the regional subsystem .

The discussion of African domestic politics concentrates on the performance of an d

prospects for vanguard party regimes in the effort to lay the basis for the transition t o

socialism, and on the nature and significance of impediments to this process . It also

3

considers Soviet analysis of the roots and significance of civil conflict in African societies .

The section on national liberation in southern Africa examines Soviet discussion of the rol e

of various social and political forces in the struggle for change in the southern section of the

continent, the role of violence in this struggle, and the prospects for successful change . The

section on economic development addresses Soviet evaluations of the prospects for economi c

progress, the methods of obtaining it, and the impediments encountered in the developmen t

effort .

In the section on Africa's international relations, I address the sources of interstate

conflict, the nature and significance of the roles played by external actors, and the potential

for and methods of crisis management and conflict resolution in the region . Africa's impac t

on relations between the two superpowers is also examined .

In analyzing the evolution of the Soviet discussion of these topics, I have relied on a

survey of major Soviet academic, military and party journals (Mirovaya Ekonomika i

Mezhdunarodnye Otnoshenia, Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn', Narody Azii i Afriki, SShA : Politika ,

Ekonomika, Ideologia, the Voenno-Istoricheskii Zhurnal, Morskoi Sbornik, Kommunis t

Vooruzhennykh Sil, and Kommunist) over the years 1975-87, and on a selection o f

monographs produced by Soviet scholars and party officials in the same period . Where

useful, I have also drawn upon declarations of party doctrine and government policy i n

Pravda and Izvestiia, as well as in the electronic media . I have focused principally o n

articles and statements dealing specifically with Africa, though where particularly useful, I

have employed more general treatments of Third World issues as well .

How one interprets a given Soviet source depends on what one determines its functio n

or functions to be . Three functions seem particularly important : disinformation, the

definition and propagation of doctrine, and the airing of debates among experts . Although

deciding which function is being served in any given case is occasionally problematic, i n

most instances one can make reasonably reliable judgements through attention not only t o

what is said, but also who is saying it, what the institutional affiliation of the author is ,

where the statement appears, at what audience it is being directed, and, finally, the historica l

context informing the statement in question . For the purposes of this discussion, both

4

scholarly analyses and doctrinal statements are relevant . The former suggest trends in th e

thinking of the community of specialists . The latter reflect the degree to which these trend s

have filtered up to the level of policymaking .

There is ample evidence to suggest a plurality of perspectives in the analytical an d

policymaking communities on Third World issues .' Given the space limitations of thi s

chapter, I shall not consider these differences in detail, although I recognize their importance

to the subject as a whole . Instead, I shall focus on the dominant tendencies of articulatio n

and how these have evolved over time in response to the accumulation and analysis of

experience in the region and to the spectrum of other internal and external factors whic h

impinge on Soviet policy in Africa .

In order to give the reader some sense of orientation for an analysis which may

appear somewhat alien, if not bizarre, it is useful at the outset to define the parameters o f

opinion and to associate them with policymaking perspectives . At the risk of

oversimplification, Soviet views on these topics range over time between what can be loosel y

called a revolutionary 3 tendency of articulation and a more realistic or pragmatic one .

The former emphasizes the applicability of orthodox Soviet Marxist thought and th e

Soviet experience of political, social, and economic development in Africa . It stresses th e

importance of the establishment of quasi-Leninist parties, reliance on the working class an d

peasantry, class struggle against exploiting indigenous and foreign groups, and the need to

move beyond traditional patterns of social and economic organization to scientific socialis t

forms in the struggle for development . It accepts the necessity of violence in the struggle fo r

liberation in southern Africa and rejects evidence of reformist tendencies in that region . It

emphasizes the role of imperialism as a cause of conflict and an impediment to progress i n

the region, and plays down the role of indigenous forces in this regard . In this sense, the

question of security and development in Africa is situated within the broader zero-su m

scheme of struggle between capitalism and socialism . The imperialist threat is perceived as a

monolithic one -- led by the United States . Hence, South Africa and France, for example ,

are subordinate players in a unified Western imperialist threat to Africa. Inter-imperialis t

contradictions and the autonomy of individual imperialist states are played down .

The role it posits for the Soviet Union in the struggle for complete liberation is a

5

broad one -- involving the provision of political, economic, and military support t o

progressive states in Africa . The capacity of the USSR and the socialist camp to provide a n

alternative to participation in and dependence on the world capitalist economy is stressed . Its

focus in discussing relations with African states is on the states of socialist orientation .

Capitalist-oriented states are dismissed as instruments of imperialism in the latter's efforts t o

dominate Africa . It places little emphasis on the constraints faced by the USSR in it s

economic relations with its African allies . It plays down, if it recognizes at all, the negativ e

consequences of activism in Africa for the central relationship between the superpowers . It

rejects the notion that cooperation with the West on regional security issues is possible .

Western efforts at conflict management and resolution are dismissed as insincere an d

self-interested .

The "pragmatic" or "realistic" view suggests that the African political experience i s

quite specific in character and that, therefore, important modifications of the Soviet Marxis t

model of development are necessary, if indeed the model is applicable at all . It questions the

significance of class struggle as the dominant political phenomenon in African society an d

politics, stresses the weakness in these societies of the classes (the proletariat and th e

bourgeoisie) which are central to Marxist theory, and emphasizes the importance of factor s

indigenous to Third World society (clan, tribe, religion) as determinants of indigenou s

political outcomes .

In such circumstances, integrative efforts at building national unity are necessary .

Governments should attempt to reconcile conflicting tendencies through broad fronts . Under

these conditions, vanguard parties are not necessarily the way to go . Those that have been

established and which rule face a very difficult and lengthy task in pursuing the path o f

socialist orientation . Reversal is possible on this path . It is questionable whether the parties

established on the vanguard model are equal to the task they face . They lack theoretical

sophistication, perseverance in the controlled mobilization of the fragmented population int o

purposeful directed political activity, are often corrupt, and are often excessively hasty i n

their efforts to make the leap to socialism. The consequences of their efforts to do so are

often economically and politically disastrous. In the underdeveloped conditions facin g

regimes of socialist orientation, the private sector continues to have an important role to play

6

in the provision of essential goods and services and in the accumulation of capital . Since the

state does not have the means to fulfil these functions itself, progressive regimes should not

proceed with hasty, ill-conceived nationalization programs . The African experience suggest s

that development is not only possible, but is often more impressive, in capitalist oriente d

states. In these circumstances where progressive change is so protracted and difficult, it doe s

not make sense for Soviet diplomacy to focus on the socialist-oriented regimes and to neglec t

those of other orientations . Indeed, the latter may have things to offer the Soviet Union i n

relations of mutual benefit .

