-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

1/58

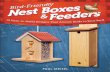

Bird-Friendly

Building

Design

Bird-Friendly

Building

Design

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

2/58

The area o glass on a aade is the strongest predictor o threat to birds. The aade o SauerbruchHuttons Brandhorst Museum in Munich is a brilliant example o the creative use o non-glass materials.Photos: Tony Brady (let), Anton Schedlbauer (background)

(Front cover) Boris Penas Public Health Oce building in Mallorca, Spain, sports a galvanized, electro-used steelaade. Photo courtesy o Boris Pena

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

3/58

3Bird-Friendly Building Design

Table of Contents

Executive Summary 5

Introduction 6

Why Birds Matter 7

The Legal Landscape 7

Glass: The Invisible Threat 7

Lighting: Exacerbating the Threat 7

Birds and the Built Environment 8

Impact o Collisions on Bird Populations 8

The Impact o Trends in Modern Architecture 8

Dening Whats Good For Birds 9

ABCs Bird-Friendly Building Standards 9

Problem: Glass 10Properties o Glass 11

Reections 11

Transparency 11

Black Hole or Passage Efect 11

Factors Afecting Rates o Bird Collisions 11

at a Particular Location

Building Design 12

Type o Glass 12

Building Size 12

Building Orientation and Siting 12Design Traps 12

Reected Vegetation 14

Green Roos and Walls 14

Local Conditions 14

Lighting 14

Solutions: Glass 16

Facades, netting, screens, grilles, 18

shutters, exterior shadesAwnings and Overhangs 20

UV Patterned Glass 20

Angled Glass 20

Patterns on Glass 22

Opaque and Translucent Glass 24

Shades, Blinds, and Curtains 26

Window Films 26

Temporary Solutions 26

Decals 26

Problem: Lighting 28

Beacon Efect and Urban Glow 29

Solutions: Lighting Design 30

Lights Out Programs 31

Solutions: Legislation 34

Appendix I: The Science of Bird Collisions 37

Magnitude o Collision Deaths 37

Patterns o Mortality 37

Avian Vision and Collisions 38

Avian Orientation and the Earths Magnetic Field 38

Birds and Light Pollution 39

Light Color and Avian Orientation 40

Weather Impact on Collisions 40

Landscaping and Vegetation 40

Research: Deterring Collisions 41

Appendix II: Bird Migration 44

Diurnal Migrants 45

Nocturnal Migrants 46

Local movements 47

Appendix III: Evaluating Collision Problems 48

A Building Owners Toolkit

Seasonal Timing 49

Diurnal Timing 49

Weather 49

Location 50

Local Bird Populations 50

Research 51

Appendix IV: Example Policy 52

References 54

Acknowledgments 57

Disclaimer 57

Ruby-throated Hummingbird: Greg Lavaty

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

4/58

4 Bird-Friendly Building Design

41 Cooper Square in New York City, by Morphosis Architects, eatures a skin o perorated steel panelsronting a glass/aluminum window wall. The panels reduce heat gain in summer and add insulat ion

in winter while also making the building saer or birds. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Issues o cost prompted Hariri Pontarini Architects, in a joint venture with Robbie/

Young + Wright Architects, to revise a planned glass and limestone aade on theSchool o Pharmacy building at the University o Waterloo, Canada. The new designincorporates watercolors o medicinal plants as photo murals. Photo: Anne H. Cheung

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

5/58

5Bird-Friendly Building Design

Collision with glass is the single biggest known killer o birds in the United States, claiming hundreds o millions or more lives

each year. Unlike some sources o mortality that predominantly kill weaker individuals, there is no distinction among victims

o glass. Because glass is equally dangerous or strong, healthy, breeding adults, it can have a particularly serious impact onpopulations.

Bird kills at buildings occur across the United States. We know more about mortality patterns in cities, because that is where

most monitoring takes place, but virtually any building with glass poses a threat wherever it is. The dead birds documented by

monitoring programs or turned in to museums are only a raction o the birds actually killed. The magnitude o this problem

can be discouraging, but there are solutions i people can be convinced to adopt them.

The push to make buildings greener has ironically increased bird mortality because it has promoted greater use o glass

or energy conservation, but green buildings dont have to kill birds. Constructing bird-riendly buildings and eliminating

the worst existing threats requires imaginative design and recognition that not only do birds have a right to exist, but their

continued existence is a value to humanity.

New construction can incorporate bird-riendly design strategies rom the beginning. However, there are many ways to

reduce mortality rom existing buildings, with more solutions being developed all the time. Because the science is constantly

evolving, and because we will always wish or more inormation than we have, the temptation is to postpone action in

the hope that a panacea is just round the corner, but we cant wait to act. We have the tools and the strategies to make a

dierence now. Architects, designers, city planners, and legislators are key to solving this problem. They not only have access

to the latest building construction materials and concepts, they are also thought leaders and trend setters in the way we build

our communities and prioritize building design issues.

This publication, produced by American Bird Conservancy (ABC), and built upon the pioneering work o the NYC AudubonSociety, aims to provide planners, architects, designers, bird advocates, local authorities, and the general public with a clear

understanding o the nature and magnitude o the threat glass poses to birds. This edition includes a review o the science

behind available solutions, examples o how those solutions can be applied to new construction and existing buildings, and

an explanation o what inormation is still needed. We hope it will spur individuals, businesses, communities, and governments

to address this issue and make their buildings sae or birds.

ABCs Collisions Program works at the national level to reduce bird mortality by coordinating with local organizations,

developing educational programs and tools, conducting research, developing centralized resources, and generating

awareness o the problem.

Executive Summary

A bird, probably a dove, hit the window o an Indianahome hard enough to leave this ghostly image on theglass. Photo: David Fancher

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

6/58

Introduction

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

7/58

7Bird-Friendly Building Design

Why Birds MatterFor many people birds and nature have intrin-

sic worth. Birds have been important to humans

throughout history, oten used to symbolize cultural

values such as peace, reedom, and delity.

In addition to the pleasure they can bring to people,we depend on them or critical ecological unctions.

Birds consume vast quantities o insects, and control

rodent populations, reducing damage to crops and

orests, and helping limit the transmission o diseas-

es such as West Nile virus, dengue ever, and malaria.

Birds play a vital role in regenerating habitats by pol-

linating plants and dispersing seeds.

Birds are also a vast economic resource. According

to the U.S. Fish and Wildlie Service, bird watching isone o the astest growing leisure activities in North

America, and a multi-billion-dollar industry.

The Legal LandscapeAt the start o the 20th Century, ollowing the

extinction o the Passenger Pigeon and the near

extinction o other bird species due to unregulated

hunting, laws were passed to protect bird popula-

tions. Among them was the Migratory Bird Treaty

Act (MBTA), which made it illegal to kill a migratorybird without a permit. The scope o this law, which

is still in eect today, extends beyond hunting, such

that anyone causing the death o a migratory bird,

even i unintentionally, can be prosecuted i that

death is deemed to have been oreseeable. This

may include bird deaths due to collisions with glass,

though there have yet to be any prosecutions in the

United States or such incidents. Violations o the

(Opposite) The White-throated Sparrow is the most requent victim ocollisions reported by urban monitoring programs. Photo: Robert Royse

The hummingbird habit o trap-lining fying quickly rom one eedingspot to another causes collisions when fowers or eeders are refected inglass. Photo: Terry Sohl

MBTA can result in nes o up to $500 per incident

and up to six months in prison.

The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (originally

the Bald Eagle Protection Act o 1940), the Endan-

gered Species Act (1973), and the Wild Bird Conser-

vation Act (1992) provide urther protections orbirds that may be relevant to building collisions.

