Information Asymmetries and Incentive Problems in Microcredit Markets Rachael Meager The University of Melbourne October 2011

Information Asymmetries and Incentive Problems in Microcredit Markets

Sep 12, 2014

Welcome message from author

This document is posted to help you gain knowledge. Please leave a comment to let me know what you think about it! Share it to your friends and learn new things together.

Transcript

Information Asymmetries and Incentive Problems in Microcredit Markets

Rachael Meager The University of Melbourne

October 2011

What is Microcredit? • Microcredit Institutions (MCIs) themselves describe it as: “small loans given to low-

income entrepreneurs who lack the ability to receive loans from a formal bank.” (Wokai.com)

• Usually involves loans from 50USD - 1000USD denominated in local currency, interest rates typically range from 20-40%. Official intention is usually a business loan.

• An MCI may be a charitable NGO seeking only to break even (if that), or a firm or bank seeking to make a profit. Funding sources: donations, loans from commercial banks, or investment by special international funds called Microfinance Investment Vehicles. Some MCIs are in fact simply lines of credit extended by a commercial bank.

• The global microcredit market is expanding rapidly: From 16.9 million clients (9 million earning under $1/day) in 1997 to 154.8 million clients (106.6 million earning under $1/day) in 2007. (Morduch and Armendariz, 2010).

Loan officer in a branch of Ahon Sa Hirap in the Phillippines. Note the 25% interest rate. Photograph: Peter Bardsley.

Does Microcredit Work?

That depends on how you define “work”…

• Does microcredit reduce poverty? Evidence is mixed and data is scarce, but on balance it seems that there is no short run reduction in poverty (Banerjee, Duflo et al, 2010). However, no randomised controlled trials have been done over the long term.

• Does microcredit improve the welfare of the poor? Almost certainly. At the very least, one major difficulty of extreme poverty is income irregularity: access to credit is absolutely vital to smooth consumption and enable purchase consumer durables (Collins et al 2010). Especially good because in general the financial management options available to the poor are insufficient.

• This is not the stated intention of most MCIs, which was to provide business loans, so some people (mostly journalists) see the fact that in some areas up to 30% of microloans are used for consumption as evidence that microcredit doesn’t work. (Boudreaux and Cowen 2008)

Does Microcredit Work?

• However, if by “work” we mean “efficiently allocate funds to those who are best able to make productive use of them, producing a functional market for lending and borrowing” the answer is…we don’t know.

• To the surprise of many (journalists again) microcredit markets are prone to the same information problems and perverse incentives that pervade conventional credit markets. (Yes, even if you’re a kind-hearted NGO).

• But microcredit markets use different mechanisms to combat the problems (both due to their clientele and the regulatory environment). Those mechanisms might create different outcomes than those of a conventional credit market – in fact they probably do.

• Famously high repayment rates (Grameen claimed 96% last month) but the mixed evidence on poverty reduction is unfortunate… as is the market’s apparent propensity for crises.

Information Problems & Incentive Issues

• If microcredit is to “work”, in the sense of producing a functional credit market, several problems inherent to credit markets must be overcome. It is useful to analyse the current operations and conventions in microcredit in terms of these issues.

• In fact, the problems may indeed be worse than in “conventional” credit markets because of the weak regulatory and legal environment, poor governance, inability of impoverished borrowers to protect themselves from shocks, etc.

• Information and incentive problems occur both on the borrower side and on the lender side.

• We will examine the issue of intermediary information and incentive issues in the lender side of the analysis.

The Borrower Side

• Two major information asymmetries pervade microcredit (and all credit) markets on the borrower side.

• Adverse Selection – ex-ante hidden information problem, usually in the form of unobservable differences across borrowers and their projects. This may be differences in risk level of project, or differences in average return of project, or a combination of both.

• Similarly to the Akerlof “market for lemons” problem, the presence of the low types drives up the interest rates in the market which has a disproportionately negative effect on the high types.

• However, in the case of a credit market, here may be a natural upper bound on interest rates due to the benefits of “credit rationing” to the lender/intermediary (Stiglitz and Weiss 1981).