Just as this view emphasizes the difficulties of socialist construction in Africa n

conditions, so too does it recognize the impediments to successful national liberation i n

southern Africa, given the continuing strength of indigenous forces opposed to the process o f

liberation. As a result, those subscribing to this tendency of articulation counsel caution an d

patience in the liberation struggle and again stress the need for broad fronts in that struggle .

They tend to be skeptical in the prevailing conditions of the utility of violence as a means o f

achieving liberation . The focus in explaining civil and interstate conflict in Africa lies on th e

role of indigenous nationalism, as well as ethnic and religious rivalries . By contrast, the role

of imperialism as a cause of conflict is played down .

Circumspection extends to the discussion of the role of the USSR in the region . This

tendency emphasizes the limited capacity of the USSR and the socialist camp to assist in th e

development process and fails to identify the "international socialist division of labor" as an

alternative to participation of the developing states in the international capitalist economy .

By way of consolation, perhaps, it is admitted that foreign private capital may play a positiv e

role in the development process, as can participation in the capitalist system of international

trade and investment . :Moreover, it also tends to play down the negative role played b y

Western states, the United States in particular, and to emphasize to a greater degree th e

existence of inter-imperialist contradictions . Thus, individual imperialist states are viewed a s

independent actors with agendas of their own . These agendas may or may not coincide with

the agendas of other imperialist states . Finally, this tendency recognizes the possibility o f

limited bilateral or multilateral cooperation with specific imperialist actors, in an effort t o

reduce the dangers of confrontation in the region and limit the damage done to relations

7

between the USSR and the West by disputes over Third World issues.

Both of these tendencies are in a sense ideal types . Few of the sources deal in a

comprehensive fashion with all of the issues raised above . Occasionally, individual authors

will combine aspects of both, evincing quite orthodox positions in some areas an d

unorthodox ones elsewhere, but such mixes are rare . The two paradigms are useful a s

indicators of theoretical perspectives consistent with revolutionary forceful activism on th e

one hand and quiescent moderation, if not withdrawal, on the other .

Moreover, intellectual history is seldom divided into neat and discrete periods .

Reality is, unfortunately, somewhat sloppy . When one moves from a period in which one

perspective is dominant to one in which its rival predominates, there is inevitably a degree o f

overlap between them . The interim likely displays considerable ambiguity and incoherence

in argumentation, both within specific articles and monographs (as authors combine ne w

unconventional perspectives with efforts to touch still pertinent ideological bases) an d

between them, as some individuals and institutions are less resistant to change than ar e

others .

The basic argument of this contribution is that we have moved since 1975 from th e

dominance of perspectives of the first activist tendency to increasing expression of views

consistent with the second . Both official and academic discourse reflect this transition . To

the extent that theory is a predictor of practice, or a reflection of it, this treatment of Sovie t

discussions suggests a retreat from the activism characteristic of the mid- and late 1970s .

This retreat may have resulted from many things : the increasing Soviet preoccupation wit h

domestic political and economic problems, the American military buildup of the early an d

mid-1980s and the associated renewal of American activism in the Third World, and/or th e

withdrawal of China from competition with the USSR over forces of liberation in the region .

But the growing sensitivity to the complexity and immalleability of the African environment

evident in the literature suggests that it resulted also from a growing accumulation o f

experience with the difficulties of pursuing objectives in this region . It is the product, i n

other words, of learning .

8

IL Activism in Theory : The Mid- and Late 1970 s

A Soviet scholar recently noted in conversation with me that as a result of th e

victories in Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, and later Nicaragua, he and his colleagues had

been carried away by a wave of enthusiasm for socialist-oriented states and this had blinde d

them to the great concrete difficulties faced by vanguard party regimes in the transition t o

socialism.' This optimistic assessment provided the theoretical basis for Soviet activism i n

the late 1970s .

A . The Vanguard Party and Socialist Orientatio n

This optimism is evident across the spectrum of issues under consideration here . In

domestic politics, highly positive assessments of emergent vanguard party, socialist-oriente d

regimes predominated . The vanguard party model -- a monopoly of power enjoyed by a

party of elite revolutionaries organized in accordance with the principles of democrati c

centralism and embracing scientific socialism -- was considered necessary to effectuate th e

transition to socialism via the path of socialist orientation . Broad national fronts, b y

contrast, were deemed inadequate to the task . 5 By implication, not only were previou s

efforts to secure objectives through cooperation with more traditional nationalist regime s

(such as those of Nasser's Egypt or Nkrumah's Ghana) less than promising, but it was als o

realistic and feasible to rely on more radical regimes espousing Marxism-Leninism in pursui t

of influence and position in Africa . Scientific socialism was an appropriate political form fo r

Africa. The emergence of vanguard party regimes was considered by many to be a

manifestation of a deeper transformation from the "national-democratic" stage of th e

transition to socialism, characterized by a broad coalition of indigenous forces with varyin g

degrees of commitment to socio-economic change, to the "people's democratic" one, i n

which power was concentrated in the hands of those social forces -- notably the proletaria t

and the peasantry -- more resolutely committed to profound transformation of society and th e

economy in the direction of socialism . ' The expansion in the number of vanguard part y

regimes in Africa (the Congo in 1969, Benin in 1976, Mozambique and then Angola in 1977 ,

and the stated intention of the Ethiopian military regime to do likewise) was considered

9

evidence of a weakening of the position of imperialism in Africa and a strengthening of th e

position of progressive forces on the continent .' Belief that the increasing emergence o f

these regimes reflected the basic trend of African politics was evidenced by Soviet assertion s

that the USSR's foreign policy in Africa was oriented toward, and dominated by, relation s

with the socialist-oriented states .' This optimism concerning the viability of the vanguar d

party model was based in part on a rather sanguine appraisal of the political capacities an d

inclinations of various social forces in Africa . In general, Soviet writers heavily criticized

any propensity to deny the relevance of class in the analysis of African society . Indeed, i t

was commonly argued that in the aftermath of independence, and as the struggle of Africa n

peoples shifted from the phase of national liberation to that of "national democracy," th e

class struggle deepened and became the dominant characteristic of political evolution i n