Recent legislation, primarily at the city and state

level, has addressed the problem o mortality rom

building collisions and light pollution. Cook County,

Illinois, San Francisco, Caliornia, Toronto, Canada,

and the State o Minnesota have all passed laws or

ordinances aimed at reducing bird kills, while other

authorities have pushed or voluntary measures.

The International Dark Skies Foundation, an environ-mental organization whose mission is to preserve

and protect the nighttime environment now ac-

tively supports legislation designed to protect birds

by curbing light emissions.

Glass: The Invisible ThreatGlass can be invisible to both birds and humans.

Humans learn to see glass through a combination

o experience (how many o us at some time in our

lives have walked into a glass door or seen some-body do so?), visual cues, and expectation, but birds

are unable to use these signals. Most birds rst en-

counter with glass is atal when they collide with it

at ull speed.

No one knows exactly how many birds are killed by

glass the problem exists on too great a scale, both

in terms o geography and quantity but estimates

range rom 100 million to one billion birds each year

in the United States. Despite the enormity o the

problem, however, currently available solutions can

reduce bird mortality while retaining the advantages

that glass oers as a construction material, without

sacricing architectural standards.

Lighting: Exacerbating the ThreatThe problem o bird collisions with glass is greatly

exacerbated by ar ticial light. Light escaping rom

building interiors or rom exterior xtures can attract

birds, particularly during migration on oggy nights

or when the cloud base is low. Strong beams o light

can cause birds to circle in conusion and collide

with structures, each other, or even the ground. Oth-

ers may simply land in lighted areas and must then

navigate an urban environment rie with other dan-

gers, including more glass.

Birds and the Built EnvironmentHumans rst began using glass in Egypt, around

3500 BCE. Glass blowing, invented by the Romans

in the early First Century CE, greatly increased the

ways glass could be used, including the rst use o

crude glass windows. Although the Crystal Palace in

London, England, erected in 1851, is considered by

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

8/58

8 Bird-Friendly Building Design

architects to mark the beginning o the use o glass

as a structural element, the invention o foat glass in

the 1950s allowed mass production o modern win-

dows. In the 1980s development o new production

and construction technologies culminated in todays

glass skyscrapers.

Sprawling land-use patterns and intensied urban-

ization degrade the quality and quantity o bird

habitat across the globe. Cities and towns encroach

on riverbanks and shorelines. Suburbs, arms, and

recreation areas increasingly inringe upon wetlands

and woodlands. Some bird species simply abandon

disturbed habitat. For species that can tolerate dis-

turbance, glass is a constant threat, as these birds

are seldom ar rom human structures. Migrating

birds are oten orced to land in trees lining our side-walks, city parks, waterront business districts, and

other urban green patches that have replaced their

traditional stopover sites.

The amount o glass in a building is the strongest

predictor o how dangerous it is to birds. However,

even small areas o glass can be lethal. While bird kills

at homes are estimated at one to ten birds per home

The Common Yellowthroat may be the most common warblers in NorthAmerica and is also one o the most common victims o collisions with

glass. Photo: Owen Deutsch

in construction. This is maniest in an increase in

picture windows on private homes and new appli-

cations or glass are being developed all the time.

Unortunately, as the amount o glass increases, so

does the incidence o bird collisions.

In recent decades, growing concern or the en-vironment has stimulated the development o

green standards and rating systems. The best

known is the Green Building Councils (GBC) Leader-

ship in Energy and Environmental Design, or LEED.

GBC agrees that green buildings should not threaten

Wildlie, but until recently, did not include language

addressing the threat o glass to birds.

Their Resource Guide, starting with the 2009 edition,

calls attention to parts o existing LEED credits that

can be applied to reduce negative impacts on birds.

(One example: reducing light pollution saves energy

and benets birds.) As o October 14, 2011, GBC has

added Credit 55: Bird Collision Deterrence, to their

Pilot Credit Library (http://www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.

aspx?DocumentID=10402), drated by ABC, mem-

bers o the Bird-sae Glass Foundation, and the GBC

Site Subcommittee.

per year, the large number o homes multiplies that

loss to millions o birds per year in the United States.

Other actors can increase or decrease a buildings

impact, including the density and species composi-

tion o local bird populations, local geography, the

type, location, and extent o landscaping and nearby

habitat, prevailing wind and weather, and patterns omigration through the area. All must be considered

when planning bird-riendly buildings.

Impact o Collisions on Bird PopulationsAbout 25% o species are now on the U.S. WatchList

o birds o conservation concern (www.abcbirds.org/

abcprograms/science/watchlist/index.html), and

even many common species are in decline. Habitat

destruction or alteration on both breeding and win-

tering grounds remains the most serious man-madeproblem, but collisions with buildings are the largest

known atality threat. Nearly one third o the bird

species ound in the United States, over 258 species,

rom hummingbirds to alcons, are documented as

victims o collisions. Unlike natural hazards that pre-

dominantly kill weaker individuals, collisions kill all

categories o birds, including some o the strongest,

healthiest birds that would otherwise survive to

produce ospring. This is not sustainable and most

o the mortality is avoidable. This document is onepiece o a strategy to keep building collisions rom

increasing, and ultimately, to reduce them.

The Impact o Trends in ModernArchitectureIn recent decades, advances in glass technology

and production have made it possible to construct

buildings with all-glass curtain walls, and we have

seen a general increase in the amount o glass usedWarblers, such as this Black-and-white, are oten killed by window collisions

as they migrate. Photo: Luke Seitz

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

9/58

9Bird-Friendly Building Design

Essential to this credit is quantiying the threat level

to birds posed by dierent materials and design

details. These threat actors are used to calculate an

index representing the buildings aade and that

index must be below a standard value to earn the

credit. The credit also requires adopting interior

and exterior lighting plans and post-constructionmonitoring. The section on Research in Appendix

I reviews the work underlying the assignment o

threat actors.

ABC is a registered provider o AIA continuing

education, with classes on bird-riendly design

and LEED Pilot Credit 55 available in ace-to-ace

and webinar ormats. Contac t Christine Sheppard,

[email protected], or more inormation.

Dening Whats Good or BirdsIt is increasingly common to see the phrase bird-

riendly used in a variety o situations to demonstrate

that a particular product, building, legislation, etc., is

not harmul to birds. All too oten, however, this term is

unaccompanied by a clear denition, and lacks a sound

scientic oundation to underpin its use.

Ultimately, dening bird riendly is a subjective task.

Is bird-riendliness a continuum, and i so, where does

riendly become unriendly? Is bird-riendly the same

as bird-sae? How does the denition change rom use

to use, situation to situation?

It is impossible to know exactly how many birds

a particular building will kill beore it is built, and

so realistically, we cannot declare a building to be

bird-riendly beore it has been careully monitored

or several years. However, there are several actors

that can help us predict whether a building will be

The Hotel Puerta America in Mexico City was designed by Jean Nouvel, andeatures external shades. This is a fexible strategy or sun control, as well aspreventing collisions; shades can be lowered selectively when and whereneeded. Photo: Ramon Duran

particularly harmul to birds or generally benign,

and we can accordingly dene simple bird-smart

standards that, i ollowed, will ensure a prospective

building poses a minimal potential hazard to birds.

ABCs Bird-Friendly Building Standard

A bird-riendly building is one where:

Atleast90%ofexposedfaadematerialfrom

ground level to 40 eet (the primary bird

collision zone) has been demonstrated in

controlled experiments1 to deter 70% or

more o bird collisions

Atleast60%ofexposedfaadematerialabove

the collisions zone meets the above standard

Therearenotransparentpassagewaysorcor-

ners, or atria or courtyards that can trap birds

Outsidelightingisappropriatelyshieldedand

directed to minimize attraction to night-

migrating songbirds2

Interiorlightingisturnedoatnightorde-

signed to minimize light escaping through

windows

Landscapingisdesignedtokeepbirdsaway

rom the buildings aade3

Actualbirdmortalityismonitoredandcompen-

sated or (e.g., in the orm o habitat preserved

or created elsewhere, mortality rom other

sources reduced, etc.)