The Borrower Side

• Moral Hazard – ex-post hidden action problem, usually in the form of unobservable actions borrowers may take contrary to the aims of the lender (whose aim, unsurprisingly, is “repayment”).

• This may include choices over effort levels: if the borrower only has a limited “exposure” in the case of failure, she has insufficient incentive to put in effort to ensure success.

• Or this can include choices over reporting of outcomes: a borrower whose project is successful may be able to conceal success from the lender, and engage in a strategic default. This occurs if the penalty for default is less costly to the borrower than repayment.

• If MH cannot be mitigated at least some of the time, loans simply will not be offered and there will be no market.

Corrective Mechanisms

Monitoring

• Monitoring seems like the most obvious solution – to fix AS you would monitor ex-ante, to fix MH you would monitor ex-post.

• However, it is also an extraordinarily costly solution: you either have to expend your own time monitoring or pay someone to do it for you (which creates a new incentive problem!). It is very rare that this is cost-effective for the lender.

• Even if it were cost effective, lenders may not have the skills or local knowledge to competently monitor all their borrowers’ projects

• Costs/knowledge problems can be somewhat reduced by employing a local as your loan officer, but this rarely solves the problem completely.

Corrective Mechanisms

Physical Collateral

• The promise of physical assets to be exchanged in the case of default. This is the traditional solution to the incentive compatibility problem that arises from MH. Loan contract is essentially “You repay your loan or I will take your stuff”. This has been used since Roman Empire, probably earlier.

• This also mitigates AS! Why? Because being willing to put up physical assets as collateral is a costly signal – the borrower must believe he has a good chance of being able to repay if he will “bet” the collateral on it.

• Physical collateral is not emphasised by many MCIs. Several major microlenders such as the Grameen Bank, FINCA, Badan Kredit Desa and Bancosol do not require it. However some do use it: Bank Rakyat Indonesia and Agricultural Bank of Mongolia.

Corrective Mechanisms

Social Collateral • Social collateral exists where a borrower can use his community relationships or social

ties to guarantee a loan. This is widely used by MCIs.

• This mitigates MH as long as the community or the individuals to whom a borrower links him or herself have the ability to punish failure to repay a loan, be this imposing a physical cost (violence), a financial cost (property extraction) a social cost (ostracism) or a moral cost (guilt).

• Quite uniquely, social collateral also induces third-party monitoring (by the community).

• It is no coincidence that many MCIs try to make themselves part of the fabric of the society/community! For example many offer playgroup or creche services during loan meetings. The deeper the MCI can embed itself in the community the more costly is default for a borrower, even just to the extent that her default is more obvious to others and she thus loses “face” (social capital).

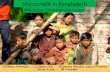

Playgroup outside a branch of Ahon Sa Hirap, a Grameen-style MCI, in the Philippines. Photograph: Peter Bardsley.

Corrective Mechanisms

Group Lending – a special case of social collateral

• The most famous mechanism used by Grameen: customers deal with the bank in groups (5-6 people), and loans are given successively to members. All members are responsible for repayments – all are blacklisted if one member defaults.

• Operates as a screening device to mitigate AS: locals have good information about each other’s “types”, and bad types will not be accepted into groups with good types.

• Operates as an incentive mechanism against MH as other group members can effectively monitor the borrower for the MCI, and furthermore, they can punish a defaulting group member using social sanctions. Widespread (anecdotal) evidence that this occurs.

• This particular model is less popular than it used to be, even with Grameen – concerns that it was “too harsh” to ban all group members for one default.

Corrective Mechanisms Reputational Collateral

• The MCI offers a borrower a loan: if she defaults, she is blacklisted from borrowing forever. May also be combined with escalation of loan sizes, so that borrowers cannot get the loan sizes they want without first building up a track record.

• Mitigates AS: it screens out borrowers who are poor money managers (well, eventually – not immediately, they can take that first loan!)