African society . ' In the analysis of this struggle, the national bourgeoisie (indigenou s

entrepreneurs in the retailing and manufacturing sectors) was on the whole written off as a

revolutionary force in the aftermath of political independence . 10 Meanwhile, comment on the

capacity of the working class to determine political events was mixed . Although many

continued to recognize the proletariat's numerical weakness and questionable level o f

consciousness," the dominant view appeared to be that as development proceeded, th e

political weight of this class was growing, its consciousness of class interest was increasing ,

and it was becoming the determining force in political development . 12 Many Soviet writer s

also evinced considerable enthusiasm about the ability of petit bourgeois and military group s

to overcome the social and political obstacles to the pursuit of the path of socialist orientatio n

in Africa. In the case of the military, numerous writers have pointed to the capacity of th e

Ethiopian officer corps, embodying the concerns and hopes of the majority of the people, t o

guide the process of social and political development in that country . Indeed, some argue d

that in the prevailing circumstances of extreme ethnic and political fragmentation, it was th e

only force capable of so doing . 13 This evaluation often extended to countries without a

socialist orientation as well . For example, when the Nigerian military was praised for it s

domestic and foreign policy initiatives .14 This stress on the potential of the military as a

progressive political force rested on a number of factors, among them the military's status a s

one of the few national institutions in which ethnic groups were integrated, its role as one of

1 0

the few modern and modernizing forces in African society, and its ability, through the office r

corps, to serve as an avenue of upward mobility for people of humble origin .

Arguably more important than the military were the so-called revolutionar y

democrats, comprised principally of radical intellectuals generally of "petit bourgeois" origi n

(the "srednye sloi") . This group was to lead the country along the path of socialis t

orientation -- from national liberation to national democracy (in which the principal task s

were anti-feudal, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist transformation), and ultimately to th e

stage of people's democracy . The argument concerning the capacity of this group -- i n

alliance with the working class and peasantry -- to lead the transition to socialism rested upo n

an optimistic belief that in conditions where the base was not in theory sufficiently mature to

stimulate movement in this direction, progress could be made through the manipulation of the

levers of state power by a steadfast, ideologically conscious and committed nonproletaria n

elite . 15 Such a judgment betrays considerable optimism about the capacity to implant stabl e

allied regimes in Africa, despite the underdeveloped character of African politics .

This optimism extends into the discussion of impediments to political development in

the direction of socialism on the continent . The most common perspective of the mid- an d

late 1970s was one in which the indigenous impediments to progress in the construction o f

the vanguard party, socialist-oriented state were played down in comparison to issues of class

and class struggle, the dynamics of which Soviet scholars claimed to understand and to b e

able to predict . One sees for example the argument with regard to Ethiopia that :

It is not without basis that Ethiopia was once called a "museum of peoples . "As a result of the revolution, the process of ethnic integration has received anew impulse and the basic tendency of development has been fully defined - -social factors (i .e ., class) are gaining the upper hand over ethnic and religiou sones . The great power policy of amharicization conducted by the emperor ha scome to an end .1 6

Elsewhere Soviet authors at this time argued that tribal divisions were gradually disappearin g

owing to the growing influence on intertribal social organizations such as trade unions, an d

were being replaced by deepening consciousness of class interests which transcended ethni c

division .

Nationalism, meanwhile, was seen as a dualistic force in African domestic politics .

1 1

During the phase of struggle for independence, it served to unify disparate political an d

social groups . In the aftermath of independence, it could be employed by progressiv e

revolutionary democratic regimes to further the process of national integration . But it often

turned into a chauvinistic extremism directed at other national groups within the state or a t

neighboring states (as in the case of Somalia), when bourgeois groups seeking to enhance

their newfound capacity to exploit their own populations appealed to chauvinistic sentiment s

to broaden their base of popular support . Nationalism in this sense diverted the attention o f

the masses and their leaders from the real character of the problems they faced in the

struggle for progress -- internal class struggle and external interference from imperialism .

Not to worry, however, as the process of social development proceeded, its influence would

gradually disappear, in the face of a growing Pan-African cultura

l consciousness.18. The Sources of Civil Conflict

The dismissal of factors such as ethnicity, religion, and nationalism as causes o f

internal conflicts in Africa leaves Soviet analysts with the necessity of developing an

alternative set of explanations . The dominant mode of accounting for civil conflict in Africa

was to blame it on internal class struggle (the efforts of indigenous feudal, patriarchal an d

bourgeois forces) fomented or fueled by interference on the part of imperialism . Both of

these forces shared the objective of preventing social progress . There was a degree o f

variation in Soviet characterizations of the sources of internal opposition . Some implied tha t

it grew out of indigenous class struggle and that, though it might benefit from external

interference, it was not created by imperialism . 19 Others stressed instead the agency o f

imperialism in creating, and not merely sustaining internal reaction and consequent conflict :

Numerous facts give a solid basis for declaring that the conflict in Angola, andthe worsening of the situation around it are the result of the crude interferenceof imperialist forces in the affairs of the Angolan people . . . It is a matter no tof some internal political or tribal problem, but one of open crude imperialis tinterference . 20

There was clearly a fair amount of heat in this discussion, notably (of all places) i n

Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn', a publication generally viewed as a rather boring and monolithi c

mouthpiece for propaganda directed at the outside world . Viktor Kudryavtsev responded to

1 2

views like that just quoted, by noting that :

It is not necessary to think that absolutely all internal African conflicts ar eassiduously provoked by imperialist policy . To judge them in this fashion i sto deliberately distract the peoples of Africa from attentive examination o fpurely internal sources of such conflict and to carry them all over either to th eplane of inter-imperialist conflict over raw materials or strategic position or, a sthe Maoists would have it, to the plane of the struggle between th esuperpowers for influence . 2 1

Four months later we see another writer in the same journal arguing that the policy of

imperialism and the activity of Peking "splitters" is precisely the reason for armed conflict i n

the Horn of Africa :

Elsewhere, although the enemies (!) of Angola seek to cast the developin gsituation in that country as one of internal civil war, in fact what is takin gplace there is an open imperialist aggression against a sovereign government . 2 7

These disagreements are intriguing and significant as portents for what has com e

since. But it ought to be emphasized that all of those engaged in this discussion -- whethe r

they accounted for the origins of civil conflict by reference to indigenous politics or t o

exogenous factors -- stressed the role of imperialism as a force of critical importance i n

sustaining and deepening processes of civil conflict . Indeed, one gets the impression tha t

Soviet authors in general -- whatever their views on the origins of civil conflict -- accepted

that absent the nefarious influence of imperialism, such disputes would evaporate .

Moreover, those who did emphasize the causal role of internal factors focused primarily o n

class struggle . National/ethnic problems were epiphenomenal manifestations of deeper clas s

conflicts . They were not autonomous factors in their own right .