1See the section Research: Deterring Bird Collisions inAppendix I or inormation on these controlledstudies.

2See the section Solutions: Lighting Design on page 31

3See Landscaping and Vegetation, Appendix I on Page 40

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

10/58

Problem: Glass

The glass in this Washington, DC atrium poses a double hazard, drawingbirds to plants inside, as well as refecting sky above. Photo: ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

11/58

11Bird-Friendly Building Design

The Properties o GlassGlass can appear very dierently depending on a number o

actors, including how it is abricated, the angle at which it

is viewed, and the dierence between exterior and interior

light levels. Combinations o these actors can cause glass to

look like a mirror or dark passageway, or to be completely

invisible. Humans do not actually see most glass, but arecued by context such as mullions, roos or doors. Birds, how-

ever, do not perceive right angles and other architectural

signals as indicators o obstacles or articial environments.

ReectionViewed rom outside, transparent glass on buildings is oten

highly refective. Almost every type o architectural glass,

under the right conditions, refects the sky, clouds, or nearby

habitat amiliar and attractive to birds. When birds try to fy

to the refected habitat, they hit the glass. Refected vegeta-

tion is the most dangerous, but birds also attempt to fy pastrefected buildings or through refected passageways.

TransparencyBirds strike transparent windows as they attempt to access

potential perches, plants, ood or water sources, and other

lures seen through the glass. Glass skywalks joining build-

ings, glass walls around planted atria, windows installed per-

pendicularly on building corners, and exterior glass handrails

or walkway dividers are dangerous because birds perceive

an unobstructed route to the other side.

Black Hole or Passage EfectBirds oten fy through small gaps, such as spaces between

leaves or branches, nest cavities, or other small openings. In

some light, glass can appear black, creating the appearance o

just such a cavity or passage through which birds try to fy.

Factors Afecting Rates o Bird Collisionsor a Particular Building

Every site and every building can be characterized as aunique combination o risk actors or collisions. Some,

particularly aspects o a buildings design, are very building-

specic. Many negative design eatures can be readily coun-

tered, or, in new construction, avoided. Others, or example

a buildings location and siting, relate to migration routes,

regional ecology, and geographyactors that are dicult i

not impossible to modiy.

The glass-walled towers o the Time-Warner Center in New York City appear to birdsas just another piece o the sky. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Architectural cues show people that only one panel on the aceo this shelter is open; to birds, all the panels appear to be open.Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Transparent handrails are a dangerous trend or birds, especiallywhen they ront vegetation. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

12/58

12 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Building DesignGlass causes virtually all bird collisions with buildings. The

relative threat posed by a particular building depends sub-

stantially on the amount o exposed glass, as well as the

type o glass used, and the presence o glass design traps.

Klem (2009) in a study based on data rom Manhattan, New

York, ound that a 10% increase in the area o refective andtransparent glass on a building aade correlated with a 19%

increase in the number o atal collisions in spring and a 32%

increase in all.

Type o GlassThe type o glass used in a building is a signicant compo-

nent o its danger to birds. Mirrored glass is oten used to

make a building blend into an area by refecting its sur-

roundings. Unortunately, this makes those buildings espe-

cially deadly to birds. Mirrored glass is refective at all timeso day, and birds mistake refections o sky, trees, and other

habitat eatures or reality. Non-mirrored glass can be highly

refective at one time, and at others, appear transparent or

dark, depending on time o day, weather, angle o view, and

other variables, as with the window pictured below. Tinted

glass reduces collisions, but only slightly. Low-refection

glass may be less hazardous in some situations, but does not

actively deter birds and can create a passage eect, appear-

ing as a dark void that could be fown through (see page 11).

Building SizeAs building size increases or a particular design, so usually

does the amount o glass, making larger buildings more o a

threat. It is generally accepted that the lower stories o build-

ings are the most dangerous because they are at the same

level as trees and other landscape eatures that attract birds.

However, monitoring programs accessing setbacks and roos

o tall buildings are nding that birds also collide with higher

levels.

Building Orientation and SitingBuilding orientation in relation to compass direction has not

been implicated as a actor in collisions, but siting o a build-

ing with respect to surrounding habitat and landscaping can

be an issue, especially i glass is positioned so that it refects

vegetation. Physical eatures such as outcrops or pathways

that provide an open fight path through the landscape canchannel birds towards or away rom glass and should be

considered early in the design phase.

Design TrapsWindowed courtyards and open-topped atria can be death

traps or birds, especially i they are heavily planted. Birds

fy down into such places, and then try to leave by fying

directly towards refections on the walls. Glass skywalks and

outdoor handrails, and building corners where glass walls or

windows are perpendicular are dangerous because birds cansee through them to sky or habitat on the other side.

Birds fying rom a meadow on the l et are channeled towards the glass doors o thisbuilding by a rocky outcrop to the right o the path. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Large acing panes o glass can appear to be a clear pathway.Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

The same glass can appear transparent or highly refective,depending on weather or time o day. Photo: Christine

Sheppard, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

13/58

13Bird-friendly Building Design

Mirrored glass is dangerous at all times o day, whether it refects vegetation, sky, or simply open spacethrough which a bird might try to fy. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

14/58

14 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Reected VegetationGlass that refects shrubs and trees causes more collisions

than glass that refects pavement or grass (Gelb and Delec-

retaz,2006).Studieshaveonlyquantiedvegetationwithin

15-50 eet o a aade, but refections can be visible at much

greater distances. Vegetation around buildings will bring

more birds into the vicinity o the building; the refection o

that vegetation brings more birds into the glass. Taller trees

and shrubs correlate with more collisions. It should be kept

in mind that vegetation on slopes near a building will refectin windows above ground level. Studies with bird eeders

(Klem et al., 1991) have shown that atal collisions result

when birds fy towards glass rom more than a ew eet away.

Green Roos and WallsGreen roos bring habitat elements attractive to birds to

higher levels, oten near glass. However, recent work shows

that well designed green roos can become unctional

ecosystems, providing ood and nest sites or birds. Siting

o green roos, as well as green walls and rootop gardens

should thereore be careully considered, and glass adjacent

to these eatures should have protection or birds.

Local ConditionsAreas where og is common may exacerbate local light pol-

lution (see below). Areas located along migratory pathwaysor where birds gather prior to migrating across large bodies

o water, or example, in Toronto, Chicago, or the southern

tip o Florida, expose birds to highly urban environments

and have caused large mortality events (see Appendix II or

additional inormation on how migration can infuence bird

collisions).

LightingInterior and exterior building and landscape lighting can

make a signicant dierence to collisions rates in any one lo-cation. This phenomenon is dealt with in detail in the section

on lighting.

Refections on home windows are a signicant source o bird mortality. The partiallyopened vertical blinds seen here may break up the refection enough to reduce thehazard to birds. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Plantings on setbacks and rootops can attract birds to glassthey might otherwise avoid. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Vines cover most o these windows, but birds might fy intothe dark spaces on the right. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Planted, open atrium spaces lure birds down, then prove dangerous when birds try tofy out to refections on surrounding windows. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

15/58

15Bird-friendly Building Design

This atrium has more plants than anywhere outside on the surrounding streets, making the glass deadly or birds seeking ood in this area.Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

16/58

Solutions: Glass

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

17/58

17Bird-Friendly Building Design

It is possible to design buildings that can reasonably be

expected not to kill birds. Numerous examples exist, not

necessarily designed with birds in mind, but to be unctional

and attractive. These buildings may have windows, but use

screens, latticework, grilles, and other devices outside the

glass or integrated into the glass.