• Acts as an incentive against MH: The threat of termination can be thought of as threat to strip the borrower of the “option” to borrow again – thus, a good reputation with the bank is an asset the borrower will lose if she defaults.

• This is distinct from broader reputation mechanisms, such as credit ratings (“general” reputational collateral). It has more in common with relationship banking .

• Issues with this mechanism: competition among lenders may weaken its power (by lowering the value of holding a reputational asset with any one bank).

Corrective Mechanisms

Focus on women

• Many MCIs claim that their high repayment rates are due to their focus on women borrowers. 97% of Grameen’s clients in 2010 were women, and other MCIs like ProMujer and Kenyan Woman’s Finance Trust only lend to women.

• Belief is that among the global poor, women are better at managing money because they have to run households and they are “more long term” oriented. In some sense they are claiming this gets around an aspect of the AS problem.

• Small problem: there’s no evidence for this belief.

• Nevertheless, the microcredit industry does not appear to be letting go of this.

Corrective Mechanisms

Other Incentive Schemes!

• Many MCIs have repayment schedules that begin almost immediately, and demand weekly repayment. The aim here is to screen out borrowers who are poor money managers and would thus be unable to make the weekly payments – this can be thought of as a kind of monitoring.

• In some cases, banks offer clients special discounts for fast repayment. Bank Rakyat Indonesia sometimes offers 25% discount if you pay your loan back before a specified time.

• Some banks – usually those with state ties or support - can garnish borrower wages in the case of default. This is a form of physical collateral that provides almost full insurance for the bank too. The Agricultural Bank of Mongolia has a scheme like this.

The Lender Side

• On the lender side, again microcredit markets have similar information problems and incentive issues to those of conventional credit markets.

• Intermediary Moral Hazard – the goals of the intermediary, the MCI in this case, differ from the goals of the lender/investor, and the MCI can take hidden action ex-post contracting. (This should sound very familiar, GFC anyone?).

• Employee Moral Hazard – the goals of the employees of the MCI differ from the goals of the MCI itself, and the employees can take hidden action. Usually the concern here is over the quality of the loans made: the MCI (and investors) want a good quality loan with a low likelihood of delinquency or default, but this is not necessarily the loan officer’s goal.

• These things would tend to compound each other: the investor or donor has his goals, but the MCI may not share them, and then the employee adds another level of information asymmetry and incentive issues.

Corrective Mechanisms: Intermediaries

Monitoring

• Possible with Microfinance Investment Vehicles. MIVs are big enough and presumably have the expertise to monitor both ex-ante and ex-post. (Microfinance assets held by MIVs grew from US$705 million in 2005 to US$4.2 billion in 2009 .)

• However most MCIs actually source funds from a variety of places, most of which cannot monitor the MCIs as they are in other cities or countries.

Reputational Collateral

• General reputational collateral, in the form of an MCI rating which can be accessed by donors/investors : rating agencies include CRISIL and MicroRate.

• Think of the rating as an asset that has value to the MCI: this mitigates MH by providing an incentive to behave well. Possible issue: current ratings reward MCIs with social goals over those without, which is not necessarily correlated to making good quality loans.

Corrective Mechanisms: Employees

Contract Design

• Loan officers are often partially remunerated based on the performance of their loan portfolios. This is textbook contract theory: you must tie the agent’s profit to her performance!

• However, this has to be designed very carefully: it is a bad idea to reward loan officers for making many loans, or for making big loans. The goal is to make good quality loans, with a low chance of default – therefore, remuneration should be tied to the delinquency/default rate of an employee’s loan portfolio.

• Surprising degree of sophistication in how MCIs have set these up. Many do tie loan officer pay to portfolio default rates in some way! Eg. Crediamigo, Bank Rakyat Indonesia, Kazakhstan Small Business Program and the Agricultural Bank of Mongolia.

Microcredit Crises

• What do we mean by a microcredit crisis?

• Loosely, we mean that default rates become so high in an area that a number of MCIs either are, or are at serious risk of becoming, forced to cease operations in that area due to insolvency.