C. Liberation in Southern Afric a

The issue of internal conflict leads naturally to that of liberation in southern Africa .

Given the temporal limits of this study, I examined comment on Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) ,

Namibia, and South Africa . It bears recalling that the mid-1970's, when this study begins ,

was a period of considerable success in the struggle against the last remnants of the colonia l

empires of Africa . With the fall of Mozambique, the capacity of the Smith regime i n

Rhodesia to hold on in the face of a mounting insurgency was increasingly a matter of

1 3

question . The growth of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa and th e

explosion of violence in Soweto in 1976 suggested to some that white rule in South Afric a

itself was weakening . In this historical context, it is not surprising that Soviet comment on

the issue of national liberation again was dominated in the mid- and late 1970s b y

considerable optimism on prospects for the struggle, and by a tendency to project th e

successful experience of armed struggle led by a conscious revolutionary movement i n

Angola onto the very different circumstances of South Africa and Namibia .

Along these lines, Yusuf Dadu of the South African Communist Party, writing in

Kommunist, asserted in 1976 that victories elsewhere in South Africa and notably in Angola

suggested that South Africa's hold on the region was weakening and that its capacity to hol d

the line against change in Namibia and South Africa itself was in question . 23 Change in the

correlation of forces in favor of world socialism, coupled with the quickening of the struggl e

on the subcontinent itself, doomed South Africa to defeat . 24 Events in Soweto merely

confirmed this evaluation . 25 Positive assessments extended to the liberation struggle then

underway in Rhodesia as well : "Neither military provocations, nor diplomatic contrivance s

will save the Rhodesian regime from its unavoidable collapse ."26

With regard to the means of struggle, Soviet writers generally took the view that

violence was a necessary tactic at this stage, given the continuing resistance of the Sout h

Africans and the Rhodesians (until 1979) to enter meaningful negotiations on a transfer of

power to the masses . 27 Compromise short of full dismantlement of the political status quo i n

Rhodesia, Namibia, and South Africa was deemed self-deluding . So too was any hope tha t

these regimes could, as a result of pressure upon them from within and without, embark o n

meaningful reforms . 28 They had to go, lock, stock, and barrel . The means of getting rid of

them was -- in part if not principally -- a revolutionary war of national liberation . The

principal agents of this revolutionary process were the vanguard movements -- SWAPO i n

Namibia, ZAPU in Rhodesia, and the alliance of the ANC and the SACP in South Africa . 29

There was little interest expressed in the construction of broader fronts . Potential allies, such

as the SASO-centered advocates of Black Consciousness, those willing to contemplate a n

internal solution in Namibia, and white moderate critics of the excesses of apartheid in South

Africa, were either ignored or subjected to criticism for ideological and political error . 30

1 4

Indeed, one detects in Soviet writing considerable discomfort with Black Consciousness i n

particular, for both theoretical and practical reasons . 3 1

One gets the impression that the Soviets believed that their chosen clients could

accomplish liberation themselves without the dilution of their revolutionary program tha t

would result from the search for allies among the less resolute . The post-liberation agend a

was the construction of vanguard party, socialist-oriented regimes and the pursuit of the non -

capitalist path of development already beginning in Angola and Mozambique . 32 Scorn of

prospects for negotiated settlement, indifference toward potential allies beyond selecte d

movements, rejection of partial solutions, coupled with skepticism about the capacity of white

regimes in the region to survive translates into revolutionary optimism.

D . Economic Developmen t

The mention of South Africa's post-liberation agenda brings us to the final set of

domestic issues to be considered -- those of economic development . Soviet though t

concerning economic development in Africa was, in the late 1970s, consistent with th e

optimism suggested by their treatment of political development and liberation in southern

Africa. The dominant view appeared to be that backwardness, or the incapacity to develop

fully, was not the result of inherent features of African society or Third World economies i n

general, but was rather the product of the colonial experience and continuing neocolonia l

exploitation . 33 The answer to the problem of development lay primarily in the dissociation o f

African economies from the world capitalist economy .' In this context, one might hav e

expected Soviet authors to claim that the USSR and the socialist camp (the "internationa l

socialist division of labor") could replace the international capital in the external relations o f

developing countries . And indeed, there was much comment stressing the importance to th e

African states of economic ties to the world socialist system . 35 The deepening of such

cooperation, based as it was on mutual benefit and equity rather than hierarchy and

exploitation, facilitated the process of development . 3 6

However, Soviet analysts generally avoided the more extreme claim . This

presumably reflects concern about resource scarcity even during the period of 1970 s

activism . It also explains to some degree the emergence of the discussion of national and

1 5

collective self-reliance examined briefly below . The unwillingness of the USSR t o

underwrite the process of development left open the question of just how these states were to

manage . Self-reliance was one answer. But self-reliance had the trappings of "thir d

pathism," and Third World exclusivity, both of which ran against Soviet political objective s

and ideological needs . Not surprisingly, given the conflicting tensions, the question of th e

role of the socialist camp as a motor for development was not adequately resolved at thi s

stage .

The internal strategy necessary for real development was that of the non-capitalis t

path, with a nationalized state sector taking the lead in investment and capital accumulation ,

and with severe restriction on the roles of both foreign capital and indigenous privat e

enterprise . 37 Economic activity was to be closely planned essentially along Soviet lines . The

Soviet Central Asian and Mongolian examples of non-capitalist development were considere d

applicable to the African situation . In general, prospects for rapid development along thi s

path were judged to be good . Although impediments to development along this path wer e

recognized, they tended to be depreciated at this stage. Moreover, the emphasis i n

discussion of such impediments lay on external (e.g., the structure of th e

imperialist-dominated international economic order) rather than internal (e .g ., traditional

agricultural practices) obstacles to development . 38 Where African traditions of production

were addressed, Soviet writers debated whether what they perceived to have been traditiona l

African communalism was an asset or liability in pursuing non-capitalist development, bu t

one gets little impression that the strength of tradition was seen as a significant problem fo r

states of socialist orientation . 3 9

This vision of the development process was highly bifurcated . The choice lay

between capitalism, dependence, and exploitation within the international capitalist economy -

- resulting in stagnation on the one hand, and non-capitalist policies leading to the transitio n

to socialism, cooperation with the socialist camp, and true development on the other . 40 Third

alternatives (e.g., various forms of "African socialism") were generally viewed with

skepticism . As noted above, Soviet writers were ambivalent about the idea of developmen t

through individual or collective self-reliance . 4 1

In other words, at this stage, Soviet authors tended to view underdevelopment and the

1 6

development process itself as intimately related to the global struggle between capitalism an d

socialism, and the Soviet socialist model to be applicable (indeed necessary) to that process .