Finding glass treatments that can eliminate or greatly reduce

bird mortality while minimally obscuring the glass itsel

has been the goal o several researchers, including Martin

Rssler, Dan Klem, and Christine Sheppard. Their research,

discussed in more detail in Appendix I, has ocused primar-

ily on the spacing, width, and orientation o lines marked on

glass, and has shown that patterns covering as little as 5% o

the total glass surace can deter 90% o strikes under experi-

mental conditions. They have consistently shown that most

birds will not attempt to fy through horizontal spaces lessthan 2 high nor through vertical spaces 4 wide or less. We

reer to this as the 2 x 4 rule. There are many ways that this

can be used to make buildings sae or birds.

Designing a new structure to be bird riendly does not need

to restrict the imagination or add to the cost o construc-

tion. Architects around the globe have created ascinating

and important structures that incorporate little or no ex-

posed glass. In some cases, inspiration has been born out o

unctional needs, such as shading in hot climates, in others,

aesthetics; being bird-riendly was usually incidental. Ret-

rotting existing buildings can oten be done by targeting

problem areas, rather than entire buildings.

Emilio Embasz used creative lighting strategies to illuminate his Casa de Respira Espiritual, located north o Seville, Spain. Much o thestructure and glass are below grade, but are lled with refected light. Photo courtesy o Emilio Ambasz and Associates

(Opposite) The external glass screen on the GSA Regional Field Oce in Houston, TX,designed by Page Southerland Page, means windows are not v isible rom many angles.Photo: Timothy Hursley

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

18/58

18 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Facades, netting, screens, grilles, shutters,exterior shadesThere are many ways to combine the benets o glass with

bird-sae or bird-riendly design by incorporating elements

that preclude collisions without completely obscuring vi-

sion. Some architects have designed decorative acades that

wrap entire structures. Recessed windows can unctionallyreduce the amount o visible glass and thus the threat to

birds. Netting, screens, grilles, shutters and exterior shades

are more commonly used elements that can make glass

sae or birds. They can be used in retrots or be an integral

part o an original design, and can signicantly reduce bird

mortality.

Beore the current age o windows that are unable to be

opened, screens protected birds in addition to their primary

purpose o keeping bugs out. Screens and nets are still

among the most cost-eective methods or protecting birds,

and netting can oten be installed so as to be nearly invisible.

Netting must be installed several inches in ront o the win-

dow, so impact does not carry birds into the glass. Severalcompanies sell screens that can be attached with suction

cups or eye hooks or small areas o glass. Others specialize

in much larger installations.

Decorative grilles are also part o many architectural tradi-

tions, as are shutters and exterior shades, which have the

additional advantage that they can be closed temporarily,

specically during times most dangerous to birds, such as

migration and fedging (see Appendix II).

Functional elements such as balconies and balustrades can

act like a aade, protecting birds while providing an amenity

or residents.

FOA made extensive use o bamboo in the design o thisMadrid, Spain public housing block. Shutters are an excellentstrategy or managing bird collisions as they can be closed asneeded. Photo courtesy o FOA

The aade o the New York Times building, by FX Fowle and Renzo Piano, is composed o ceramic rods, spaced to let occupants see out, while minimizing

the extent o exposed glass. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

External shades on Renzo Pianos Caliornia Academy o Sciences in San Francisco arelowered during migration seasons to eliminate collisions. Photo: Mo Flannery

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

19/58

19Bird-Friendly Building Design

The combination o shades and balustrades screens glass on Os ArchitectsApartments on the Coast in Izola, Slovenia. Photo courtesty o Os

Instead o glass, this side o Jean Nouvels Institute Arabe du Monde in Paris,France eatures motor-controlled apertures that produce ltered light in theinterior o the building. Photo: Vicki Paull

For the Langley Academy in Berkshire, UK, Foster + Par tnersused louvers to control light and ventilation, also making thebuilding sae or birds. Photo: Chris Phippen Os

A series o balconies, such as those pictured here, can hide glass rom view.Photo: Elena Cazzaniga

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

20/58

20 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Awnings and OverhangsOverhangs have been said to reduce collisions, however,

they do not eliminate refections, and only block glass rom

the view o birds fying above. They are thus o limited eec-

tiveness as a general strategy.

UV Patterned GlassBirds can see into the ultraviolet (UV) spectrum o light, a

rangelargelyinvisibletohumans(seepage36).UV-reec-

tive and/or absorbing patterns (transparent to humans but

visible to birds) are requently suggested as the optimal

solution or many bird collision problems. Progress in the

search or bird-riendly UV glass has been slow, however,

due to the inherent technical complexities, and because,

in the absence o widespread legislation mandating bird-

riendly glass, only a ew glass companies recognize this as

a market opportunity. Research indicates that UV patternsneed strong contrast to be eective.

Angled GlassIn a study (Klem et al., 2004) comparing bird collisions with

vertical panes o glass to those tilted 20 degrees or 40 de-

grees, the angled glass resulted in less mortality. For this

reason, it has been suggested that angled glass should be

incorporated into buildings as a bird-riendly eature. While

angled glass may be useul in special circumstances, the

birds in the study were fying parallel to the ground romnearby eeders. In most situations, however, birds approach

glass rom many angles, and can see glass rom many per-

spectives. Angled glass is not recommended as appropriate

or useul strategy. The New York Times printing plant, pic-

tured opposite, clearly illustrates this point. The angled glass

curtain wall shows clear refections o nearby vegetation,

visible rom a long distance away.

Overhangs block viewing o glass rom some angles, but do notnecessarily eliminate refections. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Deeply recessed windows, such as these on Stephen Holls Simmons Hall at MIT, canblock viewing o glass rom most angles. Photo: Dan Hill

Refections in this angled aade can be seen clearly over a longdistance, and birds can approach the glass rom any angle. Photo:Christine Sheppard, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

21/58

Translucent glass panels on the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria, designed by Atelier Peter Zumthor, providelight and air to the building interior, without dangerous refections. Photo: William Heltz

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

22/58

22 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Patterns on GlassPatterns are oten applied to glass to reduce the trans-

mission o light and heat; they can also provide some

design detail. When designed according to the 2x4

rule, (see p. 17) patterns on glass can also prevent bird

strikes. External patterns on glass deter collisions e-

ectively because they block glass refections, acting likea screen. Ceramic dots or rits and other materials can

be screened, printed, or otherwise applied to the glass

surace. This design element, useul primarily or new

construction, is currently more common in Europe and

Asia, but is being oered by an increasing number o

manuacturers in the United States.

More commonly, patterns are applied to an internal

surace o double-paned windows. Such designs may

not be visible i the amount o light refected rom therit is insucient to overcome refections on the glass

outside surace. Some internal rits may only help break

up refections when viewed rom some angles and in

certain light conditions. This is particularly true or large

windows, but also depends on the density o the rit pat-

tern. The internet company IACs headquarters building

in New York City, designed by Frank Gehry, is composed

entirely o ritted glass, most o high density. No collision

mortalities have been reported at this building ater two

years o monitoring by Project Sae Flight. Current re-search is testing the relative eectiveness o dierent rit

densities, congurations, and colors.

The glass acade o SUVA Haus in Basel, Switzerland, reno-vated by Herzog and de Meuron, is screen-printed on theoutside with the name o the company owning the building.Photo: Miguel Marqus Ferrer

Dense stripes o internal rit on University HospitalsTwinsburg Health Center in Cleveland, by Westlake, Reed,Leskosky will overcome virtually all refections. Photo:Christine Sheppard, ABC

The Studio Gangs Aqua Tower in Chicago was designed with birds in mind.