• However, confusion abounds over how high default rates have to be before these shut-downs start to occur – it’s not clear how much MCIs can absorb, and we have embarrassingly bad data on defaults and delinquencies in most cases.

• Further confusion arises because the press doesn’t agree with our definition of a microcredit crisis and prefers to use the term to refer to any old problem in a microcredit market.

Examples of Microcredit Crises

• Bolivia (1999) – a genuine crisis seems to have occurred organically here.

• Bosnia (2009)– a smaller crisis seems to have occurred organically here.

• Nicaragua (2009)– this was a completely government-created crisis. Amid growing popularity of “No Pago” movement, the government publically announced that it would support borrowers if they refused to repay. The borrowers promptly refused to repay. (Surprise!).

• Andhra Pradesh (2009-2010) – unclear what happened here, as data is extremely sketchy. After public outcry about supposed microcredit-related suicides, government stepped in and used legislation to shut down a lot of microcredit operations. Not clear whether the defaults started before this, or after this. What public outcry? “It’s worth noting that some of the loudest complaints about MFIs have come from the Andhra Pradesh state agency that oversees and promotes the SHG program.” Justin Olivier, CGAP.

Supposed Causes

“Greedy profit-seeking banks were lending too much money , setting usuriously high interest rates, and lending to people who couldn’t repay.”

• That doesn’t sound like something I would do if I wanted to make a profit. Proponents of this theory must explain why a bank would intentionally do this.

• Unfortunately for this theory, markets filled with profit-seeking MCIs don’t appear to produce more crises than those filled with saintly NGO MCIs. Proponents of this theory need to explain this. Indonesia and Brazil both have a high proportion of commercial MCIs but neither have experienced crises.

• Furthermore, even if MCIs were charging “unfair” interest rates, that’s no reason to get rid of them in and of itself, nor does it seem to be a plausible cause for a crisis (or suicides). Shashi Tharoor: “Traditional moneylenders are the only alternative, and they extort far more than 30 per cent a year – often at the point of a knife, or worse.” So where’s the moneylender crisis?

Supposed Causes “Bad loan officers”

• A definite possibility: if loan officers are remunerated based on size or number of loans made, they might well make bad quality loans.

• No major study has been done as yet linking microcredit crises to banks that have bad incentive schemes for their employees.

“Unduly harsh penalties for default”

• Not clear why having harsher penalties for default would make people default more. Possibly there is a strange mechanism at work here: if penalty for default is negative infinity, then if I know for sure I have to default, my only goal is to delay that event. So maybe I should take out other loans to repay that loan and spin this out as long as possible.

• Unlikely however that MCI mechanisms have effectively implemented a penalty that borrowers perceive as minus infinity. MCIs cannot legally murder you if you default.

What really causes microcredit crises?

• It often seems to involve overlending, that is, lending to people who can’t repay. It also often seems to involve a number of MCIs – crisis does not tend to occur under monopolies – so possibly there is a competition dimension to the mechanism causing crises.

• Could it be that the unconventional mechanisms employed to mitigate information asymmetries just are not working properly in these situations – or worse, are they creating bad equilibria?

• Currently there is lots of talk but very little technical theory in this area. Good work has been done by Morduch, Armendariz, Rei, Sjostrom, but we need more.

• If there really is a systemic problem with the mechanisms used in microcredit markets then we can successfully intervene to prevent crises. But we don’t know that’s the case.

Key Ideas • Microcredit markets are just as prone to information problems and incentive

issues as conventional credit markets – and they often operate in very poor legal environments. Even being a benevolent NGO cannot protect you from powerful perverse incentives.

• MCIs often use unconventional mechanisms to mitigate these problems on the borrower side, and as yet we don’t have a strong technical understanding of these mechanisms and how they might interact with each other.

• We have relatively poor information about what is actually going on in microcredit markets, especially during crises.

• We need to generate better understanding of microcredit markets – so far government policy seems to exacerbate rather than fix the problems, and there is not enough rigorous analysis being done of serious issues like microcredit crises.

Related Documents