They tended to underemphasize local sources of backwardness and impediments to

development . And despite the qualifications above, they appear to have overestimated th e

capacity of the socialist system to compensate for dissociation from international capital .

E. Inter-African Conflict

This brings us to a consideration of Soviet perspectives on the international relation s

of what Rotberg once called the African regional subsystem . In this section, I examine firs t

of all the processes, actors, and structures of inter-African relations . I then turn to the rol e

of external actors and the place of African events in the broader scheme of world politics .

Soviet comment on the sources and nature of conflict between African states at thi s

stage followed closely that concerning civil conflict within African societies . Sovie t

interpretation of the sources of conflict focused on the role of indigenous factors and that of

imperialism . As in the case of civil conflict, there was considerable attention paid to the

indigenous roots of tension . In the Horn, for example, much credit was given to the role o f

Somali national chauvinism in accounting for the conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia, the

principal conflict of the period involving two OAU member states . 42 However, nationalism

as a source of conflict was often attributed to the colonial legacy of artificial division o f

ethnic groups and ancestral homelands among different states creating numerous irredenta . 4 3

Moreover, it was the role of imperialism in fanning the flames of national particularism an d

African irredentism which turned these national contradictions into open conflict . 44 Indeed ,

the most frequently expressed view ignored the possibility that conflicts in Africa might hav e

important indigenous roots and attributed it purely and simply to imperialism . 45

F. Structures of Conflict Limitation -- The OA U

Given the attitudes toward collective self-reliance mentioned in the section on African

economic development, one might have expected Soviet scholars to be hostile to th e

Organization of African Unity as a regional structure inhibiting the establishment of soli d

bonds of influence with individual radical African states . However, Soviet analysts appeared

1 7

to assume that the natural perspective of African post-colonial states was anti-imperialist in

character and that this formed an objective basis for an alliance of a kind between the USS R

and the African community as a whole . The Soviet judgment of the OAU was that i t

embodied in some measure this anti-Western consensus . 46 This was particularly evident o f

the issues of national liberation in southern Africa and apartheid . 4 7

The eruption and perpetuation of conflicts between individual African states impeded

the consolidation and operationalization of this unified anti-imperialist African perspective .

Indeed this was why imperialism instigated and promoted such conflicts . This was also th e

reason for imperialist efforts to destroy the regional organization . 48 As such, despite

acknowledgement of the weakness of the OAU and the occasional ideological deviation s

(e .g ., Africa for the Africans) within it, Soviet analysts tended to view the organization an d

its impact in Africa favorably and to advocate its strengthening . 4 9

G . The Foreign Policies of African State s

Soviet treatment of the foreign policies of African states during the late 1970s was

somewhat at odds with their analysis of the progressive anti-imperialist orientation of th e

African community as a whole . It was clear that the focus of Soviet attention to Africa la y

on the states of socialist orientation -- Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Somalia (prior to

1978), Madagascar, Guinea, Benin, and the Congo . Judging from diplomatic instrument s

such as the treaties of friendship with Angola, Mozambique, and Ethiopia, join t

communiques, and scholarly and journalistic commentary, they were considered to b e

resolutely anti-imperialist, cognizant of the natural alliance between the USSR an d

themselves, and reliable supporters of Soviet policy initiatives elsewhere on issues such a s

disarmament, China, Soviet-American relations, and later Afghanistan, Kampuchea, th e

American arms buildup, and Afghanistan . It was assumed that this positive direction i n

policy stemmed naturally from their status as states of socialist orientation led by vanguard

parties . 50 The tenor of Soviet comment on these states suggests that the USSR expecte d

concrete and significant global benefits from the emergence of this coterie of ideologicall y

kindred states .

By contrast, there was less clarity of perspective in Soviet comment on states of

1 8

"capitalist orientation" (e .g., Nigeria, Zaire, Kenya, and the Ivory Coast) . Their continuing

dependence on the international capitalist economy, the links between the local bourgeoisi e

and international capital, and the antipopular character of their regimes often rendered the m

susceptible to manipulation by the imperialist states . 51 But there was little specific criticis m

of the foreign policies of these states . Indeed, not much was said about their international

behavior at all . One can, of course, take this silence -- when compared to the ample praise

of states of socialist orientation -- as tacit evidence of disapproval . But states with whom th e

USSR had reasonably well-established positive relationships such as Nigeria were sometime s

praised for their international roles . 52 Even in instances of states traditionally closely tied to

the West and hostile to the USSR, positive foreign policies were approvingly noted wher e

present . 5 3

The third category of African states here is that of "national democracy" -- thos e

states which were not capitalist in orientation but which had not bought into the vanguard -

party led, socialist orientation . In general, these states were seeking some kind of third path

in domestic and foreign policy between capitalism and orientation toward the West on th e

one hand and scientific socialism and orientation toward the socialist camp on the other . The

principal examples were Tanzania and Zambia, and, after 1979 and somewhat ambiguously ,

Zimbabwe. The tendency in Soviet writing in the 1970s was to deny the possibility of a

"third path" between capitalism and socialism and between imperialism and the "forces o f

progress" led by the USSR . 54 This was accompanied, as noted earlier, by a certai n

unhappiness with the advocacy by some of these actors of a collective economic self-reliance

of African or Third World states which could detach them from the necessity of choic e

between capitalism and socialism . 5 5

On the other hand, many aspects of the foreign policies of these states (rejection o f

apartheid, support for and sanctuary to national liberation movements struggling agains t

white rule in southern Africa, hostility to Western economic and political penetration o f

Africa) were deemed worthy of praise . 56 And although Soviet writers tended to criticiz e

conceptions of nonalignment conceived as true neutrality in the conflict between blocs, 57 on

the whole they argued that in objective terms nonalignment was a positive anti-imperialis t

force in global politics 'worthy of Soviet support .' This was consistent with a general Soviet

1 9

perspective on the international politics of Africa to the effect that events were leaning ver y

much in a direction favorable to the USSR . Solodovnikov, who -- prior to his ill-fate d

sojourn in Zambia as Soviet Ambassador -- was Gromyko's predecessor as Director of th e

Africa Institute, characterized the current period as one of the full liberation of Africa fro m

colonialism . 59 Others noted that the national liberation movement in the region was growin g

and deepening as it transferred its attention from political to social tasks, that the correlatio n

of forces in the region was moving in the direction of world socialism, and that the prestige

of the USSR in regional affairs was also expanding while the influence of imperialism was i n

decline . 6 0

There was one large fly in this ointment -- South Africa . During the mid- and late