Strategies include ritted glass and balcony balustrades. Photo: Tim Bloomquist

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

23/58

23Bird-Friendly Building Design

The dramatic City Hall o Alphen aan den Rijn in the Netherlands, designedby Erick van Egeraat Associated Architects, eatures a aade o etched glass.Photo: Dik Naagtegal

A detail o a pattern printed on glass at the Cottbus Media Centre inGermany. Photo: Evan Chakro

RAUs World Wildlie Fund Headquarters in the Netherlands useswooden louvers as sunshades; they also diminish the area o glassvisible to birds. Photo courtesy o RAU

External rit, as seen here on the Lile Museum o Fine Arts, by Ibosand Vitart, is more eective at breaking up refections than patternson the inside o the glass. Photo: G. Fessy

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

24/58

24 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Opaque and Translucent GlassOpaque, etched, stained, rosted glass, and glass block

can are excellent options to reduce or eliminate collisions,

and many attractive architectural applications exist. They

can be used in retrots but are more commonly in new

construction.

Frosted glass is created by acid etching or sandblasting

transparent glass. Frosted areas are translucent, but dierent

nishes are available with dierent levels o light transmis-

sion. An entire surace can be rosted, or rosted patterns

can be applied. Patterns should conorm to the 2x4 rule de-

scribed on page 17. For retrots, glass can also be rosted by

sandblasting on site.

Stained glass is typically seen in relatively small areas but can

be extremely attractive and is not conducive to collisions.

Glass block is extremely versatile, can be used as a design

detail or primary construction material, and is also unlikely

to cause collisions.

While some internal ritted glass patterns can be over-

come by refections, Frank Gehrys IAC Headquarters inManhattan is so dense that the glass appears opaque.Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Renzo Pianos Hermes Building in Tokyo has a aade o glass block.Photo: Mariano Colantoni

Frosted glass aade on the Wexord Science and Technology building in Philadelphia,by Zimmer, Gunsul, Frasca. Photo: Walker Glass

UN Studios Het Valkho Museum in Nijmegan, TheNetherlands, uses translucent glass to diuse light tothe interior, which also reduces dangerous refections.Photo courtesy o UN Studio.

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

25/58

25Bird-Friendly Building Design

A dramatic use o glass block denotes the Hecht Warehouse in Washington, DC,by Abbott and Merkt. Photo: Sandra Cohen-Rose and Colin Rose

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

26/58

26 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Internal Shades, Blinds, and CurtainsLight colored shades are oten recommended as a way to de-

ter collisions. However, they do not eectively reduce refec-

tions and are not visible rom acute angles. Blinds have the

same problems, but when visible and partly open, they are

more likely to break up refections than solid shades.

Window FilmsCurrently, most patterned window lms are intended or use

inside structures as design elements or or privacy, but this is

beginning to change. 3MTM ScotchcalTM Perorated Window

Graphic Film, also known as CollidEscape, is a well-known

external solution. It covers the entire surace o a window,

appears opaque rom the outside, but still permits a view out

rom inside. Interior lms, when applied correctly, have held

up well in external applications, but this solution has not yet

been tested over decades. A lm with a pattern o narrow,horizontal stripes was applied to a building, in Markham, On-

tario and successully eliminated collisions. Another lm has

been eective at the Philadelphia Zoos Bear Country exhibit

(see photo on opposite page). In both cases, the response o

people has also been positive.

Temporary SolutionsIn some circumstances, especially or homes and small build-

ings, quick, low-cost, temporary solutions such as making

patterns on glass with tape or paint can be very eective.

Even a modest eort can reduce collisions. Such measures

can be applied when needed and are most eective ollow-

ing the 2x4 rule. For more inormation, see ABCs inorma-tive fyer You Can Save Birds rom Flying into Windows at

www.abcbirds.org/abc

DecalsDecals are probably the most popularized solution to bird

collisions, but their eectiveness is widely misunderstood.

Birds do not recognize decals as silhouettes o birds, spider

webs, or other items, but simply as obstacles that they may

try to fy around. Decals are most eective i applied ollow-ing the 2 x 4 rule, but even a ew may reduce collisions.

Because decals must also be replaced requently, they are

usually considered a short-term strategy or small windows.

A single decal is ineective or collision prevention on a window o this size, as birdswill simply attempt to fy around it. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Tape decals (Window Alert shown here) placed ollowing the 2 x 4 rule can be eectiveat deterring collisions. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

ABC BirdTape

Photos : Dariusz Zdziebkowski, ABC

ABC, with support rom the

Rusinow Family Foundation, has

produced ABC BirdTape to make

home windows saer or birds.This easy-to-apply tape lets birds

see glass while letting you see

out, is easily applied, and lasts

up to our years.

For more inormation, visit

www.ABCBirdTape.org

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

27/58

This window at the Philadelphia Zoos Bear Country exhibit was the site o requent birdcollisions until this window lm was applied. Collisions have been eliminated, with nocomplaints rom the public. Photo courtesy o Philadelphia Zoo

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

28/58

Problem: Lighting

Each white speck seen here is a bird, trapped in the beams olight orming the 9/11 Tribute in Lightin New York City. Volunteerswatch during the night and the lights are turned o briefy i largenumbers o birds are observed. Photo: Jason Napolitano

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

29/58

29Bird-Friendly Building Design

Articial light is increasingly recognized as a negative actor

forhumansaswellaswildlife.RichandLongcore(2006)have

gathered comprehensive reviews o the impact o ecological

light pollution on vertebrates, insects, and even plants. For

birds especially, light can be a signicant and deadly hazard.

Beacon Efect and Urban GlowLight at night, especially during bad weather, creates con-

ditions that are particularly hazardous or night-migrating

birds. Typically fying at altitudes over 500 eet, migrants

oten descend to lower altitudes during inclement weather,

where they may encounter articial light rom buildings.

Water vapor in very humid air, og, or mist reracts light,

orming an illuminated halo around light sources.

There is clear evidence that birds are attracted to light, and

once close to the source, are unable to break away (Rich and

Longcore,2006;Pootetal.,2008;GauthreauxandBelser,

2006).Howdoesthisbecomeahazardtobirds?Whenbirds

encounter beams o light, especially in inclement weather,

they tend to circle in the illuminated zone, appearing dis-

oriented and unwilling or unable to leave. This has been

documented recently at the 9/11 Memorial in Lights, where

lights must be turned o briefy when large numbers o birds

become caught in the beams. Signicant mortality o migrat-

ing birds has been reported at oil platorms in the North Sea

and the Gul o Mexico. Van de Laar (2007) tested the impacton birds o lighting on an o-shore platorm. When lights

were switched on, birds were immediately attracted to the

platorm in signicant numbers. Birds dispersed when lights

were switched o. Once trapped, birds may collide with

structures or each other, or all to the ground rom exhaus-

tion, where they are at risk rom predators.

While mass mortalities at very tall illuminated structures

(such as skyscrapers) during inclement weather have

received the most attention, mortality has also been

associated with ground-level lighting during clear weather.

Light color also plays a role, with blue and green light much

saer than white or red light. Once birds land in lighted areas,

they are at risk rom colliding with nearby structures as they

orage or ood by day.

In addition to killing birds, overly-lit buildings waste electric-

ity, and increase greenhouse gas emissions and air pollu-

tion levels. Poorly designed or improperly installed outdoor

xtures add over one billion dollars to electrical costs in the

United States every year, according to the I nternational Dark

Skies Association. Recent studies estimate that over two

thirds o the worlds population can no longer see the Milky

Way, just one o the nighttime wonders that connect people

with nature. Together, the ecological, nancial, and cultural

impacts o excessive building lighting are compelling rea-

sons to reduce and rene light usage.

Houston skyline at night. Photo: Je Woodman

Overly-lit buildings waste electricity and increase greenhousegas emissions and air pollution levels, as well as posing a threatto birds. Photo: Matthew Haines

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

30/58

Solutions: Lighting Design

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

31/58

31Bird-Friendly Building Design

Reducing exterior building and site lighting has proven e-

ective at reducing mortality o night migrants. At the same

time, these measures reduce building energy costs and de -

crease air and light pollution. Ecient design o lighting sys-

tems plus operational strategies to reduce light trespass or

spill light rom buildings while maximizing useul light are

both important strategies. In addition, an increasing body oevidence shows that red lights and white light (which con-

tains red wavelengths) particularly attract and conuse birds,

while green and blue light have ar less impact.

Light pollution is largely a result o inecient exterior light-

ing, and improving lighting design usually produces savings

greater than the cost o changes. For example, globe xtures

permit little control o light, which shines in all directions, re-

sulting in a loss o as much as 50% o energy, as well as poor

illumination. Cut-o shields can reduce lighting loss and per-

mit use o lower powered bulbs.

Most vanity lighting is unnecessary. However, when it is

used, building eatures should be highlighted using down-

lighting rather than up-lighting. Where light is needed or

saety and security, reducing the amount o light trespass

outside o the needed areas can help by eliminating shad-

ows. Spotlights and searchlights should not be used during

bird migration. Communities that have implemented pro-

grams to reduce light pollution have not ound an increase

in crime.

Using automatic controls, including timers, photo-sensors,

and inrared and motion detectors is ar more eective than

reliance on employees turning o lights. These devices gen-

erally pay or themselves in energy savings in less than a

year. Workspace lighting should be installed where needed,

rather than lighting large areas. In areas where indoor lights

will be on at night, minimize perimeter lighting and/or draw

shades ater dark. Switching to

daytime cleaning is a simple

way to reduce lighting while

also reducing costs.

Lights Out ProgramsBirds evolved complex, comple-

mentary systems or orientation

and vision long beore humans

developed articial light. We

still have much more to learn,

especially the dierences be-

tween species, but recent sci-

ence has begun to clariy how

articial light poses a threat to birds, especially nocturnal mi-

grants. These birds use a magnetic sense which is dependent

on dim light rom the blue-green end o the spectrum.

Research has shown that dierent wavelengths cause di-

erent behaviors, with yellow and red light preventing ori-

entation. Dierent intensities o light also produce dierent

(Opposite) Fixtures such as these reduce light pollution, saving energy and money, andreducing negative impacts on birds. Photo: Dari usz Zdziebkowski, ABC

Shielded light xtures are widely available inmany dierent styles. Photo: Susan Harder

Reprinted courtesy o DarkSkySociety.org

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

32/58

32 Bird-Friendly Building Design

reactions. Despite the complexity o this issue, there is one

simple way to reduce mortality: turn lights o.

Across the United States and Canada, Lights Out programs

at the municipal and state level encourage building owners

and occupants to turn out lights visible rom outside during

spring and all migration. The rst o these, Lights Out Chi-

cago, was started in 1995, ollowed by Toronto in 1997. There

are over twenty programs as o mid-2011.

The programs themselves are diverse. Some are directed by

environmental groups, others by government departments,

and still others by partnerships o organizations. Participa-

tion in some, such as Houstons, is voluntary. Minnesota

mandates turning o lights in state-owned and -leased

buildings, while Michigans governor proclaims Lights Out

dates annually. Many jurisdictions have a monitoring compo-

nent or work with local rehabilitators. Monitoring programs

can provide important inormation in addition to quantiy-

ing collision levels and documenting solutions. Toronto, or

example, determined that i short buildings emit more light,

they can be more dangerous to birds than tall building emit-ting less light.

Ideally, Lights Out programs would be in eect year round,

saving birds and energy costs and reducing emissions o

greenhouse gases. ABC stands ready to help develop new

programs and to support and expand existing programs.

Red: state ordinance

Yellow: cities in state-wideprograms

Turquoise: programin development

Blue: local programs

Lights Outmap legend

Distribution o Lights Out Programs in North America

Shielded lights, such as those shown above, cut down on lightpollution and are much saer or birds. Photo: Susan Harder

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

33/58

33Bird-Friendly Building Design

Downtown Houston during Lights Out. Photo: Je Woodman

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

34/58

34 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Solutions: Legislation

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

35/58

35Bird-Friendly Building Design

Changing human behavior is generally a slow pro-

cess, even when the change is uncontroversial.

Legislation can be a powerul tool or modiying be-

havior. Conservation legislation has created reserves,

reduced pollution, and protected threatened spe-

cies and ecosystems. Initial eorts to document bird

mortality and recommend ways to remediate col-lisions have more recently given way to legislation

that promotes bird-riendly design and reduction o

light pollution.

Most o these ordinances reer to external guide -

lines, rather than speciying how their goals must be

achieved, and because there are many guidelines,

created at dierent times and oten specic to par-

ticular places, this can lead to contradiction, conu-

sion, and cases o shopping or the cheapest option.

These ABC guidelines are intended to address colli-sions at a national level and may be distributed by

other groups.

One challenge in creating legislation is to provide

specic strategies and create objective measures

that architects can use to accomplish their task. ABC

has incorporated objective criteria into this docu-

ment and created a model ordinance to be ound in

Appendix V .

ABC is willing to partner with local groups in creat-ing additions to the Guidelines with local ocus and

to assist in promoting local, bird-riendly legislation.

Cook County, Illinois, was the rst to pass bird-

riendly construction legislation, sponsored by

then-Assemblyman Mike Quigley.

In2006,Toronto,Canada,proposedaGreenDe-

velopment Standard, initially a set o voluntary

guidelines to promote sustainable site and build-

ing design, including guidelines or bird-riendly

construction. Development Guidelines became

mandatory on January 1, 2011, but the process o

translating guidelines into blueprints is still under-way. San Francisco adopted Standards or Bird-sae

Buildings in September, 2011. Listed below are some

examples o current and pending ordinances at lev-

els rom ederal to municipal.

Federal (proposed)

Illinois Congressman Mike Quigley (D-IL) introduced theFederalBird-SafeBuildingsActof2011(HR1643),which

calls or each public building constructed, acquired, oraltered by the General Services Administration (GSA) to in-corporate, to the maximum extent possible, bird-sae build-

ing materials and design eatures. The legislation wouldrequire GSA to take similar actions on existing buildings,where practicable. Importantly, the bill has been deemedcost-neutral by the Congressional Budget Oce. See http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c112:H.R.1643.IH

State: Minnesota (enacted)

Chapter 101, Article 2, Section 54: Between March 15 andMay 31, and between August 15 and October 31 eachyear, occupants o state-owned or state-leased build-ings must attempt to reduce dangers posed to migratingbirds by turning o building lights between midnight and

dawn, to the extent turning o lights is compatible withthe normal use o the buildings. The commissioner o ad-ministration may adopt policies to implement this require-ment. See www.revisor.leg.state.mn.us/laws/?id=101&doctype=Chapter&year=2009&type=0

State: Minnesota (enacted; regulationspending)

Beginning on July 1, 2010, all Minnesota State bondedprojects new and substantially renovated that have notalready started the schematic design phase on August 1,2009 will be required to meet the Minnesota SustainableBuilding 2030 (SB 2030) energy standards. Seewww.mn2030.umn.edu/

State: New York (pending)

BillS04204/A6342-A,theBird-friendlyBuildingsAct,re-quires the use o bird-riendly building materials and de-sign eatures in buildings. See http://assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?bn=S04204&term=2011

City: San Francisco (enacted)

The citys Planning Department has developed the rst seto objective standards in the nation, dening areas wherethe regulations are mandated and others where they arerecommended, plus including criteria or ensuring that

designs will be eective or protecting birds. See http://www.sf-planning.org/index.aspx?page=2506

City: Toronto

On October 27, 2009, the Toronto City Council passed amotion making parts o the Toronto Green Standard man-datory. The standard, which had previously been voluntary,applies to all new construction in the city, and incorporatesspecic Bird-Friendly Development Guidelines, designed toeliminate bird collisions with buildings both at night and inthe daytime.