1970s, South Africa was generally portrayed as operating hand in glove with Western

imperialism in the general attempt to maintain imperialist control over Africa, to prevent th e

deepening of the revolutionary process on the continent, and to facilitate capitalist access t o

African resources and markets . Although Soviet writers recognized that South Africa had

specific interests (e .g., the maintenance of a buffer between itself and the rest of Africa) ,

these were not deemed to conflict with the general interests of the West in the region . The

Western powers benefitted from the presence in the region of a powerful actor similarl y

opposed to the expansion of the positions of socialism and national liberation . South Africa

had an interest in close ties between itself and the NATO powers in order to secure th e

protection of the latter and access to Western arms supplies . In such circumstances, Sout h

Africa served as the strike force of imperialism in southern Africa and its major actions i n

foreign policy, such as the invasion of Angola in 1975, were taken on instruction from th e

imperialist powers . 61 Writers in Mezhdunarodnaya Zhizn' in particular evinced considerable

fascination for the role of South African-Israeli cooperation in the implementation o f

imperialist designs in Africa :

Using political, military, and economic levers, the leading Western powers ar edoing all they can to postpone the collapse of the last colonial racist bastions i nAfrica, to impose on free Africa a solution of problems in the south in whic hit would be possible to preserve the region their bridgehead and larder for ra wmaterials . Along with the RSA, Israel has recently attempted to play a role a san active force in the realization of these plans . . . The RSA is a bulwark o freaction in the south of Africa . Israel is well known as an ardent opponent of

20

revolutionary-liberation processes in the north of the continent . . . Thecongruence of the basic political and ideological positions of the two regime sis rooted in the commonality of the concepts of zionism and apartheid - -variants of racism . 62

Events in the region, however, were gradually weakening South Africa's position .

This resulted in some change in the policies of South Africa toward neighboring states . Yet

Vorster's purported interest in dialogue and detente in the aftermath of the collapse of th e

Portuguese position in the region were not motivated by any desire for genuine settlement o f

the basic issues dividing South Africa and its neighbors . Instead, South Africa's flirtation

with its neighbors was the diplomatic aspect of a strategy of continued hegemony . This was

complemented by efforts to strengthen the economic dependence of neighboring states, an d

by the increasingly threatening character of the South African military buildup . 63 In other

words, there was little reason to believe that this rogue state could be civilized . It was a

major threat to the independence of African states and only its removal could guarantee th e

full liberation of these states and the security of the movement's gains in Africa . Efforts at

compromise with it were doomed to failure .'

Nevertheless, as noted above, this diversification of South African efforts to sustai n

and strengthen its position was itself a product of the weakening of that position resultin g

from the defeats in Angola, the loss of its buffer, the worsening situation in Rhodesia, an d

the deterioration of the RSA's internal security typified by the Soweto uprising . Thus ,

despite recognition of the continuing danger to the liberation process from the RSA and it s

formidableness as a reactionary force in regional politics, the prognosis was basically

optimistic .

In short, the Soviet assessment of regional international relations was quite positive .

The influence of the Soviet Union was expanding, that of imperialism and local reactio n

contracting . Revolution in southern Africa was drawing toward its logical denouement ,

which would bring further gains to the USSR while strengthening already establishe d

positions .

2 1

H . The Roles of External Actor s

Soviet consideration of the role of external actors in regional politics follows from th e

essentially bifurcated globalist conception of African international relations noted above .

With regard to the Soviet role in the region, the discussion can be divided into three parts :

the Soviet role in the region as a whole, Soviet relations with liberated states, and Sovie t

support of the continuing struggle for national liberation .

In general terms, it was frequently posited that the rise of the world socialist syste m

and the growing strength of the USSR rendered it impossible for imperialism to succeed i n

perpetuating the colonial and neocolonial enslavement of Africa . The USSR impeded the

efforts of the Western states to hold on in Africa while supporting and defending African

interests in international fora, playing a key role, for example, in opposition to apartheid an d

in support of a more equitable international economic order . 65 As was noted earlier, th e

world socialist economic system provided an alternative for African states desiring to reduc e

their dependence on the international capitalist economy . Soviet economic assistance allowe d

African states to reduce their reliance on the imperialist powers for development assistance .

Soviet diplomatic support reduced African vulnerability to pressure from the West . 66 In

other words assistance from the socialist camp and the USSR provided a first line of defense

for Africa in the pursuit of independence and sovereignty . 67 Particular stress in Soviet polic y

was laid on relations with socialist-oriented countries . 68 The Soviet role with regard to these

states was multifaceted, including substantial economic project assistance, training of cadres ,

and the deepening of interparty relations . Soviet writers laid particular stress on the

importance of trading ties with the socialist camp as a substitute for continuing dependenc e

on the West . 69 Soviet economic assistance was crucial to success in the transition to non -

capitalist development . 70 Beyond this, they acknowledged an important Soviet role i n

defending these countries against aggression .71 In their discussions of Soviet treaties o f

friendship with Angola, Mozambique, and Ethiopia, Soviet analysts pointed in particular to

clauses in the treaties calling for mutual consultations in the event of a threat to the securit y

of either party . 7 2

The success of the national liberation revolutions in Angola and Mozambique brought

22

in their wake a series of expansive definitions of Soviet responsibilities with respect t o

revolutionary activity in the region . Soviet writers touted their country's principa l

responsibility for the success in Angola and, indirectly, in Mozambique, not merely for bein g

the major force in the shift in the international correlation of forces in favor of worl d

socialism, but also through direct assistance to the movements concerned . Military journal s

such as the Voenno-Istoricheskii Zhurnal were particularly insistent in this regard . 73

Occasionally they went so far as to recognize a direct Soviet military role in wars of thi s

type :

The influence of world socialism on the outcome of the armed struggle i nfavor of the freedom-loving African peoples is realized in a number of ways :the delivery of weapons, the transmission of the military experience of itsarmies, and, in especially critical circumstances, the direct forestalling of th eaggressor . 7 4

The recognition of the possibility of a direct role for Soviet forces in wars of nationa l

liberation goes well beyond traditional Soviet definitions of their role in conflicts of thi s

type,75 and is indicative of the view of at least some in the USSR that conditions in th e

region in the aftermath of Angola were such that the USSR could act with relative impunity

in furthering the region's revolutionary struggles against imperialism . Interestingly ,

however, Soviet military writers discussing specific regional conflicts where interventio n

might mean direct confrontation with sizable South African units were generally les s

forthcoming in their offers of support . 76 This suggests some awareness of continuin g

constraints on the use of force in regional conflicts . Authors in the civilian literature were

less specific in their discussions of the Soviet military role . 77 But they tended to be unfailin g

in their expressions of Soviet solidarity with the forces of national liberation and in the

articulation of a policy of substantial political and military support for such movements .