Beginning January 31, 2010, all new, proposed low-rise,

non-residential, and mid- to high-rise residential and in-dustrial, commercial, and institutional development willbe required under Tier 1 o the Standard, which appliesto all residential apar tment buildings and non-residentialbuildings that are our stories tall or higher. See www.toronto.ca/planning/environment/greendevelopment.htm

United States Capitol, Washington, DC . Photo: stock.xchng

Song Sparrow: Greg Lavaty

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

36/58

36 Bird-Friendly Building Design

The number of birds killed by collisions with glass every year is astronomical.

Hundreds o species o birds are kil led by collisions. These birds were collected by monitors with FLAP in Toronto, Canada. Photo: Kenneth Herdy

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

37/58

37Bird-Friendly Building Design

Magnitude o Collision DeathsThe number o birds killed by collisions with glass ev-

ery year is astronomical. Based on studies o homesand commercial structures, Klem (1990) estimated

conservatively that each building in the United States

killsonetotenbirdsperyear.Using1986United

States Census data, he combined numbers o homes,

schools, and commercial buildings or a maximum

totalof97,563,626buildings.Dunn(1993)surveyed

5,500 people who ed birds at their homes and re-

corded window collisions. She derived an estimate

of0.65-7.7birddeathsperhomeperyearforNorth

America, supporting Klems calculation.

The number o buildings in the United States has

increasedsignicantlysince1986,andithasbeen

shown that commercial buildings generally kill more

than ten birds per year, as would be expected since

they have large expanses o glass (Hager et al., 2008;

OConnell, 2001). Thus, one billion annual atalities

is likely to be closer to reality, and possibly even too

low.

Klem et al., (2009a) used data rom New York CityAudubons monitoring o seventy-three Manhattan

building acades to estimate 0.5 collision deaths per

acre per year in urban environments, or a total o

about 34 million migratory birds annually colliding

with city buildings in the United States.

Patterns o MortalityIt is dicult to get a complete and accurate picture

o avian mortality rom collisions with glass. Collisiondeaths can occur at any time. Even intensive monitor-

ing programs only cover a portion o a city, usually

visiting the ground level o a given site at most once

a day and oten only during migration seasons. Many

city buildings have stepped roo setbacks that are

inaccessible to monitoring teams. Recognizing these

limitations, some papers have ocused on reports

rom homeowners on backyard birds (Klem, 1989;

Dunn, 1993) or on mortality o migrants in an urban

environment (Gelb and Delacretaz, 2009; Klem et al.,2009a, Newton, 1999). Others have analyzed collision

victims rom single, large-magnitude incidents (Sealy,

1985) or that have become part o museum collec-

tions(Snyder,1946;Blemetal.,1998;Codoner,1995).

There is general support or the act that birds killed

in collisions are not distinguished by age, sex, size,

or health (or example: Blem and Willis, 1998; Codo-

ner, 1995; Fink and French, 1971; Hager et al., 2008;

Klem, 1989). However, some species, such as the

White-throated Sparrow, Ovenbird, and Common

Yellowthroat, seem to be more vulnerable than oth-

ers, appearing consistently on top ten lists. Snyder(1946),examiningwindowcollisionfatalitiesatthe

Royal Ontario Museum, noted that the majority were

tunnel fyers species that requently fy through

small spaces in dense, understory habitat. Recent

work (J. A. Clark, pers. comm.) suggests that there

may be species dierences in attraction to light that

could explain these ndings. Interestingly, species

well adapted to and common in urban areas, such as

the House Sparrow and European Starling, are not

prominent on lists o atalities, and there is evidencethat resident birds are less likely to die rom collisions

than migratory birds.

Collision mortality appears to be a density-indepen-

dent phenomenon. Hager et al. (2008) compared

the number o species and individual birds killed at

buildings at Augustana College in Illinois with the

density and diversity o bird species in the surround-

ing area. The authors concluded that total window

area, habitat immediately adjacent to windows, and

APPENDIX I: THE SCIENCE OF BIRD COLLISIONS

A sample o collision victi ms rom Baltimore.Photo: Daniel J. Lebbin, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

38/58

38 Bird-Friendly Building Design

behavioral dierences among species were the

best predictors o mortality patterns, rather than

simply the size and composition o the local bird

population.

From a study o multiple Manhattan buildings in

New York City, Klem et al(2009a) similarly concluded

that the expanse o glass on a building acade is the

actor most predictive o mortality rates, calculating

that every increase o 10% in the expanse o glass

correlates to a 19% increase in bird mortality in

spring, 32% in all. How well these equations predict

mortality in other cities remains to be tested. Collins

and Horn (2008) studying collisions at Millikin Uni-

versity in Illinois concluded that total glass area and

the presence/absence o large expanses o glass pre-

dicted mortality level. Hager et al(2008) came to the

same conclusion. Gelb and Delacretazs (2009) work

in New York City indicated that collisions are more

likely to occur on windows that refect vegetation.

Dr. Daniel Klem maintains running totals o the num-

ber o species reported in collision events in countries

around the world. This inormation can be ound at:

www.muhlenberg.edu/main/academics/biology/ac-

ulty/klem/aco/Country%20list.htm#World

He notes 859 species globally, with 258 rom theUnited States. The intensity o monitoring and re-

porting programs varies widely rom country to

country, however. Hager (2009) noted that window

strike mortality was reported or 45% o raptor spe-

cies ound requently in urban areas o the United

States, and represented the leading source o mor-

tality or Sharp-shinned Hawks, Coopers Hawks,

Merlins, and Peregrine Falcons.

Avian Vision and CollisionsTaking a birds-eye view is much more complicated

than it sounds. To start with, where human color vi-

sion relies on three types o sensors, birds have our,

plus an array o color lters that allow them to see

many more colors than people (Varela et al., 1993)

(see chart below). Many birds, including most pas-serines (deen and Hstad, 2003) also see into the

ultraviolet spectrum. Ultraviolet can be a compo-

nent o any color (Cuthill et al., 2000). Where humans

see red, yellow, or red + yellow, birds may see red +

yellow, but also red + ultraviolet, yellow + ultraviolet,

and red + yellow + ultraviolet, colors or which we

have no names. They can also see polarized light

(Muheim et al.,2006,2011),andtheyprocessim-

ages aster than humans; where we see continuous

motion in a movie, birds would see fickering images

(DEath, 1998; Greenwood et al., 2004; Evans et al.,

2006).Totopitallo,birdshavenotone,buttwo

receptors that permit them to sense the earths mag-

netic eld, which they use or navigation (Wiltschko et

al.,2006).

Avian Orientation andthe Earths Magnetic FieldThirty years ago, it was discovered that birds possess

the ability to orient themselves relative to the Earths

magnetic eld and locate themselves relative to

their destination. They appear to use cues rom the

sun, polarized light, stars, the Earths magnetic eld,

visual landmarks, and even odors to nd their way.

Exactly how this works and it likely varies among

nm 350 400 450 500 550 600 650

560

565

530424

445370 508

Comparison o Human and Avian Vision

Based on artwork by Sheri Williamson

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

39/58

39Bird-Friendly Building Design

species is still being investigated, but there have

been interesting discoveries that also shed light on

light-related hazards to migrating birds.