They agreed with their military colleagues on the significance of the Soviet role as a

determinant of success in struggles of this type . 78 The general impression one gets is one o f

enthusiasm for active multifaceted support of the national liberation revolution with littl e

direct comment on the dangers and possible costs of such a policy . This is paralleled by an

optimistic appraisal of the Soviet capacity to replace the West in economic relations wit h

African states, particularly those of socialist orientation, and the definition of an ambitious

23

Soviet role in economic development and diplomacy .

Little was said specifically about Soviet objectives in the region . But one can infer

from the incessant advocacy of ejecting imperialist influence from Africa and th e

corresponding concern noted earlier with the expansion of Soviet prestige that one Sovie t

objective in the region was to supplant US and Western European influence in Africa with its

own influence . There was even less indication from this literature of strategic or militar y

objectives in Soviet policy . Soviet interest in bases was of course denied . 79 One can hardly

expect any other perspective on the subject given the disinterested image that the USS R

sought to project . But it is possible that Soviet policymakers and analysts were little

interested in specific military assets such as bases . Much of sub-Saharan Africa was of little

strategic significance to the USSR (the exception presumably being the littoral of the Red Sea

and Bab-el-Mandeb) . And the experience of losing substantial onshore military facilities in

Egypt in 1972 and in Somalia in 1977 did little to encourage such preoccupations . Evidence

of the latter conclusion may be drawn from a 1979 article in Morskoi Sbornik, where the

author noted that :

The use of the world ocean for the organization of a system of mobile basin gof naval units, in the opinion of the US naval command, ensures the defense o fstrategically important regions and will not be vulnerable to "politica linstability" in regions where previous military bases were placed . 8 0

One may reasonably assume that this discussion of US naval policy is a surrogate reference ,

given the historical context in which it occurred.

The objectives of the United States in Africa, by contrast, were hardly disinterested .

The United States and the Western camp that it led were said to be motivated by an effort t o

maintain and strengthen political control of Africa. This was part of a global strategy of

struggle with, and containment of, the socialist camp and the forces of progress . It was also

motivated by a desire to secure stable access on favorable terms to the natural resources of

the African continent . 81 This required efforts to acquire military facilities in Africa, to

ensure the continued dependency of African states through their participation in the worl d

capitalist economy, to destabilize progressive regimes, and to resist the revolutionary proces s

in states dominated by reactionary forces closely allied to imperialism . 82 The instruments

24

available to the United States in this effort to hold back the forces of history included direc t

and indirect (via the World Bank and the IMF) economic pressure ; arms transfers an d

technical advice to regimes and movements sympathetic to Western positions ; intervention

where necessary in their behalf ; and the provocation and manipulation of conflicts stemmin g

from ethnic, religious, and national tensions . 83 These were supplemented by an incessant

anti-Soviet propaganda campaign focusing on a purported Soviet threat to Africa n

independence . Given the character of their interests in the region, there was little prospec t

for constructive American participation in efforts to improve its political and economi c

conditions . Western generated peace initiatives (e .g ., the Anglo-American initiatives o n

Zimbabwe and the Contact Group's efforts on Namibia) were characterized as hypocritica l

efforts to maintain imperialist hegemony at the expense of the true interests of the people s

concerned . 84

Little attention 'was given to the analysis of the autonomous roles of other Western

states (e .g ., France, Britain, Japan, and Israel) in regional affairs or to the potential

contradictions between their policies and interests and those of the United States . They were

considered component parts of a general imperialist strategy defined in large part by th e

United States . 85 As was noted earlier, this was true also of South Africa, which was seen no t

as an independent actor in regional politics, but as a loyal proxy and representative of

imperialist interests in the region .

In other words, the dominant interpretation of external involvement in African

regional affairs during the late 1970s was zero-sum in character, the united forces o f

socialism and national liberation being arrayed against those of internal reaction an d

imperialism. There was little if any structural basis for accommodation between the two .

The latter had to be defeated and rooted out . And defeat for one necessarily translated int o

victory for the other . As was seen earlier, the trend in this struggle was construed to b e

favorable to the forces of progress . There was little reason to expect this to change, give n

the shift in the global correlation of forces . As such, efforts at accommodation between the

two were not only unnecessary, but were pernicious .

This leads to the question of linkage . Clearly, events in Africa were linked to th e

global competition between imperialism and socialism in that they favored one side or the

25

other in the balance of forces between the two camps. However, Soviet writers rejected th e

concept of linkage as it was put forward by many American analysts . They denied tha t

rivalry in Africa impinged directly on the course of superpower relations at the center o f

world politics. Both superpowers had an interest in the pursuit of detente which existe d

independently of competition on the periphery. Both superpowers shared an interest in arm s

control, economic relations, and the stabilization of Europe. These interests were the basi s

of detente. They existed independently of competition on the periphery and persisted despit e

that competition . To put it another way, detente between states had nothing to do wit h

struggle between classes, of which Soviet support for progressive forces in the Third Worl d

was a part .

Efforts to argue, as Brzezinski suggested in his famous remark about detente lying

buried in the sands of the Ogaden, that the fate of detente rested on Soviet behavior i n

regional conflicts in the Third World, were viewed as spurious attempts by those opposed t o

detente to sabotage the process by rendering it hostage to unrelated events . Related efforts to

extend detente to cover revolutionary conflicts in Africa were similarly seen as a crudely

masked justification for counterrevolutionary intervention in African affairs . Indeed, far

from inhibiting revolutionary struggle in the Third World, detente facilitated it by restrainin g

the imperialists from forceful intervention . 86 Likewise, the victory of African struggle s

against racism, reaction, and imperialism strengthened detente by removing potential source s

of tension in world politics . It followed that Soviet support for such forces was not only no t

a violation of detente, but actually furthered the process of detente . Instead, Soviet writer s

maintained the opposite position -- that it was indeed not Soviet activity in Africa, bu t

Western support of reaction and racism which weakened the process of detente, and wa s

inconsistent with it . 87

The denial of the existence of a link between Soviet behavior in Africa and th e

general character of relations between the two superpowers may have reflected the actua l

Soviet world view at the time, or it may have been simply politically instrumental . In either

case, important implications follow from this position . In the former instance, it suggests a

tendency to underestimate the damage to their relations with the US, which might result fro m

forward anti-Western policies in Africa . In the latter, it implies a willingness to bear the

2 6

costs incurred as a consequence of such policies .

Soviet views on the potential for escalation stemming from superpower competition i n

Africa parallel those concerning linkage . There was during the late 1970s almost n o

expression of concern over the possibility of escalation from regional conflict to genera l

superpower confrontation in the literature surveyed . On those occasions where Soviet writers

discussed the question of escalation, it was generally to underline the dangers associated wit h

Western meddling, and not Soviet support for national liberation and social progress i n

Africa. Hence, in a 1978 article on the Horn, V . Grigor'ev noted that :

The activities of imperialism and reaction, arming and pushing Somali agains tEthiopia embrace the danger of internationalization of the conflict in the Hornand of transforming it into a hot spot of international tension . 8 8

The third external actor to receive considerable attention in the literature was China .

Opinion on Chinese motives in their African policy was divided . Some chose to emphasize

independent Chinese desires for "hegemony," for splitting the African countries away fro m

their natural ally, the USSR, or for provoking a confrontation between the United States an d

the USSR . 89 Others chose to view China as a conscious and willing collaborator in th e

imperialist effort to forestall the revolutionary process in Africa and to limit the Soviet rol e

in African affairs . 90 But there was considerable agreement on the objective consequences o f

Chinese activity. These were counterrevolutionary, strengthening the position of reactionar y

and imperialist forces in Africa and weakening that of the forces of progress . Hence, China

was an objective ally of imperialism in the region, a willing collaborator with South Africa ,

an active supporter of counterrevolutionary movements such as the FNLA in Angola, o f

reactionary regimes such as that of Zaire, and of Somali national chauvinism directed agains t

Ethiopia . 91 The vituperative and incessant quality of Soviet comment in this vein on Chin a

suggests that the activities of the PRC were a major preoccupation of Soviet analysts, an d

presumably policymakers, dealing with Africa .

The discussion of external actors leads naturally to that of the United Nations . Given

Soviet comment on the roles of the other four permanent members of the Security Council i n

Africa, one might have expected them to be skeptical if not uncomplimentary of tha t

organization's role in regional affairs at this stage as well . Yet to the limited extent that

27

Soviet commentators did address the role of the United Nations in regional affairs, thei r

evaluation was generally positive . Soviet writers praised the constructive role of the United

Nations in the process of decolonization, its position on apartheid, its efforts to resolve th e

Namibia question, and its support for SWAPO, the ANC, and the Patriotic Front in

Zimbabwe . 92 This presumably reflects the salience of the role of the General Assembly on

these issues, the dominance of the Assembly by Third World states committed to what th e

Soviets construed to be constructive positions on these issues, and the prominent role playe d

by the USSR itself in assembly deliberations on these issues .

To summarize, Soviet analysts viewed the international politics of the region as a

zero-sum game. The imperialist powers, led by the United States, were engaged in a

systematic effort to resist the process of liberation on the continent and to retain thei r

neocolonial hold on Africa . The manipulation of regional conflict was a major instrument i n

this effort to dominate . China joined them in this cause. The most important implication o f

this perspective was that the imperialist powers and their proxies had no interest in genuin e

cooperation in the management and resolution of conflicts . Given the inexorable rise of th e

forces of liberation, moreover, there was no point in such negotiation . The USSR, as th e

leading force in the world revolution, had an obligation to assist the process of liberation ,

rather than to cooperate in stifling it through compromise . Thus, in this realm as well ,

Soviet thinking with respect to politics in Africa was militant and confrontational .

III. Modifications

This activist, optimistic perspective on African politics and international relations wa s

not unanimously endorsed even during its heyday in 1976-77 . As time passed and Soviet

experts became more aware of the difficulties of attaining maximal objectives (socialis t

revolution and substantial durable influence in Africa), increasingly complex, ideologicall y

flexible, skeptical and pessimistic interpretations of African affairs came to compete mor e

strongly with the orthodoxy of the mid-1970s . By the end of the period under consideration ,

many of the more orthodox historicist interpretations of African politics had largel y

disappeared .

2 8

A . The Vanguard Party and Socialist Orientatio n

Several basic propositions identified in the previous section concerning class, socialis t

orientation, and the vanguard party came under increasing fire toward the end of the 1970 s

and in the early 1980s . Soviet writers to an increasing degree recognized the multi -

structured character of African society as well as the continuing strength of traditional socia l

structures and their ideological reflections (e .g., tribalism and, with some qualification ,

religion) . 93 These operated as substantial impediments to progress along the path of socialis t

orientation . 94 This growing stress on the role of traditional factors in African political

development paralleled a larger rediscovery of the significance of ethnic and religiou s

tradition in politics as a whole in the Soviet literature which gathered force throughout th e

1980s . 95 By 1987, Georgii Mirskii was asserting that :

Years passed before the great weight of traditional factors was properlyassessed . Nonclass social institutions and phenomena (such as tribalism an ddeeply rooted divisions of Asian and African societies along ethnic, religious ,cast, and clan lines) in the last analysis take the form of an exceptionall ydurable system of patronage-clientelistic links, concealing or pushing into th ebackground class contradictions . 96

In the limited modern sector, they grew increasingly aware of the strength and vitality

of capitalist as opposed to socialist or protosocialist structures . 97 The weakness of

progressive sectors of the population (e .g., the proletariat and intelligentsia) was underlined ,

as was their vulnerability to distraction by various reactionary ideologies such as tribalis m

and national chauvinism . As Kosukhin and Belikov put it with regard to the working class :

Analyzing the factors impeding the proletariat from realizing their vanguar drole in the current period, communists emphasize the incompleteness of thei rformation as a class, their insufficient weight in the population, the presence ofmany transitional groups, the dispersal of a significant component of the clas sinto small and handicraft industries, their weak political organization, th eisolation from the masses and integration into the ruling regimes' bureaucrati capparatus of parts of the trade union leadership, the influence of peti tbourgeois ideology, social reformist illusions, religion, and "patriarchal "survivals on the workers . 9 8

The tendency of petit bourgeois dominated, revolutionary regimes toward bureaucratizatio n

was also stressed . 99

29

Even quite early in the period under consideration, enthusiasts on the military's rol e

in African politics were criticized for their uncritical optimism and their inattention to th e

group's potentially reactionary and essentially undemocratic character . 100 Much subsequen t

discussion of the military, particularly that in non socialist-oriented states such as Nigeria ,

displayed far greater ambivalence about the role of this group, stressing its contradictory rol e

in domestic politics and the partiality of its commitment to progress . 101 In comment on the