Lines o magnetism between the north and south

poles have gradients in three dimensions. Cells in

birds upper beaks, or maxillae, contain the iron

compounds maghemite and magnetite. Micro-

synchrotron x-ray fuorescence analysis shows these

compounds in three dierent compartments, a

three-dimensional architecture that probably allows

birds to detect their map (Davila, 2003; Fleissner et

al., 2003, 2007). Other magnetism-detecting struc-

tures are ound in the retina o the eye, and depend

on light or activity. Light excites receptor molecules,

setting o a chain reaction. The chain in cells that re-

spond to blue wavelengths includes molecules that

react to magnetism, producing magnetic directional

cues as well as color signals. For a comprehensive

review o the mechanisms involved in avian orienta-

tion, see Wiltschko and Wiltschko, 2009.

Birds and Light Pollution

The earliest reports o mass avian mortality causedby lights were rom lighthouses, but this source o

mortality essentially disappeared when steady-burn-

ing lights were replaced by rotating beams (Jones

and Francis, 2003). Flashing or interrupted beams

apparently allow birds to continue to navigate. While

mass collision events at tall buildings and towers

havereceivedmostattention(Weir,1976;Averyet

al., 1977; Avery et al., 1978; Craword, 1981a, 1981b;

Newton, 2007), light rom many sources, rom urban

sprawl to parking lots, can aect bird behavior and

cause bird mortality (Gocheld, 1973). Gocheld (in

RichandLongcore,2006)notedthatbirdhunters

throughout the world have used lights rom res or

lanterns near the ground to disorient and net birds

on cloudy, dark nights. In a review o the eects o

articial light on migrating birds, Gauthreaux and

Belser(2006)reportontheuseofcarheadlightstoattract birds at night or tourists on saari.

Evans-Ogden (2002) showed that light emission lev-

els o sixteen buildings ranging in height rom eight

to 72 foors correlated directly with bird mortality,

and that the amount o light emitted by a structure

was a better predictor o mortality level than build-

ing height, although height was a actor. Wiltschko

et al(2007) showed that above intensity thresholds

that decrease rom green to UV, birds showed dis-

orientation. Disorientation occurs at light levels that

are still relatively low, equivalent to less than hal an

hour beore sunrise under clear sky. It is thus likely

that light pollution causes continual, widespread,

low-level mortality that collectively is a signicant

problem.

The mechanisms involved in both attraction to and

disorientation by light are poorly understood and

may dier or dierent light sources (see Gauthreaux

andBelser(2006)andHerbert(1970)forreviews.)

Recently, Haupt and Schillemeit described the paths

o 213 birds fying through beams uplighting rom

several dierent outdoor lighting schemes. Only

7.5% showed no change in behavior. Migrating birds

are severely impacted, while resident species may

show little or no eect. It is not known whether this

is because o dierences in physiology or simply a-

miliarity with local habitat.

Steady-burning red and white lights are most dangerous to birds. Photo: Mike Parr, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

40/58

40 Bird-Friendly Building Design

Light Color and Avian OrientationStarting in the 1940s, ceilometers, powerul beams

o light used to measure the height o cloud cover,

came into use, and were associated with signicant

bird kills. Filtering out long (red) wavelengths and

using the blue/ultraviolet range greatly reduced

mortality. Later, replacement o xed beam ceilom-eters with rotating beams essentially eliminated

impactonmigratingbirds(Laskey,1960).Acomplex

series o laboratory studies in the 1990s demon-

strated that birds required light in order to sense the

Earths magnetic eld. Birds could orient correctly

under monochromatic blue or green light, but lon-

ger wavelengths (yellow and red) caused disorienta-

tion (Rappli et al., 2000; Wiltschko et al., 1993, 2003,

2007). It was demonstrated that the magnetic recep-

tor cells on the eyes retina are inside the type ocone cell responsible or processing blue and green

light, but disorientation seems to involve a lack o

directional inormation.

Poot et al. (2008) demonstrated that migrating birds

exposed to dierent colored lights in the eld re-

spond the same way they do in the laboratory. Birds

were strongly attracted to white and red light, and

appeared disoriented by them, especially under

overcast skies. Green light was less attractive and

minimally disorienting; blue light attracted ew birdsand did not disorient those that it did attract (but

see Evans et al., 2007). Birds were not attracted to in-

rared light. This work was the basis or development

o the Phillips Clear Sky bulb, which produces white

light with minimal red wavelengths (Marquenie et

al., 2008) and is now in use in Europe on oil rigs and

at some electrical plants. According to Van de Laar

et al. (2007), tests with this bulb on an oil platorm

during the 2007 all migration produced a 50-90%

reduction in birds circling and landing. Recently,Gehring et al. (2009) demonstrated that mortality at

communication towers was greatly reduced i strobe

lighting was used as opposed to steady-burning

white, or especially red lights. Replacement o steady-

burning warning lights with intermittent lights at

locations causing collisions is an excellent option or

protecting birds, as is manipulating light color.

Weather Impact on Collisions

Weather has a signicant and complex relationshipwith avian migration (Richardson, 1978), and large-

scale, mass mortality o migratory birds at tall, light-

ed structures (including communication towers) has

oten correlated with og or rain (Avery et al., 1977;

Craword, 1981b; Newton, 2007) The conjunction o

bad weather and lighted structures during migra-

tion is a serious threat, presumably because visual

cues used by birds or orientation are not available.

However, not all collision events take place in bad

weather. For example, in a report o mortality at a

communications tower in North Dakota (Avery et al.,

1977), the weather was overcast, usually with drizzle,

on our o the ve nights with the largest mortality.

On the th occasion, however, the weather was clear.

Landscaping and Vegetation

GelbandDelacretaz(2006,2009)evaluateddatarom collision mortality at Manhattan building a-

cades. They ound that sites where glass refected

extensive vegetation were associated with more col-

lisions than glass refecting little or no vegetation. O

the ten buildings responsible or the most collisions,

our were low-rise. Klem (2009) measured variables

in the space immediately associated with building

acades in Manhattan, as risk actors or collisions.Fog increases the danger o light both by causing birds to fy lower and byreracting light so it is visible over a larger area. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

Lower foor windows are thought to be more dangerous to birds because they

are more likely to refect vegetation. Photo: Christine Sheppard, ABC

-

7/30/2019 Bird Friendly Building Design

41/58

41Bird-Friendly Building Design

Both increased height o trees and increased height

o vegetation increased the risk o collisions in all.

Ten percent increases in tree height and the height

o vegetation corresponded to 30% and 13% in-

creases in collisions in all. In spring, only tree height

had a signicant infuence, with a 10% increase

corresponding to a 22% increase in collisions. Con-

usingly, increasing acing area dened as the

distance to the nearest structure, corresponded

strongly with increased collisions in spring, and with

reduced collisions in all. Presumably, vegetation in-

creases risk both by attracting more birds to an area,

and by being refected in glass.

Research: Deterring CollisionsSystematic eorts to identiy signals that can be

used to make glass visible to birds began with the

work o Klem in 1989. Testing glass panes in the

eld and using a dichotomous choice protocol in

an aviary, Klem (1990) demonstrated that popular

devices like diving alcon silhouettes were only

eective i they were applied densely, spaced two

to our inches apart. Owl decoys, blinking holidaylights, and pictures o vertebrate eyes were among

items ound to be ineective. Grid and stripe pat-

terns made rom white material, one inch wide were

tested at dierent spacing intervals. Only three were

eective: a 3x4 inch grid, vertical stripes spaced our

inches apart, and horizontal stripes spaced about an

inch apart across the entire surace.

In urther testing using the same protocols, Klem

(2009) conrmed the eectiveness o 3MTMScotch-

calTM Perorated Window Graphic Film (also known as

CollidEscape), WindowAlert decals, i spaced at the

two- to our-inch rule, as above, and externally ap-

plied ceramic dots or rits, (0.1 inch dots spaced 0.1

inches apart). Window lms applied to the outside